Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World: Studies in Honour of Matthew Freeman Trundle 1350283800, 9781350283800

"Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World offers eleven papers analysing the processes, consequences and probl

113 20 22MB

English Pages [305] Year 2024

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Cover

Halftitle page

Series page

Title page

Copyright page

CONTENTS

FIGURES

TABLES

CONTRIBUTORS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

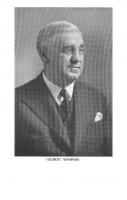

IN MEMORIAM MATTHEW FREEMAN TRUNDLE

12 October 1965 – 12 July 2019

Selected publications of Matthew Trundle

CHAPTER 1 MONEY, POWER AND THE LEGACY OF MATTHEW TRUNDLE IN ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy and David Rosenbloom

Case studies

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 2 THE UPKEEP OF EMPIRE: COSTS AND RATIONS Anthony Spalinger

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 3 PIETY, MONEY AND COINAGE IN GREEK RELIGION Matthew Trundle

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 4 NAVAL SERVICE AND POLITICAL POWER IN CLASSICAL ATHENS: AN INVERSE RELATION David Rosenbloom

Socio-economic class and military service

Misthophora for jury service

The ratio of military to jury pay: Maintaining military advantage

Naval service, migration and economic opportunity

A significant minority: Athenian the¯tes in the navy during their political ascendance

Naval service and political power

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 5 THE PERILS OF VICTORY: SPARTA’S UNEASY RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PROFITS OF WAR Ellen Millender

Pausanias and the perils of Plataea

Agesilaus II and the political benefi ts (or dangers?) of booty

Brasidas, Gylippus and Lysander: The hazards of victory and hegemony

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 6 PEGASI AND WAR: PATTERNS OF MINTING AT CORINTH IN THE LATER FOURTH CENTURY bce Lee L. Brice

Why strike coins?

Corinth: A case study

Conclusions

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 7 THE WAGE COST OF ALEXANDER’S PIKE-PHALANX Christopher Matthew

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 8 SICILY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN c. 540-31 bce: EVIDENCE FROM COIN CIRCULATION Christopher de Lisle

Methodological issues and limitations

Findings

Conclusions

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 9 RRC 1/1: THE FIRST STRUCK COIN FOR THE ROMANS Kenneth A. Sheedy

Addendum

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 10 THE MILITARY HISTORY OF EARLY ROMAN COINAGE Jeremy Armstrong and Marleen K. Termeer

The military context of early Roman coinage

Early coin production by Rome and the allies

Rome’s military economy

The Mediterranean military economy c . 300

Conclusions

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 11 CORRUPTION, POWER AND AN ORACLE IN THE LATE ROMAN REPUBLIC: THE RESTORATION OF PTOLEMY AULETES John Rich

Recognition and flight

Lentulus Spinther’s assignment

The oracle

Impasse

Restoration and aftermath

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 12 MONEY AND WEALTH IN TACITUS Arthur J. Pomeroy

Notes

Bibliography

CHAPTER 13 GOTHIC MERCENARIES Daniel K. Knox

The difficulty of identifying mercenaries

Conditions for mercenary service in Late Antiquit

Defining mercenary service

Gothic mercenaries in the late fifth century

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

INDEX

Citation preview

MONEY, WARFARE AND POWER IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

i

Also available from Bloomsbury A CULTURAL HISTORY OF MONEY IN ANTIQUITY edited by Stefan Krmnicek GREEK WARFARE: MYTH AND REALITIES by Hans van Wees SHIPS AND SILVER, TAXES AND TRIBUTE: A FISCAL HISTORY OF ARCHAIC ATHENS by Hans van Wees WAR AS SPECTACLE: ANCIENT AND MODERN PERSPECTIVES ON THE DISPLAY OF ARMED CONFLICT edited by Anastasia Bakogianni and Valerie M. Hope

ii

MONEY, WARFARE AND POWER IN THE ANCIENT WORLD: STUDIES IN HONOUR OF MATTHEW FREEMAN TRUNDLE

Edited by Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy and David Rosenbloom

iii

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2024 Copyright © Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy, David Rosenbloom and Contributors, 2024 Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy, David Rosenbloom and Contributors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on p. xi constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover image: Silver tetradrachm of Ptolemy I, struck in the name of Alexander IV, depicting Athena marching, verso. 4th century BC . Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rosenbloom, David Scott, editor. | Pomeroy, Arthur John, 1953- editor. | Armstrong, Jeremy, editor. | Trundle, Matthew, 1965-2019, honoree. Title: Money, warfare and power in the ancient world : studies in honour of Matthew Freeman Trundle / edited by David Rosenbloom, Arthur J. Pomeroy, Jeremy Armstrong. Description: London ; New York, NY : Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2023028745 (print) | LCCN 2023028746 (ebook) | ISBN 9781350283763 (hardback) | ISBN 9781350283800 (paperback) | ISBN 9781350283770 (pdf) | ISBN 9781350283787 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: War--Economic aspects--Rome. | War--Economic aspects--Greece. | War, Cost of. | Coinage--Rome. | Coinage--Greece. | Military history, Ancient. | Rome--Economic conditions--510-30 B.C. | Greece--Economic conditions--To 146 B.C. | Trundle, Matthew, 1965-2019. Classification: LCC HB195 .M58 2024 (print) | LCC HB195 (ebook) | DDC 330.938--dc23/eng/20230712 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023028745 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023028746 ISBN:

HB: 978-1-3502-8376-3 ePDF: 978-1-3502-8377-0 eBook: 978-1-3502-8378-7

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

iv

CONTENTS

List of Figures List of Tables List of Contributors Acknowledgements Abbreviations In Memoriam, Matthew Freeman Trundle 1

Money, Power and the Legacy of Matthew Trundle in Ancient Mediterranean Studies Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy and David Rosenbloom

vi vii viii xi xii xiii

1

2

The Upkeep of Empire: Costs and Rations Anthony Spalinger

11

3

Piety, Money and Coinage in Greek Religion Matthew Trundle †

29

4

Naval Service and Political Power in Classical Athens: An Inverse Relation David Rosenbloom

45

The Perils of Victory: Sparta’s Uneasy Relationship with the Profits of War Ellen Millender

73

5 6

Pegasi and War: Patterns of Minting at Corinth in the Later Fourth Century bce Lee L. Brice

105

7

The Wage Cost of Alexander’s Pike-Phalanx Christopher Matthew

127

8

Sicily in the Mediterranean c. 540–31 bce: Evidence from Coin Circulation Christopher de Lisle

145

RRC 1/1: The First Struck Coin for the Romans Kenneth A. Sheedy, with an Addendum by Michael Rampe

175

9

10 The Military History of Early Roman Coinage Jeremy Armstrong and Marleen K. Termeer

197

11 Corruption, Power and an Oracle in the Late Roman Republic: The Restoration of Ptolemy Auletes John Rich

219

12 Money and Wealth in Tacitus Arthur J. Pomeroy

245

13 Gothic Mercenaries Daniel K. Knox

259

Index

279 v

FIGURES

8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7

vi

Finds of Syracusan coinage minted in Period III Hoard finds in Sicily by period deposited All external coinage in Period IV hoards Findspots of Campanian coinage minted in the First Punic War Roman coins in Sicilian hoards of Period VI Non-Sicilian coin finds at Morgantina and Monte Iato by minting date Sicilian coin finds in Gaul and Illyria, by date of minting (top) and deposit (bottom) Distribution of Sicilian coinage abroad by period minted (left) and deposited (right) Sources of coinage deposited in Sicily, by period of deposition ACANS inv. 07GS16. RRC 1/1. Mint: Neapolis. 3.16g. Left panel: Obverse. Right panel: Reverse Overlay of ACANS inv. 07GS16 and Glasgow, Hunterian Mus. 151 Glasgow, Hunterian Mus. 151. RRC 1/1. Mint: Neapolis. 3.11g. Top panel: Obverse. Bottom panel: Reverse ACANS inv. 07GS117. Mint: Neapolis. 6.51g. Left panel: Obverse. Right panel: Reverse ACANS inv. 07GS121. Mint: Neapolis. 3.71g. Left panel: Obverse. Right panel: Reverse ACANS inv. 07GS36. Mint: Cales. 6.95g. Left panel: Obverse. Right panel: Reverse ACANS inv.07GS16. 3D model using a photogrammetry approach

