Stuyvesant Bound: An Essay on Loss Across Time 9780812208023

Stuyvesant Bound is an innovative, compelling reassessment of the last Director-General of New Netherland. Donna Merwick

172 60 1MB

English Pages 248 [243] Year 2013

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

Preface. The Outcast

I. Duty

Chapter 1. Magistracy and Confessional Politics

Chapter 2. Conflicts and Reputation

Chapter 3. Protecting by Deterrence

Chapter 4. “The General”

Part II. Belief

Chapter 5. The Struggle to Believe

Chapter 6. Managing Conventicles

Chapter 7. Ordinances: The Needle of Sin

Part III. Loss

Chapter 8. To Suffer Loss, 1664–1667

Chapter 9. Dismissal and Return

Chapter 10. Stuyvesant Tattooed

Chapter 11. A Place in Early America

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Citation preview

Stuyvesant Bound

Early American Studies Series editors: Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

S t u Y v es a n t Bou nD A n E ss a y o n L o ss A c r o ss T i m e

Donna Merwick

u n i v e r si t y of pe n n s y lva n i a pr e s s ph i l a de l ph i a

Copyright © 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 www.upenn.edu/pennpress Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merwick, Donna. Stuyvesant bound : an essay on loss across time / Donna Merwick.—1st ed. p. cm. — (Early American studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8122-4503-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Stuyvesant, Peter, 1592–1672. 2. New Netherland—History. 3. New Netherland—Historiography. 4. New York (State)— History—Colonial period, ca. 1600–1775. 5. Dutch—New York (State)—History—17th century. I. Title. II. Series: Early American Studies. F122.1.S78M47 2013 974.7'02092—dc23 2012038311

To Virginia

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

Preface: The Outcast

ix

I. Duty 1 Chapter 1. Magistracy and Confessional Politics Chapter 2. Conflicts and Reputation Chapter 3. Protecting by Deterrence Chapter 4. “The General”

3 20 33 46

II. Belief 59 Chapter 5. The Struggle to Believe Chapter 6. Managing Conventicles Chapter 7. Ordinances: The Needle of Sin

61 72 84

III. Loss 101 Chapter 8. To Suffer Loss, 1664–1667 Chapter 9. Dismissal and Return Chapter 10. Stuyvesant Tattooed Chapter 11. A Place in Early America

103 121 136 151

Notes 167 Bibliography 201 Index 213 Acknowledgments 221

This page intentionally left blank

Preface

The Outcast

A haunting representation of Peter Stuyvesant rests among the documents relating to New Netherland. Stylistically it is similar to a line drawing. Spare, sensuous, and provocative, it is like a simple piece of graffiti. It is only fortynine words. Stuyvesant is described as a captive. He is a lone figure being driven across the land with his hands bound behind his back. Nothing indicates the cause of his enforced journeying. Whatever his past in the country from which he is being driven, it is over. His future is commented on. His journey could end in one of three outcomes. He might simply be banished. Or, should his captors become impatient and see no value in him, he might be killed. But if, wherever he finishes up, he lives quietly, that would be allowed. He could remain “in his own house and on his land, like any other man.” The tethered figure would have been known to local natives, some of whom were present to hear the description (Figure 1). He has a wooden leg. Whether this had previously inspired a sense of awe in them or aroused an uneasy awareness of something specially chosen about this figure—a strange version of a man—is hard to tell. They did notice it. And often other natives took the opportunity to refer to it. For seventeen years, the defeated and humiliated outcast had been the director general of Dutch New Netherland. The storymakers preferred to call him just “Stuyvesant.” The image of rejection and loss is an accurate one. It was constructed on January 1, 1664, just eight months before an English fleet entered the harbor of New Amsterdam and forced the surrender of the city and province. A number of Englishmen had gathered at the Long Island village of Vlissingen (Flushing) in order to convince nearby natives to sell them tracts of land previously sold to the Dutch. They warned that many Englishmen were soon

x Preface

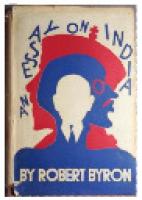

Figure 1. Indian Warriors Returning with a Captive. Copy of Iroquois (probably Seneca) pictograph, circa 1666. Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

coming from overseas in three ships. The Dutch would be made to leave. The lands would become English: best now to be on the winning side. At that point, the Englishmen personified the loss of New Netherland in the figure of Stuyvesant. “If Stuyvesant tried to do anything,” the men told the natives, “they would bind his hands on his back and send him out of the country or kill him, but if he kept quiet, it would be well and he might remain in his own house and on his land, like any other man.”1 They knew the image would evoke scorn. It would resemble the visual impersonations occasionally drawn by the natives themselves (Figure 2). The powerlessness of the man is easily read. His body wears three markers of defeat and loss. Each is within the possible experience of mid-seventeenthcentury North Americans. He is chained or bound with ropes. He is forced to be on the move. He is subjected to captors who will finalize his fate but are presently enjoying his suffering and in no hurry to do so.

The Outcast xi

Figure 2. Indian Deed for Staten Island, July 10, 1657. Berthold Fernow, ed., Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York, vol. 14. Albany, N.Y.: Weed, Parsons, 1883.

The final months of Stuyvesant’s administration had been a series of losses. Councilors and subordinate officials had lost confidence in his ability to administer the province and guarantee its security against the neighboring English and natives. In Hartford, Connecticut, officials were refusing him the right to the title of governor. And why not? They were already dismissively declaring that they “knew no New Netherland.”2 By the early 1660s, it was clear that he had lost the loyalty of English Long Islanders. In 1664, he showed himself unable to maintain his authority over outlying Dutch settlements. This was especially evident when he most needed such towns as Beverwijck (Albany) and Wiltwijck (Kingston). In the desperate days preceding the English attack, his efforts to draw together an assembly of representatives of the towns had failed. His military position was close to impossible. He had repeatedly failed to convince the West India Company that the garrison on Manhattan Island was in serious need of reinforcements should an English attack occur. When the English fleet finally arrived in late August, Stuyvesant’s efforts to mount defenses around New Amsterdam failed miserably. Diplomatic overtures to the fleet’s leaders were equally useless. They were flung back in his face. His surrender of the province was a reluctant but inevitable acquiescence to too few resources, too little loyalty, and a loss of confidence in his leadership. In its own way, the Englishmen’s bit of graffiti simplified all the history that has been made of the capitulation and subsequent transformation of New Netherland to English rule.

xii Preface

In a final irony, it was Stuyvesant’s West India Company superiors in Amsterdam and the States General in The Hague who bestowed an aura of prophecy on the villagers’ description of the solitary figure. In late 1664, they ordered him home to answer for the loss of the province. Humiliated and carrying sole responsibility for defeat, he boarded The Crossed Heart (Het Gekruyste Hart) and began a journey to the Netherlands and an uncertain future. We have only shadowy glimpses of his state of mind during that time. We know that he took up residence in Holland for three years while the States General and the company decided his fate. He knew that he could either be denied all compensation for years of service to the state and the company, or, worse, face severe fines and imprisonment. In the company’s words, he would get what he deserved “on account of his neglect or treachery.”3 In 1667, he was found guilty of negligence and dismissed. His superiors conceded, however, that if he lived quietly, he could, wherever he chose to reside, remain in his own house on his land, like any other man. Stuyvesant chose to return to Manhattan Island. There he lived peacefully on his bouwerie until his death in 1672. Yet even the courage required to make that choice has gone unrecognized by a number of later historians who have preferred to foreground the magnanimity of the newly appointed English authorities in allowing him peaceful residence.

