Philadelphia's Germans : from colonial settlers to enemy aliens 2021030996, 9781793651792, 9781793651815, 9781793651808, 1793651795, 1793651817

109 72 33MB

English Pages [343] Year 2021

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Cover

Half Title

Title Page

Copyright Page

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Notes

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Author Notes

Notes

Chapter 1: Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

With the Union Army

Notes

Chapter 2: A More Distant War—and Closer Peace (1866–1871)

The Franco-Prussian War

Notes

Chapter 3: Welcoming More Germans (1871–1881)

Philadelphia and Beyond

Citizens, Voters, and Candidates

Beer, Music, and “Jolly Germans”

Temperance and the Sabbath

Judging the Germans

Notes

Chapter 4: Liquor, Labor, and Politics (1882–1890)

Serving Needy Germans

Relocating and Adjusting

Politics and Labor

Temperance and Personal Liberty

New Initiatives, Old Images, New Self-Images

Notes

Chapter 5: German and Philadelphian (1891–1900)

Scenes of Daily Life

German Day

Language and Assimilation

Religion and the Germans

Becoming American; Remaining German

Power and Politics

Organizing Deutscher Michel

German Hospitality

Other Losses

Cholera and Immigration Restriction

Foreign Affairs and Political Loyalty

Hardy People—Good Citizens

Under a Scholarly Lens

At the End of the Nineteenth Century

Notes

Chapter 6: Germans in Tongue; Americans in Heart and Soul (1901–1916)

German Day: Ethnicity as a Commodity

War Comes to Europe

German and American

Notes

Chapter 7: The War against Enemy Aliens (1917–1918)

The Coming of War

Spies and Saboteurs

Restriction, Registration, and Internment

Confiscating Wealth and Property

The Palmer Postscript

Notes

Chapter 8: America’s First “Culture War”

The National German American Alliance

Foreign Voices

The Pastorius Monument

Notes

Chapter 9: Indemnities and Restoration

Notes

Epilogue

Appendix

Bibliography

Newspapers

Government Documents

Periodical Reference Works

Books

Articles

Index

About the Author

Citation preview

Philadelphia’s Germans

Philadelphia’s Germans From Colonial Settlers to Enemy Aliens

Richard N. Juliani

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham • Boulder • New York • London

Published by Lexington Books An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 86-90 Paul Street, London EC2A 4NE Copyright © 2021 by Richard N. Juliani. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Juliani, Richard N., author. Title: Philadelphia’s Germans : from colonial settlers to enemy aliens / by Richard N. Juliani. Description: Lanham : Lexington Books, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021030996 | ISBN 9781793651792 (cloth) | ISBN 9781793651815 (paperback) | ISBN 9781793651808 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: German Americans—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia—History—19th century. | German Americans—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia—History—20th century. | Germans—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia—History—19th century. | Germans— Pennsylvania—Philadelphia—History—20th century. | Immigrants—Pennsylvania— Philadelphia—History—19th century. | Immigrants—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia— History—20th century. | German Americans—Ethnic identity. | Philadelphia (Pa.)—History. Classification: LCC F158.9.G3 J85 2021 | DDC 305.83/10748—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021030996 ∞ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

List of Illustrations

vii

Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: Conceptualizing the German American Experience

1

1 Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

5

2 A More Distant War—and Closer Peace (1866–1871)

25

3 Welcoming More Germans (1871–1881)

39

4 Liquor, Labor, and Politics (1882–1890)

63

5 German and Philadelphian (1891–1900)

101

6 Germans in Tongue; Americans in Heart and Soul (1901–1916)

157

7 The War against Enemy Aliens (1917–1918)

193

8 America’s First “Culture War”

237

9 Indemnities and Restoration

273

Epilogue: A Search for Meaning

281

Appendix: Studying the German American Experience—A Brief Biographical Essay

291

Bibliography 303 Index 311 About the Author

327 v

List of Illustrations

Figure 1.1 Figure 1.2 Figure 1.3 Figure 3.1 Figure 4.1 Figure 5.1 Figure 5.2 Figure 5.3 Figure 5.4 Figure 5.5 Figure 5.6 Figure 6.1 Figure 6.2 Figure 7.1 Figure 7.2 Figure 7.3 Figure 8.1 Figure E.1

General John F. Ballier Brigadier General Henry Bohlen Colonel Francis Mahler Philadelphia Schuetzen Verein Reverend Adolph Spaeth U.S. Congressman Frederick Halterman Cannstatter Volksfest Verein at Washington Park (1897) Charles H. Reisser Godfrey Keebler Editorial Cartoon: Philadelphia Saengerfest (1897) Festive Turners March Advertisement—Wanamaker’s German Day Advertisement—Wanamaker’s German Day Charles J. Hexamer A German American Alliance Warning Sign—Forbidding Enemy Aliens How All of Us Feel—To Hell with the Kaiser Corporal Frank William Reinhart

vii

18 19 20 59 90 112 120 124 129 134 142 166 168 195 196 211 249 286

Preface

It is often instructive to know how any particular work came to be written. In the present case, it may have begun with a widely respected Philadelphian of German descent who, despite being the head of one of the largest pharmaceutical firms in the world, remained quite mindful of the difficulties that his family had endured a half century earlier. At a board meeting of a research center for the study of ethnic life in America, he mentioned that German Americans had been treated very badly during that time. His remark not only came as a surprise to others in the room but would not leave the memory of at least one of them. More than thirty years later, as I began research on how the Great War of 1914–1918 affected Philadelphia, the more that I read about those times, the strvonger my recall of his words became. My own parents, despite my mother having lived in America for over thirty-five years and my father for twenty years, became “enemy aliens,” required to carry identification cards and report annually to an office of the Justice Department in the early 1940s. I was only vaguely aware of it at the time, before becoming more so in later years, as I learned how difficult the lives of the foreign-born had sometimes been in ways that most other Americans knew little or nothing about. Although neither of my parents was ever interned as Japanese Americans and their families and some Germans and Italians were during World War II, I became concerned that such treatment ever happened. It is especially ironic that the sons of those families were highly decorated members of the armed forces of the United States during that war. Many of them never survived the struggle against America’s real enemies or returned from the battlefields to rejoin their own families. As the plight of German Americans in what was intended to be a brief reflection on local history evolved into the present study, while previous writers had examined much of this experience, I became convinced that we needed ix

x

Preface

to become even more fully reacquainted with it. Recent events have made many Americans wary of people from other parts of the world who as visitors, resident aliens, or even citizens seem to be “different” in some sense. Such fears evoke great parallels with earlier episodes of our history. Especially after the United States entered the war in April 1917, some Germans were believed to pose a threat to America. But the German American population as a whole, which included some of the oldest families in the nation, did not; and their sons who fought and died as American soldiers in the Great War of 1914– 1918 did not. It is these people that this work seeks to have us remember. T. S. Eliot once observed that “a people without a history is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern of timeless moments.” But in seeking what constitutes that “pattern of timeless moments,” we must decide what are the right elements and how they relate to each other. Marc Bloch, a great historian of an earlier era argued that “in the last analysis it is human consciousness which is the subject matter of history. The interrelations, confusions, and infections of human consciousness are, for history, reality itself.” But while a proposed study might include the right issues, historical research may be blocked by the unavailability of data. But historians tend to find a body of information and then ask what questions do these data answer. In contrast, sociologists, who study populations of still-living subjects, can frame questions that they deem to be worth raising, ask what kinds of data are needed to answer those questions, and then devise a methodology that generates those data.1 Since the time of Max Weber, sociologists have recognized that their research must be soaked in history. By the same token, good history is facilitated by the use of sociology to organize data. With the erasure of boundaries between history and sociology, fresh perspectives provide space for such new fields as Peter Burke calls “historical anthropology.” In seeking to recreate the past, the present study often relies upon a rich, but risky, resource—press coverage of events—as a prism through which they were refracted—but with a critical, rather than a blind, acceptance. As Bloch warned long ago, the newspaper as a source can put research on a sometimes treacherous course. While we might wish that newspapers would be nothing less than faithfully accurate cameras that capture and reveal history, they frequently, by their choice of what news to cover, placement of published articles, and use of language, become more like projectors that construct and cast the news of events. And if so, as newspapers, by their substance and tone become part of the narrative, it becomes necessary for caution to replace naïveté. But whatever its liabilities, the newspaper as a means of communication in the modern era has become a part of the process of history. It is with this understanding and in this spirit that we use this medium in a manner which even Bloch would have approved.2

