Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema 8170461782, 9788170461784

Since his untimely death, Ghatak has become a cult figure for followers of serious Indian cinema, the 'enfant terri

864 193 28MB

English Pages 172 [196] Year 2000

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

( I

Aft 0298735 Code l-E-99953666

15 UNIYERSilY Of "ICHIGAN

UNIVERSITY

r FM

AN

Ritwik.Ghatak

Rows and Rows

of Fences

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

ROWS AND ROWS

OF FENCES

Ritwik qh.atak on Cinema

CALCUITA 2000

,,,,,,,,,,, Google

Ongm31from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

PN }qq~, ~ . q l/ ?-

A3

C Seagull Books, Calcutta Cinema and I, an earlier publication, was first published in 1987 by the Ritwik Memorial Trust. The current volume incorporates the material from this earlier publication, along with additional matter. All materials in this volume have been provided by the Ritwik Memorial TrusL

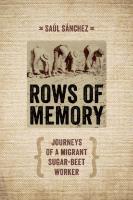

Cover design by Naveen Kishore, using a still from Ghatak's Meghey Dhaka Tara

ISBN 81 7046 178 2

Published by Navem /whore, Seagull &oles Private Limited · 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700 017, India Printed in India by A. Dasgupta at Sun Lithographing Co. 18, Hem Chandra Nailcar Road, C,alcutta 700 010, India

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Contents ••

Preface Foreword

vu

My Coming into Cinema Film and I An Attitude to Life and an Attitude to Art What Ails Indian Filmmaking Music in Indian Cinema and the Epic Approach Bengali Cinema: literary Influence Experimental Cinema Experimental Cinema and I Cinema and the Subjective Factor Some Thoughts on Ajantrilc Filmmaking Rows and Rows of Fences My Films . Film I Want to Make on Vietnam Two Aspects of Cinema Sound in Cinema Interviews Nazarin. On Film Reviews: A Letter to the Editor A Scenario Documentary: The Most Exciting Form of Cinema

1 3 9 16 21

•

IX

The

24 29 33 35 38

41 44

49 53 57

74 80 97 100 102

104

Appendix About the Oraons of Chhotanagpur A Biographical Profile Ftlmography Select Bibliography

Digitized by

Google

119 130

134 171

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

PREFACE The Ritwik Memorial Trust was formed in 1982, with the aim of preserving and disseminating the works of Ritwik Ghat.alt in the several forms in which he had worked. When the original trustees-Satyajit Ray, Bagishwar jha, Surama Ghat.alt, Sankha Ghosh, and Ritaban Ghatak-took up the project, they discovered that the negatives of all his films and most of his writing had been uncared for, and bore the inevitable signs of decay. As a matter of priority the Trust undertook then to restore his films. Over the years since then, with support from various individuaJs, both in the country and abroad, the Trust has succeeded in restoring the majority of his films, including the surviving fragments of some of his unfinished works. The Trust has restored six of his feature films, using the facilities available at some of Europe's finest labo ratories. The new prints have been released in France, th� Netherlands and Switzerland, and featured in screenings at inter national film festivaJs in Europe, America, and elsewhere in Asia. Ftlm society audiences have had the opportunity of taking a fresh look at Ghatak's works. The Trust has played its role in and con tributed to the global 'rediscovery' of Ritwik Ghatak as a master. . As storywriter, essayist, radical polemicist, Ghat.alt was a pro lific writer. The Trust has collected and sorted out a substantial body of his manuscripts and published writings, many of them appearing in little magazines, now defuncL The Trust proposes to publish the complete literary works of Ghatak, with neces.cary introductions and annotations. A beginning was made with Cinema and I (1987) in English, and a selection of his short stories in Bengali (1987), with illustrations by some of Bengal's major artists as their tribute to Ghatak. Both the volumes have gone out ofprinL The present volume includes several new items discovered after Cinema and I had appeared, including a letter to the editor and a selection of Bengali essays on cinema in translation; a con siderably expanded biographical section; and a more authenticat ed filmography. Two of the texts included in the main body of this work are supplemented-in the appendices with translations of

Digitized by

Google

•

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

viii

I

PREF A

cE

texts on the same theme, or may be variations, written in Bengali. In a life of bitter struggle, Ghatak himself did little in the way of preserving or organizing his materials. He was responsible for the selection of the pieces for his first ever book of essays in Bengali, ChalachchitTa, Manush Ebang Aro /(jchhu, published posthumously in February 1976. It remains extremely difficult for a scholar today to put all of his writings in order and draw a clear biographical-chronological narrative out of them. Dates and details often remain elusive , and one can only hope that the Trust will be able some day to put it all together, with the .wistance and cooperation of its wellwishers and admirers of Ghatak. The Trust counts on all those who value Ghatak's life's work as a heritage to be cherished.

Surama GhataJc . Ri(aban GhataJc

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

FOREWORD TO aNEMA AND I In a career that spanned over twenty-five years until his death in 1976 at the age of fifty, Ritwik Ghatak left behind him eight feature film~ and a handful of unfinished fragment.a. Not a large output if one considen him only as a filmmaker. But Ritwik was much more than just that. He was a film teacher, doing a stint .1:5 the viceprincipal of the Film Institute at Punc; he was a playwright and producer, identifying himself with the IDdian People's Thcattc movement; he was also a writer of short stories, claiming that he wrote over fifty which were published, the earliest ones being written when he was barely out of his teens. Of these, a dozen have been unearthed; the rest lie buried in the pages of obscure literary journals, many of which arc probably defunct. What has come as a surprise is the extent to which Ritwik wrote about the cinema. His Bengali articles number well over fifty and cover every possible aspect of the cinema. The present volume brings together his writings on the same subject in English. Ritwik had the misfortune to be largely ignored by the Bengali film public in his lifetime. Only one of his films, Meghe Dhaka Taro (Cloud-capped Star) had been well received. The rest had brief runs, and a generally lukewarm reception from professional film critics. This is particularly unfortunate, since Ritwik was one of the few ttuly original talent.a in the cinema this countty has produced. Nearly all his films are ·marked by an intensity of feeling coupled with an imaginative grasp of the technique of filmmaking. As a creator of powerful images in an epic style he was virtually unsurpassed in Indian cinema. He also had full command over the allimportant aspect of editing; long passages abound in his films which are sttikingly original in the way they are put together. This is all the more remarkable when one doesn't notice any influence of other schools of filmmaking on his work. For him Hollywood might not have existed at all. The occasional echo of classical Soviet cinema is there, but this does not prevent him from being in a class by himself. Ritwik's writings in English on the cinema relate to most aspects of his work. Some deal with his perso~al attitude to film-

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

XI

FOREWORD

making; some to the state of the cinema in the country; othen are concerned with various aspects of film technique; yet others with his own individual films. When writing about his own works, one gets the impression that Ritwik was anxious to explicate them to his audience. One feels the artist's anxiety riot to be misunderstood. He lays partic1dar stress on aspects which are not obvious on the surface: such ~ what he derived from an early study ofJungthe use of the archetype, the Mother image, and even the concept of rebirth. Thematically, Ritwik's lifelong obsession was with the tragedy of Partition. He himself hailed from what was once East Bengal where he had deep roots. It is rarely that a director dwells so singlemindcdly on the same theme. It only serves to underline the depth of his feeling for the subject I hope this book, which in its totality gives a remarkably coherent self-portrait of the filmmaker, will serve to heighten interest in his films which, after all, are the repository of all that he believed in as an artist and as a human being.

Satyajit Ray [Foreword to the first edition of Cinema and I, published in January 1987.)

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

My Coming into Films

Initially, I was a writer. I have written about a hundred shon stories and two novels since the beginning of my career, from way back in 1943. I ha".e always been perturbed seeing the situation around me of the then Bengal. I then felt that though literature is a terrific medium, it woru· slowly into the minds of the people. Somehow, I felt, there is an inadequacy in the medium. To start with, it is remote, and at the same time, limited to a very small readership, serious literature being what it is. Then came a revolution in our Bengal of that time. Came a new wave of dramatic literature led by Shri Bijan Bhattacharya of Nabanna fame. It revolutionized our way of thinking. I found that this was a much more potent medium than literature and also : . most immediate. So I started writing plays, acted in them, directed them and did all the other incidental things around a show. I became closely associated with the Indian People's Theatre Association, in a nutshell, IPTA · Our colleagues and I roam~d extensively all over the place and tried to rouse our people against the ills eating at the vitals of our society. I have played and acted before an audience of ten tho11sand persons also. But I found this was also an inadequate medium. Then I realized that to say your say today, film is the only medium. It can reach millions of people at one go, which no other medium is capable of. Then I came into films. My coming to filins has nothing to do with making money. Rather, it is out of a need .to express my

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

2

Ritwik Ghatalc

pangs and agonies about my suffering people. That is why I have come to cinema. I do not believe in 'entertainment' as they say it or slogan-mongering. Rather, I believe in thinking deeply of the universe, the world at large, the international situation, my · country and finally my own people. I inake films for them. I may be a failure. That is for the people to judge. . · Because all art work involves two parties. One is the giver, the other is the taker. In the case of cinema, when an audience starts seeing a film, they also create. I do not know whether it will be intelligible within this little span of an article. But I know it for certain. A filmmaker throws up certain ideas; it is the audience who fulfils them. Then only does it become a total whole. Filmgoing is a kind of ritual. When the lights go out, the .screen takes over. Then the audience increasingly becomes one. It is a community feeling, one can compare it with going to a church or a masjid or a temple. If a filmmaker can create that kind of mentality in his audience, he is great~such as Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Bunuel, Mizoguchi, Ozu, Fellini, Satyajit Ray, Cacoyannis, Kozintsev, John Ford and others . . I do not know whether I belong to their category, but I try. Originally published in Film Forum, 17-20July 1967.

;

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Film and I

I am coming to &mbay. Fortunatdy, m, mtry into Hindi films is tlan,ugla the kind e/forts of a progressive g,wp of film tntlawiasts who mean business and wilJa whom I w eye to eye about naaturs of an. They have the mJUisite badcground to maAe our joint vmtu,r a significant one. I am really thrilled, the prospects are exciting. Wit/a the ample facilities, technical and othm.uise, that filmn,alcing in Bombay offers, one can rraJI:, have a go at it.

Pitfalls arr t/am. But let us hope we shall find ways to gd around them and amve wit/a h:ealllay, clean, wholesmM and dramatically gripping film/arr. At least, I am fervently hoping so. It is a turning point wilJa me, you A:now. Such a situation naturally leaves one vaguely searching. One lilres to formulate what one means IJ,y one's filmmalcing activities. One tries to take stodc. I am doing the same. I 'WOUid liA:e to formulate my ideas about film. Hmgoes. Film is, basically, a matter of personal statemenL All arts are, in the final analysis. And film seems to be an art. Only, film is a collective arL It needs varied and numerous talents. It does not follow that film is not personal. It may be, at one end, the case of a collective personality, and at the other, may bear the stamp of one individual's temperament upon all the others' creative • • • activities. To be art, either one or the other must be the case. Any work

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

4

lutwilc Ghatalc

that lacks style and viewpoint necessarily lacks personality and thereby ceases to be art. To my mind, this is the very root of the matter. Some hodgepodge thrown together, stylistically divergent images stnmg together by the device of intrigu~ and 'story matter', may be a good evening's entertainment, but no sir, it is not art: Such products abound all around us. One should resign oneself to these sad facts of life. Sometimes one may get great pleasure out of them, but not artistic pleasure. That is why even a considerable artist such as John Ford becomes considerable only at intervals. The rest of present-5ided thesis. His fundamental assessment of present-day reality is a partial and partisan assessment. It does not want to, or is not able to, encompass the whole of reality prevailing today. His sense of doom and hopelessness has made him despair. He wants to go back to fleeting moments of tranquillity and peace. All his almost poetic instances, which abound in the book, talk of peace, freedom from care and worry and the feeling of being lost. This would be understandable if Dr Kracauer were a filmmaker. It would have been an admirable temperament, but these are his private worries which he has tended to impose upon all of us as a theorist. Perhaps all theories of this nature are bound to be so. One's own shortcomings, one's own surroundings are bound to condition one's judgement. Perhaps one should not theorize. Perhaps one should be aware of limitations that are imposed on one. That is why Dr Kracauer is much more successful in the first part of the book than in the latter. Sometimes, one writes a book which bristles with quotations and instances, but which does not achieve much more than an air of pomposity. A previously unpubluhed mnew of Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: Redemption of Physical Reality, Nn.v Yonl- Oxfngwinded words about big ideals and any recent national calamity, grafting this so-called purposeful talk on to age-old formula films. I mean the awarenea, the sense of reaction of a truthful artist to the small things of life-literature today has abandoned th.is approach completely, and seems to have no intention of resuming iL Our cinema is toeing the line. From the foregoing let it not be thought that I reject out of hand all films and all literature being turned out today. There are happy instances, even today, of truthful films based on novels, and our literature is not all dead. But it is a question of proportion, to my mind. And that proportion is becoming alarming to me. Although the influence of literature on cinema brings many positive gains, these gains are being neutralized by other factor-s not so desirable. It may be true that, considering that state of filmmaking in other parts of India, Bengali cinema presents coherent, consistent and logical fare, but that is not enough. Moreover, I consider cinema to be something international and, in that context, these shortcomings loom very large. We have to catch up with the best of world cinema. . . There are heart-warming and welcome signs all round in Bengal. Large sections of Bengali audiences are sitting up and taking notice. They are being aroused. They are clamouring for the ptesentation of reality in cinema. Scores of film societies are springing up all over. They are organizing audience thinking and reaction, educating the intelligentsia in film appreciation. · Seeing this rapid growth, I am reminded of things as they were many years ago. College students liked to join a literary

• Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

-

_,._.. . .: ,

28

lutwiJcGhatalc

circle and become poets. Today they join a film society. Because, in Bengal, cinema has become the vanguard of culture in place of literature. The youth, the student, the whitecollar worker-they are all yearning for true cinema, committed cinema, pure cinema, from our filmmakers. They want no more of those re-hashed stories and novels which speak of days gone by. They deserve it! Originally publish«!. in Filmfare, 1965.

•

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

&periment:al Cinema

The word 'experiment' with reference to fihmpaking has become almost a clichc. Experimentation in cinema is a vast and tricky subject. Experimental films are also called, at times, 'art films'. Experiment in any medium is the extension of the potentialities of the medium itself. Experimental films are explorations in the cinema, by people who seek self~xpression in art. Each of these pictures is a personal expression of the artist and it is invariably the product of a single mind. Experimentation in cinema can be of two types: ( 1) Experimentation with the medium itself. ( ii) Experimentation with the medium for other purposes.

I

&pt, ifflffllation with tM m«liu,n itself This son of experimentation can be classified into two groups: (1) Mechanical-technical and ( ii) Artistic.

Mechanical-technical. You must be knowing that the National Film Board of Canada has an artist called Norman MacLaren. He continually experiments with the medium itself~ He goes to the extent of creating sound by scratching the soundtrack. Sound, you know, can be of two types, (a) varial>le area and (b) variable density. The former has been used till now. McLaren scratches the soundtrack and produces peculiar sounds which cannot be produced in the normal way. He has been eminently successful in his experimentation. This is experimentation in the mechanical

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

--

30

Ritwilc Ghatak

sense. Similarly, all the wide-screen systems you have been hearing about o_f late, like Cinemascope, Todd-AO and Cinerama-all these are the results of experimentation in the mechanical field. Abel Gance, way back in 1928, used the triple !!(:Teen systems for his picture Napoleon. The anamorphic lens is the basis of all wide--screen systems. Ultimately the developments have culminated in Cinerama and 'total screen'. This is experimental in mechanical-technical terms. Artistic. When we talk of 'experimental films', we mean artistic experiment, which is a tricky proposition. It .can be experimentation with lines, circles etc. Psychologists have proved that such kinds of experimentation have a tremendous impact on . . audience minds. If an artist tries to experiment with lines only, to create certain emotional moods, then his experimentation comes under the. 'artistic' category. The same applies to anyone who wants to experiment with colour--colour has so many facets for creating emotional moods. The same is also true of music (not songs), which is the most abstract of all arts. Certain moods which you ·cannot express through lines or colour can be created through music. Let me recall in this connection Walt Disney's Malce Mine Music, which is really experimental in the sense that it is a collection of musical theme.s on 900 to 1000 ft. length of films, and also his Fantasia, which is an exploration into the abstract aspect of 'music'. Although Walt Disney has crudely commercialized his innovations, they are very seriously done. This sort of abstract approach to the medium can be truly called experimental. It is really a joy to try to invoke certain moods through abstract types of experimentation. . Then there is the surrealistic approach, the school headed by Salvador Dali and others-Luis Buiiuel was a surrealist in his early film, L '.Age d 'Or ['Age of Gold']. This approach calls for the abstraction of re.ality for its essentials, as the artist thinks fit. In Bunuel's othc;r film Un chim andalou, in the rape sequence we se·e abstract images in quick succession, such as the scratching of an eyeball, dripping blood, a huge piano, two dead donkeys on the piano ... etc. This is one kind of experiment. I am oversimplifying the facts of experimental cinema. Whatever be the experiments, all of them are trying to find the limit, the end, the border, up to which the expression of film can go. This is the basic approach of all experimental cinema. It is the concern of

Digitized by

Google

Origi,nal from •

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Experimental Cinnna

31

artists like Buftuel, Fellini, Eisenstein, Pudovkin-their concern for man has given a lead to experimentation in the cinema. They throw men into a situation and probe deep to find how much they can realize. Their deep concern for humanity, for man and his society, is the primary r~ason for their creative activities in the experimental field. La Dolce Vita is an experimentation in the sense that it has summed up the whole 2000 years of European civilization, which is decaying and dying, within the framework of a motion picture of three hours' duration. Fellini took up a form of a peculiar type-a structure of filmmaking never before tried by anybody-a structure full of symbols. From ~e filth and dirt of Roman high life and lower life to the absolutely frigid sexy film star all these are summed up in a sea-monster writhing and dying. His hatred for his surroundings and the pus generated within modern society has been summed up in this symbol. Dr Steiner says he .is afraid of the times in which he is living, and later, when he commits suicide after killing his two children, the police inspector asks the hero Mastroianni, who happens to know him, me reason. Mastroianni says: 'He was afraid, afraid of the present world.' These are gems, words which carry more meaning than a volume of sentences. Eisenstein experiments when he uses the intellectual montage in October. Flaherty experiments when he puts the lone cajun boy in the path of the onslaught of industrialization in peaceful bayou country. In my own Ajantrilc, I have tried to experiment with a strange love between man and machine. These are all ·attempts at experimentation. Eisenstein's compositions and takes in &ttleship Potemkin were experimental in their time, but not any longer. Experiment is an ever-living and never dying thing. 'How can I do something new . ·. .' should be the attitude of anyone wanting to make experimental films. Experimenters always have to be alert. In Alain Resnais' Last Year at Marienbad, for which Alain Robbe-Grillet wrote the script, we are never introduced to the characters. Resnais has tried tQ walk backwards and forwards in time, just as in a dream. His justification is that, while you experience a dream, you do not find anything illogical. You are wholly immersed in it. In an inteiview, Robbe-Grillet stated that · this is an attempt to catch the dreamlike quality of. the film.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

RitwiJc GhataJc

32

French artists have a reason for experimentation. 2

&.1-e• un,11latioa with 11N . . . . .for od,o-,,,,,,,_ You can experiment with the film medium to explore the outside world. Just like in that fine documentary on the Todas, The Vanishing Tribe. Tribals like the Onges of the Andamans and the Anganagas of Nagaland arc a little stream in the development of Indian life and culture. Films made on their mode of life, customs, festivals, gods, have a wide anthropological and cultural interest. These films can definitely be called experimental, because their makers take their cameras to remote comers of the world and endure heavy odds trying to record their experiences as they find them . . . Ta/Jc giwn at the Film and Television Training Institute, Pune, 16 &f,lnnber 1964.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

&perimental Cinema and I

In India, there has not been much experiment in film. The few which have been made have mostly been in Bengali. There have been some stray attempts in other provinces, like the latest one by M. F. H11sain about an artist's approach to the world. But all this falls into that ambiguous territory called 'Documentary'. It is only in Bengal that some feature films have been attempted which may go by the name of 'experimental'. I am not competent to speak about other people's work, so I refrain from commenting on them. I can only speak of my little experience. My first film, Ajantrilc., is normally called an experimental film. I don't know how far that is true. But I have been asked from different quarters for whom am I making this film. I always answer that I am making it for myself and for nobody else. This does not mean, to sympathetic people I say, that I have a narciuistic approach to art. And films seem to be art. You must be engaged to society. You must commit yourself t~ be for good, against evil, in man's destiny. I don't mean like Roger Vadim, who is interested in Napoleon's life because he wants to show the contour of Napoleon's couch, where he used to enjoy women, and not his historical role . . . the same goes for my opinion of people like Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet-they represent the decadent forces in Western civilization. I consider them completely invalid as experimentalists. For instance, I have had the doubtful pleasure of seeing Hiroshima mon amour and L'annk dern~ ti Mmienbad. These films seem to me completely hollow, gimmicky, ·and posed. I refuse to take them to be real experiments in the b1le sense of the term.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Ritwik Ghata/c

34

This brings up the question: what is experiment? Herc lies the crux. As we all know, everything in this universe is relative. Experiment in films, in relation to what? In relation to man and his society. Experiment cannot dangle in a void. It must belong. Belong to man. I have seen some films by Western filmmakers like Fellini, whom Gerasimov condemned in Cannes as working out a drain inspector's report in his film La Dolce Vita, but Fellini has portrayed most boldly and most sincerely the life around him as we saw it. It is a death certificate to Western civilization. In my films, I have tried to portray my country and the sorrows and sufferings of my people to the best of my ability. Whatever I might have achieved, there was no dearth of sincerity. But sincerity alone cannot amble very far. My ability limits me, and I can operate within that limitation. In my humble opinion, Komal Gandhar probably tried to break the shackles that strait:jacket our cinema. It has a pattern and an approach which may be tentatively called 'experimental'. Subamardcha. Here is a film in which I tried to deal a straight knock-out blow to the nose. It pulls no punches. It has been called melodramatic, and probably rightly so. But critics should remember the name of a gentleman called Benoit Brecht; who dealt with coincidences and who developed a thing called the 'alienation effect'. His epic approach to things has influenced me a lot. I have tried in my little way to work out, with the tools of my profession, some similar works: To me, this is experiment. It may be justifiably said that it is not. I have no quarrel to pick with such , opinions. And I end this small essay with a little quotation from Tagore. Tagore somewhere said that all art must be primarily truthful and only then beautiful. Truth does not make any work a piece of art, but without truth there is no art worth its salt. We'd better remember this.

. Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Cinema•and the Subjecti.ve Factor

The symbolic-imaginative view of the world is just as organic a part of a child's life as the view transmitted by the sense-organs. It represents the natural and spontaneous striving which adds to man's biological bond a parallel and equivalent psychic bond, thus enriching life by another dimension-and it is eminently thi.~ dimension that male.es man what he is. It is the root of all creativity. C. G.Jung, The Colkctive Unconscious The two fundamental types of mind are complementary: the tough-minded, representing the inert, reactionary; and the tender-minded, the living progressive impulse, respectively; attachment to the local and timely and the impulse to the timeless universal. In human history the two have faced each other in dialogue since the beginning, and the effect has been that actual progress and process from lesser to greater horizons, simple to complex organizations, slight to rich patf.C:ms of art work which is civilization in its flowering in time ... there is a deep psychological cleavage separating the tough-minded 'honest hunters' from tender-minded 'shamans'. Joseph C~pbell, The Maslcs of God: Primitive Mythol.ogy

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

36

Ritwik Ghatalc The etymological relations between seizure, fury, passion, spirit, song, ardour, being-outside-oneself, poetry and oracle characterize the creative aspect of the Unconscious, whose activity sets a man in motion, overpowers him and makes him its instrument. The superiority of the irrupting powers of the Unconscious, when they appear spontaneously, more or less excludes the ego and consciousness; that is to say, men are _seized and possessed by these powers. But since this possession causes higher, supra-conscious powers to appear in man, it is sought after in cult, ritual and art. Erich Neumann, The Grtat Mother

I apologize for starting off in such a manner-with a barrage of quotations. But, unfortunately, these are essential for establishing the point that I am going to make. And there may be some consolation in the thought that we have got rid of them once for all. Whenever one has to think of the subjective aspect in cint~ma one has to trace it through all the arts; nay, through civilizat ·,n itself, and through the very roots of all creative impulses. 1·he matter cannot be taken up in isolation. Since Depth Psychology and Comparative Mythology have laid bare certain fundamental workings of the human psyche as everrecurring constellations of primordial archetypes, our task today has become easier. We now know, all that creates art in the human psyche also creates religion; a medicine man, a 'shaman', a 'rishi', a 'poet', and a 'village woman possessed by a seizure' are, fundamentally, set in motion by the same or similar kinds of unconscious forces .. . And these forces are the very ones which are continually nourishing the subjective psychic bond, giving an inner subjective correspondence to the objective creation around us. It follows that all art is subjective. Any work of art is the artist's subjective approximation of the reality around him. It is a sort of reaction set in motion by the creative impulse of the human • unconscious. The entire history of human civilization shows a peculiar phenomenon. As William James has termed them-there are

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Cinema and the Subjective Factor

37

always two types of minds operating through the length and breadth of human history: the 'tough' and the 'tender-minded'. The tough-minded are always the 'honest hunters'. It does not matter whether they hunt for mammoths, dollars, pelts or working hypotheses. The tender-minded ones are the 'shamans', the rishis and the poets, the seers and the singers, the possessed and the inspired of this world. It is the second kind of men who are eminently the vessels or vehicles of that force of the unconscious through whom and whose creations become manifest the images and symbols of that dark deep. Objectivization of this essentially subjective element is the task allotted to such men. And thus the dialectics is born: the interplay of the subjective and the objective. As civilization progresses, Prometheus becomes Aeschylus. From here branch off many theories. Sometimes there is no theory, but practice. What would you call Gorky's works, for instance? I personally would like to call them 'Essential Realism'. In what category could fall Fellini's La Dolu Vita? I do not know. That sea-monster topples all logic! In fact, I have neither the space nor the inclination for going into all the schools and theories of subjectivism. I find the subjective wherever the exaltation is, whatever the inspiration is, on this level. All art, in the last analysis, is poetry. Poetry is the archetype of all creativity. Cinema at its best turns into poetry. There is a saying in· Comparative Mythology concerning the 'blood revenge' psychology in primitive man. By a strange alchemy in the human psyche, 'All that is killed turns father.' In art, all that is subjective turns poetic. And cinema. sometimes, seems to be an art. Originally published in Chitrakalpa, voL2, no. l, October 1967.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Some Thoughts onAjaotrik

For twelve long years, I had thought about this story before I made it into a film. When it first came my way, accidentally, I was a green boy, newly come to Calcutta and fresh from the university. Ajantrilc caught my imagination and held it for ten days at a stretch-for more reason than the alliteration with my name. I thought about it for a long time in a vague and general sort of way. Never concretely. What struck me most was its philosophical implication. Here was a story which sought to establish a new relationship in our literature the very significant and inevitable relationship between man and machine. Our literature, in fact our culture itself (i.e. the culture of middle-class city-dwellers) has never cared .very much for the machine age. The idea of the machine has always held an association of monstrosity for us. It devours all that is good, all that is contemplative and spiritual. It is something that is alien to the spirit of our culture the spirit of ancient, venerable India. It stands for clash and clangour, for swift,· destructive change, for fermenting discontent. I am not a sociologist. I cannot explain the phenomenon. This apathy may be due to the fact that all change and the very introduction of the machine age was the handiwork of foreign overlords. It might have more comprehensive causes, encompassing all the pangs of Western civilization. But the endproduct of all these causes seems to be an ideological streak which is doing immense harm in all practical spheres of life. This attitude is hardly compatible with the objective truth as it obtains in present-day India. Or in our future, for that matter.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Some Thoughts.on Ajantrilc

39

With all our newly achieved technology, we have yet to find ways of integrating the future into our heritage. The order of the day is an emotional integration with this machine age. And that is precisely what A.jantrilc, the story, has achieved for the first time in our literature. It has achieved it in a unique, and in my opinion, typically Indian way. It contains that quaint indigenous flavour in its plot structure, its characterization, its very style of narration. Also, it rings true. It rings true in every line of it. I have seen such men (I have had the doubtful pleasure of meeting Bimal himself in real life) and have been able to believe in their emotions. There lies the greatest source of power of the story. I had a chance and made the film. It was fun all the way . through-it is still fun while grossing exactly nothing at the boxoffice. There were other points of atuaction for me. FU'Stly, the story is laid in a terrain which is one of the least known to normal Bengali film-goen. They have no emotional attachment with it. Try however I might, I could not peddle in nostalgic sentimentalism, which is the curse of many a fine worker in this country. I had to create new values, all within the span of the film itself. On the other hand I could cash in on the novelty of the landscape. The different planes and levels are rcfieshingly unusual to the plainsmen of the Gangetic delta. Secondly, the tribal people. They are the people who own the land where the story is laid. Without them the landscape would lose its charm and meaning. I cannot manhal my camera on any spot without integrating them into my composition. · Also, it is a silly story. Only silly people can identify themselves with a man who believes that that God-forsaken car has life. Silly people like children, simple folk like pea.cants, animists like tribals. To us city folks, it is a story of a crazy man. Especially the fact that it is a machine. Had it been a bullock or an elephant or some other animal object, it would not have been so difficult. We could imagine ourselves in love with a river or a stone. But a machine there we draw the line. But these people do not have that difficulty. They are constantly in the process of assimilating anything new that comes

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

40

Ruwilc GhataJc

their way. In all our folk art the signs of such assimilation are manifesL This pr~ess is even more marked among the tribal people of Central Ind,a. The tribe I chose-the Oraons are very cultureminded and have this tendency in a pronounced manner. I had a nodding acquaintance with them, having been among them as a documentary filmmaker for about five years. And I wondered again and again at their vigorous imagination. They would fully undentand Bimal, for they themselves are like him. The Oraons have the same attitude to externals which i,s the emotional thesis of this story. I found an affinity between their pathetic ·fallacy and Bimal's. For this reason they provided the ideal setting for this film. I could utilize their many significant customs. The different moods created by their high-flying bairoMis (flags) tilted at different angles and dangled in diff~rent tempos is an expression of the most artistic temperament. I admit that these and many other things were too specialized in their meaning to have any general significance. But if I could go on integrating them into my pattern of things in a consistent manner, I could hope to arrive at a cumulative effect which would be a major contributing factor beyond just local colour. Thirdly, the story has a ramshackle car as its central character. This very fact threw up so many plastic and dynamic potentialities. I could always fall back upon mechanical speed what with opportunities of bringing in the time-honoured mechanism of the chase and hair-breadth escapes and breakdowns at judiciously chosen moments! Fourthly, we had to work with the poorest possible materials and that, too, on a shoe-string budget. This film threw us a challenge at every step. Every shot taken was every shot achieved. This seemed to me to be really invigoratj.ng. It is a situation in which one curses oneself at every step and likes iL All these considerations drove me to Ajantrilc, and I jumped at the first opportunity to make iL Originally publish«!. in Indian Film Review, Deambn- 19.58.

Digitized by

Google

Original from -

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Filmmaking is not an esoteric thing to me. I consider filmmaking-to start with a personal thing. If a person does not have a vision of his own, he cannot create. People say that music is the most abstract of all the arts. Though I am a disciple of one of the greatest -gurus of India Ustad Alauddin Khan-I think that filmmaking can be and is more abstracL I am not going into the df'taih of filmmaking. That is for the audiences to sec. But I can talk of something else which no filmmaker ever talks about. That is the people's co-operation, without which nothing could ever have been made. I can cite certain examples. I think that will help our countrymen to undentand how great our people are. While I was making my latest film, julcti Talclco ar Gappo, ['Arguments and a Story'] I had to go to a village and had to stay there for a few days. _ The persons with whom I had to stay were a poor peasant couple, victims of my exalted didi, Indira Gandhi. I was at that time oozing blood, as I had six cavities in my left lung, that, too, at a very advanced stage of pthysis. Before every shot I would start vomiting blood. This peasant couple looked after me and fed me (though I had enough resources with me). One night I asked the lady (the wife), 'How do you live?' She said, 'Rice, wheat, bafra, bhutta. everything is a dream to us. We have a small plot of land from where we bring some Mindi which we sell in the market ten miles away, and buy a little mustard oil. We cannot buy kerosene. So we cannot afford the luxury of a lamp in our huL' They eat almost poisonous herbs from nearby jungles once a

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

42

RuwiJc Ghatalc

day. The whole night they live in the dark. She said, 'The authorities have not yet been able to steal two things from us, God's air and the sun. But they will.' I am supposed to be a hard-boiled nut, but believe me, tears came to my eyes. Such is the condition of my people, and what kind of films do we make! Then let me tell you about another incident. In I 972 I was making a film in so-called Bangladesh-Titas FJcti Nadir Nam ['A River called Titas']. I was shooting seventy-two miles away from Dhaka town. I had a stint of about fifteen days there. I shot my film both in a Hindu village and fifteen Muslim villages by the side of the river Padma. On the last day of the shoot, the village chief of the Hindu village asked me to ferry across and have lunch with him and his family. When I told my unit members to have their lunch they thought that I was going to a booze party. Because I am well-known as a drunkard. So I drove them away and relished the very simple food that the chiefs wife dished out to me. While I was going back to my launch, I had to pass through the Muslim village where I had also shot the film. The chief there accosted me and said, 'You have to eat with us tomorrow.' I told him that my work there was complete, and I would go back to Dhaka and then to Calcutta. He said, 'Insha Allah agar Khuda ne chaha to tu:mhe saJcnahi padq;a, aur mat sath lt.hana padega.' I smiled. Then I went back to the launch. My cameraman told me, 'Dada, I think there have been some error in the use of filters. If you allow me to take your car to Dhaka, I will proce§ those shots overnight and bring back the re~rt by dawn.' And the long and short of it is that he came back and said that all the shots were NGs. So I had to stay on. Next morning, when I went to the Muslim village to shoot, the chief of that village told me, 'Sala, didn't I tell you yesterday that you would have to eat a meal with me?' I had to sit and eat with that rascal, and he fed me like nobody's business! Then I remember, in 1956, I was making a film A.jantrilc in the deep interior of Ranchi District in Bihar, forty-six miles away from the nearest railway station. I had to shoot a dance sequence with a tribe called the Oraons. They had many peculiar social

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Filmmaking

43

customs. One of them is called Dhumkuria; it is a kind of village club. I had to put up there, though my unit stayed in a nearby forest bungalow. But because I had to be intimate with these people, I had to stay, drink and dance with them every evening. I suddenly became feverish, running up a high temperature. Prasadi, an aboriginal girl, looked after me and nursed me back to health, like a ·mother. Mind you, there was no doctor at all within a thirty or forty mile area. It was deep.in the jungle. I shall never forget that village girl. The memory remains. I wish I could know her whereabouts. I can enumerate incidents like this a hundred times more interesting because I have spent thirty-two years of my blessed life in the bloody game of ~aking. In conclusion, let me I give you a beautiful example of what we city folks are like. Some months back I was in New Delhi, staying at a Bengali guest house which is just off the end of Anand Parbat. Some friends of mine also reside there, in the nearby jungle, who appear to be better than us homo sapims (human . beings). They are golden-haired monkeys.· Every morning some rich fellows used to come in a car with a bunch of bananas and throw the fruits to the monkeys. One day a poor vagabond boy came to one of those fellows and begged for one banana. He was beaten mercilessly and all those bananas went into the stomach of monkeys. Such is life and what films we make! There's no gainsaying it. Originally publish«l, posthumowly, in Chitrabeekshan, vol. 9, nos. 4-7,Janw:ny-April 1976.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Rows and Rows ofFences

You might have been a bit more indulgent towards us if you only knew how many fences we have to cross to make a film. We could begin with our minds. It would be wrong to assume that we arc all ready with a rich storehouse of clear and beautiful ideas. As a matter of fact, we are all busy groping abouL We are yet to sort out all the stuff in our minds, and all the possibilities that lie buried in this medium called film, that we have chosen for ourselves. Moreover, this whole business of filmmaking is such gruelling work that once we get on to the job, a lot of our fantasies seem to slip out of our minds. The· still, quiet setting then gives way to an enormous sacrific~al arena, glowing with heat, with hundreds of workers and hundreds of jobs caught up in a glorious festive dance. Only a small part of the little that had been thought out initially gets realized at the end. All this has to do with one's own incapacity. Imagination will always take a beating like this from reality. But over and above, there is that ceaseless passio~ of ours to feel the pulse of the people and measure how it beats. Our means to measure the pace of the pulse is woefully inadequate. A mistake there takes its inevitable toll: But anxiety and uncertainty over the ultimate impact of the film goes on shaking every bit of self-confidence all the while that the film is being made. It is reflected in the work of art itself and produces a different result. Painful speculation over what people will accept and what they will not can be terribly agonizing, as every sufferer knows for himself. This is one row of fences that comes to mind. Then one can

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Rows and Rows ofFmces

4,

think of criticism. Private criticism or face to face criticism or collective criticism have just properly begun in our country. All the criticism that has some influence appean in the ncwspapcn. The artists in their tum, however, arc not benefited to the extent that they should be. The main reason being that whenever a film is criticized, it is approached in total insulation, divested of its connections with time and people. There is a serious lack of undentanding of pe1spe(tivc, of the background that a work has in its indigenous culture. It is the absence of such an understanding that drives us again and again to sick courses. Behind every film there arc a few men who have done something earlier, and have been showing signs of doing something more in the future. Any attempt to point out to these people the direction they should take would be meaningless unless the critic takes care to point out which virtues and failings visible in their earlier works have been dropped in the present one, and what that indicates. The main point about the film remains unsaid if the critic does not indicate the mainstream against which the film appears and what trend it comes to strengthen. The film under consideration represents a particular wave in the larger current of filmmaking at a given point of time; hence it is the critic's obligation to underline what force the film strengthens in the given political setting of the country. It is also essential to take into account what place the particular film occupies in terms of the achievements in the other arts, for film is now slowly coming to be judged by the parameten of art. The aesthetic and emotional evaluation of a film can be accomplished only when all these aspects are drawn into the orbit .-the concerns of the people of the country, the achievements of this particular .film in terms of several achievements in several other wonderful works of art, and the social value of filmmaking here. It is only an evaluation on these terms that can measure correctly the errors and visions and blindness of the artisL Only if this is achieved will the artist draw lessons from criticism. But that is something that never happens. Criticism only serves to erect a further fence of egotism around the artist, who develops a foolish streak of obstinacy; and plunges him into the game of hurling stones into the darkness. Now take a look at another aspect, that of business. We can make a film only if some people are prepared to shell out some

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

46

Ruwilc GhataJc

cash. And they would naturally like to get their money back with some profit in the bargain. They would naturally invest their money in a proposition -about which they are persuaded that their profits are assured. That is yet another difficult fence to cross. Let us leave the producen ouL For, after all, they are not the real investors. It is the distributors and the exhibitors who constitute that chosen race. There has been a lot of writing about and laughing over what the distributon and exhibiton have had to say, but that has not annihilated them. Their ideas still rule the roost. For they have always called the tune with their money power. Sounds scary. But that's the truth. It does not help at all to ridicule it away. One has to take it in all seriousness. And only once one does that can one build towards a protest strong enough. But the protest has to take recourse to their own arguments to beat them down. As long as that does not seem to be forthcoming, all that we can do is to try to make them understand and try to work with them on the basis of that '!ffldentanding. The only other way left is to stop working. And since that makes no sense at all, we come face to face with the issue of stepping over the fence that this problem represents. And we are left with no option but to follow the ancient principle of wisdom that advised the learned man to give up half of anything rather than lose the whole of it. All the assaults we direct against this system are bound to be futile, for the economy itself sustains iL That can be no excuse, for all excuses are hateful, and there are differences between men. It would be a betrayal of the struggle if the excuse is treated as absolute. And that would be positively nothing short of obscene. Filmmaken like us will be gratified if people just accept the fact that we are fenced in. It often happens that there is a film that could get a fair run with a little bit of enthusiasm and hard work going into promoting it. But an attitude that begins with the assumption that it must be an odd fish, and therefore without prospects, so send it to hell, is enough to send it to the rubbish heap. This is the one line of business where loss is synonymous with not being able to make the highest possible profit, and that, too, immediately. There is no consideration of future prospects in this

"

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Rows and Rows ofFences 47 busineu. Dreamen dreaming of immortal an are total misfits in

this paradise of literalncu. Those who run like race horses in this field live in a state that one does not feel like discussing at all. An account of the arrangements within which these tradesmen of cinema operate would make for a tome that could compete with the best mystery and adventure stories. · Now we can come to you, the spectators. You are the real support of the busineumen. The goat can fight only from the strength that it cao draw from·its support. You get wh~t you like. You don't like the new kind of films. You like a complete work of art like Pather Pandaali, the kind of work that appears only once in an age. Otherwise you go for things that are not worth making. You could never accept A.pamjito. The lou was more youn than the artist's. If the more aware of the spectators cannot arouse the conscience of the common people through setting up film clubs or by any other means whatsoever, then you deserve your Bat-tala and you do not have any right to cry over the fact that there is no Rabindranath Tagore for you any longer. I am totally convinced that the loss is youn. It does not concern the filmmakers, really. They are staking their private lives and family lives alike. But that leaves them with a mad joy, the joy of a passionate meditation. But you are left with very little, and soon there will be nothing for you. And yet it is all in your power. You are all-powerful. You have the final say. Why don't you attack, hit out! But let us live, if you find any reason why we should live. If you do not find a reason, scream it out. Write to the newspapers. Gather a crowd at the nearest street crossing. Shout in your clubs. ·A dead Bengali culture is clinging desperately today to this new medium. Why don't you prove once and for all that you do not want it, and let that be the end of it all! Then we can move on to make the blockbusters with a clear conscience, and sit bare-bodied puffing at our hoo~s. It is time to decide which side you are on. You are a fence younelves, the most ominous, perhaps. Our country has produced the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The philosophy that our peasants carry with them is something rare in the rest of the world. We love our misery. We love our joy, too: But we shall not give you up till we are entirely

Digitized by

Google

. Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

48

RjtwiJc Ghatalc

sure. The world of cinema throbs with the certainty that something will be born. Try to feel our presence. Try to undentand that we are sailing through a flowing river. What we are right now is not our consummation. We shall grow, we shall become large and cast a large shade around us. We are waiting for water. You should have been able by now to recognize that we are professional filmmakers, who have to move within the stern constraints of the trade and have to make commercial films. Shakespeare created a great character called Falstaff. We are his descendants. A critic called John Palmer had something wonderful to say about Falstaff whom he described as 'the most vital expression in literature of man's determination to triumph over the vile body. He is the image of all mankind as a creation of driving intelligence tied to a belly that has to be fed.' To fill our bellies remains the main problem-the problem • that leads to all the degradation, all the sins. And yet the right to fill the belly is one of man's birthrights, which has been denied to him ever since he left behind the phase of primitive communism. He will return to that state again once the communism of the future envelops his life. But spread between those two points of time lies a nightmare of reality. There will be a time when the drudgery of survival that has covered for ever all the good that man is capable of will be suddenly lifted, allowing the will and capacity of mankind the freedom of hydrogen, and then we shall not come whining to you. The memory of primitive communism itself is the guarantee that there will be a time like that again. That was a time when everyone had food. But it needed a lot of labour to create this new world which brought civilization into being and made it possible for man to catapult to the fiery dust of the surface of the moon. There will be a time again when there will be no firing on the streets, and no weeping mothen. And we shall be making films to our hearts' content. For then many of the fences are bound to fall to the dusL Originally published in &ngali as Sari Sari Panchil', in the ptriodical Chalachchitra, 1959. Translated by Sami/c Band-,opadlryay.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

My Films

We were born into a critical age. In our boyhood we have seen a Bengal, whole and glorious. Rabindranath, with his towering genius, was at the height of his literary creativity, while Bengali literature was experiencing a fresh blossoming with the works of the Kallol group, and the national movement had spread wide and deep into schools and colleges and the spirit of the youth. Rural Bengal, still revelling in its fairy ·ta1es, panchalis, and its thirteen festivals in twelve months, throbbed with the hope of a new spurt of life. This was the world that was shattered by the War, the Famine, and when the Congress and the Muslim League brought disaster to the country and tore it into two to snatch for it a fragmented independence. Communal riots engulfed the country. The waters of the Ganga and the Padma flowed crimson with the blood of warring brothers. All this was part of the experience that happened around us. Our dreams faded away. We crashed on our faces, clinging to a crumbling Bengal, divested of all its glory. What a Bengal remained, with poverty and immorality as our daily companions, with blacltmarketeers and dishonest politicians ruling the roost, and men doomed to horror and misery! I have not been able to break loose from this theme in all the that I have made .recently. What I have found most urgent is to present to the public eye the crumbling appearance of a divided Bengal to awaken the Bengalis to an awareness of their state and a concern for their past and the future. As an artist I have tried to remain honest, and it is for the future to decide how far I have succeeded. I began work on Subamare/cha after I had completed Meghey

films

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

•

Ritwilc GhataJc Dhalra Tara and Komal Gandhar. It was not so simple, however, as I 50

