Fire on the Island: Fear, Hope and a Christian Revival in Vanuatu 9781800734654

In 2014, the island of Ahamb in Vanuatu became the scene of a startling Christian revival movement led by thirty childre

176 42 95MB

English Pages 276 [240] Year 2022

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Acknowledgements

Notes on Text

Chronology: The Revival Process

Maps

Figure

Introduction. Fear, Hope and Social Movements

Chapter 1. Life and Death

Chapter 2. Love and Land

Chapter 3. The Revival Begins

Chapter 4. Gender and Integrity

Chapter 5. Spiritual War

Chapter 6. Crises and Reconciliations

Chapter 7. Hope, Blame and New Possibilities

Conclusion

Appendix: ‘Jesus, You Are My Helper’

Glossary

References

Index

Citation preview

FIRE ON THE ISLAND

ASAO Studies in Pacific Anthropology General Editor: Rupert Stasch, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge The Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania (ASAO) is an international organization dedicated to studies of Pacific cultures, societies and histories. This series publishes monographs and thematic collections on topics of global and comparative significance, grounded in anthropological fieldwork in Pacific locations. Recent volumes: Volume 13

Volume 8

Fire on the Island: Fear, Hope and a Christian Revival in Vanuatu Tom Bratrud

Mimesis and Pacific Transcultural Encounters: Making Likenesses in Time, Trade, and Ritual Reconfigurations Edited by Jeannette Mageo and Elfriede Hermann

Volume 12

In Memory of Times to Come: Ironies of History in Southeastern Papua New Guinea Melissa Demian Volume 11

Authenticity and Authorship in Pacific Island Encounters: New Lives of Old Imaginaries Edited by Jeannette Mageo and Bruce Knauft Volume 10

Money Games: Gambling in a Papua New Guinea Town Anthony J. Pickles Volume 9

Dreams Made Small: The Education of Papuan Highlanders in Indonesia Jenny Munro

Volume 7

Mortuary Dialogues: Death Ritual and the Reproduction of Moral Communities in Pacific Modernities Edited by David Lipset and Eric K. Silverman Volume 6

Engaging with Strangers: Love and Violence in the Rural Solomon Islands Debra McDougall Volume 5

The Polynesian Iconoclasm: Religious Revolution and the Seasonality of Power Jeffrey Sissons Volume 4

Creating a Nation with Cloth: Women, Wealth, and Tradition in the Tongan Diaspora Ping-Ann Addo

For a full volume listing, please see the series page on our website: https://www.berghahnbooks.com/series/asao

Fire on the Island Fear, Hope and a Christian Revival in Vanuatu

• Tom Bratrud

berghahn NEW YORK • OXFORD www.berghahnbooks.com

First published in 2022 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com

© 2022 Tom Bratrud

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. cataloging record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number: 2022004816

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-80073-464-7 hardback ISBN 978-1-80073-465-4 ebook

For my family in Norway and Vanuatu

Contents

List of Illustrations Preface Acknowledgements Notes on Text Chronology: The Revival Process Introduction. Fear, Hope and Social Movements

•

viii x xv xviii xxi 1

Chapter 1. Life and Death

15

Chapter 2. Love and Land

40

Chapter 3. The Revival Begins

65

Chapter 4. Gender and Integrity

87

Chapter 5. Spiritual War

108

Chapter 6. Crises and Reconciliations

130

Chapter 7. Hope, Blame and New Possibilities

153

Conclusion

175

Appendix: ‘Jesus, You Are My Helper’

183

Glossary

184

References

189

Index

206

Illustrations

•

Figures

0.1. Phelix on mainland Malekula with Ahamb Island in the back. Photo by the author. 0.2. Women and children during a revival event in the Ahamb Presbyterian community church. Photo by the author.

xxvi 5

1.1. The sorcery trial that took place on 23 June 2014 following the sudden and surprising death of the four-year-old boy, Eliot. Photo by the author.

25

1.2. The opening ceremony of the revival convention for all Presbyterian Churches in Malekula, Farun village, September 2014. Photo by the author.

26

2.1. Eilen performing love (soemaot lav) when giving out freshly baked bread during a fundraiser to prepare a relative’s wedding. Photo by the author.

44

2.2. Custom ceremony to appoint the new hae jif on Chiefs’ Day, 5 March 2014, two weeks before the revival was initiated. Photo by the author.

61

2.3. A sculpture in front of the Ahamb community church. Photo by the author.

62

3.1. Ahamb people following the revival introductory programme. Photo by the author.

77

4.1. South Malekulan societies follow a patrilocal residence practice. Women ‘marry out’ and live in different nasara, but often meet to do collaborative work. Here, Lena (left), has gathered a group of women to cook and chat in her natal village of Merirau. Photo by the author.

90

4.2. Isacky initiating a kava ceremony to express gratitude and respect to Jakon, who had been successful in treating his mother’s sickness with herbal medicine (lif ). Photo by the author.

91

Illustrations

ix

4.3. Two young men are stopped in the screening for having tu tingting. Here, the men are praying for forgiveness with the visionary children after instructions from the latter. Photo by the author.

103

5.1. Visionaries saw that a group of sorcerers were flying in by su towards Ahamb. A group here is praying against the flying sorcerers, holding up a Bible in their direction. Photo by the author.

118

5.2. Children working in the house of Parker and Jane. Photo by the author.

119

5.3. Children and adults mobilise after visionaries reported that flying sorcerers had landed in a tree nearby. Photo by the author.

120

5.4. After a long day of chasing invisible sorcerers who had allegedly landed on Ahamb to try to kill someone, the visionaries declared that the sorcerers had flown away. Photo by the author.

121

6.1. The grand reconciliation ceremony between the community and Eneton on 9 November 2017. Photo by the author.

146

7.1. A number of visionary children are lining up to convey their revelations to the congregation. Children and women are laying slen on the floor after being filled with the Holy Spirit. Photo by the author.

163

Maps

0.1. Vanuatu in the Southwest Pacific. Map produced with the permission of CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University.

xxiii

0.2. Malekula, also spelled Malakula, in Vanuatu. Map produced with the permission of CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University.

xxiv

0.3. South Malekula with Ahamb Island in the centre. Map by Tine Bratrud.

xxv

Preface

•

‘What’s that?’, Jelen suddenly exclaimed. She froze and a worried look appeared on her face. Then I heard it too: the loud noise of crying, howling and screaming. The overwhelming sound was accompanied by a choir of voices intensely singing a prayer, as if trying to repel the distress that was causing the crying: Hiling han blong Jisas hemi tambu tumas! Sapos yu nidim bae i save hilim yu! Han blong hem i fulap long ol meresin Hiling han blong Jisas hemi tambu tumas!

The healing hand of Jesus is very Holy! If you need it He can heal you! His hand is filled with medicine The healing hand of Jesus is very Holy indeed!

