Equity Stirring: The Story of Justice Beyond Law 9781474200646, 9781841138466

Sir Frederick Pollock wrote that ‘English-speaking lawyers … have specialised the name of Equity’. It is typical for leg

245 58 2MB

English Pages [280] Year 2009

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 5 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

To my grandparents, John and Lil Wright, With love.

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 3 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 6 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 4 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 7 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Author’s Preface

Before I begin, I will take this opportunity to say a few words about my choice of titles and topics. I start with titles, because one of the aims of this book is to explore the potential of a cultural discourse, based on equity, to resist a culture of entitlement, based on rights. The inscription of title and entitlement by a process of formal abstraction is one of the founding exercises of the law, but the process is fundamentally erroneous and calls for equity’s correction, since a mere title can never express the whole truth. I chose the title Equity Stirring for a number of reasons which will become apparent throughout the course of the book, but mainly because it expresses equity’s active and unsettling influence over the conventional and complacent. To the extent that this book is a book about resistance to entitlement, it might be thought that it needs no title – or even that it needs to have no title. That would be to misunderstand the sort of resistance that equity offers. Equity is not revolutionary – it does not seek to do away with titles and other formal abstractions. On the contrary, equity exists only because titles and other formal abstractions are necessary and are necessarily flawed. Equity does not ignore the track set out by abstraction and the route established by routine – it tries to follow the formal path as far as possible, but it will depart in those places where the path deviates too far from the natural terrain and the topography of what is humane. Equity is not a sentient being, however potently we personify it, but it is a human art to judge when and to what extent it is desirable and possible to depart from the right road without leaving it utterly. So the sub-title to this book, The Story of Justice Beyond Law, indicates that equity engages with the regular law, but with a concern for something more than the regular law. The sub-title also indicates that this is the study of a story; it is a cultural, linguistic and literary history of an ancient and universal feature of human engagement with regulation and routine. It is not an empirical or doctrinal analysis (although I hope to add something to our doctrinal understanding of legal equity, and to say something about the limits of the empirical and doctrinal in the field of law); it is, rather, a study of the idea of equity across many fields of the arts and humanities, and a study of the common law idea of equity from the perspective of the arts and humanities. It is, especially, a study of

vii

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 1 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 8 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Author’s Preface equity by the lights of the literary arts, and in that sense this book belongs to a growing body of work devoted to the study of ‘law and literature’, within the broader field of ‘law and humanities’. I will now outline the topics addressed in the chapters of the book. The book has seven chapters. The first, entitled ‘Excursion’, encourages us to step outside our usual courses. It is concerned with education in the true etymological sense of the word, in that it aims to conduct readers out of their familiar disciplinary domains and into a discourse between the disciplines. The need for engagement between the humanities’ disciplines is especially pressing in legal scholarship and legal practice, since the law, according to its origins and obligations, should be a prime locus for humanities’ scholarship and the humane arts but is nowadays to a great extent alienated from them. I demonstrate that there is an interdisciplinary consensus regarding the virtue of equity and that equity can be seen, as Aristotle saw it, as a feature of good character. I identify various qualities of equity to which we may aspire – not in the pursuit of any moral ideal – but in order to avoid the harm inherent in the worst extremes of formalism, legalism, regulation and unthinking routine. In summary, then, the opening chapter encourages us to read beyond the literature of the law and to read beyond the letter of the law. Chapter two, entitled ‘In Chancery’, explains the historical processes by which the English Court of Chancery came into being, and how the concept of equity – and especially Aristotelian and Christian versions of the concept – came to be confined within it. In this chapter we discover that chancery is synonymous with incarceration as a matter of historical fact, as a matter of etymology and as a matter of concern in the literary works of authors including Carlyle and Dickens – it is through these discoveries that this chapter offers a new explanation for Dickens’ choice of Jarndyce and Jarndyce to be the name of the terrible chancery case in his novel Bleak House. Another incidental discovery is a possible connection between Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure and the order made in 1616 by which King James I confirmed the jurisdictional supremacy of the Court of Chancery over the courts of common law. The other major theme of chapter two, in addition to the theme of chancery and incarceration, is the theme of chancery and violence. I do not say so in the text, but this theme leads into the title of chapter three, which is ‘Chancery Script’ – the formal connection lying in the fact that the chancery was originally a department of scribes and to inscribe is literally to scar. The substantial object of chapter three is to survey the technical language developed in the Court of Chancery – drawing out the various lines through which the legal idea of equity has been expressed and within which it has been contained and constrained – with a view to ascertaining whether the language of equity developed in chancery still expresses any of the virtues inherent in the original. I conclude that the essential virtue of equity, which is to moderate the worst excesses of legalism and formality, can still be seen within the maxims, doctrines, remedies and proprietary creatures of the Court of Chancery. The middle chapter, chapter four, is the conceptual heart of the study because it argues that equity’s operation in relation to general law parallels the operation of viii

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 2 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 9 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Author’s Preface metaphor and other poetic tropes in relation to prose. It argues, in short, that different aspects of law correspond to different aspects of literature. This chapter, which is entitled ‘Figuring Equity’, argues that to understand or ‘figure’ equity, one has to resort to figurative language because equity functions as metaphor functions. Metaphor expresses abstractions in terms that are concrete and tangible, and equity humanises legal abstractions by connecting them to the matter at hand. Chapter four proceeds to assess the relative merits of the many metaphors that are used to describe equity’s operation in law; casting doubt on some of the most popular metaphors, including the metaphor of the scales, and offering more nuanced, including some new, metaphors in their place. That chapter concludes with a brief introduction to the personification trope, which leads directly to chapter five, ‘The Equity of Esther Summerson’. In this chapter, I argue that the heroine of Dickens’ Bleak House is the perfect literary personification of equity, because she moderates the contrary extremes of stasis on the one side and displacement and destitution on the other – stirring those who are still and settling those who are disturbed. (‘Stasis’ is a word with a wide range of meanings, some of which conflict, but I use it throughout this book to denote a stubbornly unmoving state.) Dickens and Shakespeare are the writers most often referred to throughout this study, and chapter five, with its focus on Dickens’ Bleak House, leads to chapter six, on ‘Shakespeare’s Equity’. I am aware that there might appear to be a certain irony in the fact that my search for the virtue of departing from norms has taken me to two of the most enduringly popular writers in the mainstream literary canon. There are a number of reasons for the choice. The first is the contingency of my own taste – these happen to be writers whose work I enjoy and know quite well and desire to know better. The second is that I have written this book for an interdisciplinary readership, so it makes some sense to meet on common ground which is familiar enough and large enough to attract and accommodate readers approaching the book from a diversity of disciplinary backgrounds. The third reason is that the works of Dickens and Shakespeare engage deeply with the law and with the problems inherent in legal systems and strict legalism. This may be down to the fact that they both had significant personal encounters with the law and lawyers and the pains of litigation. Dickens even worked as a lawyer’s clerk and Shakespeare worked with a law-writer and might even have worked as one himself. However, it is not their technical familiarity with the law that makes them so valuable to the present study. It is the fact that Dickens produced equitable characters like Esther Summerson who do not judge the law harshly, but nudge it from harm’s way; and it is the fact that Shakespeare’s works – especially his dramatic works – are in various senses equitable. Like all drama, Shakespeare’s plays offer a scripted text to be adapted to particular performance by humane arts of interpretation – which mirrors the equitable performance of the texts of law. Like the best drama, they achieve a deep connection with the audience through the portrayal of fundamental tensions in human nature and the schemes of social life and they maintain the drama by refusing to pass definitive judgment on the conflicts that ix

