AIDS and religious practice in Africa 9789004164000, 9789047442691

140 91 77MB

English Pages [416] Year 2009

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Frontmatter

Introduction: Searching for Pathways in a Landscape of Death: Religion and AIDS in Africa (Felicitas Becker & P. Wenzel Geissler, page 1)

NEW DEPARTURES IN CHRISTIAN CONGREGATIONS OF LONG STANDING

The Rise of Occult Powers, AIDS and the Roman Catholic Church in Western Uganda (Heike Behrend, page 29)

Christian Salvation and Luo Tradition: Arguments of Faith in a Time of Death in Western Kenya (Ruth Prince, page 49)

The New Wives of Christ: Paradoxes and Potentials in the Remaking of Widow Lives in Uganda (Catrine Christiansen, page 85)

CONVERGENCES AND CONTRASTS IN MUSLIMS' RESPONSES

AIDS and the Power of God: Narratives of Decline and Coping Strategies in Zanzibar (Nadine Beckmann, page 119)

Competing Explanations and Treatment Choices: Muslims, AIDS and ARVs in Tanzania (Felicitas Becker, page 155)

'Muslims Have Instructions': HIV/AIDS, Modernity and Islamic Religious Education in Kisumu, Kenya (Jonas Svensson, page 189)

PENTECOSTAL CONGREGATIONS BETWEEN FAITH HEALING AND CONDEMNATION

'Keeping Up Appearances': Sex and Religion amongst University Students in Uganda (Jo Sadgrove, page 223)

Healing the Wounds of Modernity: Salvation, Community and Care in a Neo-Pentecostal Church in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania (Hansjörg Dilger, page 255)

Gloves in Times of AIDS: Pentecostalism, Hair and Social Distancing in Botswana (Rijk van Dijk, page 283)

ANTI-RETROVIRAL TREATMENT: FAILURES AND RESPONSES

Leprosy of a Deadlier Kind: Christian Conceptions of AIDS in the South African Lowveld (Isak Niehaus, page 309)

Subjects of Counselling: Religion, HIV/AIDS and the Management of Everyday Life in South Africa (Marian Burchardt, page 333)

Therapeutic Evangelism-Confessional Technologies, Antiretrovirals and Biospiritual Transformation in the Fight against AIDS in West Africa (Vinh-Kim Nguyen, page 359)

Conclusion (John Lonsdale, page 379)

Notes on Contributors (page 385)

Index (page 389)

Citation preview

Aids and Religious Practice in Africa

Studies of Religion in Africa Supplements to the Journal of Religion in Africa

Edited by

Paul Gifford School of Oriental and African Studies, London

VOLUME 36

Aids and Religious Practice in Africa Edited by

Felicitas Becker and P. Wenzel Geissler

S ‘ 46

BRILL LEIDEN « BOSTON 2009

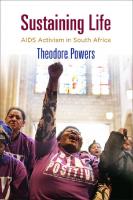

Cover illustration: Young woman praying during a Legio Maria healing ritual, western Kenya. Photograph by Wenzel Geissler, 2001.

This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data AIDS and religious practice in Africa / edited by Felicitas Becker and Wenzel Geissler.

p. ; cm. — (Studies of religion in Africa, ISSN 0169-9814 ; 36) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16400-0 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. AIDS (Disease)—Africa— Religious aspects. I. Becker, Felicitas, 1971- I. Geissler, Wenzel. III. ‘Vitle. IV. Series: Studies on religion in Africa ; 36. [DNLM: 1. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome—Africa. 2. Religion and Medicine—Africa. WC 503.7 A2868 2009] RA643.86.A35A343 2009 362.196°97920096—de22 2008049236

ISSN 0169-9814 ISBN 978 90 04 16400 0 Copyright 2009 by Koninkliyke Brill NV, Leiden, ‘Uhe Netherlands. Koninklyke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Koninklyke Brill NV has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklyke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS

CONTENTS Introduction: Searching for Pathways in a Landscape of Death: Religion and AIDS in Africa wo eecececceceeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeees | Felicitas Becker G PR Wenzel Geissler

NEW DEPARTURES IN CHRISTIAN CONGREGATIONS OF LONG STANDING The Rise of Occult Powers, AIDS and the Roman Catholic Church in Western Uganda 0... eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeteeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee = 29 Heike Behrend

Christian Salvation and Luo ‘Tradition: Arguments of Faith

ina lime of Death in Western Kenya... eee 49

Ruth Prince

The New Wives of Christ: Paradoxes and Potentials in the

Remaking of Widow Lives in Uganda ou... eee 85 Catrine Christiansen

CONVERGENCES AND CONTRASTS IN MUSLIMS’ RESPONSES AIDS and the Power of God: Narratives of Decline and Coping Strategies 1n Zanzibar .o..eeeeeeeeeeeessssttttteteteeeereeee = LILY Nadine Beckmann

Competing Explanations and ‘Treatment Choices: Muslims, AIDS and ARVs in ‘Tanzania oo eesessssseeeeetettteetertrterreeee, = LOD felicitas Becker

‘Muslims Have Instructions’: HIV/AIDS, Modernity and

Islamic Religious Education in Kisumu, Kenya .......... 189 Jonas Svensson

v1 CONTENTS PENTECOSTAL CONGREGATIONS BETWEEN FAITH HEALING AND CONDEMNATION ‘Keeping Up Appearances’: Sex and Religion amongst University Students in Uganda wocssccccccceceeteeeeeeeeeeeeeee 223 Jo Sadgrove

Healing the Wounds of Modernity: Salvation, Community and Care in a Neo-Pentecostal Church in Dar Es Salaam, TanZania oieeeesssssssssccccecccccceccceccccccceeecceeeeeeeeeeeeeeceesesseesetseeestsses DOO

Hansjorg Dilger

Gloves in ‘Times of AIDS: Pentecostalism, Hair and Social Distancing in Botswana .........eeeeeeeeesssseeenreeeeeeeeeeeeeesstsststsstteteee, 209

Ryk van Dyk

ANTI-RETROVIRAL ‘TREATMENT: FAILURES AND RESPONSES

Leprosy of a Deadlier Kind: Christian Conceptions of AIDS in the South African Lowveld oe... eecceeeeeeeeeeeesssssstetteeeee, OO Isak Niehaus

Subjects of Counselling: Religion, HIV/AIDS and the

Management of Everyday Life in South Africa we. = 333 Manan Burchardt

Therapeutic Evangelism—Confessional ‘Technologies, Antiretrovirals and Biospiritual ‘Transformation in the Fight against AIDS in West Africa... eeeeeceeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeseeeee DOO Vinh-kim Neuyen CONCLUSION vee eeeeeeeeessssssneeeeeeeeeeeecesesssssssssstteesessssssssssssseee I/O

John Lonsdale Notes On Contributors oo. ecccccccccececeeeeceeeeeeeeeeeesesesssetsteesteeses DOO Index eee eeeesesssneceeeeeeeesssseeeeeeeecessssssaeeeeessessssssseeeesessssssseees OOD

INTRODUCTION: SEARCHING FOR PATHWAYS IN A LANDSCAPE OF DEATH: RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA Felicitas Becker & P. Wenzel Geissler AIDS, Africa and ‘religion’

Nobody would deny that religious practice 1s important in confronting AIDS in Africa, but the attention given to religion in the context of the AIDS crisis has maintained a fairly narrow focus. The role of religious organisations in providing care and support for sufferers is well known (e.g., Islamic Medical Association of Uganda 1998; Benn 2000).

