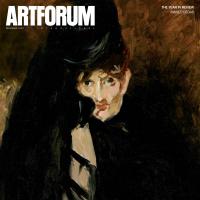

Looking Critically: 21 Years of Artforum Magazine 0835715361

1,100 42 32MB

English Pages [358] Year 1984

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

M0

/ V / >

L *7

/ £>

Cover Design: Roger Gorman Design Coordination: Mary Beath

Copyright © 1984 Artforum All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an Imprint of University Microfilms International Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

LC 83-24345 ISBN 0-8357-1536-1 hardcover ISBN 0-8357-1549-3 softcover

Preface

ARTICLES

ix

FANTASTIC ARCHITECTURE, by Kate Trauman Steinitz (1/3 August 1962).2 SAM FRANCIS: FOUR DRAWINGS [MALICE IN BLUE (fragments for Sam), by Yoshiaki Tono] (116 November 1962).6 NOTES ON THE NATURE OF JOSEPH CORNELL, by John Coplans (i/a February 1963).8 KANDINSKY, by Hilton Kramer (tm May 1963). 10 ANTI-SENSIBILITY PAINTING, by Ivan C. Karp (il/3 October 1963). 14 OPEN LETTER TO AN ART CRITIC, by Clyfford Still (1116 December 1963). 16 ON CRITICISM, by Harold Rosenberg (ilia February 1964). 18 AN INTERVIEW WITH GEORGE SEGAL, by Henry Geldzahler (11112 November 1964)..20 JOHN CAGE IN LOS ANGELES, by John Cage (11115 February 1965).22 AN INTERVIEW WITH JASPER JOHNS, by Walter Hopps (IIII6 March 1965).25 DISCUSSION, by Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenberg, Andy Warhol (ivie February 1966).29 THE HAPPENINGS ARE DEAD. . .LONG LIVE THE HAPPENINGS!, by Allan Kaprow ((IV/7 March 1966) . . .33 SURREALISM [cover], by Ed Ruscha (vn September 1966).37 THIS IS NOT RENE MAGRITTE, by Roger Shattuck (Vli September 1966).38 PICASSO AS SURREALIST, by Robert Rosenblum (vn September 1966).41 SOME REMARKS, by Dan Flavin (V/4 December 1966).45 TALKING WITH TONY SMITH, by Samuel Wagstaff, Jr. (v/4 December 1966).48 THEATER AND ENGINEERING: AN EXPERIMENT, by Billy Kluver (VI6 February 1967). 53 SOL LEWITT: NON-VISUAL STRUCTURES, by Lucy Lippard (Via April 1967).56 ART AND OBJECTHOOD, by Michael Fried (VlioJune 1967).61 PROBLEMS OF CRITICISM, I, by Robert Goldwater (vin September 1967).69 CHRONOLOGY, by Ad Reinhardt (Vin September 1967). 71 THE SERIAL ATTITUDE, by Mel Bochner (Vi/4 December 1967). 73 PROBLEMS OF CRITICISM IV: POLITICS OF ART, PART 1, by Barbara Rose (vile February 1968).78 FILMS OF JEAN-LUC GODARD, by Manny Farber (vil/2 October 1968).80 A VARIETY OF REALISMS, by Sidney Tillim (VimoJune 1969).83 SOME NOTES ON THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF MAKING: THE SEARCH FOR THE MOTIVATED, by Robert Morris (Vlll/8 April 1970).88 AN INTERVIEW WITH EVA HESSE, by Cindy Nemser (vmi9 May 1970).93 HOW I SPENT MY SUMMER VACATION OR ART AND POLITICS IN NEVADA, BERKELEY, SAN FRANCISCO AND UTAH, by Philip Leider (ix/1 September 1970).98 HANS HAACKE'S CANCELLED SHOW AT THE GUGGENHEIM, by Jack Burnham (ix/iOJune 1971).105 "PAUL REVERE,” by Joan Jonas and Richard Serra (X/i September 1971).110 MEDITATIONS AROUND PAUL STRAND, by Hollis Frampton (X/6 February 1972).1 12 MARK Dl SUVERO, by Carter Ratcliff (Xil3 November 1972).116 A NOTE ON BERNHARD AND HILLA BECHER, by Carl Andre [and Marianne Scharn] (XI14 December 1972).122 A PORTFOLIO, by Lucinda Childs (Xii6 February 1973).124 FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED AND THE DIALECTICAL LANDSCAPE, by Robert Smithson (XI16 February 1973).130 AGNES MARTIN, by Lawrence Alloway (xi/8 April 1973).137 REFLECTIONS, Agnes Martin (Xi/8 April 1973).141 FUNCTION OF THE MUSEUM, by Daniel Buren (xim September 1973).142 "ANEMIC CINEMA” REFLECTIONS ON AN EMBLEMATIC WORK [Marcel Duchamp], by Annette Michelson (XI112 October 1973).143 SENSE AND SENSIBILITY-REFLECTION ON POST '60S SCULPTURE, by Rosalind Krauss (XIII3 November 1973).149 A HUMANIST GEOMETRY [Robert Mangold], by Joseph Masheck (Xii/7 March 1974).157

THE ART COMICS OF AD REINHARDT, by Tom Hess (xn/8 April 1974).

160

TALKING WITH WILLIAM RUBIN; “THE MUSEUM CONCEPT IS NOT INFINITELY EXPANDABLE,” interview by John Coplans and Lawrence Alloway (xmi2 October 1974).

.166

THE ART MARKET: AFFLUENCE AND DEGRADATION, by Ian Burn (XIIII8 April 1975).

,173

PAINTING AND ANTI-PAINTING: A FAMILY QUARREL, by Max Kozloff (Xivn September 1975).... ALTMAN IN MUSIC CITY, by Stephen Farber (xiv/3 November 1975).

.177 .183

INSIDE THE WHITE CUBE [1 ]: NOTES ON THE GALLERY SPACE, by Brian O'Doherty (xiv/6 March 1976).

.188

RHODA IN POTATOLAND [Richard Foreman], by Steven Simmons (xivie March 1976)

.194

MARCEL BROODTHAERS’ THROW OF THE DICE, by Nicholas Calas (Xivi9 May 1976). MINIMALISM AND CRITICAL RESPONSE, by Phyllis Tuchman '(xv/9 May 1977).

.196

.200

ALFRED JENSEN: SYSTEMS MYSTAGOGUE, by Donald B, Kuspit (XVi/8 April 1978).

.204

ART IN RELATION TO ARCHITECTURE, ARCHITECTURE IN RELATION TO ART, by Dan Graham (XVII/6 February 1979). ARTRACE™, AN HERETICAL BORED GAME, by Heresies Collective (XVM/6 February 1980). THE BARREN FLOWERS OF EVIL, by Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid (xviii/7March 1980) THE LIGHTNING FIELD, by Walter DeMaria (Xvin/8 April 1980). A CHAMELEON IN A STATE OF GRACE [Francesco Clemente], by Edit deAk (Xix/6 February 1981) THE END OF THE AVANT-GARDE? AND SO, THE END OF TRADITION., by Bazon Brock (X/X/10 June 1981).

PROJECT, by Anselm Kiefer (xixno June 1981). VIOLENCE OF ARCHITECTURE, by Bernard Tschumi (xxn September 1981).

.208 .215 .219 .224 .226 .230 .235 .238

PORTRAITS. . . NECROPHILIA, MON AMOUR, by Joseph Kosuth, SECTION 2 by Lawrence Weiner, IMPASSIONED WITH SOME SONG WE, by Kathy Acker, PORTRAITS, by Robert Mapplethorpe (XXI9 May 1982). GRIM FAIRY TALES, by Kate Linker (xxm September 1982).

.242 .254

HEADS IT'S FORM, TAILS IT'S NOT CONTENT, by Thomas McEvilley \xxil3 November 1982). CHILD ABUSE, by Louise Bourgeois (xxii4 December 1982). EDITORIAL, by Ingrid Sischy, Germano Celant (xxi/9 May 1983). AT THIS QUICK AND WEIGHTLESS MOMENT, by Lisa Liebmann (xxi/9 May 1983).

.256 .264 .272 .273

IE1ATS Volume 1

EDWARD KIENHOLZ, by Arthur Secunda (June 1962).

JOSEF ALBERS, by Henry T. Hopkins . .274

BRUCE CONNER, by Constance Perkins

(November 1962)

FRANK STELLA, by Donald Factor (May 1963)... . .274 JOHN CHAMBERLAIN, by John Coplans

(August 1962).

LOUISE NEVELSON, by Arthur Secunda

(March 1963) . . .

(August 1962).

ANDY WARHOL, by Henry T. Hopkins (September 1962) ....

Volume II

AD REINHARDT, by Donald Factor (January 1964) ..275 DON JUDD, by Lucy Lippard (March 1964) . .275 ROBERT MANGOLD, by Lucy Lippard

WERNER BISCHOF, by Margery Mann (September 1963) . . .

