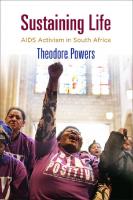

Sustaining Life: AIDS Activism in South Africa 9780812296853

Through participant observation and in-depth interviews, Sustaining Life explores how the South African AIDS movement tr

166 102 2MB

English Pages 280 [257] Year 2020

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

Sustaining Life

PENNSYLVANIA STUDIES IN HUMAN RIGHTS Bert B. Lockwood, Series Editor A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Sustaining Life AIDS Activism in South Africa

Theodore Powers

U N I V E R S I T Y O F P E N N S Y LVA N I A P R E S S PHIL ADELPHIA

Copyright © 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 www.upenn.edu/pennpress Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-8122-5200-2

For Kat, Emma, and Leo

CONTENTS

Preface

ix

List of Abbreviations

xv

Introduction. People, Pathogens, and Power: Situating the South African HIV/AIDS Epidemic

1

Chapter 1. Contact, Colonization, and Apartheid: South African Social Formations in Historical Perspective

23

Chapter 2. The Political History of South African HIV/AIDS Activism

53

Chapter 3. Occupying the State: HIV/AIDS Activism and the South African National AIDS Council

82

Chapter 4. A Policy Redirected: Transnational Donor Capital and Treatment Access in the Western Cape Province

104

Chapter 5. Community Health Activism, AIDS Dissidence, and Local HIV/AIDS Politics in Khayelitsha

134

Chapter 6. People Are the State: Activism, Access, and Transformation

158

Afterword. After Treatment Access: An Epidemic Unresolved

180

Notes

195

References

207

Index

229

PREFACE

Anthropology, it is often said, attempts to bridge social and cultural difference in order to make ideas and practices from the Global South seem more familiar to those living in the Global North. In this characterization, anthropologists are seen to act as mediators who engage with “the other” in order to make their lives more comprehensible to northern publics. In doing so, anthropologists are imagined as bringing a set of academic practices to bear relative to the question of cultural variation by brandishing an expertise of a particular sort. Inherent in this formulation is a hierarchy regarding academic knowledge and an understanding of the broader context within which ideas and practices are situated, purportedly the purview of the anthropologist. The situation that I encountered as I began research on the politics of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic did not cohere with the generalized understanding of anthropological fieldwork described above. If anything, the hierarchy of expertise relative to the HIV/AIDS epidemic was reversed, as some research participants had contributed to publications in esteemed academic journals such as the Lancet. But, as I was to learn, the inverse relationship between researcher and expertise was not isolated to debates on epidemiology; it extended far beyond to the social dynamics that drove HIV infection, the politics that limited the public sector HIV/AIDS response, and the material privations that community-based HIV/AIDS activists navigated as part of their everyday lives. Indeed, while my name may appear on the cover of this book, it is the knowledge and experiences of those who opened their lives to me that has provided the basis for the ethnography that follows. I was, and remain, a student of South African society, and those whose lives are outlined in this book are, and continue to be, my teachers. This book would not have been possible without their generosity, patience, and understanding as I learned about the everyday challenges of HIV/AIDS and the political struggle required to expand HIV/AIDS treatment access in South Africa. However, the contributions of

x

Preface

my research participants were not limited to the gathering of data. They were also central to the research design that I employed in my work. As I describe in detail in Chapter 1, I followed the life pathways of research participants in order to locate field sites where politics, policy, and HIV/AIDS treatment access were negotiated. Thus, rather than a predetermined conception of the field and research sites, my project grew out of the lived experiences of those navigating the landscape of HIV/AIDS politics in South Africa. Following people involved with the campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access shed light onto how transnational forces articulate with HIV/AIDS politics, how debates on AIDS dissidence manifested in the townships of the Cape Flats, and how HIV/AIDS activists occupied the state to transform treatment access. This project—and the insights that it offers relative to academic debates on transnationalism, social movements, and the state—largely belongs to those who fought for HIV/AIDS treatment access in South Africa. I offer my deep thanks for their contributions, and I hope that I have done justice to their life histories and political campaigns in the pages that follow. The process of developing and finalizing this manuscript has led me to understand that writing a book is a social act that involves the direct support of a wide network of advisors, mentors, colleagues, and family members. I first encountered the core theoretical questions that this book engages with during my undergraduate studies at Bates College. There, under the guidance of Kiran Asher and Peter VonDoepp, I undertook a senior thesis that engaged with debates on globalization, the transnational movement of cultural practices, and political economy. Both Kiran and Peter have continued to offer their mentorship and support, and I offer my thanks to them. I am deeply indebted to faculty members in the Department of Anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center for the rigorous training and professional guidance that I received over the course of my graduate studies. Particular thanks are in order to the members of my doctoral committee, which included Don Robotham, Ida Susser, and David Harvey. Each of my graduate advisors provided me with direction, critique, and encouragement as this project went through various phases. This book—and the ethnographic contributions that it offers—is reflective of the theoretical and professional direction that was provided by the members of my doctoral committee. Here I offer my full and unreserved thanks for their training, mentorship, and guidance. Thanks are also in order to other members of the department who provided mentorship and support during my graduate studies, including Michael Blim, Gerald Creed, Kate Crehan, Louise Lennihan, Shirley Lindenbaum, Jeff Maskovsky,

Preface

xi

and Katherine Verdery. I must also thank Ellen DeRiso for her guidance, support, and friendship as I navigated the institutional infrastructure of a large public university. I also offer my gratitude to T. Dunbar Moodie for reading an early version of this book and offering insightful feedback on areas for further development. In addition to my academic training in the US, I have been privileged to work with and learn from members of the South African academic community. I am grateful for the support offered by Nicoli Nattrass during my field research, as she generously offered institutional affiliation, personal support, and critical feedback. During my time as a visiting researcher at the Aids and Society Research Unit, a part of the Centre for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town, I met colleagues who offered their support and insight on the politics of HIV/AIDS including Eduard Grebe, Elizabeth Mills, and Atheendar Venkataramani. I have also received encouragement and guidance from South African scholars including Patrick Bond, Bill Freund, Steven Friedman, Rob Gordon, Hylton White, Mugsy Spiegel, David Sanders, Zolani Ngwane, Devin Pillay, and Jeremy Seekings. My thanks to all those listed, and those who I may have unintentionally omitted, for their support of my work. This project has also benefitted from further training and mentorship that I received during the course of a two-year postdoctoral fellowship with the Human Economy Programme at the University of Pretoria. My thinking on HIV/AIDS politics continued to evolve in the vibrant academic environment cultivated by program codirectors Keith Hart and John Sharp. The conceptual approach toward transnational sociopolitical dynamics that I developed during my postdoctoral fellowship was buttressed by Keith’s uplifting positivity and support and by John’s probing inquiries. Thanks also to those whose ideas animated the active seminars within which some of the core ideas of this book were molded, including Theo Rakopoulos, Tijo Salverda, Doreen Gordon, Camille Sutton-Brown, Jürgen Schraten, Albert Farré, Juliana Braz Dias, Busani Mpofu, Mallika Shakya, Booker Magure, Vito Laterza, Marina Martin, and Francisco Ngongo. My time in Pretoria included a period when I worked as a senior lecturer in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology. My thanks to all those who made my experience at the University of Pretoria productive, enjoyable, and irreplaceable relative to the development of this work. Thanks to Innocent Pikirayi, John Sharp, Detlev Krige, Fraser McNeil, Ceri Ashley, and Jimmy Pieterse for their collegiality, support, and friendship. I would also like