It has recently been boosted by the channelling of much of the USA‘s government’s substantial funding for HIV/AIDS treatment and care through ‘Faith-Based Organizations’ (BOs), and these organisations, in turn, have multiplied and expanded their work. Religious groupings are thus instrumental in, instrumentalised by, and arguably instrumentalising the organisation of HIV-related interventions. It is also well known that on other occasions, religious dogma has proved antithetical to the struggle against the epidemic, for example in the cases of some forms of evangelical fundamentalism and the official line of the Catholic Church regarding condoms to prevent HIV infection. Both these aspects—the role of religious institutions in care, and of religious ideas in negotiating appropriate preventative measures—will also be addressed in this volume. The focus of this book, though, lies elsewhere: on the way people rely on shared religious practice and notions and on personal religious commitments in order to conceptualise, understand and thereby to act upon the epidemic, and on the suffering and loss that it brings about, so as to pursue life and creativity

in spite of it. he aim is not to supplant, but to add to the alreadyexplored perspectives. In particular, tracing the involvement of religious practices and commitments in dealing with AIDS helps understand (and hopefully constructively address) those religious reactions that at first appear unhelpful to experts focusing on treatment and prevention. ‘The studies presented here encompass East and Southern Africa as well as one West African case, with a bias towards East Africa. ‘lo some extent, this bias reflects the research orientation, and hence networks,

2 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

of the editors (rather than any preference on their part). But it also reflects the fact that research on the ramifications of the AIDS crisis has been going on for longer where this crisis 1s older and most acute. Given Africa’s diversity, even continental coverage would never have been achievable, and it is to be hoped that West Africa does not have to suffer an AIDS crisis of the same proportions as the South or the East of the continent to encourage interest in the issue. In the following pages, we discuss some of the issues that connect the otherwise diverse contributions. We aim to highlight some reasons why the interaction between AIDS and religious practice 1s important, and to point out directions for further research. Firstly, though, we have to clear the ground a bit by explaining our use of the notion of religion and its aspects, religious practice, thought and commitment. ‘That done, we examine an apparent turn towards restrictive application of religious dogma that connects religious debates about AIDS with broader trends of religious change. Next, we discuss the interaction of religion and AIDS in the context of Africa’s ever-deferred hopes for progress and modernity. ‘This leads on to questioning the part of politics in this interaction. Lastly, we give space to the implications of the ongoing ‘roll-out’ of anti-retroviral drugs: not only because it changes many of the equations discussed here, inasmuch as they were observed before wider access to antiretroviral medication, but also because it suggests new directions for research. Refractions of the notion ‘religion’

Given the increasing salience of religion as a motive, or pretext, for action (as well as the refusal to act) in global public discourse, and the closeness of HIV/AIDS to suffering and death (phenomena which are readily defined as a preserve of religious specialists even in the most secularised societies) the importance of religion appears obvious. But what sort of religion? The authors assembled in this volume are not interested primarily in the role of professional religious experts, and do not limit themselves to organised religious practice. ‘hus although the contributions focus on groups that either explicitly or indirectly draw

on the teachings of either Islam or Christianity, they set out from a notion of religious commitment and practice as part of everyday life. As such faith is inevitably informed by the intellectual-cum-social-cumpolitical currents mixing in Africa today: local religious heritages, world

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 3 religions, notions of science and progress, the biomedical discourse of

AIDS campaigns and the authority of the state that endorses them, and, not least, the experience of material deprivation which the destructuring and criminalisation of African nations and economies have brought about (see, e.g., Gifford 1994; Maxwell 1998; Meyer 1999; Sanders 2001). ‘The interaction between religion and AIDS, in other words, 1s bound up with the wider experience of suffering within which the epidemic is set, and with other non-religious narratives and practices through which people address the experience of HIV/AIDS. On such ‘popular epidemiologies’ there is by now an important body of literature (see Setel 1999: 183). It tells us that people and communities affected by the virus range far and wide in their search for explanations, calling upon their knowledge of politics, commerce and international relations as well as diverse views of health and healing. In these public searches for meaning, AIDS can as well become a divine punishment, as it can turn into witchcraft (e.g, Yamba 1997), or into biological warfare or a plot hatched by authoritarian governments, single super powers and international donors (e.g., Schoepf 1995; Hooper 1999; Pickle et al. 2002; for an overview, see Iliffe 2006: 80). ‘These insights have provided many leads for the contributions to this volume. Nevertheless, the studies presented below indicate that it would be misleading to subsume the diversity of such non-scientific explanatory narratives as now abound in Africa under a vastly broadened concept of ‘religion’. For instance, Ells & ‘ler Haar have recently categorised discourses about anything invisible as ‘religious’, and ascribed to African cultures a propensity to focus explanations for calamities as well as for power and success on such invisible forces (2004). ‘Their account refocuses attention on the salience of notions of the occult in Africa’s politics and on the relevance of religious practice to addressing social anomie. Still, subsuming the doubts and speculations that haunt African public debates and politics under an extended notion of ‘religion’ risks

reiterating old debates about the ‘rationality’ of African actors and evoking dated cultural stereotypes. With regard to the subject in this collection, the result would be to lump together all narratives outside the narrowly defined scientific truth about AIDS as ‘religion’. ‘This, in turn, would provoke the question why faith in sclence—which after all is equally invisible to all but few people—should not be classified as religion, too. In effect, 1t would give simultaneously too little importance

4 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER and too much meaning to economic anxiety and political rumours, and misrepresent the religious.

The present collection suggests that religious commitments and practices, In contrast to urban myths, political rumours and trust in scientific authority, are not primarily about ‘the invisible’. Rather, they are about the everyday, tangible, material world and its inherent forces, about the humans and things that make up one’s world and constitute life, and about the relationship between this realm and that of divinity.

It is to these forces and this relationship, within, rather than outside, everyday life, that many of the contributors to this volume attend: to the ways in which people in Africa navigate a way through landscapes which some of them describe as ‘dying’, but which nevertheless are the only ones available to them, and the ones that sustain their lives and hopes. The variety of phenomena discussed here highlights not only the absence of a comprehensive definition of ‘religion’, but also the problematic nature of this concept in African contexts. Paul Landau (1999) has argued that the notion of ‘African ‘Traditional Religion’ in itself 1s intricately connected to missionaries’ efforts to identify and manipulate what they had made out to be their indigenous ‘competition’, and that the appropriation of Christian concepts in Africa has long born traces of the initial relationship between Christian masters and ‘pagan’ servants. In the present context, it 1s typically Africans who evoke notions of religion, its deficiencies or absence, to make points about health and society. Still, 1t 1s well to keep in mind that the religions people argue

about or appeal to are something negotiated and constructed among unequal relationships, rather than found in place. It helps understand the implicitly political nature of the Muslim reformists discussed by Becker, Beckmann and Svensson, as well as the South African Zionists and Pentecostals observed by Niehaus and Burchardt. Prince’s argument about the co-construction of born again Protestantism and neo‘Traditionalism in Kenya has a similar thrust. Religious arguments, in this context, make reference not only to the spiritual, but, as anthropologists

have shown many times over, to history and the political-economic process (e.g. Gomaroff & Comaroff 1991). In fact, AIDS prevention efforts suggest other long-term continuities

than those traced by Landau, between the activities of missionaries and those of AIDS experts. Much as missionaries defined (African) ‘religion’ as either aligned with or opposed to their ultimate aim of saving souls, contemporary AIDS institutions engage with (and thereby

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 5 define) ‘religion’ as an order of meaning and of social relations, which can either facilitate or obstruct their efforts to change ideas and practices and save lives. This continuity 1s evident also in the way AIDS education focuses on and problematises women. Similar to the missionaries’ concerns (later taken up by colonial government) with ‘hberating’ African women by improving their hygiene and childcare skills and recreating them as modern, Christian wives (see e.g. Vaughan 1992; Hunt 1999; Ferguson 1999, Mutongi 2007), today, again, women’s behaviour is seen as crucial to stemming the tide of AIDS. ‘This time, women are expected to learn a version of late-Huropean-modern female assertiveness in gender relations (if often in a Christian guise), rather than the housewifeliness

of mission modernity. he papers presented here give some insights into why such ‘life skills’ in gender relations and sexual practice are often hard to apply. Besides the well-known facts of economic and personal dependency, there are things at stake in which women may be particularly invested or which affect them more: for example, broader

Luo understandings of growth (Prince) or Muslim notions of female virtue (Beckmann, Svensson). At the same time, as Christiansen’s chapter shows, some women actively embrace religious forms to remodel their

womanhood in the days of AIDS. Despite these doubts about the value of ‘religion’ as analytical category, and especially so in the African context, we have retained the term, if used sparingly, due to its organising capacity. Irrespective of our difficulties in coming a lasting and transferable definition of religion, many people in Africa (as elsewhere) attribute great importance to that which it is used to describe and may apply it to core concerns in their lives. It is ultimately due to the evocative quality of the term as well as its sheer convenience, rather than the analytical usefulness of the concept, that we can use religion as a useful way to approach understandings of and ways of confronting AIDS. AIDS and the prescriptwe turn in religious life

In medical and policy debates about HIV/AIDS, the place of religion is sometimes deceptively clear: the preserve of religious experts is to preach and oversee behavioural change, if not only for biomedical reasons. Religious commitments, in this view, are above all a source of restrictions, and ideally a force to restore order in the face of (primarily

6 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER sexual and gendered) confusion. Yet, whether religious restrictions of personal freedom will actually reduce the risk of acquiring AIDS is an open question. With many other studies, several contributions to this volume underline that the famous ABC (‘Abstinence, Be faithful, use a Condom) formula for HIV prevention, with its emphasis on ‘choices’, barely scrapes the surface of the way people experience, practise and

think about sex. Risky behaviour can arise from lack of choice and imbalanced power relations, but also from the fact that the concept of viral infection may be alien, or less important than ritual obligations to engage in bodily intercourse. People may give religiously sanctioned relations precedence over concerns with the individual body and life-

expectancy, and prioritise the wish to have children and be part of a larger process of life. Religiously motivated self-restraint 1s one factor among many social commitments operative here.

