The Politics of Sociability: Freemasonry and German Civil Society, 1840-1918

665 54 4MB

English Pages [250]

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

Page viii → Page ix →

Preface This book grew out of my dissertation, completed at the University of Bielefeld in 1999 and published by Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht in 2000. The German edition was received by and large as a contribution to the expanding literature on nineteenth-century bourgeois culture. My primary motivation in writing this book, however, was actually somewhat different. It was the unexpected renewal in the 1990s of a preoccupation with notions like civility, civil society, a cosmopolitan ethos, and moral justifications for war that spurred my interest in writing on nineteenth-century Freemasonry. I wanted to explore the unintended political consequences of Enlightenment ideas and practices in an age characterized by the advent of nationalism, anti-Semitism, and social discord. The self-image of Freemasons as civilizing agents, acting in good faith to promote the idea of universal brotherhood, was contradicted not only by their sense of exclusivity. For it is my contention that Freemasons also unintentionally exacerbated nineteenth-century political conflicts—for example, between liberals and Catholics, or the Germans and the French—by what I call moral universalism: the grounding of political arguments on universalist pretensions that obscure the legitimate norms and interests of their contenders. The book appeared simultaneously with other critical accounts of the actual workings of civil society in nineteenth-century Europe, notably by Frank Trentmann and Philip Nord, both of whom shared their insights with me. However, this edition includes studies published after 2000 only in those cases where the German edition referred to earlier versions of the argument by the same author, for example, in an unpublished paper. I do discuss much of the more recent literature in what has now become a growing concern among historians with the cultural context and content of the political in my book Civil Society, 1750–1914, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2006. Page x → I wish to thank the editors of this series, in particular Geoff Eley, and three anonymous readers for their valuable suggestions. I did, for example, remove most of the statistics, which, however, can be consulted in the German edition. I also benefited from comments by colleagues, particularly at the Johns Hopkins University, where I submitted my first paper on the subject as an MA thesis, and Bielefeld, where I had the privilege of working with Hans-Ulrich Wehler and Reinhart Koselleck, and conversing with Svenja Goltermann, Christian Geulen, and Till van Rahden. In the end, of course, I alone assume responsibility for any errors in statements of fact or argument. The translation of a book always takes more time than expected, and I thank my editors at the University of Michigan Press, initially Chris Collins and later Jim Reische, for their patience and support. The Stiftung zur FГ¶rderung der Masonischen Forschung kindly sponsored the translation of a sample chapter. Finally, I owe my greatest debt to Tom Lampert, a meticulous translator and keen writer, for working so closely with me on a book that is very much concerned with language. Parts of this book draw on materials that I have published earlier: passages in chapters 2 and 3 were included in “Brothers or Strangers? Jews and Freemasons in Nineteenth-Century Germany,” German History 18 (2000): 143–61; chapter 5 is essentially the same essay that was published as “Civility, Male Friendship, and Masonic Sociability in Nineteenth-Century Germany,” Gender and History 13 (2001): 224–48; the argument of chapter 8 was first presented in The Mechanics of Internationalism: Culture, Society, and Politics from the 1840s to World War I, ed. Martin H. Geyer and Johannes Paulmann (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). Cambridge, Mass., May 2006

Page 1 →

Introduction Bowling Alone is the title of a best-selling study published in 2000 by the American political scientist Robert Putnam. The title identifies what Putnam regards as one symptom of an alarming development in the United States: Although more Americans than ever go bowling, the percentage of those who do so as part of a club or organized group has decreased significantly. Putnam points out that membership in such diverse organizations as the Boy Scouts, the Red Cross, and Masonic lodges has sunk dramatically over the past thirty years, as has active citizen participation in local community affairs. Only national organizations that merely represent interests and do not cultivate any common social life, such as the American Association of Retired Persons, have flourished.1 Yet what is so alarming, we might ask, about the fact that Americans today do not engage in established forms of sociability, that they bowl or watch television alone, and that they are content to have their interests represented by organizations they know only through letters and e-mails? At stake, according to Putnam, is the very foundation of American civil society and American democracy.2 Drawing on the political theory of Alexis de Tocqueville, Putnam argues that civil society is founded neither on the readiness of individuals to obey their government nor on the calculated pursuit of economic self-interest, but on civic virtue.3 Without civic virtue, there is no civil society—that is the fundamental premise of this political theory—and civic virtue unfolds only through the interaction of citizens with one another, through their sociability. As Tocqueville wrote in 1840, “Sentiments and ideas renew themselves, the heart is enlarged, and the human mind is developed only by the reciprocal action of men upon each other.” According to Tocqueville, this reciprocity, which was subject to rigid rules and regulations in corporative society, has to be produced Page 2 →artificially in civil society. “And this,” he argued, “is what associations alone can do.”4 There is, in other words, a profound connection between the “moral improvement” of individuals and the “civility” of the society they constitute. “Among the laws that rule human societies,” Tocqueville continued, “is one that seems more precise and clearer than all others. In order that men remain civilized or become so, the art of association must be developed and perfected among them in the same ratio as equality of conditions increases.”5 Conversely—and both Putnam and Tocqueville share this concern—when the ties that bind individuals together and guarantee their virtue begin to loosen, the political foundations of civil society threaten to erode.6 The less citizens practice the “art of association,” the more “uncivil” society becomes. Tocqueville employed an apocalyptic image to illustrate what a democratic society would look like when it no longer secured its political foundations through the sociability of its citizens: “I see an innumerable crowd of like and equal men who resolve on themselves without repose, procuring the small and vulgar pleasures with which they fill their souls. Each of them, withdrawn and apart, is like a stranger to the destiny of all the others: his children and his particular friends form the whole human species for him; as for dwelling with his fellow citizens, he is beside them, but he does not see them; he touches them and does not feel them; he exists only in himself and for himself alone, and if a family still remains for him, one can at least say that he no longer has a native country. Above these an immense tutelary power is elevated, which alone takes charge of assuring their enjoyments and watching over their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, far seeing, and mild. It would resemble paternal power if, like that, it had for its object to prepare men for manhood; but on the contrary, it seeks only to keep them fixed irrevocably in childhood . . .”7 Putnam may have had this scenario in mind when he described with such alarm the isolation of Americans even when bowling. We could reformulate Tocque-ville’s argument as follows: In civil society, an apparently apolitical sociability has a political dimension. “The new political science,” which Tocqueville wanted to establish as the “basic science of civil society,” was supposed to be concerned primarily with the “art of association,” that is, with sociability. For Tocqueville, the progress of all other sciences was dependent on this one basic science.8 In the debates about German civil society following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Tocqueville’s theses about civic virtue, sociability, and Page 3 →democracy have admittedly played no role whatsoever, although the