Preface

xi

Whether as history or sociology, critical reflection remains a dangerous undertaking. For those who would ignore or deny what might be learned from it, their consciousness of past and present is limited or distorted. For those who celebrate a “heritage,” which offers a mythic, but comforting reconstruction while fleeing from actual events, their nostalgia can never rise above being anything more than a distraction for a public that has lost faith in the future. As we examine our cultural history, especially when it becomes uncomfortable, it is good to remember such cautions. It is within this spirit that the present work was conceived and conducted. NOTES 1. Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1992), 89. 2. Peter Burke, The Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Acknowledgments

I would be seriously remiss if I failed to acknowledge the advice, criticism, and encouragement that have been graciously and generously provided by a number of friends and colleagues over the time during which this study was being written. Daniel E. Hebding paused his busy teaching schedule and Albert Brancato interrupted his work with the German government to offer very early feedback of a preliminary version of this manuscript. Subsequently, James Niessen offered his criticism of a later version. Joseph Casino, who has attended the annual Cannstatter Harvest Festival every year since the early 1960s, was also well qualified to comment on the research and writing. Along the way, Spencer Di Scala has frequently responded to the intellectual and emotional angst of the author. I also need to thank Rachel Schaller for her indispensible advice and support on the preparation of this manuscript and Jutta Seibert for being an unfailing source on matters related to German culture and language. Similarly, Michael G. Ehrenreich and Charles Ladner, old and dear friends, have both long and proudly shared their more personal insights and experiences from within the group being studied. I especially wish to acknowledge the influence of the late Jim Bergquist, a colleague who taught me much about the German experience in Pennsylvania and should have been the author of a book like this one. I also wish to express my sincere appreciation to Eric Kuntzman as an editor who supported this work from its initial proposal, and Mikayla Mislak, as a production supervisor who gave meticulous attention to its final details at Lexington Books. And of course, none of my work escapes the invaluable response of my most trusted reader, critic and patient wife, Sandra P. Juliani, whose contributions can never be fully or adequately measured. I suspect that there have been other scholars and friends who have helped to facilitate my work, but who have been momentarily forgotten. To all of them I am most grateful.

xiii

Introduction Conceptualizing the German American Experience

The historian often discovers that a “conceptual model” is necessary to organize a myriad of details into a more efficient understanding of some particular subject matter. It is certainly true with the long story of the Germans as an immigrant group within the context of America as a society. The present research rests upon such an analytical scheme. It proposes six major dimensions of immigrant life and adjustment: (1) intentions (why did they leave their homeland; why did they come to any particular destination; and what did they expect to find at that destination); (2) images (how were they seen by Americans already here; how did it affect their adjustment to America); (3) identity (how did they see themselves; how did they see other immigrants from their own homeland; and how did they see other Americans); (4) interactions (what kinds of contact did they have with each other; what encounters did they have with other peoples; and what happened over time in these relationships); (5) cultural patterns and institutions (what did they bring with them from their homeland; what is left of what they brought; what did they build for themselves in adjusting to their destination; and what did they leave in impact on their new setting); and (6) the structural context of their new society (what material opportunities were available to them; what restraints were imposed on where and how they could live, work, and participate in their new locations; what were the economic and political boundaries of their settlement and adjustment). While relevant to any immigrant group, our intention is to apply this scheme, at least part of it, to the Germans who came to Philadelphia. In regard to the legacy of earlier scholars who have already explored the subject, the aim is simply “to expand the canvas.” To put the matter in even simpler terms, what is it that we seek to know better about the German American experience? 1

2

Introduction

In using this paradigm as a heuristic device, it becomes apparent that the six dimensions which have been introduced are variables that challenge the researcher. For example, the intentions of Germans as emigrants may have been an urgent aspect of their lives, but remain relatively inaccessible as data. How are we to know the “interior life” of Germans in the eighteenth century? Meanwhile, as one concern fades from relevance, virtually disappearing as a visible aspect of the narrative, another focus, such as the interactions of Germans with their Anglo-American neighbors, becomes a more important part of their experience. Thus, in the chapters that follow, it cannot be expected that each factor carries equal weight but rather varies in relevance and salience within a kaleidoscopic framework. It is similarly important to note that Germans, like other immigrant populations, existed in two parallel environments. The opportunities and limitations, the more “objective” material conditions, in which they found themselves provided the first dimension of their existential world. But the more subjective perceptions and judgments of others around them, providing for what a modified version of what W. I. Thomas called the “definition of the situation,” was no less real.1 And at times, this social psychological milieu of a constructed reality springing from the minds of others might even be more important in determining their lives. And while churches and synagogues, particularly in messages delivered from their pulpits, and legislative bodies by their enactments, and other government agencies by policies and implementation, as well as more private opinions expressed by citizens, also contributed their views, no institution more frequently and visibly described and assessed German character and behavior than the major newspapers of great cities. And by doing so, such portrayals in news coverage, editorials, feature articles, photographs, and even cartoons emerged as a principal instrument in “framing” the reality of German American life in urban America.2 In seeking to re-create the past, the present study often relies upon a rich, but risky, resource—press coverage of people and events—as a prism through which they were refracted—but with a critical, rather than a blind, acceptance. As Marc Bloch warned long ago, the newspaper as a source can put research on a sometimes treacherous course. But while we can see the newspaper as a liability, we can just as easily see it as an opportunity. Therefore, it cannot be quickly dismissed, but must be regarded as an important voice of its time. And while we might wish that newspapers would be nothing less than faithfully accurate cameras that capture and reveal history, we must remain aware that by their choice of what to cover, along with their placement of published articles and use of language become more like projectors that construct and cast the news of events. And if so, as newspapers by their substance and tone become part of the narrative, it becomes necessary

Introduction

3

for caution to replace naïveté. But whatever its limitations, the newspaper as a means of communication in the modern era has become a part of the process of history. It is with this understanding that we use this medium, especially when “cross-examined,” as Bloch advised, and in a manner of which he would have approved.3 The present narrative of German experience traces the journey of people who arrived in a virtual “dead heat” with the Anglo settlers of William Penn’s colonial experiment. But their adjustment and much of their future would be rooted in their reasons for leaving their homeland. They had fled a repressive state and restrictive society with the belief that they would find more promising opportunities and freedoms in America. They had not come seeking to control a new society, but to build their own self-contained community in a relatively isolated setting in which they would transplant their traditional customs and institutions. In this manner, they hoped to maintain continuity with their past along with the integrity of their present life. Instead, they faced, like new arrivals from other parts of Europe, a demand to become assimilated. But rather than quietly becoming American, they would declare a more complicated identity as they settled into the routines of life in Philadelphia. Assimilation was not a passive process that merely happened to them as immigrants, but one in which they became active agents in their adjustment to a new society. Seeking to maintain ties with their original culture, and at times to assert its superiority, they pushed back against what was being imposed by the “host society” and pursued their own course of becoming German Americans. Their elaborate and well-organized institutions enabled them to become a force that had to be reckoned with in local and national politics; and often expressing their presence by exuberant public celebrations, they challenged Anglo hegemony. But they also placed themselves in a position of vulnerability that would eventually become exposed under the duress of the Great War. While most German Americans followed an exemplary course of loyalty and service in military and civilian roles, the circumspect expression of heritage by others would invoke broader suspicions. And despite once being marked as a “model minority,” preferred as newcomers to other immigrant groups, German Americans were redefined by less tolerant political and cultural expectations, as a nation, galvanized by wartime exigencies, recast them as hyphenated “aliens” who threatened safety and security. Our account ends with the events of that moment not because German Americans ceased to exist, but because they had reached a decisive terminus as a foreign population of immigrant origins. And to pursue them any further as an ethnic group in subsequent years, as valuable as that might be, not only goes beyond the scope of the present undertaking but would require another book of similar length.