Religious rules can even be a risk factor in the context of AIDS. The official line of Catholic Church is to condemn the use of condoms, still the only effective way of avoiding infection outside exclusive

relationships with an HIV-negative partner. Likewise, the evangelical Protestant lobby that has recently shaped much American AIDS policy rejects condoms as well as extra-marital sexual intercourse. It has succeeded in tying the recent ‘Presidential’ funds for antiretroviral drugs, a substantial contribution, in material terms, to global health intervention and the fight against AIDS, to the condition that abstinence and faithfulness, rather than condoms, are advocated for HIV prevention, and to a preferential use of BOs for HIV-prevention efforts. At the

inter-personal level, different studies of gender, HIV and religion have shown that born-again Christianity can ‘empower’ women to protect themselves against unwanted sex and HIV infection (Cattell 1992; Ogden 1996; see also the chapters by Christiansen and Prince), although it has also been suggested that Pentecostalism might subdue women under renewed patriarchal control and thereby expose them to unwanted and unprotected sex (Mate 2002). It is no coincidence that many of the chapters examine new, radical religious movements. Pentecostalism, Revivalism, neo-lraditionalism and Muslim reformism are all characterised by their demand for exclusive commitment and for a fundamentally restructured everyday life, often focusing on mundane practices. They present different instances of the growing importance of religious prescriptions in contemporary Africa as much as many other parts of the world. The intensification of the restrictiveness, even aggressiveness, of religious injunctions that

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 7 the present contributions suggest (Becker, Behrend, van Dik, Prince, Svensson) presents an explanatory problem. In spite of initial appearances, the causal relationship between it and the experience of AIDS is not obvious. Has the trauma of AIDS-related suffering triggered a tightening of religious restrictions, as part of avoidance strategies that can border on panic, or have religious groups already committed to the tightening of dogmatic stances been able to seize the metaphor of AIDS to promote their interpretation of religious morality and practice, as well as the influence of their organisations? ‘The stress, fear and misery associated with AIDS provide an obvious reason for the further enforcement of restrictive ‘avoidance strategies’.

It is fair to assume that the AIDS-induced sense of crisis and rupture in both individual lives and the fabric of sociality encourages exclusionary actions, as among the Catholic witch-hunters observed by Behrend, stark personal choices, as among Christiansen’s young Saved widows, and restrictive interpretations of religious practice, as among Becker’s reformist Muslims and Prince’s traditionalists. Yet, such processes of

exclusion are likely to be ambiguous as the passage from rhetorical commitment to everyday practice is more complex than explicit statements of it generally allow. The tensions between Pentecostal commitment, personal practices and social commitments are well illustrated by Sadgrove’s chapter on Ugandan university students, and van Diyk’s on Ghanaian Pentecostal hairdressers; while the former, despite strong religious commitment, do not always follow their prescriptions, the latter emphasise religiously motivated separations overlapping with class difference, and draw selectively upon the religious obligation to care for others. The overall increasing rigidity of religious notions, or assertiveness of their proponents, invites speculation on the ‘revenge of God’ (see Kepel 1993), not on Africa, but on the relativist anthropologist. ‘The global rise of religious fundamentalisms in all three monotheist religions—and, partly in response, in ‘traditional’ religion—has baffled western observers who took the restriction of religious commitment to a personal and private sphere as part and parcel of the inevitable diffusion of modernity, in Africa as elsewhere. Instead, the evidence increasingly supports the assertion that rigid distinctions between believers and unbelievers, the saved and the rest, are a characteristic aspect of what Latour described as the ‘modern constitution’ (1993).

In Africa, these radical dichotomous patterns were promoted, in particular, by Christianity. While the early expansion of Islam in Africa

8 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER initially produced relatively open forms of Islamic practice, Christian influences introduced with colonial mission have since their inception considered their project as one of opposition and struggle—against pagan tradition, immorality and the past—and they have introduced Manichaean morality and according behavioural prescriptions, enforced by racial and economic segregation, into the African religious imagination. It 1s thus clear that exclusivity and restrictiveness, prescriptions and prohibitions, have been observable well before AIDS, and arguably even before the recent rise of rigid, prescriptive religious discourses. While restrictiveness clearly is an important characteristic of faithbased responses to AIDS, it need not be overemphasised to the expense of other dimensions of religious experience. Some earlier anthropological studies of AIDS in Africa drew heavily upon academic concepts like ‘taboo’ to argue that indigenous religious explanations attributed AIDS-related death to rule-infringements (see for an overview Iliffe 2006: 91-92). But besides prohibitions and separations operate the unifying and merging dimensions of religious commitment and practice;

the double bond that religious experience and practice has with both order and disorder. As Victor ‘Turner, among others, has shown, religious commitment and engagement with divinity involves both rules of restraint and separation, e.g. abstinence in customary ritual or Christian and Muslim conduct, and commitment to the opposite, communitas and

transgression of boundaries. ‘his may be reflected in rituals of communion such as the emphasis on prayer among reformist Muslims that feature in Becker and Svensson’s accounts or the liturgical practices of charismatic churches like Sadgrove’s and Dilger’s Pentecostals. It also occurs in the liminal states that are involved in possession by the Holy Ghost (Dilger, Sadgrove, Behrend) or ancestral spirits (Prince), or in prescribed ritual (or marital) sexual intercourse, as the rituals of widow inheritance, discussed by Christiansen and Prince, illustrate. Rather than providing prescriptions and distinctions, religious practices—initiation rites as much as the Christian Eucharist or Muslim Salat—also potentially imply the creative dissolution of boundaries and the transformative merging of ordered separations, from which life-force is released. ‘Vhus understood, religion allows the possibility of

uncertainty and surprising event, rather than erasing doubts; it opens up pathways rather than setting closed frames, ‘starting points and not finalities’, in the terms of Susan Whyte’s pragmatist anthropology (1997: 20). Most of the papers below show that religious debates in

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 9 contemporary African everyday life do not succeed in imposing a closed dogmatic order or fixed explanatory frames, despite concerted efforts by some to deploy religion to such effect. Instead, religious knowledge and practices open up fora to negotiate the relations between creative order and amorphousness, between collective rules and particular desires, and

between life and death. While the struggles of East African widows between Christian and ‘traditional’ religious and other commitments show this tension most clearly, similar tensions are at play between traditional and reformist Muslims in Becker’s chapter. AIDS, religious change, and the long-term slide towards Africa’s ‘abjection’

The focus on AIDS as central event and narrative which is characteristic of much literature on the epidemic does not necessarily reflect Africans’ experience. What biomedically appears to be AIDS 1s usually discussed in relation to wider social ills rather than to an immunological imaginary, and these critical discussions insert themselves into narra-

tives about destruction, confusion and loss, which have been told in eastern Africa since the early years of the last century (see, e.g, Cohen & Odhiambo 1989). ‘This longer historical trajectory is what lends force and credibility to the South African president ‘Thabo Mbeki’s seemingly

irrational argument concerning the origins of HIV beyond the narrow confines of virology (see Fassin 2007). Epidemics, of rinderpest and sleeping sickness, measles and influenza, have featured in these narratives, as have ‘outbreaks’ of religious fervour—sometimes one related to the other (e.g., Ogot 1963: 255-7; Ranger 1992a). What Prince’s Kenyans call ‘the death of today’—the AIDS-related sickness and death of the past decade—1s widely regarded

as but the most recent consequence of longer processes of change that have affected the constitution of sociality itself. ‘The nostalgia and laments about loss and anomie that dominate in the views of Niehaus’s rural South African informants, as well as in contemporary Zanzibar and western Kenyan public oratory, are a recurrent theme in twentiethcentury Africa (see, e.g., Prince 2006; Ferguson 1999). ‘The words of Achebe/Yeats, ‘things fall apart’, which generations of East Africans have read in school, make as much sense (though possibly referring to different ‘things’) to young people today as they did to their grandfathers. This contrasts with the presentism of research funders, public health experts, policymakers and the mass media, who may ignore the fact

