The Lady of Linshui: A Chinese Female Cult 9781503620575

This anthropological study examines the cult of the Chinese goddess Chen Jinggu, divine protector of women and children.

184 24 16MB

English Pages 392 Year 2008

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

The Lady of Linshui

ARC Asian R e l i g i o n s & C u l t u r e s Edited by Carl Bielefeldt Ber nard Faure

Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism Fabio Rambelli 2008

Eccentric Spaces, Hidden Histories: Narrative, Ritual, and Royal Authority from The Chronicles of Japan to The Tale of the Heike David T. Bialock 2007

Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China Fabrizio Pregadio 2006

Chinese Poetry and Prophecy: The Written Oracle in East Asia Michel Strickmann Edited by Bernard Faure 2005

Chinese Magical Medicine Michel Strickmann Edited by Bernard Faure 2002

Living Images: Japanese Buddhist Icons in Context Edited by Robert H. Sharf and Elizabeth Horton Sharf 2001

Brigitte Baptandier tran slated by k ristin ingrid fryklund

The Lady of Linshui A Chinese Female Cult

Stanford Universit y Press Stanford, Califor nia

Stanford University Press Stanford, California English translation © 2008 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. The Lady of Linshui was originally published in French in 1988 under the title La Dame-dubord-de-l’eau by Brigitte Berthier © 1988, Société d’ethnologie. Translator’s note and author’s additional material © 2008 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. This book has been published with the assistance of the Dean of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Baptandier, Brigitte. [Dame-du-bord-de-l’eau. English] The Lady of Linshui : a Chinese female cult / Brigitte Baptandier ; translated by Kristin Ingrid Fryklund. p. cm. — (Asian religions & cultures) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-4666-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Goddesses—China. 2. Women and religion—China. I. Title. BL1812.G63B3613 2008 299.5'142114—dc22 2007049941 Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/14.5 Sabon

c onten ts

List of Illustrations Preface

vii

ix

Translator’s Note

xiii

Introduction

1

1. Sexual Categories

43

2. The Goddess of Pregnancy Has an Abortion and Returns to Mt. Lü

65

3. The Bridge of a Hundred Flowers

85

4. Cinnabar Cloud Monkey

105

5. The Thirty-six Pojie

123

6. The God of the Soil and the Lady of the Birth Register

142

7. Women and the Temple: The “Celestial Flower”

166

8. Children and the Temple: The Passes (guan)

196

9. Rituals of the Flowers and Passes

222

10. Chen Jinggu’s Medium Conclusion Notes

259

265

Bibliography Index 349

242

321

l i s t o f illu str atio n s

I.1

Chen Jinggu dancing for rain, Baihe, Taiwan

13

I.2

Mount Lü ritual master, Tainan

32

I.3

Linshui Temple main gate, Daqiao

37

I.4

Linshui Temple ritual theater stage, Daqiao

38

I.5

The Three Ladies with the Qilin, Linshui Temple, Daqiao

39

I.6

Great Ritual Academy of Mount Lü, Longtan jiao, Fuzhou

40

1.1

Luoyang Bridge

44

1.2

Chen Jinggu meets Tigress Lady Jiang

47

1.3

Chen Jinggu drives out the White Snake

51

1.4

Chen Jinggu revives Liu Qi

52

1.5

Ancestral temple of Liu Qi, Zhongcun, Daqiao

56

2.1

Ancestral temple of Empress Chen of Linshui, Tating, Fuzhou

67

2.2

Chen Jinggu cuts off a piece of her flesh to heal her parents

71

2.3

Chen Jinggu withdraws to Linshui

74

2.4

Mount Lü ritual painting: Ritual for rain

78

3.1

Chen Jinggu meets the Ravine Demon

99

3.2

Mount Lü ritual painting: Lin Jiuniang captures the Ravine Demon

101

3.3

Chen Jinggu battles the Spider Demon

102

4.1

Great Sage Equal to Heaven and Journey to the West characters, Banling, Fujian

107

viii

Illustrations

4.2

Cinnabar Cloud cultivates the Dao

109

4.3

The Rock-Press Women

112

4.4

Ritual masters writing ritual requests, Banling, Fujian

120

5.1

Generals of the Five Directions, Tating, Fuzhou

136

5.2

The siege of Fuzhou led by Wang Jitu

137

5.3

Pojie, Linshui Temple, Daqiao

140

7.1

The flower palanquin with Huagong and Huapo, Tainan

185

7.2

Linshui Temple, Tainan

193

9.1

Mount Lü ritual master with silver ritual horn, Daqiao

224

9.2

Mount Lü ritual master tracing talismans, Daqiao

225

9.3

Children’s substitutes, ritual bows, and soul receptacle, Daqiao

228

9.4

Crossing the pass, Linshui Temple, Tainan

236

9.5

Crossing the pass, Ritual Master Ma, Daqiao

237

9.6

Divination with an egg, Daqiao

239

9.7

Beidou bushel with children’s substitutes and souls, Daqiao

240

p r efac e

La Dame-du-bord-de-l’eau was published in 1988 by the Society of Ethnology, in Nanterre. It grew out of my doctoral dissertation, which I defended in 1983. The book consisted of two parts: an analysis of the legends of the goddess Chen Jinggu, the Lady of Linshui, through the “novel” (xiaoshuo) Linshui pingyao zhuan, and an ethnological presentation of my work in the field in Taiwan in 1979–80. There I “explored” the collection of legends about Chen Jinggu by following the clues presented by the first temple to Chen Jinggu on the island, in Tainan. The divinities there gave me a way to approach the novel: Chen Jinggu and her ritual sisters Lin Jiuniang and Li Sanniang, Zhusheng Niangniang, Cinnabar Cloud Great Sage, the Ladies of the thirty-six palaces of the king of Min, the god of the soil, and the guardians of the Bridge of a Hundred Flowers, over which the goddess rules. The first two chapters of that book analyzed the episodes that established the cult: the legend of Luoyang Bridge, the relation to Guanyin, and the division of the sexual categories that could be inferred from them, followed by the crucial episode of Chen Jinggu performing the ritual of “liberation from the womb” (tuotai). The second part presented the temple in Tainan. I discussed the principal rituals performed on behalf of women and children as I observed them there, and described the procedures of the “ritual masters” (fashi), “Red Head masters” (Hongtou) of the Mount Lü sect, the ritual tradition of which Chen Jinggu is the master. The final chapter was an encounter with the goddess through her medium in Tainan, Xie Fuzhu, who allowed me to observe her practice during my stay there. An inquiry into representations of the feminine as they appeared in this local cult, which arose in the Tang dynasty and was canonized in the Song, and which is still ix

x

Preface

very active today, guided this monograph. For this stage of my research, I want to express my thanks to K. Schipper, who, understanding the object of my thinking, opened before me this road. Academia Sinica of Taiwan made it possible for me spend a year in Tainan (1980) by inviting me as a Visiting Research Scholar. A “Cultural Regions” grant from the Ministry of Universities, in Paris, provided the means. Since 1986, as a researcher at the CNRS, in the Laboratory of Ethnology and Comparative Sociology (Université de Paris X, Nanterre), I have continued my field research in Fujian, the former country of Min, the place of origin of the cult of the Lady of Linshui and of the local tradition of the Mount Lü sect (Lü Shan pai). The places that the legends present are still identifiable there today, and the divine figures of the legends still receive offerings there. The mother temple, at Daqiao (in Gutian district in the north of the province), the temple in Fuzhou, and the temples in each district and village, were like so many open books recounting the myths of the kingdom of Min. The different layers of the cult and its relations to other local cults could be clearly read there. Observing the resurgence of the cults, and the unceasing rebuilding of temples that accompanied this resurgence, enabled me to analyze the “reinvention” of this ancient tradition, the “re-enchantment” carried out by its faithful in the context of the economic upheaval of modern China. The masters of the Mount Lü sect are also there and their practice is a choice site for understanding how a local ritual tradition develops and enriches itself thanks to its numerous borrowings over the centuries. In Fujian I met other mediums and the faithful of this cult, both men and women, who taught me a great deal. The republication of the Mindu bieji enabled me to re-situate the myths of Chen Jinggu in the global context of the region. The rehabilitation of the cult by the Chinese authorities and the research carried out by the Bureaus of Culture and Religion, which gave rise to two conferences (1993, 2003) and to publications with which I was associated, gave me an overview of the ensemble. I am indebted to Xu Gongsheng, the late Chen Zenghui, and Lin Jinshui, professors at the Higher Normal College in Fujian, for their hospitality in Fuzhou. Ma Xisha and Han Bingfang, professors at the Institute for Research into World Religions (Shijie zongjiao yanjiu suo) of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan), in Beijing, likewise generously supported me. I participated in the Chinese Popular Culture Project organized at the University of California at Berkeley, in 1989, by David Johnson on the theme of Rituals and Scriptures, as did Michel Strickmann, whose subse-