4

Introduction

AUTHOR NOTES The use of both “Schützen” and “Schuetzen” in this study reflects how these words appeared in sources at the time of the events being described. “Schützen” referred to the members of a local rifle club and “Schützen Verein” to their club, while “Schuetzen Park” was the spelling used for the local site where their activities took place. It is consistent with newspaper usage of the past and archival practices of the present. NOTES 1. For the original formulation of “the definition of the situation,” see W. I. Thomas, The Unadjusted Girl (Boston: Little, Brown, 1923). 2. In the case of Philadelphia, The Inquirer, founded in 1829, provided coverage of German life since the early nineteenth century. At one point, it would claim to have the second largest circulation among all morning papers in the nation. The Evening Ledger, a relative late comer, greatly expanded available information, after it first appeared as an evening newspaper in September 1914. Retitled as The Evening Public Ledger in December 1917, it would remain independent in reportorial and editorial staff from The Public Ledger, a morning daily paper, published since 1836, although both belonged to the Public Ledger Corporation. Although the city had numerous other newspapers, we have relied, for reasons of accessibility, mainly on The Inquirer for information for early years, but also The Evening Ledger/Evening Public Ledger after its founding. 3. For Marc Bloch’s indispensable critique of the sources of historical evidence, see The Historian’s Craft (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1992). For pertinent comment on newspapers in World War I, see pp. 89–91.

Chapter 1

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

From its earliest days, America has been challenged by the problem of peacefully integrating its diverse population. During colonial days, the confrontation of foreign settlers with indigenous peoples initiated a need to find a solution to social and political matters that remained to be fully resolved. The importing of African slaves established similarly formidable and enduring consequences. And beyond these “original sins,” while many newcomers came from the British Isles, vast numbers of immigrants further complicated matters in later years. It is not an incidental aspect of the struggle to become a cohesive society that the motto “E pluribus unum” emerged during the years of nation building. The challenge of finding national unity, order, and security would often erupt in regrettable chapters of the American past. In the case of German Americans, it was part of the much longer and broader experience that began with their early history. For German settlers in colonial Pennsylvania, their first task was to find a place in which they could stake their claim within the spatial and cultural boundaries of a new society. In their pursuit of that objective, Germans would achieve great success. When William Penn arrived in October 1682, some 3,000 Swedes, Dutch, Finns, and English had already settled on the banks of the Delaware River. An early author could declare: “The diversity of people, religions, nations and languages here is prodigious”; with Germans, Swedes, or Dutch comprising half of that population by 1750. Pennsylvania had “indisputably carried off the palm” as the most diversified colony by the time of the War for American Independence. George Washington would write: “Pennsylvania is a large state, and from the policy of its founder, and especially from the great celebrity of Philadelphia, has become the general receptacle of foreigners from all countries and of all descriptions.” But as early as 1726, with many settlers from the Palatine, James Logan, Penn’s Irish Quaker associate, noted: “We 5

6

Chapter 1

shall soon have a German colony.” The eminent architect, Jean Nicholas Louis Durand reportedly informed the Duke of Choiseul, France’s foreign minister, that “Germans, weary of subordination to England and unwilling to serve under English officers, openly declared that Pennsylvania would one day be called Little Germany.” And Benjamin Franklin, providing the bestknown objection, would ask, “Why should the Palatinate boors be allowed to swarm into our settlements, and, by herding together, establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvanian, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us, instead of our Anglicizing them?” But Franklin’s hostility failed to discourage German arrivals, who would lay claim to a special place, accompanied by a particular tension with the English, within the Pennsylvania colony.1 German Quakers and Mennonites, with Francis Daniel Pastorius, a member of a prominent Lutheran family of Franconia, as their agent and organizer, seeking to avoid religious persecution in their homeland, who arrived in 1683, only a year after Penn, represented the second founding of Pennsylvania. Having obtained a parcel of land in a northwestern corner of what would later become the city of Philadelphia, their farms, gradually spreading into the countryside, provided much of the food needed by the more concentrated English settlement on the Delaware. With gratuitous hyperbole, they were described as “an extremely industrious type” who produced various goods as their community became a center of early manufacturing.2 While Germans would be recognized as the first colonials to condemn slavery, their call to mobilize against the British in August 1775, nearly a year before the Continental Congress severed ties with England, deserves similar attention. Their leaders, along with the boards of Lutheran and German Reformed Churches, had prepared a pamphlet addressed mainly to their own members, but also directed to co-religionists with Tory sympathies in New York and North Carolina, describing the events at Lexington and Bunker Hill as well as the actions of delegates meeting in Philadelphia. It reported that Pennsylvania’s Germans had already formed militias and rifle corps, while others unable to join them would serve by whatever means they could. With this plea for a united effort, a local contingent, meeting at a Lutheran school house at Fifth and Cherry Streets, began drilling in late March of 1776. Two months later, after warfare had begun, the Continental Congress accepted the offer of service from a regiment of German volunteers, raised in Pennsylvania and Maryland. In his account of the ensuing conflict, Joseph G. Rosengarten described the German role in the rebellion: In the pages of that excellent and useful journal, Der Deutsche Pionier, the organ of the society established under that name to preserve everything that relates to

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

7

the history of the German settlers in this country, are found many records of the Germans who served the cause of American liberty, both in the Revolutionary war and in that of the Rebellion. . . . The records of the Continental army show that in almost every regiment, there were Germans, and in those of Pennsylvania, whole regiments, battalions, and companies organized, officered, and filled with Germans, who did good service for their country.3

The actions of Germans during the War for Independence would be “scarcely mentioned in our histories and not generally known even to their own descendants of to-day.” Under the rubric of “what history usually fails to tell,” revisionists would later claim that “too often our people are made to appear in a secondary role, following the lead of New Englanders, when they were actually in the front ranks.” But such observations, using a coded language in which “New Englanders” referred to a dominant majority, veiled an underlying tension with Anglo-Americans as persuasive speakers and scholars recounted what Germans did for the “great cause of liberty . . . that tried men’s souls.”4 After America gained independence, Germans often displayed a dual allegiance. In October 1825, as their homeland began its own passage toward nationhood, Philadelphia’s Germans honored Charles Augustus, the Duke of Saxe Weimar, an early advocate of German unity, by a banquet, whose guests included President John Quincy Adams, which also marked the 143rd anniversary of William Penn’s arrival in Pennsylvania. Seven years later, in September 1832, community leaders summoned Germans to Commissioners Hall on North Third Street in Northern Liberties to form a union and find measures “to assist the patriots of Europe in establishing the freedom of the Press in Germany.” The same notice invited all who cherished the welfare of Germany or the principles of American liberty to attend the meeting. But while politics brought them together, Germans did not ignore their cultural heritage. In June 1840, they celebrated the 400th anniversary of Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press by a grand parade and musical concert at Independence Hall, and a lecture by Daniel M. Keim, a prominent lawyer, businessman and scholar, on German contributions to the art of printing, at a banquet in Gray’s Ferry. But occasional newspaper items also claimed that Philadelphia’s Germans were joining another movement sweeping the nation by forming temperance societies in the early 1840s, a curious initiative in view of later events.5 As Germans sought to find their way in a new setting, with other Americans attempting to place them into an appropriate social location, language emerged as a civic issue. In May 1830, newspapers in Philadelphia editorially disputed the proper place of German in public education. The Philadelphia Gazette maintained that the great number of German-speaking pupils among

