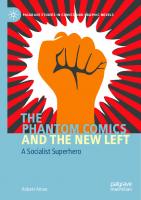

Superhero Culture Wars: Politics, Marketing, and Social Justice in Marvel Comics 9781350148635, 9781350148642, 9781350148673, 9781350148666

The reactionary Comicsgate campaign against alleged “forced” diversity in superhero comics revealed the extent to which

342 92 2MB

English Pages [209] Year 2021

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Cover

Contents

Acknowledgments

List of Abbreviations

Introduction: Mockingbird and Milkshakes: Comicsgate, Identity, and the Politics of Marketing in an Age of Outrage

1 From Stan’s Soapbox to Twitter: Politics and Story-Telling in the Marvel Universe

2 Diversity Done Right? Miles Morales and Kamala Khan

3 “Captain America Is Black and Thor Is a Woman”: Gender- and Race-Bent Mantle Passing in Marvel’s All-New, All-Different Campaign

4 Rethinking Secret Empire: Writing and Marketing Political Comics in an Age of Rising Fascism

Conclusion: Marvel Legacy and Fresh Start: Selling (and Selling Out) Progressive Politics

Works Cited

Index

Citation preview

Superhero Culture Wars

ii

Superhero Culture Wars Politics, Marketing, and Social Justice in Marvel Comics Monica Flegel and Judith Leggatt

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Copyright © Monica Flegel and Judith Legatt, 2021 Monica Flegel and Judith Legatt have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. vi constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Eleanor Rose Cover images © Getty Images All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: HB: 978-1-3501-4863-5 PB: 978-1-3501-4864-2 ePDF: 978-1-3501-4866-6 eBook: 978-1-3501-4865-9 Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments vi List of Abbreviations vii

Introduction: Mockingbird and Milkshakes: Comicsgate, Identity, and the Politics of Marketing in an Age of Outrage 1 1 From Stan’s Soapbox to Twitter: Politics and Story-Telling in the Marvel Universe 17 2 Diversity Done Right? Miles Morales and Kamala Khan 55 3 “Captain America Is Black and Thor Is a Woman”: Gender- and Race-Bent Mantle Passing in Marvel’s All-New, All-Different Campaign 89 4 Rethinking Secret Empire: Writing and Marketing Political Comics in an Age of Rising Fascism 123

Conclusion: Marvel Legacy and Fresh Start: Selling (and Selling Out) Progressive Politics 157

Works Cited 175 Index 193

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A book is never the sole creation of a single person, or even two people. We would like to acknowledge everyone who helped us in the process of writing, in particular the office of the Dean of Social Sciences and Humanities at Lakehead University, which provided us with a Summer Undergraduate Research Internship in 2017, and McKenna Boeckner, who filled that role and helped us with preliminary research into the Gabriel controversy. We would also like to thank Lakehead for providing us with sabbatical leaves in 2018–2019, without which this book could not have been completed in a timely fashion. We’d also like to give a shoutout to Hill City Comics in Thunder Bay for being our source for paper comics and the keeper of our pull-lists. We have many wonderful friends and colleagues who have supported us throughout this whole process. Many thanks go to Bry, Kyle, and Merk of the Zero Issues Comics podcast; our colleagues in the English department; Judith’s partner, Chris, who has no particular interest in superhero comics, but put up with our obsessive discussions of all things Marvel; and Monica’s family, who are too many, and as nerdy as they are plentiful. We would also like to thank the five cats who kept us warm and entertained as we wrote, and who were happy to distract us when we needed a break. Finally, thank you to the creators of Marvel comics, without whom we would not have these incredible texts to enjoy, critique, and analyze; you are the true superheroes of the comics industry.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ANADM CA CA:SR MCU SE IP

All-New, All-Different Marvel Captain America (1968–1996) Captain America: Steve Rogers Marvel Cinematic Universe Secret Empire Intellectual Property

viii

Introduction Mockingbird and Milkshakes: Comicsgate, Identity, and the Politics of Marketing in an Age of Outrage

In May 2016, Marvel Comics had good reason to celebrate with the positive press it was receiving for its new, diverse superheroes. In an article for The Guardian, entitled “Marvel Editor-in-Chief: ‘Writing Comics Was a Hobby for White Guys,’” Sam Thielman notes that Axel Alonso’s “Marvel looks very different: one of two Spider-Men is a biracial kid named Miles Morales, Thor is a white woman, one of the Captains America is a black man, Ms Marvel is Pakistani American and the Hulk is Korean American.” He then approvingly asserts, “All this happened with comparatively minimal backlash from notoriously tetchy readers, because Alonso and the company’s writing and editing teams have made changes carefully, switching costumes among established characters and stacking the deck with popular creators when the possibility of fan rage—which is always at least ambient—seems likely.” The publication date of the article allows us, with hindsight, to see this proclamation as woefully premature; in 2016, the comics world was not yet fully engulfed in the volatile culture clashes that have characterized the second decade of the twenty-first century. Unlike the culture wars of the 1990s, these new iterations are fueled by online culture and the mainstreaming of fandom, and include Gamergate in 2014, the 2015 Hugo Awards controversy, the Ghostbusters 2016 backlash campaign, and the

2

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

outcry over 2017’s The Last Jedi. By 2017, however, Marvel Comics would find itself at the center of its own controversy, as a series of fan backlashes, mainly focused on Marvel titles and creators, coalesced into a movement labeled “Comicsgate.” This protest featured all the elements of the previous clashes: conflicts between creators, critics, and fans that were connected to larger social/political issues, such as diversity; accusations that “political correctness” had infiltrated beloved fan texts and communities, threatening popular culture as a whole and the “quality” of fan texts in particular; the emergence of a cottage industry of outrage online, especially on platforms such as YouTube, which served as sites for organizing social-pressure campaigns that spread widely across other sites, such as Twitter and Reddit; and finally, coverage of the outrage in the mainstream media that sought to explain the significance of such movements to mainstream audiences, while producing comment sections that further fuel the conflict. The volatility of these clashes and their seeming repeatability with each new provocation of fan rage—a re-boot of She-Ra: Princess of Power, the casting of a woman as Doctor Who, comments by actor Brie Larsen on the lack of diversity in film criticism and the subsequent boycott of Captain Marvel—suggest that each iteration is not significant in and of itself, but rather that they speak to the zeitgeist of the present time: one marked by political polarization, a lack of civility in public debate, and an extreme blurring of the lines between popular and political culture.1 We want to make perfectly clear that, while these conflicts are often framed and understood as fan-driven, they differ greatly from the customary fan backlashes (such as anger over the cancellation of a beloved television show, or complaints about casting for film and television adaptations of books with large fandoms); their participants and influence extend far beyond the smaller circles of each specific fandom, and the focus is more often on reactionary politics than on the texts themselves. As Angela Nagle points out in Kill All Normies: The Online Culture War from Tumblr and 4chan to the Alt-Right and Trump, conflicts such as Gamergate, which originated within the online video-gaming community, included all kinds of people from critics of political correctness to those interested in the overreach of feminist cultural crusades. These brought in to the fold people like Christina Hoff Sommers, the classical liberal who started a video series called The Factual Feminist, which aimed to expose faulty statistics within feminism. Somewhere in the mix with the polite and light-hearted Sommers were also apolitical gamers, South Park conservatives, 4channers, hardline anti-feminists, and young people in the process of moving to the political far right without any of the moral baggage of conservatism. (24)

The election of a reality television star as the American president is the most obvious example, but YouTube personalities running for political positions in the UK also demonstrate this point.