10 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

that AIDS is but one of the scourges that have befallen Africa over the past century. Nevertheless, AIDS 1s a scourge that could be said to strike at the very core of religious practice. Anthropologists have observed the ‘sacred’ status of bodily intercourse and gendered relations of humans as well as non-human entities (e.g. Heald 1999; Sanders 2002) in Africa. Others

have noted religious concern with generation (e.g. Lienhard 1961; Turner 1967) in many African societies. While it would be reductionist to associate African religious practice with ‘fertility’, narrowly focusing on biological understandings of reproduction, most scholars would agree

that acts of gendered complementation, and of creative unions have a particular place in non-Christian (and, arguably, also Christian and Muslim) forms of religious imagination and practice in Africa. Already the destructive dimensions of colonial occupation and of economic exploitation and neglect, which produced profound changes in kinship and livelihood and challenged older notions of ‘growth’, therefore went to the heart of religious commitment. Bans on polygamy and widow inheritance, restrictions on sexuality and fertility, as well as loss of

land and livelihood and shrinking cattle and pasture, malnutrition and new infections, all challenged prevailing ways of engendering human growth through ritual practices. After all this, it 1s little surprising if AIDS, conceived of as final cessation of growth after the bodily union turned into a source of death rather than renewal, appears to complete secular processes that have eroded both African modes of living and engendering life, and the attendant religious or ritual forms. While AIDS is not perceived as a radically new experience, neither are the religious engagements with AIDS. The experience of this illness is embedded both with much older debates among Africans on the ways their lives have been changing, and with the experience of these changes themselves. ‘These changes have often been forceful and destructive, and ambiguous even during the short period of the colonial and post-colonial ‘the developmental state’ between the 1940s and 80s; during the past two decades of neoliberalisation and economic and political crisis—that 1s in most living people’s memory—they have been overwhelmingly negative. ‘The encounter between religious practice and AIDS, then, is part of Africans’ long-standing struggle with adversity, assault and domination. ‘Thus, both the turn towards faith healing, with its processual, euphoric

and trance-like qualities, and the re-examination of behavioural rules and scriptural teachings in the context of AIDS draw on long-standing

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA I] notions and practices. Prophecy and possession have been involved in confronting colonial rule and in living with it, inspiring movements such as langanyika’s Maji Maji, Kenyan Mumbo or Central Africa’s Watchtower (Iliffe 1979; Wipper 1978; Fields 1985). Spirit possession has provided spaces of action for Muslim women in Africa probably for centuries (Boddy 1989; Makris 1996). Clashes between religiously founded rules of differing derivations pre-date colonialism in the case of Islam; they have been a salient feature of mission Christianity for the whole of its existence (Pels 1999). AIDS, science, and deferred modernity

Coping with AIDS, then, is but the most recent in a long line of struggles that people in Africa have lived through in the second half of the twentieth century. The foreclosure of ways for individuals and communities to grow—in terms of kinship and personal advancement—already motivated resistance to colonial rule, and it has recurred in a multitude of guises since (Lonsdale). Economic turnarounds beyond

the control of Africans, and equally uncontrollable, if more locally produced, political uncertainty, have translated into accumulating strictures and hardship. Africa has experienced a long, slow decline from the optimism of the mid-twentieth century age of ‘development’, and its people are struggling to make sense of this predicament—Africa’s current ‘abjection’ (Ferguson 1999)—which seems to aflect everything,

from individual bodies and lives to the wider social, economic and political world.

The papers in this volume again and again show that to the minds of many people living through it, the AIDS epidemic 1s not a clearly delineated specific event, but a part or a stage in a long procession of misfortunes. ‘hus they also suggest that it is part of the attraction of faith-based explanations of HIV/AIDS that they resemble the problems Africans face in being wide-ranging and comprehensive. ‘They do not promise only to help people deal with AIDS, but offer explanations also of other social ills, and suggest entire ways of life. Religious debates in the times of AIDS therefore also contain a critical evaluation of the past century of change, and they are always discussions about the ‘problem of modernity’ and its instantiations, such as the state and its laws, capitalism and economic differentiation, and science and medicine.

12 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

Regarding the relevance of the notion of modernity for people in Africa, the papers highlight the extent to which it has become an ‘emic’ term; part of the way people in Africa think about their predicament. For example, Pentecostals in Dar es Salaam (Dilger) as well as Muslims in Mainland ‘Tanzania and Zanzibar (Becker, Beckmann) all grapple with the notion in different ways. Clearly, the meanings of modernity are slippery and its evaluation is ambiguous; it may be an unfulfilled promise (Becker) or an accomplished process of alienation (Beckmann).

One way of acknowledging this diversity 1s by including everything contemporaneous with the present into the purview of ‘modernity’. ‘This makes witch burnings and criminal states into ‘African modernities’ (e.g. Comaroff & Comaroff 1993). James Ferguson, however, has warned that this inflationary use of modernity may be politically counterproductive, contribute to the dissolution of the modern project, and that it is likely to be incomprehensible, indeed offensive, to African citizens for whom ‘modernity’ has quite clear meanings such as effective health care, democratic representation and employment (2006; see also Deutsch et al. 2002). ‘The contributors to this volume on the whole treat ‘the modern’ as possessing a more specific meaning than that captured by ‘multiple modernities’, yet slightly broader than these material hopes and aspirations. Here, modernity refers to a historically situated project, which alongside the progress implied by ‘modernisation’ also refers to a particular governmental order and particular forms of discipline and morality (see Ferguson 1999, Becker 2008, Prince & Geissler 2009). It is the crisis of this ambiguous project that interacts in several of the chapters below with religion and AIDS. Understood in this way, ‘modernity’ is something that the African religious actors discussed here situate themselves towards in different ways. Ghanaian Pentecostals in Gaborone (van Dik) and Ugandan ones in Kampala (Sadgrove) appear to view modernity as something they still have to bring about by their actions, while the Pentecostal community in Dar es Salaam observed by Dilger is seeking, in his words, to heal the wounds modernity has caused. Meanwhile the members

of rural African-led churches in South Africa observed by Niehaus might agree with Zanzibari Muslims encountered by Beckmann that modernity has washed over them and left them to pick up the pieces. Muslim teachers in Western Kenya (Svensson) and Muslim radicals in ‘Tanzania (Becker), meanwhile, look upon the means to be modern as something to be wrested from Christian ideology and state control.

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 13 Prince, by contrast, describes ‘neo-traditionalists’ using an idiom of wholesome tradition and contemporary (modern) corruption, which reflects older idioms of distinction and rupture, such as missionaries’ invective against pagan ‘backsliding’.

On the whole, the present contributions reinforce a point that has recently passed from being controversial to forming a new consensus: the fundamental(ist) elements in the religious discourses examined here

should be understood, not as pre-modern atavisms or anti-modern reactlon—naive attempts to reconstruct past epistemologies and social orders—but as characteristically modern forms of argument, situated in modern experiences and even if not necessarily about modernity, still firmly rooted within it (see e.g. Eickelman and Piscatori 1996; Englund & Leach 2000). At the same time, these arguments can be said to reflect a broader modern tendency to classify and separate (Latour, 1993). But recognition of their falling into this widespread pattern 1s no substitute for tracing the more specific motives that animate, for instance, the antiwitchcraft “carpet bombers’ Behrend describes, or the Muslim reformists and Luo traditionalists that Svensson and Prince, respectively, observe in the same area of western Kenya. Medical science is a particularly important refraction of the modern experience in the current context. In biomedical recommendations and education programmes focused on them, African AIDS victims encoun-

ter the entire complex of the practice of science and of ‘scientism’ (the evocation and reification of science for specific goals). People in Atrica have long been told that ‘scientific’ attitudes are a precondition for ‘development’. Now, medical experts’ insistence that they have no cure for AIDS, intended as a warning against risky behaviour and bogus cures, 1s easily taken as a declaration of the defeat of science. African listeners may take scientists’ insistence on their own limits as their giving up on addressing the continent’s problems, all the more as in Africa’s

post-colonial experience, the blessings of development and science have been permanently unequally distributed and often elusive. Such interpretation is expressed in the rumours, widespread in Africa, that ‘the Americans’ or ‘the Whites’ have a cure for AIDS which they refuse to share with African sufferers. ‘These rumours, in turn, hark back both to Biblical idioms of ‘stolen blessings’, and to political calls for access to free antiretroviral treatment and care.