(March 1964).

Volume III

MILTON AVERY, by Fidel A. Danieli (November 1964). ELLSWORTH KELLY, by Irving B. Petlin (May 1965).

Volume IV

ELIOT PORTER, by Margery Mann (June 1965) .. . .276 JAMES ROSENQUIST, by William Wilson (December 1964)

ELLSWORTH KELLY, by Fidel A. Danieli (May 1966).

JASPER JOHNS, by Robert Pincus-Witten (March 1966)

CLAES OLDENBURG, by Dennis Adrian (May 1966).

LARRY BELL, by Donald Factor (January 1966). H.C. WESTERMANN, by Dennis Adrian (January 1966) ....

AGNES MARTIN, by Susan R. Snyder MARK Dl SUVERO, by Nancy Marmer (December 1965).

Volume V

HANS HOFFMANN, by Rosalind Krauss (April 1966). .278

ROBERT IRWIN, by Max Kozloff (January 1967)

. . .

. .

.276

ROBERT SMITHSON, by Robert Pincus-Witten .281

RED GROOMS, by Dennis Adrian (March 1967)... .281

. .279

SAUL STEINBERG, by Whitney Halstead (April 1967).

Volume VI

282

INGMAR BERGMAN, “Hour of the Wolf,” by Manny Farber (May 1968).282 MARTIAL RAYSSE, by Jane Livingston (September 1967).282

“The Sweet Flypaper of Life," text by LANGSTON HUGHES, photographs by ROY DE CARAVA,

RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER, by Robert Pincus-Witten (March 1968).283 ALICE NEEL, by Jane Harrison Cone (March 1968) .283

by Margery Mann (April 1968).286 CARL ANDRE, by Philip Leider (February 1968) ... .286

WALTER DE MARIA, MARK Dl SUVERO,

TONY SMITH, by Emily Wasserman (April 1968) . . .286 RICHARD TUTTLE, by Emily Wasserman

RICHARD SERRA, by Robert Pincus-Witten (April 1968).284

Volume VII

Museum of Modern Art, the Fort Knox of film footage, by Manny Farber (April 1968).284 JIM DINE, by Emily Wasserman (October 1967) ... .285

(March 1968).287

WHITNEY ANNUAL, by Max Kozloff

LUCAS SAMARAS, by Robert Pincus-Witten “HAIRY WHO,” by Whitney Halstead

(February 1969).290 FRANCIS BACON, by Robert Pincus-Witten

(October 1968).288 JACK BEAL, by Robert Pincus-Witten

(January 1969).291 MICHAEL SNOW, by Manny Farber

December 1968)..288 RALPH HUMPHREY, by Robert Pincus-Witten (April 1969).289

(January 1969).292 ROBERT MOTHERWELL, by Emily

ANTHONY CARO, by Rosalind Krauss

JOSEPH KOSUTH, JOHN BALDESSARI

(December 1968).287

(January 1969).289

Wasserman (December 1968).293 by Jane Livingston (December 1968).293

ALAN SHIELDS, by Emily Wasserman (December 1968).289

Volume VIII

ART IN PROCESS, IV, by Philip Leider (February 1970).294 RICHARD SERRA, by Philip Leider (February 1970).294 HELEN FRANKENTHALER, by Jean-Louis

Bourgeois (January 1970).295 VIJA CELMINS, by Peter Plagens (March 1970) .. . .295 RICHARD DIEBENKORN, by Terry Fenton

Volume IX

JAMES BYARS, by Thomas H. Garver (January 1970).296 EDWARD RUSCHA, by Emily Wasserman (March 1970).297

PAINTING IN NEW YORK, 1944-69 and WEST COAST, 1945-69, by Peter Plagens

(January 1970).296

(February 1970).297

NANCY GRAVES, by Kasha Linville (March 1971), .298

DOROTHEA ROCKBURNE, by Robert Pincus-Witten (February 1971).300

ROBERT SMITHSON, by Joseph Masheck (January 1971).298 KEITH SONNIER, by Peter Plagens ('October 1970). .299

R.B. KITAJ, by Jerome Tarshis (Summer 1971).299

Volume X

WILLIAM WILEY, by Peter Plagens (February 1970).296

JOHN De ANDREA, by Lizzie Borden (January 1972).301

MEL BOCHNER, by Lizzie Borden (April 1972) ... .301 CY TWOMBLY, by Ken Baker (April 1972).302 KENNETH SNELSON, by Ken Baker (April 1972) .. .302

LANGUAGE, by Robert Pincus-Witten (September 1970).300 KEN PRICE, by Kasha Linville (March 1971).300

GROUP DRAWING SHOW, by Robert Pincus-Witten (February 1972).303 MASTERS OF EARLY CONSTRUCTIVIST ABSTRACT ART, by Joseph Masheck (December 1971).304

GILBERT & GEORGE by Robert Pincus-Witten (December 1971).302

Volume XI

JOSEPH BEUYS, by Lizzie Borden (April 1973) . . . .304

LAURA DEAN, by Lizzie Borden

SYLVIA MANGOLD, by April Kingsley

(February 1973).306 LYNDA BENGLIS, by Bruce Boice (May 1973).307

(December 1972).305

HARRY CALLAHAN, by Lizzie Borden

WILLIAM WEGMAN, by Bruce Boice (January 1973).305

(February 1973).307

JANNIS KOUNELLIS, by April Kingsley (January 1973).306

Volume XII

LUCIO FONTANA, by Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe

JACKIE FERRARA, by Laurie Anderson (January 1974).308

ARTISTS’ BOOKS, by James Collins (December 1973).308 BRICE MARDEN, by Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe VII

(May 1974).

309

(May 1974).309 PHIIP PEARLSTEIN, DUANE HANSEN, by Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe (April 1974).310 MARIO MERZ, by Roberta Smith (February 1974) .. .310

< •

-

'

ARTICLES

Fantastic Architecture

Kate Trauman Steinitz There have been at all times and in all countries builders who saved their souls from drowning in the ocean of conformity by living a life of their own on the Island of Fantasy. Most of them were lone men, some highly trained professional architects, some selftaught craftsmen only. The ideas of the professionals who knew how to draw frequently remained utopic plans on papers; but the untrained men, such as Post¬ man Cheval and Sam Rodia had no means of premedi¬ tating on paper. They had no other way of expressing themselves than to set forth with their own hands what their imaginations dictated to them. “It is all in my head” answered Sam Rodia, when asked for his blue¬ prints. SIMON RODIA'S TOWERS OF WATTS, CALIFORNIA On the southeastern outskirts of the City of Los An¬ geles, diametrically opposed in any respect to the glamour of the city of Hollywood, in a drab neighbor¬ hood without glamor, one would expect anything else but a colorful garden with three giant towers. Soaring to the height of 96 feet in the midst of Mexican and colored folks who struggle hard for the necessities of life, Sam Rodia’s towers stand as a purposeless tribute to beauty. They are a phenomenon both of construc¬ tion and of human energy. The Italian craftsman Simon, or Sam, Rodia, a tile setter, built this greatest structure ever made by one man, single handed, using simple tools without the use of machines. He im¬ pressed his tools into the concrete of his construc¬ tion. He could not afford a helper, he said, moreover he would not have been able to tell him what to do. Once Sam had conceived the idea of “doing some¬ thing big” he remained obsessed by it for 30 years. James Johnson Sweeney called Sam a born construc¬ tion genius. Sam bent his iron rods in the most prim¬ itive way, without measuring instruments, under a

railroad track. His innate feeling for equilibrium made the Towers rise straight and firm. However, the of¬ ficials of the Los Angeles Building and Safety De¬ partment stated “the Towers are built of scrap, Seven-up bottles and sea shells.” They ignored the sound construction and the fact that the colorful mosaic was also protection for the reinforced con¬ crete. A 10,000 pound load test had to be applied to the highest Tower. It stood firm and proud during this rigorous test and thus escaped demolition. Sam was an inventive artist. Each tower has its own form and rhythm. One has rings bulking in measured proportion, while the inner forms are straight and angular. Another tower rises straight, but through the open transparent structure one can see the round forms of the inner structure. There are buttresses, pavilions, labyrinths and fountains and a passage-way roofed with broken mirrors. Seven-Up bottles make good finials; broken, they make patterns of odd forms with highlights on their curvatures; pulverized they cover stalagmites near the fountain like wet moss in a virgin forest. Jules Langsner, who was one of the first to write about the Towers, told me a human in¬ terest story: One Sunday he met Sam, washed and scrubbed clean, wearing a sleeveless shirt. The brown arms shimmered with splinters of pulverized glass which had settled deep in his leather-hard skin. Sam had become a part of his mosaic. In spite of his devotion to the Towers Sam Rodia abandoned them at the age of 75, feeling his strength declining. The Towers were neglected, his house burnt down by vandals. After the Building and Safety authorities condemned the Towers, two courageous artists, William Cartwright and Nicholas King, ac¬ quired them in order to save them. They were assisted by other artists and intellectuals who formed the “Committee for Sam Rodia’s Towers in Watts.” The Towers now belong to the Committee.