151 153 154 157 159 161 162 164 166 175 179 180 184 184 185 191

TABLES

2.1 2.2 6.1 7.1 7.2 7.3 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4

Provisioning of soldiers, based on P. Anastasi I Daily calorific value of provisions as estimated by Heagren (2012, 169–72) Number of control marks in each series of Ravel Period Five staters The sub-units of the pike-phalanx The structure of a file of the pike-phalanx The monthly and annual wages of a file of the pike-phalanx CH 8.35 (‘Selinunte 1985’) Sicilian coins in western Mediterranean hoards, Period II Sicilian coins in eastern Mediterranean hoards, Period II Sicilian hoards containing eastern Mediterranean coins, Period III Macedonian coins in Sicilian hoards Hoards containing Roman coins minted in Sicily in Period VI RRC 1/1 Taliercio Mensitieri (1986) phase I Taliercio Mensitieri (1986) phase I, group Ic Bronze unit issues with obverse head of Apollo/ reverse man-headed bull

16 17 115 134 135 137 147 148 149 150 154 160 178 182 182 187

vii

CONTRIBUTORS

Jeremy Armstrong is Associate Professor of Ancient History at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He received his BA from the University of New Mexico and his MLitt and PhD from the University of St Andrews. He works primarily on archaic central Italy, and most specifically on early Roman warfare. He is the author of War and Society in Early Rome: From Warlords to Generals (2016) and the editor/co-editor of a number of volumes on ancient warfare. He was a friend, collaborator and colleague of Matthew Trundle at the University of Auckland. Lee L. Brice is Distinguished University Professor in the Department of History at Western Illinois University. He has published seven books on ancient history including most recently People and Institutions in the Roman Empire, coedited with Matthew Trundle and Andrea Gatzke. His articles and chapters address Corinthian coinage, mutiny, ancient military history, pedagogy and the Roman army on film. He is the series editor of Warfare in the Ancient Mediterranean World and senior editor of the series Research Perspectives: Ancient History. He initially met Matthew over a decade ago through Garrett Fagan and formed a fast friendship that resulted in several collaborations and much fun. Christopher de Lisle has been Assistant Professor of Greek History at the University of Durham since 2021. His doctoral thesis, completed at Oxford (2013–17), was published as Agathokles of Syracuse: Sicilian Tyrant and Hellenistic King (2021). He was a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at University College, Oxford (2017–21). He was taught by Matthew Trundle as an undergraduate at Victoria University of Wellington (2008–10) and abandoned a law degree in order to take his Honours course in 2011. Daniel K. Knox is a PhD candidate in the Department of Medieval Studies at Central European University in Vienna. His PhD research is focused on the contested papal election of ad 498 and the subsequent ‘Laurentian Schism’ that erupted in Rome in the first decade of the sixth century. Between 2019 and 2022 he was an assistant professor (Prae-doc) in the History Faculty at the University of Vienna where he taught classes in late antique social media and digital humanities. Daniel first met Matthew during his graduate studies at Victoria University of Wellington, when, along with David Rosenbloom, Matthew led a group of Classics students on a six-week field trip to Greece. He subsequently followed Matthew to the University of Auckland, where Matthew became not only a cherished mentor, but a true friend. Daniel would not be where he is today without Matthew’s guidance. Christopher Matthew is Lecturer in Ancient History at the Australian Catholic University in Sydney. After first meeting at a conference, Christopher remained a friend viii

Contributors

and research collaborator with Matthew Trundle for many years, and the two would often workshop ideas, review drafts of each other’s work, and engage in the collegial debates and discussions for which Matthew was well known, and well respected. The author of several books and articles on various topics of ancient warfare, Christopher teaches units on the Ancient Near East, the Roman Republic, the Greek City-States, Pompeii and Greek Drama. Ellen Millender is the Omar and Althea Hoskins Professor of Greek, Latin and Ancient Mediterranean Studies and Humanities at Reed College, Oregon, USA. She has published on many aspects of Spartan society, including literacy, kingship, military organization, women and leadership. Forthcoming publications address Spartan austerity, Xenophon’s treatments of Spartan obedience and emotional practices, and the role of both spectacle and performance in Xenophon’s accounts of Sparta. Professor Millender is also completing a monograph on the Athenians’ construction of Spartan ‘otherness’. She frequently collaborated with her dear friend, Matthew Trundle, on ancient history panels and greatly misses their exchange of ideas. Arthur J. Pomeroy is Professor Emeritus of Classics at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. His research interests include Roman social history, Roman historiography, and the depiction of ancient Greece and Rome in film and television. He has published a number of chapters and articles on the Roman historian, Tacitus, while his most recent book is A Companion to Greece and Rome on Screen (2017). He was a colleague of Matthew Trundle during his time teaching at Victoria University of Wellington. John Rich is Emeritus Professor of Roman History at the University of Nottingham, where he taught throughout his career. He has published widely on Roman history and historiography, and in particular on Roman war and imperialism, the reign of Augustus, and the historian Cassius Dio, and was a contributor and editorial board member for The Fragments of the Roman Historians (gen. ed. T. J. Cornell, 2013). Along with his colleague, the late Wolfgang Liebeschuetz, John Rich taught Matthew Trundle ancient history throughout his undergraduate years at the University of Nottingham (1984–87). David Rosenbloom is Professor and Chair of the Ancient Studies Department at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. He is the author of Aeschylus: Persians (2006) and co-editor (with John Davidson) of Greek Drama IV: Texts, Contexts, Performance (2012). He has published numerous articles and chapters on Greek tragedy, comedy, history and rhetoric. He was Matthew Trundle’s colleague in the Classics Department of Victoria University of Wellington from 1999–2011 and will always cherish memories of co-teaching and travelling with him throughout Greece – from Komos, Crete to Delphi and all points between – over six-week periods in 2001, 2007 and 2010. Kenneth A. Sheedy is Associate Professor at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. He is the founding director of the Australian Centre for Ancient Numismatic Studies (from 2000). He is also a member of the teaching staff of the Department of History and Archaeology. He was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in ix

Contributors

2010 and is the representative of the Academy for the SNG Australia Project at the Union Académique Internationale. Matthew Trundle was a visiting scholar at ACANS. Anthony Spalinger is Emeritus Professor of Ancient History (Egyptology) at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. His research interests include the art of war in the ancient world, ancient Egyptian calendrics, the ancient economy of Egypt, and narrative in Egyptian art. His most recent book is The Books Behind the Mask (2022), a study of the narrative structures employed in the monumental inscriptions of the military pharaohs. He was a colleague of and co-lecturer in ancient military history with Matthew Trundle during his time at the University of Auckland. Marleen K. Termeer is Assistant Professor in Ancient History at the Radboud Institute for Culture and History (Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Her research focuses on Roman expansion in the Republican period, and cultural interaction between Rome and other players in Italy and the Mediterranean. Her current project Coining Roman Rule? (NWO Veni 016.Veni.195.134) examines the introduction of coinage in the Roman world as part of these broader dynamics. Matthew Trundle’s work on mercenaries and mobility has been inspirational in this context. Matthew Trundle † was Professor of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Auckland. His research interests were primarily in the field of ancient Greek history, and he was the author of Greek Mercenaries from the Late Archaic Period to Alexander (2004), and the editor of a number of volumes including New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare (2010), Beyond the Gates of Fire: New Perspectives on the Battle of Thermopylae (2013) and Brill’s Companion to Sieges in the Ancient Mediterranean (2019). He died on 12 July 2019, after a battle with Acute Lymphoid Leukaemia.

x

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This volume was produced during a very difficult period, between 2020 and 2023, marked by the Covid-19 pandemic. Indeed, as editors, we often wondered what Matthew Trundle would have thought about the pandemic and the varied responses to it worldwide. However, we know he would have been deeply touched by the effort and dedication that the contributors to this volume demonstrated in producing and revising their chapters under such trying circumstances. As a result, our first thanks must be to them. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful suggestions in improving the manuscript and the School of Humanities at the University of Auckland for providing the generous subvention which allowed this volume to be published. Many thanks must also go to Francesca Taylor, whose editorial assistance vastly improved the final product. Thanks should go, as well, to Lily Mac Mahon and Zoë Osman at Bloomsbury for their work and support in bringing this volume to fruition. Finally, we must also thank Matthew Trundle himself, to whom this volume is dedicated, for his friendship, scholarship, and his boundless enthusiasm for the subject that inspired this volume. He made us all better scholars, and better people, and the world is a poorer place without him. Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy and David Rosenbloom

xi

ABBREVIATIONS

Ancient abbreviations generally follow those in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th edition. Modern bibliography abbreviations follow those in l’Année philologique. ACANS

Australian Centre for Ancient Numismatic Studies

AIO

Attic Inscriptions Online (http://www.atticinscriptions.com/)

CH

Price, M. J., et al (1975–), Coin Hoards. London and Leuven: Royal Numismatic Society and Peeters.