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 3 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 10 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Author’s Preface are portrayed. To maintain tension between extremes is equity’s constant activity – it is, to use Shakespeare’s own language, ‘equity stirring’. The final chapter carries the title ‘Pretence of Equity’. It summarises the story of equity as it is told throughout the book and considers how the story might extend forward, beyond the book, and what part we might have in telling it. The title to that final chapter is also an acknowledgement that there is inevitably an element of pretence in every work of interdisciplinary scholarship. I put this book forward as an interdisciplinary engagement with equity, but I do not pretend to know as much about literary scholarship, or classics, or theatre, or any of the other disciplines I appeal to, as I profess to know about the law. To use lawyer’s language (or is it liturgical language), I hope that I will be forgiven my trespasses into neighbouring fields of scholarship. One respect in which my alien status might be apparent to literary scholars is in my willingness to refer to the writing of literary critics and commentators who might nowadays be considered old-fashioned, just as I have also favoured many legal theorists who were also in their prime around the limits of living memory. The fact is that equity is a truly archetypal idea, having its earliest expression in the written remnants of the oral tradition of ancient civilisations, and some of the clearest and strongest statements on equity have been made by scholars whose methods and attitudes have for other intents and purposes fallen out of favour. Where I have found my sense of equity expressed clearly by other writers I have been happy to approve that aspect of their work without judging their work as a whole and without judging them personally. I hope that this is an equitable way to read the writers of the past. It remains to thank my wife Emma and my sons Jamie and Michael for bearing with me – again; and to offer my thanks to the very many colleagues and students who have encouraged me in the study of law and humanities and joined me in it. For their general enthusiasm and their willingness to make an excursion from the typical course of a law degree, my first thanks must go to the adventurous students who opt for my course on law and literature. This is also a place to express ongoing appreciation for Paul Raffield, who is my co-worker towards a more humane legal education as well as being my fellow general editor of the journal Law and Humanities. That journal, like this book, is published by Hart Publishing and I owe a great debt of gratitude to the hard work and vision of Richard Hart and his team, and to the anonymous reviewers of this book. It is Richard’s ability to see beyond the routines of legal scholarship that has established the excellent reputation of Hart Publishing and long may it thrive. Daniela Carpi is another friend and colleague who deserves special thanks. Many of the ideas appearing in this book were developed in papers that I first delivered at conferences hosted by her in the beautiful city of Verona. I am grateful to the contributors to those conferences who have helped refine my own thinking, many of whom are referred to throughout this book. I am also grateful to the organisers of, and contributors to, a conference held in 2007 at the University of x

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 4 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 11 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Author’s Preface Cambridge under the title ‘Beyond Reasonable Doubt’. Elements of the concluding chapter of this book were first presented there. Particular thanks must go to those who have been kind enough to read over one or more of the chapters of this book at various stages of its development. They have, without exception, removed errors and added new insights. I am grateful to James Harrison for reading chapters one and three, and to Panu Minkkinen for his observations on chapter one; I am grateful to John Snape for reading chapter three, to Simon Gathercole for his observations on chapter four, to Nicola Lacey and Danny Priel for reading chapter five and to Susan Brock for reading chapter six. Last but in no sense least; I am grateful to James Boyd White. Not only because his published writing has exerted a great influence on my own work, but because he has been very generous in providing detailed observations on the long first chapter and after reading the book as a whole has been equally generous in commending it to the reader. Gary Watt, Spring 2009

xi

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 5 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 12 SESS: 7 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Prelims

/Pg. Position: 6 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 1 SESS: 11 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

1 Excursion I have purposely dwelt upon the romantic side of familiar things. Charles Dickens

T

HESE WORDS FROM the preface to the first edition of Bleak House are a fitting preface to the present study on the idea of equity in law and literature. My aim in writing this book is to reassert equity’s power to provide an ethic for imagining better law and better life. My method is to disclose the story – the roman – of justice beyond the familiar texts of law. One feature of this method is to read the texts of law alongside a wide variety of other literary texts – the inquiry is in that sense con-textual. Another, and interrelated, feature is to read legal texts in a wider variety of ways – the inquiry is in that sense a reading of the sub-text of law. Sir Frederick Pollock wrote that ‘English-speaking lawyers…have specialised the name of Equity’.1 It is typical for legal textbooks on the law of equity to acknowledge the diverse ways in which the word ‘equity’ is used and then to focus on the legal sense of the word to the exclusion of all others.2 There may be a professional responsibility on textbook writers to do just that. If so, there is a counterpart responsibility to read the specialist language of the law imaginatively and to read what non-lawyers have said of equity with an open mind. If one accepts that there is an inevitable disjunction between general law and more perfect justice, it follows that one should continually stir up what the law sets down. Lawyers tend to regard the idea of equity as if it were a door having one side within the law and one side without. They prefer to keep the door closed and to see only their side of it. I will argue that the legal language of equity is not so perfectly framed as to enable the door to be shut tight, and that this is a

1 F Pollock, Introduction and Notes to Sir Henry Maine’s ‘Ancient Law’ (London, John Murray, 1908) 14–15. 2 The classic text, Snell’s Principles of Equity does this. In at least one previous edition it opened with the line: ‘The term equity is used in various senses’ (HG Rivington and AC Fountaine (eds), 20th edn (London, Sweet and Maxwell, 1929).

1

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 1 /

Date: 16/4

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 2 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion good thing. The essentially fictional nature of legal language keeps the door ajar to stories of equity from beyond the law.3 It is normally unnecessary to reach beyond the letter of the law, but the need to do so is sometimes clear. The need is most obvious where harm is caused in a particular case through a party’s strict insistence on a legal rule, where such harm would not have occurred but for the existence of the legal rule. Suppose a landowner orally promised to appoint a vulnerable servant to be heir to the land and, as a result of the promise, the landowner received unpaid labour from the servant for many years. The parties’ informal agreement has no status in law because the general rules state that interests in land must be transferred by formal documentation, but the landowner ought surely to be required to honour the agreement. In these circumstances, the lack of legal form must not be permitted to defeat the promise. Every system of justice has a responsibility to supervise the operation in relation to particular people in particular cases of its general and necessarily imperfect scheme and to intervene to prevent harm caused by routine insistence on legal form and legal norms. This is the intervention of equity. Maine suggested that equity claims to override the general law on the ‘strength of an intrinsic ethical superiority’,4 but ‘superiority’ is the wrong word; ‘supervisory’ is better. Equity is not free-standing; it has no existence apart from its relationship to a general state, such as the general state of the law. Since it is dependent, it cannot claim to be superior; but it can claim to provide a necessary contribution to better justice. To correct the errors of the general scheme where they are apparent will not make the system ideal, but it will at least improve it by removing the worst and most blatant harms arising from the inadequacy of the law’s generality. Erik Rabkin sees a parallel to this pragmatic equitable dynamic in the fairy tale of The Sleeping Beauty.5 According to Perrault’s version, a wicked fairy attended the christening of the Princess Aurora and bestowed a curse instead of a gift. She promised that Aurora would one day pierce her hand with a spindle and on that day ‘surely die’.6 After this, the good fairy godmother Hippolyta conferred her christening gift on the child. She did not have the power ‘wholly to undo’ the wicked fairy’s prophecy, but she could at least commute the sentence of death to one of sleep. Equity cannot remove the force of the law, but it can moderate its impact. Equity does not break rules, but merely bends them.7

3 On the fiction of legal language, see generally, O Barfield, ‘Poetic Diction and Legal Fiction’ (the essay has been reproduced in several collections, including GB Tennyson (ed), A Barfield Reader: Selections from the Writings of Owen Barfield (Wesleyan University Press, 1999). Particular aspects of Barfield’s essay are considered in ch 4 at 138). 4 Henry S Maine Ancient Law (London, John Murray, 1861) ch 3; (London, Dent ‘Everyman’ edn, 1917) 43. 5 E Rabkin, ‘Fantasies of Equity’ in D Carpi (ed), Practising Equity, Addressing Law: Equity in Law and Literature (Heidelberg, Universitätsverlag Winter, 2008) 71−88, 79. 6 The Sleeping Beauty and Other Fairy Tales from the Old French retold by Sir Arthur QuillerCouch (London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1912) (reprinted London, Folio Society, 1998) 6. 7 In ch 3, we will consider a number of examples of this dynamic in the English Court of Chancery.