xii

Preface

to thank the late Lynnette Holtzhausen for her friendship and guidance as I navigated the process of securing work permits, acquiring visas, and learning the administrative norms of a South African academic institution. While core concepts and approach were developed during my doctoral and postdoctoral studies, this book was written in its entirety during my time at the University of Iowa, where I benefitted from the active support of senior colleagues. In particular, I offer my deepest thanks to Ellen Lewin, who read both early and refined chapter drafts, offering extensive and invaluable feedback and guidance on the narrative that became this book. Meena Khandelwal was also an essential source of support, offering guidance and reading chapter drafts as I navigated university life as a junior faculty member, developed articles, and wrote a book manuscript. I cannot thank either of my aforementioned colleagues enough for their mentorship and guidance. In addition, I want to thank Paul Greenough and Michael Chibnik for their input as I navigated the world of book publishing for the first time. Their feedback on early drafts of the book proposal helped me to better understand a different domain of academic publishing. I also benefitted from the active encouragement and support of other members of the Department of Anthropology, including James Enloe, Cynthia Chou, Andrew Kitchen, Matthew Hill, Margaret Beck, Elana Buch, Emily Wentzell, Scott Schnell, Laurie Graham, Katina Lillios, Heidi Lung, Bob Franciscus, Erica Prussing, and Russ Ciochon. Faculty members affiliated with the Global Health Studies Program were another source of guidance and support, and I offer my gratitude to Christopher Squier, Mariola Espinosa, Maureen McCue, Robin Paetzold, Mary Wilson, Jeanine Abrons, and Claudia Corwin. I would also like to thank Beverly Poduska, Shari Knight, Allison Rockwell, and Karmen Berger for their guidance and support in avoiding administrative pitfalls as I navigated the tenure track at the University of Iowa. Funding from several sources supported the process of developing my early research and this book project. An Africanist Doctoral Fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, augmented by a grant from CUNY, supported my fieldwork. However, a key source of funding and support was Ida Susser’s research initiative South Africa’s Civil Society Organizations and AIDS Treatment Access, funded by the National Science Foundation. Regarding this, as in many other matters of professional development, my deep thanks to Ida. A fellowship at the Center for Place, Culture and Politics at CUNY supported the early stages of writing. In addition, a writing fellowship awarded through the City University of New York was essential to supporting the process of finalizing the work that eventually became this book.

Preface

xiii

As is often the case, the book that follows has been completely rewritten and bears little resemblance to its first iteration. Indeed, follow-up research supported by the Human Economy Programme at the University of Pretoria was essential for re-examining my approach to understanding the politics of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. My thanks to both Keith Hart and John Sharp for their support of my continued research on the local politics of HIV/AIDS, public health, and treatment access in South Africa. The process of writing the book was supported by the University of Iowa granting a Flexible Load Assignment during the fall 2017 semester, which enabled me to finalize necessary revisions to the manuscript without the usual rigors of university teaching. In addition, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Iowa helped to finalize the book through subvention funding to cover the cost of indexing and image rights. I would also like to thank Peter Agree and Lily Palladino for their supportive editorial approach as I navigated the review process at the University of Pennsylvania Press. Last but certainly not least, my family has shown me endless support as I have worked through my studies and the early career stages of academia. Between completing my doctoral studies, navigating a postdoctoral fellowship, securing a visiting position, and life on the tenure track, my family has seen me through the ups and downs that inevitably accompany this process. My mother, Claudia; father, Richard; brothers Greg, Matt, and Thurston; stepmother Darcy; and sister Zoe have offered their encouragement and unconditional love throughout. I would also like to thank my godparents, Bruce and Jill Winningham, for their support and guidance over the years. In addition, my now-deceased grandmother Claudia and grandfather James were always extremely supportive as I worked through my graduate studies, and I offer them my gratitude. While everyone discussed above has helped to bring this book into existence in some way, it has been the support of my loving, intelligent, and beautiful partner Kat that has carried me through the peaks and valleys of the writing process. In addition to bringing positivity, perspective, and light to each day of our lives together, Kat has also brought our daughter Emma and son Leo into our lives, and they have provided me with new perspective on life and ceaseless joy. My endless thanks are in order to Kat for tolerating my mercurial tendencies and for her unconditional love as I worked through the many steps involved in securing one’s livelihood as an early-career academic. Thank you for standing by me as this project carried on; we did it.

ABBREVIATIONS

ABC AIDS ALN ALP ANC ART ARVs AZT BCM BEE CALS CBOs COSATU Eskom GASA GDP GEAR GLOW HAART HIV IMF Iscor LRC MK MSAT MSF NAPWA NEDLAC

Abstinence, Be Faithful, and Condomize Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome AIDS Legal Network AIDS Law Project African National Congress Antiretroviral Therapy Antiretroviral Drugs Azidothymidine Black Consciousness Movement Black Economic Empowerment Centre for Applied Legal Studies Community-Based Organizations Congress of South African Trade Unions Electricity Supply Commission Gay Association of South Africa Gross Domestic Product Growth, Employment, and Redistribution Macroeconomic Strategy Gay and Lesbian Organization of the Witwatersrand Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Human Immunodeficiency Virus International Monetary Fund Iron and Steel Corporation Legal Resources Centre Umkhonto we Size (Spear of the Nation) Multi-Sectoral Action Team Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders) National Association of People Living with AIDS National Economic Development and Labour Council

xvi

NGO NPPHCN NSP OLGA PMTCT PSP RDP SACP SANAC SANCO STIs TAC TB UDF USAID VCT WC-Nacosa WHO

Nongovernmental Organization National Progressive Primary Healthcare Network National Strategic Plan Organization of Lesbian and Gay Activists Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (of HIV) Provincial Strategic Plan Reconstruction and Development Programme South African Communist Party South African National AIDS Council South African National Civics Organisation Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Action Campaign Tuberculosis United Democratic Front United States Agency for International Development Voluntary Counseling and Testing Western Cape Networking AIDS Coalition of South Africa World Health Organization

INTRODUC TION

People, Pathogens, and Power Situating the South African HIV/AIDS Epidemic

Matamela shook his head as he spoke to me, a wistful expression coming over his face.1 He turned and looked out of the window, pensively stroking his beard for a moment, deep in thought. Matamela was a leading activist for the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) at the organization’s district office in Khayelitsha, a black urban township approximately twenty miles from Cape Town’s city center. TAC’s district office was housed in an off-white building in a shopping complex adjacent to the Nonkqubela railway station, and it was the base of operations for community-oriented activities designed to limit the spread and impact of HIV/AIDS in the township. As night fell we leaned toward the cracked windows, hoping to catch the last moments of light. Matamela adopted an urgent tone as he spoke of the daily obstacles faced by those accessing HIV/AIDS services in the South African public health sector. If you go out and you say to people, “We are coming to your community to talk about VCT [voluntary counseling and testing for HIV/AIDS]. Come out and go and have voluntary counseling and testing.” And people go to the clinic, and wait hours to go do VCT, and at the end of the day, they do not want to go to the VCT anymore, then there’s a problem there. That quality of service is compromised. Because no one wants to wait for two hours, three hours just for testing for HIV. No one wants to wait. Because you will wait, and at some point [you will be] be told that, “Come tomorrow, because we are about to close down now.” In some instances, you are being told that there is no medication for this particular illness that you are suffering from. It creates a problem.