German neologism Zivilgesellschaft (literally, civil society) has stood at the center of these debates. There are numerous reasons for this, and the very use of the word Zivilgesellschaft points to one key issue: Germans employed this newly invented term rather than established ones such as bГјrgerliche Gesellschaft or BГјrgergesellschaft in order to emphasize the ostensible novelty of this contemporary political vision. The German neologism Zivilgesellschaft suggests that the English term civil society and its historical traditions have no equivalent in Germany. By dispensing with the German term BГјrger and the “bourgeois” historical connotations that continue to be associated with it, it was easier to cleanse this political vision of past ruptures and ambiguities. “Civil society,” one might suppose, has no past whatsoever in Germany. It has only a future.Introduction Like the term BГјrger, the German word Tugend (virtue) has had similarly pejorative connotations throughout the twentieth century. Although virtue was initially regarded as a central element of the Enlightenment in both Germany and France, the term experienced a dramatic devaluation in Germany beginning in the late nineteenth century through the discourse of the political Right. Leftist discourse only exacerbated this development after 1945. The discussion of specifically German “secondary virtues” that ostensibly contributed to the rise of National Socialism also helped to discredit the concept of virtue in Germany; in Herfried MГјnkler’s words, “Virtue became secondary.”9 Thus contemporary German theorists of civil society or Zivilgesellschaft regard any appeal to an intimate connection between civic virtue and civil society—a standard position today not only among communitarians in the United States—as conservative and antiquated. From JГјrgen Habermas to Ulrich Beck, German theorists of civil society simply disregard the possibility that civil society might require, in addition to free trade and liberal constitutions, a third pillar—the morality of its citizens, who acquire their virtue through interactions with each other, that is, through the “art of association.” As strange as this connection between civic virtue and civil society might appear to German theorists of civil society today, it was in fact quite familiar to the “practitioners” of civil society during the “long nineteenth century.”10 That is the first premise of this study. With the exception of the United States, there was hardly another society in the nineteenth century that was as “sociable” as Germany. Contemporaries in Germany spoke of the “rage for associations,” initially in the transition from corporative society to civil society from the end of the eighteenth century to the Revolution Page 4 →of 1848–49 and then in an even more pronounced form during the era of emergent civil society from the 1860s up to the First World War.11 This sociability of citizens was supposed to raise their “civility,” or in nineteenth-century parlance, “their humanity,” “their morals,” and their Bildung. “The exercise of virtue” and “civic association” appeared to be intimately connected.12 Through their participation in associations, joiners raised an explicitly moral-political claim: “Civilizing” oneself through interaction with others was supposed to produce a civic sense (BГјrgersinn) and, beyond this, a cosmopolitan sense (WeltbГјrgersinn). The fact that participation in the sociable circles of a city was tied to particular restrictive criteria such as education, independence, and masculinity indicates the double-edged nature of this civility. Citizens of the nineteenth century asserted a value system that claimed to be valid for all humans, and yet they identified these values initially only with people who already satisfied these social and moral demands.13 The German term BГјrger, which encompasses both the legal-political connotations of the “citoyen” and the social-moral connotations of the “bourgeois,” indicates this double-edged nature. The tension between universal claims and social-moral exclusivity was part and parcel of this vision of an intimate connection between civic virtue and civil society in the nineteenth century. That is the second premise of this study.14 The “art of association” was not only supposed to produce better citizens and men. This art itself was supposed to be accessible only to those deemed capable of civility. From this sense of moral capacity, German BГјrger derived their claim to lead local communities, to lead the nation, and, in a figurative sense, to lead humanity as a whole. In this regard as well, sociability was political. What effect did this belief in their own civility have on the various political and social conflicts of the nineteenth century? The present study attempts to demonstrate that the connection between sociability and political civility was not as unambiguous as Tocqueville and other liberal thinkers of the time believed. As recent comparative studies have shown, one of the most overriding passions of civic associations in nineteenth-century Europe was excluding and disciplining those who

were not regarded as “civilized.”15 The third premise of this study is that over the course of the nineteenth century the tension between universal claims and social-moral exclusivity increased as civil society developed, as other social groups adopted “civility” as a cultural model. At the end of the nineteenth century, German BГјrger perceived a threat in this diffusion: The intimate connectionPage 5 → between society and civility—and indeed virtue itself—appeared to be in jeopardy. This in turn was understood as threatening the moral foundations of the political vision of civil society. The desire for the “moral improvement” of individuals, of local civil society, of the nation, and ultimately of humanity as a whole has always produced its “other,” which then threatened this political vision.16 Paradoxically, it is precisely this “other” that drives forward the desire to “civilize” completely and yet at the same time prevents this desire from ever being fulfilled. The “other” is supposed to be integrated, “civilized,” to become part of “general humanity,” and yet one’s own superior civility can only be asserted as long as this opposite or “other” exists—in oneself, in local civil society, in the nation, and in humanity as a whole.Introduction Masonic lodges were both the paragon of civic associations and one of its oldest forms. The lodges were a form of sociability peculiar to civil society—indeed were a model of civil society: “Freemasonry is nothing arbitrary, nothing superfluous,” Lessing wrote in Ernst und Falk in 1779. “Rather it is something necessary, which is grounded in the nature of man and of civil society.”17 As an institution, the lodges helped to ensure that the ideas and practices of the eighteenth century survived, albeit with modifications, and remained socially effective up into the early twentieth century. Through the example of Masonic lodges, we can analyze the belief in the connection between civic morality and civil society throughout the course of the nineteenth century. To date scholars have largely ignored the history of Masonic lodges in Europe in the nineteenth century.18 Occasionally historians have even expressed surprise that lodges existed during this period at all. After all, lodges arose during the Enlightenment, as a special part of the emerging public sphere, as a new form of sociability, in which bourgeois and aristocratic elites established a common space for communication on the eve of the French Revolution. The lodges sought to develop a form of sociability beyond existing corporative, religious, and political limitations, beyond the old political order as well as emergent civil society, a space in which the “parity of the purely human” (JГјrgen Habermas) would overcome the particular interests of individuals and encourage Bildung in the sense of a moral improvement of one’s own individuality.19 “Quite contrary to its purpose,” as Lessing noted, civil society creates social, religious, and political divisions. “It cannot, ” he continued, “unite men without parting them; it cannot part them without establishing gulfs among them, without drawing partition-walls through them.” “If a German meets a Frenchman at Page 6 →present, or a Frenchman an Englishman, or vice versa, then it is no longer a mere man, who by virtue of their identical nature will be attracted one to the other, but a particular kind of man meets a particular kind of man,” both of whom are conscious of their differences. For Lessing then, the central purpose of Freemasonry was to “draw together as narrow as possible those divisions through which men become so strange to each other.”20 Lessing anticipated Tocqueville’s arguments here and pointed to the political implications of enlightened sociability. More than any other form of sociability in the eighteenth century, Masonic lodges recast enlightened ideas as rituals and social practices that aimed at “civilizing” lodge brothers. In this figurative sense, Freemasons were “living the Enlightenment,” to use Margaret Jacob’s apt phrase; the lodges were “civil and hence political” in the sense that they served as microcosms of emerging civil society.21 Even if it is mistaken to regard Freemasons as the secret force behind the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror (they were, in fact, among its first victims), the pre-political moral language and the social practices of the lodges did possess a political dimension. It is precisely this dimension of Freemasonry that interested both Reinhart Koselleck in his study of the “pathogenesis” of modernity and JГјrgen Habermas in his book on the public sphere.22 The theoretical premises of these seminal studies as well as the fact that both focus on early modern ideas and practices but implicitly trace their effects into the twentieth century raise the question of the fate of enlightened sociability and its moral language in the long nineteenth century.