2

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 2 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 3 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion If a general rule causes harm in the generality of cases, that is not a problem calling for an equitable solution, but a problem calling for more radical law reform, by judges if possible or by parliament if necessary. The present study is an examination of this pragmatic idea of moderating equity as it emerges across a wide range of literary disciplines; including disciplines which, like law, perform text. It is, in a sense, a peregrination – a search for the idea through many fields. The hope is to correct formalistic errors in the way that law is read and, more aspirationally but no less important, to address the widespread error of reading life in terms of law; which we commit, for instance, when we unjustly and unreasonably insist on our strict legal rights and entitlements and also when we lead (and read) life according to unthinking routines. Hart distinguished rules of habitual behaviour – every week we go to the cinema ‘as a rule’ – from rules which we are compelled to obey – ‘there is a rule that a man must bare his head in church’.8 The equity that I have in mind transcends Hart’s distinction because it corrects the practical harm which flows from the error of general routine whether compliance with the routine is compelled or not. There is force at work in both cases, whether it is a force of public censure or a force of habit. I have in mind what James Boyd White refers to as ‘the Empire of Force’9 – which is the dominance of unthinking routines and norms. We see this force at work in habits, cliché, generalities, stereotypes, lazy labels and rigid routines. It is also to be found in the natural temptation to judge by external appearances. It is also found in errors of formalism and normalism (which I am aware is not normally a word). I have already made the formalistic error of assuming that there is such a thing as ‘a lawyer’. We should hope that there is in fact nobody for whom ‘lawyer’ is anything but a temporary and partial label. ‘Lawyers, I suppose, were children once’, said Charles Lamb;10 and it is also true that those who were lawyers once may be lawyers no more. Even Shakespeare and Dickens, the two writers who will contribute most to our literary appreciation of equity, had backgrounds that were in various senses ‘legal’, as we shall see in future chapters.11 It is only in fiction, one hopes, that one finds characters, like Dickens’ Mr Tulkinghorn, who are all law and all routine (we are told that even when he opens a door he does so ‘exactly as he would have done yesterday, or as he would have done ten years ago’)12 (41) and yet it is only in fiction, one suspects, that one finds characters who are utterly unconcerned with law and 8

HLA Hart, The Concept of Law (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1961) 10. JB White, Living Speech: Resisting the Empire of Force (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2006), reviewed by J Etxabe (2008) 2(1) Law and Humanities 138–46. 10 C Lamb, The Complete Works and Letters of Charles Lamb, The Essays of Elia, The Old Benchers of the Inner Temple (New York, Random House, 1935) 79–80. This quotation is the epigraph to Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (Philadelphia, JB Lippincott & Co, 1960). 11 The Dickens’ family had a very mixed experience of law. Charles’ father was imprisoned for debt and one of his sons, Henry Fielding Dickens, was appointed Queen’s Counsel. 12 I have adopted the practice of placing the chapter number immediately after the quotation in the main body of the text. This will be my practice in all remaining chapters. All quotations are taken from Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1852−3) (Harmondsworth, Penguin English Classics, 1971). 9

3

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 3 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 4 SESS: 15 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion utterly free from routine. The present study looks to the example of characters (real and fictional) who live, as we all live, somewhere between the extremes of utter legality and utter liberality. These are the characters who tell the story of justice beyond law. It is they who keep equity stirring.

Equitable Reading … the spectator or reader, if he or she reads well, is already prepared for equity and, in turn, for mercy. Martha C Nussbaum13

To read well means to read with an appropriate ethic, or, as it has been termed, an appropriate ‘poethic’.14 In the search for justice beyond the letter of the law the most appropriate ethic of reading is the equitable ethic. To read equitably is to read in the Aristotelian tradition of epieikeia, which Nussbaum calls a ‘gentle art of particular perception’ and ‘a temper of mind’ consistent with ‘understanding the whole story’.15 It is an ethic consistent with the hermeneutical tradition of the interpres aequus, the ‘equitable interpreter’ praised by Erasmus.16 The equitable temper of mind does not deny the need for temporary and partial labels like ‘lawyer’, but undertakes responsibility to read beyond them. Michel de Montaigne had inscribed into the rafters of his library certain mottos translated from the Skeptic philosophy of Sextus Empiricus, including ‘I determine on nothing’ and ‘I do not comprehend’ and ‘I suspend judgment’.17 DH Lawrence wrote something similar when he wrote that ‘[a]nger is just, and pity is just, but judgment is never just’.18 For Montaigne, sceptism did not close inquiry, but was a spur to further and better examination. He was a former lawyer who has been called ‘one of the greatest, and most human, of the humanists’19 and he indicates a path for every lawyer to follow. Lawyers might discern the start of the path to equitable reading in such juridical notions as ‘the equity of a statute’20 and the ‘benevolent construction’21 of documents. The tradition of equitable reading is in fact as long-established in 13

MC Nussbaum, ‘Equity and Mercy’ (Spring 1993) 22(2) Philosophy and Public Affairs 83–125 at

105. 14 RH Weisberg, Poethics: And Other Strategies of Law and Literature (New York, Columbia University Press, 1992). 15 ‘Equity and Mercy’, above n 13 at 92. See generally, FD ‘Agostino, Epieikeia. Il tema dell’equità nell’antichità greca (Milano, Giuffrè, 1973). 16 K Eden, Hermeneutics and the Rhetorical Tradition: Chapters in the Ancient Legacy and Its Humanist Reception (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1997) 3 and ch 4. 17 See L Floridi, Sextus Empiricus: The Transmission and Recovery of Pyrrhonism (New York, Oxford University Press US, 2002) 40–44. 18 DH Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (New York, Viking Press, 1922) 17–18. 19 G Highet, The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature (New York, Oxford University Press US, 1949) 193. 20 See eg, Sir John Jackson Limited v Owners of the Steamship ‘Blanche’ Her Master and Crew [1908] AC 126 (HL) 135 (Lord Atkinson). See also, generally, RB Marcin, ‘Epieikeia: Equitable

4

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 4 /

Date: 29/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 5 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Equitable Reading English law as the more familiar idea of equity as a source of supplemental remedies.22 The early modern stage of that tradition is marked by Plowden’s extensive exposition on the equity of the statute in Eyston v Studd,23 which in turn was echoing book five of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics. Plowden said the letter of the law is the body of the law, and the sense and reason of the law is the soul of the law [and] it is a good way, when you peruse a statute, to suppose that the lawmaker is present, and that you have asked him the question you want to know touching the equity; then you must give yourself such an answer as you imagine he would have done, if he had been present.24