Preface

xi

quent death represents the loss of a great scholar and an original thinker. There, the enlightening views of Kenneth Dean, Gary Seaman, and Allen Chun, as well as those of Edward Davis and Bernard Faure, encouraged me to pursue this exploration. On that occasion, I had the chance to meet Phyllis Brooks and the late Edward Schafer, whose works on the kingdom of Min and on the Tang dynasty were particularly valuable to me. Later, my research in the field resulted in articles on rituals, talismanic writing, dreams as divinatory practice, and on the trance understood as a development of the self. I am very grateful to Philip Clart, Alison Marshall, Meir Shahar, and Robert Weller for sharing with me their own research and publications. I was considering publishing an annotated translation of the Linshui pingyao zhuan to make available this wealth of local information, and thinking of writing another work on this cult, from the time of its inception up to the present day. Then, in 2003, Bernard Faure, Kristin Ingrid Fryklund, and Mark Edward Lewis suggested translating La Dame-du-bord-de-l’eau for Stanford University Press. It seemed to me a shame to republish the same work without incorporating some of the research I had carried out in the meantime. But the problem was how to rework the old manuscript without turning it into another book; it was a challenge, but also an unexpected opportunity. I therefore decided to keep the outline and structure of the earlier work as I had conceived it at the time, and incorporate the research I had carried out in Fujian. The ideas gleaned over the years in the course of reading numerous works published since that time on other local cults, other divinities, and immortals (U. A. Cedzich, K. Dean, C. Despeux, Hsü Xiaowang, P. Katz, Lin Guoping, S. Sangren, Ye Mingsheng, Yü Chun-fang), on the period from the Tang to the Song (E. Davis, P. Ebrey, P. Gregory), on certain aspects of Daoism (J. Boltz, R. Hymes, D. Overmyer), on Buddhism (B. Faure, M. Strickmann), on mediums (P. Clart), on therapeutic traditions and medicine (C. Furth, E. Hsü), on pilgrimages (S. Naquin), on women, children, and gender studies (A. Behnke-Kinney, F. Bray, V. Caas, F. Héritier, A. Waltner) were a great help to me in this undertaking. It is of course impossible to mention all those to whom I am indebted for their work and publications. At the same time, my institutional affiliation with a laboratory of ethnology that takes a strictly comparative scientific approach privileging work in the field also influenced my work. With the patience of Kristin Ingrid Fryklund and Mark Edward Lewis I thus rewrote the work chapter by chapter. Consequently, The Lady of

xii

Preface

Linshui is not, strictly speaking, a translation of La Dame-du-bord-del’eau. Nor is it an entirely new book, either: the chapters have the same titles and the structure is the same. It is the same work, transformed from the inside out. I especially want to thank Kristin Ingrid Fryklund for her translation. She captured the tone of the manuscript while carefully preserving the meaning. It was a pleasure to work with her. I am also grateful to Mark Edward Lewis for reading through the manuscript and for his many suggestions. I am indebted to Bernard Faure and Carl Bielefeldt for including this book in the series Asian Religions and Cultures. My first contact with Stanford University Press was with Muriel Bell. I want to thank Joa Suarez and Carolyn Brown for their efficiency and kindness, and Richard Gunde for meticulously going over the manuscript. I, of course, am solely responsible for the errors that remain.

t r a nslato r ’s n o te

I would like to thank Brigitte Baptandier for all of her help in preparing this translation. She sent me the revised chapters one by one as she completed them, and verified the accuracy of the English text. Where necessary she suggested corrections. It was a pleasure to work closely with her. I would also like to thank my husband, Mark Edward Lewis, who first brought this book to my attention. He regularly taught a series of courses on Chinese religion at Cambridge University, and wanted to use La Dame-du-bordde-l’eau for the course on women in Chinese religion. The book was particularly important because of its unique focus on the female body and the physical aspects of childbirth, abortion, and childhood diseases. Since it was unavailable in English, he suggested I translate it. When I read the book, it explained rituals that I myself had observed in Taiwan in the 1970s and attitudes of my Chinese women friends toward health, pregnancy, and motherhood. I consequently found it fascinating and was eager to translate it. I would like to thank Mark Edward Lewis for reading the translation with the revised French chapters in hand; he corrected many errors and suggested improvements. In the end, the translation is even more valuable since it incorporates the fruits of Professor Baptandier’s research in the years since the publication of La Dame-du-bord-de-l’eau. We hope that students of Chinese religion and gender studies will find it useful. K. I. F.

xiii

The Lady of Linshui

i n troduc tion

The subject of this study is the legend and cult of Chen Jinggu, the Lady of Linshui (Linshui Furen). Chen Jinggu is the protector of women and children, or, more precisely, of pregnancy and childhood, defined as the time between the moment of conception and adulthood. In the mainland province of Fujian as well as in Taiwan, she is also the˝21 master of the ritual line of the Three Ladies (Sannai), which in the twelfth century became the Pure and Perspicacious Tradition of the Three Ladies of Mount Lü (Jingming Lü Shan Sannai pai) (see Chen Yi, 1993: 137). And finally, she is the inspiration behind several spirit medium cults. It was a long journey that led me to Chen Jinggu and allowed me to discover her world, which, at the very beginning, seemed to hold no surprises beyond simple fertility rites, but which little by little was revealed to be the expression of an elaborate meditation on the sexual categories, and, at the same time, a ritual tradition of exorcism and treatment imbued with a syncretism representative of the era in which it developed. My first idea for this work was to show the discourse applied to the feminine, to ask what it means symbolically “to be a woman” in China, in order to illuminate the practices that characterize the division of the sexes. This procedure was made relevant by the fact that the religious history in 1

2

Introduction

the strict sense called “Chinese,” that of Daoism and the popular religion that is a manifestation of it, revolves around the pivotal idea that is none other than the search for the feminine.1 From then on, I contemplated different approaches. In the field of gender studies a number of works of history and anthropology constitute very valuable contributions on the place of women and their role in Chinese societies of different periods. But for me a “link” was missing between the sociological materials collected from women in the field and the feminine cosmogony emanating from the myths handed down through the texts. At the same time, the tradition of internal alchemy provided a possible field of study as a metaphoric discourse on the genders and the feminine. A number of scholars have taken this route. Works on female alchemy and studies of medicine particularly interested me. Such was not my path, however, because as an ethnologist I wanted to find a way to combine research on the texts with work on the ground. The tradition of the Celestial Masters of the Zhengyi ritual line combines Daoist procedure and liturgical tradition. It is active today. However, although we cannot deny the important presence at its center of women, who have occupied the highest ranks, it nevertheless seems to be the expression of a male point of view on this journey “in reverse” (ni) appropriated by the Daoists (Schipper, 1982b: 83). In fact, in the liturgical organization of the country, it was principally a matter of first of all allowing the local elite of the village or district to be recognized as such alongside the imperial administration.2 It is thus truly a question of a society of men. The proof of this is the disappearance today of parity between men and women in the performance of ritual, due to the masculine organization of society. As K. M. Schipper emphasizes: “In the Middle Ages, the performance of ritual called for a parity of men and women, and the wives of dignitaries were of the same religious rank as their husbands. . . . The disappearance of lay female Daoshi, Master of the Dao, is quite simply due to the evolution of a modern society that imposes a masculine presence in transactions with the heads of communities and guilds” (Schipper, 1982b: 83). That this community, through the Daoist religious act, seeks the feminine while basing itself on a past of faithfully transmitted texts strictly situates it on the symbolic level: Laozi was not a woman, and it is due to this fact that in the myth the gestation of his own self, the world, becomes meaningful. Even more revealing, therefore, is the fact that liturgical duties, and therefore sacred texts, originally could be handed down in the maternal