2

Introduction

Emphasizing how often people waited in line for hours but were unable to see a doctor, Matamela painted a picture of underresourced and understaffed public health services in a community where nearly one in three pregnant women are HIV positive. In this and other conversations, Matamela attributed the continuing challenges of HIV to the socioeconomic conditions created by colonization, segregation, and apartheid. His was a sobering analysis of the world’s largest HIV/AIDS epidemic. I met Matamela during one of my first visits to TAC’s office in Khayelitsha. A tall Xhosa-speaking black South African in his mid-thirties, his expression alternated between a broad smile and a searing gaze. As one of the senior activists at the district office, Matamela was often too busy to sit and discuss the broader politics of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic. That night, another activist had left with the only set of keys, and we had been locked in the office due to a power failure in the township. As was the case for many homes and offices in South Africa, the TAC office had a steel gate and a locking door that had been installed to deter would-be intruders, imagined or real. As I had realized the first time I had locked a gate of this kind, the barrier not only prevents someone from entering but also restricts the movement of those inside. Now, fortunately for me, being locked in the office enabled me to learn more about Matamela’s background and his experiences confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Matamela was born and raised in the Cape Flats, a series of townships that stretch out from the Cape Town city center across a broad floodplain. Brought up in a working-class household, he was radicalized by the Soweto student uprising in 1976 and the subsequent intensification of government violence. During the late apartheid era, Matamela was a member of the PanAfrican Congress, an African nationalist organization that was part of the anti-apartheid movement. He also helped to found TAC and subsequently served as a leading member for the district office and the organization as a whole. As we discussed the political history of the epidemic, Matamela underscored the significance of a TAC protest at the International AIDS Conference held in Toronto in 2006. The South African government delegation to the conference, which included the nation’s minister of health, Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, had placed garlic, lemon, and beetroot alongside antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) in their display of HIV/AIDS treatments. Protesters from TAC, including Matamela, confronted the delegation for suggesting equivalence between homeopathic remedies and ARVs. The health minister was part of a powerful dissident faction within the ruling African National Congress (ANC) that questioned the underlying science

People, Pathogens, and Power

3

linking HIV to AIDS. The faction critiqued the efficacy and toxicity of ARVs, challenged the characterization of Africans as oversexualized and unable to govern themselves, and condemned the global pharmaceutical industry for profiting from African illnesses. The messages emanating from ANC members in high government positions had a tangible effect on perceptions of HIV/ AIDS within TAC’s district branch in Khayelitsha. Matamela recounted: The problem is—with AIDS, which emanates from poverty—people deny completely that they are having HIV. And these people are going to deny that there is an existence of HIV, so there is no point for them to use condoms. So the rate of infection becomes high. The death rate is huge. There are people who are delaying to start treatment. There are people in TAC who have been delaying their treatment. You ask them “why?” [and] they say that they are afraid. “Of what? Of drugs, why?” “Because the minister is saying this.” Tell me, if people in TAC, who are more informed, are having those doubts, how much more for people who aren’t informed, who are listening only on the radio, watching the television, catching those messages from the minister of health and from the president? I stand by what I said. The president and minister of health, they need to be charged for genocide. Many people have died from AIDS because of their confusing messages. Matamela was not alone in offering a harsh assessment of the AIDSdissident faction within the ruling party and its effects on South African society. Its obfuscating statements on the relationship between HIV and AIDS and critiques of orthodox biomedical HIV/AIDS treatments provoked a transnational response that included American and European HIV/AIDS activists, scientists, academics, and international organizations. Within South Africa, TAC was at the forefront of the South African HIV/AIDS movement, confronting government inaction on access to HIV/AIDS treatment and highlighting AIDS-dissident attempts to limit the public sector response to the epidemic. But even an organization leading the campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access was not immune to the broader social effects of AIDS dissidence. A brief window of political opportunity opened because the HIV/AIDS movement’s confrontation with South African AIDS dissidents in Toronto brought intensified international attention and the minister of health left office on sick leave in the aftermath of the protest. Over the next several months, HIV/AIDS activists, including Matamela, worked with government

4

Introduction

officials to develop a new HIV/AIDS policy and revamp national health institutions to include input from the HIV/AIDS movement. Together, they made significant progress in laying the groundwork for expanding HIV/AIDS treatment access. South African activists’ participation in the transnational HIV/AIDS movement and their convergence at strategic sites was decisive for HIV/AIDS politics in South Africa, influencing sociopolitical dynamics and shaping the campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment, often in unpredictable ways. Focusing on activists such as Matamela, this book tells the story of how the South African HIV/AIDS movement transformed public health institutions and enabled access to HIV/ AIDS treatment, thereby sustaining the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS. Based on extended participant observation and in-depth interviews with members of the movement, I trace how the political principles of the anti-apartheid struggle were leveraged to build a broad coalition that changed national policy and institutions to increase access to HIV/AIDS treatment. From the historical roots of HIV/AIDS activism in the struggle for African liberation to the everyday work of community education in Khayelitsha, I show how people and organizations negotiated access to treatment in South Africa. Sustaining Life, then, offers an on-the-ground ethnographic analysis of the ways that HIV/AIDS activists built alliances, developed new policy, and transformed national health institutions to increase access to HIV/AIDS treatment. In analyzing how encounters among activists, state health administrators, and people living with HIV/AIDS transformed access to treatment in South Africa, the book addresses three key questions: How were the activists of the South African HIV/AIDS movement able to overcome an AIDSdissident faction that was backed by government power? How exactly were state health institutions and HIV/AIDS policy transformed to increase public sector access to treatment? How should the South African campaign for treatment access inform academic debates on social movements, transnationalism, and the state, and what insights does it provide for health care activism? To answer these questions, my account tracks the activities of the South African HIV/AIDS movement in space, through time, and across the institutional levels of the state. Having conducted research at multiple field sites, I link social process across institutional levels and identify important sociopolitical “hot spots” where the work of transforming life possibilities for people living with HIV/AIDS unfolded. As South African HIV/AIDS activists secured the right to health for HIV-positive people, they encountered many obstacles, including a powerful bloc of ANC leaders, dissidents who promulgated the

People, Pathogens, and Power

5

virtues of alternative HIV/AIDS treatment and obfuscated the scientific link between HIV and AIDS. In order to understand how and why the political contestation over HIV/AIDS unfolded as it did, it is necessary to first situate the epidemic within its global and regional context, and within the circuits of social inequality that pervade contemporary South African society.