The present study is divided into three parts, each of which employs a different but complementary approach to the history of Masonic lodges. While a concise history of German Freemasonry in the nineteenth century (particularly from a comparative perspective) would be a worthwhile undertaking, here the example of the lodges is used to engage in a critical examination of the questions and premises outlined previously. The first part of the book traces the changing significance of Masonic lodges within two local communities throughout the course of the long nineteenth century. The second part investigates language and social practices within the lodges more closely, both of which were supposed to foster “improvement of the self” and thus lead to civic virtue. The third part of the book examines lodge speeches, analyzing the transformation of a moral language into a political, patriotic language in particular during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the subsequent rapprochements between French and German Freemasons prior to 1914. The book concludes with a brief review Page 7 →of the tumultuous history of Freemasonry during the “new Thirty Years War” (Raymond Aron) beginning in 1914.Introduction The first part of the book investigates the changing significance of the lodges for civil society in Germany between the VormГ¤rz period and the First World War. It also examines their significance in regard to the state, the monarchy, and the church. Almost all studies focusing on the connection between the emergence of the modern self and the flourishing of associations have concentrated on the so-called Sattelzeit between 1750 and 1850.23 It is usually assumed that associations were less significant for later time periods, although the number and the size of associations in Germany increased dramatically in the 1860s and 1870s, and associations ultimately came to permeate all domains of society in imperial Germany.24 In order to investigate both the constancy and change in Masonic sociability, this study will focus primarily on the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.25 Moreover, in this and other parts of the book, German Freemasons are compared with their French and American brethren in the nineteenth century. French Freemasons are considered political pioneers and social pillars of the Third Republic, while American lodges are generally regarded as the paragon for the numerous associations and secret societies that formed the backbone of American democracy after the Civil War.26 It is also important to determine who had access to Masonic sociability in a particular city and who was excluded, as well as to examine the different criteria—class, gender, religion, and race—used to determine this inclusion or exclusion. I am interested, in other words, in the boundaries lodges drew by means of their moral-political imperatives and in the language they employed to justify these boundaries. In terms of social history, I attempt to determine the social profile and the age groups, as well as the religious and political affiliations of lodge members between 1840 and 1914. Conversely, I also use existing collections of unsuccessful applications for lodge membership and the (often quite protracted) negotiations of individual applications to determine who was not regarded as “respectable” and the justifications for such decisions. Here I pay particular attention to the way in language was used to construct identity and distinction. Even more than the social and gender boundaries (the latter are considered in detail in part 2), religious boundaries blatantly contradicted the humanist language of Freemasonry. Following a recent trend among historians, this study investigates the fundamental significance of tensions between Catholics, Protestants, and Jews in nineteenth-century German Page 8 →civil society.27 The conflict with Catholicism was particularly significant in defining the self-image of the lodges—a conflict that reached its climax during the Kulturkampf, although it existed throughout the entire nineteenth century and into the First World War. Moreover, the question of the inclusion or exclusion of Jews had, since the early 1840s, divided lodges into a liberal camp (e.g., in large trading cities such as Leipzig, Hamburg, or Frankfurt) and a conservative camp (in particular in Prussia, with Berlin and Breslau as its centers). In order to compare these two camps, the present study focuses on Masonic lodges in Leipzig and Breslau.28 It also provides comparative results on a regional level (Prussia and Saxony) and a national one (Germany, France, and the United States). In the second part of the book, the perspective shifts to the inner workings of lodge life. The focus here is on the language and social practices within the lodges, both of which were supposed to help realize the idea of moral improvement.29 The lodges were supposed to be “educational institutions for the humanity of men,” as Johann Caspar Bluntschli explained in his liberal StaatswГ¶rterbuch, schools of civic virtue.30 Even in the

nineteenth century—the era of the public sphere—such an education appeared possible only in confined social spaces, which in the case of the lodges continued to be veiled in secrecy. Such social spaces were removed from civil society and its everyday political life. However, it would be a mistake to regard this withdrawal to “moral introspection” as apolitical escapism. Rather, in these spaces lodge brothers were supposed to learn to govern their individual selves in order to be able to govern society as a whole. In the first chapter of this part, the example of Masonry is used to illuminate the nineteenth-century belief in the connection between civic virtue and sociability. The next chapter investigates in depth the complicated rules and rituals of the lodges, which were quite literally supposed to maintain the brotherhood of men. Here the focus is not only on sociabilitГ© in general31 but also on what might be called the practices of the self. These rituals enabled Masonic ideas about moral and political order to be experienced on a physical level. The rituals were supposed to “civilize” members until virtue became, in Georg Simmel’s words, “a constitution governing from within.”32 The cult of fraternity was a singularly masculine cult. The second chapter of part 2 also examines the extent to which this idea of civilizing the self, of civilizing society, and ultimately of civilizing humanity was constructed in gendered terms. The following chapter addresses a related issue: Does the idea of civic virtue include a specific form of religiosity, a Page 9 →civil religion that is distinguished from the alleged “feminization of religion” in the nineteenth century? What did the civil religion typical of the lodges look like? What made it attractive even in the final third of the nineteenth century, despite the growing predominance of science and the decline in church attendance at the time? Why did the elevated BГјrgertum assembled in Masonic lodges perceive the crisis of modern society prior to 1914 as a moral crisis? Does this moral critique of modernity testify to a “deficit of civility” or to a reformulation of the BГјrgertum’s claims to lead and to reform the society of imperial Germany?Introduction The third part of the book investigates the moral-political language of Freemasonry, focusing especially on speeches by Freemasons within the lodges. In the nineteenth century, the improvement of the self, of civil society and the nation, and ultimately of humanity formed an inseparable triad. In 1840, Tocqueville provided the following explanation for the fact that “American writers and orators are often bombastic”: “In democratic societies each citizen is habitually occupied in contemplating a very small object, which is himself. If he comes to raise his eyes higher, he then perceives only the immense image of society or the still greater figure of the human race. He has only very particular and very clear ideas, or very general and very vague notions; the intermediate space is empty.”33 Here Tocqueville observes how the concern with improvements of the self is closely tied to vague expectations about society, the nation, or humanity. In the first chapter of part 3, the example of Masonic lodges is used to outline the semantic connection between these various levels. The following chapter investigates in greater detail the political consequences of the lodges’ humanist and cosmopolitan self-understanding during the era of nation-states and wars. The central focus here is the tension between German and French Freemasons during the era between the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War. The mixing of nationalist and universalist rhetoric in lodge speeches suggests an ambiguity similar to the one outlined previously in regard to civic virtue and civil society. The utopia of an idealized unity—of the self, of civil society or the nation, and ultimately of humanity—has always produced its “other,” which appears to threaten the welfare of that unity, and this in turn allows that unity to be demarcated and reasserted more strongly.34 The fact that Freemasons in both Germany and France attributed a universal mission to their respective nations even after the outbreak of the First World War does not so much represent a break with the enlightened-liberal tradition as reveal an ambivalence within that tradition. As I argue Page 10 →in the conclusion, the lodges were by no means an exception in this regard. The humanist justification of war in the name of the German or, conversely, the French nation (as well as the intensification of national enmity tied to this) ultimately led to a disavowal of the concepts of civilization and humanity in both countries after the First World War.35 An intrinsic connection between Freemasonry and civil society has existed since the eighteenth century. This is evident in the difficulties lodges experienced in the autocratic Habsburg and czarist empires in the nineteenth century as well in the ban on lodges in the Soviet Union in 1918, in Italy in 1925, and in Germany ten years later.

