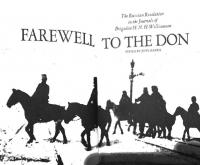

The February Revolution in the Oblast of the Don Voisko

397 99 34MB

English Pages [171] Year 1967

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

Duke University Library The use of this thesis is subject to the usual restrictions that govern the use of manuscript material.

Reproduction or quotation

THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION IN THE OBLAST OF THE DON VOISKO

of the text is permitted only upon written authorization from the author of the thesis and from the academic department by which it

fey

was accepted. Proper acknowledgment must be given in all printed references or quotations. POIM 411

IM

Bruce William Menning

11-44

Department of History IXike University

^ / 'FT? Approved:

Warden Lerner, Supervisor

MAXIMA A /AMM A/ I).A

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Duke University 1967

~7e. /P. fi. m. Ms*-'?? /

orfd

od

8„Jtb*>0o«

rodio ,,s

•**" "™ «» «* o3 so.****, «. sdl

I

popular usage through other forms of transliteration (e.g., Cossack, Bolshevik, soviet, and oblast). B. W. M.

(iv)

CONTENTS

PREFACE INTRODUCTION I.

AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE OBLAST OF THE DON VOISKO

II.

THE OBLAST OF THE DON VOISKO ON THE EVE OF REVOLUTION

III.

THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION IN THE OBLAST OF THE DON VOISKO Revolution in Novocherkassk, 38 The Peasant Revolution, 49 Revolution in Rostov, 58

IV.

CONCLUSIONS APPENDIX

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

(V)

TO TBAtlE 0 iJlT TO

rQ1"

IH HMIJftJO MA

.1 .

3HT tor

aWDx. ujohoc

.vi^

yiw HoouEifl asiata

THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION IN THE OBLAST OF THE DON VOISKO

OflBIOV WK! F.HT HO TBA.vl'I? < ?IKT WT W • rnu«

'FTAUH'fflM HHT

INTRODUCTION

Almost Immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in October, 1917* the Oblast of the Don Voisko,

located in south

Russia between the Black and Caspian Seas, became one of the centers of organized resistance to the newly established Soviet Government.

This resistance at first took the form of a native

Don Cossack movement under the strongly anti-Bolshevik Cossack Ataman, Aleksei Maksimovich Kaledin.

Kaledin's position was

reinforced when a number of ex-Tsarist army officers, led by Generals M. V. Alekseev, L. G. Kornilov, and A. I. Denikin, migrated to the Don to raise a counter-revolutionary army of volunteers.

Above all, these officers needed time to recruit,

organize, and equip what would later become the Volunteer Army. They hoped that the inhabitants of the Don, particularly the Don Cossacks, would provide the necessary protection until the Volunteer Army was strong enough to take the offensive against 2 the Soviet Government in the north. 1 Oblast of the Don Voisko means literally District or 'erritory of the Don Host. The name Is retained for reasons of ocuracy and frequency of appearance In printed sources, but will lso be referred to variously as the Don Territory, the Don iblast, or simply the Don. See map in appendix. 2. For an accurate and lengthy description of the origins (2)

3 By the beginning of December, 1917, the counter-revolu tionary stirrings in the Don were strong enough to warrant the attention of the Soviet Government or Council of People's Commissars in Petrograd.

While the problem of negotiating a

oeparate peace with the Central Powers loomed large on .the horizon, the Bolsheviks could not ignore the threat to their regime posed from the south.

Accordingly, V. I. Lenin, the

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, dispatched Commissar V. A. Antonov-Ovseenko to Kharkov in command of the first Soviet campaign of the Civil War in south Russia.

Against

the combined forces of the Don Cossacks and the Volunteer Army, Antonov-Ovseenko possessed a motley collection of old army units, revolutionary sailors, volunteers, and units composed of hastily recruited and trained factory workers.

In January, 1918, the

young Soviet Commander launched these forces, collectively known as Red Guards, in a three-pronged assault on the Don Territory.1 Contrary to the expectations of Ataman Kaledin and the counter-revolutionary Generals, the inhabitants of the Don provided little resistance to the advancing Bolshevik detach ments.

Internal dissension, disaffection, and popular unrest

caused resistance to melt away in the face of the Bolshevik of the counter-revolution in south Russia, see George A. Brinkley, The Volunteer Army and Allied Intervention in South Russia (NoUre Bame, Indiana: "University of Notre Dame Press, 19bb), pp. 3-36. 1 A concise description of the Soviet campaign is con tained in the standard early Soviet history of the Russian Civil War by A. S. Bubnov, S. S. Kamenev, and R. P. Eideman (eds.), Grazhdanskaia voina, 1918-1921 (3 v°ls.j Moscow: Gosizdat, "Voennyi Vestnik," 19^8-1930), III, 44-4u.

attack.