The scene took place one afternoon in late May 2014 on the small island of Ahamb, just off the south coast of Malekula in the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu. It was five months into my second fieldwork on the island, and I was sitting outside the house of my Ahamb adoptive parents, Jelen and Herold, with a group of neighbours. As we often had done over the past few months, we had taken a break from our daily routines to chat about recent happenings that seemed to be turning life on the island upside down: little children had become trusted religious leaders and focal points of the community; inveterate land claimers were voluntarily giving away land to political opponents in public ceremonies; women, who normally have no position from which they can address men in public, were reprimanding male community leaders on a daily basis; and sorcerers, who normally operate in secret, were handing over their remedies to the community. These happenings were all part of a startling Christian revival movement that had dominated much of island life over the past two months. A main characteristic of the revival was that it was led by about thirty children with spiritual gifts who, for a total of nine months, were offering daily messages from the Holy Spirit to the community about who was blessed, who was cursed and what evil needed to be defeated so that people could receive salvation as the Last Days were drawing near. The revival was frequently talked about as ‘cleaning the island’ (klinim aelen), as it developed in the wake of enduring political disputes and division in the community. The visionary children proclaimed that if people opened their hearts to the Holy Spirit, its presence would be able to change the very fabric of life on the island, including the

Preface

xi

pressing disputes, the division they caused and the sorcery attacks that often follow on from such disputes. The crying we heard from the village made us uneasy for a specific reason. Emily, a visionary girl of eight years old, had suddenly fallen sick and fainted in church the night before. While sitting seemingly unconscious on the lap of her worried father, she had been shaking and turning restlessly around. Her sudden and inexplicable condition was attributed to sorcery, which was believed to have had a dramatic upsurge in the past week. The upturn of sorcery had begun when a group of visionary children found a stone they claimed was infused with sorcery (baho or posen) outside the island’s community hall. The children stated that the stone was placed there by ill-meaning sorcerers, who were normally political opponents to some Ahamb leaders, in order to create division in the community. Sorcery is a highly concealed endeavour in Vanuatu and is perhaps what Ahamb people fear most in their everyday lives as it is used to secretly injure and kill. The finding of the stone marked the beginning of an intense period where the community, after instructions from the visionaries, started removing supposed sorcery objects meant to hurt the islanders. In response, the visionaries conveyed that a grand network of furious sorcerers mobilised to attack people on Ahamb, particularly the children who were responsible for taking away the sorcerers’ powers. The fear of the sorcerers mobilised the community in a range of activities to protect the children and one another. As I will discuss in this book, people’s fear of sorcery, alongside their hopes of making an end to the insecurity it was causing, became a potent driving force of the revival movement for several months. It also led to the tragic murder of two men believed to be sorcerers and responsible for many of the island community’s problems. At Jelen and Herold’s, my relatives and I feared that the sudden crying, screaming and praying meant we had lost Emily to her condition, whatever its cause. We agreed that I should go and find out what was going on. Following the enduring sounds, I ended up in the yard of Sebastian and Lena, a couple in their late thirties. The yard was packed with people. Behind their house was a busy and lively scene with rows of onlookers standing around a big tree. The tree had been climbed by two men who held torches in their mouths and looked restlessly around. On the ground were around fifteen visionary children who were crying, shaking and conveying visions and messages – supposedly from the Holy Spirit – to the crowd and the men in the tree. Occasionally, some of the children fainted and fell to the ground, indicating that they were ‘slain in the Spirit’, meaning to be struck and overcome by the powers of the Holy Spirit. In several places in this book, I refer to Vanuatu people’s own verb to slen to describe this reaction. In Chapter 1, I also describe how I came to slen myself during a ceremony, which shows how my own psyche as an ethnographer was not left untouched by taking part in the startling revival events.

xii Preface

While watching the scene unfold in Sebastian and Lena’s yard, fellow onlookers explained to me that the visionary children had seen, through their spiritual vision, four men in the yard who wanted to kill Sebastian. The men were using sorcery and had taken the form of a cat in order to enter the yard without raising neighbours’ suspicions. However, at the moment, the men seemed to have made themselves invisible, which is yet another ability ascribed to sorcerers. People speculated if the men wanted to kill Sebastian because of his prominent position as a councillor in the provincial government, to which he had been appointed a few months earlier. Holding a prestigious position is often found risky in Vanuatu because it can be weaved into previous status rivalries and political conflicts. It can also cause resentment in kin and others to whom one engages in reciprocal commitments if they feel overlooked in allocations of resources and opportunity. Sorcery can then be used to bring down an opponent and level out difference. During the revival, the visionaries were attacking sorcery as a destructive symptom of such rivalry and inequality, but also the principles on which such rivalry and inequality rested, mainly disputes over land rights and leadership, which I will discuss in Chapter 2. According to the visionaries, two of the four sorcerers who planned to kill Sebastian were now up in the tree, but had taken the form of lizards. That is why the two men with torches had climbed the tree – they were looking for the sorcerers in lizard form. The crying and shaking children on the ground were occasionally conveying visions about the whereabouts of the sorcerers to the men in the tree and people on the ground shining their torches frantically around in response. Suddenly, a big lizard fell down from the tree. People jumped to all sides and the lizard ran and disappeared into a bush. Men and boys ran after with machetes, cutting the plants around them in the direction it had run. An intense hunt for the lizard ensued, supported by loud and energetic prayers from the crowd to make the Holy Spirit’s powers stop it from getting away. After some intense minutes, a group of men eventually managed to kill the lizard. The killing brought a sigh of relief after what had, for most participants, been a quite obscure situation forced upon them that afternoon. However, after a few minutes’ break, the visionaries were again crying desperately, screaming and shaking. They were pointing towards something that was seemingly moving quickly on the ground towards Sebastian and Lena’s house. Amanda, a visionary girl aged thirteen, suddenly jumped in the air while wriggling and shouting that her body was itching. The itching, we had learned, was a reaction of the visionaries after coming into contact with a sorcerer, a sorcery object or a spirit used for sorcery. The visionary children shouted and pointed to the ground, indicating that the sorcerer who had struck Amanda was about to escape. The men with machetes immediately started pulling up plants by their roots, cutting them down and digging into the ground after directions from the visionaries, but without any luck. Following the unsuccessful

Preface

xiii

search for this sorcerer, some men suddenly started cutting down a big tree in Sebastian and Lena’s yard. The children had stated that it was used as a landing place for sorcerers coming to the island by su, the sorcery of flying, commonly used by sorcerer assassins. The tree had to be removed in order to reduce the risk of future sorcery attacks on the island. After a few hours in Sebastian and Lena’s yard, most of us continued to Ahamb’s Presbyterian community church for the evening’s revival worship service. The revival services were a nightly event held to nurture the presence of the Holy Spirit and get the latest updates from the visionaries. After prayers and singing of worship songs, a number of visionary children conveyed messages and visions from the Holy Spirit about the events in the yard. John, one of my good friends and interlocutors – and Sebastian and Lena’s neighbour – also rose to explain how it all started when some visionary girls had seen a cat by Sebastian and Lena’s house, claiming that it contained one or more sorcerers in disguise. John had grabbed his Bible and joined the visionaries in praying to neutralise the sorcerers’ powers and chase them away, upon which the cat had disappeared, but all of a sudden, in invisible form, he claimed, jumped on his chest. He had felt the weight of it. Other onlookers then shared their experiences. Many reported that the revival was making them simultaneously cheerful, amazed and afraid. It showed them things, and brought them into situations, that they had never experienced before. After the worship service, a thirteen-year-old visionary girl I call Sophie became distracted and suddenly started to scream and cry out loud. Her father came to hold her and calm her down. Other people were also gathering around her to see what was wrong. While crying and turning to her father’s chest, Sophie explained that one of the sorcerers preying upon the children was standing outside the church, waving his hand to call for her because he wanted to kill her. We who were present turned our heads to see what was outside. There stood Ahamb’s long-time sorcery suspect, a man in his sixties I call Orwell. During the revival, the visionaries pointed him out as responsible for many of the district’s unexplainable deaths and troubles over the past two decades. Visionaries also conveyed that he was a leading figure in the sorcerers’ raids to kill the island’s children during the revival. In Chapter 1, I will show how Orwell was eventually targeted and killed by a furious mob for allegedly having caused more than thirty deaths and numerous instances of sickness and misfortune on Ahamb and elsewhere in South Malekula over the past few decades. Since Orwell appeared to be pivotal to the community’s crisis, something about his critical behaviour had to be changed in order to improve the community’s situation. In context of the existential panic that arose, his murder took the form of a sacrifice that, in René Girard’s (2013) terms, was necessary to transform people’s dread and to heal the community (see also Rio 2014a).

xiv Preface

As I will show in the forthcoming chapters, the revival raised many existential questions and answers during its course. It took the community to the point of its collapse, but also to its point of renewal. In the spectacle of the revival, everything seemed to be at stake. It revealed the whole spectrum of cosmic forces and all truths. There was no distinction between symbol and reality, ‘each realising the existential, apocalyptic potency of the other’ (Kapferer 2015b: 94). Trying to understand the revival, including the circumstances under which it emerged and gained so much impact, raises several intriguing questions: how can social upheavals like the Ahamb revival emerge? How can children, who are usually on the lowest level in a social hierarchy, become a renewal movement’s leaders? How can violence be performed in the name of love by people who normally insist that violence is the antithesis of love? How may social movements become a venue in which social problems can be addressed and possibly resolved, while simultaneously carrying the risk of exacerbating the same problems they aim to address? These are some of the questions I will try to answer in this book.