Introduction

3

line as well as the paternal (Schipper, 1982b: 83). However, in the transmission of the writings, this inheritance of the “bones,” as they are called, the “original body,” lost its integrity; only the masculine part involved in the conception remained.3 This also explains the custom of sacrificing texts and the rejection of bloody sacrifices by this tradition.4 My task, starting from this point, was to rediscover “upstream” this “body,” its origin. The cult of Chen Jinggu and the ritual tradition of the Three Ladies (Sannai) offered me this alternative. It is not that we find there, in reality, a “more feminine” society or a system of thought emanating from women and different from the others. It is because the language of its myths tells the story of a woman and, more precisely, the tearing apart of her fate between her “real” life in Chinese society and her search for the “alchemical” development of the self. The two aspects intertwine and weave the plot of the story against a background of ritual traditions that were themselves intermixed by the syncretic spirit of the time in which they were born. The cluster of ideas of this tradition can still be seen today in China and Taiwan. This is what I spent my time doing in Taiwan (between 1979 and 1986) and later in Fujian. What, then, do we know of the cult of Chen Jinggu, which originated in the country of Min, was canonized in 1241 during the Song dynasty, and which forms part of the living accretion of Chinese religion?5

Chen Jinggu Very few texts have come down to us on the subject of Chen Jinggu: many works have been lost. Some sources, all the more valuable because they are rare, are nevertheless still accessible. These are the records or local gazetteers of the district of Gutian in Fuzhou prefecture, the place of origin of the cult, which reproduce the memorial written by a scholar of the Ming dynasty, Zhang Yining, himself from Gutian, on the subject of the development there of the cult of Chen Jinggu. There are also different versions of the Soushen ji, collections of biographies of divinities, and inscriptions set up in front of her temples, which tell the story of her divinization. All these very brief documents have the advantage of revealing the roots of this cult as much in space—the country of Min—as in time—the Tang dynasty (618–907), when Chen Jinggu lived as a human being, the beginning of the period of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms (907–979), when the mythical story takes place, and the Song dynasty (960–1279),

4

Introduction

when she was canonized. I reproduce here in their entirety the most significant of these texts, in order to let them speak for themselves, without attempting to comment on them. Many of the themes they evoke and the figures they introduce will naturally find their place later on in this study.

The Sources Chen Jinggu is first and foremost presented as a shaman (wu), born in 767 during the Tang; she died in 790 in the country of Min, in Fujian. She gave rise to a spirit medium cult and performed miracles, which earned her the construction of a temple. She was canonized during the Song. “Biography of Shunyi Furen, the Beneficent and Just Lady,” in Soushen ji (1607: Xu Daozang, no. 1476, 6: 6b–7a). According to the Fengjing zalu, there was a daughter of the Chen family who lived in the subprefecture of Gutian, in the country of Min, during the Dali reign period [766–79] of the Tang. From birth, she had rare gifts: she could predict the future and all her predictions were correct. To play, she liked to cut out butterflies and sparrow-hawks and other animals. She blew charmed water on them, and they could then fly and dance. She fashioned with her teeth a baton one foot long with which she could make cows low and horses whinny; she could also make them run or stand still as she pleased. When she felt like eating, she emptied bushels and casks, but it also happened that she sometimes fasted for days, just as she pleased. She amazed everyone, and not even her parents had power over her. She had not yet reached adulthood when she died. It was then that she took possession of a medium (tongzi) for the purpose of communication. The people of the country appealed to her at times of drought and other calamities and each time her words were efficacious. They thus founded a temple for her and the Song dynasty canonized her as the Beneficent and Just Lady (Shunyi Furen). Many miracles occurred in all periods. Today, her cult is very widespread in the country of the Bamin [the “eight Min,” that is, the whole of Fujian].

The following text adds other elements to this archaic structure. Pregnant, the Lady performed a ritual for rain. She died and appeared as a goddess in order to eliminate a snake demon and to help a woman in childbirth. This is why they insisted on her canonization. “History of the Goddess of the Shunyi Temple,” in Gutian xian zhi (Gazetteer of the District of Gutian) (1710 [1967], 5: 12a–14a). The Shunyi Temple is 30 li east of the district of Gutian, at the place called Linshui. The goddess is named Chen. For generations, her ancestors were

Introduction

5

shamans (wu). Her grandfather was called Yu, her father Chang; her mother’s family name was Ge. She was born during the second year of the Dali reign period [767] of the Tang dynasty and she had supernatural gifts. She married Liu Qi and was several months pregnant when there was a severe drought. She performed a ritual for rain that was immediately efficacious. When she was carrying out her divine procedures and was on the point of death, she uttered the following formula: “After my death, I will save women in danger at the time of childbirth; otherwise I will not be a goddess.” At the time of her death she was twenty-four years old. Her miracles abounded. At Linshui, there was the grotto of the White Snake, whose breath was lethal and spread disease. One day, a person dressed in red and holding a sword captured the snake and cut it into pieces. The people of the country asked her her name. She said: “I am the daughter of Chen Chang of Xiadu (Lower Ford) of Jiangnan.” Then she vanished. They immediately went to Xiadu to make inquiries about her and learned that she had become a divinity. Subsequently, a temple was constructed on the grotto of the White Snake with a pavilion for her to dress up in. At Jianning, there was the daughter-in-law of a certain Chen Qingsou. She was seventeen months pregnant, without giving birth to her child. Suddenly a Lady appeared at her door and said that her name was Chen and that she was an excellent doctor. She asked Chen Qingsou to set up a pavilion to one side, make a hole in the middle, and put his pregnant daughter-in-law in the upper story. She ordered the servants to take sticks and wait in readiness on the floor below. Then [the daughter-in-law] gave birth to a snake three meters long. It fell down through the hole and the servants killed it. To thank her, they offered her gold and cloth, which she would not accept. She only took a handkerchief on which Chen Qingsou had written in his own hand the following eight characters: “Offering of Chen Qingsou to Lady Chen, who assists at childbirth.” Then [Lady Chen] said that she lived at Gutian at such and such a place and that her neighbors were so and so. “If you give me your goodwill,” she said, “please come visit me.” Then she departed and they did not see her again. Later, when Chen Qingsou became prefect of Fuzhou, he remembered this story. He ordered an emissary to pay a visit to the Lady’s house. A neighbor told him that at this place there was only the temple of the Lady Chen, and that she often transformed herself to go save women in the throes of childbirth. When he examined the temple, he saw that the handkerchief was hung in front of her statue. For this reason, Chen Qingsou asked the court to canonize her, and from this time on offerings flowed in without ceasing for a single day. During the Chunyou reign period [1241–53] of the Song she received the title of Ciji Furen: the Lady Who

6

Introduction Is Merciful and Saving. At the temple they bestowed on her the name of Shunyi, Beneficent and Just. During the Ming, Zhang Yining wrote a memorial about her and explained how people had long donated goods to provide for her cult.6

In 1347 the cult was still inscribed on the Register of Sacrifices, as demonstrated by Zhang Yining’s memorial. The literati and officials wrote about it. The temple was enlarged and embellished thanks to the gifts of the faithful. The principles of geomancy were respected. Rituals were performed there. We also learn that there was an illustrated booklet on this subject and that the cult was present in Zhejiang.7 The Lady is compared to the illustrious goddess Mazu. “Zhang Yining’s Memorial on the Shunyi Temple,” in Cuiping ji (Siku quanshu zhenben ed., 4: 48b–50a), and reproduced in the Gutian xian zhi (1710 [1967], ch. 5: 134–35). Thirty li from the town [Gutian] there is the place called Linchuan; a temple there bears the name Shunyi, and the divinity is the Lady Chen. This cult, which was born during the Tang, was canonized during the Song and [the goddess] was given the title of Shunyi Furen, Beneficent and Just Lady. Her divine power spread throughout Fujian and extended as far as Zhejiang. This entire story was related on a stele erected by the prefect Hong Tianxi.8 Under our glorious Yuan dynasty, there was an illustrated booklet on this subject and her [cult] is still inscribed on the Register of Sacrifices. Around 1333, Marshal Li Yunzhong, especially charged with the protection of the region of the Zhedong, came in person to visit the temple, and enthusiastically admired it. Just at that time, work to enlarge it had been undertaken, but not yet completed. In 1341 Chen Sui, a man of the region employed in the prefecture, deploring that the memory [of the story of the goddess] remained incomplete, compiled records about her. He then used them to submit a request that her honorific title be increased. This request was sent to the imperial chancellery, which carefully examined it. While waiting for a decision from his superiors [in the hierarchy], Chen Sui thought that in order to display the true splendor of this canonical story one should start by embellishing the house [of the goddess]. Thereafter he devoted all his efforts to making the temple even more beautiful. He placed himself at the head of all the men of good will and requested the clerk responsible for the inspection of public affairs of the prefecture [to direct the organization of the work]. Those higher and lower [in the hierarchy] thus coming together, each began to compete in generosity by bringing contributions. Having learned of this righteous cause, the great landholders and rich merchants happily adopted it. A religious service was arranged