Allen acknowledges that although this ‘may seem naïve’, ‘it is not an altogether fantastic description of the feat of imagination which Courts still have to perform in endeavouring to “carry out the intention of the legislature’”.25 As recently as 2006, Lord Hope acknowledged in the House of Lords that ‘a statute is always speaking…where the language permits there is this element of flexibility. It can be adapted to contexts that were not foreseen when it was enacted’.26 Judges are generally wary of looking to the ‘equity of the statute’ and prefer to read statutes as literally as possible.27 Such caution is understandable. There is always danger beyond the letter of the law, which in extreme cases is extreme danger – it has been observed, for instance, that the National Socialists established fascism in Germany through a prerogative reading of legal codes drafted in the non-fascist Weimar Republic.28 In Vichy France, the Nazis’ prerogative reading of laws was just as extreme.29 And yet it is precisely because terrible things may lurk between the lines of laws, that the equitable art of reading beyond the letter must be cultivated – and cultivated by an appropriate ethic. The alternative is to refuse to Lawmaking in the Construction of Statutes’ (1978) 10 Connecticut Law Review 377, 392–97; SE Thorne, ‘The Equity of a Statute and Heydon’s Case’ (1936) 31 Illinois Law Review 202; WH Loyd, ‘The Equity of a Statute’ (1909) 58 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 76, 76–86. JF Manning, ‘Textualism and the Equity of the Statute’ (2001) 101 Columbia Law Review 37 contains a useful history of the concept, albeit to argue that the concept is peculiarly English and does not readily translate into US constitutional interpretation. 21 See eg, IRC v Cook [1946] AC 1, 10 (HL). 22 See L Hutson, ‘Not the King’s Two Bodies’ in V Kahn and L Hutson (eds), Rhetoric and Law in Early Modern Europe (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2001) 166−198, 171. 23 Eyston v Studd (1574) Plow 459. 24 Ibid at 465ff. 25 CK Allen, Law in the Making 4th edn (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1946) 374. 26 Powerhouse Retail Ltd v Burroughs [2006] UKHL 13 para [26]; [2006] ICR 606, 615. 27 Brandling v Barrington (1827) 6 B & C 467 at 475 (Lord Tenterden CJ); Vacher’s Case [1913] AC 107 at 130 (Lord Moulton). 28 M Franklin, ‘A New Conception of the Relation Between Law and Equity’ (1951) 11(4) Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 474–88, 483; discussing Ernst Fraenkel, The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1941). 29 Weisberg, Poethics, above n 14 at 136–87. See generally, B Durand, J-P Le Crom and A Somma (eds), Droit sous Vichy (Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 2006).

5

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 5 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 6 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion look beyond the letter at all, but such capitulation would merely replace the error of abusive reading beyond the law with the error of abuses caused by reading the law too strictly. There are dangers of extremism within the letter as much as without, which is why Radbruch wrote (in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust) that we ‘arm ourselves against the recurrence of an outlaw state like Hitler’s by fundamentally overcoming positivism’.30 Perhaps the message was heard, for it has been said that the search for the equity of the statute is nowadays ‘indispensable’ in countries governed by a civil code.31 Equitable reading should be considered equally indispensable in common law jurisdictions, especially in jurisdictions deluged by a superfluity of legislation. The United Kingdom is one such. In August 2006, an article in The Independent newspaper recorded that the government under Tony Blair had created more than three thousand new criminal offences during the nine years of its tenure to that date – ‘one for almost every day it has been in power’.32 It would take a blind faith indeed to believe strictly in the letter of laws spewed forth at such a rate. The Human Rights Act 1998, which confirmed the binding status in UK law of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1950) (‘ECHR’) takes a step towards revitalising the tradition of equitable interpretation by requiring that ‘so far as it is possible to do so’ UK legislation ‘must be read and given effect in a manner which is compatible with the Convention rights’.33 This is a significant step, because it admits a principle of ‘benevolent construction’, but it is also a modest step because it does not permit a statute to be construed ‘contrary to its plain meaning’;34 and nor should it. An equitable reading is never contrary to plain meaning even if the judge must occasionally read beyond the simplicity of an isolated statement in order to understand the plain meaning of the statement in the context of the statute as a whole. If the statute as a whole does not completely anticipate a particular case, and no statute 30 G Radbruch, ‘Gesetzliches Unrecht und U¨bergesetzliches Recht’ first published in (1946) 1 Süddeutsche Juristen-Zeitung 105–08 (trans BL Paulson and SL Paulson, ‘Statutory Lawlessness and Supra-Statutory Law (1946)’ (2006) 26(1) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 1–11, 8). 31 S Herman, ‘The “Equity of the Statute” and Ratio Scripta: Legislative Interpretation Among Legislative Agnostics and True Believers’ (1994) 69 Tulane Law Review 535, 538. 32 N Morris, ‘Blair’s frenzied law making’ The Independent (16 August 2006). 33 S 3(1). In R v A (No 2) [2002] 1 AC 45, the House of Lords relied on the right to a fair trial established by Article 6 of the ECHR when permitting the defendant in a rape trial to refer to his shared sexual history with the complainant. This was despite s 41 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999, which for most purposes prohibited the defendant from making reference to the complainant’s sexual history. In the US, any genuinely ambiguous provision in a statute will be read where possible in a way that will not cast doubt on its constitutionality (Ashwander v Tennessee Valley Authority 297 US 288 (1936)). 34 Levi Strauss & Co. and Levi Strauss (UK) Ltd v Tesco Stores Ltd, Tesco Stores Plc and Costco Wholesale UK Ltd [2002] ETMR 95; [2000] EWHC 1556 (Ch D) [44] (Pumfrey J). In R (Wilkinson) v IRC [2005] UKHL 30; [2005] 1 WLR 1718 (HL), a widower failed when he argued that in order to avoid sex discrimination, a fiscal statute conferring an entitlement on widows ought to be interpreted as conferring the same entitlement on widowers. Discussed in Jan van Zyl Smit, ‘The New Purposive Interpretation of Statutes: HRA Section 3 after Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza’ (2007) 70(2) Modern Law Review 294–306.

6

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 6 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 7 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Equitable Reading can anticipate every case, equity must also make plain sense of that. Hence Pomeroy’s contention (following Aristotle) that equity should supplement ‘the provisions of a statute’ even where they are ‘perfectly clear’ if they ‘do not in terms embrace a case which, in the opinion of the judge, would have been embraced if the legislator had carried out his general design’.35 The tradition of equitable reading has largely been marginalised in English law, although one suspects that it thrives disguised in the default language of ‘policy’. That is an unfortunate disguise. The saying is true – ‘policy is an unruly horse’. Equity, on the other hand, presents the very picture of a wild horse bridled – neither rule-bound nor unruly – as we shall see in future chapters. It was once thought that the tradition of equitable reading has no place in the context of fiscal statutes: [i]n a taxing act one has to look merely at what is clearly said. There is no room for any intendment. There is no equity about a tax. There is no presumption as to a tax. Nothing is to be read in, nothing is to be implied. One can only look fairly at the language used.36

Yet even here, the judicial instinct could not resist the equitable urge to ‘look’, not literally, but ‘fairly’ at the statutory language; and it has since been acknowledged that the principle of looking beyond the literal meaning of language is applicable to all statutes.37 A more generous species of equitable reading of statutes has always been of central significance to the law of charity. Today a charitable purpose is one within a list of charitable purposes set out in the Charities Act 2006 or ‘any purposes that may reasonably be regarded as analogous to, or within the spirit of’ that list.38 This replaces the previous law which provided that a charitable purpose was any purpose deemed to be ‘within the spirit and intendment’ of the preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses (1601),39 which phrase was held to be synonymous with ‘the equity of the statute’.40 The authorities demonstrate an appropriate lack of confidence in the strict letter of the law of charity and this is surely because the concept of charity has been imported, loaded with meaning, from languages beyond the law. As the Lord Chancellor, Lord Cairns, once said: ‘there is, perhaps, not one person in a thousand who knows what is the technical and the legal meaning of the term “charity”’.41 Lord

35 JN Pomeroy, A Treatise of Equity Jurisprudence (in three volumes) vol I (San Francisco, AL Bancroft and Co, 1881) 36 (para [44]). 36 Cape Brandy Syndicate v IRC [1921] 1 KB 64 at 71 (Rowlatt J). 37 In WT Ramsay Ltd v Inland Revenue Commissioners [1982] AC 300 (HL) Lord Wilberforce confirmed that a subject is only to be taxed upon clear words, but confirmed (at 323C–D) that ‘clear’ meaning is not limited to ‘literal’ meaning. See also, IRC v McGuckian [1997] 1 WLR 991, 998–99 (HL). 38 Charities Act 2006 s 2(4)(b), (c) (emphasis added). 39 43 Eliz I c.4. 40 Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales v Attorney-General [1972] Ch 73 at 88 (Russell LJ); Dolan v Macdermot (1867–68) LR 3 Ch App 676, 678. 41 Dolan v Macdermot, ibid.