Watts Towers. William Cartwright, photographer. It has taken over the responsibility of maintaining them and making the grounds a cultural center for the community. The circle of friends, even abroad, is growing with the fame of the towers. Sam Rodia, now living as a recluse in Northern California, and who had refused to take any interest in the Towers, is starting to enjoy the recognition of the “big thing” he ac¬ complished. THE PALATIAL GROTTO of POSTMAN FERDINAND CHEVAL in HAUTERIVES (Drome) France, built 18781912. A mail carrier used to pace patiently thirty kilo¬ meters a day through the countryside. He liked to pick up pebbles of odd shapes from the tuff which he found at the roadside. They had forms, as bizarre as never a man could invent, resembling animals or gruesome caricatured faces. These whitish stones reminded him of a dream: "I built in my dream a castle, a palatial grotto.” At the age of thirty he began to make his dream reality. He taught himself masonry. Nature gave him cornices, figures of giants, phallic symbols, Buddhas and Pharaohs. He improved on nature’s sculpture by adding weird forms upon weird forms. It took him 30 years to build and deco¬ rate the “Grotto,” the “Cascade,” the “Grave of the Druid,” and the “Pharaonic Grave.” Then he built his own tomb in the village churchyard. He tried to para¬ phrase historical styles according to his rather vague concepts. Although one may be reminded of exuberant Indian Baroque sculpture, the result was Postman Cheval’s own style. He left no inch of space empty. A decora¬ tive overall pattern of sculpture overgrows the long facade like parasitic plant life. Various large columns and giant figures give points of rest to the eye in the

house: the house of “Onituan,” i.e. Antonio Fiiarete. Filarete’s ideal city was crowned by a building in the shape of a mountain. A court surrounds two con¬ centric cylindrical towers, one within the other. They were adorned both on the inside and outside with pillared terraces and collonades. A steep staircase leads to the top of the tower of “Virtue,” hard but rewarding to climb, while another entrance leads down to the halls and caves of “Vice.” In front of these caves are mud holes with pigs burrowing in the dirt' The door leading into the “Hall of Vice” carries the inscription “Enter to indulge in pleasure, which afterwards you will regret.”

Kurt

Schwitters’

Cathedral

of

Erotic Misery,

maze of small forms. Cheval incised verses and captions at various places of the Grotto. Proudly he incised his work calender: “1872-1912 10,000 days, 93,000 hours. 33 years.” “Plus opiniatre que moi se mette a I’oeuvre.” “He who is more obstinate a man than I (may) go to work.” BRUNO TAUT (1880-1938) “Hail to transparent, the clear, the pure! Hail to the crystal! Higher and higher shall rise the floating form, the graceful, the sparkling, the flashing, the light! Hail to building eternal!” Bruno Taut, City Architect of Magdeburg, Ger¬ many, an official, a practical builder, wrote these dithyrambic words after World War I, in a defeated country. In the midst of a chaotic revolution and eco¬ nomic disaster, his architectural fantasy envisaged ideal buildings in a new and better world to come: dream architecture, domes of crystal to top mountain tops and houses with no other purpose than to be beautiful and to uplift the soul of the visitor. He de¬ signed an ideal city, with a star-shaped house of Friendship, shining like a star in the night, a salute to the stars in the sky. It would sound as the chime of a bell, it would be built of coloured prisms. There would be columns of prayer and columns of sorrow, austere black at the base, but changing into radiant gold in the height. Taut planned a house rotating on a sort of turntable according to the light of the sun. One of his dream houses was actually built, a house of glass, simple

and convincing in its construction. It was the high¬ light of the last architectural exhibit in Cologne be¬ fore World War I. He experimented with color in architecture, converting the drab and gray city of Magdeburg into a multicoloured maze. In Berlin he built 12,000 flats, not according to fantasy but according to the needs of middleclass people. He was a pioneer of modern functional hous¬ ing. He accepted a teaching position in Istambul, but death came before he reached his new field of action. THE IDEAL CITY NAMED SFORZINDA by ANTONIO AVERLINO FILARETE (1400-1470) Between 1460 and 1464, the Milanese architect, An¬ tonio Averlino, mainly known by his self-given hu¬ manistic name Fiiarete, wrote a treatise on archi¬ tecture, which reads in part like a didactical novel. He presents challenging ideas for an ideal city of tremendous dimensions to be built rapidly according to a working schedule. He plans the working hours of a manpower of 12,000 masters, seven assistants, 90,000 workmen, altogether 102,000 men, working under military supervision. The ideal city would be star¬ shaped. It would be a functional city, each building designed for its purpose: palaces for princes and bishops; living quarters for the burghers; schools ac¬ cording to new educational systems; animal parks; a tremendous hospital with hygienic devices. There would be water reservoirs, aquaducts and sewers. The entire city would easily be flooded for cleaning pur¬ poses. There would also be a Hall of Fame for out¬ standing artists, connected with the architect’s own

THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY ARCHITECT, ETIENNE LOUIS BOULLEE (1726-1799) and CLAUDENICHOLAS LEDOUX (1736-1806) It can be questioned whether architects trained in the rigorous discipline of Francois Blondel, even though considered revolutionary, would be able to swing themselves high enough into the clouds of imagination to fit into our pattern of fantastic archi¬ tecture. It is typical that in the Post-Baroque period in France, the most elementary solid forms appeared revolutionary. Boullee’s spiral tower, a truncated cone on a square base and his Newton Memorial, a perfect sphere had to remain projects on paper. However, Ledoux’s ideal city was built, at least partly. The story of these buildings has to be told as a “parallel in reverse” — if this expression is allowed, to the condemnation of the Watts Towers. Ledoux’s ideal city was planned and partly built around the Salt Works of Chaux between the villages of Arc and Senans in the French Conte. The French Government, conscious of its cultural heritage, main¬ tains a department for the preservation of monuments. Though Ledoux’s name at that time was fairly un¬ known, the owner of the Salt Works anticipated a “preservation order.” To forestall the governmental interference, he committed vandalism. He had Le¬ doux’s buildings dynamited in 1926. Only a few ruins are left. Ledoux’s theatre in Besancon (still existing) is rational. At that time it was new iri arrangement. Fantastic is only the way in which he rendered his impressive solution of a great building problem in an engraving. The interior of the theatre with its Palladian row of columns in the top rank and the semi¬ circle of the audience in the parquet is mirrored in a big eyeball. The eyelids and eyebrows, as if drawn from an ancient sculpture, give an almost surrealistic frame, emphasizing the purpose of the theatre: seeing. His house of the surveyors of the river is a symbol of man’s rule over the elements of nature. "It consists of a low prismatic block with open stairs on each side, and a superimposed horizontal semi-cylinder. Ledoux makes the river pass through the building so that the mighty vaulting is set astride the rushing water. Familiar with the architect’s inclination to dramatize form, we understand that the floods are to produce an uproar which stone alone cannot bring about.” Ledoux is considered the most imaginative of the architects of the Post-Baroque period, but his imagi¬ nation is interspersed with humanistic erudition and literary meaning. They are romantic allegories or “speaking architecture,” (architecture parlante). THE TATLIN TOWER A project designed by the constructivist painter Vladimir Tatlin in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Tatlin tower was designed to house a

4

radio station. The project was in the spotlight of at¬ tention in the years of political revolution after World War I. Artists and architects of many nations thought this was the time to find new shapes for a new world. Tatiin found a form both functional and symbolic for his construction: the spiral, a curve generating from one point, moving in a straight line around a fixed center, at the same time rising continuously upwards; motion expressed in architecture. The spiral expressed best the spirit of Tatlin's day, when new ideas arose from the fields of war-ruins and the debris of broken ideals. Remarkable in Tatlin's tower is the interpene¬ tration of inner and outer space. ANTONIO GAUDI (1852-1926) A cluster of four characteristic open work spires dominates the city of Barcelona. They soar to the sky from the facade of the Church of the Sagrada Familia, Gothic in spirit but hardly comparable to any style, a phenomenon in the age of functionalism. The open work spires above the facade of “Sagrada Familia” “break out into elaborate plastic finials whose multiplanar surfaces are covered with a music of broken tiling in brilliant colors . . . their note of free fantasy is raised in monumental scale . . . His “collages” of broken tiles have passages that remind one, when these are seen in isolation, of the work of such paint¬ ers as Klee or Ernst or even Leger . . . his whole ap¬ proach to the assembly of bits of broken crockery, often including fragments of the most vulgar and tasteless origin, parallels Dada and Surrealist prac¬ tices and most specifically the “Merzbilder of Schwitters.” The splendor of Gaudi’s surfaces leaves the spectator spellbound, and frequently detracts from the archi¬ tectural planning and significance of his buildings. Gaudi’s buildings move freely into space, often ignor¬ ing the borderline between sculpture and archi¬ tecture. The strength of Gaudi’s inner vision and emotion breaks forth disregarding rules and limita¬ tions of style. Gaudi is self-willed and inimitable, a unique apparition in the history of architecture.