‘The widespread occurrence of faith healing, especially among Pentecostals, is clearly an attempt to provide possibilities where scientists and medical doctors appear to fail. ‘he conflict between Christian

14 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

healing and biomedicine, moreover, reveals to Africans a split within the ‘Western tradition’, as both the lines of thought, both Christianity and modernist scientism, have European ancestry and were closely

intertwined in their colonial origins (see e.g. Ranger 1992b). One might surmise that the present shift, across Africa, from the old mission Churches to new forms of Charismatic and healing ministry, is related to this loss of credibility of the older alliance between biomedicine and ‘mainstream’ denominations. But, as Dilger’s paper describes, believ-

ers in faith healing are also finding compromises that allow them to combine the solace of faith healing with an acceptance of biomedical interpretations. A similar point can be made about Muslim reformists. However rigid the prescriptions for their co-religionists’ behaviour that

they propose, their insistence on the centrality of the scriptures for Muslims and on formalised ways of interpreting them 1s also an assertion of a different kind of rationality. ‘hey often insist that the Qur’an does not clash with science, but rather endorses and prefigures it. At the same time, they proudly assert the moral as well as technical relevance of the Qur’an, which, to their minds, 1s a particular strength of Qur’anic as opposed to scientific rationality. ‘The restrictive rhetoric of Muslim reformists notwithstanding, more mainstream Muslims, too, struggle to reconcile the findings of science with the scriptures. Much like Christians, they find ways to live with the disaster unfolding around them by placing it within God’s plans. Thinking and acting about AIDS, then, people in Africa also reassess the elusive promises of modernity and its harbinger, science. At times, it appears that, having found themselves excluded from the once so promising ‘modern world’, they are finding entirely new categories to define their place in the world. Pentecostal Christians are defining this transient world ever more starkly in contrast to the next, eternal one, hoping for a leap forward in time. Muslims, on the other hand, insist on the necessity for their home regions to become fully integrated into the Dar-ul-Islam, the realm of Islam, which they oppose in spatial, rather than temporal, terms to ‘the West’. ‘[raditionalists advocating ‘African custom’, meanwhile, are developing an account of their home regions as culturally separate from other regions of the world and threatened in their authenticity; where Pentecostal Christians propose a rupture forward and away from the world, traditionalism could be said to call for the opposite move, back to the origins, and to the earth.

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 15 AIDS, religious congregations, and politics

A political strand runs through the narratives in this collection, of secular decline and attempts to situate oneself towards modernity. It 1s most obvious where the actions of the state are at stake, but typically it does not stop there, and often it is more submerged. It has been said that in societies where descent networks are crucial for organising social interaction, cooperation and control, ‘public’ and ‘private’ domains become intermingled (Marks and Rathbone 1983; see also Giblin 1992).

The presence of the state notwithstanding, the web of relationships constituted by families, kin, and religious congregations still shapes a person’s options for autonomy and dependency, and personal well-being

remains intertwined not only with that of religious congregations but also of the body politic.

The failures and limitations of official capacities to counter the AIDS epidemic leave a space for religious action to occupy: the relative dearth of counselling services in Cape ‘Town (Burchard) and of medical and social services at large in Dar es Salaam (Dilger) frame religious responses to AIDS. Religious congregations and I’BOs thereby end up paralleling state institutions. ‘The relationship is not only one of marginalisation and mutual avoidance, though: Muslim secondary school teachers in Western Kenya, for instance, use their curricula on AIDS

with a sense of official entitlement, as Svensson shows. At the same time, the relationship between FBOs and the congregations in which they are based has its own political problematic. Nguyen’s study of counselling organisations in Burkina Faso, which in effect serve as a gate-

way between HIV-positive patients and ARV providers, indicates this.

The conjuncture of concern about AIDS, societal—particularly moral—decline and the failures of the state is clearest in two otherwise very different settings: among rural Zionist Christians in South Africa (Niehaus) and urban Muslims in Zanzibar (Beckmann). ‘The former experience post-apartheid South Africa as a site of continuing, even increasing social anomie, where the state continues to be part of the problem rather than the solution. ‘The latter translate concern about

Zanzibar’s marginality within the Tanzanian state into a discourse

of Islamic morality under threat. However, in spite of the much more proactive response to HIV/AIDS of the Ugandan government, Behrend here found Catholic witch hunters who act on a perceived need to tackle the rise of occult forces: in this case, the aggressive and bitter response cannot easily be explained with official neglect or

16 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER meddling. ‘The perceived failures always take place at the local as well as the national level. ‘he people observed by Niehaus and Beckmann

in fact recognise this, as their debates oscillate between political and communal failures.

Still, even in countries with ‘weak’ states, the health of citizens remains intertwined with that of the political system. Becker suggests

that the relations of religious experts to the state shape both their response to state-endorsed AIDS education, and their listeners’ response to the advice they give. Prince’s discussion of customary practices and inheritance law points at the fraught relationship between different legal

frames and the absence of democratic public negotiations of these; moreover, the adjudication of a “Luo council of elders’ draws attention to the lack of democratically constituted legal bodies and a civil society engaging with these. Behrend’s ‘carpet bombing’ Catholic vigilantes are likely to be informed by Uganda’s warlike recent history. ‘Uhus, even with an issue as personal as how to live with the danger and suffering of AIDS, religious commitment does not escape the realm of politics. It is clear that, for Muslims, AIDS is implicated in an uneasy negotiation of their position within the East African states. Yet for Christian denominations, too, the way they place themselves vis-a-vis the state needs constant watching and re-thinking (Gifford 1994). At a more intimate level of power relations, Prince and Christiansen present strikingly different trajectories and interpretations in neighbour-

ing regions on the northern shores of Lake Victoria: Prince among Kenyan Luo, Christiansen among Luhya people in across the border in Uganda. In both cases, villagers are concerned about the continuance

of widow ‘inheritance’ in the presence of AIDS; about negotiating ‘Saved’ Christian condemnation of the practice, and about alternative means of ensuring the continuity of life. Yet while Prince focuses on collective efforts to maintain ’growth’ through relations with the past, and personal compromises inspired by these efforts, Christiansen emphasises widows’ readiness to break away from preconceived social roles by evoking ‘saved’ status. ‘The contrast 1s only partly a matter of diverging research interests. It also shows how similar religious injunctions can impinge very differently on individual lives. ‘The differences are the outcome of contingent societal factors among which legal and

economic factors are prominent: the politics of the family are not ultimately isolated from formal politics.