HIV/AIDS, Social Inequality, and the Global South The global HIV/AIDS epidemic is a phenomenon that is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, contravening expectation and assumption as it manifests and necessitating a reconsideration of the foundational categories through which social scientists understand the world. The epidemic is intensely public, as evidenced through contentious debates on sexuality and public sector programs that address its social impact. Yet it is also private, via the networks of intimacy through which it is spread and through the intellectual property rights that govern access to life-extending medication (Thornton 2008). The epidemic transgresses the analytical categories of academic and social thought while exerting violence on the bodies of poor and working-class people across the world (Farmer 1992, 2004). The HIV/AIDS epidemic expanded alongside a process of increased political, economic, social, and cultural integration— what has come to be called globalization—that occurred in the latter half of the twentieth century. Characterized as a disease of the global system, the spread of HIV/AIDS is linked to several dynamics associated with contemporary globalization, including increased population movement, growing connectivity between the world’s regions, and mounting levels of socioeconomic inequality (Altman 2001; Benatar 2001; Baer et al. 2003). Starting in the 1980s, the imposition of stabilization and structural adjustment programs by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank influenced the expansion of poverty, illness, and HIV/AIDS across the Global South. These programs mandated the slashing of state spending on health, education, food subsidies, and social services to secure debt repayment; at the same time trade liberalization and currency devaluation opened recently decolonized societies to economic competition with the industrialized societies of the Global North (Pfeiffer and Chapman 2010). Structural adjustment was followed by sharp increases in chronic malnutrition, stunted growth, and the numbers of low-birth-weight babies alongside declines in state support and rural incomes (Schoepf et al. 2000). Given these socioeconomic effects, it

6

Introduction

is unsurprising that the implementation of structural adjustment policies, and the “structural violence” that they produced, coincided with the expansion of the African HIV/AIDS epidemic (Farmer 2004). The link between poverty and HIV/AIDS is clear: facing a lack of access to resources, more people turn to survival strategies that spread the virus, and malnutrition compromises the first line of defense against the pathogen, immune systems. Increased poverty, migration, and sex work as well as a decrease in public sector treatment capabilities were the bitter fruit of structural adjustment across the African continent (Sanders and Sambo 1991). As public spending on health was cut across the African continent, the HIV/ AIDS epidemic expanded alongside other infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. The budgetary ramifications of structural adjustment undermined nascent postcolonial health sectors, and the HIV/AIDS epidemic expanded from Central to West Africa before moving into Southern Africa. The South African HIV/AIDS epidemic emerged from a crucible of transnational political, economic, and epidemiological dynamics that reflect the rise of neoliberal globalization. “Neoliberalism” refers to a reemergence of liberal economic theory as an organizing principle for national economies from the 1970s onward.2 Neoliberal theory claims that free markets are the most efficient means of allocating goods and services and that the state should focus on economic growth instead of regulation; put into practice with structural adjustment programs, this means the privatization of state assets and the deregulation of markets. However, the unfettered movement of finance capital has also fomented a “race to the bottom” in global labor standards, declining wage levels for industrial workers, and a decline in corporate taxation levels (Sassen 1990; Robotham 2005). Scholars critique the neoliberal turn by pointing to geographic and demographic shifts in industrial production, rising levels of social inequality, the state’s retreat from providing social services, and the growing political and economic power of elites (Comaroff and Comaroff 2001; Schneider and Susser 2003; Duménil and Lévy 2005; Harvey 2005). Neoliberal reforms were self-imposed in South Africa, but despite being voluntary they too were accompanied by social effects that mirrored the impact of structural adjustment in other societies. Understanding the explosive growth of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic also necessitates engaging with the country’s history of profound inequality, which neoliberal reform exacerbated (Terreblanche 1991). Liberation for black South Africans only arrived with the transition from apartheid

People, Pathogens, and Power

7

in 1990 and democratic elections in 1994. Settler colonization, segregation, and apartheid had produced vastly different socioeconomic conditions for racially defined populations. Over time, material inequalities were embodied in compromised immune systems, chronic malnutrition, and a growing burden of disease among black South Africans (Fassin 2007). Politically produced social inequality led to persistent tuberculosis, syphilis, and HIV/AIDS infections among those who had been deemed subservient to the needs of white South Africans (Platzky and Walker 1985). Indeed, South Africa’s unequal history has had a disproportionately negative effect on the health of black South Africans, a social dynamic that has continued during the post-apartheid era. Preying on bodies ravaged by historic inequality, the South African HIV/ AIDS epidemic has grown to be the world’s largest over the past four decades, having expanded on the back of fiscal austerity, state inaction, and AIDS dissidence. The explosion of the epidemic in the 1990s precipitated the political struggle between the ANC and the HIV/AIDS movement, which critiqued government inaction and the political agenda of AIDS dissidents in the ruling party. On the heels of the country’s first democratic election, the ANC implemented a fiscally austere macroeconomic policy that cut social spending to ensure debt repayment, liberalized trade, and privatized state assets. In short, the ANC imposed a variant of structural adjustment amid the exponential expansion of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic. The limits on treatment access imposed by austerity champions and the ANC’s dissident faction led to the premature deaths of approximately 330,000 South Africans living with HIV/AIDS and shortened the aggregate South African lifespan by 2.65 million years (Chigwedere et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2017). While unfolding within a historically particular context, the growth of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic cannot be disentangled from the broader processes of neoliberal globalization and international activism, which necessitates that the epidemic, and the politics that arose in its wake, be situated within a transnational frame. And while the ANC’s AIDS-dissident faction was inspired by American dissident scientists, it was leading South African politicians that limited access to HIV/AIDS treatment, underscoring the continued importance of state institutions and local actors in HIV/AIDS politics. How can the global influences and local actions that drove the South African epidemic be understood? Contemporary anthropological debates on globalization and transnationalism have focused on movement and context as particularly significant for making sense of sociocultural dynamics in an interconnected world.

8

Introduction

Ethnography and Globalization: Navigating Movement and Context Scholars have analyzed how flows—of information, people, money, and even pathogens—are actively reshaping the world alongside neoliberal expansion.3 For example, Arjun Appadurai (1990) conceptualizes the contemporary global era as typified by different sorts of flows. Technology, media, finance, and other domains can be traced as they operate transnationally, bypassing the presumed site of politics, economics, and society: the national state. Appadurai charts the distribution of images, technologies, and people via new patterns of movement, arguing that this approach allows for a more accurate depiction of the world. However, when focusing on flows of people and things, one must be careful not to lose track of the context in which particular sociocultural practices unfold. Studies have drawn attention to how transnational interpersonal networks span societies, organizations, and communities and how some of these networks have taken on state-like roles, such as providing HIV/AIDS treatment to people living with HIV/AIDS in West Africa (Nguyen 2005, 2010). Emphasizing ties across national boundaries, such studies have illuminated the movement of people, pathogens, and pills across disparate social, political, and historical contexts. Other investigations have underscored how international institutions and multinational pharmaceutical corporations influence price-setting dynamics, and how this affects access to HIV/AIDS treatment in the public sector (Biehl 2007, 2008). States do not determine HIV/AIDS treatment availability in isolation; rather, it is the combined efforts of multinational pharmaceutical corporations and the World Trade Organization that set the cost of HIV/AIDS treatment. Emphasizing movement may also lead to privileging some contexts while others are left unattended. After all, capital flows do not reach all corners of the world in equal measure. That the areas left outside of Appadurai’s analysis include large swaths of the African continent highlights the unfortunate correlation between neoliberal globalization, structural adjustment, and the spread of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS. In contrast, a focus on uneven development across space and time yields insights on how social inequality and illness are reproduced rather than mirroring the inequalities created by neoliberal globalization (Smith 1984; Harvey 2003). Considering how regional and national eddies form in contrast to the flows of globalization is necessary for understanding the dynamics of social inequality, health, and illness (Edelman and Haugerud 2005).