5

THE MERZBAU OF KURT SCHWITTERS (1887-1947) Kurt Schwitters’ “Column” or “MERZbau,” also called “Cathedral of Erotic Misery” by its maker, has been destroyed by bombs during World War II. The house, in Hannover, Germany, Waldhausenstrasse 5, was en¬ tirely demolished, the debris swept away, and a new house built over the bomb crater. The column was the mast of Kurt Schwitters’ ship of imagination. Through twelve years I had watched it growing and breaking through the ceiling. Schwitters’ studio had to be converted into a duplex. The column was a three dimensional structure of wood, card¬ board, iron scraps, broken furniture and picture frames. The most heterogeneous materials were trans¬ formed into structural elements of an indoor tower, a sculptural architecture or architectural sculpture. When I saw it for the last time, it appeared more architectural, simplified in form and color to what today would, perhaps, be called “classic abstrac¬ tionism.” Kurt Schwitters believed firmly in abstract art, in functional architecture and construction. He called the expressionists “men who emptied their sour souls on canvas.” However, the column had not only formal but also expressive significance through literary and symbolic allusions. It was a depository of Schwitters’ own problems, a Cathedral built not only around his erotic misery, but around all joy and misery of his

life and time. There were cave-like openings hidden in the abstract structure, with secret doors of colored blocks. These secret doors were opened only to in¬ itiated friends. There was a “murderer’s cave," with a broken plaster cast of a female nude, stained bloody with lipstick or paint; there was a caricature abode of the Nibelungen; in one of the caves a small bottle of urine was solemnly displayed. This 3 dimensional document of Schwitters’ world appeared humorous in its details to many, but Schwitters’ world was austere, sad and even tragic, though it also was constructive, striving and gay. Kurt Schwitters had an indestructible sense of humor which covered his crevasses of misery. As Schwitters and his art matured the caves of the column were covered by architectural elements. It became a more formal architectural labyrinth or an ideal palace for imaginative thought to hide. BUCKMINSTER FULLER, 1896 Two decades - ago Buckminster Fuller’s projects were considered designs for a mathematical Utopia. Fuller was called a visionary crackpot. He got in trouble with the building code. His designs for houses were omnidirectional, translucent and light. This

sounds similar to Bruno Taut’s dithyrambic outbursts, however, Buckminster Fuller was a man of down to earth reality. If Sam Rodia built Instinctively and intuitively, creating a purposeless work of art by hand, which cannot be repeated, Buckminster Fuller constructs scientifically for industrial production in enormous quantities. He has a definite purpose: nothing less than rehousing an overpopulated world. Fuller’s constructions are translucent like Sam Rodia’s, but they are strictly geometrical, a multipli¬ cation of tetrahedrons, an orgy of tetrahedrons! The multiplication and combination of mathematical forms gives both uniformity and variety to his con¬ structions, a new beauty for a brave new world. Fuller uses standardized aircraft materials for all parts of his constructions, materials which combine rigidity with utmost lightness and economy. Fuller’s Utopic dreams of yesterday are in use today all over the earth. His geodesic domes are car¬ ried by air to sites in distant places, wherever air¬ craft hangars and shelters are needed. His domes appear in Afghanistan and near the poles. A pinned map. of the world shows their distribution, a worldvictory of the translucent, the light, the tensile strength.

References Postman Cheval: Pierre Gueguen. Architecture et Sculnture Naive. Le Palais de Facteur Cheval a Haute Rives. "Aujourd’hui, Art et Architecture” 2: 8:38-41 June 1936. Bruno Taut: Josef Ponten, Architektur die nicht gebaut wurde, Stugeart, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, 1923. dp. 136 ff 37Qf. Sforzinda: Antonio Averlino Filaretes Traktat ueber die Baukunst, herausgegeben von Dr. Wolfgang von Oettingen, Wien. Graes^er, 1890. Josef Ponten, Architektur die nicht gebaut wurde, Berlin,

Deutsche Verlagsanstalt. 1923. Boullee, and Ledoux: Emil Kaufmann. Three Revolutionary Archi¬ tects, Boullee, Ledoux and Lequeu, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 42, part 3, 1932. Philadelphia, The American Philosophical Society, October 1932. Tatlin: Gideon, S. Space, Time, Architecture. Cambridge, Harvard U. Press, 1914. Gaudi: Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Gaudi, New York, Museum of Modern Art (1957). Quotations derived from this booklet.

Buckminster Fuller

MALICE IN BLUE (Fragments for Sam) By Yoshiaki Tono blue, stripped off from the cruel Mediterranean blue, a drowned bird's retina peeled off the Catalan sky blue, fevered with B-type influenza in Tokyo blue, cut off by the silhouettes of the shabby buildings on Tenth Street blue, Hokusai imprisoned among the swelling waves blue, shot and frozen into crystal by a gaze of the rain-god Chac in Mayan ruins blue, glimpsed by SAS JET scattered among the glaciers of the North Pole blue, a beautiful negro boy conceals behind the iris blue bloody brain brimming over with the transparent malice blue bursting laughter of Cheshire cat swallowed Alice blue hates blue loves blue curses blue sighs blue hymns blue hangs blue goes blue balls blue poles blue microbes blue balloons blue kidneys blue nothing bloody recognition evokes a dialogue in blue leaves invisible flower-petals fallen from blue un deux trois quatre cinq six sept et blue evaporated cathedral crashed up to the firmament blue

Sam Francis: four drawings Ink Drawing," 1961.

"Ink Drawing." 1961.

"Ink Drawing," 1961.

Notes on the Nature of Joseph Cornell

^

Hi

T" ~ 1

Joseph Cornell, "Lunar Level £3 courtesy Ferus Gallery.

1

1

\ \

1

'

'

T

11

0^

.A

8x16x4", 1960. All photos

JOHN COPLANS Cornell* lives in Flushing, New York. He was born at Nyack, New York, in December, 1903. Little is known of the artist's early life, though a schoolboy interest in the theatre, history, and symbolist poetry is re¬ vealed. There is no record of college education or formal art training. There is little doubt that there was a special cul¬ tural climate in New York during his early years. The Armory show of 1913, which in turn produced the Steiglitz Gallery, the first avant-grade gallery in America, featured photography as much as painting. The climate of opinion at that time considered that photography, and the movie, would open a new ave¬ nue of illusionistic and fantastic art. In New Jersey, in about 1916, Mack Sennett formed the Vita-Graph Film Company. Also, during these early years, the first visit to America of Cornell’s favorite artist, Marcel Du: An exhibition of his work was given at the Ferus Gallery Los Angeles, during December, 1962.

champ.

Conner is a later spontaneous case.)

At the very inception of the film media replacing the theatre, Cornell sees that this is the new avenue to follow as an artist — fantasy and illusion not achiev¬ able on the live stage. Believing that it could be a tool of the highest art he becomes by choice a film artist. He collects one of the most complete libraries of films and still photographs of Chaplin, Sennett, etc. But the commercialism of this world soon cuts him off: nor, it should be noted, were any of the early film writers great artists. What he thought would open the doors to the furthest reaches of fantasy instead ruthlessly shaped the stereotyped movie star. (He has never met a movie star, yet reads about them avidly and has written about them. He published an essay in “View” in 1942 on Hedy Lamarr entitled “Enchanted Wan¬ derer.”) The only way he had been able to make movies himself was to re-edit and collage existing material, occasionally shooting a sequence. (Bruce

The earliest known work of Cornell outside of film is a work of about 1929, called “A Watchcase for Marcel Duchamp,” but there may have been earlier ones. We do not know exactly what he was doing before this time, but we do know that he had begun his incredible collection of documents, primarily 19th century, but ranging widely over other periods. These documents led to the most personal and visionary reconstruction of the history of art. Cornell's art appears to be based upon the notion that the most basic data on the nature of things is recorded in all manner of ephemera, that is, things short-lived and soon to be destroyed. Decayed and peeling plaster, postage stamps, theatre stubs, a fading photo, the movements of a hand of a clock, yellowing newsprint, emblems of nations and insignia of noble and powerful families that no longer exist,

Two broad categories of work: I. On the Nature of Things (in the Lucretian sense). A. Soap-Bubble Sets II. The oblique, symbolic Memorials and Portraits. A. The Taglioni Jewel Casket of 1942 The Casket, in the possession of the Museum of Modern Art in New York is labeled with the following anecdote: “On a moonlight night in the winter of 1835 the carriage of Marie Taglioni was halted by a Rus¬ sian highwayman and that enchanting creature com¬ manded to dance for this audience of one upon a panther's skin spread over the snow beneath the stars. From this actuality arose the legend that to keep alive the memory of this adventure so precious to her, Tag¬ lioni formed the habit of placing a piece of artificial ice in her jewel casket or dressing table where, melt¬ ing among the sparkling stones, there was evoked a hint of the atmosphere of the starlight heavens over the ice-covered landscape.” B. The Nearest Star (M.M.), of 1962. From the farthest star and physical reality to the most intensified personal identity — the Nearest Star: Marilyn Monroe.