The authors gathered here, then, present both contrasts and continuities with other recent publications on AIDS that have examined the

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 17 politics, or apparent lack of it, of the African AIDS epidemic. Alex de Waal, for example, has deplored what he perceives as the political quiescence surrounding AIDS in Africa, and attributed it above all to denial, both among politicians and populations (de Waal 2007). ‘The accounts presented here suggest something quite different from political quiescence and denial: widespread, diverse efforts to respond, both practical and intellectual, but predominantly directed towards realms of social action which escape de Waal’s narrow, state-centred definition of politics. By contrast, Epstein’s focus on the importance of behavioural change in slowing down Uganda’s epidemic, and the role of internal politics in international AIDS organisations in obscuring this factor, resonates with the emphasis on intimate negotiations and problematic relationships with officialdom in the present collection (Epstein 2007). Iliffe, too, (2006: 126-131) interpreted the evidence on behaviour change in Uganda to mean that people reduce risky behaviour once the theses of AIDS educators have been borne out by people’s own experience. Once enough people have died for conclusions to be drawn about the patterns in these deaths, the desire to live, he suggested, would lead

to the appropriate pragmatic responses. [The present collection of case studies similarly shows that people are learning quickly; that they are looking for the causes of the epidemic and for ways to control it, and that, despite the mistrust towards officialdom, biomedically based explanations and recommendations are seriously discussed along with others. ‘hese learning processes can in turn impact on ritual practice, as the discussions, in Kenya and Uganda, about less risky alternatives to the neo-traditional prescriptions of ‘widow inheritance’ show (Prince and Christiansen). Yet, to arrive at such reforms of knowledge and practice, politics and policy must work towards certain basic conditions. In particular, people must be able to access, negotiate and weigh information from different sources so as to try out different interpretations. ‘hey must,

for example, develop a workable notion of sexual transmission and they must be in a situation in life that allows them weigh the avoidance of risk against other considerations, whether ritual, romantic, pragmatic or mercenary that may encourage risk-taking. They also need access to the material tools of preventing and countering HIV infections: condoms and possibly other innovative devices, and medicines. That these conditions are elusive even in the presence of AIDS prevention programmes has been argued (Campbell 2003) and is also

18 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

evident from the case studies. A host of factors encourage dangerous choices: the appearance-consciousness and relative lack of means of Sadgrove’s Ugandan university students; the strictures that Ghanaian ‘ouest workers’ in Gaborone operate under (van Dyk) or the assertion of masculinity in the context of instable gender relations left behind by labour migration under apartheid (Niehaus). Political strictures are acquiring a new acuteness as Africa moves from the era of AIDS education and palliative treatment into that of antiretroviral treatment (ART). ‘The provision of these drugs presents a challenge for weakened national health systems and their transnational donors, but also an opportunity to pursue religio-political agendas. In south-eastern ‘Tanzania, according to medical workers in the region, the implementation of a US-funded ART programme was put off several times to accommodate the donors’ demands for control over the supply of the drug. Similarly, at the time of writing this introduction, the widows in the village described by Prince are still struggling to obtain the ART, although antiretroviral drugs ought to be available for free since 2006 (thanks to government policy and US American funding through GAP and PEPFAR, which in turn are shaped by a particular version of Christian ideology). These experiences with ART underline the institutional obstacles that obstruct change in official responses to the epidemic; obstacles that ultimately are based in political decisions and economic resources. ‘This situation points to a new set of questions concerning HIV/AIDS and religion: the ways in which HIV treatment campaigns and ART drugs engage with religious ideologies and religious subjectivities, on a personal and social level, as well as on the level of HIV policy and politics, both national and global. ART, subjects, and subjection

The possibility of HIV testing so as to take action to obtain drugs and access health care in order to live with HIV has created new opportunities for religious exhortation as well as self-reflection. ‘The suggestion that the experience of a positive diagnosis and subsequent reorientation towards living with HIV (and, hopefully, ARVs) could ‘call forth new selves’ (in Neuyen’s phrase), in particular in connection with the Pentecostal experience of being ‘born again’, caused some discussion among the editors. It is rooted in Foucault’s insistence that power

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 19 regimes work on people not only by limiting and controlling, but also by cultivating and shaping them. Moreover, there can be little doubt that the adaptation to living with HIV has to be, and being born again can be, a profound reorientation, and one relevant to what Foucault called the ‘care of the self’. But, as Sadgrove and van Dyk remind us in their chapters on Pentecostals in Kampala, Uganda, and Gaborone, Botswana, being born again may sometimes be predominantly about scaling existing social hierarchies, formulaic, pragmatic and not particularly personal. More generally, it is problematic to speak of new selves without demonstrating how they are different from those selves that Africans surely

have long cultivated, unless we want to treat ‘the self’ as a cultural category simply absent in certain contexts. Much recent African ethnography (e.g. Lambeck and Strathern 1998; Piot 1999; Helle-Valle 2004; Niehaus 2002; Geissler & Prince 2007, 2009, in press) draws upon older anthropological work on African personhood and Melanesian sociality, to explore differences between the notion of ‘self’ and ‘individual’ as cultivated in the West since the enlightenment, and more relational (for some accounts ‘dividual’) modes of socially producing persons. Implicit

to this differentiation between western and non-western personhood can be a problematic assumption of general historical change from more relational to more individual personhood, from ‘pre-modern’ to modern; ‘non-western’ to ‘western’. ‘To avoid this a-historical dichotomisation, one needs to keep in mind that mages of difference, like ‘individual’ and ‘dividual’ personhood, or social ‘flows’ vs. bounded ‘selves’, are not entities that can be had by themselves. ‘hey serve as pairs, as ‘convenient fictions’, as Strathern had it, to prize open the complex social and cultural negotiations that occur when concepts, terminology and practices originating in vastly different social, cultural and political-economic settings are articulated

upon one another. It would be obvious nonsense to claim that HIV education brought selves to previously selfless peoples—this would reproduce century old stereotypes of Africa, misrepresent the complexity of personhood anywhere, and grossly overestimate the capacity of external intervention, be it capitalism, mission, or HIV programmes.

At the same time, there can be no doubt that religious programmes that encourage adherents to cut generative and genealogical ties (such as described by van Dijk), economic projects that enforce accumulation and private property, or an HIV training to exercise self-control and choice (Burchard), pose new questions in social settings in which

20 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

procreative relations of gender and generation are fundamental to identity, or in which sharing is considered not only morally superior, but vital and generative (Prince). To understand the resulting negotiations and connect them back

to questions of power and dependency, a focus on the making of subjectivities can be useful. ‘The aim is not to reify imagined ‘cultural’ differences between Africa and the West, or to exaggerate the impact of pharmaceuticals and their providers into totalising new regimes of

sovereignty and citizenship. Rather it is to study the new formations that emerge between new medical problems and solutions, old and new

forms of government, and the bodies of citizens and sufferers. ‘The extent to which these formations involve an examination and reshaping of selves or subjectivities unsurprisingly varies greatly between places and among persons. Discussing the effects of ‘western’ and especially missionary healthcare regimes in colonial Africa, Megan Vaughan once warned against overly quick assertions of subject-formation through medical rationali-

ties (1991). ‘hese medical systems, she argued, were so limited, and their categories for imagining Africans as persons so coarse, distant, approximate, that very little can be said on the basis of the systems’ pronouncements about if and how they interacted with the medical subjects’ personhood. Present levels of medical and especially pharmaceutical intervention in Africa are of course much more intense than at the (colonial) time studied by Vaughan and, maybe more importantly, they are much more focused (namely on HIV) and centralised (notably in the US government’s initiatives). Nevertheless, Vaughan’s qualifica-

tion of a straight “Foucauldian’ approach is well kept in mind when discussing current changes of subjectivity and personhood in Africa. We have to establish more clearly in which ways medical intervention in Africa has actually changed since the colonial period—especially given that health services remain so woefully limited—how, in different

settings, discourses are articulated upon lives, and how new medical and governmental technologies are deployed. Among the present authors, Isak Niehaus’s account of parallels between attitudes to leprosy and AIDS in the South African lowveld suggests continuities between colonial medical interventions and imaginaries, and the present. Likewise, colonial sleeping sickness epidemics, their effect on people’s imagination, and the control measures against

them could be said to prefigure certain traits of HIV pandemic and policy. Such historical continuities should lead us to ask about the

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 21 more subtle differences between past and present, rather than propose wholesale new social formations. ‘The apparent continuities evoked by Niehaus form a striking contrast with Burchard’s observations from urban South Africa, and Nguyen’s from Burkina Faso, that deal with the experience of ‘living positively’. These two papers most clearly suggest that such new subjectivities (to

use a term suggesting something less fundamental and more easily malleable than ‘self”) are emerging. Among Pentecostals in Uganda, Sadgrove observes a more gingerly and intermittent move towards practicing new forms of care of the self, while Christiansen observes the emergence of a new kind of social persona among widows. In Zanzibar, though, Beckmann shows that Zanzibari Muslims often cope with being HIV+ by shifting from speaking of infection as divine punishment for individual transgression to speaking of a trial which

HIV-sufferers undergo on behalf of the entire community that has fallen short of God’s ideals. ‘Uhis allows the victims to envision a place for themselves within a Muslim milieu that continues to display very judgmental attitudes towards them; it enables them to keep their selves, as 1t were, within normal range. Counselling, Rhetoric and extraversion: ‘performing’ survwal jor Western audvences?