* * * In the reflections that follow, I want to offer the trope of loss as a way into evaluating Stuyvesant’s career and that of New Netherland generally. I think it positions us to appreciate the precarious zone between failure and success in which Stuyvesant continually constructed his identity and that of New Netherland. It also illuminates the inner resources he had for coping with loss—or those he lacked. Historians are now agreed that were it not for his leadership, New Netherland might not have survived for seventeen years and, in its final decade, achieved considerable stability. Their judgment recognizes the constraints and moments of defeat that bound Stuyvesant tightly over nearly two decades. With hindsight, we can accept the message of defeat the English Long Islanders shorthanded in their depiction of him. We can also, however, extend it backward in time, even to 1647 and the first days of his arrival on Manhattan Island. Hindsight is the easiest (and, by itself, the most unreliable) part of any historical analysis. But there is clear evidence that Stuyvesant himself recognized

The Outcast xiii

that he had bound himself to a career with a company that was never without its tough competitiveness, volatility, and even treachery. He had also bound himself to a precariously placed set of trading settlements where failure was an ever-present reality. His presence in North America was dependent on the sudden withdrawal of support from company directors in Holland—perhaps because of him personally or because of the profitability of their investment. It relied too on their response to the force of local circumstances, always unanticipated. In this uncertain space, Stuyvesant transformed into official practice and the dutiful performances of daily life the structures of feeling and reason available to a seventeenth-century Dutch man. They were not the lifeways of twenty-first-century North Americans. They were premodern structures, and failing to acknowledge this only adds a further dimension to loss. There is, then, something of a misconception in the way New Netherland is placed in the current historical narrative of the United States. In that account, the New Netherlanders (and Stuyvesant among them) were early modern achievers. They developed a successful entrepreneurial culture. By that, they made a positive contribution to and deserve inclusion in a nationalist narrative that accepts nation-building, capitalism, secularization, democracy, and progress as normative values. And each of these values is an element in a cultural phenomenon that we Americans think ourselves particularly well placed to celebrate: modernity. So, the New Netherlanders are precursors of us. They were not premodern. They were not the other. They were us. Bringing Stuyvesant and the New Netherlanders under the mantle of modernity causes us, however, to lose sight of the fact that the affective and rational structures within which they gauged success or failure were premodern or pre-Enlightenment. Yet modernity is a powerful agent in acting as a differentiator between the modern as progressive, secular, and rational, and the premodern as regressive, religious, and therefore irrational and oppressive of others. Identifying the New Netherlanders as people who were not acting out values that would satisfy our criteria runs the risk of opening them to the charge of being a materially and morally backward community. A number of recent scholars have been troubled by modernity’s categorizations. Their studies are important. Debjani Ganguly’s work is an ethnography of the Indian caste known as the dalits. It is written from the viewpoint of theoretical developments in the field of postcolonial studies. In it, she points out that modernity is the staple of current academic social scientific and historical readings of caste. Yet the dalits still struggle to keep alive life-forms in ways where

xiv Preface

the questions of modernity “are not central to the ways in which . . . [they] make sense of their lives.” Living in a culture that is an assemblage of secular and nonsecular practices puts them outside the “secular, progressive, rational way of being, for which the term ‘modern’ is used as a shorthand for public spheres around the world.” Their way of life is denied the moral force afforded to the modern material and moral cultures, because they apprehend being in the world differently from the modern and perform that apprehension in different religious and social ways. They remain the object of disrespect at the least and, at the most, make their eradication thinkable and admissible.4 Ganguly’s aim is not to reject modernity—nor is mine. (In a paradoxical way, a knowledge of modernity provides a significant way of understanding Stuyvesant and the narratives about him.) Her intention is to reject the way the nation-state and social sciences use its categorizations “to interpret everything in their own image.”5 David Lloyd’s concern comes even closer to my own. He analyzes modernity as it is currently used to make sense of the Irish Famine of 1845–1851. In The Indigent Sublime: Spectres of Irish Hunger (2005), he found that modernity empowered a nationalist account that distorted the culture of the famine Irish as uncivilized and pre-political in order to legitimate the modernizing way of life that left it behind. In contrast, his research into the lives of the peasantry during the famine years uncovered a material and cultural space that sustained a viable mode of agricultural organization and a remarkably vital cultural formation. He found that in multiple ways—in modes of “landholding and cooperation,” community recreations, and the “organized struggles and cultural activism that marked the century following the Famine”—the Irish retained the memory of “a richer Gaelic culture” than has been transmitted. Lloyd’s study presents a tug-of-war between an interpretation of a premodern Irish population whose vitality refuses to be laid to rest, and one that invokes modernity as the best tool for effectively denying that vitality by achieving forgetfulness.6 In reflecting on Peter Stuyvesant and the New Netherlanders, I want to join Ganguly and Lloyd in rejecting the use of modernity as the consummate test for the vitality and moral worth of a people. I also want to apply Lloyd’s thesis to the modernizing process in American history—contending that it too enacted a self-legitimation by achieving forgetfulness of New Netherland culture. That forgetfulness is not erased by selectively excising out of it a trace of proto-capitalism. Doing that is, in fact, fixing one more chain to those already binding Stuyvesant to an enduring but skewed historiography.

The Outcast xv

The real test, as I judge it, should be to examine the degree to which Stuyvesant and his contemporaries lived good lives within the limits of their times. For them, those times were largely premodern. Nation building, capitalism, secularization, democracy, and progress were not normative values. In Stuyvesant’s case, the loyalties he required of himself, especially to the West India Company and the States General, were central and were more postReformation than they were modern. So too was the constancy with which he acknowledged the force of tradition and the presence of the supernatural and providential. These were binding obligations and binding beliefs that he allowed to direct his life. With them, he would have measured his own success or failure and, I suspect, would in the end have judged himself a success—as I do.

* * * Stuyvesant constructed his life on many fields of experience. I am aware that in this essay I am neglecting several possible ones—for example, his immersion in networks of family and friends or the sphere of diplomacy to which he put considerable energy. I am, however, asking you as readers to consider three. Each pressed heavy obligations upon him—especially because he was a dutiful man. They are: first, the responses to the duties his oath as a senior officer in the West India Company entailed; second, his experiences as a believing Christian; and, third, his life as encounters with loss. I am asking you as readers to consider these—duty, belief, and loss—as major narrative themes in this book. Here they are presented sequentially, but not meant, by that, to be free-standing or independent of one another. On the contrary, and as I hope you will discern, they are substantially interwoven. For the seventeen years when he was administering the province of New Netherland for the States General and the West India Company, Stuyvesant was scrupulous in his fidelity to his oath of office. He appears never to have questioned the sacredness of it. He never allowed himself to profane it. Rather, and in a way that we might find excessive, he accepted its binding power even though officials at The Hague and company directors seldom returned such loyalty and certainly deserted him in 1664 to 1668. Stuyvesant’s oath provides a way of coming to understand his seventeen years as chief magistrate in New Netherland. I write about that in Part I, Duty. From what the documents tell us, he was acutely aware of the authority vested in that role. His authority was dual in its nature. It was both civil