CID

Rougement G., ed. (1977), Corpus des inscriptions de Delphes, Vol. I, Lois sacrées et règlements religieux. Paris and Athens: De Boccard, École française d’Athènes.

HNItaly

Rutter, K. and A. Burnett (2001), Historia Numorum: Italy, London: British Museum Press.

IGCH

Thompson, M., O. Mørkholm, and C. Kraay (1973), Inventory of Greek Coin Hoards, New York: American Numismatic Society.

KRI

Kitchen, K. (1968–90), Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical, Oxford: Blackwell.

OLD

Glare, P. G. W., ed. (2012), Oxford Latin Dictionary, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

RRCH

Crawford, M. (1969), Roman Republican Coin Hoards, London: Royal Numismatic Society.

Urk.

Sethe, K. and H. Helck (1903–61), Urkunden des Ägyptischen Altertums, Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung.

xii

IN MEMORIAM MATTHEW FREEMAN TRUNDLE

12 October 1965 – 12 July 2019 Matthew Trundle will be remembered as a kind and charismatic figure, as well as an astute scholar, who worked ceaselessly to popularize Classics in the United Kingdom and Ireland, in North America, and in Australasia. In particular, he made major contributions to the study of warfare in the Greek and Roman worlds and, in association with the payment of mercenaries, the role of money in ancient societies. xiii

In Memoriam, Matthew Freeman Trundle

Matthew was born in London and graduated with a BA from the University of Nottingham in 1987, with joint Honours in Ancient History and History. He then moved to McMaster University in Canada, first gaining an MA and then, in 1996, completing a PhD thesis, entitled ‘The Classical Greek Mercenary and His Relation to the Polis’, under the supervision of Daniel Geagan. In 1999 he was appointed lecturer in Classics at the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand and rapidly rose to Associate Professor in Classics and Associate Dean (Humanities and Social Sciences), before being appointed Professor of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Auckland in 2012. Matthew often recalled that Xenophon’s narrative of the adventures of the Greek mercenaries fighting their way back home from Persia in the Anabasis inspired his interest in Classics. It is perhaps unsurprising then that his first major publication was Greek Mercenaries: From the Late Archaic Period to Alexander (2004) and, in association with fellow McMaster graduate Garrett Fagan, he organized a joint APA/AIA panel in 2008 that formed the basis for the edited volume New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare (2010). At the time of his death, he was working on a monograph on the interconnection of coinage and warfare in the Greek and Hellenistic worlds, as well as completing the compilation of inscriptions found during excavations at Isthmia that Daniel Geagan had entrusted to him. Sadly, before he completed these projects, Matthew died from leukaemia in Wellington on 12 July 2019. Matthew will be remembered among his colleagues and students for his caring and selfless nature, always seeing and seeking the best in those around him. The first to buy a round of drinks, he was well known for his gregarious participation in the meetings of the major classical associations, including the Classical Association (UK), the American Philological Association (now Society for Classical Studies), the Classical Association of South Africa, and the Australasian Society for Classical Studies. He also presented papers at numerous universities around the world, including in China, South Korea and Japan. An outstanding teacher and dynamic public speaker, he was an untiring promoter of Classics wherever he went, not only encouraging undergraduates, secondary school teachers and colleagues in the tertiary system, but also generously devoting his time and attention to the wider community. Among his successful pupils, for instance, he numbered Victor Vito, All Black and Wellington Hurricanes rugby team captain. For some time, he was a regular guest on Kim Hill’s Saturday Morning programme on Radio New Zealand, sharing his knowledge of the ancient world with listeners throughout the country. He also regularly submitted opinion pieces to The New Zealand Herald and other local print media, often offering political commentary using ancient parallels. Proud of his blue-collar roots and a vocal Labour supporter, both in New Zealand and the United Kingdom, Matthew argued strongly for the importance of a dynamic and inclusive democracy. The principles that Matthew taught in the classroom as being central to life in the ancient Greek polis, isonomia (ἰσονομία, ‘equality before the law’) and isēgoria (ἰσηγορία, ‘equality in speech’), were also central to his approach to modern society and politics. xiv

In Memoriam, Matthew Freeman Trundle

A father to Christian, husband to Catherine, and dear friend to many, he is deeply missed. In his honour, the University of Auckland has established an endowment to fund a biennial lecture in Classics at Auckland and Wellington. ὣς σὺ μὲν οὐδὲ θανὼν ὄνομ᾽ ὤλεσας, ἀλλά τοι αἰεὶ πάντας ἐπ᾽ ἀνθρώπους κλέος ἔσσεται ἐσθλόν . . . Selected publications of Matthew Trundle ●

(1998), ‘Epikouroi, Xenoi and Misthophoroi in the Ancient Greek World’, War and Society 16: 1–12.

●

(1999), ‘Identity and Community Among Greek Mercenaries in the Classical World: 700–323 bce ’, Ancient History Bulletin 13: 28–38. [Repr. in Wheeler, E. (ed.) (2007), The Armies of Classical Greece, 481–92, Aldershot: Ashgate]

●

(2001), ‘The Spartan Revolution: Hoplite Warfare in the Late Archaic Period’, War and Society 19: 1–18.

●

(2003), ‘Camilla and The Volscians: Historical Images in Aeneid 11’, in J. Davidson and A. Pomeroy (eds), Theatres of Action, 164–85, Auckland: Polygraphia. Prudentia Supplement.

●

(2004), Greek Mercenaries: From the Late Archaic to Alexander, London: Routledge.

●

(2006), ‘Money and the Great Man in the Fourth Century bce : Military Power, Aristocratic Connections and Mercenary Service’, in S. Lewis (ed.), Ancient Tyranny, 65–76, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

●

(2008), ‘OGIS 1.266: Kings and Contracts in the Hellenistic World’, in P. McKechnie and P. Guillaume (eds), Ptolemy Philadelphus and his World, 103–16, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2010), ‘Why Did Greeks and Romans Fight Wars?’, The Journal of Greco-Roman Studies 40: 37–56.

●

(ed. with G. Fagan) (2010), New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2010) ‘Introduction’ (with G. Fagan), in M. Trundle and G. Fagan (eds), New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, 1–19, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2010) ‘Coinage and the Transformation of Greek Warfare’, in M. Trundle and G. Fagan (eds), New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, 227–52, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2010), ‘Light Armed Troops in Classical Athens’, in D. Pritchard (ed.), War, Culture and Democracy in Classical Athens: 139–60, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

●

(2012), ‘Greek Athletes and Warfare in the Classical Period’, Nikephoros: Zeitschrift für Sport und Kultur im Altertum 25: 221–37.

xv

In Memoriam, Matthew Freeman Trundle

xvi

●

(ed. with C. Matthew) (2013), Beyond the Gates of Fire: New Perspectives on the Battle of Thermopylae, Bradford: Pen and Sword.

●

(2013), ‘Thermopylae’, in C. Matthew and M. Trundle (eds), Beyond the Gates of Fire: New Perspectives on the Battle of Thermopylae, 27–38, Bradford: Pen and Sword.

●

(2013), ‘Conclusion: the Glorious Defeat’, in C. Matthew and M. Trundle (eds), Beyond the Gates of Fire: New Perspectives on the Battle of Thermopylae, 150–63, Bradford: Pen and Sword.

●

(2013), ‘Why Greek Tropaia?’, in J. Armstrong and A. Spalinger (eds), Rituals of Triumph, 123–38, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2013), ‘The Business of War: Professional Soldiers in Antiquity’, in B. Campbell and L. Tritle (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World, 407–41, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

●

(2016), ‘The Spartan Krypteia’, in G. Fagan and W. Riess (eds), The Topography of Violence in the Greco-Roman World, 60–76, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

●

(2016), ‘Coinage and the Economics of the Athenian Empire’, in J. Armstrong, (ed.), Circum Mare: Themes in Ancient Warfare, 65–79, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2017), ‘The Reception of the Classical Tradition in New Zealand War Reporting and Memory in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries’, in D. Burton, S. Perris and W. J. Tatum (eds), Athens to Aotearoa: Greece and Rome in New Zealand Literature and Society, 307–19, Wellington: Victoria University Press.

●

(2017), ‘Spartan Responses to Defeat: From a Mythical Hysiae to a Very Real Sallassia’, in J. H. Clark and B. Turner (eds), Brill’s Companion to Military Defeat in Ancient Mediterranean Society, 144–61, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2017), ‘Greek Historical Influence on Early Roman History’, Antichthon 51: 21–32.

●

(2017), ‘Hiring Mercenaries in the Classical Greek World. Causes and Outcomes’, Millars 43.2: 35–61.