People, Pathogens, and Power

9

Anthropological analyses of the effects of HIV/AIDS treatment access have traced how transnational political and economic norms from the Global North create social effects on societies in the Global South. When making the connection between movement and context, these studies often presume that intermediary organizations, institutions, or interpersonal networks are a means of transmission rather than possible transformation. In short, they postulate that local actors and institutions are an extension of transnational movement and circulation. However, local organizations participating in such transnational circulations do not simply receive ideas, norms, and practices: they also shape them. Matamela’s experiences in Khayelitsha, where everyday material challenges weighed heavily in the lives of those who confronted the world’s largest HIV/AIDS epidemic, pointed to a different set of social dynamics than those imagined by Appadurai. How can contextual factors, such as those Matamela experienced, be brought into conversation with the movement and flows associated with globalization? Anna Tsing’s work (2000) offers a useful counterpoint here, as she is circumspect toward encompassing narratives of globalization and instead frames transnational dynamics as operating within locally situated sociopolitical processes, which she calls “projects.” Her ethnographically grounded approach considers how social processes operate at different levels in an increasingly interconnected world. While emphasizing the importance of context, Tsing’s concept of projects assumes a degree of continuity across levels, which may not always occur.4 Nevertheless, Tsing’s approach to locating transnational sociocultural process offers a useful tool for situating the sociopolitical dynamics of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic. Particularly important is the continued role of the state in Tsing’s conceptualization of context. Rather than assume a state is withering away, her approach analyzes transnational influences on historically particular sociocultural circuits, enabling one to see how state institutions have transformed during the contemporary phase of globalization (Hibou 2004). Following Tsing, this book reincorporates the state in order to better understand the extended campaign for treatment access, as the ANC’s AIDS-dissident faction utilized state health institutions to limit public sector access to HIV/AIDS treatment. Furthermore, as HIV/AIDS treatment access unfolded unevenly in South Africa, with some cities and provinces moving ahead of others in providing public sector care, I engaged in multi-sited ethnographic research. This allowed me to follow the different actors, organizations, and institutions influencing HIV/AIDS politics and see how HIV/AIDS treatment access was manifested at different institutional levels.

10

Introduction

HIV/AIDS, Hot Spots, and Political Process in South Africa The primary challenge I faced starting fieldwork was how to follow individual HIV/AIDS activists while also studying larger politics surrounding HIV/ AIDS. I learned very quickly that research participants’ everyday life activities did not neatly correspond to any discrete notion of politics or policy. The daily work of HIV/AIDS activists focused on addressing the difficulties faced by communities infected and affected by the epidemic, and access to treatment was one of many issues in their portfolio. Conversely, when I focused on the political controversy that surrounded a new national HIV/AIDS policy, as played out in newspapers and political speeches, it was often peripheral to the rich ethnographic material of everyday life. The methodological tension between studying HIV/AIDS politics and studying HIV/AIDS activism came to the forefront when selecting appropriate sites for fieldwork. How was I to choose the sites for data gathering that would be central to the politics of treatment access? Should I assume that policy would be created within state health institutions? What of the daily work of HIV/AIDS activists in the South African HIV/AIDS movement, such as Matamela? How could I analyze both sets of sociocultural dynamics within a single research project? I approached fieldwork with the intention of understanding how HIV/ AIDS politics operated across institutional levels. As a result, I analyzed political activities involving different organizations and activists at several physical sites in South Africa. This included conducting participant observation among a range of institutions, from district coordinating bodies and community-based organizations in townships to a national meeting of the South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) and an array of ethnographic encounters in between. Accompanying research participants from one site to another played an important role in data gathering, and I followed HIV/ AIDS activists to different meetings, conferences, protests, and policy consultations. I also kept pace with the political conflict over HIV/AIDS treatment access, following how people, organizations, and institutions were enmeshed in a broader sociopolitical process. The two frames of movement and context were inseparable; people moved, the political conflict shifted, and, all the while, communities infected and affected by the epidemic continued to suffer amid the material conditions produced by South African history. Multi-sited research initiatives offer a way to study sociocultural processes that accounts for movement, time, and space in the ethnographic analysis

People, Pathogens, and Power

11

of social life (Burawoy 1991; Marcus 1995; Lowe 1996; Ferguson and Gupta 1997; Fischer 1999a, 1999b; Wolf 2001). For my project, I linked together multiple field sites by “following” the movement of research participants. I built on George Marcus’s work, which outlines several permutations of following, including two that I employed: following the people and following the conflict.5 Anthropologists analyzing policy have adapted Marcus’s concepts to “follow the policy” and “study through” the policy process (Shore and Wright 1997). “Following the policy” involves analyzing the web of interpersonal, organization, institutional, and political relations that are engaged in the policy process (Shore and Wright 2011). “Studying through” traces those interpersonal connections in order to “illuminate how different organizational and everyday worlds are intertwined across time and space” (Wedel et al. 2005). While these approaches offer a way to study the policy-oriented conflict over HIV/AIDS treatment, they did not allow me to connect HIV/AIDS activists’ everyday activities to broader social processes, such as the development of national HIV/AIDS policy.6 A way to overcome the tension between movement and context grew out of my experiences moving alongside HIV/AIDS activists like Matamela. The pathways of different HIV/AIDS activists led me to intersections where HIV/AIDS treatment access was negotiated, and where I could combine the “following the policy” and “studying through” approaches. Field sites were determined by those who I followed: the HIV/AIDS activists, NGO representatives, and state administrators whose aggregated activities constituted South African HIV/AIDS politics. Following their pathways allowed me to identify field sites based on observed movements and connections rather than any predetermined notion of the field, policy, or the state. In short, it allowed me to identify particular sociospatial zones where the fight for treatment access was unfolding and the contours of local context were defined. Within these zones, HIV/AIDS activists and state administrators produced outcomes that affected HIV/AIDS treatment access. I conceptualize the interpersonal encounters I observed in this fieldwork as intersections of different pathways, laid out within a social field that is mediated by transnational influence.7 Following the pathways of people who had diverse institutional, organizational, and political affiliations enabled me to observe important variants of sociality within the larger field (Holston 1999). I observed a wide array of interactions and dynamics using this approach, with some involving small groups of people and others intense sociopolitical activity.

12

Introduction

I theorize these areas of concentrated sociopolitical activity related to the HIV/AIDS policy process as “hot spots.” In doing so, I build on the work of Hannah Brown and Ann Kelly (2014), who utilize the concept of hot spots to describe how infectious disease outbreaks grow out of a complex convergence of factors that create favorable conditions for transmission.8 In my study, localized political formations emerged at certain hot spots. Local actors and organizations transformed transnational forms of influence through their political activities, localizing the transnational dynamics of movement in a particular sociopolitical context (Powers 2017a). Where these hot spots emerged was dependent on the social and spatial concentration and interaction of actors, organizations, activities, and forms of influence. These hot spots produced “heat” via the concentration of political activity and the “friction” generated by the influence of transnational donors in the South African HIV/AIDS policy process (Tsing 2005). These areas where HIV/AIDS treatment access was negotiated were oriented around state health institutions but were not exclusive to them. Policy process is frequently conceptualized as unfolding within state institutions, which it quite often does. However, such a conceptualization may reify normative notions of the state and its institutions that may not be applicable in all societies, particularly those in the Global South, where state institutions and power dynamics were molded during the colonial era. Policy-making also happens along pathways, at intersections, and in hot spots. Over the past two decades, a growing focus on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) has given rise to a series of debates among anthropologists that focus on research methods and conceptual approaches to studying the state. Proliferating alongside the expansion of neoliberal globalization, NGOs have been characterized as a means of extending state power (Fisher 1997), mediators and translators for transnational flows of various kinds (Lewis and Mosse 2006), the glue that holds global neoliberalism together (Schuller 2009), and a productive site for examining the messy interface between state and society (Bernal and Grewal 2014). However, NGOs can be defined differentially depending on the situation, transforming their shape relative to context, audience, or particular goals (Sharma 2006), leading to their characterization as a “productively unstable” site from which to study the contemporary age (Lewis and Schuller 2017). As the South African HIV/AIDS movement was populated by NGOs of various kinds, the question of how best to study NGOs is a point that requires reflection. Indeed, as with the literature on “embedded” anthropology, research

