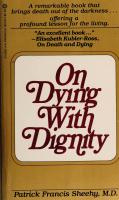

On Dying With Dignity 0523412681, 9780523412689

248 43 241MB

English Pages [260] Year 1981

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

CM

A remarkable book that brings death out of the darkness... offering a profound lesson for the living. “An excellent book...” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, On Death and Dying ■

-

atrick Francis Sheehy, M.D

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/ondyingwithdigniOOOOshee

ADVANCE PRAISE FROM

RESPECTED MEDICAL PROFESSIONALS “I found ON DYING WITH DIGNITY an ex cellent book that has different aspects of special significance for cancer patients, who rarely have the opportunity to read a book of this kind and understand the language at the same time, giving them a sense of control over their own body and a better comprehension of what is happening to them.” •—Elisabeth Kubler-Ross author of On Death and Dying “A stimulating and thought-provoking book . . . using a humane and sensitive and insightful ap proach . . .” —Samuel Achs, M.D. Chairman, American Cancer Society Orange County, California “A straightforward, compassionate and honest book [that] sweeps away much of the medical mystique, jargon, and secretiveness that makes dying a confusing experience . . —E. Mansell Pattison, M.D. Medical College of Georgia 44An exceptional piece of work . . .” —Martin J. Cline, M.D., Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, UCLA

“A sensitive and empathetic discussion of death . . .of benefit to every individual [and] family

sincerely concerned with the process of death [and] the medical profession as well.” —Steven A. Armentrout, M.D. Professor of Medicine University of California, Irvine

“[A] refreshingly honest [guide to] the keys to a peaceful and dignified death . . —Leo J. Steady, Ph.D. Executive Director, Hospice Orange County, California

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND CORPORATIONS PINNACLE Books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchases for educational, business or special promotional use. For further details, please write to: SPECIAL SALES MANAGER, Pinnacle Books, Inc., 1430 Broadway, New York, NY 10018. WRITE FOR OUR FREE CATALOG If there is a Pinnacle Book you want—and you cannot find it locally—it is available from us simply by sending the title and price plus 750 to cover mailing and handling costs to:

Pinnacle Books, Inc. Reader Service Department 1430 Broadway New York, NY 10018 Please allow 6 weeks for delivery. Check here if you want to receive our catalog regularly.

ON DYING WITH DIGNITY Copyright ©1981 by Patrick Francis Sheehy, M.D. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

An original Pinnacle Books edition, published for the first time anywhere. First printing, June 1981

ISBN: 0-523-41268-1 Printed in the United States of America

PINNACLE BOOKS, INC. 1430 Broadway New York, New York 10018

I wish to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Ms. Lori Miller in the writing of this book. She helped crystallize my own thoughts on this subject and translated much of the medical language into comprehensible English. To her, I am grateful. Others who constructively criticized this book were Dr. Arlene Gwon, Dr. Michael Schlutz, Dr. Robert Shapiro, Dr. Joel Manchester, Reverend Bob Perry, Mrs. Lyle Johnson, Mrs. Betty Seitz, Susan O’Halloran, Donald Smallwood, and Tom Murray. To all of the above, I am grateful.

On Dying with Dignity

A young parish priest in Ireland started his sermon by sternly warning his parishioners thus: “Every person in this parish will die—some time.” A little old man in the back of the church began to snigger.

“Every man, woman, and child in this parish will die sometime.” The priest repeated him self loudly in the direction of the little old man. This made the old man laugh hysterically and fall on the floor.

“Why are you laughing?” asked the angered priest. IL

I’m not from this parish at all, Father.”

1

PREFACE Most of us try to avoid the fact that we are going to die until it is upon us. Many of us may pray for a peaceful death, but secretly each of us believes we are the one person who is never going to die. Yes, everybody dies, we tell ourselves, but I just can’t imagine that happening to me! So, when we are stricken with a terminal disease, such as cancer, we feel shocked, angry, and frightened, and react with disbelief. Like most people, we find it extremely difficult to accept our own inevitable death. As a cancer specialist, I care for many patients who must face the fact that they are dying. Early in my career, I realized that my job included di agnosing and treating patients with terminal can cer, who would die within a few months or years At the time of diagnosis, the quality of the lives