Introduction

7

to which everyone near and far came to take part and on the occasion of which each and every one eagerly gave presents. A large sum was thus raised, and builders were able to begin work to renovate the temple. They built, going from the exterior to the interior, a pavilion for burning incense, a sanctuary for the twelve divinities, and a temple of happy births. Then they built a ceremonial door and an audience hall, followed by a two-story pavilion for private apartments. There was also a pavilion for dismounting and for [organizing] banquets. The statues were painted and decorated, and all were lacquered in red. The work of the artisans was extremely fine. In front of the temple they built a rock wall in order to protect the head of the dragon, and behind the temple they dug a pond to combat the geomantic influence of the springs.9 They also built a temple for the protection of life to commemorate the virtues of the head of the association. The work that had started in the dinghai year [1342] was completed in the spring of the following year, when the inauguration took place. Its extreme majesty and splendor caused hearts to thrill and eyes to widen. The old people of the region, full of respect, came to look at it, and said to themselves that, decidedly, since there had been temples, there had never been one so beautiful, and that now that there existed such a beautiful place, the gods certainly would not fail to honor it with their presence. From that time on, countless joyous crowds filled the place. It was then that I was asked to write this memorial, and I, Yining, think that the divinities of my country [Fujian] are already well known in the world, such as, for example, the Lady Who Helps and Saves, Shunji, of Putian, whom sailors deem as precious as their own lives, the one to whom they owe everything.10 Her merit to the nation is already great and her extraordinary fame is the subject of exhaustive descriptions. Now the Lady Shunyi is able to overcome calamities and avert disasters, she answers [prayers] with immediate efficacy and her virtue, in relation to the people, how could it be superficial? That is why it is right that she have a place [of worship] and that people like Chen Sui exert themselves, as he did, to build it. That the people did not avoid this work is also highly meritorious. I thus put all this in writing, and I composed the following poem: Contemplating Linshui And this temple so resplendent It is like a jewel Amidst the mountains and waters. When the emperor loves all living creatures The gods manifest their grandeur. When the people pray respectfully How can one not love it! Majestic is this new temple

8

Introduction That dominates Linshui! Like the baby nestled against its mother Are the hearts of men to the goddess. The houses are full of grain The offerings are abundant Gods and men alike rejoice Evil influences are no longer felt No more disease or pain The people are full of joy This cult will last thousands and tens of thousands of years In the service of our enlightened divinity!

Here is another version. The Bodhisattva Guanyin of the South Sea brought about the birth of the Lady so that she would fight against a demon emanation of the Snake constellation, to whom children were offered in sacrifice. She went to Mount Lü in order to study with Master Jiulang, who passed on to her the teaching of the Thunder rituals and those of the Northern Dipper.11 Her family consisted of officials and ritual masters, whose religious observance was tinged with tantric Buddhism. “Biography of Da’nai Furen,” in Sanjiao yuanliu soushen daquan and also in Sanjiao yuanliu shengdi foshuai soushen ji, which gives an almost identical version.12 I will give here only a single translation of these two texts, while noting in brackets the variants of the Soushen ji from the Tanya tang. The fourth Lady Chen lived for generations at the place called Lower Ford in the Luoyuan district in Fuzhou prefecture. Her father was censor and he received the title of steward in the Ministry of the People. Her mother was a Madame Ge, her older brother was Erxiang, and her adopted brother was Haiqing. In the first year of the Jiaxiang period a female snake caused disasters and devoured people. It had chosen for its home a grotto located in the village of Linshui, which was located in the pleasant countryside of Gutian district. The people of the village gave it offerings in order to appease it. Every year on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month they had to buy two children, a boy and a girl, to satisfy its desires. It then ceased to cause harm. At that moment, the Bodhisattva Guanyin was on her way home from a banquet in the South Sea. Suddenly, she saw that a poisonous vapor filled the Fuzhou sky. She then cut off one of her fingernails, which turned into a ray of light that penetrated Old Chen’s wife, Madame Ge, who became pregnant. When she gave birth on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month of the first year of the Dali reign period [766], which was a jiayin year, at the yin hour [that is, between three and five in the morning], there were many favorable omens. A bright light was seen,

Introduction

9

perfume permeated the air around the baby’s body, and the sound of a golden drum was heard near the door, as if a multitude of immortals had come to attend her and present her. That is why she was called Jingu, “she who is presented.”13 Her older brother, Erxiang, had orally received the teaching of the true doctrine of Yoga, which was passed on to him by a divine man.14 These methods enabled him to communicate with the three worlds. In the higher world, he was able to command the celestial generals, and in the lower world the shadow soldiers (yinbing). His magic power was immense and he saved people everywhere. When he came to Linshui village in Gutian, it was the turn of the believer Huang San to preside over the sacrifice [of the children]. In his heart he hated this demon and he came up with a way to stop its evil deeds. He refused to send innocent victims to die in the poisonous mouth of the demon. At the same time, he respectfully requested Erxiang to perform his magic in order to destroy it. However, because at this time Haiqing was drunk, he missed the opportune moment to present his message to Heaven; therefore the celestial soldiers and the shadow soldiers were unable to come to his aid, and Erxiang was breathed on by the poisonous breath of the snake [and Erxiang was injured by the poisonous breath despite all his trouble, as is mentioned in the Soushen ji from the Tanya tang]. Fortunately, there was the divine power of the master Yu: rising up into the sky, he caused a golden bell to fall from the sky in order to protect him. Thanks to the divine wind that spread out around the bell, the demon could not approach, but Erxiang could not get out, either. Jingu was then seventeen years old and she cried over the one who was born of the same breath as herself. She went to the grotto of purity of Mount Lü where the Jade Maidens are masters. The master [Master Jiulang] taught her the exorcistic rituals of the Northern Dipper and the Thunder to destroy the snake’s grotto.15 She rescued her brother and cut the snake into three pieces. The snake was of a type that incorporated the vitalizing essence of the Snake constellation. The magic power born of the breath of the golden bell was thus completely dissipated in the air. How could one kill this snake? One could only destroy its poison. Today, starting on the thirteenth day of the eighth lunar month the House of the Snake is ascendant in the sky and it causes much wind, rain, and hail, which ruin the people’s harvests. It also sends out numerous aquatic demons that are proof of its existence. When the queen of the later Tang [923–36] was in great danger during a difficult childbirth, and her days were numbered, the Lady performed rituals in the palace, and, thanks to this, the queen gave birth to the heir apparent. The ladies in waiting informed the king of this. He was

10

Introduction very happy and conferred on her the title of Great Lady Devoted to the Efficacious Response, Happy and Universal Protector of the Kingdom (Dutian Zhenguo Xianying Chongfu Shunyi Da’nai Furen). A temple was constructed for her at Gutian so that she would prevent the snake from causing harm. The Sage Mother bestowed great benefits on the people and her magic spread throughout the world, particularly for protecting children, both boys and girls, for hastening childbirth, for protecting young children, and for preventing demons from causing harm. At the end of a long period, troubled by her failure to vanquish the snake once and for all, she took an oath, saying: “You are capable of spreading evil, but I can present incense and save the world.” Today, people respectfully recall her story, and they revere her magic, which has many effects. Her father [received the title] of duke (wei xiang), the Sage Mother Ge [received the noble title] of Lady (furen). Her older brother, Chen Erxiang, was appointed duke. Her elder sister [was appointed] Prestigious and Beneficent Lin Jiuniang. Her festival takes place on the ninth day of the ninth month [the date of her festival is not mentioned in the Soushen ji of the Tanya tang]. Her younger sister, who destroyed the demon temple at the mouth of the river, received the title of Third Lady Li (Li San Furen). Her festival takes place on the fifteenth of the eighth month.16 There were also the great sages Zhang, Xiao, Liu, and Lian, who helped to destroy the sanctuary, and also Dongma Shawang, the great General Wuchang, the Sage Mother Who Hastens Births (Cuisheng Shengmu), and the two generals Pochan and Lingtong.