People, Pathogens, and Power

13

focused on individual NGOs can restrict analyses to the boundaries of a particular organization and limit the capacity of the researcher to understand broader sociopolitical processes. While anthropologists have long called for research both within and through NGOs, there has been a marked tendency to limit the scope of analysis based on affiliation with a particular organization (Fisher 1997; McKay 2017; Reed 2018) In assessing this literature, David Lewis and Mark Schuller (2017) have called for a multi-sited, multilevel approach to studying the broader social dynamics within which NGOs are enveloped, a call that this book addresses through the methodology of pathways, intersections, and hot spots. Similar debates have emerged from anthropologists analyzing the expansion of global health interventions over the past two decades. NGOs have played a central role in the growth of transnational projects that address large-scale epidemics, and similar methodological and conceptual concerns have emerged among those engaging in “critical global health.” For example, João Biehl (2016) calls for “broad analyses of the power constellations, institutions, processes, and ideologies that impact the form and scope of disease and health processes” (130). Here, Biehl proposes a multilevel ethnographic analysis to address the complex social dynamics that global health interventions entail. Carrying out fieldwork across multiple levels and focusing on people’s experiences can produce different kinds of evidence, which can allow us to see the “the general, the structural, and the processual while maintaining an acute awareness of the inevitable incompleteness of our own accounts” (Biehl and Petryna 2014, 386). Building on these conceptual concerns, I carried out fieldwork across multiple field sites in South Africa between June 2007 and June 2008. My research concentrated on the cities of Cape Town and Johannesburg, although research participants led me to every health district in the Western Cape Province. Building on the methodology outlined above, I followed research participants across the South African landscape as they navigated the politics of HIV/AIDS treatment access. Here, I encountered what Paul Wenzler Geissler (2014) has coined the “archipelago of public health” as I observed how the scattering of NGOs and clinics across South African society simultaneously “projectified” the landscape of care and created new barriers to access based on interpersonal networks (Whyte et al. 2013). Research participants’ pathways converged at multiple points during the course of fieldwork, including at various regional meetings and local gatherings, some with more than two hundred participants and other quite small gatherings

14

Introduction

in communities infected and affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Analysis of these convergences shows that HIV/AIDS treatment access was negotiated not only in the Ministry of Health but in a wide variety of settings. I collected research data through participant observation of community meetings, subdistrict HIV/AIDS coordinating institutions, the Western Cape Provincial AIDS Council, and a national meeting of the SANAC civil society sectors. At these hot spots I identified and recruited research participants involved in the HIV/AIDS policy process. In total, I conducted fiftythree interviews with community members, HIV/AIDS activists, doctors and nurses working in the public health sector, NGO representatives, and state health officials. Interviewees were invited to participate in the research based on their involvement in the campaign for treatment access and were sampled based upon their involvement in the HIV/AIDS policy process; participants held a wide variety of organizational affiliations and diverse demographic backgrounds.9 Moving alongside those struggling for treatment access, I observed how the fight against the ANC’s AIDS-dissident faction unfolded and how the South African HIV/AIDS movement transformed the state from within to sustain the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS.

HIV/AIDS Activism and Social Change in South Africa Mobilizing communities infected and affected by the epidemic, the South African HIV/AIDS movement’s campaign for treatment access offers a means for understanding how a social movement—constituted by a broad alliance of activist groups, professional entities, scientific associations, NGOs, and community-based organizations—was able to successful engage with the state to increase treatment access. While supported by transnational donor capital and buttressed by international solidarity, the HIV/AIDS movement was made up of interpersonal and organizational networks based in South Africa and populated by South Africans. These networks can be traced back to the Mass Democratic Movement to end apartheid. The South African HIV/ AIDS movement was built upon this shared history and a common terrain of symbolic imagery. For example, HIV/AIDS activists adapted the songs and dances, known as the toyi toyi, that had been developed by the anti-apartheid movement to energize and unite people as they marched long distances (Robins 2004). Indeed, the HIV/AIDS movement built on these and other practices developed by the anti-apartheid movement to mobilize people during the campaign for treatment access.

People, Pathogens, and Power

15

The HIV/AIDS movement was also organized around political principles that emerged during—and were central to the unity of—the anti-apartheid movement, such as nonracialism, consultative decision-making, and broadbased alliance building. Thus, the notion that flows and NGOs from the Global North simply transport particular social, cultural, political, and economic tendencies to the Global South may not offer the most useful lens for understanding the South African HIV/AIDS movement. This book presents an in-depth analysis of the historical roots of South African HIV/AIDS activism, tracing its development alongside the anti-apartheid movement, to frame the campaign for treatment access as an extension of the struggle for black liberation in South Africa. Incorporating the impact of race and racism is particularly significant for analyses of South Africa, as it is a society whose history is deeply marked by racialized inequality. As Saul DuBow (1995) has outlined, the development of racial segregation in South Africa was associated with scientific racism during the colonial period and carried forward into the apartheid era. The impact of South Africa’s history of racial inequality was an active presence in the lives of those who participated in my research, and it also influenced their attempts to expand HIV/AIDS treatment access. Their experiences demonstrated resonances with anthropological analyses of race in other contexts, where the intersection of race, class, gender, and sexuality has been demonstrated to have significant public health effects (Harrison 2005; Mullings and Schulz 2006). Race has been shown to affect health outcomes through the impact of psychosocial stress on social and biological reproduction (Mullings and Wali 2001) and undermine subsistence strategies (Harrison 2007), particularly among female-headed households (Mullings 1995, 2005), leading to comparatively worse health outcomes for people of African descent in the contemporary United States (Dressler et al. 2005). That these patterns transcend national context and exhibit transnational tendencies has led some to characterize the contemporary context as “global apartheid,” while others have underscored the central role of race in forming the contours of neoliberal globalization (Harrison 2002; Thomas and Clarke 2013). Here, I build on anthropological approaches to studying race that contrast presumed sociocultural dynamics and observed sociocultural practices. Particularly significant for my analysis is Jackson’s (2001) approach, which juxtaposes “folk theories of race, class, and behavior” with the ways that people navigate a lived social context— Harlem, in Jackson’s work—that is circumscribed by the impact of race and racism. I adapt Jackson’s approach to address the disjuncture between how