●

(2017), ‘Coinage and Democracy: Economic Redistribution as the Basis of Democratic Athens’, in R. Evans (ed.), Mass and Elite in the Greek and Roman Worlds: From Sparta to Late Antiquity, 11–20, London: Routledge.

●

(2017), ‘The Anabasis 401–399 bc’, ‘The Corinthian War 395–388 bc’, ‘Fourth Century bc Greek Wars’, ‘Carthaginian Offensives in Sicily, 409–307 bc’, in M. Whitby and H. Sidebottom (eds), The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Battles vol. III, 13: 1–9, 14: 1–11, 15: 1–5, 16: 1–14, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

●

(2018), ‘The Role of Religion in Declarations of War in Archaic and Classical Greece’, in M. Dillon, C. Matthew and M. Schmitz (eds), Religion and Classical Warfare Volume 1: Ancient Greece, 24–33, 212–14, Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

In Memoriam, Matthew Freeman Trundle ●

(2018), ‘War and Society in the Ancient Mediterranean’, in M. S. Muehlbauer and D. J. Ulbrich (eds), The Routledge History of Global War and Society, 79–91, London: Routledge.

●

(2018), ‘The Pinker Thesis: Were There Angels of a Better Nature in Ancient Greece?’, Historical Reflections / Reflexions Historique 44: 17–28.

●

(ed. with J. Armstrong) (2019), Brill’s Companion to Sieges in the Ancient Mediterranean, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2019), ‘Sieges in the Mediterranean World’, in J. Armstrong and M. Trundle (eds), Brill’s Companion to Sieges in the Ancient Mediterranean, 1–17, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2019), ‘The Introduction of Siege Technology into Classical Greece’, in J. Armstrong and M. Trundle (eds), Brill’s Companion to Sieges in the Ancient Mediterranean, 135–49, Leiden: Brill.

●

(2019), ‘The Limits of Nationalism: Brigandage: Piracy and Mercenary Service in Fourth Century bce Athens’, in R. Evans and M. De Marre (eds), Piracy, Pillage and Plunder, 25–37, London: Routledge.

●

(ed. with A. Gatzke and L. L. Brice) (2020), People and Institutions in the Roman Empire: Essays in Memory of Garrett G. Fagan, Leiden: Brill.

●

(ed. with G. Fagan, L. Fibiger, and M. Hudson) (2020), The Cambridge World History of Violence, vol. I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

●

(2020), ‘Violence, Law and Community’, in G. Fagan, L. Fibiger, M. Hudson and M. Trundle (eds), The Cambridge World History of Violence, vol. I, 533–49, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

xvii

xviii

CHAPTER 1 MONEY, POWER AND THE LEGACY OF MATTHEW TRUNDLE IN ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES Jeremy Armstrong, Arthur J. Pomeroy and David Rosenbloom

. . . the sinews of war are limitless money . . . . . . nervos belli pecuniam infinitam . . . Cicero, Philippics, 5.2.5. At the time of his death, Matthew Trundle was working on a monograph investigating the relationship between money and military action from early Greece to Alexander the Great and his successors. This had long been an area of interest for him, but was something to which he had begun to devote significant attention from 2016 on, as he attempted to summarize and synthesize his thoughts on the wider phenomenon. Sadly, that volume remained unfinished, although one relatively complete chapter (subsequently edited by Christopher de Lisle) can be found in this collection. The chapters in this volume, however, continue in the broad vein Matthew had started to mine, exploring multiple relationships between money, war and political power – both personal and collective – in the ancient Mediterranean world and indeed extending the scope to include different cultures and socio-political systems, ranging from Pharaonic Egypt to late antique Europe. Contributed by friends and colleagues of Matthew, they are a testament to his influence on scholarship and a scholarly conversation that covers the breadth of antiquity. While obviously both warfare and forms of currency existed before the Lydian introduction of coinage in the late seventh century bce ,1 the widespread adoption and use of coined money by the mid-fifth century in (especially Greek-speaking) communities throughout the Mediterranean marked a watershed moment in that it enabled the accumulation and easy transfer of wealth in ways that made it both an instrument and an aim of warfare.2 It facilitated military networks, allowing both states and individual military leaders to harness manpower and resources, from across a wide region, using an increasingly universal and accepted method of exactly quantifying wealth. As suggested by Cicero in the quotation at the outset of this chapter, coinage quickly became one of the most prominent physical manifestations of the multivariate connections, or sinews, which bound ancient militaries together. In the eastern Mediterranean, the monetization of warfare eventually subsumed the ‘citizen soldier’ and ‘mercenary’ under a single rubric: the professional soldier.3 Matthew’s work often strove to unify the social and economic systems that crisscrossed the ancient Mediterranean basin. In doing so, one of his key contributions was to 1

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

emphasize how ancient mercenary service relied, first and foremost, on social bonds – the economic connections were secondary.4 Although often defined by (and derided for) being soldiers for hire, the simple pursuit of wealth was not a mercenary’s only, or even primary, aim. His was not a world driven by money; however, it may have been a world increasingly shaped by money. The spread of coinage across the Mediterranean, often through mercenaries and other military expenses, fundamentally changed the nature of both warfare and society in the region. While more social military pursuits, such as seeking timē (honour) and displaying virtus (manliness), remained intact, leaders also needed to consider this new physical manifestation of (economic) power. A state or war leader could not be successful without access to coined money. Aristotle’s concept of warfare as a natural art of acquisition seems to be tailor-made for the insights of New Institutional Economics (NIE), an approach to the history of economics based on the work of Douglass North in which the ‘structure’ – institutions, technology, demography and ideology of a society – determine the ‘performance’ of an economy, quantified by measures such as volume and stability of production, allocation of benefits and costs, gross domestic product, per capita income, and so on.5 Some historians have come to see warfare and its putative objective, ‘empire’, as the preeminent mechanism for mobilizing ‘the economic resources of the Mediterranean’.6 It must be noted, however, that Matthew never fully subscribed to this sort of model. His economic systems were more embedded and shaped as much by concepts like ‘positive reciprocity’ as they were by economic theory.7 However, as Matthew also recognized, the simple economic aspects, which form the grist for NIE’s mill, cannot be ignored. Warfare was the dominant coinage-intensive activity in ancient Mediterranean societies; it commanded the most manpower and marshalled the most resources; it posed the greatest risks and promised the highest rewards. The difference between victory and defeat in battle – life or death, freedom or slavery, flourishing or blight, glory or shame – was the sharpest stimulus to the production, allocation and distribution of private and collective resources in the ancient Mediterranean. Thucydides, the earliest exponent of the nexus of money, military domination and political power in the evolution of the polis and the formation of empires,8 understood the acquisition of power over other cities as a derivative of ‘a surplus of money’ (periousian chrēmatōn, 1.2.2; cf. Arist. EN 1119b27).9 Powerful agents parlayed such surpluses into spheres of domination cemented by a mutual desire for gain: ‘desiring profit (tōn kerdōn), the weaker accept servitude (douleia) to the more powerful and the more powerful, having surpluses, acquire the weaker cities as subjects’ (Thuc. 1.8.3). In prehistory, Thucydides suggested Minos and Agamemnon gained surpluses, developed naval power, controlled islands and coastal populations, reduced piracy and brigandage, and diverted the gains of vanquished marauders to themselves (Thuc. 1.4, 7–8, 9–11). Populations settled closer to the sea, exploited its resources, secured surpluses of money, built fortifications and occupied isthmuses ‘for the sake of seaborne commerce’ and ‘to win advantage over their neighbours’ (Thuc. 1.7.1). In Thucydides’ scheme, Athens represents the culmination of the process of seeking to maximize collective wealth and to parlay it into supremacy over others. 2