xvi Preface

and ecclesiastical. It was settled in a newly emergent (and therefore untried) dispensation of European Christian communities following the Reformation. He began his administration only ninety or so years after John Calvin himself drafted the last version of the Institutes (1559), that is to say, a mere four generations after the deaths of the great Protestant reformers. The 1578 Alteratie by which the rule of the city of Amsterdam was transferred from Catholics to Protestants had been invoked only thirty-two years before Stuyvesant’s birth, or sixty-nine years before his arrival on Manhattan Island. Stuyvesant’s determination to exercise his role as a magistrate, as he understood it, aroused sustained political opposition in New Amsterdam. This was especially the case during the first half-decade of his administration. This period of contestation from 1647 to 1653 requires close attention because in it lay the first and strongest ties that continued to bind him to a largely negative reputation among later historians and other commentators. From that halfdecade forward, his responsibilities as chief magistrate took him to affairs beyond Manhattan Island. There he shouldered the company’s obligation to institute successful networks of trade, settle orderly civil government, and defend the province’s people against native and European enemies. So the decade from 1654 to 1664 allowed the Englishmen at Vlissingen to locate in his person the public will of New Netherland. Perhaps this personification was a myth to be peddled as necessary—for example, to satisfy expectations of leadership held by local natives. But in many ways, it was also a reality. Stuyvesant used his oath as an enabling instrument of authority. But it would have lacked efficacy, would have had no justifying aura, had it not held a place within a wider structure of belief explored in Part II, Belief. I try to look at two dimensions of belief expression. First, there were the everyday, noninstitutional religious practices by which he and other New Netherlanders made efforts to access God in their everyday lives. In the first chapter of Part II, then, I consider the construction of a nonsecular cultural formation but focus on everyday practice, that is, personal spirituality. The evidence for individual expressions of belief is, of course, fragmentary. This is due to the character of the archives, the social construction of early Calvinist practice, and the taken-for-granted enactments of religious belief. But much can be learned. One of these fragments of belief can be found in a 1638 document. In that year, a wealthy and tough-minded Dutch merchant took up a sheet of paper. At the top, he wrote, “In the Name of the Lord . . . in Amsterdam.”7 In my judgment, the merchant was momentarily making God present to himself. He

The Outcast xvii

was trying to establish or reconfirm a relationship, using inscription to arouse presence. This performance brings to light something he took for granted. It is something about life lived in plural temporalities. From the analytic viewpoint, such a performance is mystifying. But this is so only if some modern logic is allowed to override the evidence, translating it as somehow incidental or dismissing it as if just formulaic. Or it is dismissed if everyday secular practices and religious belief are taken to be fixed opposites rather than interpenetrating. The unexpected presence of the fragment of spirituality is, in other words, an inconsistency. It either needs to be explained away as a cultural oddity or must be recognized as exceeding the generally accepted secular categories of the social sciences. The fragment opens the possibility that the merchant was neither hopelessly tethered by the obligations of belief nor burdened by religious practices. Instead, he was empowered to consider himself made whole. Second, Stuyvesant and his council issued provincial thanksgiving and fasting ordinances on a regular basis. These were political performances of belief. I introduce them in the third chapter of Part II. They were political moments made theological. In the ordinances, Stuyvesant called for a collective response to either tragedy or well-being. They activated a sense of divine presence. Each pronouncement also recuperated the force of previous proclamations. They bound his magistracy to the community in ritualizations of the inseparability of divine intervention and man-made law. He bound himself to performances that kept the distant provincial communities emotionally and spiritually connected to the sequence of dramatic events with which his administration was dealing. The ordinances should be taken seriously. They are not decorative. They are not moments of time-out between the real business of business. Nor does reference to Stuyvesant’s so-called stubborn Calvinism, I think, explain their style or substance. Instead, they present a range of meanings: medieval Catholic and Reformation survivalisms, characteristics particular to New Netherland culture, and (most valuable for this study) Stuyvesant’s intimate implication in the initiation and production of these remarkable premodern texts. The ordinances are instances of the connection between political and providential histories consciously brought together in a plurality of rhetorical forms: didacticism, Reformation devotional language, encounter narrative, prayer, practical and biblical imagery, and so on. In wording and substance, they changed little over the seventeen years. In that, they provide insight into Stuyvesant’s perception of himself, his people, and the course of New Netherland’s history.

xviii Preface

Thirdly, loss was central in the life of Stuyvesant and the history of New Netherland. There are several analytic orientations available and I offer them in Part III. Stories have been made of Stuyvesant’s life for 350 years since the Long Islanders made metaphor of him in 1664. In one respect, the narratives represent what scripture scholars call backward formation. The earliest commentators on Jesus of Nazareth’s life paid most attention to the last weeks of his life. Only gradually did they fill in and textualize the years of his ministry and, more latterly still, the birth and childhood years. So too and in many ways, it is Stuyvesant’s last months as director general that have attracted attention. It is the period when he appeared to be an outstanding failure. And that has been allowed to set the stage for questions about the success or failure of New Netherland as a whole. Only in the late twentieth century have scholars begun to register their dissatisfaction with such incomplete representations of Stuyvesant. Jaap Jacobs, for example, has given us some of his early poetry, pinned down his place of birth, and joined others in filling in biographical detail. Willem Frijhoff has written beautifully about his Dutch pietism. Most important, Frijhoff has taken seriously the ways pietism informed the young lives of men such as Stuyvesant. Like other leading historical figures, Stuyvesant has been chained to the vagaries of American historiography’s own history. As we shall see, he was tied to a paradigmatic conceptualization of American colonial history that severely limited the human diversity that marked the seventeenth century. He was also fettered to the myth-making that plays its part even in socialscientific history writing and deserves greater attention. So in Stuyvesant Bound, I am writing about loss, failure, betrayal, and misrepresentation. I am not, however, writing about the tragic. Stuyvesant’s life was not a tragedy. Being-bound, as Martin Heidegger has pointed out, is the positive meaning of human existence. The final pages of Stuyvesant Bound deal with the ways in which the many meanings of loss, being-bound, the mythic, and tragedy come together for our present-day understandings. They may be of value for American readers should they experience a sense of loss as their cherished certainties fail to “take” in the welter of today’s complex global communities.

* * * In the fragment of verbal graffiti, the abject outcast is not presented as an abstraction. The Long Island men situated his powerlessness in everydayness,

The Outcast xix

in the experiential, in the emotive, and in his body. Their words call us to witness fluid relationships—Stuyvesant bound to the captors or captor who tied the ropes, Stuyvesant joined to the known land of the past and unknown land of the future, and Stuyvesant bound together with Englishmen and natives in the tangle of a cultural performance, the description of which is

Figure 3. Peter Stuyvesant, attributed to Hendrick Couturier, circa 1660. New-York Historical Society.

xx Preface

universal—the outcast—and yet true to the tragic singularity of the moment and context of its telling. For a representation that is meant to function as an abstraction, we might turn to the seventeenth-century portrait of Stuyvesant ascribed to Hendrick Couturier (Figure 3). The painting presents him in control. It gives no hint of a man having experienced loss. Indeed it suggests command by portraying immobility. Its purpose is not to feature experience at all. Stuyvesant’s body, in which relational existence takes place, is effectively erased in order to achieve a posture of authority. It is authority beyond the reach of historicity and contingency. It resists those particularized moments that might disturb invulnerability and self-assurance.8 In this volume, I use the description I am calling “graffiti” as a recurrent motif. Its theater allures us into reflecting on the trope of loss. It points us toward a performance that makes present both the universal and the particular. In the words of Charles Altieri in 2007, a work of art should “put before our eyes a content, not in its universality as such, but one whose universality has been absolutely individualized and sensuously particularized.” If universality is emphasized only with the aim of providing abstract instruction, he continues, “then the pictorial and sensuous element is only an external and superfluous adornment.” No, the senses must be written-in as “an inseparable aspect of experiences that [then] take on metaphoric power.”9 In presenting Stuyvesant as a seventeenth-century individual undergoing the experiences of magistrate, believer, and defeated leader, I hope I have not made a pretense at understanding his life entirely. But I have attempted to offer his life as having meaning outside itself. I hope I have given it, in Altieri’s words, metaphoric power. I mean: it has given some measure of meaning in your life.