Acknowledgements

•

To make this book possible, I have benefited over the years from the help of so many people, many more than I will be able to mention by name. On Ahamb I have met some of the finest human beings I have ever known, and I will begin with them. I want to thank all Ahamb people for inviting me to live with them during my three periods of fieldwork in 2010, 2014 and 2017. It would require several pages to mention all the individuals who helped me in their different ways, so I will only specify those who became my closest families and helpers. Chief Herold and Jelen, Felix and Lestiny, Kelly, Kathy, Alfred, Marie and Jeremiah. Abel and Espel, Rehap, Bethy and Nixon. The late tötöt Vanny, tötöt Tomsen and kakaf Leto. Tötöt Morvel, tötöt Peter and kakaf Lena. Markai and Merisan. The late Elder Colin and Manatu. Albert and Elise. The late Dickson and Erlyn and all my remaining family in Turak. Graham and Neto. Chief Hedrick and Niely, Tina, Tavina, Jim, Lita and everyone in Meliambor. Pastor Herbert and Gracy. Javet and Erin. Jameson and Markina. Fedrick, Cleta, Jakon, Skepson and everyone in Robanias. Elder Joe, Mirekel, Kalmase and Maryan in Lamburbagor. Chief Kaltau and Vivian with family in Lijongjong. David, Morlin, Unel and everyone in Merirau. The late Lennart in Barmbismur. Jim Knox in Luwoimalngei. Elder John Silik and everyone in Renaur. Chief Johnlamb, Keith, John Kenson and everyone in Rembue. Elder Charlie, Chief Redely, Elder Welken and everyone in Barmar. A big thank you to everyone else I have engaged with in South Malekula for your hospitality and collaboration. In Port Vila, I must thank Col and Anita, Kelvin, Michael, Lydia and everyone in Freswota. John and Vilen in Platiniere. Chief Harry, Rosine and Rolynne in Agathis. MP John Sala, John Graham and their families. Thomas and his family in Manples. Osbourne and the squad. Dorin, Kency and everyone I met from South West Bay. Thank you to Elder Bernard, Elder Roy, Elder Gideon Paul and Pastor Sivi. Hildur Thorarensen, Kristine Sunde Fauske, Michael Franjieh and Daniela Kraemer, thank you for the company and discussions in Vila. Thank you to the former directors at the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Ralph Regenvanu and Marcellin Abong, as well as Brian Phillips at the Department of Meteorology, for making the research possible. Thorgeir Storesund Kolshus and Signe Howell have been my long-time mentors and I am deeply thankful for their intellectual encouragement, constructive critique and support over the years. I have benefited greatly from the interest and support of Joel Robbins and I thank him for our good conversations and his encouragement and valuable suggestions. I am grateful to Nils

xvi Acknowledgements

Bubandt and Arndt Schneider for their critical reading of the material in this book and their suggestions on how it could be improved. I thank the editor of the ASAO book series, Rupert Stasch, whose enthusiasm has been key in moving this manuscript forward. I would also like to thank the staff at Berghahn Books, especially Tom Bonnington, Elizabeth Martinez and Keara Hagerty for their engagement in making the book a reality and Jan Rensel for her copyediting and excellent cooperation. I also thank my anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and insights. Their input has without doubt helped to improve the manuscript. I am grateful to the whole academic and administrative staff at the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo. I would have liked to mention all their names, but will limit myself to those who have been directly engaged with my work over the years: Cato Berg, Kathrine Blindheimsvik, Cecilie Fagerlid, Rune Flikke, Paul Wenzel Geissler, Kirsten I. Greiner, Maria Guzman-Gallegos, Christian Krohn Hansen, Ingjerd Hoëm, Gyro Anna Holen, Marianne E. Lien, Nefissa Naguib, Knut Nustad, Jon Henrik Ziegler Remme, Nina Rundgren, Mette K. Stenberg, Arve Sørum, Elisabeth Vik, Halvard Vike and Unni Wikan. Matt Tomlinson and Keir Martin have been particularly generous in reading and discussing parts of the book with me. A big thank you to my peers during the doctoral period for the fellowship and for all our discussions: Mónica Amador, Eirik B.R. Anfinsen, Aleksandra Bartoszko, Ola Gunhildsrud Berta, Tuva Broch, Jonas Kuer Buer, Lotte Danielsen, Rune Espeland, Martine Greek, Lena Gross, Nina Alnes Haslie, Kaja Berg Hjukse, Tone Høgblad, Samira Marty, Sara Alejandra M. Monter, Anita Nordeide, Robert Pijipers, Cecilia Salinas, Mikkel Vindegg, Ståle Wig and Kimberly Wynne. I have benefited from several visits and discussions with the people at the Department of Social Anthropology at University of Bergen over the years. Thank you to everyone there, particularly Eilin Holtan Torgersen and Edvard Hviding at the Bergen Pacific Studies Research Group. A special thanks to Annelin Eriksen and Knut M. Rio for all your generosity, encouragement, and intellectual and practical guidance over the years since I started preparing for my initial fieldwork in Vanuatu. I have also benefited from the encouragement of other fine scholars whom I have been fortunate to discuss my work with, among them Ruy Blanes, Matthew Engelke, Carlos Fausto, Miranda Forsyth, Naomi Haynes, Susanne Kuehling, Lamont Lindstrom, Michelle MacCarthy, Birgit Meyer, Carlos Mondragon, Michael Scott, Rachel Smith, Marc Tabani, Howard van Trease and Aparecida Vilaça. Thank you all. I am indebted to linguist Tihomir Rangelov who helped me prepare the section on the Ahamb language. Tihomir and I met in Port Vila during my 2014 fieldwork and we quickly started discussing the possibility of him documenting the Ahamb language. Our ideas became a reality, and Tihomir started his fieldwork on Ahamb in 2017. His dissertation on Ahamb grammar was