8

Chapter 1

the 300,000 school-age children in the state made it unfeasible to teach them in their ancestral language. The Inquirer noted that while many Germans held their past with “true veneration,” they were, nevertheless, as citizens of Pennsylvania who cherished its interests and identified themselves with its policy, no different than French or Irish residents, but with the more basic matter being the taxation and financing of public education. The debate over language, even with the increasing assimilation of Germans, would remain a troublesome matter in future years.6 In June 1837, parts of Northern Liberties could be described as so thickly settled with Germans that an onlooker might believe himself to be in the “fartherland (sic) of marvels, metaphysics and music.” Not only were signs on stores written in German, but buyers and sellers, along with market people and wagoners, were German, while “an infinitude of little urchins in the streets discourse in this dialect.” In places of public entertainment, the language was used to discuss national affairs and politics as well as for small talk. Instructive lectures were given on week day and orthodox sermons on Sundays. While some of the most eloquent preachers were German, their mental fire was doused by the absence of Americans to hear them. Numerous clubs and associations, as well as a newspaper, which probably enjoyed abundant patronage, could be found. The rich, full, and strong musical bands of the German Guards, with a military presence in appearance and discipline, were expected to soon be able to perform as well as their counterparts in Europe. And a German theater, composed of amateur actors, had recently opened. The Germans of Philadelphia as a whole were “industrious, sober, intelligent, and willing observers of the laws of the state and land,” who represented an early “model minority.” With the size of their population, their prowess in economic and political affairs, and the growing strength of their institutions, they were hardly a minority; yet the future would find them greatly challenged.7 By the 1840s, political gatherings, accompanied by a musical band or choral group, often gained the attention of many Germans. In early November 1842, an estimated 12,000–15,000 marchers, behind a “German Battalion” of artillerymen, Jäger riflemen and other units, escorted former vice president Richard M. Johnson along the old Germantown Road in a grand public event that brought the local settlement to the rest of Philadelphia. But a few days later, German efforts to welcome Robert Tyler, the son of President John Tyler, when he visited John C. Montgomery, recently appointed as city postmaster, became a more modest, almost private, affair. After an impromptu concert by a band and singers, Germans, disappointed that the younger Tyler could not extend his stay, listened as he thanked them for supporting his father as president of the nation.8 The “German Battalion” that had accompanied Johnson on his visit to Philadelphia were volunteers, first organized in 1836 under Bavarian-born

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

9

Captain (later Major) Frederick Dithmar, a well-known brewer of porter, ale and lager, whose business was located on North Third Street in the heart of the German district. Beyond marching in patriotic celebrations or serving as an honor guard at funerals of deceased members of various military units, the “German Battalion” embraced more serious duty during the brief but violent riots in Southwark District in July 1844. In his report to the Governor of Pennsylvania, Major General Robert Patterson cited Dithmar and his German guardsmen for their efforts against the mob that had been confronted at St. Philip Neri and along Green Street between South Third and South Fifth Streets. In a letter to a local newspaper, “an actor on the scene” bestowed even greater praise on the German volunteers and American cavalry who charged under surrounding fire down Green Street and broke the resistance of the rioters.9 With public order restored, the “German Battalion” resumed more customary duties at parades and funerals. But whether quelling disturbance or participating in more peaceful ceremonies, Philadelphia’s Germans had to allay fears of other citizens, fueled by rumors and newspaper reports, that some German states had been sending criminals and paupers to America. In late 1844, Georg Friedrich List, the influential economist who had immigrated to Reading, Pennsylvania, become an American citizen, and worked as a journalist, before returning to Germany as the U.S. Consul at Leipzig, claimed that the smaller governments of Saxony were preparing to empty jails and workhouses by exporting inmates. List, who would be compared to Marx as an economist and praised as an early contributor to European unity, strongly objected that such action was against international law and inimical to America as a market for German manufacture. He noted that towns and boroughs in Germany had used public funds to finance passage by which they could rid themselves of less desirable residents. But if such policies were being carried out, German Americans would also have an occasional impact on politics in Germany. Buried in news from Berlin, a dispatch reported that an inflammatory message from Philadelphia, posted on the walls of a church, had urged the local parliament to depose the reigning sovereign and establish a republic. The petitioners, whose political appetite could not be fully satisfied in an American city, had apparently not forgotten their homeland.10 Despite the failure of the revolutionary movement of 1848, Philadelphia’s Germans, honoring refugees, exiles and other cultural heroes, maintained their support for republican politics. In October, they feted the “distinguished patriot” Friedrich Hecker, at the City Hotel on North Third Street, above Market Street. Received with great enthusiasm over several days, Hecker, probably the most prominent German revolutionist of his time, would become one of the founders of the new Republican Party and a strong supporter of Abraham Lincoln in America. By 1849, German efforts included

10

Chapter 1

soliciting material aid for countrymen who sought refuge in Switzerland. While Germans had long endorsed European republicanism, Philadelphia held one of its largest “monster meetings” in August, as Louis Kossuth’s doomed campaign to gain independence for Hungary entered its final days. Forced to flee to America, he soon found himself pursued by solicitous supporters. In 1851, when Philadelphia Germans sought to honor him, Kossuth declined their invitation. Although their alternative proposal of a torch-light reception, with all citizens invited to participate, was similarly refused, such intentions showed a staunch commitment to democratic values.11 While preoccupied with current politics, Philadelphia’s Germans held fast to their memories of the past. In late summer 1858, they prepared to honor Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who had helped to train the Continental Army at Valley Forge in 1778, but had not yet gained recognition by any monument or public event. Plans called for Morton McMichael, publisher of the North American and United States Gazette, and other prominent citizens as principal speakers for the occasion, along with entertainment by German bands and musical societies. In early September, a huge parade, led by the mounted Harmony Brass Band, followed by eleven divisions of other musical units and patriotic societies, formed on Ridge Street above Vine, and marched past crowded sidewalks to Center City, and finally to Lemon Hill in Fairmount Park. From a German garbed in a clown costume amusing spectators to the assembled members of the German American Beneficial Association, closing their long line, marchers captured the spirit of the day, as families filled omnibuses on their way to the park. Over the next two days, orations in both English and German, singing performances, gymnastics demonstrations, and rifle contests engaged the public. For serious men in black suits, wearing brown Kossuth hats and handsome rosettes who heeded solemn orations and revelers who found greater depth in beer kegs and impromptu performances, the event was deemed to have been “the greatest German jubilee ever witnessed in Philadelphia.” The final tally of 12,000 attendees, $2,600 in receipts, and a net profit of $1,742, contributed to the $10,000 cost of the monument expected to come from all cities, as local Germans acquitted themselves well, at least in a financial sense, by the occasion.12 While the von Steuben Festival reclaimed a neglected hero, Philadelphia Germans, coming together in far greater number than on any previous occasion, had drawn as much attention to themselves as to their patriot. They had marched behind German and American banners. They had taken their places in the parade alongside of “Americans.” They had spoken and sung in German. They had honored one of their own who, like themselves, came from Germany to serve America. But by embracing being American without letting go of being German, their historical observance strengthened cohesion and reconstructed identity. And as Philadelphia celebrated von Steuben, its