1

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

3

So too Comicsgate, which provides the impetus for this book, went far beyond comics fandom proper (i.e., those who regularly produce, consume, collect, and discuss Marvel superhero comics). Online blogs that covered comics like The Beat, io9, and Bleeding Cool were certainly sources for coverage of debates about the politics of Marvel Comics, but the press it received in The Guardian, Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, and Vulture supports the opinion that “Most folks in the world of comics will tell you that Comicsgate isn’t even really about comics, per se, but rather an extension of the current political divide” (Jancelewicz). If Comicsgate isn’t really about comics, a point on which we largely agree with Jancelewicz, then in what way can it be employed to frame our discussion of Marvel Comics under Axel Alonso, and in particular his efforts to diversify and update its superhero stable? While Comicsgate may be a relatively circumscribed conflict affecting only a small number of comics producers and aficionados,2 it provides us with a means of analyzing the role identity politics—particularly as a specific marketing strategy that is either embraced or rejected by fans for political, as much as aesthetic, reasons—currently plays in Marvel Comics. Marvel Comics has long been a superhero genre powerhouse, responsible for iconic characters such as Spider-Man, Captain America, Iron Man, and Wolverine, and for teams such as the X-Men and the Avengers. It has also, with the launching of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in 2008, become a cultural touchstone far beyond the world of comics and comics fans. This, combined with the fact that Marvel has always portrayed its fantastical characters and worlds in ways that reflect the reality of “the world outside our windows”—one of the company’s catchphrases—makes an analysis of the role politics currently plays in this universe particularly relevant to battles over race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality in contemporary popular culture. Our book is not aiming to defend Marvel Comics from its Comicsgate critics, nor to argue from or for a centrist position in this debate. Rather, we want to analyze what it means to produce and consume overtly political creative texts at the present moment. This analysis entails addressing not just the obvious flashpoints of diversity and social justice both within the storylines of the comics themselves and as driving forces for the company and its creators, but also the complexity of “woke branding” in an age of extreme media concentration and how that branding should be taken into consideration when engaging in criticism of corporate-authored texts.

While the main conflicts of Comicsgate had died down by 2019, the hashtags “ComicsGate” and “SJW Marvel” were still popular on Twitter. Although the former seems mainly to be used to promote Kickstarter and Indiegogo sales of independent comics to those who associate with the movement, the latter is used to critique anything from Phase 4 of the MCU (Holdcroft) to Johnathan Hickman’s reboot of the X-Men (Benitez).

2

4

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

Shots Fired in the Culture War: Mockingbird and the Milkshake Crew One of the major characteristics of backlashes such as Comicsgate is an outsized response to trivial provocations.3 Or to be more specific, events or incidents are presented by social actors, in both good and bad faith, as affronts they must respond to in order to protect communities that present themselves as aggrieved and under attack. For example, what is often mentioned as the first inciting incident for Comicsgate was Joelle Jones and Rachelle Rosenberg’s cover for the eighth and final issue of Chelsea Cain and Kate Niemczyk’s Mockingbird (2016),4 which depicts the titular hero wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase, “Ask me about my feminist agenda.” The T-shirt captures the spirit of the comic itself: Mockingbird follows Bobby Morse’s adventures as someone intimately connected with, but also on the periphery of, the Avengers and the Marvel superhero community in general, and it is feminist in both content and style. Specifically, Mockingbird engages in gender commentary through its depiction of Bobbie negotiating S.H.I.E.L.D.’s medical system; playful power-sexual relations between her and her lover, Lance Hunter; soft critiques of the male superhero persona (e.g., Tony Stark is depicted reading a pamphlet on sexually transmitted infections while sitting in a clinic waiting room); and commentary on sexual harassment and violence through its exploration of its main villain, Phantom Rider. Mockingbird is exactly what the T-shirt advertises; an openly feminist comic set within the Marvel universe. While the politics of the comic are not subtle, and were very much part of the branding of All-New, All-Different Marvel (ANADM) in 2016, Bobby Morse’s “feminist agenda” does not necessarily translate into the company itself having such an agenda.5 Nevertheless, these politics became one flashpoint for conflicts over the future of comics as a whole, and specifically over who gets to be represented within the comics community as characters, For example, see the treatment of Anita Sarkeesian during Gamergate. In producing feminist criticism of video games, Sarkeesian’s YouTube videos “feature no calls for video games to be censored or banned. They also offer no criticisms harsher than what you might read from other pop-culture critics like Charlie Booker or Mark Kermode on some very obviously retrograde depictions of women in some video games”; nevertheless, “For this intolerable crime, Sarkeesian has endured years of jaw-droppingly dark and disturbing personal abuse” (Nagle 19–20).

3

Despite, or perhaps because of, the controversy, the image was used as the cover of the second trade for the series, Mockingbird Volume 2: My Feminist Agenda.

4

The ANADM campaign promoted a more diverse Marvel in terms of gender and racial representation, the implications of which we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 3; however, such titles by no means represented the totality of what was available to fans: Moon Knight, Daredevil, Old Man Logan, Doctor Strange, and Spider-Man/Deadpool were other titles singled out in a “best of” list for 2016 (Dave), none of which employed a feminist framework. In other words, neither Mockingbird’s overt politics nor the ANADM campaign as a whole signaled an actual wholesale transformation of the Marvel brand. 5

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

5

fans, and creators. Cain claimed that she received significant harassment on her Twitter platform, but also stated that her decision to leave was primarily because her Twitter had become a site for the culture wars to be fought, with or without her input: Comments were coming in, fast and furious, every second. I’d never seen anything like it. I saw a few of them—a lot of support, a lot of people yelling at one another—a lot of people mad at me for being too quick on the block button or too critical of comic book readers or being too feminist. A lot of them just seemed mad at women in general … it was no longer my Twitter account. It had been hijacked. (Cain, “140 Characters”) Cain’s experience with the reception of Mockingbird provides just one instance of the issues that overtly political texts and creators currently face: the success or failure of a creative text in the marketplace becomes a means for a variety of actors to keep score in a war between opposing sides over the future direction of popular culture as whole.6 But Mockingbird also demonstrates the complexity of how a “win” gets measured in the present market context. Samples from comments on just one article—Comics Beat’s October 19th coverage of the title’s cancellation—give a sense of how the comic’s demise was viewed. One commenter observed, “I’m gonna buy the trade, since I never got to see the individual books. Would have been nice if they gave people like me a chance to get on board” (“Sean” on Lu). Another reader noted, “Slow build on the comic’s readership—a lot of people only discovered it on issue #6 or #7. Canceling it with #8 is moronic. They should have waited for the trade to come out at least. It was getting growing readership” (“Nathaneal” on Lu), while “Northern Boy” crowed, “ULTIMATE IRONY: Mockingbird, nominated for a 2016 Eisner for Best New Series. Smooth move, Marvel. Smooth move” (on Lu). These comments remind us that the current way of measuring sales does not consider the myriad ways in which audiences consume comics. Marvel measures its sale numbers by single-issue sales through Diamond Comic Distributors to comic book stores, a metric by which Mockingbird was measured a failure. These laments about Marvel’s decision to cancel Mockingbird reflect a belief that the company is failing non-traditional audiences who might consume differently; for example, newer and younger readers are more likely to read digital copies or trade paperbacks.7 As well, declarations such as “I’m gonna buy the trade” In 2019, Cain faced criticism from those aligned with progressive politics for her Image series, Man-Eaters. Taken to task for a storyline that “defines women by their biological functions” (Gramuglia), Cain ended up leaving Twitter again after she included criticism from a reader on a protest sign depicted within the comic itself.

6

7 For example, both Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur and The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl have relatively low single-issue numbers, but are very popular in trades. Moon Girl in particular has benefited from an agreement with Scholastic Publishing, which sells the trades through schools.