Acknowledgements

xvii

successfully defended in 2021. He has also provided me with updates from the island and been a helpful discussion partner. Thank you Halfdan Gimle, Mari Nythun Utheim, Åsmund Sveinsson, Jake Leyland, Jasmin Bubric, Susanne Roald, P.K-folket, Uglelaget and Eirin Breie for all your support, in various ways, during my work on this book. Thanks to my wonderful family Tage, Tine, Bjørg and Terje Bratrud for constant encouragement and support, and for always being there for me. The research in this book would not have been possible without the funding from the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo, Signe Howell’s Fieldwork Scholarship for Master Students, the Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture and the Norwegian State Educational Loan Fund. It goes without saying that I am tremendously grateful to these institutions for giving me the opportunity to carry out this research. Kerstin Bornholdt and Thor Christian Bjørnstad gave me time to work on the book manuscript while I was employed at the Department of Culture, Religion and Social Studies at the University of South-Eastern Norway. I thank them both for their generosity and understanding. Thanks also to Marianne E. Lien for giving me time to complete the book manuscript after I started as Postdoctoral Fellow in the project ‘Private Lives: Embedding Sociality at Digital “Kitchen-Tables”’ at the Department of Social Anthropology, University of Oslo. Valdres Museum has provided me with office space during several periods of writing, and I thank director Ole Aastad Bråten and the rest of the staff for their hospitality. Earlier versions of some arguments and passages have appeared in other published forms. Parts of Chapter 2 appear in ‘What is Love? The Complex Relation between Values and Practice in Vanuatu’, published in 2021 in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 27(3): 461–77 (DOI: 10.1111/14679655.13546) and in ‘Asserting Land, Estranging Kin: On Competing Relations of Dependence’ published in 2021 in Oceania 91(2): 280–95 (DOI: 10.1002/ ocea.5305). Parts of Chapter 4 appear in ‘Ambiguities in a Charismatic Revival: Inverting Gender, Age and Power Relations in Vanuatu’, published in 2019 in Ethnos (DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2019.1696855). Parts of Chapter 5 appear in ‘Fear and Hope in Vanuatu Pentecostalism’, published in 2019 in Paideuma 65(1): 111–32 and in ‘Spiritual War: Revival, Child Prophecies and a Battle over Sorcery in Vanuatu’ in Knut Rio, Michelle MacCarthy and Ruy Blanes (eds), Pentecostalism and Witchcraft: Spiritual Warfare in Africa and Melanesia, published in 2017 by Palgrave Macmillan (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/9783-319-56068-7_9) (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Parts of Chapter 7 appear in ‘Paradoxes of (In)Security in Vanuatu and Beyond’, published in 2020 in Journal of Extreme Anthropology 4(1): 177–97 (DOI: https:// doi.org/10.5617/jea.7395). I thank the publishers of these works for making it possible to reproduce or rework elements of them for inclusion in this book.

Notes on Text

•

Language

Ahamb islanders have their own vernacular, referred to by its speakers as naujin sdrato (our language) or as ‘the Ahamb language’ in the linguistic literature (Glottolog code: axam1237, ISO 639-3 code: ahb). The language is one of over thirty Malekulan languages spoken today, and one of over 120 vernacular languages spoken in Vanuatu, the most linguistically diverse country in the world in terms of number of languages per capita (Lynch 1994). Ahamb is a member of the Oceanic sub-branch of the Austronesian language family. Oceanic languages are further subdivided into a number of branches, and Ahamb is in one subgroup with most other languages of central Vanuatu. The Ahamb language has around 950 speakers, most of whom live on Ahamb island (Rangelov, Bratrud and Barbour 2019). Smaller pockets of speakers live on the adjacent mainland of Malekula and in the urban centres, mostly in Port Vila, but also some in Luganville. All members of the Ahamb community also speak Vanuatu’s national language, Bislama, which is widely used, especially among young people, in church, in meetings and in households where one spouse is from another ethnolinguistic group. While Ahamb is the most common language of communication at home, code switching with Bislama is very common. Most Ahamb people today also speak some English, and English is the language of instruction in school from Grade 3 onwards (Bislama is used as the medium of instruction in the first three years of primary education). The Ahamb language borrows heavily from both Bislama and English. My fieldwork was conducted mainly in Bislama, supplemented with words and phrases in the vernacular. I set out to learn the vernacular properly during my second fieldwork, but the revival events compromised my own and my interlocutors’ time and attention to do proper language sessions. In meetings where the vernacular was used, I was for the most part able to follow what was going on, but depended on having the details explained to me afterwards. In the book, terms in Bislama are given in italics and underlined, while terms in the Ahamb language are given in plain italics. Ahamb is rarely written; however, work on standardising an orthography for Ahamb has been going on since 2017, when linguist Tihomir Rangelov started a Ph.D. project to document the Ahamb language. Tihomir has since published a comprehensive grammatical description of Ahamb (Rangelov

Notes on Text

xix

2020a) based on a corpus of annotated Ahamb speech from different genres and other Ahamb texts. The corpus is openly available through the Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR) (Rangelov 2020b). A draft Ahamb-BislamaEnglish dictionary is in development and Tihomir has also been working with the community on creating literacy materials in order to boost the status of the Ahamb language and contribute to its maintenance and revitalisation. Tihomir and I have been communicating closely since we first met in Port Vila during my fieldwork in 2014, and his work has been very helpful in clarifying my own uncertainties regarding the Ahamb language. The basic grammatical structure of Ahamb is mostly typical of Oceanic languages (see Lynch et al. 2002). Nouns lack inflection for number or case, but they usually feature a noun marker (historically an article). Possessive constructions are complex and depend on a semantical distinction between inalienable (e.g. body parts or kinship terms) and alienable (all other possessions) nouns. Alienable nouns are further divided into ingestible items (food and drink) and other nouns. This means that the phrases ‘my eye’, ‘my water (for drinking)’ and ‘my water (for bathing)’ are expressed by different constructions. Verbs in Ahamb can take prefixes for person (including inclusive and exclusive first-person nonsingular), number (singular, dual and plural), and a number of tense-aspect-modality markers. As in most other Oceanic languages, adjectives and numerals are structurally the same as verbs. Verb serialisation is common. What sets Ahamb apart from most other related languages is its relatively large vowels inventory and a set of two phonemic bilabial trill sounds (made with vibrations produced by the upper and lower lip), which are typologically very rare (Rangelov 2019). Another unusual feature of Ahamb is a set of special verbal markers that encode events occurring in sequence (Rangelov and Barbour 2020).

Ethics

This book engages with some sensitive material, and I would like to add these notes on ethics. The aim of the book is to present ethnographic material in a way that is as useful as possible to give insight into social phenomena, but without compromising the security and wellbeing of the participants in the study. To protect my interlocutors, I have used pseudonyms in almost all cases. As the ethnography deals to a significant extent with children, I have taken special care to make the visionary children unidentifiable by leaving out or changing details that could identify them. To give the reader a better impression of the startling revival events, I have included some photos in which visionary children appear. To protect their identities, I have in those cases blurred their

xx Notes on Text

faces and other distinguishing features. While anonymisation makes people unrecognisable for those not familiar with the person and place, some characters may inevitably be identifiable by people who know Ahamb well. However, I believe that it is the events themselves and not the individuals involved in them that will be of most interest for the reader. Since the tragic murder of the two men suspected of being sorcerers, I have discussed with their family members, Ahamb chiefs and other affected islanders to what extent I should include this incident in my writings. They have all encouraged me to write about the case to get their stories out. I thank my Ahamb friends and interlocutors, good colleagues, and representatives of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, the National Committee for Research in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), and the Vanuatu Cultural Centre for their help with the ethical decisions I have made in producing this book.