Stuyvesant Bound

This page intentionally left blank

I

Duty

This page intentionally left blank

Chapter 1

Magistracy and Confessional Politics

It was not an auspicious beginning. For fifteen days in summer 1646, the States General had delayed confirmation of the West India Company’s appointment of Petrus Stuyvesant as director of New Netherland. Fifteen days, of course, would prove to be a trivial period of time compared to the almost thirty months eighteen years later, when, from 1665 through 1667, he would await the same body’s decision on his guilt or innocence for losing the province to the English. Now, issuing their approval, the men at The Hague had nothing particularly complimentary to say about him. Nothing to say, really, one way or the other. They were finally authorizing his commission because he was “very urgent to depart.” In accordance with custom, Stuyvesant appeared before the assembly of the States General on July 28, 1646. Formally and before God, he “took . . . the proper oath.” In “all that concerned his office,” he held himself “bound and obliged by his oath, in Our hands.” By it, the thirty-four-year-old man became, as the commission concluded, “Our Director.” An oath was a sacred undertaking. Properly understood, it made nonsecular such responsibilities as those now conveyed to Stuyvesant. He must administer “law and justice . . . civil and criminal”; direct all matters pertaining to commerce and war; promote and preserve “treaties . . . alliances, trade and commerce, and the maintenance of population.”1 Stuyvesant remained aware of the sacredness of his oath of office until he was officially relieved of responsibilities in 1667. On more than one occasion in the years after summer 1646, he called on it, pointing to a quality with sacred meaning with which, in New Netherland, he alone had been endowed. It was an empowerment that resulted from a solemn performance in which only he had been chosen to participate. Two ministers in New Netherland made the connection between his oath

4

Chapter 1

and his conduct as director over the years. Experience in New Netherland had convinced them that Stuyvesant’s loyalty to his oath was the safeguard of public order in the province and the strength of the Reformed congregations. They reported to the Classis in Amsterdam in 1653 that he would “rather relinquish his office” than (to cite their example) grant Lutherans public worship. He holds it to be “contrary to the first article of his commission, which was confirmed by him with an oath.”2 Over his years as administrator, Stuyvesant refined the meaning of his oath. He used it (directly and indirectly) as leverage against his enemies on Manhattan Island. On one occasion in a debate with colonists about land ownership, he cited his obedience to his oath—his “instructions”—as responding to a higher claim than following reason. He admitted that reason was on the colonists’ side. But he could not support them in their plans because, he said, it would require an act of infidelity to his oath.3 Stuyvesant also cited his oath to establish equal status with governors appointed in New England. In 1647, he reacted fiercely to what he took to be personal insults directed at him from the governor and deputy governor of New Haven, Theophilus Eaton and Stephen Goodyear. Eaton, he wrote to Goodyear, had devalued his office as director in New Netherland and trotted out all his faults “as if I were a school boy and not as one of like degree with himselfe.” Certainly Eaton was privy to the many criticisms of Stuyvesant then circulating on Manhattan Island.4 Or perhaps he knew that, over the previous years, the director had been holding junior positions in the Caribbean islands and never attained anything like the position of governor general. Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen had been given that title in 1636 when appointed to Brazil (with a salary of 18,000 florin plus 6,000 florin for immediate expenses and table money). Even now, Stuyvesant had only the status of director general, with a salary of about 3,600 guilders.5 In any case and in the same letter, Stuyvesant took care to apply to Eaton— and implicitly himself—his definition of a governor. They were men of more “noble worth” than others. He reiterated that by their office he and Eaton were “of like qualities.” Earlier he had reminded Eaton of their mutuality in respect to accountability. I took the position I did, he insisted, because I have to give account to my superiors and be judged by them. If I should “in the least measure” transgress in observing their commands, “you know (and I know) that my life, estate and reputation are at stake.” Writing to Eaton later, he explained his actions in language that expressed a relationship that transcended his pledge to his superiors. He was discharging his “duty to God.”

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 5

And one month before, he had written to Governor John Winthrop, again calling on his “bounden Duty to God.”6 Stuyvesant’s oath was available to him as a frequent rhetorical referent because it marked a man. A man who had taken an oath had no relief from that mark until discharged from his office. It brought into being a permanent quality. On one occasion in 1659, Stuyvesant had reason to consider the relative merits of obedience exercised because of an oath, and obedience offered as an exercise of free will. A Dutch officer on the Delaware River had put just such a distinction to him. In a letter to Stuyvesant, the officer said obedience offered on account of free will had superior merit.7 But Stuyvesant’s chosen way was to act out of individual conviction and also on the basis of derived power. In the coming years, he would come to recognize that the scope of his oath was subject to expansion and contraction. His decisions as well as changing circumstances would continue to lift an initially untested enunciation off the page of the States’ commissie-boek and give it actuality. In the end, the final performances of it would be enactments humiliating and tragic.

* * * When Stuyvesant arrived in New Netherland in 1647, he knew something of the opposition that was about to test his steadfastness. Well before this time, the company directors had been made aware of a rising tide of complaints against its governance on Manhattan Island. They had shared these with the States and undoubtedly with him. But Stuyvesant was intelligent, sufficiently competent in the law to trust his own administrative skills and, above all, experienced. He had had cross-cultural experiences that none of the men on Manhattan Island—some of whom would soon be his enemies—could match or, possibly, imagine. For almost nine years, from 1635 to 1644, Stuyvesant’s service in the company had taken him to the southeast coast of Latin America and the Caribbean. Both were among the most unstable areas in an expanding world of European interlopers eager to seize possessions and exploit the local products awaited in Europe. Had he our hindsight about the nature of this wild coastal and island world, he might have recognized that he was caught up in a long phase of world expansion when no one knew what form of colonial venture would prove stable or profitable, “so men who grasped the enthusiasm of the age tried them all.” And in that chaotic world, trade factories and other

6

Chapter 1

parasitic forms of settlement (including those of pirates and plunderers) were not the exception but the rule.8 Stuyvesant spent his nine years in such trading stations. He served the company first on the island of Fernando de Noronha and for the final five years on the mercantile island of Curaçao, forty miles from the coast of Venezuela. His promotion to director general in New Netherland was, in effect, an appointment to just another trading station. Certainly it was more complex than Curaçao and Fernando de Noronha (about which commentators can say little more than that it was rat-infested) but similar in purpose and structure. If we stand back from the little evidence we have of those years and ask what Stuyvesant learned from his Caribbean experiences, we may safely put them under two considerations. First, as a young administrator he learned to deal with the volatility of the West India Company and to accept that he was enmeshed in the mobile and often unpredictable weave of its opportunistic policy-making. He also learned that native populations were essentially heterogeneous and subject to their own histories and intentions. Stuyvesant learned that the company’s aims had thrust him into an inclusive world of strangers. They were peoples culturally, linguistically, and racially different. Each group intersected with the others and with him—Portuguese, Spaniards, Caribs, English, and Africans. Just as the company sought out exploitable harbors and straits, so it reached out for strangers whom it could exploit. Some it hired as employees. On Curaçao, Stuyvesant worked alongside several Englishmen and was witness to natives being sent into the countryside on company business. Others were taken on as useful allies: the Aruba natives to whom Stuyvesant offered protection because they had aided militarily in a confrontation with the Spanish at Maracaibo, the natives of Bonaire working the salt pans, and those who passed on information about mines and minerals.9 Beyond the employees and allies were the company’s enemies (also of many nations). But all were measured for their usefulness to the company’s trading enterprises. Regarding Stuyvesant’s intellectual curiosity about the natives of Curaçao, we have only one clue. On one occasion in New Netherland in the 1640s, a group including himself and Domine Johannes Megapolensis turned to discussing the “Caracks.” Perhaps they were exploring the minister’s special interest in the origins of non-European peoples. Perhaps they were entertaining a curiosity about the differences among native peoples then being inventoried by naturalists. This categorizing endeavor may in turn account for the name of a ship plying its trade between the two locations from 1660 to 1662, Den Nieuw Nederlandsche Indiaen.10