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

11

Germans were collectively finding themselves. They had acted as German Americans. In November 1859, Philadelphia’s Germans recalled an even more distant aspect of their aspect heritage with the centennial of the birth of the poet, playwright, historian and philosopher, Friedrich Schiller. Seeking funds to purchase his birthplace and dedicate a monument in Germany, a procession over city streets, greeted by a volley of 100 cannons, reached the Academy of Music where marchers piled their torches into a burning heap. In the German district, illuminated transparencies in front of music halls and newspaper offices projected vivid images of William Tell and other heroes of Schiller compositions. On the next night, a German orchestra and nine singing societies with over 200 voices performed, before Gustavus Remak, a native of Prussian Poland, now a prominent local lawyer, delivered an oration. But the principal address would be given in English by William H. Furness, the translator of Schiller’s epic poem “Das Lied von der Glocke” (“The Song of the Bell”). After Wagner’s overture to “Lohengrin” and a poem by Ferdinand Freiligrath, renowned as a revolutionist and poet, a statue of Schiller was unveiled, with a musical tribute by the Maennerchor Society. Meanwhile, “Kabale und Liebe,” a five-act drama by Schiller was presented at the German Stadt Theatre on Callowhill Streets. On the next day, students from German schools offered their own program at Mechanics Hall at North Third and Green Streets. But the less fortunate were not forgotten, with one-third of the proceeds from the Academy of Music event being turned over to the Society for the Relief of Poor and Destitute Germans. A letter from President James Buchanan saluted the proceedings. And The Inquirer declared “Among all the cities where the anniversary of Schiller’s centennial birth-day was celebrated yesterday, the Germans of Philadelphia, we venture to say, have done most to honor the name of their best poet.”13 Such celebrations conveyed much about the position of Germans in Philadelphia and indeed in America. While establishing themselves in a more or less self-contained enclave, they had increasingly found opportunities to express their collective presence on ceremonial occasions. And by fueling their solidarity as Germans, such moments served as a precursor to even grander occasions that beckoned in the future. Yet, as they stepped onto the path of becoming German Americans, their assimilation would be greatly illuminated by what they still cherished of their earlier origins in a homeland from which they had departed, but had not fully forgotten or abandoned. Meanwhile, for other Philadelphians, newspaper coverage promoted a wider awareness of an urban village inhabited by Germans as it became a more salient facet of the local scene. But Germans would soon find an even more convincing way of validating their new allegiance as Americans in the struggle to preserve the Union.

12

Chapter 1

WITH THE UNION ARMY With the outbreak of the Civil War, Philadelphia’s Germans, after nearly two centuries of peaceful endeavors, would emphatically affirm their presence in the crucible of the battlefield. In April 1861, only five days after Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, Germans, enlisting as volunteers in hastily assembled military units, reportedly comprised most of the 202 men of the First Rifle Battalion at its headquarters on Callowhill Street. Under the command of Major John F. Ballier, they were assigned to the Second Infantry Regiment of the First Division of Pennsylvania Volunteers. Within a few weeks, the redesignated Twenty-First Regiment, mustered in Franklin Square. On May 25, with reports of early fighting in Virginia, their unit, behind a regimental band, mounted officers and baggage wagons, marched to Suffolk Park to await further orders. Along the way, two young vivandière, in tricolored skirts and beaver pelt high hats, full of life as they kept in step, embellished the scene. Having already been praised in rifle drills, German recruits, carrying muskets of an earlier era, had now joined the fight against the Confederacy.14 As hostilities began, a Richmond, Virginia newspaper noted that the Federal army consisted largely of German and Irish men, who “always made splendid soldiers, and whose courage and endurance are proverbial.” The actual number of Germans who wore Union blue or Confederacy gray remains unknown, but claims reach as high as 100,000 to 200,000 of them for the Northern army. While their performance also remains difficult to assess, Joseph G. Rosengarten, the son of immigrants and veteran of the 121st Pennsylvania Infantry, before becoming a prominent lawyer, sought to fill this gap by a comprehensive study, first presented in a lecture at the German Society of Pennsylvania in 1885, Published as a book in the following year, and a revised edition in 1890, he noted the long record of distinguished soldiers of German birth or descent who had brought the training and experience acquired in their native country to the service of “their new fatherland.” Perhaps the most familiar name was reputedly the great grandson of a Hessian officer in the British army during the Revolutionary War, who settled in Pennsylvania after Burgoyne’s surrender, where he Anglicized his name from the original “Küster” to the more easily pronounced “Custer.” His flamboyant offspring, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, would achieve much fame in the Civil War, then in the Indian Wars before his death at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. But Lieutenant John T. Greble had a stronger German lineage as well as greater relevance to Philadelphia’s Germans. After emigrating from Saxe-Gotha in 1842, his great grandfather, Andrew Greble, had settled in the city, where he and four sons joined the Continental Army and fought at the battles of Princeton and Monmouth.

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

13

Rosengarten claimed that one of the younger Grebles, born in Philadelphia, a graduate of West Point, and a member of the First Artillery, was the first officer to die in the Civil War, while attempting to save other men at Big Bethel, Virginia, in June 1861.15 It, however, is in their more collective story that Philadelphia’s German soldiers reached significance in the Civil War. Many of them, soldiers before leaving their native country, arrived with a military zeal that had encouraged the formation of a militia in Philadelphia in 1836 which provided recruits for the Mexican War and entire regiments for the Civil War. And when rebellion broke out in the South, old comrades of the 1848 revolution in Germany and their sons were among the first to offer their support to the Union, with nearly a hundred officers of German birth in the regular army and many more among as field officers of the volunteers. In Pennsylvania, Germans had formed entire regiments and in other states their own companies within regiments, while volunteers could be found scattered in mixed regiments. And when they returned to earlier pursuits without seeking any other reward for what they regarded as a sacred duty at war’s end, Rosengarten argued that their service had earned them the right to American citizenship.16 Dismissing a German source that claimed over a million persons of German birth or descent as Pennsylvania residents, Rosengarten relied on reports of the U.S. Sanitary Commission that gave a far lower figure of 138,244 Germans in the state, with 17,208 of them having served in the Union army, a total exceeded only by New York, Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois. The 187,858 Germans for all states easily surpassed any other foreign origin group, with 139,052 Irish a distant second. Among volunteers in the regular army, many soldiers of German birth had obtained commissions as officers. But foreign-born personnel, among all 2,500,000 men who served, whether as enlistees or conscripts, tended to fall below their proportion of the total population. Rosengarten’s state-by-state inventory of units comprised entirely or mainly of men of German origins, included the First German Regiment of the 74th Pennsylvania Infantry and the Second German Regiment of the 75th Pennsylvania Infantry. Within the ranks of the Confederate army, Gustav Schleicher, born in Darmstadt in 1823, before immigrating to San Antonio, would distinguish himself by earning the rank of colonel, then as the first German elected to Congress after the war, where he gained a reputation as a representative of all Germans in the United States. But Southern sympathizers, promoting their cause in Europe, would find that Germans, swayed by profits from investments, remained far more supportive of the Union. While Germans joined the Confederate army, some in all German units, a much greater number of them served with Union forces. They belonged, as Rosengarten asserted, to an important chapter in the unwritten history of the war.17