Chronology

•

The Revival Process

The Ahamb revival was a complex process consisting of many events, both small and large. In my attempt to understand the revival process, I include in the book what I consider to be significant happenings occurring during the period from 2009 to 2017. Here I present an overview of these happenings with the intention of making it easier to follow the revival process as I present it in the book: – June 2009: Lonour Island near Ahamb is leased to an expatriate. – 31 May 2010: The autochthonous leaders take over the Ahamb Council of Chiefs. – 30 October 2012: General election, in which the autochthonous leaders’ candidate for Member of Parliament (MP) loses to the nonautochthonous leaders’ candidate. – 16 June 2013: Father’s Day, when children performed ‘The Unity Song’ and skit. – November 2013: The revival breaks out in South West Bay, Malekula. – 5 March 2014: Initiation of the hae jif (high chief) on Ahamb. – 25 March 2014: Community forum meeting hosted by the Ahamb Council of Chiefs. – 28–29 March 2014: Revival introductory programme on Ahamb. – 23 May 2014: The first sorcery findings on Ahamb. – 5 June 2014: Lincoln gives away his sorcery herbs (lif). – 21 June 2014: The death of a four-year-old boy, Eliot. – 24 June 2014: Sorcery trial following the death of Eliot. – 14–19 September 2014: Revival convention for the Malekula Presbyterian Church in Farun village, during which Levi confesses to have killed Eliot and others by using sorcery. – 29 October–19 November 2014: Sorcery trial during which five men confess to having killed four people by sorcery. The trial ends with the two suspected sorcerers Orwell and Hantor being hanged.

xxii Chronology

– 22 January 2016: General election, during which Ahamb islanders reunite around a common MP. – February 2017: Reconciliation between an Eneton leader and the Ahamb community’s diaspora chief in Port Vila. – 6–10 November 2017: Community transformation on Ahamb, during which the great community reconciliation takes place on 9 November.

Map 0.1. Vanuatu in the Southwest Pacific. Map produced with the permission of CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University.

Map 0.2. Malekula, also spelled Malakula, in Vanuatu. Map produced with the permission of CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University.

Map 0.3. South Malekula with Ahamb Island in the centre. South West Bay, where the Malekula revival started, is to the left. Map by Tine Bratrud.

Figure 0.1. Phelix on mainland Malekula with Ahamb Island in the back. Photo by the author.

• Introduction Fear, Hope and Social Movements

The lively evening described in the preface was only one of many similar events that occurred during the revival, but it is not representative of normal everyday life on Ahamb. Ahamb islanders are mostly subsistence farmers and fishers whose daily lives rely on garden work on the hilly coastline of mainland Malekula. Here, people grow various root crops, breadfruit, bananas, fruits and leafy greens for food, while kava and to some extent coconuts for copra serve as cash crops used to pay school fees and the occasional cargo ship ticket to the capital, Port Vila. In addition to garden work and some fishing or shell collecting, daily life on the island typically includes spending time with kin, planning and carrying out little projects in one’s home or for relatives, and attending meetings in church and in community committees. Most Ahamb islanders live on Ahamb itself, and these count about 600. But since the late 1990s, a number of families – currently counting about 250 persons – have migrated to about a dozen new settlements on the Malekula mainland due to lack of space, land disputes, to stay closer to the gardens or to escape the environmental vulnerability of the small, flat island. About 100 islanders also live permanently or temporarily in Port Vila. The research for this book is based on a total of twenty months of fieldwork among Ahamb people – mostly on the island proper, but also among Ahamb families on the mainland and in Port Vila in 2010, 2014–15 and 2017.1 Contemporary Ahamb society consists of a mix of patrilineal clan groups who trace their origins to the island itself and to previous settlements on mainland Malekula. The clans were brought together by conversion processes of the Presbyterian Church starting in the late 1800s, and the present-day Ahamb community, composed of kin groups from various places in South Malekula, was formed in this process. Ahamb people are proud of their Christian history and how it is materialised in their community and way of being: the Ahamb community has a primary school, dispensary, committees for just about any activity, and a thriving congregation, which all came about with the formation of the Presbyterian community church. Like many other societies throughout the Pacific, Ahamb people also take great pride in living up to moral values of love and care that are based in the reciprocal duties of kinship, but have

2

Fire on the Island

been reinforced and magnified with Christianity – a religion that emphasises compassion for others (see Brison 2007; Hollan and Throop 2011; McDougall 2016; Robbins 2004a). The values of kinship and Christianity converge in islanders’ ideas and practice of ‘the Ahamb community’ (komuniti blong Ahamb). For Ahamb people, ‘the community’ refers to a togetherness in kinship, in the Church and in the discrete island being just big enough, and far enough away from surrounding villages, to form a cohesive society. As anthropologists have been careful to point out, the term ‘community’ can be problematic if it evokes functionalist or organic images of a bounded entity (Amit and Rapport 2002: 42). Like every other society, Ahamb is not a circumscribed social entity, and there are fractures and contradictions among its inhabitants, as I will show in this book. But the term and idea of ‘community’ is something that the people themselves are passionately concerned about and something they are constantly seeking to achieve. We can therefore say that, for Ahamb people, community is often the goal, if not the ground, of social life (see also Eriksen 2008; Lindstrom 2011; McDougall 2016; Rasmussen 2015). However, over the past two decades, the island has become particularly rife with disputes over land rights, leadership and questions about who should be eligible to live on the small island, particularly as space and resources are diminishing. The disputes have led to a persisting division in the community, which for many islanders is synonymous with failure to achieve good moral living. The divisions have sometimes led to a breakdown of vital community institutions, including the health committee that runs the dispensary, because committee members have been on different sides in disputes. Divisions have also kept people from participating in communal work and church activities. Moreover, there is a constant fear that disputes and rivalry could lead to sorcery activity whereby someone might hurt their opponent or their opponent’s family in surprising and incomprehensible ways. The divisions and sorcery fears make people anxious about visiting kin in other villages as freely as they would like and about participating in larger ceremonies that attract many people. The context of dispute and division is thus making it harder to realise what most islanders find to be the ideal way of living, which revolves around living together as a unified community of Christian kin. This ideal even seemed impossible – that is, until the revival arrived, offering a framework for transforming society’s maleficent elements into sacred beneficence. In 2014, during my second period of fieldwork, Ahamb became the scene of a startling Christian charismatic revival, which upended many aspects of social life on the island. The discourse of the revival was that ‘all of us must change’ (yumi evriwan mas jenis) and the direction was set by visionary children through messages and visions from the Holy Spirit. At this point, many islanders were longing for a radical change in society because of the disputes,

Introduction

3

divisions and spiritual insecurity related to sorcery fears. The revival became a collective therapy led by the Holy Spirit to move away from division and insecurity and into ‘the true will of God’ (stret rod blong God), which was a path of humility, reverence and unity. It resembled a collective sacrifice – in René Girard’s words (2013), ‘digesting’ society’s bad immanence so that it could be reborn in a new or renewed form. While the revival was a phenomenon that reached many Presbyterian villages in Malekula in 2014–15, it was regarded as having been particularly strong on Ahamb. The overarching argument of this book is that in contexts of insecurity and upheaval, fear and hope are powerful sentiments that work together to become a potent driving force for change. My argument is influenced by philosopher René Descartes, who – in his last published writing, The Passions of the Soul, completed in 1649 – proposes the complementarity of fear and hope, two feelings that are often seen as contradictory: Of hope and fear. Hope is a disposition of the soul to persuade itself that what it desires will come to pass . . . And fear is another disposition of the soul, which persuades it that the thing will not come to pass. And it is to be noted that, although these two passions are contrary, one may nonetheless have them both together . . . When hope is so strong that it altogether drives out fear, its nature changes and it becomes complacency or confidence. And when we are certain that what we desire will come to pass, even though we go on wanting it to come to pass, we nonetheless cease to be agitated by the passion of desire which caused us to look forward to the outcome with anxiety. Likewise, when fear is so extreme that it leaves no room at all for hope, it is transformed into despair; and this despair, representing the thing as impossible, extinguishes desire altogether, for desire bears only on possible things. (Descartes 2015: 264) Put simply, an excess of fear drives out hope and leaves us paralysed, without the capability of acting for change. Similarly, an excess of hope drives out uncertainty and makes us too confident that things will turn out for the good; therefore, there is no need to act for change at all. But fear and hope combined becomes a generator for change: if we fear that something bad may happen, but also hope we can avoid it, we usually work for the good to happen rather than the bad. Similarly, if we hope that something good may happen, but fear that it will not, we are motivated to act for the good to happen instead of the bad. I argue that the stronger the fear and hope, the higher the possibility that people will seek ritual events like the revival that allow them to ‘break free from the constraints or determinations of everyday life’ to possibly alter, change or transform them (Kapferer 2006b: 673). As Bruce Kapferer maintains, rituals imply a notion of temporary autonomy from one’s surround-

