Zamyatin’s We: A Collection Of Critical Essays 0882338048, 9780882338040

1,476 238 8MB

English Pages 0 [308] Year 1988

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents......Page 6

Acknowledgments......Page 8

Introduction. The Ultimate Anti-Utopia......Page 10

I. The Soviet View......Page 24

1. Alexander Voronsky: Evgeny Zamyatin......Page 26

2. Viktor Shklovsky: Evgeny Zamyatin’s Ceiling......Page 50

3. M. M. Kuznetsov: Evgeny Zamyatin......Page 52

4. O. N. Mikhailov: Zamyatin......Page 57

II. Mythic Criticism......Page 60

5. Richard A. Gregg: Two Adams and Eve in the Crystal Palace: Dostoevsky, the Bible, and We......Page 62

6. Christopher Collins: Zamyatin’s We as Myth......Page 71

7. Owen Ulph: I-330: Reconsiderations on the Sex of Satan......Page 81

III. Aesthetics......Page 94

8. Carl R. Proffer: Notes on the Imagery in Zamyatin’s We......Page 96

9. Ray Parrott: The Eye in We......Page 107

10. Gary Kern: Zamyatin’s Stylization......Page 119

11. Milton Ehre: Zamyatin’s Aesthetics......Page 131

12. Susan Layton: Zamyatin and Literary Modernism......Page 141

13. Leighton Brett Cooke: Ancient and Modern Mathematics in Zamyatin's We......Page 150

IV. Influences and Comparisons......Page 170

14. Elizabeth Stenbock-Fermor: A Neglected Source of Zamyatin’s We......Page 172

Addendum: “The New Utopia” by Jerome K. Jerome......Page 174

15. Kathleen Lewis & Harry Weber: Zamyatin’s We, the Proletarian Poets and Bogdanov’s Red Star......Page 187

16. E. J. Brown: Brave New World, 1984 & We: An Essay on Anti-Utopia......Page 210

17. John J. White: Mathematical Imagery in Musil’s Young Törless and Zamyatin's We......Page 229

18. Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr.: Zamyatin and the Strugatskys: The Representation of Freedom in We and The Snail on the Slope......Page 237

New Zamyatin Materials......Page 262

1. The Presentists (1918)......Page 264

2. Four Letters to Lev Lunts (1923-24)......Page 267

3. A Letter from Ilya Ehrenburg (1926)......Page 273

4. Excerpts from Unpublished Letters to his Wife (1929-30)......Page 274

5. The Modern Russian Theater (1931)......Page 278

6. The Future of the Theater (1931)......Page 291

7. Auto-Interview (1932)......Page 296

Sources......Page 302

Bibliography for Further Reading......Page 306

Citation preview

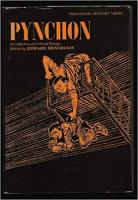

ZAMYATIN’S WE A Collection of Critical Essay Edited & Introduced by Gary Kern

Ardis, Ann Arbor

Gary Kern, Zamyatin's We Copyright © 1988 by Ardis Publishers All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Printed in the United States of America

Ardis Publishers 2901 Heatherway Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Zamiatin's We. Bibliography: p. 1. Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich, 1884-1937. My. 1. Kern, Gary. PG3476.Z34M938 1988 891.73’42 88-3502 ISBN 0-88233-804-8 (alk. paper)

Contents

Introduction

9

THE SOVIET VIEW

I.

23

1.

Alexander Voronsky: Evgeny Zamyatin

2.

Viktor Shklovsky: Evgeny Zamyatin’s Ceiling

3.

M. M. Kuznetsov: Evgeny Zamyatin

4.

O. N. Mikhailov: Zamyatin

II.

MYTHIC CRITICISM

25 49

51

56

59

5.

Richard A. Gregg: Two Adams and Eve in the Crystal Palace: Dostoevsky, the Bible, and We 61

6.

Christopher Collins: Zamyatin’s We as Myth

7.

Owen Ulph: I-330: Reconsiderations on the Sex of Satan

III.

AESTHETICS

70 80

93

8.

Carl R. Proffer: Notes on the Imagery in Zamyatin’s We

9.

Ray Parrott: The Eye in We

106

10.

Gary Kern: Zamyatin’s Stylization

11.

Milton Ehre: Zamyatin’s Aesthetics

12.

Susan Layton: Zamyatin and Literary Modernism

118

130 140

95

13.

Leighton Brett Cooke: Ancient and Modern Mathematics in Zamyatin's We 149

IV.

INFLUENCES AND COMPARISONS

14.

Elizabeth Stenbock-Fermor: A Neglected Source of Zamyatin’s We 171 Addendum: “The New Utopia” by Jerome K. Jerome 173

15.

Kathleen Lewis & Harry Weber: Zamyatin’s We, the Proletarian Poets and Bogdanov’s Red Star 186

16.

E. J. Brown: Brave New World, 1984 & We: An Essay on Anti-Utopia 209

17.

John J. White: Mathematical Imagery in Musil’s Young Törless and Zamyatin's We 228

18.

Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr.: Zamyatin and the Strugatskys: The Representation of Freedom in We and The Snail on the Slope 236

New Zamyatin Materials:

169

261

263

1.

The Presentists (1918)

2.

Four Letters to Lev Lunts (1923-24)

266

3.

A Letter from Ilya Ehrenburg (1926)

272

4.

Excerpts from Unpublished Letters to his Wife (1929-30)

5.

The Modern Russian Theater (1931)

6.

The Future of the Theater (1931)

7.

Auto-Interview (1932)

Sources

295

301

Bibliography for Further Reading

305

277

290

273

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publications for permission to reprint copyright material: Slavic Review: Richard A. Gregg, “Two Adams and Eve in the Crystal Palace: Dostoevsky, the Bible, and We” (No. 4, 1965).

Slavic and East European Journal: Carl R. Proffer, “Notes on the Imag ery in Zamjatin's We” (No. 3, 1963); Milton Ehre, “Zamjatin’s Aesthetics” (No. 3, 1975); Susan Layton, "Zamjatin and Literary Modernism” (No. 3, 1973); Christopher Collins, “Zamjatin’s We as Myth” (No. 2, 1966). Comparative Literature: John J. White, “Mathematical Imagery in Musil’s Young Törless and Zamyatin’s We” XVIII (1966). Russian Review: Elizabeth Stenbock-Fermor, “A Neglected Source of Zamiatin’s Novel ‘We’” (No. 2, 1973). Other published essays and materials first appeared in Russian Literature Triquarterly, published by Ardis. All sources are listed at the back of the book.

INTRODUCTION THE ULTIMATE ANTI-UTOPIA

Nearly seven decades since it was written, the novel We (Russian title, My) remains an exciting and influential work of science fiction, political satire and experimental prose. Its basic plot, whereby a true believer comes to question the validity of a totalitarian state and thus to transform it from a utopia into an anti-utopia, has been repeated by Aldous Huxley (coincidentally) in Brave New World (1932), George Orwell (consciously) in Nineteen Eighty Four (1948) and dozens of writers and film-makers (unknowingly) in the fifties, sixties and seventies; yet its artistry, prophetic power and underlying philosophy remain unsurpassed. Although it makes a statement against the perma nence of any human achievement, We has established itself as the most significant anti-utopian novel of the century. Zamyatin finished the novel in 1920 and sent it the next year to the Grzhebin House in Berlin, which published books simultaneously in Germany and Russia. In Petrograd (later Leningrad), the work became known to fellow writers by means of author’s readings, such as the one Zamyatin gave the Union of Writers in 1924. Publication was announced, but never realized in Russia: the book has the distinction of being the first novel banned by the Glavlit (Chief Administration for Literary Affairs), established in 1922. As this censorship board was understood at that time to be a prophylactic rather than corrective device—to block publication of pornography and works of an overtly counterrevolutionary nature, there can be no doubt about the reception of We by Soviet officialdom. It was little short of treason. For this reason the first publication was in English, in a translation by Gregory Zilboorg in 1924. Three years later, when the book was considered for transla tion into Czech, Marc Slonim, then the editor of Volia Rossii, a Russian emigre journal in Prague, obtained the original and published it, palm ing it off as a translation into Russian from Czech. (He tried to mask the original by changing some words.) This foreign publication provided the basis for attacks on Zamyatin at home as an anti-Soviet writer. He was vilified in the press, and his books and plays were banned. Zamyatin answered the charges point for point with customary 9

10

Introduction

frankness and irony in a letter to the Union of Writers, and resigned from the chairmanship of the Leningrad branch. But he had to recog nize that the “death sentence” for a writer—not to be able to write—had been passed upon him. The systematic newspaper campaigns and the ban on publication made continued creative activity in Russia unthinkable. He therefore took the bold step of writing directly to Stalin, as did Mikhail Bulgakov at about the same time. Acknowledging his “very inconvenient habit of saying not what is expedient at a given moment, but what strikes me as the truth,” Zamyatin asked to be de ported from the country. With Maxim Gorky’s intercession, Zamyatin and his wife were permitted to emigrate to Paris. Once abroad, he shunned emigre circles, wrote interesting articles on the theater and a few film scenarios (including one of We), and, like so many emigres, hoped to return to his homeland. Zamyatin died in March, 1937. His death went unmentioned in the Soviet press, and his funeral was attended by only a few friends.