The persecution of Masonic lodges in Nazi Germany and in the nations occupied by the Germans and their allies had the paradoxical result that an almost complete collection of Masonic documents in Germany survived the Second World War. Today most of these documents are located either in the State Archive in Berlin- Dahlem, in a branch of the University of Poznan’s library in the Ciazen Castle, or in the Central State Archive in Moscow.36 The history of this collection of documents is itself part of the history of Masonic lodges in Germany. Over the course of the nineteenth century and in particular after the First World War, the terms bourgeois, liberal, and Jewish were reduced to stereotypes, which congealed into a distorted image of Freemasonry that haunted the German (and European) political imagination between the two world wars—an image by no means limited to right-wing circles. Between 1933 and 1935, the Nazis confiscated all materials held in local lodge archives. The extensive files that every lodge had kept since its founding, extending in some cases back into the early eighteenth century, were transferred to the central Gestapo archive in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. After 1935, a division in the Reich Security Main Office was established to evaluate the personal files of the lodges and to conduct a series of pseudo-scientific studies that were supposed to prove a Jewish-Masonic world conspiracy.37 During the bombing of Berlin, these files were moved to two castles in Silesia, where the Red Army subsequently assumed control of them. The pamphlets and journals remained in the library of the University of Poznan, while the lodge files were transferred to Moscow—Stalin, too, was obsessed with the idea of a Jewish-Masonic world conspiracy. After Stalin’s death, a portion of the lodge files were transferred to the German Democratic Republic, where they were not accessible to the public; the rest of the files remained in Moscow. They have only recently become available to scholars.Introduction Page 11 →The present study is based primarily on three different groups of documents. The first of these are the government files concerning the surveillance of Masonic lodges, in particular by the Prussian and Saxon Departments of the Interior. Since the late eighteenth century, Freemasonry in Prussia and Saxony—in contrast, for example, to Bavaria or the Habsburg empire—was tolerated by the state but kept under surveillance. These files demonstrate how tense relations were between the state, the monarchy, and the church, on the one hand, and the lodges, on the other. The lodge files constitute the second and largest group of documents. The present study was able to evaluate systematically only the documents of the Leipzig and Breslau lodges and, in part, those of the Berlin and Dresden grand lodges. These files encompass statutes and laws, minutes of lodge meetings, unpublished speeches, and correspondence. Lists of lodge members and extensive biographical material were also examined: personal files, applications for admission, questionnaires, rГ©sumГ©s, vouchers, and brief addresses. The third group of documents is the extensive collection of Masonic pamphlets and journals. The present study provides the first analysis of all significant German lodge journals between 1840 and 1918.38 The numerous lodge speeches are particularly important in tracing a conceptual history of terms and ideas. In contrast, for example, to lodges in English-speaking countries, speeches in German lodges constituted an established part of lodge meetings and were recorded by hand in the minutes or largely verbatim in Masonic journals. In addition, I also examine the anti-Masonic literature of the era (in particular that of the Catholic public), which was collected by government agencies or by the lodges themselves.39 The issues raised in this study could only be addressed through a combination of methodological approaches. Any attempt to write a history of past beliefs about a connection between civil society and civic virtue in terms of ideas and social practices necessarily straddles established fields and methods of historiography—even if such an attempt cannot do without social history and conceptual history (Begriffsgeschichte). The conventional separation of historiography into intellectual and social history or into cultural and political history reinforces a depoliticized notion of culture, which distorts the moral and political self-understanding of nineteenth-century “practitioners of civil society.” Such a notion of culture implicitly defines as “pre-political” precisely those questions that were eminently political for early modern political theory.40 In order to grasp this belief in the political importance of civil society’sPage 12 → social and moral

foundations, it is necessary to employ a different approach, one that investigates the political substance of these ostensibly “pre-political” concepts and practices.41 This is precisely what the present study attempts to do. While such an approach might be called a “political history of culture,” this should not be regarded as a new subfield of history with its own concepts and models.42 Rather the approach adopted in this study can be summarized in the form of a question: Which social and discursive practices have transformed ideas about the social and the moral, the national and the universal, the public and the private into objects of politics? Admittedly this question is not entirely new. Reinhart Koselleck and John Pocock have each developed approaches to the historical study of concepts and languages and to issues addressed in the present study.43 However, Koselleck’s Begriffsgeschichte and Pocock’s history of political languages have both been criticized for concentrating on canonical texts and authors and for not adequately investigating the social-political context of speech acts.44 By focusing on diachronic change in the moral-political language of actual practitioners of civil society like the Freemasons, this book attempts to take such criticism seriously. Furthermore, a political history of culture must not only historicize concepts of individual and collective identity such as class or nation. It must also engage in a cultural history of the practices and institutions tied to such identities.45 Individuals are not simply wax figures that passively assume the shape of existing moral or political discourses. The appropriation of identity occurs through a variety of individual and social practices, the results of which can contradict purely discursive concepts and terms. The rituals of Freemasons, for example, often tell us more about the politics of sociability than their speeches do. Changes in the meaning of concepts and terms, in other words, must always be connected to their actual usage in everyday practice. In this way we can historicize the question of the emergence of the modern self, a question that theorists of civil society from Tocqueville to Weber have regarded as particularly significant for politics. Foucault echoed this concern when he called for a “history of the forms of moral subjectivation and the practices of the self that were associated with it.”46 We must recognize that identities are not permanent, unified, or coherent but are instead dependent on practices of political appropriation and usage.47 Finally, we should regard the history of boundaries as yet another dimension of a cultural-historical approach to the political.48 “One could Page 13 →write the history of boundaries,” Michel Foucault wrote, “those obscure gestures, which, as soon as they have been executed, have already necessarily been forgotten—gestures with which a culture rejects something that, from its own perspective, lies outside of it.”49 Foucault refers here to precisely those boundaries that are often regarded as “pre-political,” in particular boundaries between self and other.50 But even those boundaries traditionally considered political, such as those between classes, religions, or nations, become of interest for such an investigation the moment we do not assume that they simply exist objectively in history, but rather begin to examine their gestures, mechanisms, and effects, the descriptions of self and other they invoke. It is also important to take the metaphor of boundaries literally and investigate how social spaces arise (in the case of Masonic lodges, for example, by means of the secret) and which cultural and symbolic practices establish an inside and an outside—whether in social or religious terms, or in political or gendered ones.Introduction The political utopia of the lodges sought to transcend such boundaries and to construct a social space in which “the parity of the purely human” would establish an enlightened universalism. However, the desire to transcend these boundaries, to create “a brotherhood of men” has always produced its opposite as well: the effort to set oneself apart, the desire for social and moral exclusivity, and the authority to determine who is a man and a citizen and who is not.51 Those who would like to revive political ideas of the “long nineteenth century”—its typical preoccupation with the self, civil society, and humanity—cannot avoid the political aporias inherent in those ideas simply by rejecting the notion of the nation-state.52 The binary distinctions of civilized and barbaric, enlightened and backward, masculine and feminine, or more generally, universal and particular are typical not only of the moral and political language and the curious rituals of nineteenth-century Masonic sociability.53 A historical study that investigates ambivalent identities—as a cultural history of the political just as much as a political history of culture—must, therefore, dispense with the false alternatives of universalism and particularism and explore the territory in between.54

Page 14 → Page 15 →

Part I Freemasonry and Civil Society A society rises from brutality to order. Barbarism is the age of the fact, and thus the age of order is necessarily the realm of fictions—for there is no power that would be capable of founding the order of the body solely through bodily force. For this, fictional forces are necessary. —Paul Valéry