4

Fire on the Island

ings and can therefore become generative centres for creativity and change in which outcomes are relatively open and not confined to the limits of the current everyday world (Kapferer 2005: 46–49). Kapferer’s view resonates with that of Erika Summers-Effler (2002), who points out the importance of rituals in driving social movements forward. Drawing on Durkheim’s (2008) ideas of collective effervescence – that is, the extraordinary energy created when individuals come together in the same thoughts and participate in the same action – Summers-Effler argues that the moral solidarity generated by ongoing or repeated ritual is crucial for social movements because these depend so highly on the emotional energy of hope. Ritual experiences of solidarity and progress are necessary for social movements, she contends, because they have the power to transform participants’ feelings of depression, anger and shame into feelings of hope. It is this hope that generates participants’ willingness to take risks on behalf of the movement in order to work for creating change (Summers-Effler 2002: 54–55). However, because of the potential openness of rituals, they can also become an unpredictable space that generates a range of different unintended outcomes. As shown at several points in this book, rituals meant to drive participants in a certain direction towards certain goals may easily lead to new risk, uncertainty and problems. I argue that this is because although followers agree on the movement’s ideological project, they may have different desires, interests and interpretations, which are revealed when the movement’s ideas are turned into practice as it moves along. Attempts of participants to resolve such ambiguities will eventually feed back into the dynamics and practice of the movement and affect its forms, meanings and outcomes in ways that can be as disturbing as they are ordering. Pertinent to the Ahamb revival, Ernesto Laclau (2018) claims that those who unite in popular political movements often do so because of a shared frustration with current authorities and the status quo. The movement’s adherents are constituted as ‘the people’, which appear as a unified political force of opposition. However, Laclau argues that such movements are normally fragile constructs. The unity of the group is often based on participants identifying with one another by and through their common opposition to something or somebody. But this does not mean that the unity of the group is secured by common desires and demands. In reality, the demands of the followers are numerous and heterogeneous, and often even incompatible (see also Bennett 2012: 19). The movement itself, its rituals or its images – which have come to represent the totality of unsatisfied social demands – thus become an empty signifier. It merely points to a lack, an absent social fullness – a longed-for but unrealised possibility (Laclau 2018: 85). The revival on Ahamb shares many features with the movements characterised by Laclau. The revival was born out of experiences of lack and re-

Introduction

5

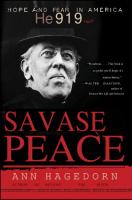

Figure 0.2. The revival was a deeply affective ritual process. In this photo from December 2014, the women and children sitting on the floor are just waking up, allegedly after being struck by the powers of the Holy Spirit during a revival event in the Ahamb Presbyterian community church. Photo by the author.

sentment, and it was also fragile, in that participants proved to have different interests and stakes that, in the end, did not ‘correspond to a stable and positive configuration which could be grasped as a unified whole’ (Laclau 2018: iv). However, I argue that the revival was not only based on empty signifiers; it was motivated by largely shared notions of what constitutes a good and bad social world, and largely shared hopes of realising people’s ideas of the former and escaping their fears of the latter.

Fear, Hope and the Good

When I speak of fear and hope in this book, I explore, in the deepest sense, how Ahamb people and others strive to create what they think of as good in their lives. When I say ‘good’ here, I refer to Joel Robbins’ use of the term as what people take to be desirable, all things considered (2013a). This book is thus part of the emerging field of the ‘anthropology of the good’, as articulated by Robbins and others (e.g. Fischer 2014; Haynes 2017; Knauft 2019; Malkki 2015; Ortner 2016; Venkatesan 2015; Walker and Kavedžija 2017). This field includes studies of value, morality, imagination, wellbeing, empathy and hope –

6

Fire on the Island

topics that foreground possibility and develop new models of temporality and social change. However, while studies of ‘the good’ enrich our understanding of how people strive for change and betterment crossculturally, there is a comparative lack of research situating fear, anxiety and violence within processes of constructing the good.2 By incorporating a focus on fear and crisis with recuperation and hope, I address in this book less-examined questions of the place of negative emotions in an attempt to fulfil positive visions of the future. While the anthropology of hope has had a ‘boom’ (Kleist and Jansen 2016: 373) at the start of the third millennium (see e.g. Appadurai 2013; Cox 2018; Crapanzano 2003; Kleist and Thorsen 2016; Miyazaki 2004; Pedersen 2012; Srinivas 2018), fear has not received much explicit attention in the discipline, although most studies of violence, conflict and oppression may be said to be about fear in one way or another.3 In my approach to fear, I find Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pedersen’s efforts to couple feelings of fear and danger with (in)security useful. In their book Times of Security (2013), they insist on acknowledging that (in)security means different things to different people. This acknowledgement resonates with Robbins’ (2013a) reminder that different people have very different senses of what constitutes a good life. Similarly, people also have different perceptions of how their notions of a good life might be threatened. By combining ideas of the good (including hope) and of insecurity (including fear), I aim at an approach that is sensitive to the potentially multifaceted stakes people have in their everyday lives, which emphasises in(security) as culturally, socially, historically and situationally variable. The revival on Ahamb was a movement but also a startling ritual context and event that for the time being turned life on the island upside down. In this book, I build on Kapferer’s work and argue that rituals and events can give us particular insights into how new sociocultural realities are formed. To paraphrase Kapferer, the revival entailed a radical suspension of ordinary everyday life and offered a generative moment of innovative practice that reconfigured some existential and social structural matters in society. This realisation of new and as-yet unrealised possibility is typical for the uniqueness and creative potential inherent in rituals and events (Kapferer 2005, 2006b, 2015a). However, as both Kapferer (2015a: 18) and fellow event-theorists Marshall Sahlins (1980, 1985, 2005) and Michael Jackson (2005) argue, events first obtain their importance and effects through the meaning and significance that people attach to them. As shown in this book, the revival entailed battles over life and death, which are essential themes to most people. But I also suggest that the revival became so important because it addressed and actualised some of the most vital social values of Ahamb society – values that people hoped to realise and feared they would lose. In this way, we can see the revival as both ‘cultural’, as it draws on the past and the present, and going ‘beyond culture’, by virtue of realising potentials in a future that did not yet exist (see Robbins 2016: 707).