of many of these patients differed greatly from each other. However, they all had in common, the desperate desire to live, in spite of the limited time most of them knew they had. As time passed, it became obvious to most of them that the treatments I had been giving them were fail ing. Still, most could not accept the inevitability of death. If I tried to talk to them about their deaths, they ignored me; they avoided any tactful suggestions I tried to make about how they could manage their own deaths. They were shocked if I gave them facts straight out. No matter how I tried to talk about their deaths, most of them avoided the subject. They wanted only to concen trate on anything I might try, any desperate at tempt to save their lives. They would not give up, could not accept that they were going to die. The more I saw of this kind of behavior, the more amazed I was. People learn to accept many things in life; they will live with defeat, pain, fail ure, depression, and rejection. Yet most cannot accept death. It is the most difficult of all the ex periences we must face in life. For a long time, I thought it was natural, and human, to fight the idea of one’s own death in body and soul until death’s grim reaper had done its part. But once in a great while, like a fresh breeze on a hot and humid day, a patient would come along who could accept the fact that he or she was dying, without the usual fear, anguish, and resistance. During my first three years in practice, I had

the opportunity to observe a limited number of these patients, who, for many reasons, I thought died with great dignity. When I went back to re view their charts, I found that all of these unique patients had something in common. And based upon what I found, I began to educate more of my patients about the dying process. This book is an expansion of what I developed to assist ter minal patients, their family, and friends in ac cepting death’s inevitability. Although some significant research has been done in recent years on the dying process (most notably the work of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross), I feel most people still do not understand the nat ural and sometimes quite satisfying stages a per son, facing his or her own death, experiences. This book is designed to explain exactly what happens, or can happen—from the stages of physical de generation through the emotional crises—-and I hope will provide the reader with a greater under standing of what is now fearfully regarded as “the mystery of death.”

CHAPTER I

THE PHENOMENON OF DEATH The aim of this book is to educate healthy peo ple about the dying process; specifically, to dem onstrate that death can be experienced with ease and does not have to be the terrifying event it has traditionally been conceived to be. While it is difficult to determine the source of our fear of dying, most cultures throughout the history of mankind have developed myths and ta boos to try to explain away its terrifying reality. Many cultures have tried to ignore death entirely because it represented the antithesis to life. In the twentieth century, however, both scientific and metaphysical ground has been broken regarding the death experience in Western civilization. Peo ple have finally begun to be curious about what really happens when we die, and have found the courage and maturity to begin to realistically ex-

5

amine death without fleeing in panic to supersti tion or primitive religious beliefs. In part, I be lieve man’s struggle to avoid the reality of death is based on his deep-rooted feeling of immortal ity. There is, in other words, a deep-seated feeling in the heart of each of us that we are, indeed, going to live forever. We have struggled for centu ries with this essential paradox. Scientific research in the twentieth century has allowed many people to examine death realisti cally. Researchers have begun to conquer their own fears of death and have begun to estabfish an objective record of the death process. Having ac cepted the aging process and death as a natural biological process, the researchers can now help all of us handle death in a more sophisticated and enlightened way. Death comes in different ways to different people. For some, it arrives suddenly. Accidents and fulminant diseases leave the victims shocked, unprepared, and stunned. In these cases, there can be no real preparation, for the lives of their victims are over almost as soon as the disease strikes or the accident happens. This book does not address itself to such sud den deaths. Rather, it addresses men and women whose dying process will span a prolonged period of time, men and women who accept that every one ages and dies in time, especially those who will have advance knowledge of their own deaths, those who have contracted fatal illnesses, such as 9

malignant cancer, or the degenerative diseases of the heart, brain, kidney, or lung. It is especially, for those who would like to develop the art of dying well; those who are living with, loving, and supporting a family member or friend who is going through the dying process, and who must con tinue to live on with the loss. For those who have lost someone dear to them, this book may relieve the anguish or guilt they experienced because the death process was not understood. While the sub ject of death remains uncomfortable for most, this book will describe how some patients— ordinary people—managed the dying process with full knowledge of what was happening and died with courage and dignity. The current state of the art of medicine has made it more and more feasible for a physician to approximate the expected time of death for a ter minal patient. Indeed, with practice, experience, . and a willingness to learn from past incorrect es timates, it is possible to become increasingly ac curate in predicting the approximate time of the death of a patient. As a physician, I feel strongly that patients deserve to know that they have con tracted a fatal disease and when they can expect to die. This information should be given to the patient as soon as the physician feels secure in his ability to give it to him. Many of my colleagues in medicine disagree with this practice. Many doctors believe that peo ple live happier and more relaxed lives if they are

not aware that they harbor degenerating diseases that wiH ultimately and predictably take their lives. As long as their patients are without overt symptoms, these physicians feel they are doing their patients a favor by letting them just continue to live as they always have. Perhaps the most important point in this book, which will become clear in later chapters, is that it is unfair and inhuman for a physician to let a patient die without his or her having been told the facts of the matter. Man is an intellectual and sensitive being, and this presupposes his ability to organize, execute, and achieve states of being that will bring satisfaction. People need to feel they have a dignity and a purpose in life. Telling a patient he or she is going to die gives that per son a choice. He can choose, and has the right to choose, to end his life with dignity. With the knowledge that he has limited time left on this planet, the person can organize his last days and complete “unfinished business.” Only with this knowledge of his own death, and its approximate time, can the person find the courage to execute his final wishes and thus achieve peace and satis faction. In my private practice of medical oncology, I have noted the ease, tranquility and grace with which some of patients die. I have also seen pa tients who die feeling indignant, in pain and mis erably. Having seen many people die, I have dis covered that there is an art to dying well.