6

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

performatively assert a politics of consumption: here, purchasing even a cancelled comic is configured as a form of social pressure to chastise Marvel for its failure to support diversity, and to encourage greater support for similar work in the future. For others, the fact that traditional floppy comic sales have been diminishing speaks to what they see as an essential truth that has been forgotten in an age of art geared toward social justice ends: namely, that overt politics and quality are incompatible. Numerous commentators on Lu’s article argued that Mockingbird was cancelled because its politics had a negative effect on the writing itself, and that sales therefore accurately reflect the book’s quality. “Sixaxis” observes, “it did seem to have far too much of an agenda and the writing was bad a fair few times. It was very in your face about the feminist nature of the book, which I really didn’t appreciate. I would’ve had no issues if it wasn’t so obviously blatant,” and “J.” likewise opined, Mockingbird was objectively bad. If you’re going to try to drive an agenda or preach through your media, then don’t be so godawful *on the nose about it* all the time. The only people really interested in reading stuff like that is people looking for material to reinforce their own particular world views … My advice to Chelsea Cain wouldn’t be to stop writing about what she likes, but instead to next time try to figure out how to get her point across through literary vehicles like allegory and symbolism. (on Lu) For these readers, the text’s announcement of its politics, as encapsulated in Jones and Rosenberg’s depiction of Mockingbird’s T-shirt, in and of itself equals “objectively” bad writing. These critics argue that good political writing is subtle, sub-textual, and/or “symbolic,” and—perhaps not inconsequentially—allows audience members to avoid being confronted by political stances or issues they do not themselves hold. While comics have always been political, this criticism that overt politics makes for bad art allows critics of such texts to avoid getting into debates about the substance of a text, such as its representation of Bobbie Morse’s bodily and sexual autonomy. Instead they focus their argument on aesthetics: it’s not the specific politics they object to, they say, but instead the negative effect than any overt politics has on art. For them, rejecting political texts or influencing others to not purchase said text is a “win” for comics as an art form, because the rejection fights back against the damaging effects of social justice politics on the presumably purer sphere of story-telling, which should rightly be about characterization, narrative, and the superhero tradition. However, the second provocation that led to the emergence of Comicsgate demonstrates the problem with this argument: specifically, that Comicsgate participants’ framing of texts as “political” or “non-political” is, in itself, a political act. While these commenters are correct that Mockingbird was

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

7

explicit in its politics (though not, we argue, in their assumption that these politics led to objectively bad writing, or resulted in a text without nuance and complexity), it is also true that including, say, Black protagonists, or representations of women in tech, or depictions of women who do not conform to normative standards of beauty, or characters who are not heterosexual, or any other of the many examples of what has come to be labeled as “diversity” is perceived as an “in your face” provocation that must be challenged.8 On July 28, 2017, Heather Antos, an editor at Marvel Comics, tweeted a picture of herself and other women working at Marvel enjoying milkshakes; it was captioned, “It’s the Marvel milkshake crew! #FabulousFlo” (Antos, July 28). The women were celebrating the life and achievements of Flo Steinberg, Stan Lee’s assistant, who had recently passed away. Steinberg was a key player in the early days of Marvel; she “answered fan mail (hundreds of pieces arrived every day), called freelancers, and shipped pages to the printer” (Howe 46) and gained many fans herself through her role as part of the Marvel Bull-Pen (56). Certainly, this tweet had a political dimension: in highlighting the diversity of the women who work at Marvel and honoring the legacy of the one named woman who was most associated with Marvel’s earlier history, the tweet signaled that the company was no longer a boy’s club. The happy, smiling faces of the group celebrate the company’s progress, and, by hash-tagging Flo’s name, the tweet also performs the feminist work of reconstructing history: Stan Lee’s name is instantly recognized in today’s pop cultural world, but Flo Steinberg, this tweet subtly reminds us, also deserves acknowledgment. But the politics implied by this tweet are, we argue, relatively neutral; it conveys an ideology that has been embraced in Western culture from at least the 1970s on: that women have a role to play in public life, and that it is a social good to break down sexist barriers and arbitrary notions of male dominance that have prevented women from entering certain fields (in this case, the editing and creating of comic books). Nevertheless, Antos found her Twitter feed overtaken by culture warriors from the left and the right as it, like Cain’s, became a site in which the future of popular culture was fought out. In response to her tweet, “Hal Jordan” complained about Antos’s influence on Marvel comics, specifically “her pushing feminism into her comics when all we need is a story not a political movement,” while “DarkJester” expressed, “No life experience, the creepiest collection of stereotypical SJWs anyone could possibly imagine.” Both tweets express a central premise of the various “-gates” within fandom: that any increase in diversity, both within texts and behind the scenes, is artificially achieved through social justice activism and corporate agendas, rather than through For a brief example of the above, YouTube channel “Comics MATTER w/Ya Boi Zack” features many videos critiquing Marvel comics as “SJW” propaganda, including several calling the much-beloved Unbeatable Squirrel Girl a “fake comic” with a “creepy agenda” largely because the protagonist is not depicted according to conventional standards of female beauty.

8

8

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

an “organic” shift. Antos’s follow-up tweet fought back against these attacks—“How dare I post a picture of my friends on the internet without expecting to be bullied, insulted, harrassed [sic], and targeted” (July 29)— and the majority of responses were supportive. For example, “Darth Rage” responded with “Who did it and I will assemble a loyal geek army to strike them down!” and “Kevin or Robo Kevin” asked, “W.W.G.P.D. What would Gwen Poole do if her friends were insulted?” These tweets engage in the work of both supporting Antos and emphasizing the tweeters’ fan identities, thereby configuring true fandom as an inclusive space in which Antos and her fellow milkshake crew belong. Others used Antos’s tweet about harassment to signal their political and social support in ways that transcend comics fandom: for example, “Nerly Señor Citzen” piped up with “Out of so many reasons to actually hate people and they choose THIS? Almost makes me start buying Marvel comics:).” In this instance, there is no evidence that this person is a comics fan specifically concerned about battles between fans and editors, only that Antos’s plight has resonated with them both on a personal level and as part of a larger battle. Their recognition of the injustice of her situation makes them willing to participate in a skirmish in which they have no personal stake, because they believe it is an important front in the culture wars. This willingness of those outside fandom to enter the fray—on both sides— makes it difficult to determine just who is involved in such controversies, or to make any assumptions about how “fandom” feels about a given conflict. Understanding the demographics of online fan communities has long been complicated by many factors: anonymity, ingroup vs. outgroup politics, and factionalism even within the ingroups. However, the emergence of social media as a powerful force in society as a whole has led to some surprising players in what might have once been small, internal conflicts. In the widely reported on study, “Weaponizing the Haters: The Last Jedi and the Strategic Politicization of Pop Culture through Social Media Manipulation,” Morten Bay claimed evidence of organized political influence measures disguised as fan arguments in the debate surrounding the film. While Bay’s claims were largely overstated by the popular press and seen as inflammatory by fan critics of The Last Jedi who rightly resented being elided with Russian operatives, Bay’s study addresses what Nagle had already demonstrated in Kill All Normies: that fan conflicts are increasingly spaces not just for expressing one’s strong opinions and analyses of texts, but also for signaling one’s position in relation to current political conflicts. Trolling, sock-puppets, and brigading9 also add to the difficulty of determining who is engaging in fan debates, and in what numbers. When popular culture debates become a tool for those wishing to inflame polarized and polarizing

Organized responses for the purposes of rallying support for a particular cause or against a particular individual.

9

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

9

discussion, analysis about what fans want or how fans feel about a given text becomes fiendishly difficult. Our analysis, therefore, will focus less on making any claims about Marvel comics fandom at the present time, and more on how the Comicsgate discourse about what fans want, and how fans feel, circulates within and outside fan spaces.