Money, Power and Legacy

However, as Matthew identified, this process was incredibly dynamic and not nearly as straightforward as one might initially suppose. As he argued in 2011, while coined money was essential to the growth of Athenian naval power in the fifth century bce , the financial structures of the Athenian ‘empire’ seem to have been more geared toward redistribution than accumulation, especially during the Peloponnesian War, when Athens paid a premium for rowers and hoplites.10 As quickly as wealth flowed in from allied states and other sources, it often flowed out to misthophoroi (mercenaries) as chrēmata (coined money) just as quickly. Indeed, warfare suddenly appeared to be more about spending money than acquiring it, although the two remained linked. But as Matthew suggested, ‘Xenophon (An. 7.1.27) estimated that the total annual revenue of the Athenian empire in 431 bce was 1,000 talents. The siege of Potidaea, from which Athens derived little compensation, may have cost as much as 2,000 talents (Thuc. 2.70.2; Isoc. 15.113). We can guess that the costs of the Sicilian expedition were enormous, running to at least 150 talents per month for the fleet, crews and army’.11 Money was a tool to be used; war was an investment for future gain. More than any other collective activity, ancient warfare demanded coinage and observed no limit in securing sources for it. Even one of the kings of (supposedly) moneyless Sparta, Archidamus, understood that, ‘War is not a matter of arms more than it is a matter of the expenditure that advantages arms’ (Thuc. 1.83.2). He was aware that the Peloponnesians would need money and naval power to fight a war against Athens either ‘to be overpowering with ships’ or ‘to deprive the city of the revenue that supports its naval power’. He planned to obtain money and naval power through alliances with Greeks and ‘barbarians’ (Thuc. 1.82.2).12 Only in the case of wartime finance did individuals or cities consider using temple treasuries. The Corinthians talked of borrowing from treasuries at Delphi and Olympia to lure rowers away from Athens (Thuc. 1.121.3),13 an expedient that probably never materialized but cannot be entirely ruled out.14 On the other side, Pericles allayed Athenian anxieties by listing the financial resources at their disposal, which included gold and silver bullion in private and public dedications, sacred implements for processions and competitions, Persian spoils and wealth of this kind, valued at greater or equal to 500 talents (Thuc. 2.14.4). Pericles factored in the resources from other temples. If the Athenians had no other recourse, they could strip the gold leaf from Athena’s chryselephantine statue – 40 talents of refined gold; although they were obligated to pay it back (Thuc. 2.13.5). When push came to shove, nothing was off limits. Indeed, while the Athenians were not driven to such measures by the Peloponnesian War, when Athens was besieged by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 295 bce , the general Lachares did eventually resort to this.15 The Athenians borrowed around 6,000 talents from the treasury of the other gods during the Archidamian War.16 When they became desperate, they melted down golden Nikai from the Parthenon for coinage. According to Diodorus, Phocian generals coined more than 10,000 silver talents out of Delphi’s many treasuries, including Croesus’ dedications, to hire mercenaries for the Third Sacred War (Diod. Sic. 16.56.3–7; cf. 16.30). Cash-heavy armies were also magnets for merchants and markets; indeed, the formation of the latter was arguably a by-product of monetization accelerated by the 3

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

introduction of coinage. Thucydides identifies the deficiency of the Greek mobilization in the Trojan War as ‘not so much a scarcity of men as a lack of money’ (Thuc. 1.11.1) that prevented the full deployment of Agamemnon’s military forces. As Matthew noted, ‘coined money . . . enabled commanders not only to centralize supply redistribution, but also to attract suppliers to armies more effectively’.17 Already in Homer, after the completion of their defensive fortifications in Iliad 7, the Achaeans attracted the Lemnian merchant Euneus, son of Jason and Hypsipyle. The Achaeans bartered for wine in exchange for bronze, iron, hides, oxen and slaves (Il. 7.465–75).18 The lack of a single portable and fungible medium of exchange is a drag on market formation and hence military efficiency. Soldiers allocated the tasks of cultivating food and pillaging for booty – presumably, in Thucydides’ view, to barter for market supplies – did not participate in the fighting against Troy (Thuc. 1.11.1–2). It is not clear whether achrēmatia in this section means ‘lack of money’ (Thuc. 1.11.1–2) or ‘lack of resources’, for Thucydides wrote as if the Achaeans could have arrived at Troy with ‘an abundance of food’ (Thuc. 1.11.2),19 thereby obviating the need to commit troops to farming and pillaging and enabling them to take Troy in a shorter time with less effort (Thuc. 1.11.2). The supposed Achaean need to cultivate their own food (never mentioned in Homer) and to maraud for media of exchange to barter for food (likewise never mentioned) prevented Achaean power from reaching its potential.20 Moving from the epic to historical writing, we need not take Diodorus at his word – that the ‘market mob’ thronging around Agesilaus’ army in Ephesus ‘for the sake of booty’ was no less in number than his 4,400 hoplites and cavalry (Diod. Sic. 14.79.2; cf. Xen. Hell. 3.4.17 for Ephesus as a ‘workshop of war’) – to realize that armies drew sizeable markets for the major inputs and outputs of warfare – armaments, provisions and booty. Indeed, the conversion of the spoils of battle into coinage was a basic military function. Nicias raised 120 talents by selling war captives from Hyccara in Sicily in 415 bce (Thuc. 6.62.4). Livy claimed that, before the siege of Murgantia in 296 bce , Decius obliged his soldiers to sell booty to traders in order to attract a commercial following for his army during a run of siege and sack operations (Livy 10.16–17). Polybius reported that merchants acquired booty at prices below market value from Scipio’s forces late in the Second Punic War: soldiers anticipated expropriating even greater riches (Polyb. 14.7.1– 3). It has been suggested that booty from Syracuse and Capua was converted into the silver denarius coinage Rome first issued in 211/10 bce ;21 this was fed by gold donated to the treasury by senators and those who followed their lead (Livy 26.36.5–8) and specie from New Carthage, Tarentum and Metaurus.22 Thucydides realized that money was not tantamount to military and political power; it was only as good as the military capability – power (dynamis) – it could sustain. He imagined that future generations would think Sparta’s renown far surpassed its actual power if they formed their judgement from the building foundations of a deserted Sparta. The lack of expenditure on urban amenities obscures the fact that Sparta occupied two-fifths of the Peloponnese but held hegemony over the entire land mass and over allies outside of it (Thuc. 2.9.2–3). Sparta did not concentrate its population in an urban centre (or even define one by a peribolos wall); nor did it invest resources in spectacular 4

Money, Power and Legacy

temples and buildings, but ‘continued living in villages in the ancient Greek way’ (Thuc. 1.10.1–2). Thucydides believed that posterity would judge Athens to be twice as powerful as it actually was on the basis of its impressive buildings and temples (cf. Alcibiades on extravagant expenditure as a symbol that inflates Athens’ actual power, Thuc. 6.16.2). Money could buy spectacles of invincible power and even slavery (through tribute payments, Thuc. 1.121.5) more easily than it could buy actual power. Thucydides insisted on examining the powers (dynameis) of cities rather than their images (opseis) of power (Thuc. 1.10.3). Athens would be tempted, as Xerxes was in his invasion of Greece, to send a spectacle of invincible power to Sicily at an incalculable cost in money and lives (especially Thuc. 6.30–32).23 Thucydides’ narrative proceeds in stages toward the disastrous realization of the fallacy that money is power, a delusion akin to fallacious equations of money and wealth (Arist. Pol.1256a–58b)24 and of money and happiness (Hdt. 1.29–33). Kallet and Kroll put it succinctly, ‘whereas money made the Athenian empire, it would be money that would bring it down’.25 Thucydides’ analysis of Athens’ catastrophic misprision of money as power suggests that coined money functioned both as financial and cultural capital. Money paid for the buildings, festivals, rituals and performances that monumentalized and magnified Athenian power while connecting Athens’ subjects to the city as its ‘metropolis’ – it financed the acquisition of cultural capital. And because of the purity of its silver, the magnitude of its issues and the extent of its diffusion, the Athenian owl came to be viewed as quintessential coinage among ‘Greeks and barbarians alike’ (Ar. Ran. 717–35). Clare Rowan cogently argues that Roman coins were ‘monuments in miniature’ that ‘monumentalized contemporary events and ideas’.26 Athenian owls can also be considered monuments: silver embodiments of a virtually unchanging ideal of Athens as a victorious, powerful, wealthy, authoritative and trustworthy polis. Christopher Howgego has asked whether ‘the apparent neatness with which monetary systems fit the character of empires should cause us to question whether coinage has to some extent determined our own typology of empires’.27 The coinage of empires shows an awareness that money is power: not only is it expended for victory, but it also commemorates and glamourizes that victory as the possession of the Roman people, bearer of the epithets victor and invictus.28 Coinage is the means and end of victory, cyclically depleted and replenished; the coins themselves programmatically depict victory as the crowning glory of the city or of its personified representative, who himself becomes a divinity, displacing the gods of previous coinages. In sum then, and as Matthew clearly recognized and explained in his many works, coinage is key to untangling the tangled web of war, politics and socio-economics in the ancient Mediterranean, from the time of its introduction in sixth-century bce Lydia through the Roman period (and, indeed, after). These small artefacts, easily passed from hand to hand, were typically created for the express purpose of funding warfare and served as a proxy for, and physical embodiment of, the myriad connections and power dynamics which flowed through the region. While both war and coined currency could, and did, exist separately from each other, together they formed a potent combination, especially in highly competitive, multi-state contexts such as those of the Classical and Hellenistic periods. 5