Texts

The original Russian manuscript of We has not come to light. In 1952 the Chekhov Publishing House of New York City brought out a Russian-language edition, presumably based on the text sent to New York in 1921 (by Zamyatin?) for an English translation. But if so, altera tions of type styles, spellings and so on may still have been made. Since the Czech publication was intentionally defaced, and in any event is not readily available, the Chekhov edition has become the standard, if not canonical, source for the original. (The 1967 Inter-Library Literary Associates publication is simply a photocopy of the Chekhov edition.) Possibly the author’s manuscript lies in a Soviet archive or in the estate of Ludmilla Zamyatin awaiting the attention of a lucky textologist. As of this writing, four English translations have appeared. The first, the aforementioned effort of Zilboorg, was brought out by Dutton in 1924 and reprinted in 1952 with various covers. Dr. Zilboorg was an interesting man who also translated Paracelsus from Old German; his version of Zamyatin is accurate and retains some of the spirit of the twenties, but today seems old-fashioned and lifeless. The translation by Bernard Guilbert Guerney, included in An Anthology of Russian Litera ture in the Soviet Period from Gorki to Pasternak (Vintage, 1960) and republished separately (London: Jonathan Cape, 1970), has much more zip; it finds imaginative equivalents, invents words, uses different print styles and even tosses in footnotes from a “Venusian

Introduction

11

investigator.” It best captures the hectic, mind-boggling pace of the original, but is not very reliable for the purpose of literary analysis. This distinction goes to the third translation, that by Mirra Ginsburg (Bantam, 1972), which steers a middle road between the stiffness of Zilboorg and the excesses of Guerney. It is the most reliable for classroom use. A new, fourth translation by S. D. Cioran was just published by Ardis in Russian Literature of the 1920s (1987).

Plot It is assumed that purchasers of the present book will be familiar with the contents of We, but perhaps a plot synopsis will prove a useful reminder. The chief characters are the following: D503—engineer, builder of the spaceship Integral. I-330—a leader of the revolutionary movement Mephi. 0-90—a sexual partner of D-503. U—the controller at D-503’s apartment building. R-13—a poet, D-503's friend. S-4711—a Guardian interested in D-503. Scissor-lips—a physician and co-conspirator with I-330. The Benefactor—Head of the One State.

The action takes place in the thirtieth century, a thousand years after the world has been subjugated to the rule of the single state and human life in all its particulars has come to be regulated by scientific reason. This reason is manifested in the omnipotence of "The One State,” guided by the omniscience of the one man, the "Benefactor.” One of the instruments of control, the “Table of Hourly Commandments,” schedules the daily activities of waking, working, eating, defecation, sleep, and is understood as the mathematical guarantee of happiness. For a person to be happy, it is reasoned, "the denominator in the fraction of happiness. . . [must be] reduced to zero,” that is, freedom must be eliminated. Freedom is seen as the slow murder of a society, mathematically much worse than the physical murder of one man. With freedom standing at zero, there is no inequality, no reason for envy, and the nominator—namely, whatever the state permits—becomes infinite by comparison. Thus the rule of the One State obtains divine force. So that this happiness not be threatened by freedom, all houses are made of glass. This facilitates the work of the “Bureau of Guardians,” special agents who watch the citizens to ensure their unin-

12

Introduction

terrupted tranquility. All work is performed as a group activity, and all group activities are regimented to ensure unanimity of thought and action. The organization “splits into separate cells” only twice a day, when citizens may stay alone at home. The Table of Hourly Command ments allows for this by scheduling sexual activity on certain days at this time. Each male citizen, designated by a consonant and odd num ber at birth instead of by a name, may draw a ticket for any available vowel and even number, i.e., female citizen, for use at this time. Only on “Sexual Days,” during the “Personal Hours,” may shades be drawn in the glass houses. Parenthood, as well as love, obtains a mathematical basis with the “Maternal and Paternal Norms.” The Personal Hours, however, are felt to be a flaw in the equation of happiness, conducive to anxiety, and at the beginning of the account it is hoped that eventually every second of every citizen’s existence will be planned by the One State. The thoughts of the numbers are protected by the one newspaper, “The State Gazette,” and “The Institute of the State Poets and Writers,” both of which glorify the One State and the Benefactor. The One State itself, situated in an undefined area of the globe, is protected from the vicissitudes of weather by a glass dome and a glass wall, beyond which nature still exists in a savage state. The story is told by the diary of D-503. His first entry explains that he is the chief engineer in the construction of a spaceship designed to carry the message of reason to other worlds. His diary is in fact part of the cargo. Addressing his unknown readers, D-503 compares the life in the One State with that of ancient times (i.e., our own). He demons trates the superior quality of the Table of Hourly Commandments over the apex of ancient literature, “The Time Table of All the Railroads,” and marvels that people once lived chaotically, without obligatory walks, without predetermined sexual hours. “Like beasts, they bore offspring blindly. Isn’t it ludicrous—to know horticulture, poultry culture, pisciculture . . . and yet to be unable to reach the last rung of this logical ladder: pediculture. To be unable to think out the logical conclusions: our Maternal and Paternal Norms.” Explaining the origin of the One State, D-503 tells of a two-hundred year war and the development of a new naphtha food which eradicated 99.8% of the world population: “But then, cleansed of its millennial filth, how shining the face of the earth became." D-503’s satisfaction with the One State is challenged by the appearance of I-330, a disturbing woman with disturbing ideas. Her black clothing of a former time, her smoking, her preference for the music of ancient composers over that produced by the state

Introduction

13

music-making boxes, and especially her sarcastic manner excite un familiar sensations in the mathematician. He becomes reflective, ex periences the ancient disorder of dreams, commits the crime of not sleeping and even wonders if his knowledge is only faith. At first he is reassured by the warm breath of the Guardian Angel on the back of his neck, but day by day he falls deeper into doubt. Even his mathematical certainty—“Eternally in love are two times two, forever combined in a passionate four”—is upset by the notion of irrational numbers, suggest ing an unknown chasm into which he is falling. At last he understands that he is in love with I-330 and is afflicted with the disease of having a soul. After an unprecedented demonstration of opposition at the "Day of Unanimity” (the traditional re-election of the Benefactor), I-330 takes D-503 beyond the Green Wall, where he sees primitive people and learns of the revolutionary movement. This sets the stage for the main philosophical statement of the novel: “There can't be a revolution ... our revolution ... was the last." “My dear, you’re a mathematician ... Name the last number for me." "... That's absurd. Since the number of numbers is infinite, why would you want the last?" "Well, and why would you want the last revolution? There is no last, revolutions are infinite."

The revolutionary attempt to seize the spaceship fails, but D-503 is not implicated. As the epidemic of the soul spreads, the Medical Bureau perfects a device to remove the faculty of imagination—the last obsta cle to complete happiness. The operation becomes mandatory for all numbers under penalty of liquidation by the “Machine of the Benefactor.” After painful hesitation, D-503 submits to the “fantasiectomy” and betrays his former lover. I-330 is tortured and sentenced to the Machine. D-503, returned to the fold, regrets the revolution and ends as he began: “And I hope—we will conquer. More: I am certain—we shall conquer. For reason should conquer.” Within this plot, there are numerous subplots and subtleties. For example, one can follow the spread of the soul “epidemic” to other characters in contact with the love-smitten D-503: 0-90 falls in love with him, becomes jealous of I-330 and illegally conceives a child by him; U secretly reads his diary, falls in love with him and informs on the other revolutionaries, thus affecting the outcome of the story. One can ex plore the contrast between illusion and reality—D-503’s initial under standing of the state and the revolutionary movement, and his ultimate realization that he has been used by both. One can trace at least three

14

Introduction

levels of time in the diary: 1) the present tense—the story as it unfolds, 2) the future tense—the world lying one thousand years ahead, 3) the past tense—the story of conversion and brainwashing completed, the diary sent back through time from the 30th century to our own 20th century.