Page 16 → Page 17 →

Chapter 1 Secrecy and Enlightenment The conceptual distinction between state and civil society is an invention of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. If the Aristotelian tradition had understood societas civilis as a community of free and equal citizens united in political self-government, the emergence of the modern state and the subsequent concentration of political power in an absolutist ruler and his bureaucracy led to a bifurcation of the term. Civil society was no longer identical with a form of political rule: State and civil society became separate entities. “Civil society” came to designate a political space independent of the state and, at least apparently, removed from politics.1 At the same time the significance of this “civil sphere” expanded. It was not merely “bourgeois society,” the domain of the economy created by the rising middle class or BГјrgertum, as Hegel and after him Marx or Riehl would claim in the nineteenth century with such momentous consequences for the conceptual history of bГјrgerliche Gesellschaft. Rather, one of the criteria of “society” in the eighteenth century was that it be “free from all the limitations that men experience as civil (= political) persons and as private persons (birth, status, profession, business).”2 Society initially encompassed a newly defined domain within the state that was understood as “civil,” a domain that expanded into a societas publica. This new “civil society” was constituted in the private spaces of sociability.3 This conceptual displacement marked not only a transformation of structural conditions, for example, the expansion of communicative networks and the development of market societies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Within these altered structural conditions, a new conception of humans and human nature was also articulated, one that unfolded within the modern polarities of the self and sociability. The older discourse of virtue in the Aristotelian tradition was transformed into the Page 18 →idea of civilizing the individual through the sociability of citizens. In his notion of the “unsociable sociability” of man—the interplay between an inclination to socialize and a tendency to individualize—Kant identified in anthropological terms the actual tension and dynamic, the antagonism of this new “civil society.” The social world appeared to be as natural as nature itself. Like nature, it was not free of conflict and yet was harmonious. “Thus the first steps from barbarism to culture are achieved; for culture consists in the social value of man. Thus all man’s talents are gradually unfolded, taste is developed.” The individual constitutes his individuality in society; society constitutes itself “as a moral whole” in the sociability of individuals.4 The fundamental principle of “civil society” is the formation of society, the association, the voluntary assembly, and interaction of individuals for the purpose of enlightening and developing themselves, society, and humanity itself. Society, or more generally speaking the “social” as a specific field of human experience, is itself historical, a topos of the European Enlightenment. In continental Europe, a temporary abolition of absolutist corporative distinctions occurred within the sociability of these new social spaces. These spaces were initially understood as private and apolitical, an understanding that was not limited to the German language area. The French term sociabilitГ©, which was coined in the early eighteenth century, was evidence of these new social practices and at the same time one factor in their emergence.5 On the one hand, the term described the rise of “European societies,” if “society” in contemporary parlance is still understood as identical with socialitas, the sociable intercourse of men as men.6 In the innumerable sociable unions of the eighteenth century, society could experience itself as society—society, as it were, occurred. In this social-moral sense, society understood itself as egalitarian, as a sphere within the absolutist state where “citizens without sovereignty could be free.”7 On the other hand, the history of society always includes the history of society’s self-description as society. “Strictly speaking, the new civil society existed only to the extent that it was able to assert itself linguistically.”8 Two factors were essential in the constitution of modern civil society: the self-constitution of society as society through concrete cultural practices in the closed social spaces of sociabilitГ©; and the selfdescription of society as society in a new “public sphere.” It is in this sense that Lessing could assert in 1779 that the noble core of Freemasonry—the most popular form of association in the eighteenth

century—was as old as civil society itself and that the two could only have emerged together.9 Page 19 → Freemasonry originated in the political culture of England and Scotland at the end of the seventeenth century, the period following the Civil War and the Revolution of 1688. Twenty years after the four lodges in London merged to form the Grand Lodge of England—Freemasonry’s actual founding date (1717)—the first German “Masonic society” was founded in Hamburg in 1737. The first Masonic lodge on the European continent had already been established in The Hague in 1731. A lodge was founded in Paris in the following year. A network of lodges then spread across the entire European continent at an astounding pace. Before the middle of the eighteenth century, it extended not only from Paris to St. Petersburg, from Copenhagen to Naples, but also to the colonies outside of Europe, for example, in New England.10 The number of lodges rose dramatically as well in the German language area. Masonic lodges were established quickly throughout Protestant northern and central Germany—the core region of the German Enlightenment—as well as in the Rhineland. In Catholic southern Germany, Masonic lodges were limited to a few cities, as Freemasonry in the eighteenth century was in general a purely urban phenomenon. Following the example in Hamburg in 1737, lodges were established in Dresden in 1738, in Berlin in 1740, and in Leipzig and Breslau in 1741. Over the course of the eighteenth century, multiple lodges were established in a number of cities. For example, the first lodge in Breslau, Aux trois squelettes, was founded in 1741 immediately after Friedrich II’s occupation of Silesia. Thirty years later, three additional Breslau lodges were established: Zur SГ¤ule in 1774, Zur Glocke in 1776, and Friedrich zum goldenen Zepter in 1776. In Leipzig, the Aux trois Compas Lodge (1741) and Minerva Lodge (1746) merged in 1747; the Balduin Lodge was established in Leipzig in 1776, and the Apollo Lodge in 1799. Myriad diverse Masonic lodges arose throughout Germany. Compared with their English or French counterparts, German lodges were particularly varied in form, which is not surprising given Germany’s federalism and its fragmented constitutional history. In Masonic lodges, “the social framework of a moral International” was established, a supranational communicative space, in which ideas and practices of the English and the Scottish Enlightenment’s political culture were discussed and implemented.11 Over the course of the eighteenth century, Masonic lodges developed into the most widespread and inclusive form of sociability of the European Enlightenment.12 According to conservative estimates, there were approximately 450 lodges with 27,000 membersPage 20 → in the German language area throughout the eighteenth century. In 1789, there were almost 700 lodges in Paris and in the French provinces, and more than 20,000 Freemasons had been registered and identified by name.13 In 1750, an Amsterdam lodge member estimated that there totalled about 50,000 Freemasons in the larger European cities.14 It is entirely possible that this number had more than doubled in continental Europe by 1789.15 “There are few people,” Baron von Knigge claimed in 1788, “possessing an eminent degree of ability and activity, particularly on the continent, who being actuated by a desire for knowledge, or by sociability, curiosity, or restlessness of temper, have not been for some time at least members of secret associations.”16 How can we explain the enormous appeal of Freemasonry? Who was drawn to the lodges’ cultural practices and new moral values? What was the political significance of Masonic lodges within the absolutist state? In what way is “civil society,” as Lessing conjectured, merely an “offspring” of Freemasonry? Despite the dizzying diversity of European Freemasonry in the eighteenth century, I will attempt to offer general answers here to these questions by emphasizing the basic traits of Masonic lodges. In the past, scholars frequently characterized Masonic lodges as communicative spaces of the socially ascendant, but politically powerless bourgeoisie. According to this traditional understanding, “civil society,” as it was concretized in the lodges, was a product of the bourgeoisie, and the Enlightenment was that class’s “ideology of emancipation.” Recent studies of French and German lodges, however, have corrected this view. Freemasonry’s particular significance lay rather in the fact that aristocratic and bourgeois elites associated with each other in Masonic lodges, with monarchs at times even assuming a leading role.17 Crown Prince Friedrich was admitted to the Prussian lodges in 1738 and was later admired as a guiding figure of