The following text is a sort of synthesis of the different versions. Many new honorific titles of the Lady are cited, among them that of Bixia Yuanjun. There is a reference to the tuotai, “liberation from the womb” / “abortion,” that preceded the ritual for rain. We also learn that there were many texts that recounted the episodes of her mythological great deeds, and that they served as models for carving the bas-reliefs of temples. “Note on Lady Chen,” by Shi Hongbao, in Min zaji (first ed. from the Qing; Shi Hongbao, 19th c. [1985], ch. 4: 73). The Lady Chen, also called Lady Linshui, has temples in every province and every district of the country of Min. It is above all women who make offerings to her. Liang Jilin wrote an essay on withdrawing into monasteries, according to which the Lady was called Jinggu, “She Who Pacifies.”17 She was a native of Gutian district, of the village of Linshui. At the time of king Lin [933–35] of Min, the Lady’s elder brother practiced the “Dao of the Left.”18 He had withdrawn into the mountains where the Lady often

Introduction

11

brought him food. Subsequently, she received a secret Register and a talisman that permitted her to command divinities and demons.19 She went to Yongfu to punish the White Snake demon. King Lin gave her the title of Benevolent and Just Lady, Shunyi Furen; later she disappeared at sea, it is not known where. Xie Jinluan, in his monograph (zhi) of the district of Taiwan, Taiwan xian zhi, says that the Lady was named Jingu. She was a native of Fuzhou. Daughter of Chen Chang, she was born in the second year of the Dali period [767] of the Tang. She married Liu Qi and was several months pregnant when there was a great drought. She “aborted” (tuotai) in order to perform a ritual for rain, and she died at the age of twenty-four.20 Dying, she said, “After my death, I will be a goddess, and I will save pregnant women in distress.” In Jianning, the daughter-in-law of Chen Qingsou was seventeen months pregnant and had not yet given birth. The goddess appeared and saved her; she gave birth to a snake the size of several bushels (dou). At the village of Linshui in Gutian, there was the grotto of the White Snake. Its poisonous breath caused epidemics of plague. One day a villager saw a woman dressed in red cut it in two with her sword. She said, “I am the daughter of Chen Chang of the Lower Ford of Jiangnan.” Then she disappeared. So, they constructed a temple on the site of the White Snake’s grotto and from this time on there have been many miracles. In the middle of the Chunyou period of the Song [1241–53], she received the title of Merciful and Saving Lady Who Accumulates Blessings and Spreads Benevolence (Zhongfu Zhaohui Ciji Furen), and the temple received an honorific plaque with the name Shunyi. Later on, she was further granted the title of Original Lady of the Jasper and Cinnabar Clouds, Sage Mother Celestial Immortal, Azure Spirit of Universal Transformation (Tianxian shengmu qingling puhua Bixia Yuanjun). Many books were engraved in different places that tell the story of Chen Jinggu, for example, the episode of Chen Qingsou’s daughter-in-law that we find in the records of Jianning: at the time of the Song, in the town of Pu, Chen Qingsou’s daughter-in-law had trouble giving birth. The Lady transformed herself and saved her without accepting any gifts in thanks. They asked her what her name was and where she lived. She said, “I come from Gutian and my name is Chen.” Later Chen Qingsou became prefect of Fuzhou. He ordered someone to go to Gutian to make inquiries, and the messenger saw the statue [of the goddess] in the center of the temple. Then they knew that the Lady had transformed herself. Chen then requested the court to canonize her. Today, pregnant women on the verge of giving birth hang up an image of the Lady in their bedrooms. On the day of the baby’s first bath they thank her and burn the image.

12

Introduction These different versions do not tally. The various editions recount any number of extravagant claims such as, for example, at seven years of age the Lady was carried off by the wind, at thirteen she had attained the Dao (the Way), she married a certain Huang of her village, she came to the rescue of King Lin with the help of soldiers, she killed the demon of the Great Ravine with a sword, she took in the Rock-Press demons, and so on. These stories do not make sense and their language is unrefined, although they are used for inscriptions on pillars of temples: one can only laugh at them.

Finally, here is an example of the text of a very recent stele, set up in front of a temple in the south of Taiwan. A carved motif on it also represents the scene described in the text. We may note that the date of birth is different and corresponds to the period of the kingdom of Min. The later theme of the rejection of marriage appears in relation to Guanyin and the figure of Shancai (Sudhana). Finally, the mantic steps performed on the ritual mat correspond to the bugang, the walk on the stars of the Northern Dipper constellation. This time, the master of Mount Lü is Perfected Lord Xu, Xu Sun, and the Celestial Master Chen Shouyuan is presented as a relative of Chen Jinggu. The White Snake and the demon of the Great Ravine are the main characters of the exorcistic combat that cost Chen Jinggu her life. History of Chen Jinggu recounted on a stele set up in front of the Linshui Temple (Linshui gong) of Baihe: “The Transformations of the Isle of the Dragon and Phoenix” (originally, Island of the Female Ducks).21 Chen Jinggu [the Lady of Linshui] was born during the Tang dynasty in the second year of the Tianyou reign period of Emperor Aidi [that is, in 905] on the fifteenth day of the first month, at the auspicious hour chen [between seven and nine in the morning]. They tried to force her to marry, but she would not. That is why Shancai begged the Bodhisattva Guanyin to use her magic power to take her to Mount Lü to study magic. At the end of three years she left Mount Lü. Her master warned her that when she was twenty-four years old she would be in great danger, and he earnestly cautioned her not to use her ritual instruments, read sacred books, or write talismans. In the second year of the Yonghe reign period of the Tang [936], in the seventh month, in the autumn, there was a great drought, the rain failing to arrive.22 The king of Min ordered Chen Shouyuan, the Daoist priest (daoshi) of the Lingbao Temple (Lingbao huang gong), to construct a sacred area (tan) and perform a sacrifice (jiao) to bring rain, but he was unsuccessful.23 Chen Shouyuan then went to beseech Chen Jinggu for help. Chen Jinggu knew that she would be in great danger if she violated the

Introduction

13

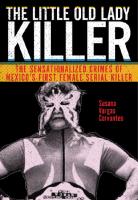

interdiction [of the master of Mount Lü]. And yet she wanted to save the people and she also wished to save her brother and all the other Daoist priests. She therefore went to Bailong jiang [White Dragon River, today under Nantai Bridge in Fuzhou]. She placed a mat on the water, unbound her hair, and put on her magician’s headdress and skirt [see Figure I.1]. In her left hand she held a horn with divine power, and in her right hand her ritual sword. Then she traced out mantic steps on the mat placed directly on the water, while dancing with her sword and blowing on the horn; she danced on the constellation of the Northern Dipper in order to perform the true magic of Mount Lü. She pronounced secret formulas, performed the

f i gur e I.1. Chen Jinggu dancing for rain, Linshui Temple, Baihe, Taiwan. Photo Jean-Charles Berthier.

14

Introduction ritual, and wrote Thunder talismans in order to transform the sky. Then she ordered Great Guardian Wang to go immediately to the Dragon King of the Four Seas in order that he might cause rain to fall. The Dragon King knew that the Great Guardian brought an order from Master Perfected Lord Xu.24 Immediately, black clouds veiled the brightness of the sun, a violent wind sprang up, thunder, lightning, and storm clouds swiftly arrived, and a heavy, beneficial rain fell. When Chen Jinggu was about to conclude her ritual, take up her mat and return to the riverbank, the demon of the Great Ravine and the White Snake, who had concealed themselves in order to kill her, took hold of the mat and pulled it into the water. The master of rituals [Fazhu, Perfected Lord Xu], quickly flew to the top of the mountain and, by means of his magic vision, looked into the distance. He took three stones and threw them into the air. They turned into three female ducks able to dive into the water. They seized three corners of the mat and pulled it back to the surface of the water, and, so that it would not float away with the current, they turned it into an island, which was called Duck Island.25 On the fifteenth of the eighth month of that year, at a favorable hour, in Fujian, at Gutian, Chen Jinggu attained the Dao. On three occasions she received an honorific title. Right up to the present day people continue to burn incense for her.