16

Introduction

contemporary scholarship has characterized the South African state and the ways that HIV/AIDS activists experienced the power of race, and its relationship to the state, in their campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access. The HIV/AIDS movement offers a useful lens through which to understand how South African opposition to colonization, racial injustice, and social inequality continued to be manifested in the words and actions of those confronting the epidemic. Situating the South African HIV/AIDS movement within this broader historical arc yields important insights about the state, the impact of transnational influence, and the historically particular conditions that enabled the HIV/AIDS movement’s success in post-apartheid South Africa. The HIV/AIDS movement mobilized poor and working-class communities impacted by the epidemic and brought their voices and experiences into the state, transforming national HIV/AIDS policy and treatment access. It did so by expanding its representation in SANAC and creating space for people affected by the epidemic to have input into national HIV/AIDS policy. Indeed, the South African HIV/AIDS movement occupied the state to transform treatment access, and, in doing so, created a mechanism for amplifying the experiences of poor and working-class communities besieged by the epidemic. The HIV/AIDS movement laid claim to the socioeconomic rights that had been ensconced in the post-apartheid constitution—specifically the right to health—through their work within a state health institution. In doing so, HIV/AIDS activists changed the effects produced by the state on South African society. The South African HIV/AIDS movement’s success thus offers critical insight into anthropological theories of the state. Anthropological research on the state has emphasized the diverse forms through which state power manifests and produces effects. Contemporary analyses of the state focus on modes of knowledge through which people are disciplined and made productive, and how these modes of knowledge are disseminated, internalized, and reproduced (Foucault 1991; Scott 1998). These accounts tend to ascribe power to knowledge systems rather than people, tracing the ways that power and hierarchy are reproduced in a capillary manner. State power is thus understood through the ways that “state effects” are broadcasted, internalized, and regenerated, influencing identity formation and social reproduction (Mitchell 1991; Trouillot 2001). Other anthropological analyses of the state have emphasized how it holds power over life and death and can produce conditions of “bare life” for those deemed surplus to the formal political community (Agamben 1998, 2005;

People, Pathogens, and Power

17

Hansen and Stepputat 2006). There are important corollaries between a state of exception, where martial law unveils the roots of sovereign power in liberal democracies, and the way that state power was exercised in colonized societies, such as South Africa. Here, rather than exercise power by producing discourses that are subsequently internalized and used by people to structure their actions and reinforce existing power relations, the state engages in necropolitics, that is, it expresses power by producing death (Mbembe 2003). These analyses show that the exercise of power, such as by colonial commandement, can also uphold power relations, but in an inverse manner relative to Foucauldian conceptions of the state’s relationship to human vitality. In contrast, the campaign for treatment access shows that the state can be transformed to sustain human life based on the principle of social justice. While the campaign for treatment access was based on a rights-oriented approach to health, it was not predicated on creating a productive citizenry that reinforced existing power relations in South African society. Indeed, the vast majority of people living with HIV/AIDS were black and poor and had subsisted in conditions of “bare life” during colonization and apartheid. A close study of the HIV/AIDS movement shows that a state once designed to produce the conditions of bare life among part of its population, as in South Africa, can be reformed to sustain those very same lives. The South African HIV/AIDS movement underscores that people can have a decisive impact on the effects produced by state institutions. Its transformation of state institutions depended on people working within the state to expand treatment access. Members of the HIV/AIDS movement worked within government to overcome AIDS dissidence, change policy, and expand treatment availability. They cultivated alliances with members of the tripartite ruling coalition, which included the ANC, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), and the South African Communist Party (SACP). Rather than abstract economic forces or particular modes of knowledge, it was people—in long-standing interpersonal networks, with policy expertise, with biomedical knowledge—who expanded treatment access. By “occupying” the state, HIV/AIDS activists showed that state institutions have the capacity to amplify alternative visions of society that challenge existing power dynamics. The South African HIV/AIDS movement highlights that the state can produce a range of vastly different social effects; which ones come into being depends on which groups of people set policy and control government institutions. Indeed, analyzing the role of people in the state shows how local bureaucrats can blur the line between state and society while also

18

Introduction

making decisions that can define the life possibilities for those dependent on state support (Gupta 1995, 2012). One of the most important effects that a state can have is to sustain or end the lives of people (Agamben 1998; Mbembe 2001). The campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access in South Africa shows that the politics of life and death can be altered based on sustained activism. Activists and people living with HIV/AIDS enabled a plurality of experiences to be incorporated into state policy, changing state effects. In the twenty-first century, notable US social movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter have eschewed formal political demands and state-oriented strategies for securing social change, instead focusing on creating nonhierarchical social movements that enact the political dynamics its members want to see in society, what some scholars have called prefiguration (Maeckelbergh 2011; Yates 2015). In doing so, activists have built upon social movement practices developed elsewhere, such as Argentina, where “horizontal” forms of political association developed in the aftermath of financial crisis (Sitrin 2012a). In contradistinction to these examples, the South African HIV/AIDS movement enacted a formal political approach, including using legal activism to leverage the right to health and occupying the state to sustain the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS. The case of the campaign for treatment access is an important example that can broaden our understanding of why some social movements may succeed in changing a society while others fall short. The political principles of the anti-apartheid movement and the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic were elements that could be used to build a common platform to challenge government intransigence and expand access to treatment. These political principles united the members of the HIV/AIDS movement despite their different ethnic backgrounds, class positions, sexual orientations, and professions. People shared their concerns, developed organizations, put their thoughts into action, and, eventually, occupied the state and transformed treatment access in South Africa.

An Outline of the Book This Introduction outlines the book’s approach to analyzing the politics of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic in relation to academic debates on HIV/AIDS, transnationalism, social movements, the state, and multi-sited research. The two subsequent chapters offer a historical overview of South

People, Pathogens, and Power

19

African society and the politics of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic, respectively. The ethnographic section of the book follows, with three grounded analyses of HIV/AIDS politics at the national, provincial, and local levels. The book concludes by relating the success of the South African HIV/ AIDS movement to debates on transnationalism, the state, and social change. Chapter 1 takes the reader through the history of contact, colonization, and apartheid, discussing the divergent sociopolitical trajectories that were subsumed under unified white rule following the South African War (1899– 1902). The institutionalization of indirect rule, segregation, and social, economic, and political inequality were the bitter fruits of white settler alliances in South Africa. Analyzing the recurrent forms of self-governance that emerged intermittently across the twentieth century, I demonstrate that the apartheid project never fully succeeded in its mission of “ordering” in South Africa. Notably, attempts at autonomous self-governance in black urban areas led to the development of political ideals within the anti-apartheid movement, such as nonracialism, which subsequently influenced HIV/AIDS activism. Chapter 2 presents a historical analysis of South African HIV/AIDS activism and the political struggle over access to treatment. Using biographical notes, interview excerpts, and ethnographic description, I ground historical events in the lives of those who led the campaign for treatment access. With a focus on interpersonal networks, I analyze how HIV/AIDS activism emerged from several groups involved in the anti-apartheid struggle: the human rights movement, the gay rights movement, the primary care movement, and the left. The first wave of South African HIV/AIDS activism (1982–1998) contributed to the development of the post-apartheid constitution, led the campaign for a rights-based approach to HIV/AIDS, and established organizations that cultivated second-wave HIV/AIDS activists. Indeed, the second wave of South African HIV/AIDS activism (1998–present) coalesced in response to the growth of the epidemic, government inaction to stem its tide, and the emergence of the ANC’s AIDS-dissident faction. This chapter shows that both the ANC’s AIDS-dissident faction and the South African HIV/AIDS movement depended on state institutions to achieve their goals. While activists initially relied on judicial institutions to transform national policy, the ANC’s dissident faction managed to limit the availability of treatment by controlling state health institutions. In order to achieve the goal of treatment access, the South African HIV/AIDS movement had to change the state from within. Chapter 3 tracks second-wave HIV/AIDS activists as they worked within national health institutions and developed new national policy. At the heart