Interpretations

One of the marks of a great book is its susceptibility to many levels of interpretation, all apparently valid and convincing. We is such a book. It has been analyzed by American Slavists perhaps more than any other modern Russian novel; it has been picked to pieces by different, sometimes antithetical methods; yet it always holds up. Its appeal is not limited to Russian studies: We is commonly assigned in courses of political science, history, science fiction, utopian literature, and so on. In the classroom, it can be depended upon to excite students as few other books. First contact with We is invariably thrilling: the reader feels chal lenged and compelled to make his own analysis, often repeating observations printed in scholarly journals unknown to him. For this reason professors habitually photocopy one or two articles on We for their students. Such articles serve to refine the initial analy ses and to stimulate further discussion. This long-standing practice has inspired the present collection, which brings together the best of the old articles, some of the more exciting recent articles and a few other things as well. The intention is to provide a handy sourcebook for interpreta tions of Zamyatin—for professors, students and readers in the general public who explore on their own. The Soviet treatment of We is unfortunate, but instructive. Since the novel was banned in 1922, later critics were reluctant to show any familiarity with the original text. Instead, they relied on an essay written by Alexander Voronsky, editor of the first state-sponsored cultural-literary journal, Red Virgin Soil, and published in Moscow in 1922. Voronsky is generally regarded as a “moderate” Marxist critic of the twenties, but even so it is clear from the essay that with him ideolo gy came first and literary analysis second. In the essay, he delivers a bitter denunciation of Zamyatin’s life and work, but also cites long por tions of the novel. The historical respectability of Red Virgin Soil and Voronsky’s negative assessment of Zamyatin made this essay the ideal source for subsequent critics. They, in effect, implied that it was proper for Voronsky to read and interpret the work in his time, but no one afterwards should dare touch the poisonous thing. While seconding

Introduction

15

Voronsky, they avoided mention of the fact that he had been sent to Siberia and perished in the purges. He was, however, posthumously rehabilitated, and to stress the importance of his essay, the Soviet publishing houses began to reprint it in 1963. It has not yet been sup planted by anything new during glasnost. The complete essay is in cluded here in an accurate English translation. Also included from the Soviet side are a sort of off-beat piece by Viktor Shklovsky, actually a critic very close to Zamyatin, but at that time in the process of making amends with the Soviet government, and two accounts from the sixties, interesting for their slight departures from Voronsky. Notes at the back of the book spell out these particulars. On the Western side, no single approach is dominant. Rather, as already suggested, a profusion of interests and methods prevails. Re lying on what seem to me the chief aims, I have collected articles into three categories, admittedly rather loose. The first, “Mythic criticism,” embraces the concerns of myth, religion and psychology. The second, “aesthetics,” focuses on analysis of themes, structures and devices. The last, “influence and comparisons,” explores influence on Zamyatin, coincidental expressions in other writers and Zamyatin’s influence on others. The essays are included in their entirety, which produces much overlapping, but also permits one to dip into the volume wherever he chooses and to read the articles in whatever order serves best. Zamyatin was not known to have made any special study of psychology, though he could not have failed to observe the European fascination with Freud during his stays in Germany and England. It seems fairly certain that he was unfamiliar with Jung’s works, which were not yet famous in Europe and virtually unknown in Russia. Nevertheless, We is as much a model of Jungian psychology as Her mann Hesse’s Steppenwolf, written in 1927 under the direct influence of Jung. This can be explained only by the fact that Zamyatin drew on the same psychic forces that Jung described. In Jungian terms, the hero of We is immediately recognizable as the persona—that aspect of the psyche which conforms to society, adheres to conventions, follows reason, presents a good face. I-330 appears as his anima, the hidden female side of this blocked personality, the source of spontaneity, irrationality, passions, dreams, love. It is she who awakens the unconscious. Thus aroused, D-503 discovers a wild, violent self, an impetuous, hairy-handed beast—his shadow. This process of awakening, which all men must confront or avoid, is what Jung called individuation, the discovery and conscious integration of the self within—the discovery of one’s soul. With Jung the proper outcome of this process is a self-sufficient and creative personality, but in the novel

16

Introduction

it is subverted by D-503’s fantasiectomy—with a definite artistic impact. The first critic to take up this line of interpretation is Christopher Collins, whose article “Zamyatin’s We as Myth” is included here. Both Jung and Zamyatin turn naturally to myth for the story of conscious awakening—Adam and Eve. D-503 assumes the role of Adam, I-330—Eve; she seduces him and takes him beyond the wall surrounding a paradise of unconscious happiness. The article which first examined the Adam-Eve premises of We—regarded as a classic by Zamyatin scholars—is Richard A. Gregg’s “Two Adams and Eve in the Crystal Palace: Dostoevsky, the Bible and We.” Its decoding of the characters’ names (or rather, designations) gives proof of the author’s and the critic’s devilish cleverness. A more recent look at the psycholo gical underpinnings of We, Owen Ulph's “I-330: Reconsiderations on the Sex of Satan,” drops the expected tone of scholarly respectability and plunges lustily into the heart of delicious sado-masochism. As with Nabokov, Zamyatin has the fire to ignite not only the critic’s literary interest, but his whole mind. Slavic studies in the sixties were largely concerned with the twen ties of Russian literature: this was still pretty much virgin territory, barely touched by translators and critics. While the classics of the nineteenth century were world famous and well worked by the previous generation of scholars, graduate students in the sixties, by turning to the early post-revolutionary literature of Russia, could discover exciting works and authors totally unknown to the general public. (At the same time in the Soviet Union a period of relaxed controls produced the "discovery” and publications of Bulgakov, Platonov, Zoshchenko, Mandelstam, etc.) One result of this development was the founding of Ardis, an American publishing enterprise devoted to Russian literature, which set off a veritable explosion of translations, articles and even first publica tions of original texts forty years old. Another was the phenomenal impact of Russian Formalism on students at this time. Nearly everyone was infected by it, and its influence endures to the present day. Reasons both intrinsic and extrinsic account for this. For the first, For malism offers a ready tool for literary analysis; the young scholar does not require the forbidding and sometimes fuzzy erudition of his profes sors in order to discuss the works he admires. With care and practice, he can pick a work apart and examine its components with precision and authority. For the second, the method fills up space and time; it enables the student to write his paper almost automatically, and the novice professor to explicate his text through the full hour. Its virtue lies in its avoidance of pompous statements of philosophy, religion or politics; its vice lies in relegating these concerns to the unspeakable,

Introduction

17

often categorizing the most heartfelt passages of a literary work as “padding,” “suspenseful retardation of plot” or “insertion of social material.” In short, Formalism in the sixties and beyond contains the same virtues and vices as it did in the twenties. Most of the articles gathered here under the rubric "Aesthetics” are touched to a greater or lesser degree by the Formalist persuasion. Their chief concern is the structural make-up of We. Accordingly, the early “Notes on the Imagery of We” by Carl Proffer looks at the color yellow through the novel. Ray Parrott looks at the eye as a basic image; he counts 160 instances of its usage. I attempt to break Zamyatin’s style down into language, imagery and theme. Milton Ehre takes on the task of describing Zamyatin’s aesthetic system. Susan Layton seeks out the elements of Zamyatin’s “Neorealism.” Leighton Brett Cooke makes a thorough investigation of the mathematical images and argu ments of the novel. All these individual approaches demonstrate that We achieved a complexity whereby the reader can take one perspec tive as his point of departure and profitably carry it through the whole work. As the Formalists were fond of saying, the "thing” became “organic.” Zamyatin was very well-read in Russian and foreign literature, par ticularly English. As the most talented essayist of post-revolutionary Russia, he naturally wrote about his reading, again providing material for the study of his novel. On the Russian side, critics usually name Gogol, Leskov, Dostoevsky (Notes from Underground, The Grand Inquisitor), Remizov, Belyi (Petersburg), Bogdanov (Red Star) as influences. Zamyatin’s own “English works” should not be neglected: The Islanders (a novel), Fisher of Men (a story), The Society of Honor able Bell Ringers (a play)—these lampooned English stuffiness and sanctimony. Of foreign writers, Zamyatin admired Anatole France, Jack London, O. Henry and most of all H.G. Wells (The Time Machine, When the Sleeper Awakes); he wrote superb essays on each of these men. Zamyatin was an outstanding figure in post-revolutionary Russia who by his lectures, literary studies and creative works influenced a whole generation of writers, in particular, the Serapion Brothers, Boris Pilnyak, Andrei Sobol, Yury Olesha. Despite the long interdiction against his works, his influence can be felt in the reawakened Russian fantasy of the sixties, particularly Abram Tertz (Andrei Sinyavsky), Vladimir Voino vich and the Strugatsky brothers. His influence in the West is widespread, but most often indirect—by way of Orwell. The articles in the last section of this collection look into the matter of influences and coincidences—such as the mathematical images in Musil’s novel Young Törless. They perform the useful service of proving