A pillbox covered in shiny black and white lacquered paper. On the inside bottom of the pillbox is a drawn emblematic image of snail-shells, two chromed springs, a chromed ball-bearing and an actual snailshell. The combined image is another complex visual metaphor on phyllotaxis: the Golden Mean and Divine Proportion. Roll the ball through the springs into the snailshell; it’s also a game. This piece reminds us that Cornell, when asked the nature of his art, replied “They are games for mathematicians.’’ II. The First of the Soap-Bubble Sets (from the mid-'30’s). Evolving around the Galilean concept of the uni¬ verse, combined with a child’s sense of wonder. We are reminded that Einstein completed his Theory of Relativity in the year of Cornell's birth. III. The Memoriams (1930’s, 1940's). A. On individuals like Taglioni and Judy Tyler. B. On lovers and travelers and journeys in¬ volved with love, night and the stars. C. Those .that involve dancers. In this series of works, women are dancers, men are scientists, men and women are lovers, but dancers are also doves. Cornell has an encyclopedic knowledge of known and unknown ballet dancers of the last two hundred years. Other categories: The Forties, Fifties and Sixties. It is from the late thirties to the present that Cornell has really flowered, though the war seemed to inter¬ rupt his investigations. I. The Miniature Palaces. II. The Natural History Museums A. The Pharmacies. B. The Habitat Settings: aquariums, butter¬ flies, bees, rabbits, birds. a. Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery (1939-43). Usually Cornell would ignore evil or violence. Here, however, is a bullet hole through the glass. On one level, each different exotic bird might represent one of the great powers at war. Behind the birds, who are wounded, are splashes of colors (various bloods). The birds are still alive, they bleed, yet Cornell has a desperate hope for their survival. The bundle of news¬ papers and shot-off feathers is the droppings at the bottom of the box. III. Back to the Nature of Things A. Sand Fountains. B. Sand Map Games. C. Map Toys. IV. The Hotel and Night Skies. A. Hotel (Night Sky), 1952. Through the window, its panes divided like a gunsight, the Most Distant Star.

Other categories: The Thirties and Forties: I. Time and Space (from 1929 to the mid-’30’s). A. A Watch-Case for Marcel Duchamp. The watch-case contains a little stack of layer upon layer of pictures. Time and movement revealed through a matrix of images. B. Four Wooden Cylindrical Chemical Con¬ tainers. When opened, a similar compass is revealed in each container, and, as usual when compasses are placed close to each other, each points to a dissimilar North. This piece is a complicated visual metaphor: four containers of matter, Air, Earth, Fire and Water, opened, define space. C. Untitled Object (1933).

V. The Space Object Boxes A. Smiling Sun. B. Lunar Level. C. Other Planets. D. A return to Cosmic Systems. a. The Sailing Ship (1961). The cordial glass holds the earth in place. An astronomer’s explanation of the universe is as rude and elementary a conceit as Cornell's cordial glass: one stands for the other. The ball on the tracks is a planet in orbit. The face has tide tables, charts, the blue front has wavy patterns like the sea. The traveler’s hand reaches out for water. b. Lunar Level #3 (1960). The loose balls at the bottom of the box are satellites as yet unreleased. This work, like many others, is a still-life arrangement that corresponds to the Dutch 17th-century painters’

soap bubbles (ephemeral planetary spheres that last a few seconds). A Theatre of Things, doomed to vanish, change or be destroyed. The last movie that he did was when the Third Avenue El was torn down in the forties. It had been a dramatic means of transport for the populace of the city. What was originally a shining, new, and clean marvel of engineering shifted from a romantic land¬ mark of New York City life into depressing squalor. Youthful beauty to old age, decay, and eventual disso¬ lution. Cornell arranged to have a documentary made before it perished. In understanding the importance of ephemera to Cornell it should be noted that he has steadfastly refused the ordinary avenues of publication, such as catalogs and books, in preference to the throw-away leaflet or the magazine. Cornell sees man in a theatre of formal design and elegance, like ballet. He loves the formality of the imaginative theatre as much as the formality of sci¬ ence, all of which he sees as poetic revelation where the most banal and trivial facts often carry the reality of the matter, in contrast to the historians, who are most terribly destructive. In their attempt to strip away the trivia they are left with hollow truths.

use of navigation instruments and charts on walls. The window to the sky becomes a meteorologist’s chart of the different types of clouds at various levels in the sky, the flags on the driftwood show which way the wind is blowing. c. To the Nearest Star, M.M. (1962). The symbol of the rings is that one might start at any point to follow the pathway and continuously come back to, and re¬ pass, any chosen beginning. It is Cornell’s most recur¬ rent symbol, and corresponds exactly with the Einsteinian sense of infinity (space curves and returns, retracing itself, giving a sense of ultimate totality and self-containment, as revealed not in Oriental mys¬ ticism but in Western physics and astronomy). Cor¬ nell’s drive to establish notebooks and journals of data have overtones of the Complete Renaissance Man. He signs his boxes like Leonardo da Vinci, in mirror-writing, and, like da Vinci, is struck with curiosity. But he is not a rationalist, designs no war machines, having a totally gentle sensibility. Nor is there room for evil in Cornell’s world. He wants to observe, document and record, but change nothing. Each box and each thing within is put together in the most simple and direct way, with screws, nails and glue. Everything looks innocent and true. The peeling decayed plaster walls carry the history of generations — they come from old buildings. He is a key assembler, a true assemblage artist, earlier and purer than Dubuffet. The glass front divides Cornell’s world from ours, yet at the same time we can enter into it without difficulty. Our eyes, which peer into the boxes, are the basic scientific instrument, the hand holding the boxes is the basic tool. The mind binds and links the two together. Cornell constantly re¬ echoes universals, his boxes highlight the continuity of life, awareness and knowledge of how the drama of decay makes it bitter-sweet. The pathways of move¬ ment and change through the flow of time, stars in the firmament doomed to burn out, and earthly ones, like Marilyn Monroe, fall too, and in falling are extinguished. Cornell would love to keep everything he makes, it is important for him to have them: a. They are part of a total universe he doesn’t like to disturb. b. He continuously re-works in order to improve and perfect. c. When he does release them, he wants them to go to people who would cherish them — he hates the idea of them being in indifferent hands. He is heartstricken at the present commerciality of the art world. He does not regard his work as products, but datum. ■ From newspaper clippings dated 1871 and printed as curiosa we learn of an American child becoming so attached to an abandoned chinoiserie while visiting France that her parents arranged for its removal and establishment in her native New Eng¬ land meadows. In the glistening sphere the little proprietress, reared in a severe atmosphere of scientific research, became enamoured of the rarified realms of constellations, balloons, and distant panoramas bathed in light, and drew upon her background to perform her own experiments, mir¬ acles of ingenuity and poetry. by Joseph Cornell. (View, Jan., 1943)

KANDINSKY The Guggenheim retrospective raises questions concerning Kandinsky’s contribution as artist and as theoretician. HILTON KRAMER Everything would now seem to favor a high estimate of the art of Kandinsky. From the historical point of view, he was an innovator of great importance. He was, after all, one of the two or three key figures in the creation of modern non-figurative painting. This in itself is enough to guarantee his oeuvre a permanent place in the modernist canon, for the whole tendency of contemporary criticism and art-historical scholar¬ ship has been to identify artistic achievement with stylistic innovation. But in Kandinsky's case, our in¬ terest is not only —or exclusively — historical. It extends to his influence on the recent, and perhaps even the present, course of art. His innovations, how¬ ever one may now want to judge the esthetic quality of the individual works in which they appeared, have remained consequential. He is, if not the father, then at least the grandfather of two styles that still occupy dominant positions in current art. He was the first of the abstract expressionists, and he was also an early — though not the earliest or most distinguished — ex¬ ponent of that tight, so-called “geometrical” abstrac¬ tion that has lately been revived with some success. His art thus enjoys a claim that is both historical and, as the French say, “actuel.” Kandinsky’s career, moreover, was of a kind that makes his name nearly ubiquitous in the annals of modern painting. Born in Russia, he played an active part in the development of modern art in his native country during the brief but intense period immedi¬ ately following the Revolution when, for a few bright years, modernism in the arts was welcomed by the Bolsheviks as an instrument and companion to politi¬ cal revolution. (This relatively brief phase of Kandin¬ sky’s career was more interesting for what the artist contributed to the Soviet cultural scene in the first stage of its revolutionary ferment than for what it contributed to his art, but even this phase has lately assumed a new interest and importance in the light of recent attempts to revive abstract art —and mod¬ ernism generally—in the Soviet Union, for in any such revival Kandinsky inevitably figures as a mentor and exemplar.) More important from the point of view of Kandinsky’s creative development, however, were the two quite separate and distinct careers he enjoyed in Germany before and after the Russian Revolution. The first of these, beginning with his years as an art student in Munich at the turn of the century (when he first met Klee) and deeply marked by his associa¬ tion with Gabriele Munter, the German painter who was his mistress in this period, and his fellow Russian artists, Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, culminated in “Der Blaue Reiter’’ exhibitions of 1911-12. The second, dating from 1922 when he joined the Bauhaus at Weimar, ended in 1933 when the Nazis closed the Bauhaus and Kandinsky settled in Paris. These two German periods constitute the real locus of Kandinsky's creative achievement, but his influ¬ ence extended beyond them, of course. He remained in Paris until his death in 1944, and had his disciples there. And owing to the large collection of his works