The Gabriel Debate and Online Outrage But what led to Marvel Comics, specifically, being at the center of Comicsgate? Both sides of the controversy have tended to portray Marvel as the main proponent of social justice comics, in contrast to their primary rivals at DC Comics. For example, in his negative response to the milkshake tweet, “Hal Jordan” proclaims, “Can we just get off of feminism and social justice and actually print stories. God DC looks better and better.” This tweet constructs DC as a safer space for disenfranchised fans fleeing SJW-style politics. DC has long had a reputation as being the more conservative of the two major comic book publishers;10 however, DC comics such as the newer take on Barbara Gordon in Batgirl of Burnside (2011) deliberately appeal to diverse audiences and a younger generation, and 2016’s Harley Quinn and Her Gang of Harleys directly mocked President Trump. As well, in their 2014 article for the Wall Street Journal Chuck Dixon and Paul Rivoche claimed that both Marvel and DC had succumbed to “political correctness, moral ambiguity, and leftist ideology.” The false dichotomy that has led to Marvel Comics being at the center of the Comicsgate controversy can be attributed to several factors that we will explore throughout this book: the company’s long history of promoting their stories as commentary on realworld politics; the promotion of diversity as a key marketing tactic for the company under the editorship of Axel Alonso (January 2011–November 2017); and a very specific incident in 2017 that focused attention on the role that diversity had been playing in Marvel comics for the previous few years, and which brought the issue to a larger audience. What we will refer to throughout this book as “the Gabriel controversy” occurred when Marvel’s VP of Sales, David Gabriel, commented at the March 2017 Retailers’ Summit in New York that increased diversity was hurting Marvel’s sales. Commentary on his claims reached far outside comics, with much attention focused on the role of gender and race in comics and on

In Slugfest: Inside the Epic Fifty-Year Battle between Marvel and DC (2017), Reed Tucker traces DC’s more conservative reputation to its earliest years, in which DC’s corporate-style culture “helped establish DC … as the class of the field, far different from the schlocky publishers … that had once populated the industry” (8). From the 1960s on, DC and Marvel have been defined, not always accurately, in oppositional terms: “Marvel is the eternal hipster, while DC remains the classy, conservative uncle, forever on a quest to make itself more youthful and relevant” (244).

10

10

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

whether or not, as the popular anti-diversity refrain of “get woke, go broke” puts it, highlighting social justice and diversity in popular culture lead to a loss in audience and sales.11 Jesse Schedeen argues on his IGN article, “Diversity Isn’t the Real Problem for Marvel Comics,” “Marvel’s current books aren’t struggling because of the emphasis on diversity. They’re struggling because of Marvel’s questionable, often short-sighted publishing strategies. Diversity is simply a convenient scapegoat masking a much larger problem.” However, some commenters on his article argue back, suggesting that Gabriel’s claims were in fact a welcome validation of their own feelings, and that they see Marvel’s falling sales as evidence of the righteousness of their cause: “Sorry sexual preference or ethic [sic] background doesn’t make people interesting. It’s good story telling and character building that wins” (on Schedeen, “Diversity”). On The Mary Sue article of April 1, 2017, “grimbrimm” questions, sarcastically, “I mean really, who could have foreseen that introducing a bunch of new superheroes geared towards an audience that hasn’t yet shown much interest in classic superhero comics wouldn’t pay off financially” (on Jasper), while BBurr on the AV Club article of the same date asserts, “The lesson, of course, is that the noisy internet wags who push for ‘diversity,’ political correctness and social justice in hobbies are not actually interested in those hobbies—they are only interested in making those hobbies conform to their political agenda” (on Hughes). Many of the fans who were validated by Gabriel’s comments assert similar assumptions about Marvel’s “core audience,” who one commenter defined as “people over 30 and most of them are men” adding that “SJW don’t spend money all they do is bitch” (on Schedeen “Diversity”). “Smokinclone” complains, They’re [Marvel] only alienating their largest demographic. Those white straight males you mentioned make up the largest part of their market share. That’s not a guess, that’s reality. I guess you think it’s something wrong with them because they don’t want to fantasize about being a arab [sic] lesbian fighting demons and prejudice to fit into the world. Or they don’t like watching Iceman play grab ass with every gay dude he comes across while all his friends tell him to hook up with em. (on Elderkin, “Marvel VP”) The tone and language here are very clear—superheroes who are “gay dudes” or “arab lesbians” are not ones that “white straight males” can While the idea did not originate with him, the phrase “get woke, go broke” is attributed to an interview published on Milo Yiannopolis’s blog, Dangerous, with sci-fi author John Ringo, who used the phrase to criticize ConCarolinas and its handling of political controversies about invited speakers. The idea that diversifying popular culture texts such as comics, video games, and action films will result in alienating the presumed primary audience of White men has been around for some time, but it achieved widespread support with Gamergate and with the organized reaction on YouTube against the 2016, all-female, Ghostbusters reboot.

11

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

11

“fantasize about”—or, perhaps more accurately, that they can fantasize about being. But the fear expressed by these fans about political pressure being exerted by groups who are not the “traditional” audience (although there is no evidence that those who want greater diversity in comics are not fans themselves) is also one that can be linked to increased corporate control of creative industries. Comics are more than simply stories: they are lucrative products, run by businesses that are very much aware of changing demographics in society. When angry fans complain, as one did on the io9 article, that non-comic book fans “were symbolically purchasing not because they actually cared about comics but because they supported the initiative” and that “at some point that sort of performative consumerism ends” (“Carl” on Elderkin), they are expressing fear of newer, and possibly more desirable, audiences. On the same article, Joshua Sibley remarks that “Cap, Thor, Iron Man, etc. survived in a society outright hostile to comics since the fucking 40’s. Their exploits have been around so long they’re practically mythology. I’m so tired of these Tumblr kids coming in like a sociology professor and lecturing us that the medium isn’t being done right because of our biases.” All of these commenters agree on the same things: “hipsters/millennials and Tumblr kids” are ruining comics through a combination of insufficient buying power, agenda-driven taste, and a lack of true investment and follow-through that sets them apart from the dedicated, longer-term fan; their purchases are only for appearance, rather than a sign of true fan devotion and “investment.” These complaints enunciate not just ageist assumptions about millennials, Gen Y, and Gen Z, but also fears that the buying power of traditional readers is no longer sufficient to influence creative industries to cater solely to their tastes and to represent their interests as they once did. While the media coverage of Gabriel’s comments provided a space for the public to voice their opinions on diversity in popular culture, perhaps no site worked to feed the controversy as much as YouTube. Gamergate played a substantial role in transforming many channels that had been devoted to “skepticism” (such as critiquing religion and debunking pseudoscience) to framing feminists and “social justice warriors” as the new threats to rationality and “centrism.”12 Similarly, in the wake of the Gabriel controversy, numerous YouTube channels emerged to cover what they constructed as the undue influence of “SJW” politics on comics, and to stoke audience anger against a variety of targets, mainly women in comics, but also male creators who were viewed as pushing a social justice agenda, such as Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Waid. Richard Meyer, in particular, produced the channel “Diversity + Comics” (replaced with “Comics Matter

For example, channels like “Sargon of Akkad,” “thunderf00t,” and “Armoured Skeptic” all focused on atheism, free speech, and rational thought but, in the wake of Gamergate, shifted almost entirely to anti-SJW content.