All these different sources provide much information about the cult of Chen Jinggu. We learn that it was shared between two places in the country of Min, Fuzhou and Gutian, where its founding temple is located, and that it also existed in Zhejiang. The key elements of it are the battle against a snake—astral breath or harmful demon—and Chen Jinggu’s apprenticeship at Mount Lü with the ritual masters, Jiulang and Perfected Lord Xu, who pass on to her, above all, the Thunder arts and those of the Northern Dipper. She died while performing the ritual for rain, after having tuotai and after taking a vow to help women. Her family was divided between ritual tasks—shamanic, Daoist, or tantric—and official duties. Finally, according to some versions, Nanhai Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of the South Sea, is said to have miraculously caused her birth so that she would eliminate the snake demon of the country of Min. The theme of rejecting marriage is also sketched. In short, we learn between the lines what the ritual tradition of the Pure and Perspicacious Tradition of Mount Lü (Jingming Lü Shan pai) linked to Mount Lü consists of, which recalls in many ways Mount Lu in Jiangxi, the source of the Thunder ritual arts. We understand in the end that other sources, of another nature, exist in relation to this cult.

Introduction

15

There is in fact an entire literature of pious books (shanshu) emanating from the temples, such as the Da’nai lingjing and the Yulin Shunyi du tuochan ruo zhenjing of Linshui Palace in Gutian, and the Sannai jing.26 These works relate the story of the Lady and present the figures of her pantheon. They likewise provide magic formulas, talismans, and ritual elements. A song in the storyteller style, Furen changci, and a play in twelve scenes, Chen Da’nai tuotai, complete this set (see Ye Mingsheng, 1995, 1996; Ye Mingsheng and Wu Naiyu, 1997; Ye Mingsheng, 2000; Baptandier, 2002, (2008).27 The play, which was banned for many years in the twentieth century as “superstitious” (mixin), dramatizes the very core of the myths of Chen Jinggu: the ritual for rain that required her to tuotai and at the end of which she died. According to a Daoist master in Fujian, this play contains all the rituals distinctive of this tradition. What then is the Jingming Lü Shan pai? And first of all, where is the mysterious Mount Lü located?

Mount Lü Mount Lü, the Portal Mountain that is also called Mount Guangning, is in Liaoning province in Dongbei (Manchuria), in the City of the North, Beizhen, to the northeast of Jinzhou and to the south of Fuxin. Its highest point is Pine Peak. Emperor Shun (2257–2208 b.c.) is said to have given it the name of Youzhou when he divided the empire into twelve parts. It was only under the Sui (581 [589]–618) that this region took the name Beizhen, the “City of the North.” At the very top of a peak was found a statue of the immortal Lü Dongbin (see Cihai zidian, Yiwu Lü Shan, vol. 5). The name Youzhou recalls the Dark Capital (Youdu), region of the Shadows, where the souls of the dead return. Tao Hongjing locates the “borders of the north” (beifeng) at the northern extreme of the Liaodong peninsula in Liaoning province, at the frontier of the country. The Dark Warrior (Xuanwu), “ancestor” of Xuantian Shangdi (High God of the Dark Heaven), rules over this place (Mollier, 1997). Beizhen, located in Dongbei, is a major site of shamanism, as the full name of the mountain indicates: Yiwu Lü Shan, “Mount Lü of the Shaman Healers.” This feature of Mount Lü and the practices that are associated with it were already well known in the country of Min, as the Daoist master of Fujian, Bai Yuchan, attests.28 It would seem that at present there is still a temple on the top of the mountain, that people still practice the arts of long

16

Introduction

life there, and that a connection is, perhaps, maintained between Liaoning and the south of the country. In 1998, a Daoist woman of Liaoning, who had studied with a master at Mount Lü, was living at White Cloud Temple in the Wuyi Mountains, the sacred mountains of Fujian, where she continued her self-discipline. Her Daoist journey had taken her from Liaoning to Fujian. It is undoubtedly for this reason that a mythic Mount Lü imbued with the same symbolism was imagined in the country of Min in Fuzhou. It is precisely situated, in accordance with the names of real places, for example, Longtan huo, Tianning Temple, Diaolong tai, which are said to be vestiges of Mount Lü, located not far from Black Stone Mountain (Wushi Shan), also called Min Shan, high place of Min (see Fuzhou fu zhi, 1967: 93, 89, 95; Wang Yingshan, 1831 [1967]: 91). The present-day inhabitants of Fuzhou can still point out this Mount Lü in the Min River, at the place called Goulong tai, near the old bridge that links Nantai Island, where Xiadu is found, to the town. Fuzhou Lü Shan wenhua, a work published in 1998, glosses all of these points and locates the different places of the itinerary covered by the Mount Lü boat on its way to the Ritual Academy (Da fayuan) (see Lin Xiangcai, 1998). The Mount Lü of the myths of Chen Jinggu is thus a magic mountain. It is said to have been transported by its ritual masters to the bottom of the Min River, at the place called Longtan jiao, at the Upper Ford of Fuzhou, very close to Chen Jinggu’s birthplace at the Lower Ford, Xiadu.29 Moreover, the road that runs along the bank is also called Longtan jiao. Perfected Lord Xu is said to have been its master and it was in the grotto of this Ritual Academy that he is said to have taught his disciple Chen Jinggu. Access to it was by means of a magic boat at the end of a shamanic journey. Although it is thus situated in the actual geography of Fujian, this Mount Lü is neither visible nor accessible to the common herd. On the other hand, there is on Nantai Island a temple called Mount Lü Ritual Academy, which has just been restored. A small Chen Jinggu temple has also recently been rebuilt overlooking the site. Mount Lü goes back to this therapeutic tradition—Yiwu Lü Shan—of Liaoning, while also strongly evoking many ritual aspects characteristic of the neighboring Mount Lu (Lu Shan) in Jiangxi, where Xu Sun lived in the past. Xu Sun is said to have been in contact with the Old Mother (Laomu), protector divinity of women, rightly linked to Mount Lu, where a tradition of female shaman healers is said to have evolved.30 The first altar of the sanctuary of Mount Lu was built in 731, which makes it almost contemporaneous with Chen Jinggu’s first temple (792). This mountain welcomed

Introduction

17

many Daoist masters who were related to the Thunder magic techniques, among them Bai Yuchan himself, the uncontested master of the tradition of the Thunder rites in Fujian in the thirteenth century.31 The guardian of Mount Lu, Envoy of the Inquisition of the Nine Heavens (Jiutian caifang shizhe), who was mentioned in the sources cited above, is supposed to protect the world from “perverse” cults. In fact, this figure is also sometimes associated with Chen Jinggu, and in some temples in Fujian the two of them are represented sitting side by side, like a sort of exorcistic couple.32 Furthermore, a tradition has it that there is a female ritual line at Mount Lü, just as there is at Mount Lu. Chen Jinggu is said to have been taught there, this time by the Queen Mother (Wangmu).33 According to the legends, she later created around her a community of female shamans, some of whom still figure as divinities in her temples today. We should note that there is also a Dragon-Tiger Mountain (Longhu Shan) in Jiangxi province, a major site of the Celestial Master successors of Zhang Daoling. Zhang Daoling founded the movement of the Celestial Masters when he received a revelation from Laojun, the divinized Laozi (see Seidel, 1969). This hereditary lineage, animated by the power of the Orthodox Unity, Zhengyi, continues to this day, and with it the liturgical tradition of local communities (see Schipper, 1982b; and Robinet, 1976). According to Saso, in Taiwan one would associate the “Portal Mountain” (Lü Shan) with the Gate of Hell, site of the cosmos through which demons attack the living. This point clearly refers back to the exorcistic tradition of the ritual line of this name, Mount Lü sect (Lü Shan pai), that the ritual masters (fashi) trace themselves back to. We shall see that it likewise recalls the Sovereign of the Azure Clouds (Bixia Yuanjun)—the daughter of the Eastern Peak—aspect of Chen Jinggu, who received the same canonical title. the mount lü sect (lü shan pai)

This school, or line, of the Three Ladies (Sannai pai) has been attested to since the Tang. From that era down to the present day this ritual tradition was syncretically forged by grafting borrowings from different branches of Daoism and esoteric Buddhism onto a local shamanic or spirit medium substrate.34 Thus was born the Pure and Perspicacious Three Ladies of Mount Lü sect (Jingming Lü Shan Sannai pai), considered to be both a branch of the Zhengyi sect (Zhengyi pai) of the Celestial Masters and a branch of the Jingming sect (Jingming pai), the tradition of filial piety (Xiao dao), of which Xu Sun was considered to be master.35 Moreover, we shall see that this theme