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 7

Stuyvesant learned to take on some of the company’s strategies. After being promoted from commissary to provisional director of the station on Curaçao, for example, he put into effect a tactic that company directors called upon again and again: turning a loss into a gain. In one instance, he identified those who were soldiers among the 450 company personnel harboring at Curaçao after the fall of São Luis in the Brazilian Captaincy of Maranhão in 1644 and sent them on to New Netherland to assist Director Willem Kieft’s hostilities against the natives there. He also learned to reward native allies. In 1643, he and his council removed a number of loyal natives from Aruba to Curaçao for protection. Two months later, he granted permission for some of them to return to Aruba to see to their livestock and families. He learned that protecting natives meant enforcing a geographical distance between them and dangerously undisciplined Dutch men.11 In short, Stuyvesant learned to identify himself as the States’ and company’s servant. Neither then nor later did he make a claim on any other binding identification. Publicly he never claimed to belong to a town in the Netherlands, nor to a province or an extended family. Jan Pietersz Coen, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, and Willem Bontekoe—who sailed for the East India Company almost a generation before Stuyvesant set sail for New Netherland—each boasted of belonging to Hoorn. David Pietersz de Vries, who sailed some years after them, did as well. Other near-contemporaries such as Kiliaen van Rensselaer and Johan Mauritz van Nassau-Siegen obviously chose to wear their identification at all times. Stuyvesant’s predecessor in New Netherland, Willem Kieft, seemed to identify himself with a broad family network that included members of the regent class in Amsterdam, and in fact he interpreted his commission as empowering him to act as a regent on Manhattan Island as well. In my judgment, Stuyvesant settled for identification with the company until about 1662, when he became a New Netherlander. That is, he realized that he was looking at New Netherland from a substantially different perspective than the company. And that conviction remained with him from that time forward. As for time backward—biographical time before Fernando de Naronha and Curaçao—a seemingly different young man confronts us. Stuyvesant was a university student preparing for the ministry in Franeker in Friesland. He studied theology, began to learn Latin, read the early Church Fathers, and enthusiastically embraced Calvinist pietism. After about two years and for uncertain reasons, he determined not to proceed to the ministry. At the age of about twenty-one, he left the university and soon joined the West India Company. As we shall see, he really did not leave Franeker behind at all.12

8

Chapter 1

On Curaçao, Stuyvesant began to learn that the company directors would measure their man carefully. They let it be known that theirs was the task of devising plans and backing them up operationally. His was that of implementing those plans by his resourcefulness, youth and physical endurance, and loyalty. In each of his letters and reports, he affirmed that he understood this. The directors were also aware that governing overseas was a matter of governing emotions, those of the company’s servants and those of the native peoples they encountered. Here on Curaçao and during the seventeen years of his governing in New Netherland, they maintained a tight surveillance on Stuyvesant’s sentiments and moods as they influenced his decisions. Knowing that the two were interlocked, they chided him on one occasion, for example, for his “compassion” as against the maxim that everyone is “bound to care for himself and his own people.”13 At other times, they were quick to call him arrogant but, then again, reproach him for not being tough enough with those protesting against him. They watched for signs of insufficient steadfastness and of wavering. Stuyvesant learned to preempt any accusation of reliance on his imagination.14 Concern for his emotional compliance with their directives informed every letter from Holland. The directors recognized their own overwrought emotional responses whenever they perceived Stuyvesant’s failure to send adequate documentation about the trade or his unsatisfactory handling of individual crises. Such occurrences, they often warned, excited in them strong emotions. And indeed they did. The archive of their correspondence with Stuyvesant is certainly one of purposeful professionalism. But I have come to think that we misjudge it entirely if, by the fact of the directors being businessmen, we consider it exclusively running down the tracks of rationality. In fact, it is nothing less than a bundle of impending or half-settled reproaches, sometimes sly, often direct, but always threatening. Stuyvesant, in his turn, constantly gauged their moods. And as a mariner looks out for the changing moodiness of the sea, he also watched for those of the colonists and natives. Of the colonists, he wrote that they could be fickle. He watched carefully for this, measuring it even to the days of the surrender in 1664. As for his reading of the natives, his advice to the Massachusetts governor in 1651 is characteristic. We need to be patient with them, he advised. Their “spirits” are not yet adequately subdued nor their “affections” yet won over.15 But, as with discerning the tempers of the sea, mastering such a reading took time and experience. His correspondence with Willem Beeckman, vice- director on the Delaware River, repeatedly demonstrates his awareness of this.

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 9

Stuyvesant’s identification with the company should not be construed as evidence that he trusted it or expected its loyalty. If loyalty meant provisioning a station adequately or sending sufficient soldiers for the proper defense of its men and workers, then it was not a quality the company considered a priority. In 1644, Stuyvesant found himself without the basic provisions for soldiers who were made useless without them. Here was a foretaste of his soldiers without stockings, shoes, and shirts, as he would later complain in an emotional outburst in 1659. More important, military unpreparedness was a portent of the single most divisive issue that would arise between the directors and Stuyvesant later in New Netherland since it went to the heart of the survival of the province and its settlements.16 Similarly, the directors were not expressing confidence in one of its servants when they offered the customary directive: you are the man “on the spot”; you make the decision. It was a way of removing themselves from blame should things go wrong.17 This practice is of consequence in evaluating Stuyvesant’s reputation among later historians. As only one example, in an early letter to Stuyvesant, the directors painted themselves as distant from the opposition facing him in New Amsterdam. They were prepared to leave the impression that it was entirely his acts that had, as they worded it, aroused “the hatred of the people.”18 So employees such as Stuyvesant had to learn how to protect themselves. They would soon enough discover that corresponding with the company was nothing less than a defensive craft they had to master. A subordinate needed to become adept at artful evasion. He had to find the balance between fawning and self-assertion. He had to appear compliant with the company’s domineering and, at times, pointedly humiliating rhetoric. Getting everything in writing was a common tactic of self-defense.19 After being wounded on the island of St. Martin and before sailing to Holland in 1644, Stuyvesant insisted that his secretary copy the Resolution Book of Curaçao of 1643 and 1644. This, he advised his councilors (not for the first time), was “for their own justification.” He carried the book with him when he arrived on Manhattan Island in 1647, and it was among his papers until the English takeover.20 In any altercation with the company, it was better to have your words thrown back at you than to have no words at all. So it was with Stuyvesant after the fall of New Netherland in 1664.

* * *

10

Chapter 1

New Netherland’s leading historians would be in agreement with Charles Gehring that all Stuyvesant’s political and military skills were needed after 1647 to hold the province together. Furthermore, with these skills, he resolved most of the problems encountered during the first five years of his administration.21 Those years presented Stuyvesant with a landscape of loss rather than some horizon of expectations. New Netherland was not a mass of possibilities but a field of disasters. His immediate predecessor, Willem Kieft, had warred intermittently against the natives for about five years. The fighting left Manhattan Island and the surrounding villages devastated. Back in Holland, the company directors were in denial about the war. They could not even bring it into coherence as an event. But the destruction was real. The loss of lives on both sides, ruination of properties and entire native villages, and disruption to previously reliable Dutch-native trading networks and overseas trade, these were all extensive. Still, they were only some of the outward expressions of the breakdown of authority and, with that, the collapse of the possibility of vision, trust, and rebuilding that established authority puts in place. From the sources we have concerning this half-decade, it is tempting to conclude that not Stuyvesant but sheer contingency was ruling New Netherland. It appears, first of all, that its survival depended on the energy he exerted putting out unpredictable spot-fires and making on-the-run decisions: now handling the uncontrollable disorder along the South River (Delaware River), then dealing with potential breakaway English settlements on Long Island, here in New Amsterdam confronting a man determined to murder him, there reacting to the threat by a Dutch trader living at times on Staten Island with armed local natives and known to have told them that Stuyvesant would soon build a wall around New Amsterdam and come to kill them. Therefore they should “murder the Director.”22 There were blazes to put out regarding merchants who were regularly smuggling guns and liquor to the Raritan, Mohawk, Munsee, and Susquehannocks. And flames were burning at Rensselaerswijck, where he and the independent-minded director of the patroonship were locked in bitter confrontation (Figure 4). The records also suggest that New Netherland was living under another sort of contingency, the rule of government-by-correspondence. In other words, compounding reliance on contingency-driven policies on the ground was dependence on the equally unpredictable and swerving policy directives sent to Stuyvesant by the West India Company. It can seem that no nonnegotiable legal or political principles were at hand to bring into

Figure 4. New Netherland, circa 1660.