12

12

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

w/Ya Boi Zack”), which at its height offered numerous videos a day with the sole purpose of expressing outrage against diversity in comics; some sample titles include “The SJW Stranglehold on the Comic Book Industry Is Finally OVER,” “UNSTOPPABLE WASP #8- The Monstrous & Empty Egotism Of SJWs Is Truly Appalling,” and “Is SJW Marvel Destroying the Direct Market & Comic Book Shops ON PURPOSE?” The click-bait titles often belie a dearth of content, as these videos repeatedly relay the same perceived grievances. Nevertheless, his format of extremely low-budget videos featuring unscripted, often rambling monologues has been highly successful; he has garnered over 100,000 subscribers and receives view counts often exceeding 20,000. The same formula and alt-right perspective are used by many other channels, some of which, such as “Just Some Guy” and “ComicArtistPro Secrets” (run by comic artist Ethan Van Scriver), also enjoy high subscriber counts. Operating as they do on an algorithm that seeks to maximize viewers by recommending similar videos to audiences, these channels are rewarded for producing numerous videos on the same or similar topics, regardless of the quality of their production or their content. But the view counts also give the illusion of a large social movement organizing against the diversification of superhero comics, with the actual demographics very difficult to verify. The purveyors and fans of this movement saw Gabriel’s reiteration of two comic book store owners’ comments as an opportunity to push back against diversification: if Marvel’s VP of Sales was willing to say that diversity was hurting Marvel’s bottom line, then this provided an avenue for those who opposed diversity to organize a soft boycott. Anti-diversity comments and videos lean heavily on the “get woke, go broke” principle because the people who make them want to pressure Marvel to abandon diversity as a goal, and to “save” comics from those who they construct as outsiders to comics fandom. But there is no evidence that those consuming these videos or leaving these angry comments are themselves comics fans. As with Gamergate, which drew in allies from outside gamer culture, so too did Comicsgate appeal to an audience of reactionaries who likely were never the sole, or even primary intended audience of the comics they vowed to boycott. Instead, their outrage served to bolster the small economies of producers on YouTube who could count on them to view each new “cringe” video critiquing the failures of SJW comics.

Escaping the Cycle of Voting with Our Dollars and Evaluating According to Our Politics The Gabriel controversy effectively made Marvel’s financial successes and failures during the Comicsgate period primarily about diversity, allowing the company to sidestep many other issues at play that might have been affecting

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

13

their bottom line, such as: weariness with continual events that disrupt story-telling across numerous titles; the growing expense of single issues; the cancellation of series before they have a chance to find an audience; poor advertising for new titles; and weaknesses in the creative bench brought about by greater autonomy for creators offered by competing companies, such as Image.13 Gabriel’s comments could be dismissed as those of a single corporate executive, but they could also cynically be read as the company attempting to either (a) drum up support politically for its “diverse” titles or (b) shift blame to audiences should Marvel pivot away from Alonso’s stated aim to diversify its lines. Marvel’s handling and mishandling of diversity within the comics and their marketing further contribute to the difficulty of evaluating the success and failure of overt politics in storylines. The ongoing polarization of fans and audiences pushes critique either firmly into the “Comicsgate” camp, a space which we have no desire to occupy, or into encouraging politicized consumption, which we also wish to avoid. Our own politics are decidedly leftist and pro-diversity, but we reject the idea that good art has to replicate or represent our own politics, and we are highly suspicious of social justice that is reduced to a corporate brand. Which brings us to the question: is it possible, or even desirable, to evaluate the comics that are at the center of these debates without acknowledging their role as proxies in endless culture wars? As this introduction should indicate—no. The context of these debates is essential to understanding the creation, content, and reception of the comics we will examine: specifically, Ultimate Comics Spider-Man, Ms. Marvel, The Mighty Thor, Captain America: Sam Wilson, and Secret Empire. However, we want to move away from simplistic arguments that boil down to “thumbs down on racism or sexism” or “politics make for bad storytelling” to instead place these comics within what we see as a more complex context: that of evaluating popular culture texts that are both a fairly cynical form of corporate art and sincere expressions of creative/political thought on the part of individual comics storytellers. We hope to identify those moments in these texts when politics makes them their best, and when politics makes them their worst. We have chosen these comics not because they are the most representative of diversity in comics—important texts such as Gabby Rivera and Joe Quinones’s America (2017) and diverse characters such as Amadeus Cho (the Hulk/Brawn) and Riri Williams (Ironheart) will not be examined here—but because they are the ones we believe have been positioned by Marvel Comics and its corporate branding as both overtly political and representatives of the future of the brand. Comics like Mockingbird and America, for example, break barriers both through their creative benches

13 Graeme McMillan’s article for The Hollywood Reporter. entitled “2017: The Year Almost Everything Went Wrong for Marvel Comics,” provides a painful overview of the many missteps and PR disasters that shook the company in that single year.

14

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

and through their political subjects, but both deal with characters on the margins of the Marvel universe. By contrast, the comics and characters we have chosen to discuss are ones that have brought debates about diversity into the mainstream and have succeeded in becoming central to Marvel Comics projects going forward. That the majority of them are written and illustrated by White men, many of whom are stars within the comics industry, is very much part of our discussion. Marvel Comics might be viewed by some Comicsgate participants as particularly given to “political shilling” and “forc[ed] political correctness” (Del Arroz), but it is also in many ways still a fairly conservative company, and its forays into diversifying its superhero stable must be understood within that context. Before outlining our chapters, we want to acknowledge a significant absence in our text: as any comics reader and scholar knows, comics are both a visual and a literary medium, and yet there are no images included in this book. Because we could not secure image permissions from Marvel, due to current company policy about third-party works where Marvel is the sole subject (as is the case here), our analysis leans toward the verbal text of the comics, which we can quote. Where we can, we do describe panels and analyze images, but such description can never have the same authority as actual reprints of the images themselves, so we have chosen to limit it. Our text does not therefore provide as much of the “formal analysis” and attention to “line, color, and image” (“Surveying the World” 143) as comics audiences rightfully expect, but we hope we provide the best analysis possible within these limitations. Our first chapter traces the relationship between real-world politics and the Marvel Comics universe, from the beginning of the Marvel brand to the new millennium, with a focus on how Marvel employs politics as a tool for fan engagement. Using theories of corporate authorship, we argue that Marvel has often referenced contemporary politics in its storylines in ways that deliberately align Marvel with its intended fanbase. Marvel Comics has been an inconsistently progressive voice from the late 1960s on, producing storylines, for example, that engaged directly with the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and with the Nixon administration in the 1970s. Extra-textual elements, such as Stan’s Soapbox and editorialization in the letter columns, worked to link the company with the liberal agendas expressed in the stories. As part of this liberal positioning, Marvel has always developed diverse characters and political storylines, but we argue that it did so primarily in ways that still preserved its comics as “safe” reading for general audiences. This desire to produce a corporate art that fits the company’s liberal, and sometimes progressive, branding, but preserves the widest possible audience, has led to a continual balancing act in which stories negotiate the tensions that can exist between editors, creators, and audiences in relation to political issues. Our second chapter moves forward to the early 2010s and to the beginnings of Marvel’s current wave of deliberate political marketing.