4 Large numbers of non-Cossacks l i v i n g i n t h e Don O b l a s t

went o v e r t o t h e s i d e of t h e B o l s h e v i k s , and t h e Cossacks, p e r p l e x e d by t h e b e h a v i o r of t h e non-Cossacks and divided among themselves, failed to present a united front against invasion. The V o l u n t e e r Army, t o o weak t o r e s i s t t h e S o v i e t s a l o n e , was f o r c e d t o l e a v e t h e Don and t o embark on a h a r s h w i n t e r march, the

I c y Campaign," i n t h e Kuban s t e p p e s . 1

I t was n o t u n t i l

a f t e r t h e f o l l o w i n g summer t h a t t h i s Army, i t s r a n k s decimated cy t h e h a r d s h i p s of t h e p r e v i o u s w i n t e r , was a b l e t o resume a c t i v e o p e r a t i o n s a g a i n s t t h e S o v i e t Government.

However, by

m i d - 1 9 1 8 , t h e S o v i e t s had begun t o o r g a n i z e t h e i r m i l i t a r y f o r c e s more e f f e c t i v e l y , and t h e V o l u n t e e r Army now f a c e d Leon T r o t s k i i ' s Red Army i n s t e a d of t h e p r e v i o u s l o o s e l y organized Red Guard d e t a c h m e n t s .

E a r l y S o v i e t v i c t o r y i n t h e Don had

t h e r e f o r e e n a b l e d t h e B o l s h e v i k s t o s t r e n g t h e n and t o c o n s o l i d a t e t h e i r m i l i t a r y p o s i t i o n with l i t t l e o r no i n t e r f e r e n c e from t h e V o l u n t e e r Army. I n view of t h i s development, t h e f a i l u r e of t h e c o u n t e r r e v o l u t i o n i n t h e Don a t t h e beginning of 1918 was of g r e a t i m p o r t a n c e i n t h e R u s s i a n C i v i l War.

Both t h e Whites, a s t h e

c o u n t e r - r e v o l u t i o n a r i e s were c a l l e d , and t h e Bolsheviks seemed aware of t h e c h i e f c a u s e s of White d e f e a t .

One of t h e most

1 . One of t h e b e s t secondary s o u r c e s f o r t h e e a r l y cam p a i g n s i n South R u s s i a i s David Footman, C i v i l War I n Russia (London: F a b e r and F a b e r , 1 9 6 1 ) , PP« 4 6 - 4 7 , b 2 - 5 9 . F o r t h e Cossack s i d e of t h e s t o r y s e e , S . V. Denisov, Zap!s k i : e r a z h d a n s k a i a voina na i u g e R o s s i i , 1918-1919 66* ( C o n s t a n t i n o p l e : Tzdanle a v t o r a , 1 9 ^ l T 7 P p 7 " 1 / - 3 0 . T f i F T T u M r T W r i t o r y was s o u t h e a s t of t h e Don O b l a s t .

^ V,. t [ iBBXdO noa

(1.r

t-J • •• ?r,:! '•'• 1C

oel£d|

.doiBin isJo *

«• '

£t 8901©"J

1 --i'-

bed noG edit at

.1- Jof« Jg

•

ti

©tfebXlosaoo otf

.

2 sei

"1

TS

•xcl Jq90X9 s g s u s n s l rts , e ' '

fstrfw !© ! £ • j f l

W

.

l o Y l l S f r i 3"sol aj.OBSS < :

' •

I J J T IICFQFL

.

BOASLIVILLC

O

J -C'L:

>

LIT

% ®

.

OF ,11

PP« 57-59. 2.

Ibid., p. 59.

•jo 90c

r.

t

t

•

hfffi c, 1 rnonoo#

*

«

,

Xs-to-wmmoo iccem s

.

: I

22 industrial and mining complex developed in the Donets Basin, and quite naturally some of this development spilled over into the Don Oblast. As in many of the regions of European Russia, economic growth spurred the building of railroads in the Don. In view of the difficulty of navigating the Don River, the 2,310 versts1 of railroad built in the Don became an important means of transporting bulk goods.

Although the lines were designed chiefly to

.•neei: the needs of the Donets Basin and the agricultural area of south Russia as a whole, they did provide the Don with the first bones of a rudimentary transportation skeleton.

The most im

portant of the railroads was a north-south line which connected Rostov and Taganrog with Voronezh in the north.

Of nearly

equal importance was the line that joined the Donets Basin in the west with Tsaritsyn (present-day Volgograd), an important industrial and port city on the Volga just east of the Don 2 Territory. Except for the railroads, transportation and communica tion in the Don were generally poor.

Telephones were non

existent, and the telegraph followed the major rail lines.

In

the winter or in periods of heavy rainfall, many of the main roads became impassable for wheeled vehicles.

The result was

that individual stanitsas and peasant villages, unless by chance located near a railroad, were isolated much of the time from the

1. mile.

Verst:

a measurement of distance, equal to .6629 of a

2. Dobrynin, Bor'ba s Bol'shevlzmom na luge Rossli, p. St. See map in appendix.

arid orf.il ievo

beXXIqe dr^oXsvi-

lo eroe *!£»*•* «

.Jaalltt

.

oj ^Il9xd0 bsns±a9b 9'.:; w £ 1i

b916 ISIJJJIJ oli; s

. '

. nl niesS eJ-enoCI ©ff;t

.

•

aorrsdo

Y(}

8esXni,

,e9asXXXv .

I

•

^

.*£

.

*

idoG

,1

outside world.1 There followed in the wake of slow economic development in the Don an influx of immigration from the north.

Emancipa

tion of the serfs in 1861 served to augment this movement, and soon large numbers of former serfs, apparently those not tied to the village commune, arrived in the Don to join other peasants already there in a search for land or employment.

While the

Don had known non-Cossack Inhabitants for several centuries, this segment of the population threatened to engulf the Cossacks at the end of the nineteenth century.

Indeed, census informa

tion collected at the beginning of World War I placed the popu lation of the Don Oblast at 3*786,000, of which approximately 1,700,000 were Cossacks.

The rest were a mixture of native

peasants, newly-arrived peasants, townspeople, miners, and factory workers.

Despite the heavy migration, the Don possessed

a population density of 26 people per square verst, as against 2 an average of 29 people per square verst in European Russia. In the face of the changes taking place around them, the Don Cossacks were able to retain much of their old way of life which revolved around obligatory military service to the Tsar.

According to the "Cossack Regulations

last revised in

1374, the Don Cossacks with few exceptions, were liable to universal military service.

1

Although these regulations were

Dobrynin, Bor'ba s Bol'shevlzmom na luge Rossi!, p. 24.

pp.

».

; ''

•>

...

•

ww, s n o a , ! , „ .

9aori;f

n.

24 somewhat heavier than the burden imposed on the rest of the population, they took into account the customs and historic traditions of the Cossacks.

These regulations changed little

during the next forty years, and they were the basis of Don Cossack service in World War I.1 Unless he was physically unfit or had special pro fessional qualifications, every Cossack reported for military duty at the age of twenty with his own horse, equipment, and weapons (with the exception of firearms).

After spending the

first year of his eighteen years of military service in a training unit, the young Cossack entered a combat-ready firstline regiment for four years of service away from his home in the Don.

The next four years were served in a second-line

regiment stationed in the Don Territory, usually close to the Cossack's home.

He spent a third four-year block of service at

home in a third-line regiment in which he did not have to pro vide his own horse.

For his final five years of service the

Cossack entered an inactive reserve unit with the assurance that he would be called to active duty only in case of emergency The basic Cossack military formation was the cavalry regiment which was usually composed of six sotnias or squadrons. Each regiment contained about 900 men and sometimes an attached unit of horse artillery.

Haven:

Fundamental weapons were the rifle

N N Golovin, The Russian Army in the World War (New Yale'university Press, 1931)/PP. 2> 10•

2. "Kazachestvo," Bol'shaia Sovetskala Entslklopedlia, 1st ed., XXX, 621-622.

noG lo slascf srfcf 9*i9w -,sri$ ' .I «xbW| ~oiq iBlceqst 5 erf ic

Yustfllirn •xol ostfi

seaoO

Jsiif -Jiismi .

Don Oblast where a cross-section of peasants might reveal a number of combinations of real estate ownership, land tenure, and land lease.

In addition, any number of peasants might

reflect varying degrees of wealth, from the well-to-do farmer who perhaps would own outright as many as

3o

deslatlnas of land,

to the poverty-stricken peasant who had no land and either leased property or worked as a hired hand for someone else. 1

To

complicate the situation further, some peasants were the descendants of serfs who had lived in the Don before emanclpation and who, consequently, possessed more right to property than the peasants who came after emancipation.

Those peasants

who possessed no land and did not choose to work for another farmer were often forced to rent land at prices higher than the average peasant could afford.

2

Perhaps the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government t Prince L'vov, best summed up the land problem in the Don when he directed an appeal for moderation to the Ob last on April Id, 1917: The land question is particularly complicated and confused. At'first the peasantry, resettled a century and a half ago, was wedged Into the basic c ° s ®*° k latlon: later followed an influx of t e n a n ^ - a S£ l o u 1 ^^ occupying military lands and lands belonging to nomadic tribes. In addition, a considerable part of the^land in the Don Ob last belonging to office ^ of passed into the hands of -Cossacks witHTbe formed ownership. These land interrelationships were for

t

non

1.

V. Dobrynin, Bor'ba s tool'shevizmom

na luge Rossil,

pp. 17-18. 2.

Oganovskii, p. 387' of insert between pp. 384 and 385.

3.

Pomeshchlk means landlord or landowner.

51

Prince L'vov then went on t o o f f e r a d v i c e t o t h e

ptaaants on future courses of a c t i o n : Until the Constituent Assembly i s convoked, one must pursue one's own a f f a i r s , work calmly, and d i l i gently f u l f i l l one's c i v i c d u t i e s and o n e ' s d u t y t o the state, bearing firmly i n mind t h a t only by t h i s means will i t be possible t o p r e s e r v e t h e freedom won by the revolution and t o d e f e a t t h e e x t e r n a l enemy. 2 Thus, the statements of t h e P r o v i s i o n a l Government and the previous resolutions of t h e Don Cossack Congress largely ignored the immediacy of t h e land q u e s t i o n i n t h e •>):. Ob last.

Thirst f o r land p l u s t h e knowledge t h a t t h e

authorities posed no immediate s o l u t i o n f o r l a n d i n e q u a l i t i e s •oon led to a number of a g r a r i a n d i s o r d e r s .

These d i s t u r b -

we.8 usually centered around the arbitrary activities of *nt Soviets and executive committees, organizations that 'Prang up in rural , areas almost immediately after the fcbruary Revolution.3 , Soon, Don landowners began to bombard

had

th * sut horltles

l-

2-

both in

Novocherkassk and in Petrograd with

Quoted m Browder and and Kerensky, I I , 595-596.

Ibid.

A 1 Zolotov, " Period 0 0 }* 1 V e mo ^Uutsu 0 x 1" > iift n OkttaKv,! Oktiabr'

roS

lslfy

52 of complaint, describing l o c a l m a n i f e s t a t i o n s of P««»*nt discontent. At f i r s t the actions of t h e v arious peasant o r g a n l atlons seemed t o be directed a t both noble and non-noble landowners who leased land a t e s p e c i a l l y h i g h r a t e s t o l a n d less peasants.

A telegram of April 1 from s e v e r a l landowners

In thu Ust 1 -Medvedlt s k l i Okrug t o l d of t h e r e s o l u t i o n s of

ioctl land committees t o introduce compulsory low land r e n t . Ir. the event that owners did not accept t h e new r a t e s , t h e peeetntfl threatened t o s e i z e the land without compensation t o Only In a few Instances did telegrams complain

the owners.

: arbitrary land seizures, and when t h e s e s e i z u r e s d i d o c c u r , they were concentrated mainly I n t h e R o s t o v s k i i , Taganrogskii ,

*nd Donetakil Okrugs, the regions having t h e r i c h e s t land b u t ths least number of Cossack i n h a b i t a n t s . !

Thus, a c t i v i t i e s

* the Don peasants i n t h e time immediately f o l l o w i n g t h e fcbruary Revolution displayed s e v e r a l c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s :

first.

«>• initial objective was lower land r e n t s , a l t h o u g h a number Arbitrary seizures were recorded; second, p r i v a t e l a n d ^l:;-

lya

'

tha"

~ «- -in victims Of peasant

3i also'" T ~~s— L Hodu (Loscow-Leningrad•

p n e -i

53 From

the beginning, legally constituted authorities

"ttle

SUCoe3S

ln combating aSrarlan

disorders.

police were e i t h e r s y m p a t h e t i c t o t h e p e a s a n t s o r s i m p l y

• -,4^,44. Qkt1abr"TsTca3Ta^evoTTOTsIa na Donu,

etf nr «xc'

60 of this meeting, they hastened to join it, and arrived in time to learn that many of them were under house arrest.

Major

General Chernoiarov was elected the new commander of the garrison. 1 On a lower level, the enlisted men of the regiments elected company and regimental committees in compliance with Order Number One, an order that introduced the Committee System into the Russian Army.

It was the purpose of this

system to prevent counter-revolutionary actions on the part of officers; in reality, the committees contributed to disciplinary difficulties and helped lead to the breakdown of the Army. Delegates from unit committees formed a Rostov Soviet of Soldiers' Deputies on March 5.

Corporal Mel ! sitov of the 255th

Regiment was elected Chairman of the Soviet, while a highranking officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Skudre, was elected as his assistant. 2

This presented a strange picture:

Skudre, the

Deputy Commander of the 39th Infantry Brigade, was at the same time Mel 1 sitov's superior and his assistant. Representatives of the Workers 1 Soviet met with delegates from the Soldiers' Soviet to foim a united Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies late In the evening of March 5. The more moderate members of both bodies decided that It would be wise to maintain contact with the Civic Committee rather than exist alone.

1.

Consequently, the united Soviet of Workers' and

Chernoiarov, Donskala LetoglsJ., II, 41-44. -n rr rr in nktiabr'skaia revoliutslla ir T 2. Ibid. See also, V. I. verz in na Donu, p. 144.

6l Soldiers' Deputies proposed to form the Rostov Committee, a new governmental organization whose membership would be derived one-third each from the Civic Committee, the Soviet of Workers' Deputies, and the Soviet of Soldiers' Deputies. After a furious debate that lasted for several days, the members

of the Civic Committee assented to the proposal.1 From the time of its first meeting on March 10, the Rostov Committee was unable to function as an effective governing body.

The coalition between the workers and soldiers on the

one hand and the more conservative leaders of Rostov on the other hand was extremely fragile.

Banks did not want to grant

the new city government credit, and the demands of the workers for increased pay, improved living conditions, and an eighthour work-day shocked the moderates.

Then too, the united

Soviet of Workers ' and Soldiers• Deputies never really sub ordinated itself to the Rostov Committee.2

In this atmosphere

long-standing antagonisms rose to the surface, with political and ideological differences playing an important role in both the Soviet and in the Rostov Committee. Political and ideological differences tended to split the Soviet into three factions: lutlonary, and Bolshevik.

Menshevik, Socialist Revo-

As in many Soviets throughout Russia,

the Hensheviks held a dominant position in the Rostov organiza tion during the hectic days following the February Revolution.

1. 2'

r

Chernoiarov, Donskala_ LetopisS IX, ^1la»f

Sovetov na Donu, p. 67. feg also, V. ^WlHr^lill revogutsOTE SSS*. P" '

The Mensheviks, advocating a broad proletarian party and collaboration with the liberals for a democratic constitution, represented the non-Leninist faction of the Russian Social Democratic labor Party.

Although Marxists, most Mensheviks

Delievea that Russia was not developed enough to undergo a proletarian revolution; therefore, they encouraged limited participation in government while maintaining a defencist position in the war to protect the bourgeois revolution.^"

In direct contrast with the Mensheviks, the Bolsheviks believed that a small, tightly knit body of highly disciplined revolutionaries was necessary to accomplish the proletarian revolution.

Under Lenin the Bolsheviks pursued a defeatist

policy in World War I, hoping that Russian defeat would mean Marxian revolution.

However, the February Revolution caught

the Bolsheviks unaware, and the Party existed in a kind of an Ideological limbo, not knowing what course to take until Lenin's return to Russia in April, 1917.

Meanwhile, the Rostov

Bolsheviks formed a Rostov-Nakhichevan Committee, elected 19 members to the 100-man Soviet of Workers' Deputies, and Joined with the Mensheviks to pursue a minimum program until Lenin published his April Theses.

It appeared that the Bolsheviks

wielded their strongest Influence among the factory r>\-\ had sorung up in much the ^ame organizations of workers which P manner .. the —=o.1«..e fter We ««—

L e o n S

h

a

p

i

r

a

p

"

.HoJtititfW •

63 Unable to direct the activities of the Workers' Soviet with only 19 members, the Bolsheviks began to recruit members on a campaign so effective that the Rostov organization could count nearly 1,000 adherents in June, 1917. Bolshevik activities also included the publication of a newspaper, Nashe Znamia, after April, 1917.1 The Socialist Revolutionary organization was surprisingly large when compared with Lenin's Party.

At 8,000 members the

Rostov SR organization dwarfed even the Mensheviks who possessed about 5,000.

The SR paper, Zemlia :L Volia enjoyed a wide

circulation in the city, but much of the SR work was confined to the peasants in the countryside.2

The large SR organization

in Rostov was probably best explained by several factors: first, in view of the relatively recent industrialization of the area, many of the inhabitants of Rostov were probably either former peasants or the sons of peasants coming from areas where the SR18 found great sympathy; second, for the average citizen the moderate parties were probably too conservative or academic, while the Bolsheviks were too unpatriotic in their stand on the war.^ The Party of Constitutional Democrats, better known as the Kadet Party, was the last organized political

rTT^Tn HffilJsSll. Bcr 'ba za vlaat' Sovetov na Donu, p. 67Bor 'ba za vlaat' Sovetov na Donu, P- 67.

Poes of Bolshevism, pp.

at SSM-

»8'

: 31

64 commanding a n y d e g r e e o f s u p p o r t i n Rostov.

Formed by l e f t -

wing l i b e r a l s i n 1 9 0 5 , t h e Kadet P a r t y b e f o r e t h e Revolution had f a v o r e d a c o n s t i t u t i o n a l government t h a t would a t t r a c t t h e support of a l l R u s s i a . 1

After the February Revolution, the

Kadets proved u n a b l e t o compete w i t h t h e more r a d i c a l p l a t f o r m s of t h e s o c i a l i s t p a r t i e s and g e n e r a l l y l o s t f a v o r among t h e masses.

I n R o s t o v a number of c i t y l e a d e r s and members of t h e

Civic Committee, i n c l u d i n g B . F . Z e e l e r , were Kadets. The v a r i o u s p o l i t i c a l f a c t i o n s and d i v e r s e i n t e r e s t groups i n Rostov made i t e x t r e m e l y d i f f i c u l t f o r e i t h e r t h e S o v i e t o r t h e R o s t o v Committee t o accomplish much beyond a few basic reforms.

The B o l s h e v i k s , l a c k i n g a c l e a r program u n t i l

L e n i n ' s a r r i v a l i n R u s s i a , a t f i r s t u n i t e d w i t h t h e Mensheviks t o campaign f o r a minimum program aimed a t improving t h e working conditions of the proletariat.^

One t a n g i b l e r e s u l t of t h i s

s h o r t - l i v e d c o a l i t i o n was t h e i n t r o d u c t i o n i n Rostov and Nakhichevan of t h e e i g h t - h o u r work-day.

However, t h e o r d e r

Introducing the new work-day was published by the Soviet without prior consultation with the Rostov Committee.3

In much the same

manner as the soldiers' committees had contributed to the breakdown of power within the Army, the Rostov Soviet was con tributing to the breakdown of legal authority in Rostov. Both the city government of Rostov and the Oblast

1. Leonard Schapiro, Union (New York: Vintage ESSks, 19^), v. I . = . « »a

3.

Bor ' b a a

s

Sovjt™ J !

^ » PP'

53~5"'

•

government In Novocherkassk displayed growing concern over the conduct of the reserve infantry regiments in the Rostov garri son.

As Ataman a n d Commander o f a l l ar m ed f o r c e s i n t h e Don,

L i e u t e n a n t - C o l o n e 1 V o l o s h i n o v w a s e s p e c i a l l y a l a r m e d when h e h e a r d t h a t d i s c i p l i n e h a d p r a c t i c a l l y c e a s e d t o e x i s t among t h e reserve regiments.

A f t e r t h e y r e f u s e d t o t a k e a n o a t h of

loyalty to the Provisional Government, Voloshinov travelled to Rostov for a first-hand look a t the regiments.

An a l l - d a y

I n s p e c t i o n on A p r i l 1 7 r e v e a l e d t o V o l o s h i n o v n o t o n l y a l a c k of d i s c i p l i n e b u t a l s o a n e x t r e m e l y n e g a t i v e a t t i t u d e among the soldiers towards the war.

A f t e r d i n n e r o n t h e same d a y ,

t h e S o v i e t o f W o r k e r s ' D e p u t i e s m e t w i t h Ataman V o l o s h i n o v a n d accused him of s t i r r i n g the soldiers against the workers.

In

r e p l y t h e Ataman t o l d t h e d e p u t i e s t h a t h e "was n o t a b l e t o permit workers' interference in the instruction of soldiers serving in the regiments.

To e x t r i c a t e h i m s e l f from a

potentially d i f f i c u l t situation, Voloshinov asserted that he was a n o l d r e v o l u t i o n a r y a n d t h e n l e f t b e f o r e t h e d e p u t i e s could ask any more questions.

To a c e r t a i n e x t e n t , t h i s e n

c o u n t e r b e t w e e n t h e Ataman a n d t h e S o v i e t d i s p l a y e d t h e l a t e n t hostility that existed between the workers and the representa

tlves of the Cossacks. Much o f t h e d e m o r a l i z a t i o n w i t h i n t h e r e s e r v e r e g i m e n t s was t h e r e s u l t o f B o l s h e v i k p r o p a g a n d a .

The i m m e d i a t e c o n s e

q u e n c e o f L e n i n 1 s a r r i v a l i n R u s s i a w as t h a t t h e R o s t o v

1.

C h e m o l a r o v , Donskala L e t o g i s J . , I I , ^ 6 - 4 8 .

Bolsheviks ended their embarked on an Independent withdrawal of

or which

plrt

fro. the

the April Theses ln whioh Lenin said,

66

„

atn

tho

^

ln

. , „„t the slightest

concession must be made to 'revolutionary defenclsm'.1,1

Among

the ranks of the reserve Infantrymen this position gained immediate popularity.

Soon the Bolsheviks virtually con

trolled the 249th Regiment and exerted strong influence among the other reserve units.^ On June 1:5, armed detachments of the Rostov garrison appeared in the streets to support a Bolshevik anti-government demonstration. the War.'

and

Soldiers carried placards reading "Down with All Power to the Soviets.'"

Workers from several

factories Joined the soldiers, and it was only with some difficulty that the Rostov police were able to disperse the demonstrators.^

Alarmed by the growing influence of the

Bolsheviks, Menshevik and SR members of the Soviet moved to censure the Party of Lenin, but met strong opposition from large numbers of workers and soldiers.

When the excitement of

the demonstrations died away, the various parties began to cam paign strenuously for city elections coming in July, 1917Preparation for the city elections in Rostov doubled as an opportunity for some of the political parties to begin an Oblastwide campaign for elections to the forthcoming Constituent Assembly. !.

Quoted in Browder and Kerensky, IX, 1207.

2.

Bor'ba za vlastj Sovgtgv na Donu, PP- 75-76.

3.

Ibid., p. 70.

vsrfsnei

£

67 or of

p a r t i c u l a r Importance i n t h i s campaign were s e v e r a l

the Don Oblast t h a t had remained r e l a t i v e l y u n t o u c h e d

„ the February Revolution. • h a r e

#ptat

One of t h e s e was t h e D o n e t s B a s i n

numbers of miners r e s i d e d i n s c a t t e r e d m i n i n g

settlements, the l a r g e s t of which was Kamenskala.

Because of

tne dispersion of mining o p e r a t i o n s and b e c a u s e o f t h e p r e s e n c e of s substantial Cossack p o p u l a t i o n , a u n i f i e d and o r g a n i z e d •orktr movement did n o t Immediately a p p e a r i n Kamenskala following the February R e v o l u t i o n .

I n t h e b e g i n n i n g o f March,

a Kamenskala Civic Committee took c o n t r o l of t h e s u r r o u n d i n g region.

A Cossack, A. P. B o g a e v s k i i , l e d t h e Committee whic h

cooperated c l o s e l y with t h e O b l a s t government i n N o v o c h e r k a s s k . Unlike Rostov, n e i t h e r t h e Mensheviks n o r t h e B o l s h e v i k s w e r e •bit to make any s u b s t a n t i a l I n r o a d s i n t o t h e a c t i v i t i e s o f the Civic Committee.

The r e s u l t was t h a t t h e Mensheviks,

Bolsheviks, and S o c i a l i s t R e v o l u t i o n a r i e s were c o n f i n e d t o juarrellng among themselves i n t h e Kamenskala S o v i e t o f Yorkers 1 Deputies.

I t was n o t u n t i l June t h a t any o f t h e s e

P*rtles had r e c r u i t e d enough a g i t a t o r s t o b e g i n p r o f i t a b l e Political a c t i v i t y among t h e c o a l m i n e r s o f t h e a r e a . 1 i n c o n t r a s t with t h e p a r t i s a n a c t i v i t y o f p o l i t i c a l ""

c°"*c'"

i„

P„p,„tlon,

Voennoe

jsrtt a-.sIdO OCH

10

yofioas*!

aifxSmm urn*

sricr io

Jon cit> Jaaaevoai s< .

ertt lo

*a*

•

.ay-is —o.ijiio, ..0

a

ono.ua

tJIvlfmrUo*

Iw camsaoc ai ai. 3^

soaaaov '

: wooaoMj

68 f o r t h e e l e c t i o n s t o t h e C o n s t i t u e n t Assembly.

Of more im

mediate importance t o t h e Cossacks was the e l e c t i o n of a permanent Ataman.

When t h e F i r s t Krug met i n Novocherkassk,

t he Cossack d e l e g a t e s completed t h e i r a c t i v i t i e s on June 18 by e l e c t i n g Aleksel Makslmovlch Kaledin a s t h e new leader of t he Don Voisko.

Kaledin, a former General of cavalry, a t f i r s t

promised t o provide t h e s t r o n g l e a d e r s h i p needed so desperately t o weld t h e Don Oblast i n t o a more homogeneous p o l i t i c a l u n i t . In t h e absence of any organized r e p r e s e n t a t i v e non-Cossack bodies, Kaledin and h i s Voisko Government became the r u l i n g power for both Cossack and non-Cossack inhabitants of the Don Territory. 1 "

But a s new c r i s e s began t o t h r e a t e n the existence

of t h e P r o v i s i o n a l Government I n Petrograd, Kaledin and other Don l e a d e r s were unable t o devote f u l l a t t e n t i o n t o matters i n t h e i r own O b l a s t . The result was that the centrifugal tendencies that tended t o s e p a r a t e t h e various i n h a b i t a n t s of t h e Don met no concerted a c t i o n from t h e Cossacks o r any o t h e r organized group. Even had Kaledin possessed t h e necessary time t o take e f f e c t i v e a c t i o n , t h e m i l i t a r y b a s i s of h i s power, the Don Cossack r e g i ments, was a t t h e f r o n t .

Without t h e m i l i t a r y force of t h e

Cossack regiments t o back h i s d e c i s i o n s , Kaledin.s power proved effective only In

Cossack

-dominated areas.

Not over two months a f t e r Kaledin took power, the

1.

For an eyewitness a c c o s t of t h e ^ i r g ^ . ( «ee General

69 question of elections to the Constituent Assembly rose to con front the Cossacks.

When they chose to appear on the list of

the Constitutional Democrats, nearly every important group in the Don had Identified itself with a major political party of national significance.

The actual elections did nothing but

confirm those social cleavages that were present in most areas of the Don Irom the first days of the February Revolution.

The

Kadet list on which the Cossacks appeared drew 640,000 votes or 45 percent of the total.

The Socialist Revolutionaries

polled 4b0,000 votes, or a little more than 30 percent of the total.

The other major recipient of votes was the Bolshevik

Party with 205,000 votes.

The percentage of the total votes

received by each list represented the percentage of the Don population composed by three groups: workers.1

Cossacks, peasants, and

Thus, there was little change in the attitudes of

the three basic components of the population of the Don Ob last from February, 1917 to the time of the elections to the Constituent Assembly.2

The only major alteration was the

political realignment of the majority of the workers who changed from the Mensheviks to the Bolsheviks, but this tendency had already begun as early as June.

The following year would

find the only groups in the Don that possessed a solid platform and strong internal unity locked in civil war:

the Don Cossacks

and the Bolsheviks. 1.