assembled by the Baroness Rebay for the late Solo¬ mon R. Guggenheim, a collection that formed the nucleus and raison d’etre for the original Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York (now the S. R. Guggenheim Museum), Kandinsky's art had begun to affect the course of American painting even before his death. By turn a Russian, a German, and a French citizen, and the only modern artist to have a museum more or less consecrated to his work and his the¬ ories in the United States, Kandinsky bestrides the international art scene in this century as only a very few other painters have done. In view of such impressive credentials, it may seem churlish to raise questions about the character and quality of Kandinsky's achievement. Yet the very enormity of Kandinsky’s career and influence and the exalted status his works now enjoy among the official custodians of modern painting make such questions imperative —and indeed, overdue. Was Kandinsky a great painter? Was he even a good painter? Was there perhaps a basic discrepancy between his ideas and his ability to realize them on canvas? Was he at his best as an abstractionist, as we have been led to suppose, or are his purest works, to be found, para¬ doxically, among his representational paintings? These are not the questions we are in the habit of asking about modern painters. It is enough, usually, to define an artist’s contribution to the modern movement, and to explicate the morphology of that contribution. If, as in Kandinsky’s case, the artistic contribution de¬ rived from, or was at least accompanied by, an inter¬ esting and original body of ideas, then the lines of definition and explication will follow the contours of the artist’s thought, and pictures that most fully ex¬ emplify—one might almost say illustrate — basic doctrine will be judged the most successful and char¬ acteristic. This, at any rate, has been the prevailing critical practice, and Kandinsky has been one of its chief beneficiaries. The view of Kandinsky that Mr. Thomas M. Messer, the director of the Guggenheim Museum, has now given us in two mammoth exhibitions* conforms to this practice of turning the artist's oeuvre into a kind of pedagogical allegory of his ideas and their place in art history. Now it may be that any really ambitious survey of Kandinsky’s painting on the scale Mr. Messer has undertaken would have to follow this course. The bulk of Kandinsky’s art is painting of a kind that would be difficult, perhaps impossible, to defend on purely pictorial grounds, and I know of no serious critic who has even attempted to defend it on such grounds. The defense is made for the most part on points of general esthetics and art history — which is to say, in those areas where Kandinsky really does shine as a brilliant and original figure; and it is usually assumed — erro¬

*The larger of these exhibitions will travel to Paris t Hague, and Basel after its showing at the Guggen’he Museum in New York. The smaller, after initial showin at Pasadena, San Francisco, and Portland, will be seen seven other museums across the country. Both exhibitio were selected by Mr. Messer.

neously, I believe —that the force and originality of the artist's mind will somehow explain away the defi¬ ciencies that mark his performance as a painter. This approach to Kandinsky has sometimes resulted in interesting and even eloquent writing on his accom¬ plishments, but it places the organizer of a Kandinsky exhibition in the difficult position of having to pro¬ duce a body of work that will live up to the extrava¬ gant expectations aroused by the official literature. By and large, Kandinsky comes off better as an artist written about than as one seen, and this is undoubt¬ edly one of the reasons — there are others — why Mr. Messer has taken his lead from the literature (and the view of art implicit in it) rather than from the art itself. As everyone who has read "Concerning the Spiritual in Art” knows, Kandinsky was immensely knowledgable about pictorial problems. Yet unlike Mondrian, an artist whose development was in so many other respects similar to Kandinsky’s, Kandinsky never for¬ mulated a viable pictorial principle as the basis for his non-figurative painting. He explicitly held back from such a formulation in writing his famous and influential treatise, and the intellectual diffidence reflected in that document is also clearly visible in the way he painted his early non-figurative pictures. In his treatise Kandinsky wrote: “One of the first steps away from representation and toward abstraction was, in the pictorial sense, the exclusion of the third di¬ mension, i.e., the tendency to keep the picture on a single plane. Modeling was abandoned. In this way the concrete object was made more abstract, and an important step forward was achieved—this step for¬ ward has, however, had the effect of limiting the pos¬ sibilities of painting to the actual surface of the can¬ vas: and thus painting acquired another material limit.” Reading this, one is reminded of Braque’s maxim: “Any acquisition is accompanied by an equiv¬ alent loss; that is the law of compensation.” But this “law of compensation” was not one that Kandinsky could accept. He thus differed from later exponents of abstraction in his deep desire to carry over into non-figurative art all the depth (for Kandinsky, it was not only spatial but spiritual) and pictorial complexity he admired in the great representational painting of the past. It was not a further “material limit” he sought, but an expansion of painting’s spiritual and pictorial resources. If one feels a certain irony and pathos in reading “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” today, a half-century after its publication, it is be¬ cause one now sees with what eloquent and prophetic reluctance its author did indeed usher in a new era in pictorial values. For Kandinsky was emphatic in rejecting the idea of "a single plane.” “Any attempt to free painting from this material limitation, together with the striv¬ ing after a new form of composition,” he wrote, “must concern itself first of all with the destruction of the theory of one single surface...” And yet he was equally unwilling to submit his art, and painting gen¬ erally, to the only new mode of pictorial syntax that

10

Composition VII, ^186, 783/4xll8l/a", 1913.

11

promised to keep painting both abstract and threedimensional: which is to say, he was equally set against the practice of cubism. “Out of composition in flat triangles has developed a composition with plastic three-dimensional triangles, that is to say, with pyramids; and this is cubism. But here a ten¬ dency has arisen towards inertia, towards a concen¬ tration on form for its own sake, and consequently once more a reduction of potential values.” Eventu¬ ally, of course, Kandinsky did submit his art both to the tenets of cubism and to what he described (accurately) as “pure patterning.” Eventually he did accept, to a degree, the very “reductions” he had set his mind against in writing “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” but he did so with diffidence and without consistent success. This diffidence had two causes, I believe. The larg¬ er, or at least the more “spiritual,” cause (and Kan¬ dinsky himself would have considered this the larger, at least in his “Blaue Reiter” period) was his unwill¬ ingness to concede the possibility that in abandoning “external nature” as a source of visual form, he might be imposing a radical limitation on the painter’s for¬ mal and expressive repertory. Everything in the realm of intellect and the arts that absorbed Kandinsky’s interest in the first decade of the century led him to

believe otherwise. The theosophist belief in the su¬ premacy of spiritual values over the material world; the new scientific theories that swept away conven¬ tional notions of matter and energy; and the whole tendency of 19th-century symbolist poetry and music to eschew naturalism in favor of a more transcen¬ dental concept of reality: these developments in phil¬ osophy, science, and the arts, abetted by Kandinsky’s own mystical turn of mind, were more than enough to convince him that a similar abandonment of mate¬ rialism (that is, “external nature”) in the art of paint¬ ing would inevitably• bring greater expressive possi¬ bilities in its wake. “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” is, in fact, a meditation on these possibilities, just‘as his early "Improvisations” and “Compositions” are attempts to explore ways of realizing them. But “Con¬ cerning the Spiritual in Art" is also a dialectical exer¬ cise in which this meditation is combined with an analysis of the new pictorial practices that were then emerging in the works of Matisse and Picasso — prac¬ tices that Kandinsky both admired and feared. His keen pictorial intelligence responded to the strength and originality with which the Parisian masters were developing styles that effectively challenged the very naturalism that had at all costs to be rejected, and yet his "spiritual” ideology — the conviction that the

turn toward abstraction should not involve the jet¬ tisoning of painting’s traditional resources but instead transform them into an even larger and more powerful artistic instrument —resulted in a vigorous warning against the two directions (on the one hand, “a con¬ centration on form for its own sake,” and on the other, “pure patterning”) in which he correctly saw cubism and fauvism respectively moving. The radical in Kan¬ dinsky was thus held at bay by the traditionalist. The second cause of Kandinsky’s diffidence in the face of these cubist and fauvist innovations was di¬ rectly connected with this ideological reluctance to accept the “reductions” they seemed to make impera¬ tive: he lacked any syntactical principle of his own that might have preserved painting against this feared reduction of means. He might resist for a while the new syntactical procedures of the Parisian school, but he had no radically new alternative to offer in their place. Conceptually, his art remained an amal¬ gam of received ideas. What he did effect in his own painting was a synthesis of the new forms that were emerging from cubist and fauvist painting (and from the expressionist painting that more or less merged with fauvism outside France and that Kandinsky him¬ self practiced for a time with great success) with the traditional syntax of 19th-century painting, and as