12

Chapter 1

order, prior to their occurrence, the exigencies of circumstance, the possible misjudgments of Stuyvesant himself, and the short-sighted misrule of a distant corporation. Finally, the documents lead us to think that daily experience was the immediate cause for legislating and executing the law such as it was Stuyvesant’s obligation to enforce. In each ordinance, he sought wording such as this: “The director general and council of New Netherland, seeing and observing by daily experience . . . hereby ordain . . .” The justification for promulgating an ordinance or bylaw rested on existential evidence of its present necessity.23 Law did not rely on the weight of precedent but on the experiential. As a result, circumstance floods into the provincial records, even as it does into those of local inferior courts. Stuyvesant, however, did come to New Netherland with firm legal and political principles set in a philosophy of government at home. Discourse on the principles of “true liberty” and “the common welfare” was in the air. His papers are filled with references identifying fundamental postulates of good government generated out of political contexts historically specific to the Netherlands and regarded by him as a body of law he was ordained to institute. His words on this important matter leave no doubt that, from the beginning, he saw himself at the center of authority. He quickly pressed the point that New Netherland was a province with rights and privileges. In 1649 he designated himself “chief magistrate” of “this Country.”24 Elsewhere he claimed that executive, legislative, and judicial power resided in his person; he was (as his oath allowed) “Director and chief judge.”25 Stuyvesant repeatedly demonstrated that he had a solemn obligation to enact the same order of governance in New Netherland as existed in the Netherlands. On two occasions, he cited it as “the general civil and ecclesiastical order of our fatherland.”26 In law and in practice, the two spheres identified in the wording—civil and ecclesiastical—were not separate: both fell under the magistracy. Again and again, we see Stuyvesant interpreting them this way, and understandably so. As magistrate, he was bound by oath to exercise authority over both of the spheres that constituted the order of the fatherland. By this, the religious dispensation and the political order of New Netherland were both, as was intended, attached to “a relation with the sacred.”27 Stuyvesant’s implementation of this order, then, was not simply the result of a tyrannical temperament or an allegedly implacable Calvinist disposition. Both of these criticisms have been marshaled against him by historians. His exercise of the two powers of the magistracy was a juridical survivalism that derived

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 13

from the time of the Reformation and even pre-Reformation years. Lawmaking was simply not a secular enterprise. Much more needs to be said later about these immediate post-Reformation decades. But if we, for one reason or another, have allowed the consequences of the Reformation to slip out of mind in our analyses of Stuyvesant and New Netherland, contemporaries certainly did not. It was, of course, precisely to “the Dutch reformation,” for example, that an English minister in New Amsterdam—someone who would have understood the dual role of the magistrate full well—appealed when seeking “freedom of conscience.”28

* * * In his seventeen years in office, Stuyvesant was enacting confessional politics. This is a term used today to designate the political structures devised by European powers to meet the changes brought by the Reformation. Unlike the Europeans at home, Stuyvesant had no need to make religion the basis of his policies toward external enemies. Confessional politics were only a marginal concern with respect to distant Catholic Spain and Portugal. Nor was the Catholicism of New France a primary consideration in his relations with the French along the St. Lawrence River. His closest neighbors, the English of New England, Virginia, and Maryland, were indeed enemies but (for the most part) conventionally Protestant. But he did have to manage religious confessionalism within the province. Although Calvinist doctrine and practice was far from being the established church of the Netherlands and therefore New Netherland, it was the only confession authorized to conduct public worship. So colonists of other religious creeds (some of them troublesome)—Lutherans, Jews, Quakers, and a few Catholics—needed to be dealt with as well. What we are seeing in Stuyvesant’s administration, then, is a public official accepting the religio- secular character of post-Reformation politics, an official who is expecting that reality to make claims upon him as “chief magistrate . . . of this Country.” Across the Netherlands, the religio-secular character of magistracies such as Stuyvesant’s was everywhere in evidence. Individual magistrates and their councils delegated to themselves the power to determine the degrees of separation that would exist between the “civic and ecclesiastical order.” Willem Frijhoff has shown how the management of this separation worked (or failed to work) in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in a number of Netherlands towns. His data show that, despite the determination of a town

14

Chapter 1

magistrate to absent himself from church matters or make only minimal interventions, the structure was such that entanglement was far more likely than strict separation of a town council and local governing church body, whose members were in any case likely to be the same individuals. Autonomy was a privilege neither body had or could expect.29 In New Netherland in 1628, Domine Jonas Michaëlius worried about a request that he act as a councilor. He felt that political and ecclesiastical offices “must not be mixed but kept separate.”30 From 1645 to 1647, Kieft clashed with Domine Everardus Bogardus in a bitter, prolonged, and unresolved debate about the sphere of authority over which each had primary control. The personalities of the two men and the immediate circumstances of the events certainly exacerbated the vehemence of the clash. But the origin lay in a more fundamental factor. Like the ecclesiastical sphere with which it structurally overlapped, the political order sited in the magistrates was also attached to a relationship with the sacred. Magistrates took oaths solemnizing this bond. People expected to see this worked out in their daily decision-making. The trafficking of a magistrate into the decision- making of a minister or local consistory (and vice versa) was a familiar manifestation of the porousness of the boundary between civil and ecclesiastical power bases. One physical sign of that porousness in New Amsterdam was the handelskerk. The Dutch trading companies insisted that a church be erected in overseas establishments. As in other outposts, New Amsterdam’s handelskerk was situated within the fort under the director general’s direct control. Stuyvesant acted as the congregation’s churchmaster; at one time one of his councilors was church warden.31 Over many future decades of secularization, this boundary would become far more firmly settled. But it was not smoothly worked out in the civil culture of the time. This was the borderline that Domine Michaëlius feared he would be called on to cross (and he was). It was the space acrimoniously crossed by Director General Kieft and Domine Bogardus. In 1649, Stuyvesant and New Amsterdam’s preacher, Domine Johannes Backerus, traversed it in anger as well.32 When such border-crossings were quarrelsome, they betrayed a mismanagement of a Calvinist regime and a Calvinist dispensation. To townsmen, they undercut an edification to which they felt they had a right when the two authorities intermeshed properly. Townsmen fully expected, for example, that a man or woman facing criminal charges in Stuyvesant’s court would, during its sitting, not be allowed to receive Communion. They also desired variations of the protocol suggested by Stuyvesant in 1660 for building a house for the