7

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 7 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 8 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion Macnaghten (who once admitted that ‘nobody by the light of nature ever understood an English mortgage of real estate’)42 could only achieve clarity in the legal language of charity, by artificially cleaving it from the common sense of the word: Of all the words in the English language bearing a popular as well as a legal signification I am not sure that there is one which more unmistakably has a technical meaning in the strictest sense of the term, that is a meaning clear and distinct, peculiar to the law as understood and administered in this country, and not depending upon or coterminous with the popular or vulgar use of the word.43

Lord Macnaghten admits that the law has captured charity and specialised the sense of the word charity in much the same way that I say it has captured and specialised equity. The concept of equity was imported into the law as the concept of ‘charity’ was imported and should be approached with the same humility.

The Constancy of Remedial Equity The effort to encapsulate the distinctly non-legal concept of charity in legal terms has produced a law of charity which is not very systematic at all; indeed it is not so much ‘law’ as a catalogue of individual cases loosely connected by certain broad factors, the most significant being the fact that they are officially considered to confer benefit on the public. Lord Kames could have been speaking of the English law of charity today when he said of charity that ‘the wisest heads would in vain labour to bring it under general rules’.44 What Lord Kames said about charity, Maitland said about equity in English law when he observed that it is ‘a collection of appendixes between which there is no very close connection’ and that if the law were ‘put into systematic order, we shall find that some chapters of it have been copiously glossed by equity, while others are quite free from equitable glosses’.45 It is true that equity, like charity, cannot be wholly contained within the confines of systematic general law, but this is not because these ideas lack coherent meaning, it is simply that these ideas have meanings which go beyond meanings that can be categorised in general law. The apparent unevenness of equity’s intervention in law is not attributable to the nature of equity but to the rigidity of the law. When rigid general law is laid upon the uneven ground of nature it will touch at certain points and miss at others. Aristotle attributes the fault, not to law, but to the unevenness of nature: 42

See ch 3 at 130. Commissioners for Special Purpose of the Income Tax v Pemsel [1891] AC 531 at 581. 44 HH Kames, ‘Introduction’ in Principles of Equity (1760) (Edinburgh, Bell & Bradfute, 1825) 15. 45 FW Maitland, Equity: A Course of Lectures 2nd edn (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1936) 19. 43

8

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 8 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 9 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

The Constancy of Remedial Equity In those cases, then, in which it is necessary to speak universally, but not possible to do so correctly, the law takes the usual case, though it is not ignorant of the possibility of error. And it is none the less correct; for the error is not in the law nor in the legislator but in the nature of the thing.46

Wherever one lays the blame, there is undeniably a fault between strict law and nature – including human nature. Sometimes the law fits with nature, and sometimes it does not. Equity is only required to intervene where the law misses, but this does not mean that equity is inconsistent any more than different shadows cast by different hills indicate inconsistency in the sun. Of course equity appears inconsistent if one is committed to the fiction that law is fixed and infallible, but life does not revolve around the law any more than the sun revolves around the earth. When one looks beyond the law one sees that equity is consistent in its approach, because it has a consistent attitude or ethos. Sir JW Jones understood this: [T]he unwritten law, in its aspect of what equity or fairness requires in the case…can be accorded an element of generality in that the attitude of approach represented by it towards special problems expresses a fundamental human striving to fill the gap which constantly opens between enacted law and the calls of justice.47

The only word in this passage which is doubtful is ‘generality’. ‘Constancy’ is a better word. Equity is a constant attitude. It is, I would suggest, very similar to what Hegel called a ‘living unity’, which is virtuous because it does not have a constant form but constantly accommodates the contours of life: [A] living unity, is quite different from the unity of the concept; it does not set up a determinate virtue for determinate circumstances, but appears, even in the most variegated mixture of relations, untorn and unitary. Its external shape may be modified in infinite ways; it will never have the same shape twice. Its expression will never be able to afford a rule, since it never has the force of a universal opposed to a particular.48

When I describe equity as a constant attitude and a living unity, I mean of course that equity is applied by human judges – not just those in courtrooms but by all of us. It is therefore incumbent on us all constantly to bend the rules where they

46

Aristotle, The Nichomachean Ethics book 5 ch 10 (trans WD Ross). J Walter Jones, The Law and Legal Theory of the Greeks (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1956) 67. Holdsworth also sees a unity in the principles underlying equity. He even suggests that equity imposes ‘distinct intellectual characteristics…upon those who study the principles and rules of equity’ (William S Holdsworth, ‘Equity’ in AL Goodhart and HG Hanbury (eds), Essays in Law and History by Sir William S Holdsworth (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1946) 185; originally published at (1935) 51 Law Quarterly Review 142). This is a fairly oppressive image of equity’s effects. It would be more pleasing and more precise to say that contemplation of (and practice in) equity has the potential to engender a distinctive ethical approach to law, which we might call an ethic that is critically corrective of the law but does not undermine it. 48 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, ‘The Spirit of Christianity’ in TM Knox (trans) and R Kroner (introduction), GWF Hegel: Early Theological Writings (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971) 246. This passage is quoted in an essay on equity by the philosopher John Lucas: ‘The Lesbian Rule’ (1995) 1 Philosophy 195, 196. 47

9

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 9 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 10 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion cause harm through their rigidity. As for routines, it is commonly said that a routine is either ‘followed’ or ‘broken’; but perhaps even routines are better bent than broken. Some routines require instant and radical reform, but for more mundane matters it may be that change by ‘nudges’ better accords with the practical contingency of the way we live and the psychological reality of the way we think.49

The ‘Science’ Fiction of Law The strictness, generality, formality and routine of legal rules combine to create a gap – an ‘equity gap’ – between the general law and more pleasing justice. Even if we fantasise that there might come a moment when the law, in all its formal and flexible aspects, will be considered perfectly fitting with every eventuality of a given society, one can be sure that such a society will change faster than its law, so time itself will open up the gap between the law and more pleasing justice. A great deal of judicial and scholarly effort is devoted, rightly, to the removal of internal illogicality and vagueness from the law – this is the scientific or doctrinal school of jurisprudence. A comparable effort is devoted no less properly to understanding the social influences which produce the law and which produce the ever-open gap between law and society. It would be a mistake to assume, though, that it is within the competence of jurisprudential science or the empirical science of legal sociology ever to get the full measure of justice. I am with John Lucas who believes that ‘the complexity and variableness of human beings is infinite’ and that this precludes us ‘from hoping that scientific generalization ever would become practicable in the humanities’.50 When Kiss wrote that ‘the problem of how to apply the law cannot be solved scientifically except by considering the problem of unprovided cases’,51 he was right to identify the problem of ‘unprovided cases’ – which is the problem of the equity gap – but he was wrong to suppose that there is a scientific solution to that problem, just as Langdell was wrong when he famously asserted ‘that law is a science’.52 They were writing at a time when the paradigm of empirical science was paramount and imagined itself separate and superior to the arts and humanities. Now we see, as Lucas sees, that in conceptual terms ‘the difference between the humanities and 49 For a stimulating commentary on this phenomenon, see RH Thaler and CR Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2008). 50 Lucas, ‘The Lesbian Rule’, above n 48. 51 G Kiss, ‘Equity and Law: Judicial Freedom of Discretion’ in Science of Legal Method: Selected Essays (Boston, Boston Book Company, 1917) 146–58. 52 CC Langdell, ‘Harvard Celebration Speech’ (1887) 3 Law Quarterly Review 123, 124. See P Goodrich, ‘Druids and Common Lawyers. Notes on the Pythagoras Complex and Legal Education’ (2007) 1(1) Law and Humanities 1, 18. Goodrich notes Stevens’ suggestion that Langdell confused two types of science – the empirical and the rational (R Stevens, Law School. Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill, NC, North Carolina University Press, 1983)).