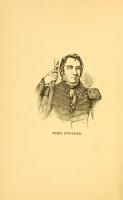

European Freemasonry. In royal residences and garrison cities the percentage of aristocratic lodge members was high, while in the large trading cities such as Hamburg, Frankfurt, or Leipzig it was low. The social structure differed from city to city and from lodge to lodge. In lodges in Berlin, KГ¶nigsberg, or Breslau, aristocrats, civil servants, and military officers long predominated.18 In a university city such as GГ¶ttingen, lodge members were primarily professors. In general, we find that over the course of the eighteenth century lodge membership was composed of the aristocracy and those professional groups classified in social-historical terms as the “new BГјrgertum”: wealthy merchants, factory owners, bankers, administrative officials, lawyers,Page 21 → doctors, scholars, clergymen, and artists. During the 1780s, aristocrats constituted the majority of lodge members in MГјnster. Around 1800, the MГјnster lodge, with General von BlГјcher as its grand master, brought together Prussian officers, senior officials, and businessmen, while the local aristocracy no longer participated.19 Until the middle of the eighteenth century in Frankfurt, aristocrats made up half of the membership of the Zur Einigkeit Lodge. They gradually resigned from the lodge, so that by the end of the century the commercial bourgeoisie in Frankfurt (many of whom were also city council members) and senior civil servants formed the bulk of the membership.20 It was not, therefore, an enlightened counterelite opposed to the absolutist state that met in the social spaces of Masonic lodges. Rather, in both France and Germany, the lodges formed “sites of social compromise” (Daniel Roche).21 The significance of Freemasonry in terms of social history lies in this mixing of traditional aristocratic culture and a new civic culture, of enlightened aristocrats and ascendant BГјrger.Secrecy and Enlightenment Fig. 1. Margrave Friedrich of Brandenburg-Bayreuth’s admission into Freemasonry, presided over by Frederick the Great. (Courtesy of the Freimaurermuseum Bayreuth.) Page 22 → In order to grasp the political significance of this development, we need to examine the cultural practices of Masonic lodges in greater detail. Precisely because the lodges erected social barriers for those below them (e.g., craftsmen), the extent of internal equality embodied in Masonic rituals was astonishing. This exclusion “below” made possible “an egalitarianism вЂabove’” (Wolfgang Hardtwig) to a degree that had as yet been unknown.22 “As soon as we are assembled, we are all brothers. However, the rest of the world is a stranger to us,” one Freemason argued in a lodge speech in 1753. “The prince and his subject, the nobleman and the BГјrger, rich man and poor man, the one is as good as the other. Nothing distinguishes any of them from each other, and nothing separates them. Virtue has made them all equal.”23 In his diary, a Freemason in Wetzlar described the (at least partial) realization of this equality at the beginning of the 1780s, which was the most lasting impression of his admission to the lodge: “The concord among the brothers, where poor and rich, common and noble sat together without rank and without pretension.” He continued, “There my spirit sang with emotions it had not been capable of until then.”24 It is less the enlightened lodge speeches than the immediate experiences of equality in interacting with lodge “brothers” that seems to explain the fascination Masonic lodges exerted.25 Shaking hands and oaths of loyalty, brotherly kisses and drawn daggers on the initiate’s bared chest simultaneously communicated and sensuously strengthened this new community. The language used in the lodges intensified the feeling of brotherhood by borrowing metaphorically from the familial domain. The grand lodges were mothers and the individual lodges were daughters; lodge members were brothers and their wives were sisters. The Masonic cult of fraternity, in other words, made possible a playful appropriation of enlightened ideas. This was one of the central reasons that the lodges became the “strongest social institution of the moral world in the eighteenth century.”26 Such an abolition of the boundaries of corporative society appeared possible only in a world of play and illusion shrouded in secrecy. For this reason, it is essential that we illuminate the connection between secrecy and the public sphere, between enlightenment and Freemasonry in order to uncover the core of the Masonic selfconception.27 Only their emphasis on secrecy distinguished Masonic lodges from other associations. Paradoxically, this transcending of particularity (e.g., differences in status) in the lodges necessitated the delineation of new boundaries. Secrecy created Page 23 →a closed “moral interior” (Reinhart Koselleck),

which promised unaffected sociability and friendship among men and thus allowed the Masonic idea of “civilizing” to be experienced in Masonic rituals. Freemasons regarded themselves as moral elites possessing and embodying a secret religion of virtue. They believed the virtue of individual citizens, their “civility,” to be the guarantee for the moral improvement of society and even of humanity itself. Thus they claimed as their exclusive possession a general humanist idea of civilization. The secret promised an exceptional degree of internal cohesion. Internally it created equality and fraternity among lodge brothers (the “initiated” and “virtuous”), while externally it excluded the “uninitiated” and the “profane.” In this way, secrecy mediated the opposition between general-humanist claims and social-moral distinctions: It was egalitarian within and elitist without.Secrecy and Enlightenment As Georg Simmel has noted, secrecy offered a second world alongside the visible one, and both worlds influenced each other substantially.28 The lodges created a stage on which the world of the European ancien rГ©gime could be presented once again. At the same time, they called this world into question in a “theater of morality” (Norbert Schindler), offering a second world, an outline for a new social-moral order.29 A veil of fictional traditions, myths of origins, and symbolic actions disguised the novelty of this order. The dramatized crossing of the threshold into the harmonious space of morality—a classic rite of passage—formed the center of the Masonic cult of secrecy. Only through the estrangement that the theatrics of Masonic mysteries created could individuals recognize a new morality as the path to “beauty,” “wisdom,” and “strength,” to self-improvement, self-knowledge, and self-control—the three “Masonic lights,” which provided orientation in working the “rough stone,” in perfecting one’s self through sociable intercourse with lodge brothers. The “irrational” enthusiasm for secrecy, playfulness, and mysteries was not exhausted in the esoteric, as a superficial evaluation of the Masonic world might suggest.30 Turning away from the outside world and engaging in playful interaction within the lodges was a necessary prerequisite for creating this free space, in which a new society could unfold, a society in which the most diverse ideas and opinions, imagination and passions could be developed.31 However, secrecy not only allowed for more intense and freer forms of sociability. It also provided a protected space for the process of individualization, the unfolding of individual subjectivity. “Secrecy assumes the function of creating a site for the impulses and claims arising from this expanded and deepened interiority, a site where they could express themselves,Page 24 → but where, at the same time, discretion is maintained regarding civil society.”32 The individual stood at the center of Masonic initiation rites; the attention of the brothers was directed at the applicant being initiated. For most lodge members, the true secret of Freemasonry was the experience of this ritual, that is, the intensification of one’s own experience as an individual on being admitted to the community of brothers. But didn’t the Masonic cult of secrecy contradict the culture of the Enlightenment, which was apparently focused on the public sphere and rationality? As Norbert Schindler emphasizes, Freemasonry, as “a symbolically disguised secret cult, certainly accorded with many playful dimensions of courtly culture, for example, its fashionable tendency to temporary self-mystification expressed in its passion for dressing up, for the theater, and for masquerade.”33 The innumerable secret societies formed a colorful and diverse world of play and illusion, which both reflected the old order and announced the new one. The spectrum reached from secret political brotherhoods such as the Illuminati up to occultism, from Weishaupt to Cagliostro. It is this mixture of reason and play, of rationality and the search for the exotic, that gives the lodges their fundamentally modern appearance. While it is impossible to examine in detail the colorful and in part contradictory diversity that emerged here, we can identify two general tendencies within the world of the lodges: English Blue Masonry with its more simple rituals and symbols and its three moral levels (Apprentice, Fellow, Master); and beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, Scottish Rite Masonry, originating in France, which had an elaborated system of knightly rank with up to thirty-three degrees and which dressed itself in the garb of a new crusade. It would be simplistic to try to distinguish here between a “bourgeois” and an “aristocratic” variety of Freemasonry. Many Scottish elite high degrees such as “Le Chevalier de l’Orient” or “Le Chevalier de la Rose-Croix” evoked a fashionable aristocratism and mysticism. Other high degrees such as the “Symbolic Master” exaggerated the enlightenment itself into a religion.34 Again, the mixture of aristocratic