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

Case studies The chapters of this volume comprise a range of case studies, which illuminate not only how powerful men and states used money and coinage to achieve their aims but how their aims and methods were often shaped by the medium of coined money – typically with unintended consequences. The volume begins with Anthony Spalinger’s exploration of how pre-monetized New Kingdom Egypt mobilized resources for a military venture far from home. Matthew Trundle’s contribution explores the monetization of piety, the uses of coinage in religious ritual and the role of temples as economic centres to argue that coinage opened up religion to outsiders and to new cults, democratizing and professionalizing religious practices – but also exposing them to new forms of ridicule. David Rosenbloom explores the inverse relation between rowing in the fleet for a wage and exercising power as paid juror and assemblymen among Athenian thētes as a factor in the evolution of Athens’ navy from a citizen-based organization to one manned increasingly by metics, mercenaries and slaves. Ellen Millender analyses the destabilizing effects of booty and money on the traditional politeia of Sparta during the course of the Peloponnesian War. Lee Brice questions the assumption that warfare and increased coining activity were directly related within the highly contested politics of Corinth in the late fourth century. Christopher Matthew tallies the costs of paying members of the pike phalanxes on the move and argues that the logistics of paying these troops at the rate of one talent per year affected the course of Alexander’s invasion of the Persian empire. Employing the largest database of coinage found in Sicily yet compiled, Christopher de Lisle charts the eventual entry of this silver-poor island into the economic networks of Rome and Carthage, which preferred bronze fiduciary coinages. Kenneth Sheedy shifts our view to the Roman world by re-examining the first known issue of struck Roman coinage (RRC 1/1), and points to the questionable role of these quarter units as symbols of an alliance between Rome and Neapolis. Jeremy Armstrong and Marleen Termeer further explore the origins of Roman coinage c. 300 bce , arguing that the move was part of a Roman strategy of cementing economic, political and (most importantly) military ties with monetized Italian allies. John Rich examines the opportunities for enrichment among leading Romans by supporting client kings, taking the restoration of Ptolemy Auletes in the late Republic and the surrounding intrigue as a test case. Arthur Pomeroy tries to make sense of Tacitus’ narrative of the credit and cash crisis in Annals 6.16–17. A story emerges of large-scale investment in loans and usury, contrary to aristocratic landed values, and of the Senate’s attempt at a solution that only exacerbates the problem. Tiberius’ temporary use of the public treasury to bail out debtors (many of whom were senators) hinges on questions of enforcement of regulations, both historical and renewed, in an atmosphere where fear predominates. Finally, building on Matthew Trundle’s conceptualization of the mercenary in the Classical period, Daniel Knox asks the question ‘were the Goths mercenaries?’ and explores the careers of Theodoric Strabo and Theodoric the Amal in an effort to understand the nature of the mercenary in sixth-century ce Europe. 6

Money, Power and Legacy

Although diverse in period and focus, the chapters in this volume are unified by their engagement with Matthew’s ideas and the core themes of his many scholarly works, a select list of which is printed at the end of the In Memoriam. Whether in the form of tokens of exchange or struck metal, coins allowed firmer economic ties between sectors of society. Mercenaries are the most obvious example of large-scale employment associated with an exchange that maintained its value over a wide geographic area. However, the usefulness of currency was also recognized in Mediterranean trade and assumed importance in allowing power to be projected over a wide geographical area. As Matthew recognized, wealth could help in creating empires and encouraging competition. It also, through bribery, encouraged self-interested behaviour that could hollow out states.

Notes 1. Schaps (2004), 34–92; Kroll (2012). 2. Trundle (2016), 68. 3. Trundle (2004), 8–9. 4. Ibid., 4–5. 5. North (1981), 3; Scheidel, Morris, and Saller (2008), esp. 1–12; Bang (2009). 6. Bang (2009), 204; cf. Rowan (2013), 366–9. 7. Matthew’s ideas in this sphere were aligned broadly with Mauss’s (2016) ‘gift’, although he never explicitly used this model himself. 8. Kallet-Marx (1993), esp. 21–36. 9. Ibid., 35–6. 10. Trundle (2011). 11. Ibid., 240. 12. Cf. Osborne and Rhodes (2017), 151. 13. Parker (1983), 170–4. 14. Hornblower (1996), 364–5. 15. Kroll (2011), 251–4. 16. Samons (2000); Blamire (2001). 17. Trundle (2016), 67. 18. Stanley (1986); Schaps (2004), 74–7; Tandy (1997), 72–5; cf. Il. 9.71–2. 19. Hornblower (1991), 36 for the incoherence. 20. Cf. Pritchett (1971), 30–1. 21. Woytek (2012), 329. 22. Frank (1933), 83–4. 23. Kallet (2001), 21–66. 24. Schaps (2004), 209–10. 25. Kallet and Kroll (2020), 126.

7

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World 26. Rowan (2019), 2–4 and 34. 27. Howgego (1995), 51. 28. Weinstock (1957), 219–20.

Bibliography Bang, P. (2009), ‘The Ancient Economy and New Institutional Economics’, JRS 99: 194–206. Blamire, A. (2001), ‘Athenian Finance 454–404 b.c.’, Hesperia 70: 99–126. Frank, T. (1933), An Economic Survey of the Roman Republic, vol. 1, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. Hornblower, S. (1991), A Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 1, Books I–III, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Hornblower, S. (1996), A Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 2, Books IV–V.24, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Howgego, C. (1995), Ancient History from Coins, London: Routledge. Kallet, L. (2001), Money and the Corrosion of Power in Thucydides: The Sicilian Expedition and Its Aftermath, Berkeley: University of California Press. Kallet, L. and J. Kroll (2020), The Athenian Empire: Using Coins as Sources, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kallet-Marx, L. (1993), Money, Expense, and Naval Power in Thucydides’ History 1–5.24, Berkeley: University of California Press. Kroll, J. (2011), ‘The Reminting of Athenian Coinage, 353 b.c.’, Hesperia 80.2: 229–59. Kroll, J. (2012), ‘The Monetary Background of Early Coinage’, in W. Metcalf (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Coinage, 33–42, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mauss, M. (2016), The Gift, trans. J. Guyer, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Originally published as: Mauss, M. (1923–4), ‘Essai sur le don: Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques’, L’Année sociologique n.s. 1: 30–186. North, D. (1981), Structure and Change in Economic History, New York: Norton. Osborne, R. and P. J. Rhodes (2017), Greek Historical Inscriptions: 478–404 b.c., Oxford: Oxford University Press. Parker, R. (1983), Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pritchett, W. K. (1971), The Greek State at War, Part 1, Berkeley : University of California Press. Rowan, C. (2013), ‘The Profits of War and Cultural Capital: Silver and Society in Republican Rome’, Historia 62 (3): 361–86. Rowan, C. (2019), From Caesar to Augustus (c. 49 bc to ad 14): Using Coins as Sources, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Samons, L. II. (2000), The Empire of the Owl: Athenian Imperial Finance, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner. Schaps, D. (2004), The Invention of Coinage and the Monetization of Greece, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Scheidel, W., I. Morris and R. Saller, eds (2008), The Cambridge Economic History of the GrecoRoman World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stanley, P. (1986), ‘The Function of Trade in Homeric Society’, Münstersche Beiträge zur Antiken Handelsgeschichte 5.2: 5–15. Tandy, D. (1997), Warriors into Traders: The Power of the Market in Early Greece, Berkeley : University of California Press. Trundle, M. (2004), Greek Mercenaries from the Late Archaic Age to Alexander, New York: Routledge.