14

Chapter 1

Rosengarten, relying on Samuel P. Bates’s five-volume History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865, wrote that many Germans, including some whose ancestors had been among the earliest settlers, had joined the first five companies formed in Pennsylvania at the start of the war. Of the 25 regiments raised for three-month service in what was expected to be a brief war, ten of them consisted mainly of Germans, including the 18th Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Wilhelm, and the 21st Regiment under Colonel Ballier, of Philadelphia. By early August, both regiments would be disbanded with their recruits mustered out of service. But as the conflict intensified, newly organized three-year regiments in Pennsylvania and other states bore the brunt of the war. The 27th Regiment, reorganized as a threeyear light artillery unit in May 1861, consisted entirely of men recruited from the districts of Northern Liberties and Kensington of Philadelphia, at least one-half of them being German, with many having already seen military service either in this country or Europe. Beyond regiments formed in the city, men of German birth or descent were amply found in other units raised in surrounding counties. Rosengarten regarded the ceaseless supply of German soldiers, experienced in wars of their homeland, who greatly strengthened the regular army as noncommissioned officers, as nothing less than “a great stroke of good fortune when a volunteer company had one of these welltrained and well-disciplined men in its ranks,—he steadied the whole line, and gave it an example of soldierly existence in every particular.”18 Within the 74th Infantry Regiment, organized in Pittsburgh with recruits from counties across Pennsylvania and the city of Philadelphia during the summer of 1861, the names of principal officers—Schimmelfennig, Hamm, von Hartung, Hoburg, Freyhold, von Mitzel, Veitenheimer, Blessing, Schleiter, Klenker, and Rohbach testified to its highly German character. Colonel Alexander Schimmelfennig, a former Prussian army officer, member of the Communist League, personal friend of Carl Schurz, and activist in the republican movement of 1848, before migrating to the United States in 1854, took command of the 35th Pennsylvania Infantry at Fort Wilkins in early September 1861. Increased by newly recruited men from Philadelphia, comprising Company K, under Captain Alexander von Mitzel, it encamped near Washington, DC. Receiving arms, uniforms and equipment and redesignated as the 74th Infantry Regiment, but sometimes still referred to as the 1st German Regiment of Pennsylvania, it would distinguish itself in several of the most important battles of the war—Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg—before being decommissioned in August 1865. The words inscribed at Schimmelfennig’s grave at the Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading, after his death in September 1865, easily applied to other comrades who had served their adopted nation: “A German by birth; An American in death; he wrote his name on the hearts of his countrymen.”19

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

15

Philadelphia Germans occupied the ranks of the 75th Infantry Regiment in even greater numbers, under officers whose names—Bohlen, Schapp, Mahler, von Matzdorff, and Ledig—reflected their origins. Known as the 40th Pennsylvania Volunteers while training at Camp Worth in West Philadelphia under Colonel Henry Bohlen, a veteran of the Mexican and Crimean wars, in August 1861, many recruits were veterans of European wars. Commended for their discipline and skill in drills, some 800 members, with upgraded rifles having replaced antiquated weapons, filled its ranks when it reached Washington. It was assigned to the Third Brigade, 2nd Army Corps, as a division of the Army of the Potomac under General Louis Blenker, another former officer in the Bavarian army who had migrated after the 1848 revolution. In April 1862, it marched into Virginia, then slowed by heavy snowfall and scarce provisions, before encountering an unanticipated tragedy. Attempting to cross the rapidly coursing Shenandoah River in pursuit of General Thomas J. “Stonewell” Jackson’s forces, three officers and 50 enlisted men drowned with the sinking of an improvised ferry, leaving a horrific scene of floating knapsacks as bodies slipped beneath the waters. Among many victims recruited in Philadelphia, Sergeant Joseph Tiedemann, son of a prominent physician, although regarded as an expert swimmer, lost his life in an unsuccessful attempt to save his captain. His brother, Adjutant Frederick Tiedemann, who had also been believed to have drowned, reported the incident to the press. In early June, the regiment, assigned to protect the left flank of Union forces at the Battle of Cross Keys, came under intense enemy fire while covering their retreat, until being forced to withdraw. In the aftermath, the reorganization of Union forces transferred the regiment to the 3rd Brigade of the Army of Virginia, with Blenker replaced by General Carl Schurz as division head, but with the regiment being held in reserve. In August, it arrived too late to take part in the Battle of Cedar Mountain. Even worse, despite being mainly engaged in brief skirmishes, it would lose General Bohlen as he led reconnaissance on the Rappahannock River to a Rebel marksman. Incurring an even odder loss, its band, led by Rudolph Wittig, who would be later acclaimed as a composer of war songs, and 15 German musicians recruited in Philadelphia were summarily dismissed by a general order. In August 1862, it entered into more formidable action at the Second Battle of Bull Run, in which two officers and 28 men lost their lives, and five officers and 98 men were wounded. Receiving lavish official praise for gallantry under fire, but little consolation for losses, its men, with the arrival of autumn, finally found some respite from raging waterways and battlefield violence.20 The 75th Regiment, reinforced by fresh replacements and returnees discharged from hospitals, was deployed in defense of Washington, DC, before being moved back into the field for the most decisive encounter

16

Chapter 1

of the war, as an old nemesis, “Stonewall” Jackson, unleashed 40,000 men at Chancellorsville in early May. Bearing the brunt of attack, the regiment, separated from command and scattered into disarray, hastily retreated, with significant numbers of men captured, before being relieved by reinforcements. Demoted to second line support of an artillery battery, it awaited assignment as a massive buildup of troops revealed that a more significant engagement was imminent. On July 1, after a 14-mile march, some 258 fatigued men, under Colonel Francis Mahler, resting in a field east of Carlisle Road, north of the village of Gettysburg, suddenly found themselves in the midst of action. Attacked by Confederate troops, they regrouped on Cemetery Hill. The wounded Mahler, extricating himself from beneath his fallen horse, urged his men, despite heavy enfilading fire, to hold their new position against enemy charges. Wounded a second time, Mahler would die a few days later, but his regiment, under continued shelling, stood firm. After three days of fighting, some 31 officers and men had been killed, 100 more wounded, and six others captured. With victory secured, the 75th Regiment marched south, sometimes under heavy rain, in pursuit of Robert E. Lee’s retreating forces. On their return to Philadelphia in early January 1864, its members, granted a 30-day furlough, would march with “a very creditable appearance” in their home city. But with some 75 war-weary men refusing the call to re-enlist being temporarily assigned to an Illinois regiment, the 75th Regiment, bolstered by new recruits, left for duty in Tennessee.21 With the war shifting in favor of the Union, the men of the 75th Regiment expressed their confidence in an increasingly inevitable outcome. Writing from Waverly, Tennessee, one soldier, prompted by his belief that friends of the regiment would like to hear of its whereabouts described recent happenings in a letter to a Philadelphia newspaper in September 1864. Ordered to protect bridges and railroad lines that enabled the movement of supplies to General William Tecumseh Sherman’s forces on their devastating march through the South, nothing of a warlike character had recently occurred except an occasional “gobbling up a few of the Johnnys.” A patrol, carried out on horses obtained from local farmers, had captured two Confederate cavalry men. With no change in officers, the health of the regiment remained very good, largely due to the skills of its two surgeons. Assessing the political climate, the writer believed that people throughout the area were “strongly Secesh,” but hearty advocates of General George C. McClellan for president and Representative George H. Pendleton for vice president in the upcoming election. In his ambiguous conclusion, the soldier-pundit opined that while a week among the Rebels would convince uncertain voters that they were doing all that could be done for the nation, his comrades in the 75th Regiment remained steadfast in loyalty to President Lincoln and the Union cause.22