and bourgeois practices is remarkable. The internal structure of the lodges combined democratic-republican principles with hierarchical-monarchic ones.35 The democratic ballot for the admission of new lodge members and the election of Masonic “officials” stood in stark contrast to the hierarchical structure of the lodges. Even if the adoption of English Freemasonry in the European ancien rГ©gime transformed it in diverse ways (up to the reversal of its original goals), the cultural practices of the lodges remained tied to Page 25 →the context in which they had originated (at times in ways that were not clear to contemporaries): the political culture and the emerging civil society of England following the Revolution of 1688–89.36 The dizzying diversity and the hilarious playfulness of secret societies in the eighteenth century have often distorted the fact that the lodges were a part of this moral and political tradition.Secrecy and Enlightenment Nevertheless, the history of individual lodges in the eighteenth century was in fact quite varied and could at times assume comical dimensions. For example, the Minerva Lodge, founded in 1741, operated initially according to the simple English rituals. Leipzig’s elite made up the membership of the lodge. Members of the Minerva then established not only the other Masonic lodges in the city but other associations as well, including the elite Harmonie Society in 1776. The Minerva Lodge, with its typical mixture of aristocrats and BГјrger (the latter, admittedly, formed the majority), united the prosaic and practical need for business and social contacts with the diffuse yearning for an otherworldly elitism. In order to maintain their advantage in the competition for prestige with newer lodges and associations, the Minerva Lodge adopted the ostensibly aristocratic and more traditional “strict observance” in 1776.37 As the term suggests, strict observance required unconditional obedience to “secret superiors” and was ostensibly derived from the legendary order of the Knight Templars. According to its founding myth, the Templars retreated to Scotland in 1314, after their last grand master, Jacques de Moley, had been burned at the stake, and continued to work there in secret—in the form of Freemasonry. Beginning in the 1730s, these legends spread throughout France. Here Baron von Hund became familiar with them and then introduced them to the German language area. By the middle of the eighteenth century, “strict observance” had become quite widespread, employing a series of rituals and practices that drew imaginatively upon the traditions of the Templars: The world was divided into provinces, the chapter of knights into their prefectures; cities were given their old names, the members of the orders a nom de guerre and their own uniform—white jackets with a red Templar cross as well as purple jackets and light blue vests, daggers, and feathered hats. The passion for dressing up and for a playful aristocratism and medieval myths accorded with the diffuse yearning for a conservative Christian humanity, one that heralded a “growing affront to ecclesiastical rationalism, popular enlightenment, and the spirit of individualism.”38 Attempts to revive the Templar Order were ended only at the Masonic convention in Page 26 →Wilhelmsbad near Hanau in 1782.39 The Minerva Lodge, however, did not want to give up part of the fanciful rituals and even retained them in a modified form, after it had been presented with the simplified rituals drawn up by Friedrich Ludwig SchrГ¶der, a Hamburg theater director. In both form and content, SchrГ¶der’s rituals marked a return to English Blue Masonry and its liberal humanist message. However, the more socially elite the members of a lodge were, the more likely it was that the lodge would retain traditional rituals, as is evident in the example of the Minerva, which was viewed in Leipzig as an “aristocratic lodge.”40 The other two Leipzig lodges, the Balduin and the Apollo, which were more unambiguously bourgeois, adopted SchrГ¶der’s ritual, as did a majority of German lodges outside of Prussia after 1800.41 Another example, that of the Friedrich zum goldenen Zepter Lodge in Breslau, is even more intricate. In 1823, the lodge’s grand master, Johann Wilhelm Oelsner, a factory owner, writer, and Breslau city councillor, provided an indignant summary during a retrospective on the history of Masonic lodges during the 1780s: “Not infrequently the effectiveness of our lodge has been impeded by enthusiasm and numerous foolish opinions introduced by the spirit of the age and spread to a number of lodges.” He also wrote the following about the lodge’s grand master at the time, Gottlieb Friedrich Hilmer, an adherent of “strict observance”: “Devoted to extreme ideas of occultism and spiritism and to foolish principles, he sought in vain to make his opinions general. As a result, divisions arose within the lodge.”42 Hilmer had joined the Rosicrucians in Paris, an anti-enlightenment secret society similar to “strict observance, ” which had gained political influence after the death of Friedrich II in Prussia in 1786. King Friedrich

Wilhelm II was himself a member of the Rosicrucians; his ministers Woellner, Bischoffswerder, and Count Haugwitz were the principal leaders of the order. In Breslau, the Duke of WГјrttemburg was a leader of the Rosicrucians as well as the Zepter Lodge. Hilmer owed not only his professorship at the MagdalenГ¤um Gymnasium in Breslau but also his position as grand master of the Zepter Lodge to the Duke’s influence. The members of the Zepter were primarily aristocrats and officers. It was only in the late 1780s that members of the BГјrgertum joined the lodge, including Georg Gustav FГјlleborn, a professor of classics at the Elisabeth Gymnasium, who assumed the office of lodge speaker. A student of Kant and Christian Wolff, FГјlleborn had apparently attempted to influence lodge brothers in a “more rational” direction. Thanks to his influence, “pure morality, rather Page 27 →than moneymaking and spiritism” first entered the lodge in the middle of the 1790s. As a result, many of the aristocratic lodge brothers resigned. They apparently regarded FГјlleborn’s calls for self-inspection and the fulfillment of moral duty as presumptuous.Secrecy and Enlightenment There had been similar conflicts in many German lodges beginning in the 1760s. Masonic lodges became “publicist sites in which an initial polemic encounter between proto-conservatism, political liberalism, enlightenment, and ecclesiastical orthodoxy occurred.”43 In 1795, the lodges in Breslau were closed down. The lodge chronicle reported, “The unrest in France namely and the discredited notions of freedom and equality have made Masonic lodges . . . suspicious and created a number of disadvantages for them.”44 Like many other Prussian lodges, the Zepter Lodge reopened on a regular basis only after the turn to the nineteenth century, now under royal patronage and subject to the political supervision of the Zu den drei Weltkugeln Grand Lodge in Berlin. The suspicions regarding secret societies and the attacks on them (which arose with the expectation of revolution and not merely with revolution itself) called attention to the political ambivalence of the cult of secrecy, with its mixing of aristocratic and bourgeois, hierarchical and democratic, mystifying and enlightened ideas and practices. The suspicions extended from the enlightened rebuke that Freemasonry was merely “fashionable foolishness” to counterenlightenment myths of conspiracy. Both of these suspicions testified to a politicization of society, which was reproduced in secret societies with the Rosicrucians and the Illuminati on opposite ends of the political spectrum. The Scottish Rite system, with its high degrees and its tendency to idealize the Middle Ages, was not the only link between enlightenment and romanticism. The ostensible contradiction between secrecy and publicity, between occult illusory worlds and enlightened-rationalist ideas is actually typical for enlightenment societies in Europe in the eighteenth century.45 The cult of secrecy was not only an imitation of courtly culture with its fondness for self-mystification and its play with masks. It also imitated the arcana of absolutist politics and competed at least indirectly with it. Secrecy made possible a space in which the moralpolitical imagination could be unleashed. In these spaces suspended from social reality, a mixed elite was socialized according to a recognizably modern civic ethos of self-discipline, virtue, and Bildung, an ethos that always included a transgression of traditional boundaries.46 Even if the brothers in the lodges pledged their loyalty to the state, they also undermined the old order by “offering a new ethically grounded Page 28 →value system, which necessarily implied a condemnation of the principles of absolutism.”47 Not only lodges’ speeches and discussions but also the cultural practices of the lodges acquired a political significance. Both the appeal of the lodges and their explosive political force were based on the fact that they had created a new space removed from the state, in which political reality was suspended and in which a wild variety of ideas and opinions, passions and interests were circulated and discussed. In the lodges, society could invent and experience itself, could live the fiction of an order free of domination, could live the Enlightenment. At the same time, the lodges also anticipated the limits of this new order of civil society and at least attempted to mitigate the sharpness of those limits. Lessing himself was aware that the idea of a sociability based on the “parity of the purely human,” as he described it in his Masonic Dialogues, contained a utopian surplus that would not merely reconcile the divisions in society but eradicate them completely. He warned, “To remove them [i.e., the divisions in society] completely . . . would at the same time destroy the state together with them.”48 The participants themselves may not have been aware of this “subversive” side of Masonic sociability, but the average lodge brother did understand