Introduction

7

From being a relatively understudied theme in anthropology, at least in an explicit and focused sense,4 the anthropology of morality, values, and ethics has recently been rapidly expanding. Signe Howell’s edited book The Ethnography of Moralities (1997a) became something of a landmark for a new generation of anthropological enquiries focused on values, morals and ethics. Howell’s volume was the first to acknowledge explicitly not only the centrality but also the complexity of these themes, stressing that societies are composed of a variety of moralities rather than one all-encompassing moral order. It also established an approach to morality and value that takes them as dynamic processes in which individuals are reinterpreting moralities, instead of simply conforming to a moral order. Several influential books, edited collections and special issues have emerged since then, all offering perspectives on how to understand and analyse morality, moral values and ethics in everyday lived experience (e.g. Fassin 2012; Faubion 2011; Heintz 2009; Hollan and Throop 2011; Kapferer and Gold 2018; Keane 2015; Laidlaw 2014; Lambek 2015; Otto and Willerslev 2013; Robbins 2004a; Sykes 2009; Zigon 2008). The following chapters explore different moral discourses operating on Ahamb. Each of the moralities is predicated upon a specific kind of sociality (such as male and female, lineage and community) and is made operational by different people according to context (such as in peace or dispute) (see Howell 1997b: 5, 11). I agree with Howell (1997a), Martin (2013), Robbins (2013b), Toren (1999b) and others on the importance of acknowledging that in any social milieu and social situation, a variety of moralities and equally important and antithetical values are at play. It is only reasonable to assume that differently positioned people, with different social and emotional experiences, would have different perspectives on morality and the good in different contexts. However, if everyone would impose his or her own unique set of values on the world, social life would be an even more chaotic place than it already is. This, Robbins (2015a) argues, is where culture comes in and where values, an intrinsic part of culture, offer ideas that motivate action and can create a relatively orderly world because certain values are shared between members of a society. However, because everyday life involves many different concerns, it is first in the social form of the ritual that these values are expressed in their ‘fullest form’ (Robbins 2015a: 21). From the outset, the revival appeared as a ritual that promised the realisation of the local value of love (napalongin or lav, comprising care, peace and unity) in its fullest form. I argue that the movement largely amassed the force it did because people were hoping to reinstate the central place of this value in society while simultaneously fearing it was going to get lost. But the revival was also constantly an ambiguous site for evaluating what values should entail in practice, the clearest example being that a murder was committed in the name of love by people who normally insist that murder is the most explicit

8

Fire on the Island

antithesis of love. This illustrates how even religious values, which constitute the ultimate value spheres of society for value-theorists Louis Dumont (1980) and Talcott Parsons (1935), may become ambiguous when put into practice (see also Bratrud 2021a).

Grasping Social Movements in the Making

This book seeks to understand the ways in which the intersection of fear and hope may drive novel sociopolitical movements. However, as my ethnographic material of the revival and other accounts demonstrate, such movements often run the risk of exacerbating the very problems they seek to address. To grasp this complexity, I am inspired by the classic extended case study, or situational analysis, developed by Max Gluckman (1958[1940]) and the so-called Manchester School of Social Anthropology (see also Evens and Handelman 2016; Mitchell 1983). In a situational analysis, the researcher focuses on the ongoing process of social life, which is often complex and full of contradictions. By examining in detail situations of breaks and conflicts, the researcher seeks to identify the mechanisms underlying the development of these breaks and conflicts, which can then reveal the social and political tensions at the core of everyday living. The goal is then to develop theoretical insights from the ongoing process of social life rather than from selected illustrations of it. Victor Turner’s influential argument about the potential for change during liminality in ritual, and the universal dialectic relationship between structure and anti-structure, are examples of this approach (see Turner 1974: 272–93; 2008 [1969]). To utilise the potential of this method to identify the driving forces of social movements, in this book I give more prominence to the place of social values, ontological assumptions and future visions than has previously been done by scholars of this methodological perspective. An important aim of this book is to say something about contemporary sociocultural life on Ahamb by examining the revival. Here, I lean on Turner, who argues, following Sigmund Freud, that studying disturbances of the normal and regular often gives us greater insight into the normal than can be gained by direct study of it (1974: 34). Events, as an instance of liminality or anti-structure, ignore, reverse or cut across the normative order and may in this sense put the normative order into relief. Michel Foucault (1991) has a similar view, arguing that what we call events only reveal more dramatically that which is already simmering under the surface of things. Turner’s and Foucault’s views allow us to say more about the power dynamics at play that may hinder certain issues of conflict from emerging in the structures of everyday life, but may be expressed in the event. I suggest that this approach is particularly relevant when assessing how Ahamb women and youth, who normally lack a public arena in which

Introduction

9

they can speak to the male leaders of the community, could use the revival as a stage for expressing their criticism of community leaders. Radical Christian revival movements have also been the subject of previous studies. The most well known is Joel Robbins’ seminal book Becoming Sinners (2004a), which analyses the social changes brought about by a Christian charismatic revival movement among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea in the 1970s. Other scholars have also examined the radical force of such movements that occurred in several places in Melanesia in the 1970s (Barr 1983; Burt 1994; Flannery 1983; Griffiths 1977; MacDonald 2019; Robin 1982; Tuzin 1997). The revival movements, sparked by new mission campaigns coinciding with the growth of political independence movements, can be seen as successors of the classic Melanesian social movements, often referred to as ‘cargo cults’, which have been widely discussed in the literature (e.g. Burridge 1960; Jebens 2004; Lawrence 1964; Lindstrom 1993; Otto 2009; Schwartz 1962; Tabani and Abong 2013; Worsley 1957). Underlying the ‘cargo cults’ was also desire for radical change – or, as Peter Lawrence puts it, the goal of ‘completely renewing the world order’ (1964: 222). But their ultimate aim, Lamont Lindstrom (2011) argues, was to create new unity among people who were variously oriented or divided. This desire, which I will discuss in Chapter 2, is rooted in the cultural notion that failure to achieve social cohesion not only threatens the social order, but also threatens the very constitution of persons themselves. Achieving unity therefore becomes an existential matter in relation to which many Melanesians direct considerable amounts of energy. From this perspective, the Ahamb revival is part of a continuum of social movements in Melanesia aimed at breaking free of a disintegrated problematic present by reimagining and changing it through ritual and religious means (see MacDonald 2019: 400). Since the 1970s, these attempts have mostly taken place within the Pentecostal-Christian charismatic framework, which promises a ‘break with the past’ (e.g. Eriksen 2009a, 2009b; Eves 2010; Jorgensen 2005; Robbins 2004a), but also through neotraditional nativistic movements, new political parties and other social innovations (see Hviding and Rio 2011; Lindstrom 2011; Schwartz and Smith 2021; Tabani and Abong 2013).

Doing Research on the Revival

Impactful charismatic revivals do not occur that often, and previous studies have been based on fieldwork carried out in their aftermath. Accounts of them are thus necessarily based on oral accounts and archival material. However, the study of this book is based on my full embeddedness in a revival community during the course of its advent and growth until its demise. This has allowed me to study the phenomenon in its broader context as well as from

10

Fire on the Island

its centre, which has been both a rewarding and a difficult task. The revival was an event that brought surprise, wonder, hope and fear to most people on Ahamb, including myself as the ethnographer. I admit that I had many experiences that could not be easily represented based on my previous logic and anthropological toolkit. Martin Holbraad (2012) argues that ethnographically driven aporia – the state of puzzlement – is important for anthropologists as a condition for gaining new insights. Whenever an experience of alterity causes an anthropologist to marvel, Holbraad argues, one should resist the inclination to explain that alterity away as indicative of ignorance, metaphor or madness. Instead, we should allow this alterity to generate new insights that might destabilise what we think we know (see also Scott 2016: 478). I have followed Holbraad’s advice in this book and avoided quick conclusions and explanations to incidents that I could not readily understand. Instead, I have aimed at providing sufficiently detailed ethnography to make the event ‘speak for itself ’ and let the participants’ explanations come more to the foreground than my own attempts at understanding. In this way, I also try to avoid the habit that many anthropologists have, according to Roy Wagner, of confusing the ways in which we study phenomena, and the theories through which we understand them, with the phenomena themselves. Wagner says: ‘We talk about the world (quite understandably) in the ways we have come to know about it . . . conclusions are to a certain degree pre-determined’ (1974: 119). By using our own models of the world when trying to understand others, we are creators of the culture we believe we are studying no less than the people we study (1974: 120; see also Wagner 1981: 4, 12). In this book, I focus primarily on my interlocutors’ experiences during the revival and what the implications were, but I also include some of my own experiences to show how I was not left untouched myself. It became clear to me early on that I could not study the revival properly without taking part in the situations in which it manifested itself. To come as close as I could to understanding what the revival signified for different people, I allowed myself to be caught up in the events, observing and participating in prayer sessions of healing and the neutralisation of sorcery, including sessions to pray against and neutralise sorcery that was aimed at myself. Like many others in Malekula, I was granted spiritual gifts during the revival that gave me access to special prayer meetings and consultations.5 I think this gave me some access to the revival discourse and allowed me to join a fellowship with other community members who were caught up in it, like myself, both voluntarily and involuntarily (see Favret-Saada 1980: 15; Goulet 1994: 20). As a result, when talking with Ahamb people about the events, they still tell me: ‘You understand because you have experienced it.’ I should note here that even though I have not had a particularly religious upbringing and have

Introduction

11

not participated in much organised religious activity, I have always believed in what I call ‘God’ in some form. Therefore, it was not so difficult for me to accept the transcendentality of the revival itself, even though some parts of it were very difficult to deal with and went far beyond my own register.