20

Introduction

of this ethnographic chapter is an account of a SANAC national civil society meeting where new national policy recommendations were developed for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV. The development of those recommendations was enabled by the influence of transnational biomedical norms and HIV/AIDS activists working in communities. While the recommendations largely reflected guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO), simply noting similarities between transnational and national policy processes does not explain how such an outcome came about. The guidelines from the WHO became intelligible only through accounts offered by HIV/AIDS activists on the everyday challenges faced in clinics and communities across the country. Thus, the campaign for treatment access at the national level reveals how policy development grew out of the experiences of community-based HIV/AIDS activists in tandem with biomedical experts rather than simply reflecting transnational norms. In Chapter 4, my ethnographic analysis focuses on the campaign in South Africa’s Western Cape Province, describing a series of policy consultations carried out in each of the province’s six health districts. Providing evidence from participant observation and interviews, I show how relationships between activists, NGOs, and state health administrators produced unpredictable outcomes in the campaign for treatment access at the provincial level. The provincial meetings had been organized in response to a new national policy mandating that 80 percent of people in need should be provided with public sector treatment. However, the desire to secure transnational donor capital undermined provincial efforts. In the end, these consultations did not seek to expand HIV/AIDS treatment access but instead gathered data for funding applications to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund). This redirection of national policy at the provincial level indicates that different actors and organizations at the subnational level have the capability to transform policy outcomes and inform the impact of transnational donor capital. Chapter 5 focuses on the campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access in the township of Khayelitsha. The chapter tracks the extension of HIV/AIDS activism from Site B Day Hospital in Khayelitsha, where health-related protests and the political campaign for access to treatment were focused, to other areas of the township, where AIDS dissidence limited community education and outreach programs. The pattern that emerged was activists’ isolation from local political venues such as street-level committees and community halls. In Khayelitsha, a local branch of the South African National Civics Organization

People, Pathogens, and Power

21

(SANCO), an organization that played a significant role in the anti-apartheid movement, closed local political structures to discussions of HIV/AIDS and limited the oversight of local HIV/AIDS coordinating institutions. Indeed, SANCO played a central role in piloting an unproven vitamin-based HIV/ AIDS treatment, which led to the premature deaths of people living with HIV/ AIDS in Khayelitsha. The analysis of local-level HIV/AIDS politics highlights how national AIDS dissidence was enacted at the local level and the efforts of community-based HIV/AIDS activists to counteract these initiatives. In the concluding chapter, I return to theoretical debates reviewed in the Introduction, situating conceptual insights gleaned from the ethnography within a discussion on transnationalism, social movements, and the state. The South African HIV/AIDS movement was built on the political principles of African liberation to transform the public health response to the epidemic and sustain the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS. My analysis shows that this connection was based on the interpersonal networks that connect waves of South African HIV/AIDS activism. These personal ties have served as conduits for the transmission of social movement knowledge and practices across time. Rather than transnational biomedical norms simply being reflected, updated HIV/AIDS policy guidelines were created because of the efforts of the HIV/AIDS movement, including people living with HIV/AIDS. Provincial HIV/AIDS policy dynamics highlight the influence of local actors and organizations, showing how transnational donor capital was redirected to serve state interests and NGOs that were dependent on government financial support. The trajectory of HIV/AIDS policy at both the national and provincial levels was determined by local people and organizations rather than abstract transnational forces. Much contemporary analysis has focused on the influence of experts in producing policy and their reliance on technical criteria rather than the needs of everyday people. The campaign for treatment access shows how the HIV/ AIDS movement created space for poor and working-class South Africans to influence state policy and alter national health institutions. This was contingent upon members of the HIV/AIDS movement working within the state, where they were able to change how institutions operated and their effects on South African society. In sum, the book underscores that it is people who determine how state effects are produced and that those who control the state can fundamentally alter state effects. What are the long-term effects of the campaign for treatment access in light of the continued impact of HIV/AIDS on South African society? In the

22

Introduction

Afterword, I describe how, despite access to treatment, the epidemic has continued to grow. Socioeconomic conditions continue to produce poverty and illness among South Africa’s black majority, and material privation and survival strategies continue to foment the spread of HIV/AIDS. While the campaign for treatment access successfully met its goal, the ongoing epidemic highlights the limits of a right-based social movement. That the relative success of the HIV/AIDS movement has not been enough to stop the expansion of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic underscores that transforming the social determinants of health may require a different approach to social change.

CHAPTER 1

Contact, Colonization, and Apartheid South African Social Formations in Historical Perspective

The South African HIV/AIDS epidemic developed within a set of historically particular political, economic, and sociocultural conditions that shaped the extended campaign for HIV/AIDS treatment access. A historical analysis of the African continent’s southernmost society shows how the contours of contemporary South Africa emerged out of its past. Uneven development and unequal health outcomes were produced by the interaction of South African social groups, or social formations, over five centuries. Starting with a review of indigenous political formations in Southern Africa, this chapter takes the reader through the history of contact, colonization, and apartheid, paying particular attention to the role of institutions in producing unequal health outcomes along racial lines. The colonial period in South Africa was marked by contact and conflict between European settler states and indigenous African political formations, which influenced the subsequent development of South African society. From the slave economy of the early Dutch settlements to the British Empire’s extension of state administration, settler societies engaged with African political formations in ways that extended their interests while expropriating land and resources from indigenous peoples, producing negative health outcomes along the way. Alongside colonial states, the development of rural missions provided health services and education to indigenous South Africans while disseminating Christianity. Indeed, the diffusion of Western religion and biomedical practices across the South African hinterland occurred alongside expropriation and enslavement.1

24

Chapter 1

As British and Afrikaner polities united following the South African War, social, political, and economic dynamics that had emerged during the colonial era were set into law. The institutionalization of indirect rule, segregation, and land expropriation was the bitter fruit of this white settler alliance in South Africa. The state produced by unified white rule was based on programs to address white poverty, which reinforced racial inequality. The establishment of large parastatal corporations, social welfare provisions, and a bifurcated wage and labor system created a Keynesian welfare state, but it was one that supported the country’s white population. The period of unified white rule set into motion institutional precedents that expanded racial stratification, formalized land expropriation, and limited the scope of political, economic, and cultural autonomy for black South Africans. Building on earlier political, economic, and institutional dynamics, the apartheid era led to intensified racial segregation, state violence toward black South Africans, and “separate development.” However, those directing apartheid never completed their aim of “ordering” black urban and rural spaces in South Africa (Posel 1991). While traditional leaders exerting political authority in rural Bantustans may have functioned as “decentralized despots,” they also highlighted the limited reach of the South African state (Mamdani 1996). Recurrent forms of self-governance emerged intermittently in black urban areas: the history of the Soweto and Alexandra townships show how a lack of legitimate and representative political institutions led to political self-organization. The anti-apartheid movement also had urban roots, considering the complicity of rural traditional leaders with the apartheid state. Anti-apartheid activists built on the political principles developed by black urban social formations that served as the foundation for the Mass Democratic Movement in the 1980s that aimed to end apartheid and, subsequently, the South African HIV/AIDS movement. Tracing the political principles of the anti-apartheid movement to the HIV/AIDS movement, I take a multipolar approach to South African history, showing how the interaction between linked but distinct social formations produced unequal health effects that adversely affected nonwhite populations. But in order to discuss the historical context for the emergence of the world’s largest HIV/AIDS epidemic, I first outline how particular populations came to embody inequality. In addition, understanding how the HIV/AIDS movement transformed the state to sustain the lives of historically marginalized people entails understanding the roots and principles of political resistance across South African history.

Contact, Colonization, and Apartheid

25