that the free sociability of aristocrats and burghers—and thus the transgression of corporative boundaries—was politically explosive. In addition, the lodges’ disregard for disputes between the Catholic and Protestant Churches, the decisive domain of politics up to the eighteenth century, was of enormous significance. Members of Le Secret de trois Rois Lodge, founded in Cologne in 1775, included both Catholic city council men and Protestants, who had yet to be granted civil rights in Cologne at the time.49 By around 1750, the Minerva Lodge in Leipzig began to admit Calvinist merchants as members. This enabled Calvinists to socialize with Leipzig’s city elite long before they were granted civil rights in 1811, even if the University of Leipzig with its strong Lutheran orthodoxy opposed such openness.50 In the Zur Einigkeit Lodge in Frankfurt as well, many of the lodge brothers were Calvinist Г©migrГ©s or Catholic merchants. Freemasonry’s claim to transcend confessional differences thus had a concrete significance for the legal emancipation of this section of the nascent bourgeoisie, which had not yet been integrated politically but had become increasingly powerful economically.51 Secrecy stimulated the imagination, cultivated interest in new forms of knowledge, and established a moral authority that competed with the church and the state. In The Constitutions of Freemasons (1723), Anderson Page 29 →stipulates that Freemasonry can only oblige the brethren “to that Religion in which all Men agree.”52 Even if we reject Carl Schmitt’s glorification of the absolutist state and his Jewish-Masonic conspiracy theory (a modified version of AbbГ© Barruel’s theses), Schmitt did correctly recognize that this distinction between internal faith and external belief, between private and public allowed space for the establishment of modern individual freedom of thought and freedom of conscience in opposition to the absolutist state.53 The fact that Freemasonry itself at times assumed dimensions of a civil religion allowed it to transcend religious differences. The deism endorsed by Freemasons—that of an “Architect of all worlds”—contained at least potentially a precept of tolerance.54 In the moral interior of the lodges, brothers regarded the vision of a virtuous civil society—the inheritance of Freemasonry’s English origins—as superior to the ruling political and ecclesiastical order. “Freedom in secret became the secret of freedom.”55 Masonic lodges were ultimately able to disregard not only differences of confession and corporative status but also those of state citizenship. “In the lodges, a brother ceased to be a political subject (Untertan); he was a man among men.”56 Consequently, Freemasons saw themselves not only as subjects or citizens (StaatsbГјrger), but as cosmopolites (WeltbГјrger). The lodges possessed a supranational communicative network. We should not underestimate the significance of this network in promoting the circulation of enlightened ideas. When traveling, Freemasons could visit lodges in other cities, and they often participated in local sociable circles. Membership in secret societies was a kind of “sociable bill of exchange” that could be redeemed anywhere.57 Lodges often corresponded with each other, exchanged representatives (on the level of grand lodges), and circulated printed material and information. In these transnational entanglements, the feeling that one was a cosmopolite assumed a concrete meaning. Masonic lodges were more cosmopolitan than almost any other social institution of the eighteenth century.58 In an 1890 essay, the sociologist Georg Simmel offered a theoretical explanation for the popularity of Masonic lodges as institutions in the eighteenth century: The social process of differentiation caused a shift in emphasis from the corporative significance of subjects to the cultivation (Bildung) of individuality, and this shift was accompanied by an orientation to ideal units, a “cosmopolitan disposition.” “The more attention is focused on man not as a social being but as an individual, and hence on those qualities that are his purely as a human being, the closer the connection must be that Page 30 →draws him away from the particular social group to all that appertains to human beings, suggesting an ideal unity of mankind.”59 Bildung and sociability as the path to the moral improvement of the individual and thus that of the community and of humanity as a whole—this was the utopian core of both Freemasonry and the European Enlightenment. Yet while Freemasonry’s transgression of traditional social, religious, and political limits was astonishing for the eighteenth century, new limits also emerged in the process. As Lessing noted ironically, the cult of fraternity encompassed essentially only the new aristocratic, bourgeois elite.60 Religious tolerance did not yet apply to the Jewish faith. During the “enlightened” eighteenth century, not a single Jew was admitted to an officially

recognized Masonic lodge in Germany.61 Nevertheless, isolated Jewish Freemasons who did not identify themselves as such were tolerated as “visiting brothers.” We should also bear in mind that the “pure” human beings in Masonic lodges stripped of all corporative, religious, and national affiliation were exclusively men. There were lodges for women in France, the so-called adoption lodges, which were subject to the patronage of male lodge brothers. These lodges were not recognized outside of France and were disbanded after 1789.62 While the refusal to admit Jews led to almost no discussion within the lodges, the exclusion of women from the “brotherhood of men” appeared to require an explanation even in the eighteenth century. Herder’s Adrastea (1803) offered one widespread justification for this exclusion. Like Lessing, Herder was himself a Freemason but was critical of existing lodge practices. In Adrastea, Herder attempted to continue Lessing’s Masonic Dialogues with his own dialogue on the “purpose of Freemasonry as it appears from outside.”63 In addition to the two male figures, Faust and Horst, neither of whom are Freemasons, Herder introduced the figure of Linda into the dialogue, a “Freemason by birth.” Although Linda is enthusiastic about Freemasonry, the secret society is not open to her. In response to Linda’s question as to why she is refused admission, Faust answers that women have never required the distinction between purely human duties and civic duties. “Fortunately you are nothing in civil society; you always require a guardian. In human society, nature has entrusted you with the dearest seeds, with its most beautiful treasures.” In other words, since women possessed neither economic nor legal independence, they had no place in civil society. While men “bear the burdens of civic life for themselves and for you [i.e., for women],” women continue to live “in the paradise of domestic society as the educators of humanity.” Men are compelled Page 31 →to develop in civil society, in public space, whereas women can develop in private, in “purely human” spaces. As a consequence, women do not require a sociability that seeks to overcome the divisions of civil society and that aims at the “purely human.” Linda herself defines the lodge as a “closed society of men, effecting in silence and advising on the welfare of humanity, . . . for which its work must remain to a certain degree a secret and upon which they labor as if it were an infinite plan.”64 The new type of citizen propagated by the lodges was perhaps “the first universal humanist social type.”65 However, the partial undressing, the playful humiliation, and the assistance offered by lodge brothers during Masonic rituals implied a rather different message. These practices reminded the initiate that although he had removed all external signs of his origins, he had brought with him the most important presupposition for his Bildung: his male body.66 It is the male citizen who can and should improve himself, improve civil society, and ultimately improve humanity in general. These distinctions between public and private, between masculine and feminine spaces and gender roles that were so fundamental for civility in the nineteenth century were formulated and enacted in advance in Masonic lodges at a time when these distinctions had not yet been established and were not yet generally accepted. It is only in the early nineteenth century that the civic era of German Freemasonry began in the sense that a particular moral-political discourse became prevalent in Masonic lodges and that the BГјrgertum predominated there. This in itself illustrates the ambivalence in Freemasonry’s own self-conception between universal humanist claims and social exclusivity, between the public sphere and the secret. The disputes that now arose regarding the participation of Jews and women in the “brotherhood of men” indicate the lodges’ changing self-conception as well as their altered significance within civil societies of the nineteenth century. The lodges gradually developed “from moving forces and publicist enclaves of civic public spirit to entities that sought, as the very basis of their existence, to distance and separate themselves from the existing public sphere.”67 The “women’s question,” the “Jewish question,” the question of religious tolerance regarding the “dark powers” (i.e., Catholics), the “social question,” the constitutional question, and the justification of national wars—all of these inevitably became central issues for a sociability that claimed to have established a domain beyond status, religion, and nation, a domain of exclusive humanity.

Page 32 →