10

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 10 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 11 SESS: 14 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

The ‘Science’ Fiction of Law science is one of degree rather than one of kind’.53 Science at its furthest frontier is a world of pictures: it is a cosmos of ‘black holes’, ‘curved space’ ‘string theory’ and ‘waves of light’. My project is not opposed to legal science, but I do oppose the notion that legal science is sufficient without legal art. Colin and Capitant, who were leading commentators on the French Civil Code, asked of the law ‘est-il une science ou un art?’ and concluded that it is both.54 Even in Germany, where faith in legal science (rechtswissenschaft) is profound, concession is made to discretionary relaxation of the rules in particular cases – which is called billig Ermessen or Billigkeit.55 The equitable mode of reading the Code is also deeply embedded in German legal culture. Bussani and Fiorentini observe ‘how wide is the portal through which this kind of equity finds its way into German private law’, noting that: This portal is kept open by the Treu und Glaube [‘good faith’] principle of § 242 BGB, as well as by the other Generalklauseln requiring judgments to be based upon good morals (gute Sitte) or necessary care (erforderliche Sorgfalt),56 all of which oblige the judge to seek the legal grounds for the decision elsewhere than in positive law [57]…§ 242 and the other Generalklauseln provide legitimacy to the equitable work of the interpreter, enabling the latter to exploit his/her reservoir of legal culture outside the boundaries of positive law.58

If the art of equity is always necessary in jurisdictions which subscribe to the sanctity of a legal code, we should not be surprised to find that it is even more prominent in common law jurisdictions, which have no overarching code but rely to a great extent on judicial creativity in particular cases. With regard to statutory interpretation, one of the Law Lords of England and Wales has provided an emphatic answer to the question posed by Colin and Capitant – ‘le droit est-il une science ou un art?’ Lord Steyn has stated that the interpretation of a statute ‘is not a science. It is an art’.59 Case law develops in England and other

53

Lucas, ‘The Lesbian Rule’, above n 48 at 199. A Colin and H Capitant, Cours élémentaire de droit civil français (Paris, Librairie Dalloz, 1931) vol I at 6, para [5] (first published 1914–16). 55 German BGB, paras: 315, 571, 829, 920, 1246, 1360a, 1361, 1361a, 1361b, 1576, 1577, 1581, 1587 I, 1611, 1649, 2057a. See generally, P Gottwald, Münchner Kommentar zum BGB, 2a 4th edn (Munich, CH Beck, 2003) RdNr 30, 1874 § 315. (All references in this note are from M Bussani and F Fiorentini?, ‘The Many Faces of Equity. A Comparative Survey of the European Civil Law Tradition’ in D Carpi (ed), The Concept of Equity (Heidelberg, Universitätsverlag Winter, 2007) 101–49, 122, fn 82.) 56 ‘BGB, §§ 138, 817, 819, 826 (regarding good morals); §§ 241a II, 259 II, 276 II, 831 I, 833 s., 836, 2028 II (regarding necessary care).’ (This text taken from the footnote in the original.) 57 The original (long) footnote begins with the words: ‘Literature on § 242 is simply enormous’. The reader is directed to consult the original. In brief, the authors observe that the origin of § 242 lies ‘in the bona fidei iudicia of Roman law and the equitable creation of law by the praetor’ (they cite MJ Schermaier, ‘Bona fides in Roman Contract Law’ in R Zimmermann and S Whittaker (eds), Good Faith in European Contract Law, The Common Core of European Private Law Project (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000) 63ff). 58 Above n 55 at 123. 59 ‘The Intractable Problem of the Interpretation of Legal Texts: The John Lehane Memorial Lecture 2002’ (2003) 25 Sydney Law Review 1, 8. 54

11

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 11 /

Date: 24/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 12 SESS: 14 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion common law systems in a way which could hardly be called scientific. Cases are the experimental basis of legal ‘science’ in common law jurisdictions, but they are in no real sense empirical, because legal cases are experiments that cannot be repeated. Even if similar cases recur, it is not possible to predict outcomes with anything close to the levels of statistical certainty which would normally be required to establish a scientific proof. Take the example of a recent case in which a farmer claimed to have acquired legal title to another person’s (very valuable) land through the process of ‘adverse possession’ (commonly referred to as ‘squatting’). The judge at first instance reluctantly held in favour of the farmer.60 The Court of Appeal reversed that decision on appeal,61 but on further appeal to the House of Lords the judgment at first instance was restored by their Lordships – again reluctantly.62 The decision was then referred to the European Court of Human Rights (Former Section IV) in Strasbourg63 where UK law on the subject was disapproved, until finally it was appealed to the European Court of Human Rights (Grand Chamber)64 where the UK law was finally upheld. So the matter passed through five courts and each court in broad terms disagreed with the decision of the previous court. So long as litigation relies on fallible judges for resolution, we should not expect a perfect legal science.65 There is never only one answer to a legal dispute; indeed it is a rare case that has only one right answer. As Lord Macmillan admitted: ‘in almost every case except the very plainest, it would be possible to decide the issue either way with reasonable legal justification’.66 Ronald Dworkin fantasises that there is always one right answer to every case and that a hypothetical Herculean judge could find it.67 Perhaps Hercules might, but then perhaps Zeus would find another answer on appeal. Some jurists might like to regard the courts in the case of the squatter as a series of laboratory glasses in a grand scientific experiment which ultimately produces the correct compound at one end from the raw factual materials which went in at the other. Of course it is nothing of the sort. The system of judicial appeals is not a scientific process which produces an objectively correct outcome, the outcome often turns in large part on the purely practical contingency of running out of courts. The nature of law in such a system is less like a scientific experiment and more like a wheel of fortune: the nature of the legal outcome is determined at the point the wheel stops spinning, and would have determined earlier if the litigants had been at any stage unwilling, or financially unable, to give it an extra push. From the judges’

60

JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v Graham [2000] 3 All ER 865. [2001] EWCA Civ 117, [2001] Ch 804. JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v Graham [2002] UKHL 30, [2003] 1 AC 419. 63 JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v United Kingdom (App no 44302/02) ECHR 15 November 2005. 64 JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v United Kingdom (App no 44302/02) ECHR 8 November 2006. See O Radley-Gardner, ‘Good-Bye to Pye’ [2007] 5 Web JCLI (online). 65 See generally, L Rosen, Anthropology of Justice: Law as Culture in Islamic Society (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989). 66 HP Macmillan, Law & Other Things (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1937) 48. 67 R Dworkin, Law’s Empire (Harvard, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986). 61 62

12

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 12 /

Date: 24/6

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 13 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