18

Introduction

Zamyatin’s kinship with other works by their wide and careful readings. While all credit Zamyatin with creating a seminal work of fiction, one or another of them takes a surprisingly critical approach to him. Contrary to Soviet aspersions, Western critics are not necessarily enamoured of Zamyatin’s philosophy and blinded by it to the quality of his artistic work. Certainly the most formidable assault on Zamyatin’s outlook is to be found not in Voronsky or later Soviet critics, who indulge in ideologic al invective, but in the essay by the dean of American Soviet Russian literary studies and longtime admirer of Zamyatin’s works: "Brave New World, 1984, and We: An Essay on Anti-Utopia” by Edward J. Brown. Contradicting almost all previous writing on Zamyatin, Brown asserts that the writer did not look to the future, but to the past. He consistently repudiated the city as a desirable place to live and found his preferred subjects in "the pre-civilized and the primitive." The hero and heroine of We try to escape the "conventions of their time” by running beyond the wall to primitive hairy creatures. Furthermore, Brown states, Zamyatin was not an original thinker: his thought is “a mixture of his basic roman ticism with modern scientific vocabulary and Hegelian dialectics,” the latter being picked up as part and parcel of his time. Brown regards Zamyatin’s philosophy as an "artificial intellectual superstructure" de signed to protect writers against the demand to take a definite ideolo gical position. Zamyatin’s merit lies not in his philosophy, but entirely in his art. In one way, this essay is consistent with Zamyatin’s thought: it is heretical and disruptive of previous thinking. But to my mind it is too literal. The flight beyond the Green Wall is not the goal: the point is to bring nature into the city. Besides, the flight is symbolic: not a return to the ape, but to the unconscious, which lives not only in the past, but also in the present, and points the way to the future. Zamyatin did not reject the city, but its pernicious aspects—its impersonal structures and dehumanizing routines. And he never advocated the simple country life or the ideal village commune—he ridiculed them. Finally, Zamyatin as a thinker did pick up from Hegel, as did Feuerbach, Marx, Kierkegaard, Bergson et al., but was not unoriginal for all that. Although he could hardly be expected to rework Hegel as thoroughly as the great philosophers, he did make a significant innovation in the dialectic, both in his fiction and exposition: he remained dialectical. Zamyatin took Marx at his word. If we must "contemplate every accomplished form in its movement, that is, as something transitory” (Marx), then a final solution to the problems of social structure, government, justice and happiness cannot be achieved. There will be no final synthesis in which all existence achieves self-consciousness

Introduction

19

and God contemplates Himself (Hegel), nor will a dictatorship of the proletariat eliminate class distinctions, cause the state to wither and Beget a final communist society (Marx).. Zamyatin had the courage after the revolution to remain a revolutionary, to deny utopian solutions,’ to regard established truths as transitory. All truths will pass: “Truth is a thought suffering from arteriosclerosis.” It is this simple, but fun damental innovation in dialectical thinking which immunized some wri ters against dogmatism in the twenties and which excites the minds of readers today. Also, paradoxically, it locates a single sure outlook in a whirlwind of change, just like the maxim of Heraclitus—“All flows,” which has yet to be refuted.

Ideology

Whatever one's interest in We, it is impossible to ignore its ideology. Zamyatin was arrested in 1905 for his involvement in the revolutionary movement. He was a Bolshevik at the time. After seven months' solitary confinement in a prison in Petersburg, he was exiled to his native town of Lebedyan, where the stillness began to weigh on him. Returned to Petersburg, he completed courses in the Polytechnic Insti tute and travelled through Russia building ships. At the same time he began to write stories, and by 1911 felt he had found himself. Two years later he and his publishers were arrested and tried in court for his story A God-Forsaken Hole (Na kulichkakh), a satire of garrison life in the sticks. In March 1916 he went to England to supervise the building of Russian ice-breakers. While bombs were falling from German zeppelins, Zamyatin was busy writing his satire of English conformity, The Islanders. News of the February Revolution in Russia changed all his plans, and he hastened to return home, finding passage on a rickety ship only by September 1917. Present for the October Revolution, Zamyatin elected to stay and work with the new government, simul taneously teaching courses in shipbuilding and prose writing. As an “expert,” he was active in numerous state-sponsored cultural enterprises, but was now a “Fellow-Traveller”—no longer a Bolshevik. In 1922, Zamyatin was arrested and placed in solitary confinement, again in the same prison and cell block as in 1905. Then he was exiled. Details about the incident are skimpy, but it seems highly likely that We played its part. Zamyatin returned to Petrograd-Leningrad and con tinued to work there until compelled to address his letter to Stalin. From this sketch of his career, it is clear that he took a critical view of whatev-

20

Introduction

er society he happened to be in. Pre-revolutionary Russia, wartime England, post-revolutionary Russia—each began to bore him. Zamyatin wrote his credo in the essay of 1918, “Are They Scythians?”: The lot of the true Scythian is the thorns of the vanquished. His faith is heresy. His destiny is the destiny of Ahasuerus. His work is not for the near, but for the distant future. And this work has at all times, under the laws of all the monarchies and republics, including the Soviet republic, been rewarded only with a lodging at gov ernment expense—prison. (Translated by Mirra Ginsburg in A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin, University of Chicago, 1970, p. 23.)

Ever alert to the first signs of monolithic thought, Zamyatin reacted quickly to the new mores and institutions of the first Marxist state in history. By reducing them to their essence and extending them ad absurdem, he not only subjected them to ridicule, but in a sense pre dicted the future. We accurately presages Stalin’s cult of personality (“the Benefactor”), Pravda’s monopoly on truth (“the State Gazette”), the travesty of one-party voting (“the Day of Unanimity”), the control of literature (“the State Union of Poets and Writers”) and the Iron Curtain (or Berlin Wall), beyond which one is not allowed to go ("the Green Wall”). Some of Zamyatin’s predictions did not come to pass in the Soviet Union, such as the “Sexual Hours”—the twenties were rife with free-love theories, but Stalin enforced state marriage and puritanical relations, at least officially. Readers can gauge how well “pediculture” has been realized by Soviet child-care centers and schools. Or how well “fantasiectomy” has been realized in Soviet psychoprisons, euphemized as “Special Psychiatric Hospitals.” Probably it is not these shots, damaging as they are, which prevent the publication of We in the USSR. Soviet critics could dismiss them as peculiarities of the time, or find parallels in American history—for example, the spread of cults from the Oneida Community to Jonestown. Indeed, some of Zamyatin’s predictions more accurately hit our society: for the State Music Plant and music-making machines, we have the inescapable Muzak or soft rock in store, elevator and telephone on-hold; and for Sexual Hours, we have computerized dating and per sonal listings in porno sheets. As for bugging devices, it’s a toss-up who’s ahead. So rather it must be the ideological argument, the denial of a final revolution and a final truth, which is intolerable to the Soviet power. Were We published in the USSR, it would hardly cause a mass revolution, but it might start a little revolution in the mind of each reader. Thus it acts as a litmus test. So long as it is banned, all talk of freedom

Introduction

21

of speech and thought in the USSR must be regarded as sham. If ever it is allowed, we might pay attention to such talk—and expect the publica tion of Trotsky, Freud, Jung, Kierkegaard, all non-Marxist philosophers, all novelists, all poets.