Levels, #452, 22Y4xl6", 1929.

it happened, this conjunction of the new and the old gave the appearance of being more radical than it actually was. Kandinsky nowhere admits this compro¬ mise explicitly in his writings, but he hints at it, and it is in any case clearly evident in his painting. In attempting to define the kind of pictorial construc¬ tion he aspired to as an alternative to Parisian prac¬ tice, he wrote: “It is not obvious geometrical con¬ figurations that will be the richest in possibilities, but hidden ones, emerging unnoticed from the canvas and meant for the soul rather than the eye.” The notion that a painting’s syntactical principle might pass ‘unnoticed” sounds rather bizarre, if not indeed nos¬ talgic, from our present vantage-point in the history of abstract painting. Bizarre or not, however, the no¬ tion is a significant measure of Kandinsky’s basic equivocation as an abstract artist. One can certainly admire —as I do — Kandinsky’s refusal to reduce painting to its barest syntactical components, for it was fundamentally the refusal of a man of exquisite culture and intelligence to betray his artistic inheritance with facile notions (now so widely accepted) of “less” being “more.” One can sym¬ pathize with this yearning for a high cultural ideal, but all the sympathy in the world cannot improve the quality of the pictures Kandinsky painted under its influence. In effect, Kandinsky repopulated the ro¬ mantic, impressionist, and post-impressionist land¬ scape space of 19th-century painting with at first symbolic and then totally abstract —and often illdefined— forms. This was what his abstract expres¬ sionism came to; his “hidden construction” consisted of putting some new wine, as it were, in a familiar

bottle. The question arises, then, as to exactly how this curious synthesis of old and new ideas became as fateful for modern painting as, ultimately, it did. A clue to the answer to this question can be found per¬ haps in Kandinsky’s suggestion that his style was intended for “the soul rather than the eye.” Kandin¬ sky’s concept of “soul” was indeed too disembodied, too vague and immaterial, to be pictorially useful, and so in practice its visual habitat nearly always resem¬ bled some variety of 19th-century landscape space, but a more imaginative painter, namely Miro, working out of the psychoanalytic topography of surrealism, turned this territory of the “soul” into the dreamlike landscape of the subconscious. It was by way of Miro’s highly individual use of surrealism, with its erotic fantasy and symbolic drama, that Kandinsky’s “spiri¬ tual” universe was re-materialized, so to speak, and thus at last able to assume a radically new structure for pictorial purposes, and the way then led from Miro to Gorky and Pollock and many others. As an innovator, then, Kandinsky was a more equiv¬ ocal figure than has generally been assumed. (Only Clement Greenberg, in an essay reprinted in “Art and Culture,” has really confronted the issue.) And his failures as a painter are to a large degree — though not wholly — based on this equivocation. But, of course, his works were not all failures. The best of Kandinsky’s abstract paintings are, I think, the four panels on the “Seasons,” painted in 1914 and shown as a group in the Guggenheim show. (Two of these paintings, “Spring” and “Summer,” are now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, the other

two, “Autumn” and “Winter” being part of the Gug¬ genheim’s permanent collection.) This series is still dominated by the imagery and “feel” of post-impres¬ sionist landscape art, but the imagery is now far more compressed and summarized than is usual with Kan¬ dinsky; this is particularly so in the “Autumn” and “Winter” panels. The paint itself forms a more unified and continuous “skin” without degenerating into the feared "patterning,” and the use of color is more consistent and lyrical, more sensuous and confident. There is, too, less of that graphic scaffolding which is so painfully evident in most of Kandinsky's abstract expressionist paintings — fewer of those disfiguring black lines that measure the exact distance between the artist’s elevated painterly intention and his usu¬ ally mundane ability to realize it on canvas. The only other oil painting that approached the success of this series was the huge "Composition VII” (1913), one of the seven paintings borrowed from the Soviet Union for the New York exhibition and, like the four “Sea¬ sons” panels, an obvious attempt to sum up and consolidate the earlier “Improvisations” and “Com¬ positions” into a definitive statement. Perhaps there was something about the vertical format of the “Seasons” series that liberated Kandinsky from a certain pictorial banality that still plagues even this “Composition VII." Whatever the reason, they stand out as Kandinsky’s highest achievement in abstract painting. The only other abstract work in the Guggenheim exhibition that could be favorably compared with this series was to be found among the watercolors and graphics. As a general rule, Kandinsky was more

12

Street in Murnau (Street in Murnau with Women). 28x38 ya", 1908.

13

at ease —and more successful — with the decorative potentialities of abstraction in manipulating the color transparencies characteristic of the watercolor me¬ dium and in the explicitly graphic character of the woodcut. The flat white page of the paper provided him at the start, perhaps, with a kind of space, at once shallow and “infinite,” that he could not bring himself to accept, or create, in approaching the can¬ vas. In particular, the “Untitled Watercolor” dated “1910” on its face but now generally believed to have been painted in 1913, is one of Kandinsky’s supreme artistic successes as an abstractionist, and it has a more immediate, up-to-the-minute relevance to cur¬ rent abstract painting than any single oil in the New York exhibition. The painters who now “stain" their unprepared canvases with thinned, irregular washes of oil pigment in an all-over design, using oil as if it were watercolor, all follow in the wake of this extraordinary little work. But Kandinsky himself never really followed through on the principle of composi¬ tion inherent in the work. When we turn from the work of Kandinsky’s first German period, which ended with the outbreak of World War I, and examine the work of his second which commenced with his return from Russia in 1922, we are again reminded of what consequences followed from the artist’s basic failure to commit his art to a structural principle that would unite its form and content into a single coherent statement. In the work of the twenties, it is a case of everything chang¬ ing and everything remaining the same. The shape of the forms in the paintings of this period are greatly simplified and clarified, but they are basically the same forms as before, only now purified into graphic and geometrical essences and left to drift in the same indeterminate space. As an exponent of tight, geo¬ metrical abstraction, Kandinsky was always a mud¬ dler, earnestly filling naturalistic space with abstract motifs, and then jamming these disparate materials into some precarious coherence by sheer will. These

pictures are pretty dismal for the most part, but they too have had a widespread influence, as one can see from looking through the old catalogs of the Amer¬ ican Abstract Artists and from those surveys of minor Parisian abstract artists that Michel Seuphor has assembled from time to time. There remains a kind of academic abstraction in Germany even today — all “cosmos” and no art —that takes its cue directly from this phase of Kandinsky's oeuvre. For myself, the main interest of the later works in the New York exhibition (from the late twenties and the thirties) was the sense I had of the influence some of the more diagrammatic abstractions must have had not only on painting but, more importantly, on the constructivist and surrealist sculpture that began to take shape in New York in the thirties. Works like “Levels, No. 452” (1929) and “Development Upwards, No. 596” (1934), both in the Guggenheim collection, lead directly to a kind of sculpture that has occupied David Smith, for example, since the thirties. Both of these paintings are, in fact, graphic illustrations of abstract objects that could never become wholly realized, plastically, until an artist like Smith had found a way to translate them into the technology of open-space sculpture. All in all, the view of Kandinsky that Mr. Messer has given us is of this international master — if mas¬ ter he is — of the modern movement, the prophet of abstract art for whom so persuasive a case can be made so long as we do not look too closely at the indi¬ vidual works. And this is pretty much the Kandinsky that everyone seems to want just now — a benevolent grandfather who can at one stroke be made both to support current esthetic dogma and yet leave us with the heady satisfaction of knowing that we can do this sort of thing much better nowadays. (I think we can, and do.) But there is, alas, another Kandinsky who barely makes an appearance in the Guggenheim exhi¬ bition, and who remains, by and large, an unknown painter to everyone who has not seen the fine collec¬