The ‘Science’ Fiction of Law perspective it is a living conversation across a range of reasonable alternative possibilities, and it just happens that the conversation must stop sometime. Law is not a pure empirical science, and, by the same token, it is not a pure logical science. Holmes’ aphorism has been so often-repeated, it has become trite; but it is nevertheless true: ‘The life of the law has not been logic: it is has been experience’.68 This is seen clearly even in an area of law which is supposed to be more logical than most – the law governing the conveyance of real property. Suppose Jack borrows money from a bank with a view to purchasing a house and promises that, as soon as the land is acquired, he will grant the bank a charge over the land by way of security. Now suppose Jack enters into occupation of the house prior to completing the purchase, so that he is in occupation the moment title is transferred into his name. Logically there can be no charge on his title until Jack has title to charge, so the moment ‘A’ at which Jack acquires title must be prior to the moment ‘B’ at which the bank acquires a charge on his title. According to strict logic, it follows that Jack is in occupation with unencumbered title prior to his being in occupation with title encumbered with the charge. His contract with the bank bars him from claiming to have priority over the bank; but suppose that his lover, Jill, was in occupation with him at all times and is not subject to the contract, and suppose that she had contributed the cash for the deposit on the house, so that Jack holds his title on trust not only for himself but also (as to some beneficial share) for her. According to strict logic, Jill is in occupation with a share before the bank has its mortgage and because Jill has no contract with the bank she is not barred from asserting the priority of her interest over that of the bank (assuming such background factors as proper behaviour by all parties throughout the relevant period). The outcome, under which Jill remains in occupation even if Jack is evicted for defaulting on the loan, is unfair to the bank. How can Jill’s interest in the house take priority over the bank’s when the lovers would have had no house at all were it not for the money loaned by the bank? Property law logic leads to an unjust outcome. Faced with a case of this sort, the House of Lords has held that the mortgagee’s charge should take priority over the interest of the mortgagor’s lover. Logic was rejected in favour of experience:

68 OW Holmes, The Common Law (1881) (Stilwell, KS, digireads.com, 2005) 1. The problem with Holmes’ engagement with experience is that it was sometimes more terrifyingly calculating than any system of logic. His decision in Buck v Bell 274 US 200, 207 (1927) to allow the compulsory sterilisation of a young mentally disabled woman who was an inmate of a state institution was delivered in terms which nowadays beggar belief. Holmes’ argument was that citizens who contribute to society’s welfare may be called upon to die for their country, so those who ‘sap the strength of the state’ should be called upon to sacrifice their reproductive capacity. Hence his infamous dictum: ‘three generations of imbeciles is enough’. It is notable, and may be significant, that this phrase was uttered by the man who once said that ‘the law is not the place for the artist or the poet’ (‘The Profession of the Law’ in Collected Legal Papers (New York, Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920) 29 at 29–30)).

13

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 13 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 14 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion [A]s a matter of legal theory, a person cannot charge a legal estate that he does not have, so that there is an attractive legal logic in [the argument that the purchaser acquires an unencumbered estate before the mortgagee acquires a charge on it]. Nevertheless, I cannot help feeling that it flies in the face of reality. …. The reality is that the purchaser of land who relies upon a building society or bank loan for the completion of his purchase never in fact acquires anything but an equity of redemption, for the land is, from the very inception, charged with the amount of the loan without which it could never have been transferred at all and it was never intended that it should be otherwise.69

This is a fascinating piece of judicial rhetoric. Property law logic has rightly been rejected in favour of common sense justice, but the learned judge is at pains to disguise the pragmatic nature of the decision in terms of an appeal to ‘reality’. On close examination, the ‘reality’ appealed to turns out to be a highly artificial form of legal fiction. His Lordship says that the purchaser of land ‘never in fact acquires anything but an equity of redemption’, but there is very little about an equity of redemption that exists ‘in fact’. It is about as complex a legal fiction as one can imagine. Even Lord Bramwell confessed that ‘one knows in a general… not in a critical way, what is an equity of redemption’.70 The reality of land is soil and three-dimensional space, from this the law abstracts an estate and from this a legal mortgage and from this an ‘equity of redemption’. Equity, which does not favour abstraction, is forced to adopt the fiction of an ‘equity of redemption’ to ensure that mortgagors remain in their homes despite the threat of eviction which accompanies the formal force of the legal mortgage deed. The legal ‘reality’, when we strip away the mythology of the mortgage of the fee simple and the equity of redemption, is simply that the mortgagor has the nearest thing to absolute title that English law knows, while the mortgagee acquires nothing but a charge on that title by way of security.71

The Cultural Story of other Countries and other Worlds To read what others say about equity within the law, and to read equitably, is to scrutinise the supposedly secure boundaries of the law by external lights. As James Boyd White has written:

69

Abbey National Building Society v Cann [1991] 1 AC 56 at 92F–93B (Lord Oliver). Salt v Marquess of Northampton [1892] AC 1 (HL) 18. 71 G Watt, ‘The Lie of the Land: Mortgage Law as Legal Fiction’ in E Cooke (ed), Modern Studies in Property Law – Volume 4 (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2007) 73–96. See also, ch 3 at 130. 70

14

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 14 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 15 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

The Cultural Story of other Countries and other Worlds Reading texts composed by other minds in other worlds can help us see more clearly (what is otherwise nearly invisible) the force and meaning of the habits of mind and language in which we shall in all likelihood remain unconscious unless led to perceive or imagine other worlds.72

We take a step in the right direction when we compare the laws of one national jurisdiction with the laws of another, and some fine work has been done to advance our understanding of equity in this way.73 The most sophisticated schools of comparative law examine the roots of laws – historical roots, political roots, economic roots and so forth. However, relatively little attention is paid to the cultural earth – by which I mean the literary earth, the artistic earth, the dramatic earth – from which the roots sprang and by which they continue to be nourished. In the end it will not suffice to look merely to the laws of other lands, we must, as White says, look to the literatures of ‘other worlds’. White has written that one of the merits of literature is that ‘it humiliates the instrumentally calculating forms of reason so dominant in our culture (by demonstrating their dependence on other forms of thought and expression)’.74 Consider the law’s reliance on the basic distinction between form and substance, with the correlative distinction between letter and intention. Are such ideas not dependent on distinctions embedded in cultural narrative, including cultural literature? Where would they be without the distinction between body and soul and the mythology of shape-shifting? One of the topics I teach my law degree students is the law of tracing, which governs the process of following the substantial value of an asset into another asset in the event of exchange. Here is a legal story in which substantial ‘value’ is maintained despite changes in outward form. It has an essential correspondence with tales of shape-shifting that recur in the cultural literature of societies worldwide. In European cultural literature this strand of story is exemplified in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and fairy tales such as ‘Dapplegrim’ (in which a princess pursued by a suitor changes into a duck and then a loaf and so forth).75 Robert M Cover was right, when he wrote: No set of legal institutions or prescriptions exists apart from the narratives that locate it and give it meaning. For every constitution there is an epic, for each decalogue a scripture. Once understood in the context of the narratives that give it meaning, law becomes not merely a system of rules to be observed, but a world in which we live.76

72

JB White, ‘What Can a Lawyer Learn from Literature?’ (1989) 102 Harvard Law Review 2014,

2022. 73 See eg, RA Newman (ed), Equity in the world’s legal systems; a comparative study (dedicated to René Cassin) (Brussels, Établissements Émile Bruylant, 1973). 74 JB White, ‘Law and Literature: No Manifesto’ (1988) 39 Mercer Law Review 739 at 741. 75 ‘Dapplegrim’ from The Red Fairy Book by Andrew Lang (1890). The tale is derived from the Norse fairy tale Grimsborken (see the Norske Folkeeventyr of PC Asbjørnsen and J Moe, translated into English by Sir George Webbe Dasent as Popular Tales from the Norse, 1859). 76 RM Cover, ‘Nomos and Narrative’ (1983) 97 Harvard Law Review 4, at 4–5.

15

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 15 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 16 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion The purpose of suggesting a connection between law and cultural literature is not to invite an empirical search for a causal connection between literature and the law – such a connection is presumably not susceptible to empirical proof or disproof. The purpose is to open the imagination to the possibility of a connection – this is enough to produce the desired reflective critique of the law’s assumed self-sufficiency. We might, for example, imagine the possibility that the peculiar prominence of equity (and the trust idea) in English law is not solely attributable to empirically quantifiable historical conditions, but might owe something to a cultural story, a national self-narrative of ‘Englishness’, one which is as much a maker of history as a product of it. The English self-narrative prides itself on a culture of tolerance and a suspicion of absolutist ideologies (including the ideologies of absolute monarchy, bloody revolution, religious extremism and fascism) and related to this is a sense of equitable compromise inherent in the assumed national preoccupation with bargaining and trade. Hence the Scottish author Sir Walter Scott writes of ‘natural notions of equity becoming a British merchant’.77 The fact that equity and the trust are opposed to extreme formality and the fact that the trust is neither absolutely property nor absolutely obligation might therefore go some way to explaining the reception and retention of such ideas in the English mind. In this vein, Professor Goodhart has suggested that Locke’s idea of government as a form of trust – the ‘legislative power’ being ‘limited to the public good of society’78 – is ‘especially congenial to English ideas and Traditions’.79 History will surely debunk English (or British) pretension to such ideals as ‘moderation’, ‘tolerance’, ‘restraint’, ‘fairplay’, ‘cricket’, ‘gentlemanly behaviour’ and ‘sportsmanship’, but the story trumps the history.