Outline of the Book

The title of this book, Fire on the Island,6 points to three themes in the book. First, it refers to the ‘overheated’ (Eriksen 2016) sociopolitical turbulence in which the revival emerged and that it was meant to overcome. Second, it reflects how the revival itself became an overheated site of hope and fear with unintended consequences. Third, it refers to how the Holy Spirit was described to burn ‘like a fire’ by the visionaries, who often conveyed that there was fire on the ground where healing sessions took place, and fire on the heads of people who were anointed with the Holy Spirit. The image of the Holy Spirit as fire is well known from the Bible. At Pentecost, for instance, which marks the coming of the Holy Spirit to dwell in Christian believers, the Bible says that tongues as of fire appeared over the heads of each of those who gathered together (Acts 2:3).7 The revival came to Ahamb as a fire, but also appeared before the visionaries as a windstorm, a white cloud, a thick fog and rain. Common for these forms was that they penetrated everything in sight. And, as out of a bush fire and nourishing rain, new things would grow. I start in Chapter 1 with a prominent climax in the revival – that is, the lynching of two men who were feared to be sorcerers and responsible for most of society’s problems. This happened nine months into the revival and after five months of ‘spiritual war’ with numerous sorcerers. I approach this event as an existential panic in which extraordinary collective action is needed to counter perceived threats to society’s wellbeing. I discuss the murder as a sacrifice, in Girard’s terms, when during a period of crisis, a victim takes the blame for all accumulated fear, anxiety and violence in the community. The victim is taken down – sacrificed – in order to purify the community from its problems and allow a new start. However, when the panic subsided and the implications of the act became clear, it was evident that the two men, who were family and community members, were not legitimate victims of sacrifice after all. This chapter sets the stage for my unpacking of the revival process in the succeeding chapters. Chapter 2 offers a background for understanding how the revival constituted a religious-political platform from which all kinds of social problems were addressed and attempts were made to solve them. I outline one of Ahamb people’s core social values, often summed up as love, and how it is rooted in two main domains that shape and inform choice and practice on the island

12

Fire on the Island

today: kinship, with its duties and obligations of sharing and reciprocity, and Christianity, reflected in Jesus’ commandment to humankind that everyone shall love one’s neighbour as one loves oneself. I go on to discuss how disputes over land rights, triggered by postcolonial land reforms and a subsequent turning of custom land into tourism real estate, threaten Ahamb people’s realisation of these values. As a result, many islanders felt their society to be morally adrift, which made them long for new means and sources of power to deal with these challenges. Chapter 3 discusses the revival’s beginnings. As background, I explain how specific conflicts in the two years before the revival made community leaders try different strategies for changing society, although without success. People were resigned and angry about how division and leaders’ inability to create change led society into spiralling decay. I argue that the revival, which was introduced by visiting ‘born again’ youth with spiritual gifts, offered a new and different space in which the problems of society could be articulated. Already in the revival’s first week, local children and youth received spiritual gifts and visions from the Holy Spirit and made chiefs reconcile longstanding disputes in public. Many islanders experienced these reconciliations as miracles, which mobilised them around the visionary children and the revival. Building on the theoretical work of Robbins, Kapferer and Sahlins on values and events, I discuss how fear of losing important values, in combination with new hope that they may nevertheless be fulfilled, are key to understanding the mobilising power of stand-out events. Chapter 4 shows how mobilisation around shared values, hopes and fears does not necessarily create order. Drawing on ethnography of the revival’s first two months, I show how the social values promoted in the revival were ambiguous because differently positioned people interpreted unfolding events in diverse ways and expected conflicting kinds of appropriate action. I focus particularly on how the revival banned the popular intoxicating drink kava, which normally plays an important role in the everyday social life of men. For the men, the revival, which was a hopeful project based in fear and insecurity, was thus generative of new insecurity and risk. Further, I show how the revival ritually inverted gender- and age-based hierarchies on Ahamb because little children became society’s new leaders, and male chiefs and leaders were blamed for most of society’s problems. I discuss how this inversion created challenging ambiguities that had to be negotiated by the community. Chapter 5 presents the revival’s most intense periods of fear but also of hope. I describe how the revival’s importance exploded in May 2014 when a ‘spiritual war’ between Ahamb’s Christians and invisible sorcerers broke out. The visionary children started detecting sorcery objects on the island and identifying their owners – knowledge that is normally secret. The spiritual war engaged people intensely: everyone in the community, including myself,

Introduction

13

was caught up in daily sessions to stop the influence of sorcery. I discuss how through the perceived availability of the Holy Spirit, who ‘sees everything’, the revival, like other charismatic-Pentecostal movements, offers a space through which harmful forces can be targeted. However, by articulating and targeting evil forces, their activities may also generate new experiences of risk, fear and insecurity as much as they offer relief from them. I therefore argue that in the Ahamb revival, as well as other movements that localise forces believed to be responsible for one’s misfortune, the cultivation of fear and hope as opposing forces may result in the two reinforcing rather than counteracting each other. Chapter 6 discusses the conflicts that emerged in the wake of the killing. These conflicts demonstrate that even though people mobilise around the same fears (e.g. sorcery) and hope (e.g. that sorcery can be evicted), they may not agree on the appropriate action to handle their shared fear and hope. However, common values, social obligations and political interests may bring people in crisis together in new ways. The chapter thus illustrates how shared ideas and values do not necessarily lead to uniform practice, yet senses of crisis can still create new common ground in surprising ways. The ethnographic focus of the chapter is the first six weeks after the killings (when I was still in the field), the next three years of negotiation about their meaning, and the circumstances around a major reconciliation ceremony organised in November 2017 during my third period of fieldwork on Ahamb. Chapter 7 draws together the ethnography of the previous chapters and argues that senses of fear and hope mutually constitute people’s strategies for managing complex contexts of insecurity and social change. I begin by discussing how the children, who from certain perspectives are the lowest in Ahamb’s social hierarchy, could amass the support and force they did. I go on to compare the Ahamb revival with similar renewal movements elsewhere where people have perceived their values and order to be under threat, which mobilised them in hope of change. Common to these movements, I argue, is that in contexts of insecurity, when people feel powerless and out of control of their lives, locating the source of misfortune in morally deviant persons or groups offers relief and hope for betterment and change. The blaming is often amplified by new charismatic actors of governance who present themselves, or are presented, as the solution to the crisis. An important part of the appeal of these actors is that they appear to take people’s concerns seriously in a way that established authorities do not. In contexts of uncertainty, they become an alternative, good ‘other’ to mobilise around, which symbolises a radical break with the problematic past. I make comparisons between the hope associated with Ahamb’s visionary children and the role of similar figures elsewhere, including Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, who, like the Ahamb children, shows no regard for established hierarchies and has mobilised hundreds of thousands of climate activists demanding radical change. I also make com-

14

Fire on the Island