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 15

newly appointed minister in Breuckelen (Brooklyn). For the best result, he advised, “let the work go forward under the supervision of one member of the church consistory and another from among the town’s magistrates,” that is, “that Moses and Aaron would stand together.”33 Equally acceptable were the fusions of the secular and the religious that Stuyvesant made in citations put forward in two legal cases he undertook two months after arriving on Manhattan Island. The first case involved crimes allegedly against his legitimate authority committed by two men. In pursuing them in the court, Stuyvesant summoned both secular and religious authorities to establish his legal position: Joost de Damhouder and Johannes Bernardinus Muscatellus, but also Exodus, Ecclesiasticus, and Romans. He expected this mix of secular and religious references to be entirely acceptable. In the courts, legal and theological discourse had always interpenetrated.34 The exchange, however, had its limits. In 1660, the company expressed dissatisfaction with a judgment handed down by the authorities appointed to the city of Amsterdam’s colony on the Delaware River. The local officers had blurred the line between legal fault and sin. Allegedly, they had required a man accused of fraud to “ask pardon of God and justice” rather than face the customary penalty. This, the directors charged, broke with precedent in “our Fatherland.”35 In the breach, however, the case was a manifestation of an inseparability of spiritual and secular that was still unquestioned in a Dutch way of life of which civic culture was only one element. The decision-making terrain, then, that Stuyvesant felt was rightfully his to enter as magistrate was civil-ecclesiastical. He was expected to be managing Calvinist doctrine and practice in New Netherland as much as, say, customs regulations. Lawmaking was often, in present terminology, religiously inflected. As Kathleen Davis has written, following the Reformation, What is our purpose sub specie aeternitatis? was a question that politics now—following the breakdown of aspects of the old religion—had to ask and answer.36

* * * Stuyvesant’s management of the Calvinist (or, better, Reformed) dispensation in his jurisdiction was comprehensive in scope. This was undoubtedly because he was prepared to impose, as it were, a loose interpretation of his rights and obligations as administrator of New Netherland. But it was because, in the Netherlands and elsewhere, Calvinist clergy had chosen to divest

16

Chapter 1

themselves of governing authority in many areas and confer it on the magistracy. As other magistrates did, Stuyvesant paid ministers’ salaries and arranged for and paid the local schoolmaster. In 1652, he initiated moves to obtain a minister who could preach in English and reserved to himself as chief magistrate the authorization of a minister to preach outside his congregation.37 Cases regarding marriages, orphans, and bequests came before his bench. More substantially, he accepted Calvinism’s willingness to invest the magistrate’s court with the supervision of the laity’s morals and the extraordinary power to command obedience and, in effect, enforce morality. Stuyvesant’s management of Calvinist doctrine and practice was also exemplified in a series of decisions and pronouncements made between 1657 and 1659. In August 1657 the Woodhouse had arrived off New Amsterdam carrying a number of Quakers. In the early seventeenth century, these sectarians were among the most anti-authoritarian dissenters in Christendom. Stuyvesant and his council made the ship move on to New England. But two women stayed behind, and their extraordinary behavior immediately disturbed the populace and resulted in their imprisonment for two to three days and subsequent banishment.38 The troubling actions of the women also unsettled two of New Amsterdam’s leading ministers, who informed the Amsterdam Classis of the disturbing events. They described the women’s actions in considerable detail, comparing them with disturbances in the churches in Europe.39 The clerics’ suggested remedy invoked one of the devices meant to prevent confrontation: sectarian isolation. A number of principalities across Europe had experienced a bloodbath during the religious wars starting in the mid-sixteenth century. As a result, local rulers and magistrates had slowly come to accept the endurance of confessional differences and the advantages of legislating territorial isolation of the disputing parties from each other.40 This incident has been interpreted by a number of commentators. But I think the core of its meaning is to be found in a piece of correspondence received by Stuyvesant about six months later. In 1658, the governor of Canada wrote from Quebec welcoming the Hollanders to French Canada. But he forbade the “public exercise on land of their religion, which is contrary to the Romish.” He assumed that Stuyvesant knew how confessional politics was operating in Europe. “You know,” he wrote, “the order of the King about this matter.” In New Netherland, the two ministers also put the link between confessional differences and geographical separation quite simply. The New Amsterdam community had “the truth,” and only the removal of the nonconfessing individuals would “preserve” it.41

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 17

Isolation from nonconfessing individuals and groups was also Stuyvesant’s solution. In post-Reformation times, it was achieved in two forms, and he utilized both. He implemented a form of the juridical territorialization of religion first expressed in Europe at the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, reaffirmed in the 1648 Treaty of Munster in cuius regio, eius religio (whose rule, his religion), and now implicit in the ministers’ words. Individual towns in the Netherlands had, for example, the power to deny full citizenship to inhabitants unlike themselves, that is, of different religious beliefs. Similarly, it is clear that the villagers of Rustdorp (Queens) on Long Island wanted to be rid of the Quakers who had come into their village and expected Stuyvesant to remove them.42 Now, in 1657, Stuyvesant and the council were also enforcing the policy of banishment, as he had done in a number of earlier cases.43 About eighteen months before the Quakers arrived, a number of Independents among the English townsmen of Vlissingen (Flushing) were found to be meeting in public conventicles organized by an unlicensed preacher. Commenting on them, Stuyvesant described a scene that would have elicited a reaction similar to ours on hearing of someone practicing surgery without credentials. The man had not only presented an exegesis on God’s holy word, he had also administered the sacraments, offering “the bread in the form and manner in which the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper is usually celebrated and given.” Stuyvesant and his council banished both him and the local enforcement officer who had allowed the meeting.44 The incident in Vlissingen illustrates a second way by which Stuyvesant, like other magistrates across the United Provinces, summoned a species of isolation. This ruling was intended to be the opposite of the more punitive measures taken against nonconformists. The fatherland had made a distinction between the public and private exercise of worship. Public worship would be clothed in orthodoxy: it would be Reformed. Heterodoxy—the forms of worship of other believers—would be allowed but kept out of sight.45 Stuyvesant and his council promulgated a version of this principle in February 1656. They forbade all public and private conventicles. They stressed that the “Reformed divine service” was rightfully public on legal grounds. They also assumed a right to make judgments we would take as impertinently inappropriate, that is, on theological grounds. Their judgment here was that the Reformed church was “not only lawful but scripturally founded and ordained.”46 This assumption was consistent with a judgment by Stuyvesant seven years later. He would approve local laws, provided they were found to “Concure with the Holy Scripture.”47 Outside the Reformed services, private

18

Chapter 1

reading of scripture and practice of family prayer and worship in an individual’s household according to his or her conscience was to be protected by law. But it must be carried out safely out of sight, hidden away. On this matter, Jaap Jacobs is explicit and, I think, correct. Stuyvesant did not offend against freedom of conscience, but he was obliged to act against public insubordination and its possible consequences.48 In 1663, the West India Company (for its own pragmatic reasons) offered Stuyvesant a third way of dealing with unruly nonconformists: “shut your eyes.”49 Shutting his eyes had not been Stuyvesant’s policy. Yet he too adjusted his decisions regarding toleration to circumstances and reason. He was, for example, reported to have expressed relief that the Quakers’ vessel would not be requesting permission to land at New Amsterdam, and to have acted throughout with moderation “both in words and actions.” He followed an official’s advice to have a nonconformist whipped for unlicensed preaching, but backed away, citing “compassion.” In the matter of an illegal conventicle, he lessened one defendant’s sentence but imposed the force of the law on an officer who had allowed public disobedience to an official ordinance.50 These were not manifestations of indecisiveness or religious irenicism on Stuyvesant’s part. On one level, they were enactments of a conviction expressed in 1663. “Common sense, wisdom . . . [and] carefulness” were, he wrote, essential elements of good government. But so was “piety.” Each element would sustain the others.51 On another level, they testify to the uncertain process of defining and putting in place an uneasy ecclesiastical heterogeneity within one magistrate’s limited jurisdiction. That is, we find Stuyvesant trying to establish workable power structures within the ecclesiastical and juridical order called into being by the Reformation.52 Within this order, one might exercise individual conscience but, as Michel de Certeau has pointed out, not “the individualization of beliefs.”53 Stuyvesant’s words about good government were written in 1663. Although New Netherland had been and was still under threat from natives and the English, relations between Stuyvesant and the merchant community of Manhattan Island were largely harmonious. This was not the case between 1647 and 1653, the years we must now consider. In fact, it may be said that never again was the strident acrimony and the production of destabilizing discourse as extensive as in these years of conflict between Stuyvesant and some among the New Amsterdam merchant community. Never again would we get the intensity and public utilization of such a variety of tropes, genres, and rhetorics. Nor would we have as energized, contradictory, and negative a portrait of Stuyvesant as we do from these years.