Law, Humanities and the Humane The present study aims to discover where the idea of equity, even equity as it appears in English law, has been planted and cultivated by the arts and humanities. The law is a discipline of letters, a discipline concerned with words and with ways of weaving words into texts. It is therefore assumed that law can learn from other disciplines concerned with letters and texts including such disciplines as literary studies, history, rhetoric, classics and theology. Much of the best work in the field of law and literature is currently undertaken by scholars in these disciplines looking in on the law from the other side of the door. I also assume that the law, as an art of performance and representation, can learn from theatre, 77 Sir Walter Scott, Rob Roy (Edinburgh, Archibald Constable; London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1817) ch 2. 78 John Locke, Second Treatise of Government ch XI section 135. See P Laslett (ed), John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1963). 79 AL Goodhart, ‘English Contributions to the Philosophy of Law’ (July 1948) 48(5) Columbia Law Review 671–88 at 677.

16

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 16 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 17 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

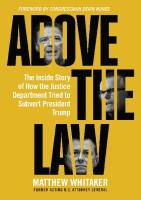

Law, Humanities and the Humane film, television, sculpture, painting and all the arts of performance and representation.80 The actor’s art is ‘to comprehend the thoughts that are hidden under words’,81 which makes it an art of equitable interpretation. It is now almost routine to distinguish law in literature (for example, the ‘trial’ in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird) from law as literature (for example, the judicial style of Justice Benjamin Cardozo) and law of literature (for example, the law of copyright).82 All these categories can be inverted, so we also have literature in law (for example, judicial reference to the works of Shakespeare),83 literature as law (for example, legal fictions) and literature of law (for example, the didactic poem, ‘The Pleader’s Guide’).84 There is of course, mainstream legal literature – including statutes, reported judgments and academic commentary. The reader is free to bear these categories in mind throughout this book, but I would caution against placing too much faith in them. For one thing, the categories may overlap and intersect in complex ways – it is possible to identify law as literature in literature, and so forth. Provided both disciplines are engaged in constructive critique of the other, one should be slow to place limits on the ways in which they might engage. Dolin says ‘it is not the role of literature to introduce love into an aridly rationalist law’.85 This must be true because any stereotypical opposition between law and literature is always a false opposition that obstructs us from seeing the potential for law to be literature and for literature to be law. However, if we expand the categories of law and literature into a world of laws and literatures we can easily imagine a role for a kind of literature to introduce love into a kind of law. Better still; let us ask not what literature and law can do for each other, but what law ‘and’ literature can do for us. True interdisciplinary inquiry has the power to bring people together because it is conducted with the ethos of ‘and’.86 It is appropriate at this point to mention the image on the cover of this book. It shows a bird perched on the open door of its cage, looking to the world beyond. We will find that the image is pertinent to the portrayal of equity in Dickens’ Bleak House, but for now it will suffice to say that the uncaged bird is intended to represent equity beyond the confines of general law. Like a peregrine bird, the

80 See S Levinson and JM Balkin, ‘Law, Music, and Other Performing Arts’, (1991) 139 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1597. I compare theatre to the equitable doctrine of specific performance in ch 3 at 114. 81 William Macready, quoted by Henry Irving in an address to the students of Harvard University, 1885 (The Drama: Addresses by Henry Irving (London, William Heinemann, 1893). Cited in JR Brown, Shakespeare’s Plays in Performance (London, Edward Arnold, 1966) 53. See generally, ch IV, ‘Subtext’. 82 Ephraim London was the first to offer the distinction between ‘The Law in Literature’ and ‘The Law as Literature’ as the titles to the two volumes of his anthology The World of Law (New York, Simon & Schuster, 1960). 83 See eg, R (on the application of Bancoult) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2008] UKHL 61; [2008] 3 WLR 955 (HL) para [151] (Lord Mance). 84 I Anstey, The Pleader’s Guide, A Didactic Poem etc (London, Cadell and Davies, 1810). 85 K Dolin, A Critical Introduction to Law and Literature (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007) 212. 86 See also, J Cole, ‘Thoughts from the Land of And’ (1988) 39 Mercer Law Review 907.

17

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 17 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 18 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009

Excursion concept of equity flies freely over the various fields of human thought.87 When it lands in a particular field, it is understood in the context of the field – the scholar of hermeneutics sees it as a way of reading, the scholar of rhetoric sees it as a way of speaking, and so on. Its meaning is always contextual in this sense, but the reader who has the imagination to move between the fields will begin to suspect that equity is essentially the same in each place. The cage in the image represents the confines of the regular rules of law. English law, and the Court of Chancery especially, has appropriated equity as if it were asserting that ancient right to appropriate res natura which Justinian described in his Institutes: Wild animals, birds, and fish, that is to say all the creatures which the land, the sea, and the sky produce, as soon as they are caught by any one become at once the property of their captor by the law of nations; for natural reason admits the title of the first occupant to that which previously had no owner.88

Where did English law find the idea of equity? Perrault’s tale of The Sleeping Beauty provides a visual clue. When the King and his council are under the spell of a magical sleep, we are told that ‘between the spectacles on the Archbishop’s nose and the spectacles on the Lord Chancellor’s a spider has spun a beautiful web’.89 The web of equity in the Lord Chancellor’s Court of Chancery was spun out of an ecclesiastic concern for conscience, and interwoven with the concept of epieikeia borrowed from Aristotle. Chancery’s trespass into the fields of theology and classical philosophy proved no bar to chancery’s appropriation of the idea of equity. Even this is consistent with Justinian’s Institutes: So far as the occupant’s title is concerned, it is immaterial whether it is on his own land or on that of another that he catches wild animals or birds.90

The English legal system has captured equity and turned it into ‘a reasonable measure, containing in it selfe a fit proportion of rigor . . .a ruled kind of Justice’,91 but how are we to prevent it from becoming all rules and no justice? There is a humane temptation to let the legal idea live more freely – to allow greater innovation and flexibility – but the risk is that the bird will fly out of sight. Justinian’s Institutes make it clear that if this happens, the appropriated bird regains its wild status.92 In chapter three, I will identify a possible compromise

87 Mark Fortier pursues the peregrine idea of equity across various fields in his book The Culture of Equity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2005). 88 Imperatoris Iustiniani Institutionum 2.1.12 (trans JB Moyle) (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1913). See generally, G McLeod, ‘Wild and Tame Animals and Birds in Roman law’ in P Birks (ed), New Perspectives in the Roman Law of Property: Essays for Barry Nicholas (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1989) 169–76. 89 The Sleeping Beauty and Other Fairy Tales from the Old French retold by Sir Arthur QuillerCouch, above n 6 at 19. 90 Above n 88. 91 W West, The Second Part of Symboleography (1594) references are to the popular 1641 edition (London, Miles Flesher and Robert Young, 1641) 174, section 3. 92 Above n 88.

18

Columns Design Ltd

/

Job: Watt

/

Division: Chap01

/Pg. Position: 18 /

Date: 14/5

JOBNAME: Watt PAGE: 19 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Mon Jun 29 10:45:03 2009