8

Money, Power and Legacy Trundle, M. (2011), ‘Coinage and the Transformation of Greek Warfare’, in G. Fagan and M. Trundle (eds), New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, 227–52, Leiden: Brill. Trundle, M. (2016), ‘Coinage and the Economics of the Athenian Empire’, in J. Armstrong (ed.), Circum Mare: Themes in Ancient Warfare, 65–79, Leiden: Brill. Weinstock, S. (1957), ‘Victor and Invictus’, HTR 50 (3): 211–47. Woytek, B. (2012), ‘The Denarius Coinage of the Roman Republic’, in W. Metcalf (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Coinage, 315–34, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

9

10

CHAPTER 2 THE UPKEEP OF EMPIRE: COSTS AND RATIONS Anthony Spalinger

When considering warfare, one must keep in mind not only military objectives but also the means through which they may be obtained. Armies, for example, need to be fed, which involves not just food but also transport for that food, involving in turn calculations about numbers of men, numbers of days, terrain – friendly or not – to be covered, and the means of transport. With that in mind, this chapter attempts a cost analysis of one New Kingdom Egyptian campaign: Thutmose III’s famous defeat of a coalition of Palestinian and Syrian ‘rebels’ at the logistically significant city of Megiddo c. 1457 bce .1 The larger purpose of this analysis is to see Thutmose’s campaign in terms of the relation, particularly the monetary relation, between the Egyptian war machine and the maintenance of the extended pharaonic state. The Megiddo campaign, and its successful conclusion, is historically significant for the extent of contemporary official records kept and promulgated by Thutmose’s order. In particular, the Annals of Thutmose, found in a series of inscriptions at the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, which record this campaign and others. Pertinent inscriptions also appear elsewhere. Yet they are not enough to develop a straightforward equation involving numbers of men, loaves of bread, and so forth. For that, we must tease out a more complete picture by piecing together relevant information from other sources found both earlier and later in time, written or otherwise, dealing with military campaigns as well as commercial enterprises that involved large numbers of people and supplies on the move in the ancient Egyptian world. In what follows, the focus is on grain supplies, for which our data is relatively solid. Ultimately, we can but make assumptions, sometimes based on assumptions made by others before us, about not just grain supplies but also the size of armies and their standard practices affecting the cost of their operations. How many soldiers were involved in this particular campaign, and how long did Thutmose’s army take to travel from the Western Delta to Tjaru in the Eastern Delta, cross the Sinai desert, march through the Aruna Pass and finally reach Megiddo? How many Egyptians back home did it take to grow the grain the men set out with and found in some of the granaries under Egyptian control along the way, especially between eastern Egypt and Gaza? How did the existence of those granaries affect the army’s need to transport grain, and how did the advance through physically diverse territory governed by previously subdued small city-states also play a part in our hypothetical quartermaster’s calculations? Previous research, including my own, has attempted to determine the size of Thutmose’s army at Megiddo and that of the Megiddo coalition that he faced.2 The 11

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

population of Egypt itself, as calculated by Manning (albeit for a much later, Ptolemaic Egypt), was c. 500,000 adults.3 This result is suggestive of a 7,500 or even a 10,000 strong army force. While Redford estimated 10,000 men on the Egyptian side,4 my original estimate was c. 5,000 men.5 Manassa’s work on a Ramesside-era literary account of Thutmose’s siege of Megiddo suggests that the Egyptians employed 1,900 chariots.6 Since this figure lends credence to my earlier estimate of 2,000 chariots, I now maintain that the Egyptian army totalled c. 7,500 men, for, along with his battle-trained troops, Thutmose’s army would have included various non-combatant assistants, such as the cadets and the men and boys whom Heagren calls ‘porters’.7 The Egyptians captured 924 chariots from the enemy,8 so we can assume that the ratio between Egyptian and enemy war vehicles was around 2/1. We can assume that Thutmose took twelve days to go from Gaza to Yehem, a town situated near the first of Thutmose’s options for taking his army inland toward Megiddo, and then two more days to arrive at the Aruna Pass, his second option. Some additional days would be involved in taking apart the chariots, marching through the pass and reconstructing the chariots before the battle could commence.9 It is useful to keep in mind that Redford has calculated a ten-day limit for carrying soldiers’ rations across the Sinai,10 and Heagren has calculated what we might expect for the army’s speed.11 Nonetheless, some inexactitude remains and 27–28 days is what we can assume. Although Oren contends that in the period before Thutmose III’s march to Megiddo the Sinai route witnessed no ‘organized military expeditions between the reign of Ahmose and the joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III’,12 well-traversed roads were Thutmose’s arteries of advance, as they were the sure means of getting to localities where food supplies could be found in fortified granaries, within the walls of previously subdued cities, or in fields available for Thutmose’s use. The network of the Ways of Horus depended upon the redistributive patterns for goods, such as grains, established by the Egyptians before regnal year twenty-two of Thutmose III. Such a network suggests a degree of administrative sophistication that Schulman’s admittedly dated study has described. The soldiers no longer had to obtain basic supplies, such as food and equipment, for themselves.13 The government provided rations and materiel, set a clear organizational structure, required some degree of training and brought in officers from well-established families of the administrative class. Oren concurs with Schulman about the degree of Egyptian administrative control, noting that Egyptian control over the Sinai route and Gaza existed before Thutmose III’s independent reign.14 By the time Thutmose’s army set out for Megiddo, ‘Foodstuffs and other provisions required by the armies on the journey across the Sinai desert were stored in forts and administrative centers along the WOH’.15 Redford also has argued that the troops and supporting animals would have had enough supplies to cover the trip to Gaza.16 After only one day in Gaza, after reaching that city from the Sinai, Thutmose III’s army was equipped to travel north, because it had sufficient supplies. Kemp’s analysis of the Middle Kingdom fortresses as sites of protected granaries revealed that, while they had to ‘maintain secure supplies of grain for the campaigning armies’, the extent of those supplies varied with fluctuations in the Egyptian army’s size 12

The Upkeep of Empire: Costs and Rations

and activities.17 The fort at Askut, for example, probably served as a ‘fortified grain store’ and thus could handle any increase in soldier numbers.18 Nonetheless, it remains sub judice whether an army in excess of 5,000 men could have been provided for by these depots. On the other hand, it was necessary for the Egyptian state to ‘support an empire with the minimum of operating costs’.19 For our purposes we may ignore the costs of garrisons, etc. To me the issue is one of metrics – namely how large were the storehouses in all of the Sinai garrisons, and how much could they provide in grain for an extensively prepared campaign northwards? Before leaving pharaonic Egyptian administrative practices entirely behind, let us acknowledge that budgeting was an active practice, as evidenced by the papyrus known as P. Anastasi I. There, among other things, we find examples of the practical skills Egyptian officers were expected to have, including how to calculate daily rations of bread for a unit of 5,000 soldiers.20 Schulman concluded that a New Kingdom army company consisted of 250 men and hence an army of 5,000 men divided into twenty companies.21 Mueller’s research on wage rates, which discussed an expedition to the Wadi Hammamat and the use there of P. Rhind (exercise 65) as an exemplar of mathematical calculations at the time, leads him to observe that: ‘Egyptian bookkeepers employed the device of converting rations into a fictitious number of people to calculate their expenditure’.22 Unfortunately, such an artificial mathematical exercise cannot, for example, be used to determine the exact caloric intake of workers, be they soldiers or not.23 But all is not lost, as we shall see below. Once Thutmose’s army was on the road, its system for transporting supplies involved porters (based on Ramesside examples visible in the Kadesh reliefs), but it also required animals, both pack and draught. Horses, primarily associated with chariots, are the only animals mentioned by the Annals as being present in the Aruna Pass.24 However, both oxen and donkeys were used as pack and draught animals by Hittites, Egyptians and others from the Early Bronze Age. Yet neither the Megiddo nor the Kadesh accounts indicate the presence of oxen, perhaps because, as Heagren’s mathematical data show, oxen would slow the army down. By the Late Bronze Age, though, as Heagren argues, donkeys were primary components of military transport systems. Since his work on the subject, Shai et al. have covered in detail the usefulness, cost and upkeep of these animals,25 and Bar-Oz et al. have studied an important burial site for a donkey at Tell Haror that indicates ‘the centrality of the donkey as a pack animal in societies for which caravans played a pivotal economic role’.26 While I do not believe that oxen played any important role in Thutmose’s Megiddo campaign, I am convinced that Thutmose III used donkeys as pack animals,27 as supported by the following points. Archaeological data from the Early Bronze Age in Canaan reveals that donkeys carried heavy goods over rough terrain. Granted that this discussion was limited mainly to Early Bronze Age III society, it nevertheless revealed that donkeys were excellent beasts of burden both during warfare as well as for long-distance commercial transport. A donkey’s value for transport rested not least on its ability to carry about 75-kilogram loads; donkeys could cover c. 24 kilometres/day, given six hours of marching and occasional rest days at 13