put it now. I have known extreme anxiety, hassles, physical debility, after completing every film. It is impossible to explain to an outsider, to one who is not in the business of making films, how intolerably difficult it has become to make experimental films in Bengal. The situation is most critical now, with the cost of filmmaking almost doubled. How can one expect a producer who has invested three to four lakhs of rupees in these days to go on supporting experimental films, if as a businessman, he cannot recover even his investment? In spite of all this, I took on Subarnarelcha after I had completed Komal Gandhar. Let's not get onto the question of all the hurdles that I had to cross to make this film. I would rather recall an episode from when we were shooting. We were camping at the time on the bank of the Subamarekha. I did not have a clear plan of the narrative sequence to be followed in the film in my mind as yet, and was doing outdoor shooting out of sequence. One morning my younger daughter ran up to me to tell me how she had been scared by a Bohurupee who had suddenly appeared before her, while she was walking alone on a mud road in the fields, and had chased her in his horrible guise of Kali. In a flash I could see Seeta, the central character of my film, as a child of today, screaming out in panic, maybe in the same way, as she suddenly confronted Mahalrala. I sought the Bohurupee out. I did not know how exactly I would use him, I had no clear idea as yet; still I carried out the shooting. I do not know how credible it has appeared in the film to the viewers, but for me it has been vitally significant. In the film, I have drawn on this theme of Mahalcala in several ways to underscore the hollow values of modem life rent asunder from its moorings in the pumnic tradition. I have used _the· pumnas in ·the same arbitrary manner in my earlier films too-in Meghey Dhalra Tam and Komal Gandhar, for example. The traditional songs that circulate in Bengal at the time when Uma is supposed to return to her in-laws' home have been used as part of the music in Meghey Dhalca Tara, just as wedding songs are profusely scattered throughout Komal Gandh.ar. I desire a reunion of·the two Bengals. Hence the film is replete with songs of union. When the camera suddenly comes to a halt at the dead end of a railway track, where the old road to

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

MyFilms

51

eastern Bengal has been snapped off, it raises (towards the close of the film) a searing scream in Anasuya's heart. Such a use of Mahalcala offers certain advantages that are associated with th~ use of mythology in art. On the bank of the Subarnarekha I have seen an abandoned aerodrome sprawling over a large area. A little boy and a little girl, fascinated with wonder and lost amidst the ruins of that aerodrome, have gone searching for their forgotten past. The two innocent creatures would not know that it is several such ruins of aerodromes that lie behind the disaster that looms over them. Still they play in the midst of destruction and ruins. How frightening their innocence isl Subarnarelha is not a flawless film. The story chosen was screamingly melodramatic. I have joined the differe~t phases of the narrative, one to another, to make it a story of fateful coincidences. There are several novels that offer parallels for such plotting, e.g. Gora or Naulcadubi or Shesher Kabita, all by Rabindranath, where the author is not concerned exclusively with telling a story but more concerned with attitudes as they evolved with the events. Such coincidences, even if they occasionally appear incredible, would not really jar as long as there is a verisimilitude to it all. The death of Abhiram's mother or Ishwar discovering Seeta in the brothel would not appear incredible if I have succeeded in projecting the problems of Abhiram and Seeta, and Haraprasad and Ishwar authentically. The divided, debilitated Bengal that we have known for days on end is in the same state as Seeta in the brothel. And we who have lived in an undivided Bengal survive in a daze after a night of orgy. There has been such a spate of talk and discussion around Subamarelha that one need not add to it. And yet I am most surprised to find audiences failing to accept Komal Gandharwhich I consider to be my most intellectual film. I have a hunch that the film will come into its own maybe after twenty or twenty-five years. It deals with a problem that may not have become intense enough for the Bengalis as to endanger their very existence. Anyway, in both the active and inactive phases of my life as an artist, I have realized that it is imperative for the artist to live in a state of daily struggle, struggling against a wide range of

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

inhibitions. Once in a while a crisis may overpower an artist temporarily, but that should not be allowed to drive him to compromise. In other words, we should never surrender to a crisis, and abdicate our conscience, our wisdom, our being. Originally published in Bmgaa as ~ar Chhabi', in the pe,iod.wJJFtlm, Autumn wue, 1966. Tronslal«I /;,J Samik Band.~.

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

The Film I Want to Make on Vietnam

For any filmmaker today, it would be a grave and sacred thought to think of making a film on Vietnam. It would be audacity and even a sin to talk about it lightly or without deep involvement. or without a serious study of all the facts about Vietnam. But that is the sin I will be committing in the course of this piece. Whatever I know about Vietnam I have gathered from the newspapers, a few pictures and features in some reviews. I have never been to Vietnam, and have never been able to feel its pulse. Still I have somehow got the impression that the event itself amounts to the turning over of a page of history. I have the feeling that Vietnam will give the course of world history a new . tum. . There is something else. To make a film I have to confine myself to Calcutta or to Bengal at the most. I do not consider it a hindrance. I would rather find it promising as a precondition for creativity in the arts. For the little that I have realized about Vietnam tells me that the fight in Vietnam is being fought here, too. For Vietnam stands as a symbol of protest against exploitation all over the world. It would be wrong maybe to take it for a symbol, it would actually stand for the ultimate extension of that protest. All the miseries and lamentations of our country have found a magnification in the war in Vietnam. That is someµung that the American ruling cla.s.1 has never realized, and tJ:iat is why Vietnam has stunned them. Or maybe turned them into a pack of rabid dogs. I have heard of filmmakers in the countries beyond the ocean who have planned to make films on Vietnam, and some have

Digitized by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

..

,4

Ritwilc Ghata/c

made them already. I am not speaking here of the journalist filmmakers who have recorded the war in Vietnam with great power. I am s~aking of those who live far away from Vietnam and have sought to be a part of the war there through the exercise of their intellecL They are bound to fail, I think. I have had the privilege of seeing a couple of films on Hiroshima inade by groups of the same kind. That experience has led me to this speculation. Yet another thing co~es to mind. A well-known French director has expressed his desire to make a film on Vietnam. Some years back he was offered a chance to make a film on Napoleon. The gentleman said that it was not Napoleon on the battlefield, nor the battlefield itself but the couch on which Napoleon slept with his women that carried the greatest meaning and artistic suggestion for him. Hence he would begin his film with that bed. It gives me the shivers to think what would happen if directors like him take on the theme of Vietnam. For Vietnam today has become a fad along with many more such issues. So-called intellectuals have jumped on to the bandwagon already. They can never feel or capture the cry that rises from the bleeding heart of Vietnam or her burning commitment. For like the American ruling class, they, too, will never feel the pulse of Vietnam. Like lkebana or the Bishnupur horse, Vietnam is one more toy that helps them remain modem. They can use it to identify with the dangerous trend of glorifying so-called human relationships. Let God take good care of them. Let me now share with you my thoughts on how my film sh