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

17

From autumn of 1864 through most of 1865, the 75th Regiment continued operations in Tennessee, mainly guarding trains, providing reconnaissance and serving provost duty, with occasional minor skirmishes that included defending itself against irate civilians. Four months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, it was mustered out of military duty on September 1, 1865, with 236 discharged men reaching Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 12 days later. But the returning soldiers lost little time in doing their part to acknowledge their own effort in preserving the Union on their return to Philadelphia. On September 22, a committee of them called upon the mayor to present their regimental banner with the expectation of having it placed in Independence Hall.23 Among Rosengarten’s hagiographic portraits of men with ties to Philadelphia, General Galusha Pennypacker, born at Valley Forge in Chester County, was a descendant of Heinrich Pannebäcker, who had migrated and settled on Skippack Creek in the late seventeenth century. Although other members had scattered themselves in Montgomery, Chester and Berks counties, the family name, altered to its more familiar form, would become highly visible in the later development of Philadelphia. After entering military service in April 1861, as a noncommissioned officer of the Ninth Pennsylvania Volunteers, a three-month unit recruited across the state, Pennypacker rose in rank until he became the youngest officer in either the Union or Confederate army as a Brigadier General. For his actions at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in January 1865, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Remaining an officer until retirement from active duty in 1883, his death in October 1916 was attributed to complications from wounds received in battle a half century earlier. John F. Ballier, born in Würtemburg, who studied at a military academy at Stuttgart before coming to Philadelphia, became a member of the Washington Guard, the first German military organization in the North in 1836. After enlisting in the First Pennsylvania Regiment for the War with Mexico, he reached the rank of colonel in command of the 21st Infantry Regiment, then the 98th Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. Twice seriously wounded, Ballier weathered a court martial for insubordination, survived the war and returned to Philadelphia, where he purchased a hotel and saloon which he operated at North Fourth Street and Fairmount Avenue. Appointed as an Inspector at the U.S. Custom House in the city in 1866–1867, he was elected as a City Commissioner in 1867–1870. He retained the rank of Colonel of the 3rd Regiment of the Pennsylvania National Guard from 1869 until his retirement in 1876. Active also in the German community, Ballier was a co-founder of the Cannstatter Volksfest Verein in 1873, a board member of both the German Hospital and the German Society of Pennsylvania, before his death at the age of 77 in February 1893. After other notable Philadelphians

18

Chapter 1

marched across his pages—General Isaac J. Wistar; General William J. Hofmann; General Adolph Bushbeck; General Henry Bohlen; the Vezin brothers—Oscar, Henry, and Alfred; General John A. Koltes, who would die at the Second Battle of Bull Run; Joseph Tiedemann, drowned in the Shenandoah River, and his brother Frederick, the unfortunate one who had to report the news of it—Rosengarten ended his parade with a shining cameo of General Louis Wagner.24 The contributions by soldiers of German origin to the success of the Union army gained special recognition in Germany. Only ten days after Lee’s surrender, the legislative body of the free city of Bremen, before taking up other business, listened to an impassioned president judge as he proclaimed, “Many of our sons are fighting in the ranks of the Federal army, and the men of freedom and the Germans have shown that persistency and valor must finally conquer victory (sic), even over the infuriated struggling elements of the enemy.” When he asked for a show of sympathy for the victorious North, the entire assembly rose from their seats and cheered the Union.25

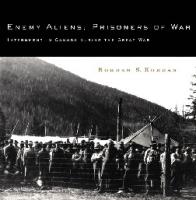

Figure 1.1 General John F. Ballier. Source: Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

19

Figure 1.2 Brigadier General Henry Bohlen. Source: Civil war photographs, 18611865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Rosengarten’s enthusiastic account of the Civil War easily gave the impression that no one but Germans could be found on its battlefields. It was reaffirmed by his inclusion of remarks by Andrew D. White, the first president of Cornell University and former U.S. Ambassador to Germany, delivered at the centennial celebration of the German Society of New York. Addressing “Some Practical Influences of German Thought upon the United States,” the staunchly pro-German scholar and diplomat expressed his hope that “the healthful elements of German thought will aid powerfully in evolving a future for this land purer in its politics, nobler in its conception of life, more beautiful in the bloom of art, more precious in the fruitage of character.” Rosengarten added his own belief that what the Germans had done for the country gave the best assurance that White’s fervent prayer would be granted. Their recent actions “to show their share as soldiers in the wars of the United States” validated the right and duty cast upon them to see that no injury

20

Chapter 1

Figure 1.3 Colonel Francis Mahler. Credit: Mathew Brady (Washington, D.C.)

should ever fall upon their adopted nation. Rosengarten’s earnestly expressed conclusion fully captured the conviction of many German Americans.26 Rosengarten’s brief book was a heroic attempt to document the presence, if not the contributions, of Germans to the military history of America from the War for Independence to the Civil War. But it also revealed itself to be a nearly impossible task, despite being supported by the documentation provided by Bates and others. Yet, even as an incomplete fragment of that actual experience, his effort, which sometimes made Union troops appear to be almost a mercenary army, recruited in Bremen and other parts of Germany, presented the Germans as an indispensable component of American forces at a time of an unprecedented crisis. As indisputable testimony of their value to an adopted nation, it is difficult to believe that later events could ever alter that judgment. NOTES 1. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Statistics of the Population of the United States at the Tenth Census (June 1, 1880). Volume I, Population, 457–8. For

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

21

Franklin’s remark, written in 1751, see his Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, &c. (Boston, 1755). Franklin did not allow his reservations about the increasing immigration to interfere with his willingness to publish hymnals and other religious books in German, as well as the Philadelphia Zeitung, possibly the first German language newspaper in America and to use German type in printing. Oswald Seidensticker, German Day (German Society at Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania, 1892), 12–16. Seidensticker, born in Gottingen, Germany in 1825, earned a doctorate in philosophy, before following his father, a lawyer deported for his political activities, to America in 1846. After teaching at secondary schools in Boston, Brooklyn and Philadelphia, the younger Seidensticker became the first professor of German Language and Literature at the University of Pennsylvania. His innovative and eclectic scholarship earned him acclamation as the “father of German American historiography,” while he also maintained an influential role in the community, before his death in January 1894. http://www.archives.upenn.edu/peopl e/1800s/seidensticker_oswald.html and Joshua L. Chamberlain (ed.) University of Pennsylvania (Boston: R. Herndon Company, 1901). 2. “Germantown Celebrates 232d Birthday Today,” Evening Public Ledger (October 6, 1916). Marion Dexter Learned, The Life of Francis Daniel Pastorius, The Founder of Germantown (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1908). 3. A summary of Professor Seidensticker’s research “In Memory of GermanAmerican Patriotism,” appeared in The Pennsylvania German, VII; 9 (September 1907), 451. For the 209th anniversary of their arrival, celebrated in October 1892, Seidensticker prepared a chronology of the Germans in Pennsylvania from 1626 to 1870 with listings of churches, organizations, and newspapers; biographical sketches of prominent residents of German origin; and related ephemera. For Joseph George Rosengarten’s remarks, see The German Soldier in the Wars of the United States (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1886), 34–5. The first version of his text had been presented in a lecture to the Pionier Verein at the German Society in Philadelphia on April 21, 1885. It was then printed in the June, July, and August issues of The United Service, a monthly magazine of military and civil affairs. Translated into German, it appeared in successive issues between June and October of the Nebraska Tribune, before being published as a pamphlet by J. B. Lippincott. After “numerous applications, showing interest in the subject,” Rosengarten, prepared the 1886 edition. 4. “In Memory of German-American Patriotism,” The Pennsylvania German, VII; 9 (September 1907), 446, 451. 5. “Items,” The (Boston) Columbian Centinel American Federalist (October 22, 1825); “Public Meeting,” The Inquirer (September 6, 1832); “Fourth Centennial Celebration,” The Inquirer (June 19, 1840); “Germany and the Art of Printing,” The Inquirer (July 1, 1840); untitled, The (Baltimore) Sun (July 13, 1842); untitled, The (New Orleans) Daily Picayune (July 30, 1840). 6. Editorial, The Inquirer (May 28, 1830). 7. Untitled, Philadelphia National Gazette and Literary Register (June 29, 1837); “Germans In Philadelphia,” Baltimore Gazette And Daily Advertiser (July 3, 1837). 8. “Local Affairs,” Public Ledger (November 1, 1842); “Local Affairs,” Public Ledger (November 8, 1842).