18

Introduction

plays a very important part in the legend of Chen Jinggu, to whom Xu Sun, here the master of Mount Lü, is said to have passed on his teachings. Xu Sun was also a celebrated exorcist of dragons and snakes. To capture them, he used techniques linked to qigong practices known for their efficacy. Chen Jinggu, as we shall see, herself counterpart and subduer of the White Snake of her legend, shares with him this structural trait. Xu Sun is also credited as the founder and source of the Thunder ritual arts (leifa), which incorporate techniques distinctive to internal alchemy (Daofa huiyuan, Daozang no. 1220).36 The rituals of the Sannai sect (Sannai pai) based on the metaphor of the Five Camps—the five directions of the cosmos, the five elements, and the five organs of the human body—integrate the elements of this ancient tradition, called for this reason the “Five Thunders” (wu lei). All of this connects the Sannai sect to other ritual traditions, above all to the Shenxiao, the Divine Empyrean, founded by Lin Lingsu (1076–1120), a native of Wenzhou in Zhejiang and Daoist at the court of Emperor Huizong of the Song. The history of the Shenxiao is recorded in the “Formulary for the Transmission of Scriptures According to the Patriarchs of the Most Exalted Divine Empyrean” (Gaoshang shenxiao zongshi shou jing shi, HY 1272) according to which the Classic of Salvation (Duren jing) was revealed during the Song dynasty (Boltz, 1987).37 Emperor Huizong (1082–1135) is said to have received the mandate of heaven to carry out this mission of saving humanity. As Boltz demonstrates: “Designed to introduce the rudiments of the Shen-hsiao reenactment of the Ling-pao revelation, the treatise supplies the essential cosmological diagrams, talismanic inscriptions, sacred recitations, and lengthy registers of the celestial bureaucracy.” Comparable visual aids are to be found in the 12 ch. HY 1209 Gaoshang shenxiao zishu dafa, “Great Rites in the Purple Script of the Most Exalted Divine Empyrean” (Boltz, 1987: 27). According to Saso (1978a: 61), the masters of the Sannai Lü Shan pai were, moreover, initiated in accordance with the protocol of the Shenxiao, which integrates rites similar to internal alchemy and the rites of the Northern Dipper (Beidou). The local tradition of the Mount Lü sect is in fact well known for its talismans, mudras, and the ritual use of diagrams, for instance, the diagram of the trigrams, as we shall soon see (see Chapter 2). This same text also contains the codes of the liandu ritual, “Salvation through refinement or transmutation,” a funerary rite that includes a contemplative version, as well as a great number of therapeutic principles of the rites of the Five Thunders (wu lei).38 Theoretically, the Sannai tradition only

Introduction

19

carries out rituals intended for the living. No funerary ritual belongs to it in its own right. However, the legends of Chen Jinggu show her frequently performing the liandu ritual—above all for her own son. Today, many ritual specialists (fashi) tracing themselves back to her claim to carry it out, and they possess the texts for it. The Sannai pai is likewise close to the Qingwei, “Clarified Tenuity,” sometimes considered to be one of the names of the Shenxiao.39 The Qingwei is one of the best known traditions in the domain of the Thunder rites, having incorporated the legacy of the diagrams and the mandalas of tantric Buddhism for repelling demons.40 In both cases, these names refer to the central region of the empyrean of the cosmos where the Great Sovereign of Long Life (Changsheng Dadi) dwells, whom the masters of the Mount Lü sect also invoke (Boltz, 1987: 27; Baptandier, 1994b; Baptandier, 1996a). The same primordial breath that is said to have formed the texts of the Lingbao (Marvelous Jewel) is said to have condensed to form the sacred writings and Thunder talismans that are characteristic of the Qingwei (Boltz, 1987: 39). The Lingbao (Marvelous Treasure or Jewel, or Magic Treasure, or Numinous Treasure) is a corpus of texts that constitutes the second section, called “cavern” (dong), of the first Daoist Canon, compiled by Lu Xiujing (406–77). The new Lingbao scriptures attempted to integrate Buddhism through a synthesis at the liturgical level with the Daoist ritual traditions of the south (see Zürcher, 1980). Lingbao is an ancient term for medium or shaman (see Kaltenmark, 1960). According to Bokenkamp: They are thus the first Taoist scriptures to incorporate and redefine Buddhist beliefs, practices, and even portions of Buddhist scripture. They do this quite openly, positing the temporal priority and spiritual superiority of their message against any charge of plagiarism. The very name of the scriptures (ling, “spirit-endowed,” representing the heavens, and yang, joined to bao, “jewel,” representing Earth and yin) refers to the claim that these scriptures are translations of spirit-texts that emerged at the origin of all things when the breaths of the Tao separated into the two principles of yin and yang, thus giving the Lingbao texts priority over texts composed later. (Quoted in Little, 2000: 18)

In addition to its own patriarchs, many transcendent beings were associated with this tradition. As Boltz put it: “There was no divine worthy of any significance who was not given a seat within the ranks of ch’ing wei [Qingwei]” (Boltz, 1987: 39). At the origin of the tradition of the Qingwei we also find a woman called Zu Yuanjun, Zu Shu (fl. 889–904), whose

20

Introduction

story closely resembles Chen Jinggu’s: extraordinary birth, leaving home to receive a ritual education, healer and Daoist, but also cosmic power astride a dragon. She is likewise said to have been taught by female divinities, such as Lady Wen, and later by Lingguan Mu.41 Finally, in the legend the relationship between Chen Jinggu and the Daoist priest (daoshi) Chen Shouyuan is significant. This is because Chen Shouyuan was historically close to the Daoist Tan Zixiao (d. 973), one of the founders of the Tianxin zhengfa, “Correct Rites of the Celestial Heart,” which was very popular in the Song dynasty. This suggests a relation between the tradition of Chen Jinggu and the Tianxin zhengfa.42 The ritual masters insist, moreover, on this ritual relationship between the Mount Lü sect and the Tianxin zhengfa. They say that they are two branches of a single ritual tree, and their texts bear this out.43 The tradition of the Tianxin zhengfa also comes from Jiangxi, in particular, according to some sources, from Mount Huagai, where Rao Dongtian is said to have discovered sacred texts (in 994) that he could not decipher. He is said to have sought help from divine beings in order to understand these writings from the “Heart of Heaven.” On the other hand, other sources make Zhang Daoling (second century) the true founder of this tradition. According to Boltz (1987: 33–34), the earliest corpus we have of the therapeutic rites of the Tianxin zhengfa dates from 1116, and was compiled by the Daoist master Yuan Miaozong (fl. 1086–1116), in order to add it to the compilation of the Daoist Canon (Daozang) ordered by Huizong. Yuan brought with him the ten chapters of the Taishang zhuguo jiumin zongzhen biyao (Essentials on Assembling the Perfected of the Most High for the Relief of the State and Deliverance of the People), which contains within it a manual of talismanic applications entitled Shangqing beiji Tianxin zhengfa (Correct Rites of the Celestial Heart from the Northern Bourne of Shangqing).44 According to Yuan, the origin of the rites of the Tianxin was in fact the far north of the celestial empyrean (Boltz, 1987: 33–34). We shall see that the myths of Chen Jinggu constantly link it to this direction. Most of the materials codified by Yuan were later re-edited by Deng Yougong (1210–79) in two works.45 According to these texts, practitioners, divinities, and demons are all considered to be subjects of the Bureau of Exorcism (Quxie yuan), the therapeutic domain of the Tianxin. Later on, the origin of the Tianxin was located on Mount Heming (Heming Shan) in Sichuan, where Zhang Daoling is said to have received these same revelations. The principal feature of this tradition consists of three talismans of the

Introduction

21

“three luminaries” (sanguang): the sun, the moon, and the stars (Baptandier, 1994b: 59–92).46 Zhenwu and Tiangang are the spirits of the Northern Dipper; they purge humanity of all the demons that infest it. In addition, the practitioners of the Tianxin zhengfa are known for their expertise in the exorcisms of the spirits that cause various mental troubles, in particular those that induce possession by seductive succubi. As Boltz notes (1987: 33–38), many novels relate stories of this sort, in particular Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan), the Romance of the Demon Slayer Zhong Kui (Zhong Kui zhuogui zhuan), and the Pacification of the Demons (Pingyao zhuan).47 The Linshui pingyao zhuan (Pacification of the Demons of Linshui), which will occupy us henceforth, is also such an example.

The Linshui pingyao (Pacification of the Demons of Linshui) the

LINSHUI PINGYAO :

a novel?