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

regular intervals. Oxen, on the contrary, clock in at either 15 kilometres/day or 19–24 kilometres/day. Cheaper to maintain than an ox, as well as faster, donkeys are also far less demanding than horses in terms of food intake and have superior endurance. Fodder was needed as well as water for the pack and draught animals,28 and the use of hard or dry fodder appears in Ramesses II’s Kadesh reliefs.29 Records of provisions for the animals show a tripartite division of animal feed into hard fodder (e.g. barley and oats), green or dry fodder (crops grown on farms especially for animals such as hay, straw, clover and broad beans), and pasturage.30 As Heagren observes, fodder is difficult to transport over long distances and likely to be the first source to run out should logistical difficulties arise.31 Considering equal size, donkeys not only eat less, but also lower quality (and hence less costly) food than either horses or oxen. The suggested dietary intake for oxen is c. 7 kilograms of hard fodder and 11 kilograms of dry and green fodder.32 Dietary requirements for donkeys, according to Heagren, are 1.5 kilograms of hard fodder and 5 kilograms of green fodder per day.33 The necessity of providing provisions for the animals across the Sinai is thus apparent, but it is selfevident that, once the Egyptians reached Gaza and the Asiatic cities beyond, the enemies’ agricultural domains could be efficiently sequestered for the animals’ upkeep, at which point pasturage would have been the easiest food to obtain. It is worth noting that foraging off the land applies at this point to the soldiers themselves. The distinction between green and dry fodder is not simple to define. As Heagren observes, ‘less dry fodder was needed than green fodder in order to provision a horse’,34 and he estimates that horse rations were around 2.5 kilograms of hard fodder and 7 kilograms of green/dry fodder each day.35 As for water, horses consume a lot – 15 litres/day at the minimum to 30 plus. Even grazing was insufficient for this purpose, since horses, which consume c. 14 kilograms of forage daily, still need some dry (hard) fodder, or else they soon get ill, especially when working arduously.36 Hence it was necessary to provide hard or dry fodder as well as letting them graze, or to use the local supply centres and vassal cities. Moving on to the cost of ‘fuelling’ Thutmose’s human army, we must limit ourselves largely to one component of the food available to his soldiers: grain.37 Warburton estimated, very roughly, the Ramesside income in grains to be 30 million litres per year, but he qualifies his figures and provides others that appear to contradict his estimate.38 Manning, concentrating upon Ptolemaic Egypt, sets the actual grain revenue at 6 million artabas of wheat, enough to feed 500,000 adults.39 Although data on military rations40 rarely appear in ancient Egyptian accounts, much of our data for grain supplies is solid. However, when we do find the number of breads or beers involved, the ‘cooking ratio’ – or loss from processing grain into consumable food and drink – is unknown, making it impossible to determine the original amount of grain (and the approximate weight of the item), or the resultant caloric intake.41 Looking at the problem from the other end of the telescope, temporary swellings of the Egyptian army during military campaigns complicate budgeting for minimum and maximum annual ration units, in the same way that soldiers resident in garrisons would complicate budgeting because they would most likely require fewer calories than soldiers actively engaged in warfare.42 14

The Upkeep of Empire: Costs and Rations

However, let us begin to pick apart our problem by considering what we know about ‘rations’, and attempt to establish the relation between a ration’s weight and its calories, as well as the number of rations/calories a soldier received per day. Kaplony-Heckel’s study of demotic ostraca from Armant introduces us to ‘q, apparently the term for a standard ration of bread.43 Kemp’s study of XIIth Dynasty Middle Kingdom granaries within fortresses in Nubia discusses rations and granary capacity, leading to some conclusions with regard to maximum and minimum ‘annual ration units’ based on one kg grain/day/ soldier as a reasonable upper limit to expect. Even better for our purposes, Deir el Medineh provides us with useful details about a New Kingdom settlement of unskilled labourers working on the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, despite its belonging to a slightly later era. At its high point, the village housed c. 120 workmen and their families. Estimates of the total population vary from a minimum of 500 to as many as 1,200 people during Dynasties XIX (c. 1292–1190 bce ) and XX (c. 1190–1075 bce ).44 The basic grain rations per month at Deir el Medineh were 4 sacks of emmer wheat and 1.5 sacks of barley. Janssen concluded that this grain ‘was amply sufficient for a family of about ten persons, including some small children’.45 There were also lower rations for young men: 1.5 sacks of wheat and 0.5 sack of barley. Considering the amount of grain in these rations surplus to requirements, Janssen asserts that the workmen ‘used part of their rations to barter in exchange for other commodities’,46 such as figs, vegetables and water; beer (as with additional processed cakes) probably came from the redistribution of foods offered to the gods.47 Thus we find a sort of benchmark for comparing rations for an active soldier with a Deir el Medineh workman’s total monthly ration. First, though, we must try to determine an active soldier’s daily ration, as well as the relation between rations and calories. Kemp’s research led him to believe that the daily ration of grain was c. 1 kilogram, equal to 1,458 calories/day.48 Reliant in part on previous scholarly research, he cautiously estimated the minimum caloric intake per soldier per day to be 3,500 calories.49 Heagren significantly refined this analysis in his survey of arguments put forward by previous scholars for a range of from 3,000 to 3,600 calories per day.50 Roth, for example, was correct in pointing out that a calorie intake of 3,600 for the soldiers of the Macedonian army, as estimated by Engels, was too high.51 Engels based this figure on the recommended amount of required calories as stated by the US Army for a soldier on active service.52 Roth argued that an average Roman legionnaire, being of lesser stature (and older), required fewer calories and less protein. The same could be said for a Macedonian and of course an Egyptian. Winlock’s study showed that the average height of the sixty or so slain Egyptian soldiers in the mass grave he was excavating was 169 centimetres, and that their average age was between thirty and forty years.53 If these individuals were in reasonable shape, then their ideal weight would have been around 65 kilograms.54 Heagren further notes that, ‘According to the U.S. Army figures, an average 30–40 year old individual needed only 3000–3200 calories per day whereas a 16–19 year old needed 3600 calories.’55 Roth, an expert on the Roman army, indicated that the figure of 15

Money, Warfare and Power in the Ancient World

3,000 calories was the recommended amount and not a minimum requirement.56 A soldier of modern times could (and often does) operate on less than this, although any great decrease could debilitate a soldier both physically and mentally within a few days.57 Let us consider the relation between calories and rations from a different angle. P. Anastasi I seems to suggest a distribution of food for 5,000 men, which Heagren has diagrammed as shown in Table 2.1. That gives us a relation between number of men and number of loaves of bread from a roughly contemporary source. However, Heagren regarded the number of loaves and cakes to be small for 5,000 military men per day.58 As an interesting aside that sheds light on how a day on the march might play out, the foods, called a ‘peace gift’, appear to be handed out in the morning. The army is to have set off at midday and expected to reach the final destination before nightfall. Before setting off, though, let us consider ancient Egyptian units of measurement, particularly the heqat (barrel), the khar (sack), and the deben (weight), which varied over time. From Janssen, we will accept the following as appropriate for Thutmose’s era: 1 khar = 2 deben of copper, and 76.88 litres = 2 deben of copper.59 Kemp’s study of Middle Kingdom fortresses provides the following data: 1 heqat of emmer wheat = 3.75 kilograms; somewhat lighter than wheat, 1 heqat of barley = 2.25 kg; 1 kilogram wheat = 0.27 heqat; and 1 kilogram barley = 0.44 heqat. If 1 sack = 16 heqat = 2 copper deben, then 1 heqat = 1/8 deben; 0.27 heqat of wheat comes out to be 0.034 deben and 0.44 heqat of barley is 0.055 deben. The last two results refer to a daily output of processed grain rations for one soldier.60 In an Egyptian record from the regnal year six of Seti I that was found at the Gebel Silsileh quarries, we can learn about rations for 1,000 soldiers who were dispatched to bring back sandstone.61 The weight of the bread, given as 20 deben, would have sufficed for most of the men’s food intake. Following Roman source material, Heagren estimated that the caloric values of the supplies were as shown in Table 2.2.62 Since the pharaoh states that he had increased the provisions for his army, the breads – at 20 deben/person – come to c. 4,175 calories. While the bread formed 73.3 per cent of the daily rations, fresh vegetables came to 4.2 per cent and meat 22.5 per cent. The men also received two sacks of grain per a month of thirty days, which may have been associated with wages, but this is a different aspect of how rations may have functioned.63 We can now reasonably assume that, on its march to and battle for Megiddo, Thutmose’s army would have to carry with it at least the equivalent of c. 3,000 calories/man/day. However, as Heagren observes, to meet daily requirements for protein as well as calories,

Table 2.1 Provisioning of soldiers, based on P. Anastasi I

16

Provisions

Quantity

Bread

300 loaves

Cakes

1,800

Goats

120

Wine

30 measures

The Upkeep of Empire: Costs and Rations

Table 2.2 Daily calorific value of provisions as estimated by Heagren (2012, 169–72) Item

Quantity

Weight

Calories

Protein

Bread

10 deben

0.91 kg

2,087.5

80.5 g

Vegetables

1 bundle

50 g

170

10 g

Roast beef

1 portion

160 g

640

15 g

1.12 kg

2897.5

105.5 g

Totals: