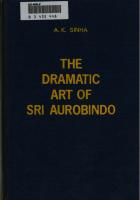

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

Originally presented as the author's thesis.

576 71 7MB

English Pages [237] Year 1979

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

UC-NRLF

,

MIIHIiniHI

B 3

MBS

44A

A. K. SINHA

THE DRAMATIC ART OF SRI AUROBINDO I

i

I

THE DRAMATIC ART OF SRI AUROBINDO

A . K. SINHA

S. CHAND

& COMPANY LTD

RAM NAGAR, NEW DELHI-110055

S. CHANO & COMPANY LTD * A M NAG AR, N EW DELHl-l 10055 Show Room ; 4/16-B, Asaf All Road, New Delhi-110002 Brarndm i Mai Hiran G»m , Jullundur-144008 Aminabad Park, Lucknow-226001 Btackia Houta, 103/5. W tlchin d Hirichand M iri, Opp. G.P.O., Bombay-400001 35. Anna Salai, Madrat-600002 •*1, Banariea Road. Ernakulam North. Cochin-482018

285/J. Bipin Bahari Gan|uli Straat, Calcutta*7000l2 Sultan Baxar, Hydarabad-500001 3. Gandhi S ifa r East* Nacpur-440002 K.P.C.C Buildinf, Raca Coursa Road* Bangaloro-560009 Khaanchi Road, Patna-800004

CAT FOR MAIN

First Published 1979

Published by S. Chand & Company Ltd, Ram Nagar, New Delhi-110055 end printed et Rajendra Ravlndra Printers (Pvt) Ltd, Rom Nagar, New DelhUiOQt*,

M /J f/vJ

Preface Although Sri Aurobindo’s philosophical, poetical and critical writings have received the attention of scholars and critics, yet his dramatic works have so far not received the attention that they deserve. One of its reasons is that his plays were published after his death. It is noteworthy that when K.R.S. Iyengar’s monumental study of Sri Aurobindo appeared in 1945 only one play, Perseus the Deliverer, was available to him. The study, therefore, devotes only a few pages to a discussion of Sri Aurobindo’s dramatic genius. K .R .S . Iyengar’s mono* graph on Sri Aurobindo, published in 1961, was intended as an introductory volume on Sri Aurobindo and as such does little justice to his dramatic genius although it does examine, very briefly indeed, all the complete plays of Sri Aurobindo. The only full length study of Sri Aurobindo’s plays is M. V. Seetaraman’s StuUies in Sri Aurobindo’s Dramatic Poems published in 1964. Although it successfully brings out the main thought in Sri Auirobindo’s plays, it does not say anything really significant on the plot-structure, style and imagery of his plays. Moreover, it seems to me, much remains to be said in Seetaraman’s book on even the themes and visions in Sri Aurobindo’s plays. It is for this reason that this study of Sri Aurobindo’s plays was undertaken by me. The plays of Sri Aurobindo are some of his earliest literary works. They were all written during the period be tween 1893 and 1918 and much before The Life Divine (19391940) and Savitri (1950) which are Sri Aurobindo’s master pieces. Three of these plays— Vasavadutta„ Eric and The Viziers of Bassora bear the subtitle ‘ a dramatic romance’ and romance is indeed the prevailing quality of each of these plays. It may, therefore, appear futile to look for any consistent philo

Iv

Preface

sophy of life in these plays which were the creations of Sri Aurobindo’s youth. A critical study of these plays, however, reveals that although essentially aesthetic creations, these writings do contain germs of Sri Aurobindo’s thought which found full expression later on in his philosophical treatise, The Life Divine and his epic poem Savitri. It is noteworthy that Sri Aurobindo’s theory of evolution discussed in The Life Divine is reflected in his plays also. As a matter of fact the thought in 'Sri Aurobindo’s plays can be fully grasped only when it is studied in relation to his philosophical ideas in general. It is for this reason that I have outlined some of these philosophical ideas of Sri Aurobindo in the first chapter o f this book. The plays have been discussed in this book in chronologi cal order. Such a scheme has been adopted in order to have an idea of the development of the dramatic art of Sri Auro bindo. It is noteworthy that the second dramatic work of Sri Aurobindo, i.e. Prince of Edur, was left in an incomplete form. I have tried to establish that the play in the third Act took, perhaps in spite of 'Sri Aurobindo, an unexpected turn, and Sri Aurobindo found it impossible to reconcile his original intention with the new development. The play was, therefore, abandoned. It, therefore, shows that Sri Auro bindo was not able to achieve complete mastery of his dramatic art. But this mastery is fully achieved in his third play, i.e. Perseus the Deliverer. The last four plays, viz. Perseus the Deliverer, Eric, Vasavadutta and Rodogune, show Siri Aurobindo at his best as a playwright. The first section of this book is a general introduction to Sri Aurobindo, the poet, patriot and philosopher. In its second section, I have undertaken a critical study of each play. Chapters III to V III present an analytical study of the plays, particularly from the point of view of characterisa tion and thought-content. Chapters IX and X discuss the dramatic technique of Sri Aurobindo, especially his plotstructure, use of verse, the element of music and imagery. Chapter X I is an attempt to determine the place of Sri

Preface

v

Aurobindo in the tradition of English verse drama. The last chapter, which sums up the results of the investigation, attempts to assess the mind and art of Sri Aurobindo as a playwright. I wrote this book as a thesis for the Ph.D. degree and I am grateful to the authorities of the University of Bihar, Muzaffarpur for granting me a publieation-subsidy to get it pub lished. I am deeply indebted to Sri S. L. Gupta, Managing Director, S. Chand & Company Ltd, New Delhi, and his staff fo r undertaking the publication of this work in the midst of their multifarious and pressing duties. I must thank the Librarian of Sri Aurobindo Inter* national Centre of Education, Pondicherry and also of the Patna University and National Library, Calcutta. I thank the authorities of several Sri Aurobindo Study Centres for the co operation and help they rendered me. My thanks are also due to the Manager, Sales Division, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondi cherry for his help. I am also grateful to Dr Sri Krishna Prasad, University Professor of English, Magadh University and late Dr R. S. Varma, University Professor o f English, University of Bihar, Muzaffarpur for the guidance which I received from them, in the early stage of my work. Last but not the least, I must express my deep sense of gratitude to my guide D r K. R. Chatterjee, Reader in English, University of Bihar, Muzaffarpur. It was mostly due to his encouragement and constant guidance that this work could be completed. A. K. Sinha

/

Contents Preface

«•»

in

SECTION O N E : INTRODUCTION I. II.

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius Sri Aurobindo’s Plays : A Note o f Their Chronological Order

3— 20 21— 26

SECTION TW O : INTERPRETATION m.

The Viziero o f Bassora

29— 61

IV.

Prinoe of Edur

52— 67

Perseus the Deliverer

68—90

V.

91— 104

VI.

Erie

VJLl.

Vasavadutta

105— 119

Rodogune

120—144

Structure and Style in Sri Aurobindo

145— 164

Imagery in Sri Aurobindo’s Plays

165— 184

VIII. IX. X.

SECTION THREE : CONCLUSION X I. X II.

Sri Aurobindo and the Modern Revivers of Poetie Drama

187— 197

The Mind and Art o f Sri Aurobindo as a Playwright : A Summing up

198—209

Appendix o f Longer Notes

210—220

Select Bibliography

221—227

1

SECTION ONE

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

SRI AUROBINDO : A LIFE-SKETCH Sri Aurobindo, a unique product of modern Indian Renais sance, was bom on August 15, 1872. He was the third son o f Dr. Krishna Dhan Ghosh who belonged to a wealthy and accomplished family of Calcutta. After receiving his medical education at the University of Calcutta, Dr. Ghosh sailed to England where he studied for the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Aberdeen. Having obtained the degree, he returned to India as a fully anglicised gentle man. He soon entered the Indian Medical Service and served as a Civil Surgeon in various parts of the country. Dr. Krishna Dhan Ghosh, who was steeped in western thought, decided to give his children the English type of education. As such Sri Aurobindo was sent to the Lorreto Convent iSichool at Darjeeling at the age of five only. At the age of seven he, along with his two brothers, was taken to England and put under the guardianship of Dr. Drewetts at Manchester. The Drewetts took care to see to it that the children did not imbibe Indian ways of life and manners. After receiving a few years of private coaching at the Drewetts, Sri Aurobindo joined St. Paul’s School in London in 1885. Here he won the Buttleworth prize for Literature and the Bedford prize for History. He passed out of St. 3

4

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

Paul’s School with senior classical scholarship. He was next admitted to the King’s College at Cambridge where he remained for two years. There he won several prizes for Greek and Latin poetry. He secured first class in the first part of Tripos but did not try to secure the degree as he had no intention to take up an academical career. In 1890 he sat in the open competitive examination for the Indian Civil Service and secured record marks in Greek and Latin and passed the written examination creditably. He, however, failed in the riding test. He was given another chance to pass the test. But he deliberately avoided presenting himself in time for the test as he by that time ceased to have interest in the I.C.S. He now hated to become a collaborator and cham pion of the British Rule in India. The British Government too had become suspicious of him because of his association with Indian Majlis at Cambridge and his open criticism of the British rule in India. His entire student life was brilliant in character and he gave ample proof of possessing an intellect of an extraordinary nature. The sharpness of his intellect, his quick grasping power and his industry attracted Gaekwar of Baroda, who, at that time, was in England. Sri Aurobindo was introduced to him by S£r Henry Cotton’s brother. The Gaekwar was so much impressed by Sri Aurobindo that he at once took him in the service of his own State. Sri Aurobindo, along with the Gaekwar, sailed back to India in February 1893. He remained in the service o f Baroda State from .1893 to 1906 ’ serving the State in various capacities, chiefly as Professor of English and French at the Baroda Government College and also as the Vice-Principal of the College. The decision of the British Government to partition Bengal in 1905 infuriated Sri Aurobindo and he decided to join the political movement for the liberation of India from the British rule. In 1906 he left the service of the State for good and joined the staff of the newly founded Bengal National College as its Principal. Also during this very period he joined the Indian National /

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

5

Congress. The Indian National Congress at that time was divided internally into two blocs, viz. the Nationalists (also called the Extremists) and the Moderates. Tilak was the leader of the Nationalists and Sri Aurobindo, at once, associated himself with him and his group. The Nationalists put ‘ Swaraj’ as their goal as against the Moderates’ plan of establishing a colonial self-government through a slow and gradual process. Sri Aurobindo devoted himself whole heartedly towards making his group powerful enough to dominate the Congress and turn it into an effective organiza tion. During this very period (i.e. between 1906 and 1907) Sri Aurobindo became the acting editor of The Bandemataram which had become an organ of the Nationalists party, and it was during this period of his editorship that the daily became a symbol of national aspirations. With Sri Aurobindo being arrested and sent to jail in 1908 the paper became defunct. He was kept, as an undertrial prisoner, in Alipore jail for a whole year. After his acquittal in 1909 he found the party and nation in shambles. He, almost singlehandedly, took up the job of reviving them back to life. The Karmayogin, an English weekly, and The Dharma, a Bengali weekly, were started by him during this period in order to keep the flame of nationalism burning and also to teach his country men how to mould themselves into a living, dynamic and everprogressive people. But he soon realised that the nation was not yet mature enough to receive what he would have very much liked to give and that he was much ahead of his time. At the same time he now came under an intense pressure from his innerself to tap the spiritual powers of yoga for not only the political emancipation of his country but the higher and nobler release of mankind from the fetters of ignorance, disease, incapacity and death. In February 1910 he actually got a ‘ directive ( adesh) from above and it was in pursuance of this that he retired from active politics in favour of the higher life of the spirit. In fact he had begun receiving divine messages in this direction as early as 1905, the year o f the

6

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

famous Alipore Case, as will be dear from his KoranKahini and Uttarpara speech.1 ‘ On that occasion, however, he had proved weak and had refused to listen to that voice; politics and poetry were too dear to him then and he could not give them u p’.* But during the period between 1910 and 1914 he devoted himself almost exclusively to undergoing spiritual exercises (Sadhana), acquiring perfection of the innerself, and putting into practice what his constant and ceaseless meditation upon the Oita seemed to tell him : Slay then desire, put away attachment to the outwardness of things. Separate yourself from all that comes to you as outward touches and solicitations, as objects of the mind and senses. Learn to bear and reject all the rush of passions and to remain securely seated in yourself even while they rage in your members, until at last they cease to affect any part of your nature. Bear and put away similarly the forceful attacks and even the slightest in sinuating touches of joys and sorrow. Cast away liking and disliking, destroy preference and hatred, root out shrinking and repugnance. Let there be a calm indiffer ence to those things and all the objects of desire ii\ all your nature. Look on them with the silent and tranquil regard of an impersonal spirit.* During this period of four years (i.e. from 1910 to 1914) o f ‘ silent yoga’ he achieved new vision and a new power of action. In 1914 he began the publication of The Arya, a philosophical monthly. It was in this monthly that all his major works such as the Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Essays on the Oita, The Human Cycle» The Ideal o f Human Unity, The Secret of Veda, Foundation of Indian Culture, The Future Poetry, etc., first appeared in series. The Arya continued to be published regularly till 1921, i.e. for full six years, when its publication ceased. While thus actively engaged in giving knowledge and wisdom to the world on a massive and comprehensive scale, Sri Aurobindo continued to set himself to the hardest task of bringing upon the earth the dynamic descent of the supermind, and to— Open the gate where Thy children wait In Thy world of beauty undarkened/

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

7

He completed the first phase of this stupendous task on 24 November, 1926, when he realised what he called the overmind in his physical being itself. This day is known as the Day of Realisation (Siddhi Day), for it was on this day that he came to realise in himself divine consciousness. He himself became what he conceived of the Arhat, the completed Aryan, that is to say, he realised in himself the essence of what he himself wrote in the following lines : Although consenting here to a mortal body H e is the undying, limit and bond he knows not; F or him the aeons are a playground, Life and its deeds are his splendid shadow* In devoting himself exclusively to the life of the spirit he had desired to bring one day a complete transformation of the face of the world* But it was not the end of the story. His ultimate aim was to bring down the power of the supermind in the physical self and this was achieved in a strange way. The wheel of his spiritual progress completed its circle on 5 December, 1950, when Sri Aurobindo is said to have died. His followers believe that on this day Sri Aurobindo brought down the supramental light (symbolizing the supermind) in his own body. The divine order or adesh : To embrace, to melt and mix Two beings into one................. ’ ' was thus fulfilled. This was, therefore, not death but the widening of a soul into ‘ measureless sight’. As Sri Aurobindo himself wrote in one of his last poems : My soul unhorizoned widens to measureless sight, My body is God’s happy living tool. My spirit a vast sun of deathless light. His death was a crowning spiritual victory for the supermind. The supermind, as the Mother (Madame M. Alfassa of Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, was Sri Aurobindo’s collabo rator from 1914 to 1950) has been telling us again and again,

8

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

has already begun to get established and to do its subtle secret work of transformation here and now. It was the completion o f the physical life cycle of a great man : Luminous he moved away; behind him Death Went slowly with his noiseless tread, as seen In dream built fields shadowy herdsman glides Behind some wanderer from his voiceless herds.* SRI AUROBINDO AS A NATIONALIST Sri Aurobindo was a great nationalist. The resolve to devote himself to the service of his nation and its freedom was taken by him during his stay in England. It was in pursuance of this decision that immediately after his return to India he set himself to the task of familiarising himself with the political atmosphere of contemporary India. It did not take Sri Aurobindo much time in finding out the facts and reaching the genesis of the troubles and problems, faced by the Indian freedom movement. He, at once, framed his method of approach to the same and started publishing political writings in order to awaken the nation to the realisation of the utter necessity of freedom and to acquaint it with his own way of achieving it. As a nationalist he started with a three-pronged action : First, there was the action with which he started, a secret revolutionary propaganda and organization of which the central object was the preparation of an armed insurrec tion. Secondly, there was a public propaganda intended to correct the whole nation to the ideal of independence which was regarded, when he entered into politics, by the vast majority of Indians as unpractical and impossible, an almost insane chimera............. Thirdly, there was the organisation of the people to carry on a public and united opposition and undermining of the foreign rule through an increasing non-co-operation and passive resistance.1" During those days there was no political party that could openly claim full independence for India and this led Sri Aurobindo to associate himself with the revolutionaries working secretly. Later on he joined the Nationalists’ group of the Indian Congress and his ties with revolutionaries were virtual-

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

9

ly snapped. Nevertheless ‘ at no tim e,...........did he reject the use of force as and when necessary in order to bring about the emancipation of the motherland’.11 As a nationalist and a soldier of the Indian freedom struggle he proved to be an indefatigable worker and an utterly selfless and inspiring leader—a leader who at once commanded love and respect of all those who came in contact with him directly or indirectly. He never asked anything for himself. His people and his nation were of prime significance for him and he gave little consideration to his own self, as will be clear from his own speech quoted partly below : I f thou art, then thou knowest my heart........... I do not ask anything that others ask for. I ask only for strength to uplift this nation. I ask only to be allowed to live and work for this people whom I love and to whom I pray that I may devote my life.” He was confident that the claim of India to live as an inde pendent nation was a just and proper claim and that India was sure to win her freedom. In one of his speeches he illustrated his view thus : Our object, our claim is that we shall not perish as a nation. Any authority that goes against this object will dash itself against the eternal throne of justice—it will dash itself against the laws of God, and be broken to pieces” And History has noted that his view was correct and it was translated into reality. His self-sacrifice and single-minded devotion to the country’s cause were amply appreciated by his countrymen. This appreciation was well demonstrated by the response that the people of India gave to the appeal made by his sister Srimati Sarojini to contribute to the Defence Fund which was raised during the t^ial of Alipore Case. Response came from all directions. In the words of Dr. Iyengar :— ............. it came from the most unexpected places. A blindbeggar— all honour to him ! gave Srimati Sarojini out of the alms he had assiduously collected, perhaps over a

10

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo period of a month or even a year; a poor student, by denying himself his daily tiffin, gave a modest contribu tion; the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha bestirred itself to make collections for the Defence Fund. And other individuals and agencies also interested themselves in making proper arrangements for the defence of Sri Aurobindo.1*

His political thoughts have a spiritual undertone as they are the experiences of a saint-politician. In his opinion nationalism was a religion. He says ‘ Nationalism is not a mere political programme, nationalism is a religion that has come from God; nationalism is a creed which you shall have to live........ Nationalism for Sri Aurobindo, thus, was not mere patriotism; it was a way of living and it had the strength of God. Similarly, nation for him was not merely a geographical presence but a divine entity. Defining a nation Sri Aurobindo writes : For what is a nation ? What is our mother country f It is not a piece of earth, nor a figure of speech, nor a fiction of the mind. It is a mighty shakti, composed of all the shakties of all the millions of units that make up the nation, just as ‘ Bhawani Mahisa Mardini’ sprang into being from the shakti of all the millions of gods assembled in one mass of force and welded into unity. The shakti we call India, ‘ Bhawani Bharati’, is the living unity of the shaktis of three hundred million people........ 18 India for him was a ‘ living and pulsating spiritual entity’,17 it was the Mother and he stood for the realization of ‘ the vision of the Mother’ and ‘ the perpetual contemplation, adoration and service of the Mother’.” He was ready to undergo any sort of trial and tribulation and for any length of time while serving the Mother. He believed that : Repression is nothing but the hammer of God that is beating us into shape so that we may be moved into a mighty nation and an instrument for His work in the world. We are iron upon His anvil and the blows are showering upon us, not to destroy, but to recreate, with out suffering there can be no growth.19 Explaining what he meant by passive resistance, lie once said: Passive resistance means two things. It means first that

Sri Aurobindo : A Virsatile Genius

11

in eertain matters we shall not co-operate with the Gov ernment of this country, until it gives us what we consider our rights. Secondly, if we are persecuted, if the plough of repression is passed over us, we shall meet it, not by violence, but by lawful means* It is noteworthy that these concepts of nation, nationalism, repression and passive resistance, were later on emphasised during the period of Indian independence struggle. SRI AUROBINDO : PHILOSOPHER AND TRANSCENDENT ALIST Sri Aurobindo was a great philosopher and seer, almost in the line of vedic and upanishadic poet-seers. His philosophy deals with ceaseless striving, from time immemorial, of man kind towards the achievement of divinity. It is ‘ not the result of his seeking, but a result of his finding and discovery’.” The Life Divine f his greatest philosophical work, is a monumental work in which he made an original contribution in the field of philosophical thought of the modern world. In nature it is at once visionary and revelatory. It is both vast in range and massive in bulk. This metaphysic.il treatise is divided into three sections : Vol. I ‘ Omnipresent Reality and the Uni verse’ ; Vol. II, Part I, The Infinite Consciousness and the Ignorance’ ; and Vol. II, Part II, ‘ The Knowledge and the Spiritual Evolution’. The book explains the different processes of Sri Aurobindo’s conception of the spiritual evolution. Dr. Karan Singh writes : According to this theory, creation began when a part of the supreme, Unconditioned and Absolute Reality plung ed into the grossest and densest matter. From the dawn of creation the spirit that was involved in matter began its slow but sure evolution on the path which leads back to its source of origin. After aeons life began to make its appearance in primitive forms which gradually evolved upwards. Then, after another tremendous gap, mind first appeared among living creatures. The next step upwards was the advent of the human race when intellect began to assume the dominating role. This, however, is by no means

12

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo the final phase of evolution. In fact it is an intermediate stage, and mankind is now poised on the threshold of the next leap forward in the evolutionary process. This step is the evolution of the mind to Supermind, the luminous realm of Truth-Consciousness. The instruments of this Supermind will be intuition and direct cognition rather than the imperfect reasoning intellect which our race possesses at present*

According to Sri Aurobindo, this process of evolution as manifested in the vegetable and animal kingdom is a blind though spontaneous process. But man with the help of the Superconscient that will descend to his help may become blissful and gradually progressive one. If he so wills and endeavour, he can directly participate in this process and hasten it to a quick and perfect culmination. In the chapter on ‘ Ascent and Integration’ Sri Aurobindo explains the nature of the process of evolution : The principle of the process of evolution is a foundation, from that foundation an ascent, in that ascent a reversal of consciousness and, from the greater height and wideness gained an action of change and new integration of the whole nature.* The different stages of the ascent are described by Sri Auro bindo in these wrods : These gradations may be summarily described as a series of sublimations of the consciousness through Higher Mind, Illumined Mind and Intuition into Overmind and beyond it; there is a succession of Self-Transmutation at the summit of which lies the Supermind or Divine Gnosis........ Each stage of this ascent is therefore a general, if Hot a total, conversion o f the being into a new light and power of greater existence.** He predieted that a change from the mental to the supramental condition was inevitable : ‘ the supramental change is a thing decreed and inevitable in the evolution of the earth-consciousnese”* and this process would continue till the desired stage of evolution and spiritual transformation is achieved. Sri

Sri Aurobindo : A Virsatile Genius

13

Aurobindo, thus, presented a vision of the future course of humanity. It is the vision of a gradual but definite and constant transformation of the life-pattem on this earth into the Divine Life, i.e. into the ‘ Satchidananda’ (Existence : Conscious Force : Bliss) stage. It is the vision of a supramental prin ciple : ‘ A supramental principle and its cosmic operation once established permanently on its own basis, the intervening powers of Overmind and Spiritual Mind could be found securely upon it and reach their own perfection; they would become in the earth existence a hierarchy of states of consciousness rising out of Mind and physical life to the supreme spiritual lever." This process of gradual transform ation from the limited mental consciousness to the stage of complete oneness with ‘ Satchidananda’ implies a positive effect on the part of man. Sri Aurobindo developed his own methods of making this effort and these are yogic methods. A brief discussion of these yogic methods is necessary for it will throw light on Sri Aurobindo as a transcendentalism Sri Aurobindo believed that through the process of Integral (Purna) yoga man can actively and effectively contribute to the evolutionary process and thereby quicken its finalisation. This Integral Yoga achieves a perfect synthesis o f Karma, Jnana and Bhakti Togas and leads to what Sri Aurobindo himself called “ The Sun-lit Path” . After a devoted practice (Sadhana) of this integral yoga a yogi can rise to that supramental plane where the supermind keeps shining bright with all its glory, light and power. Having risen to that plane the yogi will draw that light and power in his own consciousness. He will then come back or descend to that material plane from where he had risen, and will make himself the instrument through which the supramental or the light and the power that he has drawn within himself will act towards the spiritual evolution of thef earth-consciousness. This was what Sri Aurobindo is said to have performed. Through his intense endeavour he could succeed in raising himself to that supramental plane.

14

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

Two features of Sri Aurobindo’s yoga are particularly remarkable. They are that Sri Aurobindo’s yoga is not) individualistic but humanistic and that it strikes a final and satisfactory synthesis between Spirit and Matter. Salvation for the whole race or for the entire humanity and not only for an individual, is the goal that Sri Aurobindo’s yoga aspires for. It asserts that Matter is not the opposite of Spirit. Matter and Spirit are in fact two things at different stages in the same evolutionary process. Matter stands at the primary stage and evolves in the final stage into Spirit. Thus, indirectly, Sri Aurobindo’s yoga also strikes at a perfect synthesis between the western materialistic culture and spiri tualistic culture of India. Thus D. L. Murray rightly comments ‘ Sri Aurobindo is not an armchair philosopher but........... a new type of thinker, one who combined in his vision the alacrity of the west with the illumination of the East. m SRI AUROBINDO AS A MAN OF LETTERS Apart from politics, philosophy and yoga, Sri Aurobindo’s creative genius flowered simultaneously in literary fields such as poetry, literary criticism and drama. His writings reflect his political, philosophical and religious views. His patriotism served as a major influence on his writings. We know that the letters of his father, particularly those in which he complained of the maltreatment and insults heaped upon the Indians by the Englishmen and denounced British Govern ment as a heartless government, were the first to stir the hidden embers of nationalism in his heart. They drew him towards the Indian Majlis and the Lotus and Dagger Society, which was a secret party working for the liberation of India. The Irish patriotic movement too greatly influenced him. The life of the great Irish nationalist leader, Charles Steward Parnell, was a great source of inspiration to him. These early formative influences besides shaping his future career moved him emotionally and on many occasions found expression in his early poems. One such occasion was provided by the death

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

15

of Parnell in 1891. The poem that he wrote on his death ‘ Charles Stewart Parnell’ and the one entitled ‘ Hie Jacet (Glasnevin Cemetery) ’ amply demonstrate the patriotic bent of his mind and the inspiration drawn from the Irish patriotic movement. It is true that in England he wa3 brought up strictly in a purely European environment and had intensively and extensively studied Greek and Latin classics. His early poems, quite naturally, reveal deep influences of his Greek and Latin scholarship. They are replete with names, allusions and images drawn from Greek and Latin classics. The very title, Songs to Myrtilla, of the collection of his early poems written in England, is an example of this. But immediately after his return to India he plunged himself into a study of Indian languages and classics. At Baroda he learned Sanskrit and read the Vedas and the Upanishadas in the original. He also learned some modern Indian languages, specially, Marathi, Gujarati and Bengali. He was thus able to assimilate the spirit of Indian culture and civilization in a very short period. His later poems are replete with allusions from the Vedas, the Upanishadas and the Puranas and are thus a true expression of the genius of India. His poetic creations with their ‘ vividly worded vision’ and ‘ expressively rhythmed emotion’" have ushered in our world ‘ a new vedic and upanishadic age of poetry’." They are the creations of a mystically and spiritually inspired consciousness, and they present a subtle and rhythmic elucidation of the relationship, both existing and what should be, between the Mind and the Supermind. They are prophetic illustrations of the processes through which the Divinity shall be manifesting itself in the earth-body. In them we find a vision of the past, a knowledge of the present and a peep into the future. A single dominant motive, namely, man’s aspira tion for the higher and more divinely fulfilled life here and now, seems to run in all the works of Sri Aurobindo. In TJrvasie and Love and Death he speaks of the love that defeats death. Baji Prabhu presentB that unconsiderable

16

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

pressure. Poems like Who, The Bishi and The Birth of Sin, etc., are unique poetical expression of the mystical Sin*, etc., are unique poetical expressions of the mystical experiences of a great yogi. The rapidly growing poetical career of Sri Aurobindo reaches its culmination in Savitri. It is his magnum opus. It is cosmic in character and can be placed among the great epics of the world. K. D. Sethna says that it ‘ brings out living symbols from the mystical planes— a concrete contact with the Divine’s presence. Even when realities that are not openly divine are viewed, the style is of a direct knowledge, direct feeling, direct rhythm from an inner or upper poise..........m It is great also because it presents a vision which is interpretative and inspiring. Sri Aurobindo is also a great prose writer. The Future Poetry, The Synthesis of Yoga, The Human Cycle, The Ideal o f Human Unity are some of his important prose works. The Futwre Poetry is a significant work of literary criticism. In it Sri Aurobindo gives new directions and dimensions to the norms of literary criticism. New literary theories are pro pounded and illustrated in this book. About the methods of understanding and appreciating poetry Sri Aurobindo writes : In poetry as in everything else that aims at perfection, there are always two elements, the eternal and the time element. The first is what really and always matters, it is that which must determine our definite appreciation, our absolute verdict or rather our essential response to poetry.*1 About Elizabethan poetry he writes :— Elizabethan poetry is an expression of this energy, passion and wonder of life, and it is much powerful disorderly and unrestrained than the corresponding poetry in other countries, having neither a past traditional culture nor an innate taste to restrain its extravagances." Explaining his conception of the dramatic poetry, he writes : Dramatic poetry cannot live by the mere presentation o f life and action and the passions, however truly they may be portrayed or however vigorously and abundantly. . . v .

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

17

It most have, to begin with, as the fount of its creation or in its heart an interpretative vision and in that vision an explicit or implicit idea of life; and the vital presenta tion which is its outward instrument, must arise out of that harmoniously, whether by spontaneous creation, as in Shakespeare, or by the compulsion of an intuitive artistic will, as with the Greeks." Countless statements, comments, definitions and literary theories such as those quoted above fill the pages of this great book of criticism and they impress us by their aptness and pointedness. His prose style is always remarkable for the forcefulness of its expression and strength of conviction. It has speed and spontaneity and it changes with the change in themes. Sometimes it is simple, sometimes it is complex, some times it is metaphorical and makes abundant use of mythological and epical reference but nowhere does it fail to drive in the point it carries. His letters and speeches touch upon a surprisingly large number of topics such as nationalism, politics, philosophy, sociology, world unity, the ancient scriptures like the Vedas, the Upanishadas, the Gita. Indian Art, literature and general culture, poetry, plays, literary criticism, etc. Of his letters to his wife only three survive. The first letter gives us a knowledge of the aspirations, dreams and desires of Sri Aurobindo, the second records his doubts and anxieties and the third enunciates the final resolve, the absolute surrender of the self to the service of humanity and in the hands of the Omnipotent." Wit and humour too characterise Sri Auro bindo ’s prose. In a letter Sri Aurobindo writes ‘ sense of humour ? It is the salt of existence. Without it the world would have gone utterly out of balance—it is unbalanced enough already— and rushed to blazes long ago’.” Yet these letters reflect Sri Aurobindo’s lofty thoughts. Commenting upon these letters Dr. Iyengar writes : They are written in somewhat less lofty and difficult style than his other more metaphysical works and yet they bear the stamp of luminous authenticity and are

18

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo charged with that High Wisdom which comes from the complete living in the spirit 's complete truth."

Even the minor sequences of The Arya, such as Commen taries on 1th* and Kena Upamshadas. The Hymns of the Artris, The Renammtee in India, A Rationalistic Critic on Indian Culture, Ideal and Progress, The Superman and Evolution, etc. deal with a multitude of diverse themes in a varied and attractive manner. Over and above these, there are his plays which illustrate his versatile genius all the more. Perseus the Deliverer, Vasavadutta, Rodogune, The Viziers of Bassora, Eric and the incomplete Prince of Edur, are all embodiments of the dramatist’s vision of man labouring continuously to achieve an almost absolute freedom, freedom from ignorance, from disease, incapacity and death, and to establish a blissful state of divine living. All these are poetic dramas. Rodogune is a tragedy. The Viziers of Bassora is a dramatic romance. Perseus the Deliverer is a serious drama. Vasavadutta and Eric are romantic comedies. Sri Aurobindo thus created his own literary world which has both wealth and variety. He wrote philosophical ( The Life Divine), psychological (Synthesis of Toga), sociological ( The Human Cycle), political (Ideal of Human Unity), critical (The Future Poetry), poetical (Two volumes of Collected Poems and Savitri), and dramatic (five complete plays and one incomplete play) works. Apart from these he left a huge stock of letters, speeches, messages, essays, transla tions of and commentaries on some of the Upanishadas such as Isha, Kena, Katha Mundaka, etc., exhaustive commentaries on the Oita in the form of Essays on Oita and an English rendering o f Kalidasa’s drama Vikramorvasi under the title The Hero and the Nymph. Whatever he wrote bore the imprint of his profound and versatile genius. In all of them we find the high watermark of Aurobindonian perfection. They all seem to point to us that even in this ‘ Age of despair’ there is

Sri Aurobindo : A Versatile Genius

19

nothing to feel frustrated find 9 very high level of perfection and piose is still within the reach of humanity. Sri Aurobindo was indeed an intellectual prodigy and a versatile genius. NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. See Appendix of Longer Notes, Note A, p. 232. 2. K.R.S. Iyengar: Sri Aurobindo (Calcutta, 1950), p. 157. 3. Shri Arobindo : Essays on Gita, vol. II (Pondicherry, 1928), p. 484. 4. Shri Aurobindo : Collected Poems and Plays, vol. II (Pondi cherry, 1942), p. 122. 5. Ibid., p. 286. 6. See Appendix of Longer Notes, B. p. 210. 7. Sri A urobindo: Collected Poems and Plays, vol. I ll Pondi cherry, 1942), p. 126. 8. Ibid., p. 297. 9. Sri Aurobindo : Savitri, 3rd ed. (Pondicherry, 1970), Book 9, canto 1, p. 577. 10. Sri Aurobindo: On himself and the Mother (Pondicherry, 1953), p. 26. 11. Karan Singh: Prophet of Indian Nationalism (Bombay, 1970), p. 61. 1‘2. Sri Aurobindo: Speeches of Aurobindo Ghosh (Pondicherry, 1969), p. 101. 13. Ibid., p. 140. 14. K.R.S. Iyengar: Sri Aurobindo (Calcutta, 1950), p. 155. 15. Sri Aurobindo: Speeches (Pondicherry, 1969), p. 6. 16. Quoted by S.K. Banerjee in his 'The Nation-Idea in our Early History’ Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual, No. 20 (Calcutta, 1961), p. 104. 17. Karan Singh : Prophet of Indian Nationalism (Bombay, 1970), p. 75. 18. Sri A urobindo: The Doctrine of Passive Resistance (Pondi cherry, 1966), pp. 83-84. 19. Sri Aurobindo: Speeches of Aurobindo Ghosh (Pondicherry, 1969), pp 133-134. 20. Ibid., p. 194. 21. A.B. Purani : Sri Aurobindo-Addresses on his Life and Teach• ing (Pondicherry, 1955), p. 38. 22. Karan Singh : op. cit, p. 70.

20

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

23. Sri A urobindo: The Life Divine, Part II (Calcutta, 1940), p. 656. 24. Ibid., pp. 985-984. 25. Sri Aurobindo : The Mother (Pondicherry, 1957), pp. 85*84. 26. Sri Aurobindo: The Life Divine (Calcutta, 1940), p. 1022. 27. D.L. M urray: ‘Sri Aurobindo’, The Times Literary Sup plement, 8 July 1944. 28. K.D. Sethna: The Poetic Genius of Sri Aurobindo (Bom bay, 1947), Prologue. 29. Ibid. 50. Ibid., p. 98. 51. Sri A urobindo: The Future Poetry (Pondicherry, 1955). p. 54. 52. Ibid., p. 88. 55. Sri Aurobindo: The Future Poetry (Pondicherry, 1955), p. 95. 54. See Appendix of Longer Notes, Note C, p. 210. 55. Quoted by K.R.S. Iyengar in his Sri Aurobindo: An Intro duction (Mysore, 1961), p. 5. 56. Sri A urobindo: Letters of Sri Aurobindo, 1st Series (Pondi cherry, 1960. Forward by Kishore H. Gandhi.

CHAPTER II

Sri Aurobindo’s Plays : A Note on Their Chronological Order

The number of available plays, written by Sri Aurobindo, is six. This number excludes two more plays, which, since avail able only in fragments, have not been considered. The word Available’ has been deliberately used here for it is known that in connection with Alipore Bomb Case, the police made a sweeping search of Sri Aurobindo’s house (on May 5, 1908 at about 5 a.m.) and took into its possession all the papers, connected or unconnected with the case, found in his house. The following quotation from K. R. S. Iyengar’s Sri Aurobindo gives a very vivid account of this seize : Accordingly, on May 5, 1908, at about 5 a.m., the Super* intendent, the Inspector and other police officers “ entered Aurobindo’s bedroom, and, on opening his eyes, he saw them standing round. Perhaps, he thought himself in the grip of a nightmare, gazing an apparitions in the halflight of dawn. However, he was not left in suspense long........After securing Aurobindo, his bedroom was searched. ‘ Search’ is not the word for it. It was turned inside out. The ransacking went on for three hours. . . . ” ...........As a result of the search, the officers found a number of essays, poems, letters, etc., which they took away from the house. . . . .* The entire bulk of the papers thus recovered from his house

21

22

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

was thrown into the oblivion of the Record Room o f the Court. They were taken to be lost for all practical purposes. But in 1949, by a happy coincidence, most of them were recovered and from among the papers manuscripts of two complete plays written by Sri Aurobindo, were salvaged.* Thus it may not appear incorrect to apprehend that the papers which could not be found out might have contained manuscripts of some more plays which, hence, remain unavailable to us. This belief is further strengthened by the fact that the manuscript of the translation of Kalidasa’s Meghduta by Sri Aurobindo still remains traceless. From the point of view of the date or year of composition The Viziers of Bassora appears to be the earliest draWmtic work of Sri Aurobindo. According to the Publisher's Note attached to the book : This drama is one of the earlier works of Sri Aurobindo on a major scale. Written in Baroda,. it has a curious history attached to it. Sri Aurobindo seems to have had an especial fondness for this youthful creation of his and so it was particularly mentioned in the Introduction to the Collected Poems and Plays as one of the two works— the other being a translation of Kalidasa's Meghaduta (Cloud-Messenger)—that had been lost in the course of the many turmoils and vicissitudes that a busy political life had meant in India at the beginning of the century. The Kalidasa-manuscript is still untraced. But by a strange turn of destiny the drama, after it had lain buried in the Government archives for nearly fifty years, was recovered and saved— thanks to the alert curiosity of a record-keeper—just as it was being disposed of as waste paper. The note book in which it had been written was an exhibit in the famous Alipore Conspiracy Case,........ * The quotation given above makes it clear that thi* play must have been written some time between 1893 and 19061 for this period (i.e. between 1893 and 1906) of his life was spent in Baroda. Iyengar writes ‘ Sri Aurobindo was now in Baroda,

Sri Aurobindo** Hays and he spent the next thirteen years, from 1893 to 1906, in Baroda State S|er*ice’. 4 Prince of Sdur comes aext in line. The Publisher's Note attached to it is quoted below : This drama by Sri Aurobindo was written, as noted in the Ms., in 1907, that is to say, in th« very thick of the mael strom of his politieal activity........... * It is an incomplete play and is available only in three acts. From a perustal of the last page of the manuscript of the play printed in facsimile and attached to the play, it appears that the third act was completed by February 12, 1907. We know that in August 1906 he accepted the post of Principalship of the Bengal National College and came to Calcutta leaving the service of Baroda State for good. Iyengar writes, ‘ During the next few months’, i.e. after August 1906, ‘ Sri Aurobindo was in indifferent health; he took leave from the National College again and again, and spent four or five months between Decem ber 1906 and April 1907, at Deoghar, with the exception of about ten days in December-January for Congress meetings in Calcutta’.' Thus it can be surmised that at least a portion of this play was written at Deoghar and the rest might have been written in Calcutta. Perseus the Deliverer is the third in sequence. Iyengar notes that ‘ According to Mr. Nolini Kant Gupta, “ this drama was written somewhere between the end of the nineties and the first years of the following decade” . It was first published serially in 1907 in the columns of the weekly edition of The Bandemataram.T Iyengar also writes that (Perseus the Deli verer, Sri Aurobindo’s great poetic play, began as a serial in the issue of June 30, 1907’.* This much is, thus, certain that the play was composed in Calcutta and completed before or during the year 1907. Eric is the fourth in sequence as it was written in Pondi cherry either in 1912 or 1913 This assumption again is based on the Publisher’s Note which mentions “ Eric was written in

24

th e Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

Pondicherry in 1912 or 1913” . It was certainly written in the Ashram at Pondicherry for between April 4, 1910, the day when Sri Aurobindo reached Pondicherry and December 5, 1950, the day of his death, he never, even for once, left Pondi cherry. Vasavadutta was completed during the year 1915 or a little earlier. It was written at Pondicherry Ashram. The Publisher’s Note attached to this play runs as follows : Vasavadutta exists in several versions, not all of them complete. What seems to be the last complete version has this note at the end. . . “ Revised and recopied between April 8 and April 17, 1916” . An earlier version has a similar entry at the end : “ Copied Nov. 2, 1915— written between 18th and 30th October 1915. Completed 30th October. Revised in April 1916. Pondicherry” .10 The place and year of the completion of Rodogune is not known. It was first published in the year 1958 in Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual No. 17. But on the ground of its maturity of vision and perfection of dramatic craftsmanship the play can safely be argued to be the last play of Sri Aurobindo. Perseus the Deliverer was the first play to be published in book-form. It was published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry, in the ytar 1955. Thus it may be said that in book-form Perseus thi Deliverer too had a posthumous publication (it has already been mentioned that it was first published serially in 1907 in The Bandemataram). All other plays are posthumous publications. Vasavadutta, Rodogune, The Viziers of Bassora and Eric were first published in the issues of Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual in the years 1957, 1958, 1959 and 1960 respectively, In the same respective years subsequent ly they were reprinted in book-form by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press. Pondicherry. Prince of Edur, which first appeared in Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual (1961), has not as yet been published in separate book-form. A different version or rather the first version of the theme of Prince of Edur is also avail able. It is titled Prince of Mathura and it has two common

Sri Avrobindo’s Ptayt characters, namely, Torman and Canaca and other identical characters with different names. Only a fragment of the play i.e. Act I scene I is available. It has been printed for the first time in Collected Plays and Short Stories, Part two, Vol-7 published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. In this very volume are also printed fragments of two other incomplete playB namely The Maid in the Mill and the House of Brut These two belong to Sri Aurobindo’s early Baroda period. Only five scenes of the first act of The Maid in the MUl sub titled ‘ Love Shuffles the Cards A Comedy’ are available. Only one scene, an incomplete scene I of Act II, of The House of Brut is available. The available fragments of these two plays were first published in Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual, 1962 and they have been left out of the scope of this book. In this book, Sri Aurobindo’s plays have been studied in their above-mentioned chronological order. Such a scheme, it is hoped, will help us to have an idea of the development of Sri Aurobindo’s mind and art as a dramatist. It must, how ever, be remembered that we cannot be absolutely sure of the chronological order of Sri Aurobindo’s works, particularly his plays, for Sri Aurobindo wrote not to make a name by his writings, but to show humanity the nobler and higher paths of life. His works are born out of inspiration—an immense spiritual inspiration. In fact it was as he himself said, ‘ the voice of God”1 that he constantly responded to and translated into his writings. His was a noble and high soul that preferred doing its work silently. That is why we do not have any precise knowledge of his works nor did he ever bother with it. The only two certain statements that can be made about his works are that in all of them we find the watermarks of high perfection and that they are superb in thought, theme and diction and are intended to fulfil in some way the divine mission of human upliftment.

.

NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. K.R.S. Iyengar: Sri Aurobindo (Calcutta, 1950), p. 153. 2. For the story of the salvage-operation See Appendix o f Longer Notes, Note D, p. 211.

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo 5. Sri A urobindo: The Viziers of Basaora (Pondicherry, 1959), Publisher’s Note. 4. K.R.S. Iyengar: Sri Aurobindo (Cacultta, 1950), p. 29. 5. Sri A urobindo: ‘Prince o f Edur', Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual, Jayanti No. 20 (Calcutta, 1961), Publisher’* Note. 6. K.R^S. Iyengar: Sri Aurobindo (Calcutta, 1950), p. 112. 7. Ibid., p. 71. 8. Ibid., p. 119. 9. Sri A urobindo: Eric (Pondicherry, 1960), Publisher’s Note. 10. Sri A urobindo: Vasavadutta (Pondicherry, 1*957), Publi sher’s Note. 11. Sri Aurobindo: Speeches of Aurobindo Ghosh (Pondicherry, 1969), p. 88.

SECTION TWO

INTERPRETATION

\

I I iI i

CHAPTER III

The Viziers of Bassora

1 The Viziers of Bassora, the first dramatic work of Sri Aurobindo, was written in Baroda some time between 1893 and 1906. When Sri Aurobindo was taken into custody in connection with the Alipore Case, all his papers which included the manuscript of this play, were seized by the police. The manuscript remained untraced till the year 1951 when by a strange turn of events it was discovered among the records of the Alipore Case preserved in a steel cupboard in the retiring room of the District Judge. It is to be noted that in 1936 orders had been passed for the destruction of the records of the case but as a very especial case they were, although unofficially, kept in a corner of the Record Room from where they were transferred to a steel almirah in the retiring room of the District Judge. Sri Aurobindo took the manu script of the play as lost. He had a special fondness for this creation of his youth and so referred to it in the introduction to the Collected Poems and Plays. The plot o f The Viziers of Bassora is based on several stories, found in The Book of the Thousand and one Nights by Sir Richard Burton and fused in the crucible of the dramatist’s imagination. As for example in The Book of the Thousand and one Nights there is the ‘ tale of the Second 29

30

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

Eunuch, Kafur.1 in which such characters as Haroun al Rasheed, the Caliph of Bagdad, Jafar, his vizier, Kut al-Kutub, a slave girl, Mohammed bin Sulayman al-Zayni and Ghanim are found. The love story of Ghanim and the slave girl, Kut al-Kutub, bears some resemblance to the love story of Nureddene and Anice al-Jalice. In another story, ‘ The fifth voyage of Sindabad the seaman’* there is a reference to merchants going from Bassorah to Bagdad, and in yet another story. ‘ Ma’aruf, the cobbler and his wife Fatimah’,* adventures of Ma’aruf the cobbler and Princess Doonya are narrated. But all these stories separately do not bear much resemblance to the story of The Viziers of Bassora. It appears that Sri Aurobindo has picked up only hints and characters from the various stories of The Book of the Thousand and one Nights and created his own almost an original story. As a matter of fact the source material of this play suffers a sea-change in Sri Aurobindo’s artistic creation. Mohamad bin Suleyman of Zayni is the cousin of Haroun al Rasheed, the Caliph of Bagdad. He has two viziers, Al fazzal Ibn Sawy and Almuene bin Khakan. The people of Bassora know Alfazzal as a noble and kind vizier and Almuene as a wicked and cruel vizier. Alfazzal’s family consists of his wife Ameena, his niece Doonya and his son Nureddene. He leads a happy family life. Almuene’s family consists of his wife Khatoon and his hunchback son Fareed. Once Fareed visits the slave market. He sights there a slave girl named Anice al-Jalice and decides to buy her. He and his father underbid for her and try to lift her from the market forcibly. Just at that moment Alfazzal enters the market. He offers a suitable price for the slave girl and buys her for the king’s harem. He brings the girl to his house and asks his wife to keep her in hiding away from the prying eyes of Nureddene. Doonya. his niece, eleverly manages to let Nureddene see. Anice. Nureddene falls in love with her at first sight. Alfazzal comes to know of this love and permits them to be united in holy wedlock. Doonya is married to Murad, a Turk Captain of

The Viziers o f Bassora

31

police in Bassora. Alfazzal then leaves for ‘ Bourn’ under the orders o f Haroun al Raaheed, tbt Caliph, to have talks on behalf o f the Caliph with the emperor of ‘ Roum’ (.Rome). In his absence Almuene trie# to make capital out of the fact that Alfazzal had got his son married to Anice al-Jalice, a slave girl bought for the king’s harem. He attempts to ruin Al fazzal and his family by misrepresenting the facts before the king and succeeds to a great extent in his attempts. Orders are given to arrest Nureddene and Anice. But before the order could be executed, they, with the help of Ajebe, Almuene ’« nephew, flee away to Bagdad. In their absence Fareed tries to kidnap Doonya but in the ensuing brawl he is killed by Murad. In Bagdad Nureddene and Anice chance to enter the pleasure garden of Haroun al Rasheed. Shaikh Ibrahim is the Superintendent of this garden. He is ensnared by Anice’s >eauty and lets the pair celebrate their presence in the pleasure garden of the Caliph. Her song and face draw the attention of the Caliph, who disguises himself as a fisherman and rushes to the garden. He meets them and is very much impressed by them. He promises to help them. Nureddene, with a letter from him to the king of Bassora, leaves for Bassora. Anice is left in his care. In Bamora Almuene’g wickedness acts quickly and Nureddene is arrested and put on the scaffold. But the army of the Caliph enters the city just in the nick of time to save Nureddene’s life. King al-Zayni and vizier Almuene are punish ed. Nureddene is made the king of Bassora and is united with Anice, his father, mother and Doonya.

2 The play The Viziers of Bassora can be said to be a study in contrast. The two viziers, Alfazzal and Almuene, are them selves diagonally opposed characters : if Alfazzal is a good kindly man, Almuene is a thoroughly wicked fellow. A s .a matter of fact the main characters of the play can be classified under two headings, i.e., (1) characters who are essentially good, and (2) characters who are basically evil. Haroun al Rasheed, Alfazzal, Nureddene. Anice al-Jalice, Ameena,

32

The Dramatic A rt of Sri Aurobindo

Khatoon and Doonya are essentially good characters whereas Fareed, Almuene and al-Zayni are evil characters. Haroun al Rasheed is just, mighty and angelic. He is ‘ Allah’s vicegerent’* and it is his duty— . . ., to put down all evil And pluck the virtuous out of danger’s hand.* He is the symbol of enlightened monarchy. The wrong doers find in him a terrible monarch and receive dire punishment at his hand such as king al-Zayni and Almuene receive : Sultan al-Zayni not within my realm Shall Kings like thee bear rule. Great though thy crimes, I will not honour thee with imitation, To slay unheard.* The noble characters, such as Anice and Nureddene, oppressed and tortured unjustly, find in him a true friend and a protecting and guiding spirit. As a symbol of the high seat of justice he remains ever alert to find out and root out corruption and injustice and to promote nobility, love and benevolence : This is the thing that does my heart most good To watch these kind and happy looks and know Myself for cause. Therefore, I sit enthroned, Allah’s vicegerent, to put down all

They told me that my hair was a soft dimness With thoughts o f light imprisoned in ’t; the gods, They said, looked down from heaven and saw my eyes. Wishing that they were heaven. They told me, child, My face was such as Bramha once had dreamed of But could not—no, for all the master-skill That made the worlds—recapture in the flesh So rare a sweetness. They called my perfect body A feast of gracious beauty, a refrain And harmony in womanhood embodied.' She is ‘ a feast of gracious beauty, a refrain/And harmony in womanhood embodied’. She has not only a ‘ rare sweetness’ and ‘ a perfect body’ but also a firm grip over the hilt of sword. She is a maiden of unique self-confidence and believes that she can cleave out her own way, with the help of her sword, through the tangled hedge of life. That is why she asks Nirmol Cumary to give her sword to her : Give me my sword with me. I ’ll have a friend To help me, should the world go wrong.1 Except herself and her sword she does not believe in anything else for this world is not what it appears to be ;

f

Prince of Edur

55

But I ’ll believe myself and no one else Except my sword whose sharpness I can trust Not to betray me." She, thus, imbibes that brave spirit and self-confidence which are the special features of Rajpoot womanhood. The nobility o f her character becomes the more impressive, in the background o f her father’s character. When she comes to know of the plots of her father, mother and Visaldeo, she accepts the challenge : Come, girls, make we ready For this planned fateful journey*

1

Her letter to Bappa reveals, all at once and all at one place, her strength and weakness, her modesty, her dreams and desires, her sense of humour and her pride and prejudice. The following lines, from her letter, will illustrate the point : Thou hast carried me moat violently to this thy inconsider able and incommodious hut, treating the body of A princess as if it were a sack of potatoes........... Thou hast compelled and dost yet compel me, the princess of Edur, by the infamous lack of women servants in thy hut, to minister to thee, a common Bheel, menially with my own royal hands, so that my fingers are sore with scrubbing thy rusty sword which thou hast never used yet on anything braver than a hill jackal, and my face is still red with leaning over the fire cooking thy most unroyal meals for thee, and to top these crimes, thou hast in thy robustious robber fashion taken a kiss from my lips without troubling thyself to ask for it. . . * She is a royal child subjected to the pressure of politics by no less a person than her own father. She is royal by birth, by bodily charm and by temperament. She desires to be nobly possessed by a noble person. That is why her heart surrenders before the imposing personality, sincere love and heroism 6f Bappa but her mind refuses to obey her heart. She, then, invites her other suitors, Torman and Pratap, to win her from Bappa’s hand. It is only when Bappa defeats both of them and establishes absolute supremacy of his sword thait she Surrenders herself to his arms ;

56

The Dramatic A rt of Sri Aurobindo Indeed it was Your high resistless fortune. 0 my king, My hero, thou hast 0 ’erborne great Ichalgurh; Then who can stand against thee? Thou shalt conquer More than my heart.10

Comol Cumary is Sri Aurobindo’s version of ‘ the goddess of the forest’, i.e. Vandevi. She herself says, ‘ I have been wandering in my woods alone/Imagining myself their mountain queen’. All the woodland-flowers, birds, squirrels and peacocks worship and adore her. The myriad voices of the forest announce her to be their goddess. She understands the ‘ leafy language’ of the forest. The trees, the waters, the pure soft flowers ‘ take voices and speak to her’ : I have been wandering in my woods alone Imagining myself their mountain queen. 0 Coomood, all the woodland worshipped me ! Coomood, the flowers held up their incense-bowls In adoration and the soft-voiced winds Footing with a light ease among the leaves Paused to lean down and lisp into my ear, Oh, pure delight................. They told me all these things,— Coomood, they did, Though you will not believe it. I understood Their leafy language.11 Coomood Cumary, the daughter of Rana Curran by a concubine, is a playmate of Comol Cumary and also her friend. She is always with Comol Cumary sharing both her pleasure and pain : Let them keep Our palanquins together. One fate for both, Sweetheart.1*

,

Like Comol Cumary she, too, is a girl of self-confidence and is courageous enough to face any adversity but she is more witty and lighthearted than Comol Cumary. In this regard she is very much similar to Doonya of The Viziers of Bassora. She is less sentimental and more practical than Comol. Once when Comol is deeply fascinated by the beauties of Nature and ex presses her desire never to return to Edur because, it has no

Prince of Edur

57

natural scenes and sights and becomes almost oversentimental it is Coomood who restrains her and reminds her of her duties and responsibilities. She is a good conversationalist and her remarks are often very apt and striking. Her reply to Bappa, when he questions her about Comol Cumary, may be quoted as an example : Bappa : Can you tell Why she has set these doughty warriors on me, Coomood f Coomood Cumary : You cannot read a woman’s mind. It’s to herself a maze inextricable Of vagrant impulses with half-guessed tangles Of feelings her own secret thoughts are blind to.“ Nirmol Cumary* the daughter of Haripal and Comol Cumary’s friend, is a very sprightly character. She is a happy-go-lucky type of a maiden and is full of wit and humour. She has the capacity to make light even the most tense of moments. Even when she is surrounded by the Bheels and put under arrest she remains playful and gay. Her dialogue with Sungram is witty and creates much humour : Sungram : Must we follow in the same order ? Nirmol Cumary : By your leave, no. I turn eleven stone or thereabouts. Sungram : I will not easily believe it. Will you suffer me to test the measure f Nirmol Cumary : I fear you would prove an unjust balance; so I will even walk, if you will help me over the rough places. It seems you were not Krishna after all ? Sungram : Why take me for brother Balram then. Is not your name Revaty?

58

The Dramatic A rt of Sri Aurobindo

Nirmol Cumary : It is too early in the day for a proposal. Positively I will not say either yes or no till the evening. On, Balram ! I follow " Her dialogues contain images drawn mostly from the day-today life and serve two purposes—first, they vivify certain characters by throwing light upon them and second, doubly interpret certain situations. Let us consider these lines for example : He will not listen. These scythians stick to their customs as if it were their skin; they will even wear their sheep skins in midsummer in A gra.1* or I would not greatly mind. They say he is as big as a Polar bear and has the sweetest little pugnose and cheeks like two fat pouches.1* or Where, I hope, justice will have set right the balance be tween his nose and his cheeks. Girls, we are the prizes of this handicap, and I am impatient to know which joekey wins.” Her funny sayings, similes and metaphors counterbalance the heaviness created by Rana’s decision to give away his daughter to the Prince of Cashmere in marriage. Bappa is a gallant young prince. He is a great warrior and possesses that largeness of heart which can easily forgive and release the enemies : ’Tis not my wx>nt to slay my prisoners, Who am a Rajpoot.1* By birth he is a Rajpoot but because of certain unavoidable circumstances he is compelled to live among the Bheels. He is not a mean-minded person and can appreciate the noble qualities of his enemies. He bravely challenges Pratap to a duel : Let us in the high knightty way decide it. Deign to cross swords with me and let the victor Possess the maiden.1*

Prince of Edur

59

H e defeats him, shakes hand with him, tends his wounds and offers him cordial hospitality : Pratap, I could but offer A rude and hill-side hospitality* H e has a personality which makes him loved by friend and foe alike. Lion and god images are used to vivify him through o u t the play. He is a ‘ young lion’, a ‘ hungry lion’ and a ‘ bright lion*. He has a ‘ god like brain’ and Pratap tells him : Young chieftain. Thou bear’st a godlike semblance,*1 H e is a ‘ godlike combatant’ and is a ‘ springing stem' : O thou springing stem That surely yet will rise to meet the sun !** A fte r his duel with Pratap he gets overdrunk with the wine o f victory and of love and hence from now onward his language becomes ornamental, impassioned blended with sensuousness and rich in imagery. Take for example these lines : Rebel against your heart ! You’re trapped in your own springs. My antelope ! I*ve brought you to my lair. Shall I not prey on you? Kiss me.* Bappa, thus, is a noble and knightly soul. In Sbri Aurobindo’s plays, as in Shakespeare’s, life has been lavished upon the minor characters as well. Rana Curran is an opportunist. He can go to any limit to get his personal causes well served. Coomood Cumary aptly remarks about him : . . . the brain’s too politic. A merchant’s mind into his princely skull Slipped in by some mischance.*4 Rana is an extremely selfish man and betrays his nature in the very language he uses. His language, mostly, is full of such words and phrases as ‘ giant arms’, ‘ mongrel roots’, ‘ as narrow as glen’, ‘ penniless pride’, ‘ ant-hill’, ‘ mountaiu tarn’ etc. The way he admonishes his queen reveals his low mental make up :

60

The Dramatic A rt of Sri Aurobindo You are all As narrow as the glen where you were born And live immured. No arrogance can match The penniless pride of mountaineers who never Have seen the various worlds beyond their hills. Your petty baron who controls three rocks For all his heritage exalts himself O ’er monarchs in whose wide domain his holding’s An ant-hill,*

In his talks with his daughter he attempts to give his base plans and vile intentions the clothing of a proverb image : ’tis the stars decree it That in their calm irrevocable round Weave all our fates." Torman is the Prince of Cashmere. He, though the prince of a big state, is a coward and a hypocrite. He very much boasts o f his bravery and continually talks of himself as a great warrior but at the very first confrontation with the Bheels in the forest of Dongurh becomes ‘ a mass of terrorstricken flesh’.* Canaca, the jester of the court of Torman, provides most of the fun and frolic of the play. His excessive fondness for food finds expression in his images chiefly com prising food articles and diseases like indigestion and dysentery. Prithuraj is a common soldier and his thoughts do not rise above the common commonality. His ‘ mint and money* imagery — Think how ’t will help our treasury. The palanquins alone must be a mint Of money and the girls’ rich ornaments Purchase half Rajsthan. “ —reveals his weakness for money. Sungram is a Rajpoot warrior and the captain of Bappa’s army while Kodal is a Bheel soldier. Kodal’s vocabulary consists of such words as ‘ plain-frogs’, ‘ dog-box’, ‘ croak’ and ‘ rogues’ etc. The differ ence between Sungram and Kodal is the difference between a Rajpoot and a Bheel and this is amply illustrated through their dialogues : Sungram : Release her, Kodal, lay not thy Bheel han, (The Wavcrley Book Company Ltd., L on don ,...) p. 128.]

r

Appendix of Longer Notes

215

Perseus Legend—Oxford Companion to English Literature version—‘Perseus the son of Zeus and Danae. . . Polydectes having received the mother and child became enamoured of Danae. Wishing to get rid of Perseus, Polydectes sent him to fetch the head of the Medusa.. .thinking that he would be destroyed. But the gods favour ed Perseus. Pluto lent him a helmet that would make him invisible, Athene a buckler resplendent as a mirror.. ..and Hermes the talaria or wings for the teat. He was thus able to escape the eyes of the Gorgons (who turned what they gazed on to stone), and cut off the Medusa’s head. Continuing his flight, he came to the palace of Atlas...who recollecting an oracle that his garden would be robbed of their fruit by a son of Zeus, violently repelled him. Thereupon Perseus showed him the Medusa’s head and Atlas was immediately changed into a mountain. In his further course, Perseus discovered Andromeda. . . exposed on a rock to a dragon that was about to devour her. Having obtained from Cepheus, her father, the promise of her hand, Perseus slew the dragon. But Phineus, Andromeda’s uncle, attempted to carry away the bride, and, with his attendants was changed into stones by the Medusa’s head. Perseus then returned to Seriphos, just, in time to save Danae from the violence of Polydectes, whom he like wise destroyed. Perseus now restored to the gods the arms that they had lent him and placed the Medusa’s head on the aegis of Athene, where it is usually represented. He subsequently embarked to return to his native country. At Larissa he took part in some funeral games that were proceednig, and when throwing the quoit had the mis fortune to kill a man in the throng who turned out to be Acrisius his grandfather, thus fulfilling the prophecy concerning Danae’s son. He refused to ascend the throne of Argos to which he became heir by this calamity, but exchanged this kingdom for another and found ed the new city of Mycenae.’ [Sir Paul Harrey, (ed.) : The Oxford Companion to English Literature (London, 1938), p. 168.] Note G Pallas Athene: The Greek goddess of wisdom, industry, and war, identified by the Romans with their goddess, Minerva. She was the daughter of Zeus and Metis and sprang fully grown and armed from the brain of her father, who had swallowed Metis when pregnant, fearing that the child would be mightier than he. Athene quarrelled with Poseidon for the right of giving name to the Cecropia. The assembly of the gods settled the dispute by promising the reference to whichever gave the more useful present to earth. Thereupon Poseidon struck the ground with trident, and a horse was sprang up. But Athene produced the Olive, was adjudged the victor and called the capital Athene. Her other name was Pallas, which signifies brandishing’ (her spear) [Sir Paul Harrty (ed.) : op. cit., p. 46.] Note H Odin—Among the andent gods of Scandinavian mythology, Odin, Wotan or Woden was considered to be the highest and holiest.

216

The Dramatic Art of Sri Aurobindo

As all the gods were supposed to be descended from him he was surnamed All father; and he and Frigga, his wife and queen, occupied the highest throne in Asgard, their city in the clouds. T o obtain his great power, Odin had visited Mimir, an old giant who guarded the sacred “ fountain of all wit and wisdom" in whose depths the future was clearly mirrored. Mimir had refused to let him drink unless he would give one of his eyes in exchange. Odin did not hesitate to pluck it out, and Mimir kept the eye in pledge, sinking it down into the fountain, where ft shone with a mild lustre. The eye that remained to Odin symbolised sun, the submerged one the moon. According to legend Odin created men and put them on the earth, teaching them to fish, hunt, and till the soil. He also taught them to fight and would occasionally take part in their battles... G. Stowel and J. E. Mason (ed.). op. cit., Vol. 5, p. 500. N o te I

Thor—‘Ages ago, according to myths of northern Europe there lived a powerful god named Thor, son of Odin. It was he who chas ed away the frost and called gentle winds and warm spring rains to release the earth from ice and snow. The lightning’s flash was his mighty hammer. Mjolnir, hurled in battle with the frost giants, and the rolling thunder was the rumble of his fiery goat-drawn chariot. He is akin to Donar, the Teuton thunder-god. Marriages, burials and civil agreements were made secure and hallowed by Thor’s hammer. Thor was a good-natured, careless god, always ready for adven ture, and never tired of displaying his enormous strength. He could shoulder giant oaks with ease and slay bulls with his bare hands. For sport he sometimes rode among the mountains, hurling his hammer at their peaks and splitting them in two. G. Stowel & J. E. Mason, (ed.), op. cit. vol. 7, p. 270. N o te J

Eric—‘a legendary king of Sweden, who could control the direc tion of the wind by turning his cap.—Sir Paul Harrey, (ed), op . cit., p. 264. Another king bearing the same name, i.e. Eric (1533-1572), actually ruled Sweden, but he was a king of illrepute. He was ‘the only son of Gustavus and Catherine of Saxe-lan en burg. He be came king in 1561 and owing to his morbid fear of the nobility, he gave confidence to Govan Persson—an upstart Having quarrelled with and imprisoned the royal Duke John, Eric harrased the aristo cracy and finally in 1566 imprisoned many of them at Uppsala.......... Two years later Eric’s insanity was so apparent that a committee of senators was appointed to govern the kingdom and finally in September 1568 he was replaced by the royal Duke John who became John III/— \Encyclopaedia Brittanica vol. EMW to EXTR, (The Ency clopaedia Brittanica Co. Ltd., London, 1968), p. 683.]

Appendix of Longer Notes Note K Aslauga’s Knight, ‘a romance by De la Motle Foque’ (the author of ‘ Undine’, ..........) translated by Carlyle in German Romance. Aslauga was the daughter of Sigurd and wife of Ragnar Lodbrog. The Knight Froda, long afterwards reading of her, elects her as the lady of his heart and his helper in fight and song. Aslauga appears to him from time to time and controls his destiny, and finally carries him off to the land of spirits. [Sir Paul Harrey, (ed.) : Op. cit., p. 43.] Note L Brihat-Katha Story

:

(i) Pradyota Mahasegu is given as the ruling king of Magadha. Padmavati is said to be his daughter. (ii) Yougandharayana goes to the Magadha Kingdom disguised as a Brahmin. Vasavadutta and Vasantaka are with him. Vasava dutta is given out as his daughter by Yougandharayana. (iii) Udayan’s visit to Magadha is occasioned by the invitation to accept the hand of Padmavati. The marriage is supposed to be previously planned by Yougandharayana. (iv) While at Magadh, Udayana suspects the identity of Avantika by the particular mode of weaving the garland. (v) The revelation of Vasavadutta is done by agency. The final reunion takes place in Lavanka.

a supernatural

A. Bhasa’s changes: (i) Mahasegu is the king of Ujjayini. The ruling kingof Magadha is Darshaka and Padmavati is his sister. (ii) Yougandharayana is disguised as a wandering ascetic. Vasa vadutta is shown to be his sister. Vasantaka, the jester, remains with Udayana. (iii) Udayana reaches Magadha in his distraction. The marriage with Padamavati comes off naturally. It is predicted by the Sooth sayers and subserves a political purpose. (iv)

The rtunion takes place in Kaushambi, Udayana’s capital. [G. K. Bhat: Svapna Vasavadutta (The Popular Book Store, Surat, 1952) ,p. 7].