Another way of looking at the new forms of subjectivity that emerge at the interstices between religion and AIDS would be in terms of performance, emphasising not so much processes of self-making, but the representation of new selves to specific audiences, aiming for specific effects. Now that AIDS has become a treatable condition, 1t shares in the fundamental problem of all medical conditions in Africa: how to make treatment available. ‘The debates about ART in South Africa, claimed

by some with reference to universal rights, and questioned by others, including the president, as a political risk and a possible deflection of attention from the political-economic causes of the epidemic (see Fassin 2007), have made it abundantly clear that even in Africa’s wealthiest nation, AIDS sufferers cannot rely on their government to provide ART and, more importantly, that governments and citizens rely upon multiple

other agencies—non-governmental as a well as bilateral and international, public as well as charitable and private—to access treatment. ART thus implies new dependencies and threats, which are reflected in

22 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER

discussions and rumours about standards of treatment, and which can be interpreted as Nguyen does, as generating ‘therapeutic citizenships’ that might replace older attachments and responsibilities. People (patients and governments) in Africa are dependent upon ‘donors’ beyond their control to survive. It would thus not seem an excessive simplification if we assumed that they try, through their behaviour, to harness these powers. Nguyen, for example, observes the interaction between HIV positive people and faith-based counsellors in Burkina Faso. He argues that people are living up to drug providers’ ideals of ‘living positively’ so as to encourage ARV provision; performing

survival to the donors to keep them donating. ‘hey use standardised confessional forms with religious connotations to create an appealing performance. Such an orientation towards an overseas audience is not new: the performance of ‘western’ values and styles has been part of colonial and post-colonial sociality throughout the past century, conflating changing subjectivities, creative mimesis and utilitarian manipulation (see e.g. Mutongi 2007). What is new 1s the fact that the success of these performances directly determines survival. ‘Uhe stakes are high, and so is pressure to perform well. The tendency towards externalising display is not limited to AIDS. Recently, Kenyan youths have been performing violence for the cameras,

and the dependence of African AIDS victims on overseas providers brings to mind Bayart’s exploration of the ‘extraversion’ of African polities: the long-standing ability of elites not Just to depend on, but to manipulate inflows from abroad (Bayart 1993). ‘his reminds us that the manipulation of the provision of ARVs, including their exploitation for extraneous ends, 1s always a possibility. For example one might

argue that faith-based counsellors, the newest and fastest morphing new African healthcare care profession (if this is the right word) have taken shape precisely at the intersection of HIV, NGOs and religious commitments, as well as between new Christian selves, new styles of ‘positive living’ and the performative demands of a new labour market funded by broadly faith based overseas HIV aid (Prince 2008). The contributions to this volume, then, are forays into an exciting new field of enquiry: into the shifting outlines of Africans’ lives during an age of HIV and I'BOs, non-governmental politics and politicised aid.

They draw attention to the creative powers released by the struggle to live with HIV, but they also remind us that HIV 1s but one factor in the processes that reshape African socialities and polities. In their diversity, they make clear that no one academic narrative can do justice

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 23 to these processes of change. Nevertheless, for the present authors the multi-stranded narratives of religion, with their ambiguities and their combination of explicit discourses and implicit, embedded everyday forms, have proven a valuable starting point for the understanding of Africa in the times of AIDS.' References

Bayart, J. F. 1993. The state in Africa: the poltics of the belly. London and New York: Longman. Becker, Felicitas. 2008. Becoming Muslim in Mainland Tanzania. Oxford and London: Oxford University Press and the British Academy. Benn, Christoph. 2000. ‘Dogmatische Predigt, pragmatische Hilfe? Die Kirchen und die Bekampfung von AIDS in Afrika’. Der Uberblick 36.3, 58-63. Boddy, Janice. 1988. ‘Spirits and Selves in Northern Sudan: ‘The Cultural Therapeutics of Possession and ‘Trance’. American Ethnologist 15.1, 4-27. Campbell, Caroline. 2003. ‘Letting them de’: why HIV/AIDS prevention programmes fail. Oxford: James Currey. Cattell, Maria G. 1992. ‘Praise the Lord and Say No to Men: Older Women Empowering ‘Themselves in Samia, Kenya’. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 7, 307-30. Cohen, D. W. and E. S. A. Odhiambo. 1989. Siaya.UVhe Historical Anthropology of an African Landscape. Nairobi, Heineman Kenya. Comaroff, Jean and John Comaroff. 1991. Of Revelation and Revolution volume 1: Christianity,

Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa. Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press. ——. (eds.). 1993. Modernity and Its Malcontents: Ritual and Power in Postcolonial Africa.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Deutsch, Jan-Georg, Peter Probst and Heike Schmidt (eds.). 2002. African Modernities: Entangled Meanings in Current Debate. Oxford: James Currey. De Waal, Alex. 2006. AZDS and power: why there is no political crisis—yet. London: Zed Books.

Eickelman, Dale and James Piscatori. 1996. Muslim politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ellis, S. and G. ‘Ter Haar. 2004. Worlds of Power. Religious Thought and Pohtical Practice in

Afnca. London, Hurst & Co. Englund, H. and J. Leach. 2000. “Ethnography and the meta-narratives of modernity.’ Current Anthropology 41(2): 225-248.

Epstein, Helen. 2007. The invisible cure: Africa, the West, and the fight against AIDS. New

York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Fassin, D. 2007. When Bodies Remember: experiences and politics of AIDS in South Africa.

Berkley, University of California Press. Ferguson, James. 1999. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Kambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

' In order to further the study of these issues, an interdisciplinary network dedicated to ‘Religion and AIDS in Africa’ has been established in a collaboration between the African Studies Centres in Leiden, Cambridge and Copenhagen; to join the network, please contact the chairman, Dr Ryk van Dyk on DIJK [email protected].

24 FELICITAS BECKER & P. WENZEL GEISSLER Ferguson, James. 2006. Global Shadows. Afnca in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham, Duke

University Press. Fields, Karen. 1985. Revwal and Rebellion in Colonial Central Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Geissler P W. & Prince R. J. 2007. Life Seen: ‘Touch and Vision in the Making of Sex in Western Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1(1), 123-149. Giblin, James. 1992. The poltics of environmental control in Northeastern ‘Tanzama, 1840-1940.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Gifford, Paul. 1994. ‘Some Recent Developments in African Christianity’. Afncan Affairs

93.373, 513-34. Heald, S. 1999. ‘The power of sex: reflections on the Caldwell’s ‘African sexuality’ thesis. Manhood and Morality. Sex, Violence, and Ritual in Gisu Society. S. Heald. London

& New York, Routledge: 128-145. Helle-Valle, Jo. 2004. ‘Understanding Sexuality in Africa: Diversity and contextualised dividuality. Re-thinking Sexualites in Africa. S.Arnfred. Uppsala: Nordisk Afrika Institute. Hooper, E. 1999. The River. A Journey back to the source of HIV and AIDS. Harmondsworth,

Penguin. Hunt, N. R. 1999. A Colonial Lexicon. Of Birth Ritual, Medicalisation, and Mobility in the

Congo. Durham & London, Duke UP. [liffe, John. 1979. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ——, 2006. The African AIDS Epidemic: A History. Oxford: James Currey. Kepel, Gilles. 1993. The Revenge of God: The Resurgence of Islam, Christianity and Fudasm in the Modern World. Gambridge: Polity Press. Lambeck, M. and A. Strathern. 1998. Bodies and Persons. Comparatwe Perspectwes from Africa

and Melanesia. Cambridge, CUP.

Landau, Paul. 1999. ‘Religion and Christian conversion in African history: a new model’. Journal of Religious Mstory 23, 8-30. Latour, B. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. New York, London, ‘Toronto, Sidney, ‘Tokyo,

Singapore, Harvester and Wheatsheaf. Lienhardt, G. 1961. Dwinity and Experience. The Religion of the Dinka. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Islamic Medical Association of Uganda. 1998. ‘AIDS Education through Imams: A Spiritually Motivated Community Effort in Uganda’. Geneva: UNAIDS. Mate, R. 2002. ‘Wombs as God’s Laboratories: Pentecostal Discourses of Femininity in Zimbabwe’. Africa 72.4, 549-68. Makris, G. P. 1996. ‘Slavery, Possession and History: ‘The Construction of the Self among Slave Descendants in the Sudan’. Africa 66.2, 159-182. Marks, Shula and Richard Rathbone. ‘Introduction: the history of the family in Africa’, in Journal of Afncan History 24 (1983), 145-61. Maxwell, D. 1998. ‘“Delivered from the Spirit of Poverty?” Pentecostalism, Prosperity and Modernity in Zimbabwe’. Journal of Religion in Africa 28.3, 350-73.