Little Details Zamyatin’s name may be transliterated in three ways: Evgeny Zamyatin, Evgenii Zamiatin, Evgenij Zamjatin. This book uses the first in the text of the essays, but may use the second in footnotes when referring to Russian-language publications. The third may also appear in footnotes when it is in the original title of a publication. The first name Yevgeny or Eugene may also appear in such instances. The first entry of D-503 (fourth sentence of the novel) declares that the One State was founded a thousand years previous. In the third entry (third sentence), D-503 addresses the reader who may have only reached the stage of civilization 900 years previous. Thus some critics remark that the novel is set in the 29th century, others—in the 30th century. There are also articles which refer to other centuries, not in cluded here. It seemed opportune on this occasion to collect a number of Zamyatin materials which have come to light in recent years, even though they may not always touch on the novel. As with the collected articles, it would be a shame for them to remain scattered.

G. K.

THE SOVIET VIEW

EVGENY ZAMYATIN1 Alexander Voronsky

The example of Zamyatin excellently confirms the truth that talent and intellect, however much a writer might be endowed with them, are insufficient if he has lost contact with his epoch, if his inner sensitivity has betrayed him, and in the midst of contemporaneity the artist or thinker feels as though he were a passenger on a ship, or a tourist, looking around with animosity and impatience. With the appearance of A Tale of the Provinces (Uezdnoe) in 1913 Zamyatin immediately took a place among the prominent masters of the word. A Tale of the Provinces portrays our pre-revolutionary tsarist provinces with their sleepy, comfortable, fertile, serious, thrifty, devout inhabitants. A Tale of the Provinces is well known to the reader both personally and through the peerless fictional models of the classics, beginning with Gogol and ending with Gorky. The fragrant geranium, the ficuses, the vicious watchdogs, the deadly nightshade, the shamelessness, the stinking coziness, and the crude psychology have been encountered time and again. Nevertheless, Zamyatin’s A Tale of the Provinces is read with the most vivid attention and interest. Zamyatin had already at that time become established as an exception al enthusiast for and master of the word. His language is fresh, original, and exact. It is partly folk skaz, stylized and modernized to be sure, and partly the simple colloquial provincial speech of the suburbs, the out lying districts, and the Rasteryaeva streets.2 In this fusion Zamyatin created something his own, something individual. The spontaneity and the epic quality of the narration are complicated by the ironic and satiric al mood of the author. His skaz is not without reflection, and only appears to come straightforward from the author: actually everything here is written with a “trap,” and contains a hidden mockery, smirk, and spite. This is why the epic quality of the skaz slips out and the work lives and emerges into the realm of the contemporary and the topical. The provinciality of the language is ennobled and well thought out. Above all it serves vividness, freshness, and picturesqueness, and enriches the

25

26

Alexander Voronsky

language with words which have not become familiar or trite. It is as though there were before you just-minted coins, and not worn, dull, and long-circulated ones. Great austerity and economy. Nothing is said rashly; everything is joined together; there are no gaps. From the point of view of form the tale is like a monolith. Zamyatin had not yet lost control of his enthusiasm for words, as he was to do in some of his later works. There is no overloading, superfluous affectation, wordplay, liter ary foppery, or sleight-of-hand. He reads easily and effortlessly, and this does not at all hinder one’s becoming absorbed in the contents. This is already a manifestation of the great ability of the artist to instill an image in the memory with one stroke, with one touch of the brush. Zamyatin did not give us any new characters, but something old and familiar is rendered in a new and original light. The peaceful exist ence of A Tale of the Provinces is embodied in the ripe and juicy figure of Anfim Baryba. Before the eyes of the readers Anfim grows up from a boy into a provincial village policeman. The road is long, difficult, and rich in misadventures. Anfim is quadrangular. “Not for nothing did the provincial lads call him a flat-iron. Heavy, iron jaws, a very wide quad rangular mouth, and a narrow forehead: just like a flat-iron, with its point turned up. And Baryba is all in all some sort of broad, unwieldly, lumber ing creature, composed of rigid right angles.” The strong body of a beast, the soul of a beast, and all concentrated on one thing: gorging himself—for Anfim’s jaws easily crush stones into sand. They throw him out of school; Baryba doesn’t go home, but settles in a cowshed, goes hungry, steals, and winds up on this occasion in the hands of the 250-pound merchant’s wife, Chebotarikha. She, however, feels pity for Baryba after seeing his beastlike body, and Baryba—not the Baryba from the cowshed, but Chebotarikha’s right hand—has “boots like a bottle, and a watch made of silvei,” and esteem from all—above all from Chebotarikha herself, devout and insatiable at night. Happiness is not long-lived, however. Chebotarikha drives Baryba out because of the maid-servant Polka. Again the hungry life. But Baryba is a “tough cookie.” The monk Evsei turns up. Baryba robs him, then is paid by the provincial lawyer Morgunov to give false evidence in court. The tail-end of the revolution of 1905 rolls into the god-forsaken little town. There is expropriation, carried out by youths who manage to hide, with the ex ception of one. And to the greater misfortune of the district police officer, the colonel who arrives to judge him is suffering from stomach trouble, and there is no way the police officer can please him—and furthermore he cannot find the malefactors. The same Baryba rescues him from misfortune. For 150 rubles he proves that the tailor Timokha—the true bosom friend of Baryba—is among the malefactors.

Evgeny Zamyatin

27

Baryba is sorry for his friend, but he endures and attains a provincial nirvana: they give him silver buttons and gold braid. The policeman salutes him, and they hang Timokha. “It’s great to be alive!” Anfim is a symbol of what is provincial: bestial, chewy, fat-snouted, greasy, gluttonous. In the provinces God is something edible. There people devote themselves to eating to the point of satiety, so that the jaws grind away luxuriously, so that they can sleep to the point of stupor, and can procreate children with sweaty and sticky bodies. Bary ba himself is fortuitous: he could be born or not. But A Tale of the Provinces pushes him out and moves him into the limelight. He is awkward, obtuse, almost an idiot, cunning as a beast. But Chebotarikha, the monk Evsei, the attorney Morgunov, the district police officer, the public prosecutor, and the colonel need him; therefore he attains the “heights” without effort and struggle. The others are also bestial. Anfim takes them into himself; he is made from them; he is their clot. This edible quality is accentuated and rendered by the author with exceptional force. A Tale of the Provinces is only in part a story of everyday life. It is more a satire—and not simply a satire, but a political satire, brightly painted and bold for the year 1913. In distinction from a number of authors who wrote about provincial matters, Zamyatin linked Russian Okurovism3 with the entire Tsarist mode of life and its political system, and herein lies his unquestionable merit. But, strange to say, Zamyatin’s talent here achieves only half its goal. Something great, something sincere, something all-illuminating, which the reader finds in Gogol, in the satires of Shchedrin, in Uspensky, in Gorky, and even in Chekhov, is missing. It is as if the tale, in spite of its purity of style and form, falls to pieces before the reader. It is masterfully narrated and delightfully done, but done just so it doesn’t touch the reader deeply or penetrate inside, even though Baryba, Chebotarikha, Morgunov, Evsei, Timokha, and the district police officer stand before our eyes. Zamyatin approached provincial matters from another side in a different tale—“Alatyr.” Gogol already noted the Manilovism of our provinces. People live so-so, it would seem; it is not a heavenly life, but man is so inclined that he must without fail dream about something which does not exist and, perhaps, never will exist. Manilov has every thing and still fantasizes. But if not everything is well with the Manilovs, and they are pressured, no matter by what, they fantasize all the more. Zamyatin tells about these peculiar dreamers in “Alatyr.” Alatyr is a town.

28

Alexander Voronsky Among those inhabitants—needless to say it was inherited from mushrooms—there came to exist a downright unrestrainable fecundity. They bap tized children wholesale, by the dozens. There remained only one street passing through: a decree came out forbidding travel along the others, in order that the babies crawling in abundance through the grass would not be crushed.