INTRODUCTION: MOCKINGBIRD AND MILKSHAKES

15

The new millennium witnessed a concerted push to diversify comics so as to expand comics’ readership and reflect changing demographics. This chapter provides close analysis of the first series of two new diversity characters: Brian Michael Bendis and Sara Pichelli’s African- and LatinxAmerican Miles Morales in Ultimate Comics Spider-Man (2011–2013), and G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona’s Muslim Pakistani-American Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel (2014–2015). In the wake of the Gabriel controversy, these characters were often held up by opponents of diversity as models of “diversity done right.” This chapter explores what allowed these two to become beloved additions to the panoply of superheroes, despite being positioned and marketed as diversity characters. We argue that both Miles and Kamala found favor with many fans because they are depicted as simultaneously universal and culturally specific. This duality allowed their comics to bring in new readers without challenging the overall Whiteness of the superhero stable and its representation of normative power relations. If Miles Morales and Kamala Khan represent what opponents of “forced diversity” in Marvel Comics find acceptable, then Jane Foster/Thor and Sam Wilson/Captain America embody what many fans described as most objectionable: diversity characters who have taken up the mantles seemingly at the expense of beloved characters. In Chapter 3, we argue that these gender- or race-bending legacy characters differ from Miles Morales and Kamala Khan in that in each case the original character is stripped of power in order for the mantle to be passed, with the replacement then read, by disappointed or openly hostile fans, as a wholesale challenging of political/ social representation in the Marvel universe. We focus our discussion of mantle passing and the challenges it poses to racial and gender norms through close analysis of Nick Spencer and Daniel Acuña’s Captain America: Sam Wilson (2015–2017) and Jason Aaron and Russell Dauterman’s The Mighty Thor (2015–2018), but we also situate that discussion within the wholescale mantle passing that happened from 2014 to 2016 in the ANADM campaign. While we believe that gender- and race-bending existing characters can, at its worst, represent pandering, temporary diversity, we argue that Sam Wilson as Captain America and Jane Foster as Thor instead reveal the potential of such creative revisionings, specifically in terms of reassessing the historical legacy of characters and mantles in Marvel’s long history. Chapter 4 addresses an event that united progressives and traditionalists in their rejection of it: Nick Spencer’s 2017 Secret Empire. The decision to retcon Steve Rogers/Captain America into an agent of Hydra angered both those who saw it as an insult to the character’s Jewish creators, and those who were offended by what they perceived as the event’s use of fascism to reference current American politics under Donald Trump. While we acknowledge the problematic marketing of the event, we argue in defense of Secret Empire as both a story and a creative intervention into contemporary politics. We assert that, despite what its many critics claim, the event largely

16

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

succeeds in being an uncomfortable and challenging examination of hero worship and nostalgia in an age of rising fascism—one that critiques not just the current political climate but also the superhero genre itself. Nevertheless, the event was also marred by its marketing and by Marvel’s frantic efforts to manage audience and critical reactions, particularly in terms of disavowing the politics so central to the story itself. The tensions between the storyline and marketing demonstrate the difficulties facing creators and audiences who wish to employ corporately owned cultural icons to make sense of, and challenge, contemporary politics. Our conclusion addresses the vestiges of Axel Alonso’s efforts at diversity in an examination of Marvel Legacy (2017) and Fresh Start (2018). These launches, coming as they did on the heels of the controversial ANADM campaign, were widely viewed as Marvel capitulating to anti-diversity backlash and rebranding itself away from the political fall-out of Comicsgate. In our assessment of these re-launches, we instead see a continuation of Marvel’s long-term strategy of negotiating between its corporate branding of itself as progressive and its own conservative, corporate interests. Nevertheless, we also argue that the ideals espoused in the marketing of ANADM do indeed live on within these new launches, particularly in terms of increased diversity on the creative bench. At the heart of this manuscript is a question: can Marvel’s strategy of safe, liberal politics succeed in the current political climate? We argue that Marvel needs to continue to reflect back on the emergence of a “Marvel philosophy” in the late 1960s and on the risks taken by its younger creators during that time period, to recognize that stories that either pander to a desired fanbase, or attempt to safely navigate the political status-quo, are not the ones that will serve during a time of immense political divides. Rather, Marvel Comics needs to recognize that the ideology of its corporate art, which is central to what has distinguished Marvel over the years and given its universe its (mostly) coherent tone and style, is currently at odds with its desire to please everyone in a polarized political climate.

1 From Stan’s Soapbox to Twitter: Politics and Story-Telling in the Marvel Universe

If anything defines “Comicsgate” as a movement, it is the slogan “get woke, go broke,” the belief that Marvel’s attempt to diversify its superhero stories is a corporate-driven mandate that is bound to fail. Proponents of this philosophy give varying reasons for why this push for diversity will ultimately destroy Marvel comics. Some argue that such an approach alienates the existing fanbase, assumed—and often stated—to be White men. Others believe that the desire to diversify will lead Marvel to equity-based hiring that prioritizes appointing people from under-represented groups, rather than—implied, but also sometimes stated to be—more qualified White men. Many fans protest that they are absolutely in favor of diversity, just not “forced diversity,” and point to successful characters ranging from Luke Cage to Kamala Khan to point out that Marvel has done diversity well in the past, but that the wholesale transformation under Axel Alonso and represented by the All-New, All-Different Marvel campaign fails primarily because it is a shallow and pandering corporate-driven exercise. In all of these arguments, however, there is a consistent point of connection: that politics in story-telling, both on the page and behind the scenes, is intimately tied to the economics of selling comics. As audiences, we are therefore encouraged by both sides to “vote” with our dollars, consuming and/or boycotting Marvel Comics in ways that match our values. David F. Walker’s list of “10 Ways to Really Support Diversity in Comics,” for example, not only emphasizes the importance of fans’ financial support (with five of the ten points focused on purchasing), but also states that “not pre-ordering comics from a direct market retailer is the same as NOT supporting a book. That’s the system.”

18

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

At the same time, independent comics creators often use political rhetoric to encourage fans to support their Kickstarter and Indiegogo campaigns as a way of producing comics that “the system” will not.1 In this chapter, we challenge the explicitly political marketing of mass culture texts such as Marvel Comics, without downplaying the need for greater diversity both within and behind the scenes of superhero comics stories. Carolyn Cocca argues that within popular culture, Marginalized groups have been forced to “cross-identify” with those different from them while dominant groups have not. That is, because white males have been over-represented, women and people of color have had to identify with white, male protagonists. But white males have not had to identify with the small number of women and people of color protagonists. This is not only unfair, but can curtail imagination. (3) Like Cocca, we believe that stories that draw upon a wide range of human experiences and identities are necessary not only for the good political work they do in terms of challenging the “representations of stereotypes that exert power” (5), but also for creating richer, more complex, and more relevant works of art that expand the imaginations of their audience. We are nevertheless wary of “social justice” and “diversity” as marketing tools for corporations, particularly one with as spotted a history as Marvel’s in terms of its treatment of its creators. In part, this wariness is simply a rejection of woke-branding as a whole, whether it originates from Dove, Gillette, or Pepsi: these campaigns arguably exacerbate culture wars all in the service of selling their products and, sometimes, as in the case of “wokewashing,” “cynically [cash] in on people’s idealism and [use] progressiveorientated marketing campaigns to deflect questions about their own ethical records” (Jones). As we will discuss, there is good reason to see Marvel as engaging in both. But we are also concerned that diversity as a marketing ploy can result in shallow characterization and pandering story-telling that fail in the important work of increased representation in art. Bad representation is arguably as damaging as no representation at all, in that stereotypes not only shape the dominant culture’s attitudes toward the represented people, but can also shape the attitudes of people desperate to see themselves in the texts they consume. Even when those representations are positive, their scarcity means that they bear an undue weight of signification. Adilifu Nama underlines this point when he uses a quote from Dwayne McDuffie as his epigraph to the Introduction of Super Black: American Popular Culture and

Successful examples on either side of the political spectrum include Comicsgate founder Richard Meyer’s Indiegogo campaign for his comic Jawbreakers, which raised over $500,000 and (on the other side) the three separate volumes of Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection, each of which raised around $75,000.