Meyer, B. 1999. ‘Commodities and the Power of Prayer: Pentecostalist Attitudes towards Consumption in Contemporary Ghana’. In B. Meyer and P. Geschiere (eds.), Globalization and Identity: Dialectics of Flow and Closure. Oxford: Blackwell, 151-176.

Mutongi, K. 2007. Worries of the Heart. Widows, Family and Community in Kenya. Chicago, Chicago University Press. Niehaus, Isaak. 2002. Bodies, heat, and taboos: Conceptualizing modern personhood in the South African lowveld. Ethnology, 41(3): 189-207. Ogden, J. A. 1996. ‘“Producing” Respect: ‘The “Proper Woman” in Postcolonial Kampala’. In: R. Werbner and ‘I: Ranger (eds.), Postcolonial Identities in Africa. London:

Zed Books, 165-92. Ogot, B. A. 1963. ‘British Administration in Central Nyanza District, 1900-1960’. Journal of African History 4, 249-73.

RELIGION AND AIDS IN AFRICA 29 Pels, P. 1999. A Politics of Presence: Contacts between Missionaries and Waluguru in Late Colonial Tanganyika. Amsterdam: Harwood/Gordon & Breach.

Pickle, K., S. CG. Quinn, et al. 2002. ‘HIV/AIDS coverage in Black newspapers, 1991-1996: implications for health communication and health education.’ J Health Commun 7(5): 427-44. Piot, GC. 1999. Remotely Global. Village Modernity in West Africa. Chicago and London,

U of Chicago P. Prince, R. J. 2006. ‘Popular Music and Luo Youth in Western Kenya: Ambiguities of Mobility, Morality and Gender in the Era of AIDS’. In C. Christiansen, M. Utas and H. Vigh (eds.), Navigating Youth, Generating Adulthood: Social Becoming in an African

Context Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute.

Prince, Ruth J. 2008. ‘HIV counsellors in Kenya—the fragmentation of professional knowledge and the continuity of everyday life’. Paper presented at the conference ‘Regimes of care—relations of care’, Cambridge, African Studies Centre, June 6th 2008. Prince R. J. & Geissler, P, W. 2009, in press. The Land is Dying. Contingency, creatwity and conflict in western Kenya. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

Ranger, ‘I. 1992a. ‘Plagues of beasts and men: prophetic responses to epidemic in eastern and southern Africa’. Epidemics and Ideas. Essays on the Perception of Pestilence.

T. Ranger and P. Slack. Gambridge, Cambridge University Press, 241-268. Ranger, TI. O. 1992b. Godly medicine: the ambiguities of medical mission in southeastern Tanzania. The Social Basis of Health and Healing in Africa. S. Feierman and J. M. Janzen. Berkeley, U California P: 256-283. Sanders, Todd. 2001. “Save our Skins: Structural Adjustment, Morality and the Occult in ‘Tanzania’. In H. L. Moore and 'T’ Sanders, Magical Interpretations, Matenal Realities.

London and New York: Routledge, 160-183.

——. 2002. ‘Reflections on two sticks: Gender, sexuality and rainmaking.’ Cahiers Etudes

africanes 166(XLII-2): 285-313.

Schoepf, B. G. 1995. ‘Culture, Sex Research and AIDS Prevention in Africa’, in H. ten Brummelhuis and G. Herdt (eds.), Culture and Sexual Risk: Anthropological Perspectiwes on AIDS. Luxembourg: Gordon and Breach, 1995, 29-52. Setel, P. 1999. A Plague of Paradoxes: AIDS, Culture and Demography in Northern Tanzania.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Turner, V. 1967. ‘The Forest of Symbols. Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, London, Cornell UP. Vaughan, Megan. 1991. Cunng thear ills: colonial power and Afncan ulness. Stanford: Stanford

University Press. Whyte, S. R. 1997. Questioning Misfortune: The Pragmatics of Uncertainty in Eastern Uganda.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wipper, Audrey. 1978. Rural Rebels: A Study of Two Protest Movements in Kenya. Oxford:

Oxford University Press. Yamba, C. Bawa. 1997. ‘Cosmologies in ‘Turmoil: Witchcraft and Aids in Chiawa, Zambia’. Africa 67.2, 200-23.

Blank page

NEW DEPARTURES IN CHRISTIAN CONGREGATIONS OF LONG STANDING

Blank page

THE RISE OF OCCULT POWERS, AIDS AND THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH IN WESTERN UGANDA Heike Behrend Introduction

When I came to ‘looro in western Uganda in 1998, I was more than surprised to find people talking about abali wawaniu, man-eaters or cannibals. Women and men from all social classes, in towns as well as in rural areas, complained that cannibals were killing and eating their relatives, friends and neighbours. ‘These cannibals likewise were said to be witches, because they first bewitched their victims so that they died.

Then, after the burial, cannibals resurrected the dead not so much to work for them as zombies (cf. Ardener 1970, Fisiy and Geschiere 2001: 241) but to eat them at a sinister banquet with other cannibals. ‘Uhus, these cannibals were part of a radicalised witchcraft discourse: whereas witches kill only once, cannibals kill twice, doubling and prolonging

the horror of death. While, in the 1970s, man-eaters were still assumed to be confined to Kajura in Mwenge district, 1t was said that since the 1980s they had greatly multiplied and spread into other regions. In 1998, I was told that cannibals were everywhere; in some regions where they had become epidemic a sort of ‘internal terror’ (Lonsdale 1992: 355) reigned, a secret war, In which anyone you encountered could be an enemy, prepared to kill and eat you.!

' IT am grateful to Paul Gifford and the participants in the Seminar on Faith and Aids in Africa, organised by SOAS and the School of Hygiene and ‘Tropical Medicine, in London for their helpful comments. In addition, I would like to thank Brad Weiss for his review and kind critical remarks. Furthermore, my thanks go to the VW-Foundation and the Special Research Program 427 for having generously financed my research.

30 HEIKE BEHREND Occult forces on the rise

In recent years, religion and even the ‘religious’ have resurfaced in various parts of the world with unprecedented force. Various religious groups, Islamic as well as Christian, entered the political arena, challenging the notion that secular society and the modern nation state can provide the moral fibre that unites national communities ( Juergensmeyer 2000: 225). Responding to the forces of globalisation, the liberalisation of the market, the decline of states and the emergence of new media in the last two decades, political theologies have emerged that forcefully counter the western concept of religion as a private individual matter. The ‘return of the religious’ has also become the object of a complex debate among philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, historians of religion and anthropologists (for example de Vries and Weber 2001), reinforcing the view that the more or less uncontested

narrative of a secular modernity had obscured the fact that in most historical formations the political in various ways had been contingent upon the authority or explicit sanctions of a dominant religion. Indeed,

the clear-cut separation between the domains of the religious and the state became problematic and instead the interconnectedness and complementarity of both domains have been placed in the foreground (Derrida 2001). Among anthropologists working in Africa, the idea of ‘a return of the religious’, however, was shifted more to themes like ‘the actuality of evil and ‘the rise of occult forces’. Yet, like their colleagues in other disciplines, most anthropologists took as the main causes for the dramatic rise in occult powers the global capitalism unleashed by neoliberalism and the breakdown of the public sphere in postcolonial states producing new exclusions, increasing poverty, illicit accumulations, and thereby radical inequalities’ (Comaroff and Comaroff, 1993, 1999). While some authors stress the consequences of the Structural Adjustment Program

of the IMF and the World Bank in ‘freeing the market’ and thereby freeing also the possibilities for marketing the occult (Sanders 2001: 162), for others it 1s, above all, illicit accumulation and the exploitative

extraction of labour and life-force that leads to the rise of witchcraft

* Although the question of whether witchcraft and the resort to occult forces is increasing in contemporary Africa is difficult to answer because the data base is rather