However, the paradise at one time passed away. The Turkish war was on, many people were killed, and the maidens of Alatyr remained without eligible young men. From here the dreams of Alatyr became reality. Glafira, the daughter of the district police officer, moans for eligible young men and awaits a love letter from a handsome stranger. The district police officer, after unsuccessful attempts to marry off Glafira, settles himself still more firmly in his study and invents things. His latest discoveries are the secret of baking loaves of bread not with yeast, but with pigeon dung, and how to prepare waterproof cloth from ordinary unbleached linen. The archpriest Father Peter converses with devils when drunk and when sober; his daughter Varvara also becomes possessed in the absence of eligible young men. Rodivon Rodivonych, the inspector, delights in reading Almanach de Gotha. And then there is Kostya Edytkin, who works at the post office. He has a secret notebook in which is written “The Works of Kons. Edytkin, that is, mine.” And verses: “In my breast there lies a dream, but dear Glafira disdains me.” At night he writes with excitement and great love. In a word, each one has his dreams. Further, a prince arrives in the capacity of postmaster. True, he has a nose with a hump and has no chin—he is an oriental prince, but a prince nevertheless. And here is what happens: Glafira, Varvara, and the maidens all go out of their minds. And the price also has a most noble dream: all should speak one great language, Esperanto, and then the brotherhood of peoples would be realized. The district police officer, the inspector, Glafira, Varvara, the maidens,and others all study with the prince. The dreams end lamentably. Glafira and Varvara arrange to fight it out; Kostya endures a most cruel failure with the composition “The Internal Feminine Dogma of Godliness,” and failure in love also; the prince suffers failure with his Esperanto; the district police officer suffers failure with his experiments; and so forth. Here also appear the provincial, the bestial, and the edible, but in addition to this there are phantasms, mirages, and dreams. The phan tasms are pitiful and distorted, and they lead into a blind alley, but all the same they are phantasms. And so the meager and tedious life of Alatyr flows on between zoology and absurd fantasizing. The dreaming of the inhabitants of Alatyr, however, is distinguished from Manilovism by means of its dramatism; regardless of its absurdity, it eats into and

Evgeny Zamyatin

29

mangles life, flying asunder as dust at the first contact with life. And perhaps that is why the inhabitants of thousands of Alatyrs do not believe in the feasibility of the great impulses of the human spirit: after all, they have before their eyes only these nonsensical, unnecessary dreams. In “Alatyr” the basic features of Zamyatin’s artistic talent are those which appear in A Tale of the Provinces. The tale is somewhat less vivid, but there is in it the same enthusiasm for the word, the same craftsmanship, the same oblique observation, the same smirk and iro nical smile, the same anecdotal quality (more, perhaps, in "Alatyr” than A Tale of the Provinces), the same sharpness, abruptness, and promin ence of device, the same careful selection of words and phrases, a great force of picturesqueness, unexpectedness of similies, the isola tion of one or two traits, and restraint. Bestiality is also treated in the story "The Womb” (Chrevo). Anifimya, a robust peasant woman, young, in the prime of life, kills her husband because of the need to have a child, and pickles his body. But here the force of the womb is presented in a different light. There is a great deal of lyricism in the story, and the bestial element in Anifimya is different from that seen in Baryba. One sympathizes with it. Bestiality splits in two: it is no longer in the image of Baryba, but in the image of Anifimya, touchingly thirsting for fertilization. The tale “At the World’s End” (Na kulichkakh) closely corresponds to A Tale of the Provinces and “Alatyr” in content and theme. Written at the beginning of the Russo-German War, it was confiscated by the Tsarist government and the author, as a Bolshevik, was imprisoned for antimilitaristic propaganda. (The tale appeared in print in issue number one of The Circle, the almanac of the writers’ artel.) A military unit is dispatched to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, to a sentry post forgotten by all and not needed by anyone. The oppressed, muddle-headed Russian peasants, very sharp-witted in economic and agricultural matters, but utterly obtuse with regard to service, adapt according to their needs as "gentlemen officers.” Their needs are highly peculiar: they teach one to speak French, another is transformed into the wet nurse and nanny of nine children, a third exists in the kitchen for the purpose of absorbing slaps in the face from generals—and all are reduced to the point where they lose their human traits, and it is not for nothing that the soldier Arzhanoy kills a Chinaman while out walking—in such a situation this is very natural. The author’s attention, however, is concentrated not on the Arzhanoys, but on a small group of officers. Kuprin’s The Duel (Poedinok) pales before the picture of moral decay and degradation depicted by Zamyatin: a cesspool in an

30

Alexander Voronsky

out-of-the-way place. There is the General—an exceptional glutton, a coward, a philanderer, a voluptuary, and a rotter; the narrow-minded pedant Shmit—fidgety, in his own way just, being changed into a miser able sadist; and Captain Nechesa, rearing nine children who in reality are not his; the weak-willed mellow Russian intellectual in an officer’s coat, Andrei Ivanovich; the lanky, absurd Tikhmen, vainly trying to solve the riddle of whether “Petyashka,” born to Nechesa’s wife, is his child or not; the quiet, half-crazy General’s wife; and the regimental lady, Nechesa’s wife—all chubby, and whose children are a living chronology. As in both A Tale of the Provinces and “Alatyr” it is deadly wearisome, sleepy, and absurd at the world’s end. But not so much wearisome as terrifying. In the tale this terrifying quality is particularly emphasized by the author, and the principal part of attention is concen trated on it—in distinction from A Tale of the Provinces and “Alatyr.” A terrifying quality exists in these works too, but there is more about bestiality and about a provincial fantasizing in them; here it is the basic thing. Beneath the cover of a tedious, petty life Zamyatin saw this terrifying quality and pointed out to his readers not that imperceptible, grey, slowly-enveloping side of it, which Chekhov wrote about in his time, but the genuinely bloody, hideously brutal, tragic side of it. True, at the world’s end, at the back of the beyond, they often fail to notice this side of it, but that is because it has entered into their everyday life. Tikhmen and the rectangular Shmit end their lives by suicide, Andrei Ivanovich becomes “ours," the soldiers are reduced to a bestial state, and the general basely, lispingly, and slobberingly rapes the tender and frail Marusia. “At the World’s End,” like A Tale of the Provinces, is a political and artistic satire. It makes much of what happened after 1914 understandable. In its own way it is a perhaps justified prophecy, but it also brings out, more so than the works written earlier, still another feature of Zamyatin’s artistic gift. The tale is cast in a genuine, lofty, and touching lyricism. Zamyatin’s lyricism has something all its own. It is womanly. In its details and subtleness it is always a kind of autumnal spider’s web—a Virgin’s thread. Here are Marusia’s words: “About one, very last little second of life—delicate as a spider web. The very last—it will break now, and everything will be silent...” Or, a slight hint “about the bird dozing on the snowy tree, the blue wind.” This is the way it is everywhere in Zamyatin’s later work. One can speak of this lyricism in the author’s words: not meaningful, not anything special, but it is re tained in the memory. Perhaps it is because of this that Zamyatin’s female types succeed so well, so intimately, and so tenderly: they all have a special something, they are not like one another—and in the best, the favorite of them there throbs that small, sunny, dear, memor-

Evgeny Zamyatin

31

able something which is scarcely perceptible to the ear, but which is sensed by the entire being. And still, when you read “At the World’s End,” every now and then old acquaintances are called to mind: Kuprin’s The Duel, Sergeev-Tsensky’s “Lieutenant Babaev” and "Kukushka,” Gogol’s Petukh, and so forth. Let us note, however, that in all these things, in A Tale of the Provinces and in “At the World’s End,” the struggle against stagnation, obtuseness, and staleness reflects only a personal attitude. Timokha, Marusia, and Andrei Ivanovich are isolated rebels, not united with any collective or group. This is not accidental—but greater detail about that below.

II After a two-year stay in England during the war years, Zamyatin brought back “The Islanders" (Ostrovitiane) and “A Fisher of Men" (Lovets chelovekov). From A Tale of the Provinces to London and Jesmond. From dirt, pigs, and mire to stones, concrete, iron, steel, zeppelins, and underground roads. From Chebotarikha, Baryba, and district police officers to the sedate English life, mechanized and sche duled in detail. For Vicar Dooley, author of a book called The Testament of Compulsory Salvation, everything is done according to hours: ... a schedule for the hours of food intake; a schedule for the days of repentance (twice a week); a schedule for the enjoying of fresh air; a schedule for the pursuit of charity; and, finally, among a number of others—one schedule, out of modesty untitled and especially concerning Mrs. Dooley, on which the Saturdays of every third week were marked.