1

FROM STAN’S SOAPBOX TO TWITTER

19

Black Superheroes: “My problem … and I’m speaking as a writer now … with writing a black character in either the Marvel or DC universe is that he is not a man. He is a symbol” (cited in Nama 1). The path to authentic and adequate representation in mainstream comics is, therefore, a long one fraught with pitfalls for even the most careful and aware writer. Despite these difficulties, we give no credence to arguments that diversity and greater representation threaten superhero story-telling in and of themselves. Instead, we argue that Marvel’s push for diversity under Axel Alonso cannot be read as separate from Marvel’s corporate agenda and economic interests. We place ANADM firmly within the company’s long history of presenting itself as a liberal voice, in varying iterations, so as to help us better understand how its overt political story-telling serves a variety of sometimes conflicting agendas.2 By tracing the relationship between “liberalism” and the Marvel Comics universe from the beginning of the company to the new millennium, we assert that Marvel’s many political storylines result from a continual negotiation of social pressure from multiple directions: corporate, editorial, creative, and audience. Furthermore, we suggest that Marvel’s corporate creation of an ongoing, historically shaped continuity that they repeatedly claim mirrors “the world outside our windows” encourages both creators and audiences to use the characters and storylines as surrogates and stand-ins for real-world political examination. The multiple nature of both comics authorship and comics audiences means that Marvel’s diverse characters and political storylines are not singular, but have created, encouraged, and fomented political debate, often in ways that Marvel, as a corporate author, might not have intended or endorsed.

Corporate Art and Corporate Authorship Before we discuss the role Marvel superhero comics play in political discourse, we must first acknowledge the limitations and impediments to sincere political debate within superhero comics, especially as they are produced by the Big Two (Marvel and DC). In “Buster Brown at the Barricades: Foment in the Funnies & Comics as Counter-Culture,” Alan Moore argues that because early cartoons and comics were “unrestricted by prevailing notions of acceptability,” they had the potential to give “voice to popular dissent” or to become, “in the right hands, a supremely powerful We use “overt” to describe those storylines that consciously and deliberately engage in topics such as geo-political conflict, race/gender/class debates, and “ripped from the headlines” commentary on current political events. We believe that all stories are inherently political insofar as they are framed within or respond to dominant ideological frameworks for understanding ourselves and our world, but we are specifically interested here in storylines that are meant and understood to be political in focus.

2

20

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

instrument for social change.” In other words, because of its separation from high art, the comics medium provides a space to represent the desires of the powerless and the disadvantaged in society, to puncture the respectability of the wealthy, and to revel in power fantasies that redress injustice against the oppressed. Moore highlights the continuity between blasphemous cartoons from the French Revolution, to the underground comix scene of the 1960s, whose “main targets for subversion … were the prissy and sedate traditions of the medium itself,”3 to the current moment, in which “the sole restrictions on what comics can or cannot be are those of the creator’s own imagination.” Like other popular media and genres that reach a wide audience and contain anti-authoritarian content—rap music, punk subcultures, pornography, drug culture, etc.—comics have faced external, legal pressures that sought to weaken their power to disrupt the cultural status quo; the Comics Code of 1954 (like similar laws worldwide) offers an example of indirect governmental censorship and control of a subversive medium, aimed as it was at ensuring that comics adhered to strict guidelines in terms of representing mainstream political ideologies and morality.4 But Moore also alludes to the “taming influence of the remunerative market” in that same essay, tracing how cartoons became “socially sanctified,” which is a common trajectory for many forms of popular culture when they are absorbed into corporate-owned mass production. He complains that “it was seen as more appropriate for these new U.S. totem entities to be in the possession and safekeeping of frequently questionable businessmen rather than that of the genuinely talented and decent human beings who’d originated them.” Moore’s historical narrative of the subversive power of cartoons and comics is a fairly straightforward one: creators produce meaningful symbols of populist dissent that draw upon the medium’s “gutter-generated origins,” which then gradually become sanitized by their absorption into the mainstream. In the case of Superman, for example, While the ensuing decades and expanding fortunes of America have seen Siegel and Shuster’s purloined champion recast as an establishment ideal, a figure that embodies tactical superiority and thus perhaps a sense of national impunity, the archetypal superhero at his outset was a very different proposition. In his earliest adventures, with an admirably broadminded definition of what constituted criminality, a splendidly egalitarian Man of Tomorrow would rough up strike-breakers and use This resulted in taboo-breaking narratives focused on “sex, violence, and criticism of authority figures and the establishment” (García 12).

3

Although the Comics Code was a self-regulation of the industry, it was a direct response to the fear of government regulation in the face of the moral panic provoked by Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent. The Code required the elimination of explicit horror tropes and sexuality from the genre, and required a mainstream morality in which crime was not glamourized, and policemen and other people in authority were not criticized.

4

FROM STAN’S SOAPBOX TO TWITTER

21

his super-strength to hurl unscrupulous slum landlords over the horizon. Gradually across the next few years, perhaps in keeping with the Cleveland pair’s decreasing power to control their own creation, Superman would undergo a moral and political makeover to become a bastion of authority, carefully trimmed of any prickly or non-conformist attitudes. According to Moore, the full co-option of Superman within the corporate structure of DC leads to a bastardization of his meaning as a cultural symbol for the oppressed: owned and controlled by corporate powers, Superman comes to represent those interests instead. What Moore identifies as the cause of the transformation of Superman’s character, therefore, is less explicit government censorship than it is the appropriation and incorporation of popular culture into “mass culture.” Mass culture is produced by capitalist industries for consumption by the masses, and thus inherently carries with it “the interests of the economically and ideologically dominant” (Fiske, Reading 2). Critics such as Alan Moore are correct to question whether large corporations—which pursue financial goals, often at the expense of artistic expression and innovation—can produce texts that contain subversive elements. Mass culture theorists, for example, have long highlighted the empty escapism of corporate creative products: “Entertainment offers the image of ‘something better’ to escape into, or something we want deeply that our day-to-day lives don’t provide” (Dyer 20). This escapism, however, is strictly limited, as the most pessimistic of the mass culture theorists point out, because mass culture “infect[s] everything with sameness” (Horkheimer and Adorno 53), limiting the scope of the audience’s imagination (56) and offering no alternative to the current political and economic status quo (54). The superhero genre is arguably the most mainstream genre within the comics medium and, at its worst, is characterized by banal repetition and a celebration of dominant power structures. The Big Two, for example, have continually copied each other’s creations; the popularity of Superman led to a “legion of ‘long underwear’ imitators” (Duncan et al. 18), whose characterizations and storylines tend to follow set patterns: origin stories, colorful costumes, super-powers, dual identities, and pro-social missions exemplified by “strength of will” and a “sense of duty” (197–210). While every popular genre has characteristic elements, the extent to which a text unimaginatively follows such conventions, rather than subverting or challenging them, can be attributed to mass culture industries’ desire to produce “texts that are minimally acceptable … to a huge audience” (Radway 285). Comics that closely adhere to tried and true formulas, rather than subversive or refreshingly original content, will satisfy the majority of fans of that genre, and thus remain the safest bet for a corporation dedicated to profits, rather than art. Finally, the pro-social missions of the superhero, while not explicitly serving Western geo-political power and capitalism, do not inherently subvert them either. Instead, the superhero in the hands of