2 251.

,

T

Antonov-Oveeenko, I ,

loll See also, Oliver H. Radkey, ^ Iituent Assembly of 19j-7

Oliver H. Radkey, The Agrarian

ffnps of Bolshevism, p.

. __

• ivl

Chapter IV CONCLUSIONS

According to a legend that dated from the fifteenth century, a newcomer t o the steppes of south Russia could besome a C o s s a c k s i m p l y b y m a k i n g t h e s i g n of t h e c r o s s and b y asserting his belief in Christ and the Holy Trinity.

Whether

or not t h i s legend was true had l i t t l e subsequent effect, for in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Cossacks virtually closed their ranks to outsiders.

When

i m m i g r a n t s a n d t h e i r d e s c e n d a n t s c o u l d n o l o n g e r become C o s s a c k s e i t h e r b y p a s s i n g some s o r t o f a t e s t o r b y r e s i d i n g i n t h e Don, a d i s t i n c t s o c i a l g r o u p o f n o n - C o s s a c k s a p p e a r e d i n t h e Don s t e p p e s . A t f i r s t t h i s g r o u p w as composed c h i e f l y of s e r f s who eventually became free peasants with landholdlng rights after 1861.

I n t h e l a s t h a l f o f t h e n i n e t e e n t h c e n t u r y , economic

development and renewed migration not only Increased the number o f p e a s a n t s b u t a l s o c r e a t e d a n o t h e r s i z e a b l e n o n Cossack group residing in urban areas.

Despite the latter

d e v e l o p m e n t , t h e C o s s a c k s a n d t h e p e a s a n t s t o g e t h e r forme m a j o r i t y o f t h e p o p u l a t i o n o f t h e Don O b l a s t . (70)

A lthough

e

oii..

.1

two groups shared l i t t l e i n t h e f o r , of t r a d i t i o n , both held " one common I n t e r e s t :

they owed t h e i r livelihood t o the

a v a i l a b i l i t y of farm l a n d .

For various reasons the Cossacks

as a group possessed t h e m a j o r i t y of land i n t h e Don on the eve of t h e February Revolution.

A f t e r February, 1917, the

continued Cossack p o s s e s s i o n of t h e land was a chief source of irritation for the peasants.

This i r r i t a t i o n l e d t o a growing

i n s t a b i l i t y i n r u r a l a r e a s where peasant demands and seizures threatened anarchy. Non-Cossack urban a r e a s c o n s t i t u t e d another source of i n s t a b i l i t y i n t h e Den. Ob l a s t a f t e r t h e February Revolution. Both i n Novocherkassk and i n Rostov l a r g e numbers of workers displayed a growing i n c l i n a t i o n toward radicalism, with l o c a l g a r r i s o n s of r e s e r v e infantrymen o f t e n i n t h e vanguard of t h i s movement.

The presence of a Cossack majority i n Novocherkassk

acted a s a brake on t h e a c t i v i t i e s of t h e workers and the s o l d i e r s , but t h e r e was no such check a g a i n s t an increase of radicalism i n Rostov.

The r e s u l t was t h a t t h e two chief c i t i e s

of t h e Don followed d i f f e r e n t l i n e s of p o l i t i c a l development a f t e r February.

I n Novocherkassk, Cossack and

non

-Cossack

leaders were a b l e t o form a v i a b l e l o c a l government based e s s e n t i a l l y on t h e acquiescence and p a r t i c i p a t i o n of the Cossacks. In Rostov, p o l i t i c a l power continued t o d r i f t on the t i d e of r e v o l u t i o n , always a t t h e mercy of p r e v a i l i n g antagonisms and political differences. « POIIMC.1

Subsequently, t h e s i t u a t i o n worsened «• >»•""

°

:

72 other susceptible areas in the Don. For the Don Territory as a unit, there was the danger that the continued political and social instability of some areas would paralyze efforts at building a strong regional government.

Even before this task was begun, it was apparent

that the Don suffered from both the lack of a guiding precedent and an effective coercive police power.

For Cossack leaders,

it seemed rational to believe that they should base an Oblastwide government on the Cossacks because only the Cossacks had emerged from the February Revolution as a cohesive political and social unit.

However, the Cossacks did not constitute

the necessary majority needed for a democratic rule, and their interests often ran counter to the interests of the nonCossack population.

Because of these reasons, any attempt

at constructing an Oblast government solely around the Cossacks would have been to court further political Instability. Yet, this was the choice that the Cossack leaders made when they took control of the Don Executive Committee and then formed their own Volsko government to rule the Don Territory in view of the Instability already so apparent In the n rm it is difficult to explain Don after the February Revolution,

^«.——:

i p base of operations late in lyir. the Cossacks as a base oi p

P™,.dl„e

SO rspldly

,,w,rl,nc.d 1» van.-

in a position to know the localities.

Perhaps another answer was that

choice in the matter.

r:i llttle

APPENDIX

(73)

>

i )

i

/ ( '

i