tion of paintings that Gabriele Munter donated only a few years ago to the Stadtische Galerie in Munich. That Kandinsky does not figure as an eminence in our art histories, but he was an uncommonly good painter. In the years 1904-1909, especially, he produced works of a quality that are exceptional in his entire oeuvre. They are mainly small landscapes painted from nature, post-impressionist in format and expres¬ sionist in feeling, and executed with a verve and con¬ fidence nowhere else to be seen in Kandinsky’s long development. Historically, they are interesting be¬ cause they form the basis of the abstract expres¬ sionist landscapes that grew directly out of them, but artistically they remain superior to all but a few of the abstract works. (Only the "Seasons” series equals them in quality.) In the Guggenheim show, only one painting — "Beach Baskets in Holland" (1904) — represented Kan¬ dinsky at his best in this period. Another, “Street in Murnau” (1908), was a good example of his method at the time, but not itself a first-rate picture; Kandinsky had difficulty with figures. The virtual omission of this important body of work cannot be attributed altogether to a narrow conception of Kandinsky’s real gifts as a painter, though such a conception undoubt¬ edly played its part. The delicate matter of Kandin¬ sky's involvement with Gabriele Munter must cer¬ tainly have been an obstacle to the organizer of an exhibition that required the generous cooperation of Kandinsky's widow, Mme Nina Kandinsky, the Russian woman Kandinsky married after his break with Munter and his return to Russia during the Revolution. My own view, after seeing the Kandinskys in Munich last year and also the large group of Munter’s own paintings that are shown in the same museum, is that Kandinsky's life and work cannot be fully under¬ stood without a more detailed understanding of this so-called “Murnau period" than we have been given. This was the period when Kandinsky lived with Mun¬ ter in the house at Murnau where they often had as guests, for extended periods, Jawlensky and von Werefkin. The paintings that these four artists did at that time, and especially those of Kandinsky and Munter, are often as close in subject, method, and feeling as the pictures Picasso and Braque painted in the first phase of cubism. This was, moreover, the only time in Kandinsky’s adult life when, as a man, he was rela¬ tively free of respectability and worldly cares and, as an artist, he was an earthy and robust painter of the natural world. Fortunately, the omission of this work from the Guggenheim show was to some degree corrected by the ambitious survey of the “Blaue Reiter" group that the Leonard Hutton Galleries staged to coincide with the Kandinsky exhibition. A good deal of the exhibition had only an historical interest (twenty-two painters were represented, including Schoenberg, the composer, who was much interested in Kandinsky’s ideas but who was not much of a painter), but it did include four good works of Kandinsky’s Murnau period together with a fine selection of Munter’s paintings done at the same time. These few works, seen in the context of their own period and subject-matter, gave one a more intimate glimpse of Kandinsky’s sensi¬ bility than was possible in the selection of early pic¬ tures in the Guggenheim survey. And they left one with a nagging sense of how little we have yet under¬ stood about the inner life of the artist whose “spiri¬ tual” achievement has been set before us in such exhausting detail. ■

Anti-Sensibility Painting An early exhibitor of the controversial “Pop Art” presents his case.

Tom Wesselman, “Still Life,” 4'x5V2', 1962. Green Gallery, New York. (Collection Mr. and Mrs. Charles Buckwalter.)

Roy Lichtenstein, “NoNox,” pencil on paper, 25V2X19", 1862. Leo Castelli Gallery.

ITALIAN

IVAN C. KARP The American urban landscape is fantastically ugly. Detroit is a fine example. The packaged horror of the super shopping center inspires at its worst (or best) a degree of revulsion instructive to the open eye. All others flee to Venice. The Common Image Artist observes the landscape with its accoutrements and provokes a consummately generous view of a generally monstrous spectacle. His philosophy is that all things are beautiful, but some things are more beautiful than others. What is “more” beautiful is imbued with the glorious nimbus of reve¬ lation. This is his subject. At its best Common Image Art violates various established sentiments of the ar¬ tist. By rendering visible the despicable without sen¬ sibility, it sets aside the precept that the means may justify the subject. The poetry is invisible. It is the fact of the picture itself which is the poetry. There is no startling pictorial apparatus employed to seduce the eye. The forms are locked into place and the col¬ ors are bright. The design is simple, almost simple minded. But the simple mindedness is vicious. It grates against the nerves.

The greatest art is unfriendly to begin with. Com¬ mon Image Art is downright hostile. Its characters and objects are unabashedly egotistical and self-re¬ liant. They do not invite contemplation. The style is happily retrograde and thrillingly insensitive (a curi¬ ous advance). Red, Yellow, and Blue have been seen before for all they are worth. In Common Image Art they are seen once again. It is too much to endure, like a steel fist pressing in the face. The formulations of the commercial artist are deeply antagonistic to the fine arts. In his manipula¬ tions of significant form the tricky, commercial con¬ ventions accrue. These conventions are a despoilation of inspired invention. But they are, in the dis¬ tillations of profound observations, a fecund fund for insight into the style that represents an epoch. In Common Image Painting a particular and certainly peculiar moment in time is perfectly revealed in a strangely timeless mode by encompassing the con¬ ventions of commercial and cartoon imagery. Thus it engages the total panorama of visible evidence. The worthy subject is struck down once and for all. Nothing that is seen is too base to look at, as every

form and space is suddenly interconnected. The mer¬ ciless matchbook is lying in a vernal meadow, beside a brook near a frozen custard stand and funny papers on the chair in a house full of paintings by Inness. Why Common Image Painting is remarkable at this time is because it proceeds from the artist's ecstasy of vision. The best of recent abstract painting, the works of Louis, Noland, Kelly, result from a total in¬ ward turning, a blindness to the spectacle, and in that they are excessively effete, refined, and genteel. No¬ land’s recent show in New York was elegant and lean; the grandeur was missing. The vortex and target are, like the suspension bridge, infallible as form. But Noland's targets have crossed all their rivers. The paintings of Louis are not a civilization. For all the exquisite tonalites, expansiveness, and scale, the works are timorous and kindly. Art without fierceness is only restful. It never agitates or beckons. Even Claude is fierce. When the painter eschews the expe¬ rience of wonderment at the spectacle he becomes a nervous pattern maker. Kelly’s paintings are a gran¬ diose rearrangement of small, neat discoveries which derive from the inward turning against the pain and

Andy Warhol, “Silver Disaster #6,” 42x56", 1963. Stable Gallery, New York.

James Rosenquist, “Two 59 People,” ca. 5'x7'. Collection Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University.

pleasure of the spectacle. Abstract Art at the moment is onanistic, an art of special effects. The artist uses his vision after the picture is made. The paintings of Pollock, Kline, and de Kooning begin with astonish¬ ment at something outside the self; they are of the phenomena and the energy of the environment. Euro¬ pean art is tired because the landscape and spectacle are depleted of interest for the painter. Common Image painting, in extracting, amplifying, and re-poising the conventions of the commercial arts, reveals the psychological and stylistic temperament of an age before it is visible. Nostalgia becomes in¬ stantaneous. Lichtenstein paints popular subjects of the forties and fifties which is, as an age, still invisi¬ ble without Lichtenstein. The “Yellow Girl” is timeless in her horror. In her conceit and vacuity she is hateful forever. In “No Nox,” the Gas Station Attendant is a symbol of himself, vile in his uninvolved stupidity. He is created of hard, cold lines that do not derive from abstraction; a severe classicism, no sensitivity, no poetics, no mush. Rosenquist depicts the Gothic of the Thirties in vomity tones and brilliant, cruel com¬ positions. The toast is stale and the smile is not for us. Although he manifests a certain artfulness that is akin to surrealism, the distance of his subjects from the viewer sustains the nice, cold, signboard clarity. Wesselman’s subjects are the present moment in com¬ mercial art. At his best he is bright and brutal, like the aluminum jackets of cheap skyscrapers. The jux¬ tapositions are crucial. He has proven with a subtle maneuver that the immense vulgarity of advertising color and form, separated from their natural habitat, is sufficient to reveal its hidden charms. The giant economy size can of Del Monte asparagus is a glory unto itself. The plastic corn with butter induces nau¬ sea and trembling. These objects are ghastly and won¬ derful at once, too horrible for words, a fearful joy. Warhol’s art is that of innocent wonderment. When he avoids lyricism his repetitions achieve a grave sim¬ plicity. The “Electric Chair” painting in silver is an apogee of violence. It has no literary content. (The “Silence" sign insists.) The vertical zone on the right is numb and reflective, an abstraction of the image on the left. Sensitivity is a bore. Common Image painting is an art of calm, profound observation and humorous won¬ derment without sensibility. It does not criticize. It only records. The attitude of the Common Image paint¬ er is whimsical and slightly ironical. The environment is overwhelming, and thus he observes it. He must maintain the sense of the monumentally bizarre with¬ out surrealism or else he will defeat his art, just as Abstract Expressionism was winded by lyricism. The Abstract painters are obliged to locate the timeless symbols from their environment before they can con¬ ceive a revolutionary vitality akin to Common Image Art. The purging of poetic sensations in painting for an aggressive classicism marks the end of Impres¬ sionist oozings. For all the perversities, horrors, and doomist regalia in the excellent private works of Lind¬ ner, Samaras, Bontecou, and Conner, the American ar¬ tists are inclined to bold affirmations. Rauschenberg’s art is the ideal symptom of these high spirits. He is a prince of imagination, that critical ingredient, and bountiful source of inspiration. Common Image paint¬ ing is an affirmation of the pleasure of seeing, and although it was supposed to have expired at five o’clock on a Friday a long time ago, it will surely con¬ tinue until a petty academy vetoes its puissance. Al¬ ready it is a monument and possibly a bridge to a splendid new Romanticism. ■

An Open Letter to an Art Critic "It has always been my hope to create a free place or area of life where an idea can transcend politics, ambition and commerce.”

Clyfford Still