There is a text that recounts the life, great deeds, and divinization of Chen Jinggu and that differs from all those we have just examined. It is the Linshui pingyao, “Linshui Pacifies the Demons” or “Pacification of the Demons of Linshui.” The Linshui pingyao stands out from the other sources, above all by its length: it consists of four parts (juan) and seventeen chapters (hui). I have two editions of this work: the older is the lithographic edition of the Xiamen huiwen tang that was given to me by an antiquary in Beigang, in Taiwan. In this edition, the text is classified into “records,” “monographs,” and “biographic notes.” At the beginning of each part are illustrations. The other edition comes from Taizhong, in Taiwan. It was published by Ruicheng shuju, which issued the work again in the 1980s. K. M. Schipper was the first to give me a copy. The work is entitled Linshui pingyao. This edition bears no trace of the division into juan, but it preserves the seventeen chapters in their entirety. These two editions are essentially identical. In the Ruicheng edition, the illustrations are reduced to four small images, reproduced on the same page. These images illustrate the first juan of the Xiamen huiwen tang, which may have served as the basis for the Ruicheng edition. The Ruicheng editions classify this text as an “old vernacular novel” (guben tongsu xiaoshuo). There is no mention of the author’s name. In its form, the text resembles similar books that trace the great deeds of other divinities such as Guanyin in Nanhai Guanyin quan zhuan, or Mazu in the Tianfei niangma zhuan. Written in the vernacular (baihua) in prose, this style of work first appeared around the sixteenth century. These stories

22

Introduction

probably came from the baojuan, hagiographic texts containing liturgical parts and homilies, from the tradition of the bards and storytellers, who told the story of the divinities, and from the theater, dramatizing those episodes of the gods’ myths suitable for performance during their festivals.48 The steles set up in front of the temples, from which the faithful make rubbings, already provided a basic version of the founding myth. The Linshui pingyao therefore appears as a juxtaposition of episodes of various stories, of sketches that at first glance seem to have no direct relation to each other, or, at the very least, each of which could in practice stand independently of the others. Thus, it constantly skips from one story to another with no preliminary transition, except for the habitual phrase of the storytellers: “That is over, we will speak of it no more. Let us now turn to . . .” (Chuan shu buti. Qie shuo . . . ). In fact, it is precisely in this apparent incoherence that the readers recognize the authenticity of the text. Thus, during my first stay in Taiwan (in 1980), the episodes of the story of Chen Jinggu were adapted for television in the form of a serial. For the occasion, the subject was turned into a novel, and a logic, a continuity, was introduced into the episodes, which was necessary to hold the audience in suspense. But this version was criticized very severely by Chen Jinggu’s followers, as well as by the ritual masters who smiled caustically and said that “it was not her true story,” that it was not “like in the Linshui pingyao.” The fact is that through the apparent chopping of the text into small pieces, into a mosaic of stories, its readers are able to discern a more fundamental symbolic unity that lays the foundation of this cult. This text is not a “novel” about Chen Jinggu. Rather, it gathers together the mythic episodes that establish the cult and the ritual of the Mount Lü sect. It is also from this angle that I tried to analyze it, listening to the episodes, the stories, and the words as if I were listening to dream stories, memories, or fantasies. In particular, this was my method of approaching the powerful language of the Linshui pingyao. It seemed to me that this was the way to bring its true inspiration to light. That the Linshui pingyao is so confused in regard to dates is understandable if we consider the absence of unity of composition. The first episode, that of the construction of Luoyang Bridge, begins at the time of the troubles caused by the Huangchao Rebellion (874–84), during the Tang dynasty. No precise date is given for Chen Jinggu’s birth, unless we consider that her miraculous conception through the instrumentality of Guanyin is said to have taken place at the end of this episode. There is a Hokkienese song that tells

Introduction

23

this very famous story of the construction of the bridge, the Cai Duan zao Luoyang qiao ge, which may have inspired the author of the Linshui pingyao.49 The final sentence of the Linshui pingyao situates the time of the narration in the Zhengtong years of the Ming (1436–50), under the emperor Yingzong, that is, five hundred years after the events of the story, which comes to an end in the Changxing reign period of the Tang (930–34), under the emperor Mingzong. It is likely that the oral versions of the legend circulated and spread more and more widely, until the episodes were finally written down and printed in the form first of manuscripts and lithographies, and then published. For reasons of internal logic, the texts of the editions I have appear to date, in their definitive versions, to the beginning of the Qing.50 The copies I have were probably published at the beginning of the twentieth century. A delegation from the Phoenix Hall of the Limitless Heaven (Wujitian Feng tang) of Taizhong made a pilgrimage to Fuzhou in 1993, bringing with them a copy of the Linshui pingyao zhuan, which had been paid for by gifts from the faithful. This new edition is presented as a pious work conferring merit on the generous donors. This process probably does not differ greatly from those that gave birth to the first editions of the work. In 1993, a conference entitled Research on the Culture of Chen Jinggu (Chen Jinggu wenhua yanjiu) brought together in Fuzhou researchers from different bureaus of religion, of culture, of local monographs, and historians from Fujian and Taiwan, in order to trace the history of this cult. This accompanied the cult’s official rehabilitation, after years of prohibition as “superstition” (mixin) in the People’s Republic of China. Thus, this conference, whose subject was the cult of Chen Jinggu, transformed these “superstitious” beliefs into orthodox culture (wenhua). The proceedings of the conference were published in Fuzhou and cite different sources (Zhuang Kongshao, 1993: 7). This process is comparable to what occurred at the time when Zhang Yining was requested to write his memorial. the shaping of the linshui pingyao: emancipation of a local cult

Due to the publication of the Linshui pingyao, this cult of the country of Min was brought to the attention of a larger public, going beyond the place and time of its origin. Thereafter, Shi Hongbao had no difficulty criticizing texts of this genre for their “lack of literary skill.” Éliasberg also notes in her study of the Zhong Kui zhuogui zhuan this feature of containing almost

24

Introduction

no literary and historical allusions, citations, or poems. In fact, these are texts of a very special kind, not lacking rigor, as the author of the Min zaji suggests, but conforming to another logic: that of promoting a cultic ensemble that is already in and of itself a historic, local, literary, and cultural point of reference. This is a significant fact for the political implications of the process of the cult’s literary evolution. In fact, the freeing of the cult from a local community (economic and political structure) does not happen without a certain assertion of the power of this community. This is demonstrated by Zhang Yining’s description of the first official construction of the temple. It is likewise a significant fact for the subject of this cult (the feminine), for its adepts (women), and for its syncretic ritual tradition. In his book on the legend of Miaoshan, Dudbridge points out the sweeping influence exerted by this type of work intended for mass distribution. He accounts for it as follows: “Their undeniable importance lay in their normative force extending widely but unevenly through the whole spread of society, and in their simultaneous reflection of values and preoccupations common to the public at large, as they strove for the appeal which would guarantee their circulation and survival” (Dudbridge, 1978: 21). If we trust the example of the Linshui pingyao, it seems that the interest that is evinced for them is linked to the themes characteristic of the specific cults of which they are the reflection, rather than to a deliberate attempt on the part of their author(s) to capture the attention of the largest possible audience. And therein lies the answer to Éliasberg’s question, why today in the People’s Republic of China the Zhong Kui zhuogui zhuan is not accepted “as entertainment, a charming and picturesque fantasy that offers relaxation and escapism to the spirit” (Éliasberg, 1976: 149). It is precisely because it is not a matter of “entertainment” but of religion and myths, the fabric of which forms the web of local cultural manifestations of unconscious representations. Moreover, if for good reason they do not accept the Zhong Kui zhuogui zhuan as entertainment, they are not mistaken, either, about its true nature, which today continues to exercise an influence in a different context, as Éliasberg also shows: Despite the radical upheavals and transformations brought by the revolution, the traditional figure of the Demon Slayer still remains alive. In a letter (which appears to be authentic) to his wife on 8 July 1966, following the campaign led by Lin Biao to heighten his cult of personality in the 1960s, did Mao Zedong not say that he had become the Zhong Kui of the communist party? (Éliasberg, 1976: 149)

Introduction

25

The theme of the feminine in Chinese religion, which I discussed earlier, was particularly important in the Tang, when the cult was born. Thus it was inevitably fundamental to this movement promoting popular cults. Room was therefore made for it in the Linshui pingyao. That is why this work appears to me as the necessary link between the origin of this cult and its present observance, as I was able to trace it out in Taiwan and Fujian. the

LINSHUI PINGYAO ZHUAN :

a myth of the kingdom of min