Life is a machine, a mechanism, and everything is thoroughly regulated; all the people are identical, with identical walking sticks, top hats, and dentures. In “The Islanders" and “A Fisher of Men” there is satire on English bourgeois life—biting, sharp, effective, finished down to the details and to the point of scrupulousness. But the more carefully one reads both the long tale and the short story, the more strongly one gets the im pression that neither the heart nor the bosom of life has been captured, but rather, that its surface has been captured. In essence the artist has produced a filigree work on slight material. Here are the trifles of British life; it is true that these trifles drive one to distraction, but this does not

32

Alexander Voronsky

change matters. A life mechanized according to a timetable; the gleam ing pince-nez of Mrs. Dooley; the gentlemen with dentures; Campbell's mother, Lady Campbell—a “frame in an old umbrella, broken by the wind”—with her sedateness and her lips wriggling like worms; the ser mons about compulsory salvation; visits to cathedrals; the Pharisaism; the espionage; the English crowd demanding execution; and the execution—excellent, well done, clever, talented—but very similar to the tales (told by the Andrei Ivanoviches who have been abroad) of the Philistine mores of virtuous Swiss landladies, who are horrified at the sight of men’s galoshes, forgotten overnight by the room of a female Russian emigree. They are engaging and interesting tales, and it could happen that some Andrei Ivanovich or other winds up in prison because of these galoshes; there he may do some other unseemly thing, for which he will be hanged or executed in the electric chair. To present similar cases in the form of conclusive artistic generalizations is not enough in our days, after the war and during the mightiest of social cataclysms. In England, as everywhere, there is not one, but rather, there are two nations, two peoples, two races; and he who does not understand this, and he who, in our time, through the eyes of one nation, cannot look at the other nation even for a minute and weigh and evaluate it, will never feel the true depths of social life, its most profound contradictions, and its “essence.” And Zamyatin looks through the eyes of the attorney O’Kelly, the coquette Didi, and Campbell; there is no mention of these other eyes without which one can no longer make a step. O’Kelly and Didi are the “underminers of the foundations” of loyal English life. The bases are “shaken” in the living room of the venerable vicar, at dinner at Lady Campbell’s (O’Kelly appears for dinner in a morning coat, prefers whiskey to liqueur, and embarks on a conversa tion about Oscar Wilde), in Didi’s room, in the circus, and elsewhere. It is precisely in this way that a Russian “shakes” principles in the antechamber of a Zurich landlady by absent-mindedly leaving his galoshes. It seems that other eyes of the other nation in England would have noticed, from the shipyards and the coal mines, something a bit more serious and more substantial, and would have arrived at conclu sions in a more substantial manner. It is possible to object that the author uses a special artistic device here: an immensity of trifles, with a bloody denouement, seemingly underscores the unbearable asphyxia of the situation in which the abor igines of London and Jesmond find themselves. However, this is more than an artistic device here; it is something more profound and intimate, connected by strong and indissoluble roots with Zamyatin’s artistic credo. According to the author’s ideology there are two forces in the

Evgeny Zamyatin

33

world—one striving for peace, the other eternally rebelling and dynamic. In his latest unprinted and fantastic novel We, one of the heroines says: “There are two forces in the world, entropy and energy. One leads to blessed peace, to happy equilibrium; the other leads to the destruction of equilibrium, to agonizingly perpetual motion.” A Tale of the Provinces, “Alatyr,” and “At the World’s End” represent equilibrium and entropy. But here too another, opposite, force is at work, albeit in distorted form. It is seen in Timoshka, in the absurd phantasms of Kostya and the other inhabitants of Alatyr, and in Marusia. In the short story “The Good-for-Nothing” (Neputevyi), the eternal student is a thoughtless and negligent sot who squanders his energies, and whose merry and impudent life ends on the barricades. In the short story “The Diehards” (Kriazhi), this force makes Ivan and Maria go against one another for a long time. They are obstinate, and such persons have to have this tight, resilient, willful, good-for-nothing quality. All the works published by Zamyatin (we are convinced still more strongly of this below) symbolize the struggle between these two elements. And from this point of view Zamyatin is unconditionally a symbolist who has set himself the goal of dressing the laws of physics and chemistry in the analytical means. Therefore his style manifests living folk skaz, mod ernized colloquial speech, and squareness of images—quadrangular, square, straight, flat-iron-like, and so forth. The two forces engage in an endless struggle, but one—the force of inertia, tradition, peace, equilibrium—weighs down the other, destructive, force with heavy layers, like the earth’s crust, easing and forging a molten fiery element. Peace and equilibrium are found in the sleepy Tale of the Provinces, in the life of the Craggses and that of the Dooley couple. Only in certain rare instants are vents opened and does the crust break; and then the stormy underground force of destruction gushes forth like lava from a volcano. But usually the cold, petrified, numb forces reign. Only such rare moments are valuable and significant. Zamyatin tells mainly about them; they are the axis of his artistic creation. This force and the “instants” assume in Zamyatin the most varied images, shapes, and forms. Marusia with her meaningless conversations about the spider web and death, which are imprinted forever in the soul of Andrei Ivanovich; the capricious Didi; the fiery redhead Pelka in “The North” (Sever); the heroine number such-and-such in the novel We. They personify what is most necessary and valuable: from them emanates, and through them speaks the genuine force of life, its womb and its most holy of holies. From them come uprisings and ruptures in things of set dimensions which have always been overgrown with moss. In the short story “The Land

34

Alexander Voronsky

Surveyor” (Zemlemer) the hero can find no way to say that he loves Lizaveta Petrovna. The “moment” arrives when out of mischief some lads have smeared the dog "Funtik” with paint. The girl begins to feel sorry for the dog, tears begin to flow, and then “the surveyor forgot about everything and began to stroke Lizaveta Petrovna’s hair.” Then the surveyor is about to have to spend a night with the girl in one room in a monastery, and had this happened they would have remained together. But the nanny arrives, and everything is over: “That’s how it had to be.” In “A Fisher of Men” such a moment occurs when the Zeppelins are over London. Crashing bombs burst into the thoroughly regulated life of the Craggses, and the usual balanced and settled way of life collapses. The “curtain” is drawn over Mrs. Lorry’s lips, and a pianist, the good-for-nothing Bailey, kisses her with lips “as tender as a colt’s,” and Mrs. Lorry responds in kind. But that is only an instant: “The cast-iron feet fell silent somewhere in the south. Everything was over.” In “The Protectress of Sinners” (Spodruchnista greshnykh), during the revolution peasants break into the Mother Superior’s quarters of a cer tain monastery with the intention of stealing, but at the very decisive moment the "reverend mother" in an especially touching way treats the malefactors to pies and something else, and the bloody deed is shattered. In “The Dragon," the dragonman (a Red Army man) has just told in a streetcar how he dispatched “an intellectual mug,” “without transfer, into the kingdom of heaven.” Suddenly he sees a sparrow freezing in a corner of the streetcar. The dragon, his rifle fallen to the floor, warms the sparrow with all his might, and when the sparrow flies away, the “dragon's" mouth opens in an ear-to-ear grin. The world is like a dog (“Eyes”): it has a mangy fur coat, it cannot speak, but only barks, it zealously guards its master’s property (the property is guarded for a little dish of rotten meat); it breaks away from his chain and slowly, pitifully, and full of guilt, with its tail between its legs, drags itself along to its master’s kennel. But. . . “such beautiful eyes. And in those eyes, in the depths, such sad human wisdom ..." Sometimes there are sailors of the Potemkin ("Three Days”), but more often Didi, O'Kelly, Senia, and others. The sailors of the Potemkin are entirely outside Zamyatin’s field of vision. He was born and grew up in A Tale of the Provinces, and his people are for the most part found in the images of the Arzhanoys, the Timokhas, the Neprotoshnys, the drunkard Guslyaikins, the lads who out of boredom half-drown a boy by pouring water over him, or who perform experiments with paint and a dog, or peasants who rebel against cheese (“we ate close to five pounds of that very same soap”). In Zamyatin there is no peasant who looks different as, for instance, there is in the partisan stories of Vsevo