22

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

these two corporate giants becomes, at least on its surface, an authoritarian figure who enacts “might makes right” on a global, even galactic, scale, fighting to preserve moderate politics, and engaged in generalized stories of good vs. evil that do not challenge the financial or political order.5 While Marvel Comics has a long history of promoting liberal politics and engaging directly and indirectly in contemporary political issues, we argue that these facets of their story-telling, rather than subverting the political and financial status quos, instead operate firmly within them. Like the studio system Jerome Christensen analyzes in America’s Corporate Art (2012), Marvel Comics produces “corporate art,” a term used to describe “a tool of corporate strategy” that is adopted “to attain competitive advantage” and implemented by executives who “successfully claim the authority to interpret the intent of the corporation and project a policy that will advance its particular interests, whether financial, social cultural, or political” (Christensen 2). Specifically, we argue that while individual creators play a crucial role in shaping comics’ characters and storylines, we must understand the Marvel Universe as one authored by “Marvel Comics,” a corporate author who is personified as a singular entity, and whose texts are linked to a specific “brand.”6 The brand that Marvel Comics has successfully created for itself is primarily aligned with liberal politics, leaning sometimes more centrist, and sometimes more progressive. And while these politics may indeed be those held by people with some power in the organization, such as Stan Lee or Axel Alonso or (in the case of the MCU) Kevin Feige, and some influence, such as individual writers and artists, they exist primarily to advance the company’s financial interests, in terms of both setting itself apart from its “distinguished competition” and courting new or under-served audiences. Its comics and its editorial columns personify the organization as a liberal entity whose interests, it would appear, are as pro-social as those of its superheroes; in so doing, Marvel Comics participates in “soul making,” a strategy meant to “invest corporations with pathos” (Christensen 9). Marvel’s marketing strategies also support this goal, “insofar as the project of marketing involves For example, Chris Gaveler’s history of the superhero highlights the “imperial underpinnings” (34) of the character type, as well as its linkage to fascism, eugenics, and vigilantism: “The superhero, despite the character’s evolution into a champion of the oppressed, partly originated from an oppressive, racist impulse in American culture, and the formula codifies an ethics of vigilante extremism that still contradicts the superhero’s purported social mission” (78).

5

We are modeling our reading of Marvel Comics on what we consider a similar industry: the Hollywood studio system. Jerome Christensen describes this system as follows: “The personification of a studio is an identification that people may recognize, but not one to which anyone must consent. A personification of the studio is, ultimately, an element of the corporation’s brand, one of the cluster of associations people make when they hear the name ‘MGM’ or ‘Disney’” (21). In other words, the personification of corporations is a strategy that distinguishes one brand from another, and encourages consumer identification with and loyalty to the corporation.

6

FROM STAN’S SOAPBOX TO TWITTER

23

the establishment of social legitimacy of a company that seeks to make customers for its products rather than simply make products it can somehow sell to a customer” (9). Marvel’s soul-making project, one dedicated to creating lifelong fans invested in the company and its products, rests on the following strategies: the representation of its universe as linked to our own, and therefore as a space in which its in-world political commentary can both mirror and influence politics in our world; the development of storylines and characters that enunciate or embody liberal values such as diversity and open-mindedness; and the employment of its editors—best exemplified by Stan Lee engaging directly with the audience through his “Soapbox” and through the letter columns—as the voice of Marvel that speaks for, and enunciates, its politics as a whole. Complicating the liberal voice of Marvel as author is the fact that its corporate authorship has often led directly to the exploitation of individual storytellers, particularly the creators of the characters and storylines that won the corporation such approval from the younger generation in the first place. Jack Kirby described his time at the company as one of “repression” and rightly complained, “I was never given credit for the writing I did … I was faced with the frustration of having to come up with new ideas and then having them taken from me” (qtd. in Howe 118). Likewise, Sean Howe relates how Marvel engaged in a variety of exploitative moves, such as reviving characters “just long enough to ensure their copyright claims” against creators (76), using one part of a creative team against another to undermine such claims (77), refusing raises and contracts “because [workers] could be so easily replaced” (93), and continually failing to reward those who were loyal to Marvel: as Bill Mantlo relates, “It was a sign of success to shit on the company, go somewhere else, and then come back, and Chris [Claremont] … and [I] … were left cleaning up the manure, without thanks, without reward” (qtd. in Howe 157). Older writers and artists who were perceived as “old-fashioned” were “put out to pasture” (277), and even Chris Claremont received “no good-bye in the letters column, no announcement in the press” (328) when he was pushed out at Marvel, despite his impressively long and highly influential run penning the X-Men universe. All of this meant that creators were often afraid to unionize (209), but were not rewarded with secure work when they opted not to do so. As a result, there are few creators who worked at Marvel and were central to the company’s success that left the company on good terms. This tendency changed a little in the first decade of the twenty-first century, when Joe Quesada began a strategy of bringing in new talent from successful independent comics and recognizable names from outside the comics industry and promoting artists and writers as a type of “commercial auteurism” (Overpeck 165). The promotion of individual talents coalesced in the 2010 Marvel Architects promotion, which the company “used to create the sense that stories set in the Marvel Universe have been parts of one overarching narrative that has been designed by a team of important

24

SUPERHERO CULTURE WARS

writers” (Overpeck 165). In this way, the “Architects”—Jason Aaron, Brian Michael Bendis, Ed Brubaker, Matt Fraction, and Jonathan Hickman— together with the editor-in-chief—first Quesada, then Alonzo—occupied the place formerly associated with Stan Lee, as “stewards of the Marvel Universe” (Overpeck 177). Significantly, Aaron and Bendis are responsible for two of Marvel’s most heavily promoted diversity changes that we will be discussing: Miles Morales as Spider-Man and Jane Foster as Thor, respectively. However, this promotion of specific storytellers is still a corporate strategy, and one not all creators feel supported by.7 For example, Iceman writer Sina Grace complained about the lack of promotion both he and his comic received from Marvel and, more explicitly, about the lack of support he received in the face of backlash. As he sums up in a Tumblr post: “We as creators are strongly encouraged to build a platform on social media and use it to promote work-for-hire projects owned by massive corporations … but when the going gets tough, these dudes get going real quick.” This complaint suggests that Marvel uses creators to build up a brand following, one often based on liberal politics, but then abandons them if those politics have real-world consequences. One might argue that Marvel’s treatment of its creators does not necessarily have a bearing on the politics of the storylines and characters themselves; however, if we understand creator control and freedom over intellectual property (IP) as central to challenging the more flattening effects of mass-market culture, we can understand how Marvel’s adoption of a consistent “house style,” one that could be reproduced by legions of replaceable writers and artists, affects its content. Subversive political content is often linked with greater creative power, as Enrique García describes of the underground comix scene of the 1960s: “Artistic and economic independence was the main motto of comix artists, and it allowed them to make exciting narratives without being exploited by corporations” (12). By contrast, as Marvel sought to protect its IP from creators, it lost many of its strongest creators and instead employed fans to replace them. As Howe observes, Many of the most provocative and vital writers and artists of the previous generations, chased away by the industry’s paternalistic and/or just plain unfair policies, were off to other pursuits … Those who remained in the field would have to make a go of it within the strictures of the system, waiving royalties and reining in their more esoteric flights of fancy. (213)

After publicizing her dispute with Marvel over the cancellation of The Vision in 2018, Chelsea Cain proclaimed, “Yeah, I’m dead to them. Trust me.” Her comment, “When people say that they don’t want anybody to look bad, they always mean they don’t want themselves to look bad,” highlights the highly conflictual nature of the creator-corporate relationship (Arrant).

7

FROM STAN’S SOAPBOX TO TWITTER

25

Furthermore, Marvel’s growth as a company led to numerous cross-licensing and business-enhancing opportunities, such as television shows, cartoons, and toys, which made taking creative risks within their increasingly lucrative superhero universe anathema to the company’s best interests: in the late 1960s, “Lee had conveyed to his writers that Marvel’s stories should have only ‘the illusion of change,’ that the characters should never evolve too much, lest their portrayals conflict with what licensees planned for other media” (101). The idea that characters only had the “illusion of change” would support continuity—for example, making Thor consistent whether the story-telling was done by Kirby, Simonson, or Aaron—but that commitment to consistency in turn downplayed the contributions of individual storytellers, making them susceptible to abuse by the corporation.