22

Chapter 1

9. “Military Report In Relation To The Southwark Riot,” North American and Daily Advertiser (July 25, 1844); “Give Unto Cesar (sic) The Things That Belong To Cesar (sic),” Public Ledger (July 25, 1844). Dithmar, preoccupied with the formation of a new military unit, dissolved his long partnership with George Butz in October 1862. He was involved in a collision with a train of the Germantown Railroad in which his wagon was destroyed and horse killed in October 1865. Dithmar died at the age of 66, on March 7, 1869. His life can be traced from numerous business advertisements and other items in local newspapers. 10. “Emptying Their Prisons,” Public Ledger (December 12, 1844); “Criminals From Germany,” Public Ledger (December 25, 1844); “Arrival Of The Brittani (sic),” North American and United States Gazette (June 27, 1848). 11. “Local Affairs—Festival to Mr. Hecker,” Public Ledger (October 13, 1848); untitled, Pennsylvania Freeman (October 19, 1848); “Grand Mass Meeting In Independence Square,” Public Ledger (August 21, 1849); untitled, The (Trenton, N.J.) State Gazette (December 12, 1851). 12. Untitled, Charleston (S.C.) Mercury (August 17, 1858); “German Mass Meeting—Proposed Festival,” The Inquirer (August 19, 1858); “German Festival,” The (Baltimore) Sun (August 20, 1858.); “Local Affairs—Steuben Festival,” Public Ledger (September 06, 1858); “Local Intelligence—The Steuben Festival,” The Inquirer (September 7, 1858); “Local Affairs—the Steuben Festival,” Public Ledger (September 8, 1858); “Baron Steuben,” North American and United States Gazette (September 7, 1858); “Local Intelligence—The Steuben Fund,” The Inquirer (September 28, 1858). 13. “Local Intelligence Schiller Jubilee,” The Inquirer (February 9, 1859); “Local Intelligence—The Schiller Celebration,” The Inquirer (September 21, 1859); “Local Intelligence—he Schiller Festivities,” The Inquirer (October 26, 1859); “Local Affairs—The Schiller Festivities,” Public Ledger (October 26, 1859); “Local Intelligence—The Schiller Celebration,” The Inquirer (November 5, 1859); “The Schiller Centennial Celebration,” The Inquirer (November 7, 1859); “Local Affairs— Schiller Centenary Celebration,” Public Ledger (November 8, 1859); “Amusements, etc.—The Schiller Festival,” The Inquirer (November 9, 1859); “Local Intelligence— The Schiller Procession,” The Inquirer (November 9, 1859); “Local Intelligence— Honor to the Memory of a Great German Poet,” The Inquirer (November 10, 1859); “Amusements, etc.—The Schiller Festival,” The Inquirer (November 10, 1859); “Local Affairs —The Centennial Jubilee and Imposing Procession,” Public Ledger (November 10, 1859); “Amusements, etc.—The Schiller Festival,” The Inquirer (November 11, 1859); “Local Affairs—Grand Jubilee,” Public Ledger (November 11, 1859). Classified advertisements in major newspapers provide a detailed picture of the program. For Gustavus Remak, Sr., see Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (ed.), University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics; with Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Founders, Benefactors, Officers and Alumni, vol. 2 (Boston: R. Herndon Company, 1902), 339. 14. “The City Yesterday,” The Inquirer (April 17, 1861), reprinted 30 years later as “The Rebellion,” The Inquirer (April 18, 1892); “City Military Affairs,” The Inquirer (May 27, 1861).

Finding a Place in a New World (1682–1865)

23

15. “Late From The South,” The Inquirer (November 27, 1861); “Late Foreign News—American Tribute to German Sympathy,” The Inquirer (August 9, 1862). Rosengarten, The German Soldier…, 55, 68–71. Other accounts of George Armstrong Custer’s life dispute this account of his ancestry. 16. “German Soldiers,” The Inquirer (April 22, 1885). 17. Rosengarten, The German Soldier…, 74–99; Theodore Griesinger, Frieheit u. Sklaverei unter dem Sternenbanner oder Land u. Leute in Amerika Stuttgart, 1862)/ Rosengarten tried, but with little success, to use the only official source on birth places of soldiers in the Union army, found in the medical statistics of General James B. Fry’s Final Report … of the Operations of the Bureau of the Provost Marshal General of the U.S. (Washington, DC, 1866). Fry was a much decorated officer before becoming Provost General, but in this case, his data fell far short of what was needed. Rosengarten also considered the findings of Benjamin Apthorp Gould, a well-known astronomer who as actuary of the United States Sanitary Commission made a seminal contribution to anthropological statistics by his Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldier, U.S. Sanitary Commission Memoirs, Statistical Volume (New York: 1869). Gould was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln as one of the incorporators of the National Academy of the Sciences in 1863. George C. Comstock, “Biographical Memoir—Benjamin Althorp Gould, 18241896,” and National Academy of Sciences, Volume XVII, Seventh Memoir (1922), 153–80, accessible as: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/ memoir-pdfs/gould-benjamin.pdf. 18. Rosengarten, The German Soldier…, 100–2. 19. For specific units and individual biographies, see The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States 1861-65—Records of the Regiments in the Union Army—Cyclopedia of Battles—Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers, Volume 1 (Madison, WI: Federal Publishing Company, 1908). The section on Pennsylvania was apparently written by David McMurtrie Gregg, a West Point graduate who served with distinction in the war before becoming an important public figure in the state. See also Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861–5, Volumes 1–5 (Harrisburg, PA: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869). For more information on the 74th Infantry Regiment, see http://www.olypen.com/tinkers/74th%20Pennsylvania/ Webpage/default.htm. Despite being frequently described as an all German regiment, Bates’s work shows that recruits of other ethnic backgrounds were in its ranks. For regiments with Germans recruited in Philadelphia, see Frank H. Taylor, Philadelphia in the Civil War, 1861–1865 (Philadelphia: Published by the City, 1913), 96–7. 20. The previously cited sources provide ample information, especially: The Union Army…, 411–12; and Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers…, Volume 2, 915–19 . 21. Bates, Volume 2, 919–20; “Parade of the Seventy-Fifth Regiment,” The Inquirer (January 26, 1864). 22. “Seventy-Fifth Pennsylvania Veteran Vols: Correspondence of the Inquirer,” The Inquirer (September 17, 1864). 23. “Presentation of a Suit of Colors,” The (Philadelphia) Age (September 22, 1865); “The Colors of the Seventy-Fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers,” The

24

Chapter 1

Inquirer (September 22, 1865). Bates concluded his section on the 75th Regiment with the observation: “On the 4th of July, 1866, its tattered banner, carried through all its campaigns, was presented to the Executive for preservation in the archives of the State, and the colors presented by ladies of Philadelphia, before leaving in 1861, were deposited in Independence Hall.” In his detailed account of the celebration of both the end of the war and 90th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence that appeared in The Inquirer, listing veterans from military units throughout the nation, Bates did not mention participation by the Seventy-Fifth Regiment of Pennsylvania. See: “1776. Our Battle Flags. 1866,” The Inquirer (July 5, 1866). 24. Rosengarten, The German Soldier…, 104–14. See also Galusha Pennypacker: America’s Youngest General (Philadelphia: Christopher Sower Company, 1917); “Gen. Galusha Pennypacker,” The New York Times (October 2, 1916). The Pennypacker family may have been more of Dutch ancestry than anything else. In his autobiography, former Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker, a cousin of Galusha Pennypacker, while acknowledging roots in the Netherlands, emphasized the mixed origins of the family. Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker, The Autobiography of A Pennsylvanian (Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Company, 1918), 16–30. John F. Ballier papers, Joseph P. Horner Memorial Library, German Society of Pennsylvania. 25. “Rejoicings in Bremen,” The Inquirer (May 10, 1865); 26. Rosengarten, The German Soldier…, 155–6.

Chapter 2

A More Distant War—and Closer Peace (1866–1871)