Magistracy and Confessional Politics 19

It is possible to envisage an arc joining these early years to those after the surrender of New Netherland when Stuyvesant had to gather his papers and travel to Holland to defend his administration. In both instances, he was made a spectacle of humiliation and rejection. In the first, he was publicly at the vortex of merchants’ criticism textualized in mockery, exaggeration, street language, contempt, and treachery. The same criticisms were dramatized in such theater as merchants carrying their case against him and the company to The Hague; Stuyvesant recalled from New Netherland (and that recall rescinded); Stuyvesant’s traveling with a security guard after his life was threatened; a minister denouncing Stuyvesant from the pulpit; and merchants maneuvering to exercise free trade against the company’s enforced monopolistic restrictions.54 From 1664 through 1667, Stuyvesant was again a spectacle. Privately, he was a spectacle to himself as he prepared his defense, procuring witnesses’ depositions, correspondence, and provincial records. Publicly, he lived out the humiliation of the defeated leader: worse than defeated, one who had surrendered.

Chapter 2

Conflicts and Reputation

Arriving at Manhattan Island, Stuyvesant found a merchant clique determined to remove the West India Company from control of New Netherland and replace it with direct governance under the States General. This was nothing new. Nor was it surprising. Everyone on the island knew that the company’s rule had been an egregious example of greed, negligence, and misdirection resulting in disaster. In 1649, one merchant spoke for all: Stuyvesant’s administration “lies completely prostrate.”1 Cornelis Ch. Goslinga, in the course of his studies of Dutch-Caribbean affairs, has offered an explanation for the company’s failure there and, indirectly, illuminates its similar prostration on Manhattan Island. He defines the trading company as in need of making profits and, simultaneously, operating as an officially governing institution required “to master the techniques of good government.” These tasks, he concludes, “were mutually incompatible.” The company’s solution was “the rigid application of certain monopolistic rights.” But it was a policy that failed to work in the face of local merchants’ demands for free trade. The company, therefore, failed in both aims. Goslinga’s conclusion is especially pertinent. Throughout the years of the company’s existence, he writes, “this conflict between the merchants and the Company government undermined a relation of harmonious cooperation and put distrust, jealousy, latent and open opposition in its place.”2 When Stuyvesant began his administration, then, he was a young director general squeezed between an opposition that wanted complete structural change and a company that knew its existence in New Netherland was on the line.3 Much of the conflict was fought out in words. Contesting parties and ordinary people blamed “words” for the morass they were in.4 The texts in which these words were meant to score points have been subjected to many analyses. They have been read for their ethnographic, psychological,

Conflicts and Reputation 21

and political meanings. They have elicited fascination and been treated masterfully by a number of New Netherland’s foremost historians.5 At the same time, they have thwarted the efforts of those searching for clear motivations. Inadequate contexts have denied certainty about which party’s accusations were the most sound.6 My intention here is not to engage in another explication de texte. It is crucial, however, to consider the repercussions of the contests on Stuyvesant’s immediate and long-term reputation. As I have suggested, Stuyvesant was placed in an almost impossible position in early New Netherland—“almost,” because over the next decade (about 1654–1664), a viable political order did work itself out. He was wrong-footed from the start and forced to be on the defensive. He was brushed with the faults of his predecessor, Willem Kieft, but (as his defamers conceded) was in no position to admit that publicly.7 He was a very different man from Kieft. He had no family connections that would support his acting the aristocrat (as Kieft did), no reason to consider himself superior to commoners. Stuyvesant’s father was a Reformed minister—and filled that role at a time when clergy were not held to be among the upper classes. Kieft had the achievements of family members to call on, giving him reason to think he could “leave behind him a great name,” as his enemies charged.8 There were no grounds for this in Stuyvesant’s case. Yet in the major writings of the time, his reputation is linked closely with Kieft’s, doubling the condemnation and bitterness. From the testimony of the documents we have, Stuyvesant failed to put up a convincing response. He seemed incapable of fighting off the merchants’ accusations of leading a corrupt government—after all, even ordinary citizens expected corruption of one kind or another in a place so distant from home.9 Nor could he shake off the charge of being a tyrant, though, being a Netherlander, he would have been bred on a discourse that excoriated tyranny as a distorted form of government imposed on the Netherlands for decades by the Spanish Hapsburgs.10 He undertook building projects immediately, first the church, then a wharf. But these earned him criticism since they were allegedly company buildings and not public works. He set about restoring the fort at New Amsterdam. But opponents charged that, since “all authority proceeds” from it, the fort was a site of danger and not protection.11 These examples could be multiplied many times over. Stuyvesant’s response to the accusations and obstructionism was of two kinds. First, he turned to the reconciling politics Willem Frijhoff has cited as

22

Chapter 2

characteristic of the Netherlands’ unique approach to power.12 He made conciliatory gestures toward opponents who called themselves Remonstrants— though without the explicitly religious meaning connoted by that term in the Netherlands. Adriaen vander Donck and other merchants were directly involved in resisting his administration and threatening to bring a detailed complaint to Holland.13 By way of conciliation, Stuyvesant offered, for example, to reinstate vander Donck and others of the Nine Men, the quasi-legal or honorary representatives of the city. He would join them in remonstrating to the company about some of its demands on the commonalty. When he was rebuffed, he did not hesitate to abandon negotiative measures for retaliatory policies.14 He refused to call an assembly of the leading merchants in 1649, cited two citizens as traitors and sent them to Holland for judgment (he lost the case), and foolishly confirmed his opponents’ already implacable conviction that politics under the company would continue to be rigidly exclusionary and to that degree unjust.15 Second, Stuyvesant went ahead with projects and policies that advanced the recovery of Manhattan Island and looked to the protection and development of the province. Some comment about these projects is important because it allows us to see that, however crucial the clash of merchants and the company, the wrangling can divert attention from the realities of the daily interactions and occupational tasks of the settlers: all the seemingly trivial performances that contributed to the subtle shift in identity as trading centers such as New Amsterdam and Beverwijck moved away from being voyaging communities to those of settled populations. By overly attending to the confrontation, we run the risk of entering, as it were, a law court with its kind of discourse and adversarial procedures and its calling of learned witnesses (ancient, contemporary, ecclesiastical, profane). We overly attend to its particular kind of point-scoring and studied performances while outside, all around, the laborious (and usually undocumented) construction of a way of life is going on. And so it did go on. Stuyvesant and his council brought down legislation against smugglers, naming names of leading merchants and closing down the coastal havens south of Manhattan Island regularly used by outlaw groups and individuals. They punished company soldiers for selling their firearms to natives and colonists alike. Stuyvesant was also working for a permanent border settlement with New England and, in anticipation of that, looking for ways to populate Long Island. Against the company’s advice, he approved the villages of Hempstead and Flushing as well as the purchase of large tracts

Conflicts and Reputation 23