Evgeny Zamyatin

35

lod Ivanov. Zamyatin cannot look at what is around him through the eyes of these sailors, peasants, and workers. It is interesting that in his reminiscences of the Potemkin days the author also concentrates his attention on only an instant—three days—when it seemed that every thing was breaking away from the shores. The moment is therefore valuable to him. No general connection is felt between these days and the revolution. The author does not need that. This is why in “The Islanders” and “A Fisher of Men” Didi, O’Kelly, and even Campbell introduce a rebellious element into the thoroughly regulated life of the Craggses and the Dooleys. The rebellion turns out not to be very dangerous, since the tops, and not the roots are taken. Poignant, but permissible. The rebellion is loyal—it is not that rebellion of which sailors, workers, and peasants are capable. After all there is only dissolution here, a narrowly individualistic protest, as a result of which the foundations will not be shaken. The writer is concerned with that: for him it is necessary to juxtapose to thoroughly regulated life moments of individual rebellion, small and insignificant and intimate, which the author nonetheless values and remembers most of all. In A Tale of the Provinces and “At the World’s End” the protests and the struggle are also personal and are carried on by persons acting alone. The writer completely fails to see, mention, or value other forms. There the struggle always ends in defeat. It cannot be otherwise when exclu sively individual considerations are put foremost. In our time, we repeat, this is too little and is superficial. And when an artist is inclined toward political lampoons, it is possible to anticipate that he will experience failures. Nevertheless, both “The Islanders” and "A Fisher of Men” remain masterful artistic lampoons, in spite of their limited significance. The writer’s London works, like A Tale of the Provinces, “At the World’s End,” and "Alatyr,” will remain in our literature. We must also bear in mind the fact that "The Islanders” came off the press when many fellow writers, considering themselves the preservers of the testaments of all Russian literature, perceived in the likes of Vicar Dooley and Mister Craggs the bearers of humaneness and humanity, and of other virtues which are not in keeping with those insidious Bolsheviks. Zamyatin did not stick to his noble, truly and only “mutinous” position later. But about that below. The artistic merits of “The Islanders” and “A Fisher of Men” are indubitable. The capability of rendering image and character with one device is consolidated in hardened form. It is as if Vicar Dooley and Mister Craggs were forged. Zamyatin is an artist-experimenter, but a special experimenter. With him the experiment is taken to extremes, to

36

Alexander Voronsky

the limit. It is, so to speak, an experiment in the pure form. In his style Zamyatin departed from modernized folk skaz: it is necessary to do that in a story about London. For the first time the artist renders that clipped and condensed style with dashes, omissions, hints, and things left unsaid, that intricate work on the word and that admiration for it, that semi-imaginism—all of which have later been strongly reflected in the work of the majority of the Serapions. It is painstaking work to the point of small details, so laborious that one must maintain a constant effort and must read every line intently. This is wearisome; at times it even leads to affectation and satiety, as though the author were playing with his handicraft.

Ill

In the short story “The Good-for-Nothing” the following conversa tion takes place between a conspirator, the underground figure Isav, and Senia the good-for-nothing: Isav was saying: “And how is it possible to believe in anything? I only assume and act. A working hypothesis, you understand?" Peter Petrovich turned to Senia: "Well, and you?" “Me-e? What, are you crazy? That I... If I had my way I wouldn’t even look at all their programs. Thank God, at long last we busted loose from those shores, but now they want to drive us back. And I say if there is an overflow, then let it be for real, like on the Volga ....”

In accordance with this, the good-for-nothing Senia is given an obvious moral preponderance: Senia heroically perishes on the barricades, and Isav philosophizes on the occasion of his senseless death, although the author does not refuse Isav his cold, even inimical respect. The attitude “I wouldn’t even look at all their programs” flows forth organically from the writer’s entire artistic outlook. As we saw earlier, Zamyatin approached the complex phenomena of social life with a physical theory about two forces in the world: entropy and energy. Moreover, it has turned out in his work that the destructive element functions at “moments,” in “incidents,” and in individual, intimate im pulses of the human spirit. The artist has also approached the Russian revolution with this measuring stick. The result has been what it must be on these occasions. As applied to society this theory of two forces is not so much

Evgeny Zamyatin

37

untrue as it is abstract, and therefore untrue as well. There are insignifi cant cliches containing nothing concrete; living life flows away here, like water between the fingers. As a matter of fact a dead scheme has been applied to whatever has been found suitable: abstract rebelliousness, revolutionism, and heresy in the name of heresy. The “flood,” “agonizingly perpetual motion," “asceticism”—this is all very empty, insignificant, and abstract. This abstract rebelliousness weakened the artist to a greater extent in “The Islanders,” as well as in A Tale of the Provinces and “At the World’s End." It led to a fundamental misunder standing in the writer’s attitudes toward the Russian revolution. This is the way it had to happen. As soon as a “heretic" tried to descend to earth from the mountainous heights in the name of “heresy,” great discord resulted. It turned out that “their programs," those of the peasants, the workers, and the masses, also existed on the “rebellious” earth, and concrete “earthly” targets were established on earth. They were in general very little interested in intimate, personal rebellion. Instead, they prepared and set in motion the most enormous collectives: Communists, the Red Army and others. Historically and socialistically, abstract revolutionism and so-called spiritual maximal ism have expressed the intelligentsia’s rosy pre-revolutionary romanticism, and even before the revolution they pointed out the essential discord between the ideal and the real in the consciousness of broad circles of the intelligentsia. The liquidation of the autocracy was thought to be necessary and desirable, but on the other hand even then the intelligentsia viewed the elemental Bolshevism of the workers and peasants with fear. Thus arose the desire to see the revolution as noble, and not made by the coarse hand of the peasant and the worker, but rather by clean hands with polished nails. As soon as it was disco vered that this would not be the case, but that the revolution would be rough-hewn, the rebelliousness of the Russian O’Kellys and Senkas vanished most rapidly, like smoke. Spiritual maximalism and the fier cest heresy were suddenly left somewhere beyond the bounds of the revolution, and it was discovered that maximalism had “a soul small in appearance and by no means immortal,” that world-wide revolutionism looks very (even extremely) cultured, moderate, and neat, that it pre sumes to conquer the heavens and not the sinful earth, that this was said about the revolution of the spirit in some sort of special fiery transformation—and not about “that republic," or whatever it is called—and that it was said about the intimate and all-cleansing moments. And they were not to plunder country estates, or take away factories, or carry valuable cultural objects off to their huts, etc., etc. In Zamyatin we see seemingly implacable rebelliousness, fun-

38

Alexander Voronsky

damental and indefatigable, we see people in the images of the Arzhanoys and the Guslyaikins, we see a looking to the ideal as to something irreparably torn away from the earth (the acknowledgement of revolu tion in the spirit, in intimate moments), alienation, cold remoteness from the genuine face of the revolution, and hostility to it. Be that as it may, after October Zamyatin wrote a number of stories and tales which afforded undoubtable satisfaction to the most violent enemies of October, and great and sincere chagrin and indignation to those who knew and valued his talent: "The Dragon,” "Mamai,” “The Cave,” “The Church of God,” “The Moors,” (Arapy), “The Protectress of Sinners,” and finally, the novel We. The most talented of these works is "The Cave," and the most serious is We. We have happened to hear the objection that it is very rash and premature to paint Zamyatin’s recent works white: not every satire is White propaganda, and not everything which is dressed in red is genuine revolution. That is so. There really does exist among us a fear of touching upon the sore spots of the Soviet mode of life. We must fight this fear in every way possible. The following often happens: people are long silent, and all of a sudden they begin to sound the alarm (let’s say over a bribe, for example). And there are quite a few weak-willed indi viduals to be found, too. If Zamyatin had written his caustic works while remaining on the soil of the revolution, it would only be possible to hail him. Unfortunately, things are not that way at all. Zamyatin has approached the October Revolution obliquely, coldly, and with hostility, it is alien to him not in its details, even if they are essentially important, but as a whole. In the strange, unfamiliar city of Petrograd the passengers wandered in confusion. In some ways it was like, and in some ways unlike, the Petersburg from which they had been sailing for almost a year now, and to which, God knows, they would return some day .. . Australian warriors in strange rags, their weapons on ropes behind their shoulders . . . Australians with red faces were pushing into the opening with enormous bags (“Mamai").

And again: On the streetcar platform a dragon with a rifle flashed briefly, rushing into the unknown. His cap fit down over his nose and would of course have swallowed up his head if it were not for his ears; the cap had settled on the protruding ears.... And a hole in fog: his mouth ("The Dragon").

In "The Moors” the dragons and the Australians are called redskins. Only a citizen-passenger of the republic, who on the

Evgeny Zamyatin

39