8

Those who died with dignity had two basic things in common. First, they had an intellectual . understanding of how the body works when it is healthy and what happens to it as it begins to de generate. With this knowledge, they were able to conquer their initially overwhelming fear of death, since they discovered that many of their fears were unfounded. Fear of death is based on ignorance, and can be overcome once the physi cal facts of death are understood. This book will present all of the basic information necessary to an understanding of how the body functions when it is healthy, and what happens when it contracts a fatal illness. Second, those who died with dignity had in common the ability to let their minds go through the necessary responses to their deaths. In every terminal patient, the body becomes disease one oeio is in any way af fected. So naturally the healthy mind rejects the information that it is living in a degenerating body. The mind’s very existence and health re quire that it deny that the body is dying. This is dying. Their minds become so programmed to denying the facts. However, once the mind is con vinced that it is living in a diseased body, several things happen. First, the mind rears up in revenge and anger, asking why and wherefore and who the heiTdfd this. It must be allowed its indignation and dismay. It is only natural. It is being cut off

from life through no fault of its own. It becomes angry with itself, angry at the world, and angry at the plight of mankind. Once the mind has been allowed its revolt, its anger, and its desperate at tempts to think of a way to survive, it becomes depressed, resigned, and then philosophical. From thiss point, the mind can move either rap idly or slowly into the final and most peaceful stage of dying, that of acceptance. When the mind can accept that death is inevitable, there follows a sort of tranquility unique in human ex perience. This is the essence of a peaceful death. Once the mind has become accepting and tran quil, dying patients have the freedom of honest emotional expression. They can use the time left Co them to complete^ their worldly affairs, to dis mantle their financial obligations, and to be with the people who have been important to them. They are free to look back over their lives and to relive the joyous moments of sharing and love. They are free to rid themselves of any remorse or guilt they feel. They are free to die in peace. As you read this book, many people are dying in hospitals, but these people are thinking that in a month, or perhaps even less time, things will be back to normal and they will be up and about again. Their physicians and their families know that they will be dead. But withholding this information is legal because it is done in the name of compassion. The healthy despise and fear death, and because of this make unwilling fools of those

10

who are dying by denying them the right to knowledge that would allow them to choose to die in peace and with dignity. A physician does not have the right to allow a man to die unless the physician has first informed him of his lot, yet many physicians do not inform their dying patients. They say the information will only make things more difficult for the pa tient and will hurt him. But what they really mean is that they do not want to be confronted with the pain. Relatives, close friends, and mothers and fathers of dying patients make simi lar decisions for the dying, and their motives are usually the same as the physicians’: fear of the pain they will feel if they tell the patient he is dying. Hence, a foul and treacherous conspiracy gets set up. These loved ones do not realize that death is not necessarily terrifying to a terminally ill patient. Death is the final peace, but peace can be reached before death actually occurs if the patient is given the opportunity to complete his life in the manner he so chooses. It is also important to realize that a human being cannot leave this world without being missed by someone, be it a mother, a father, a friend, even an enemy. Once a person who is dying finds within himself the courage to accept his death, he wants these imporant people in his life to listen to and accept whatever he needs to say to them. He can do a lot to relieve the pain and grief of those he is leaving behind. Once 11

death has been accepted, he will be far more con cerned about what will happen to his family when he is gone. The more knowledgeable he is about what they will be experiencing, the more con cerned for others he will become. This is part of the responsibility of dying. People who die with out being offered the opportunity to take respon sibility for their own lives cannot possibly die with dignity. Not only do humans have the right to plan the manner in which they will die, but, because of their natural desire to prepare those who they will leave behind, it is a necessity for them to do so. A responsible death is a dignified one. And for many, responsibility comes only with knowledge of their own dying process. When I first started practicing medicine, like many of my colleagues, I wanted to flee as fast as possible from dying patients. I would not accept patients who had far-advanced malignancies sim ply because I knew there was nothing I could do to prolong their lives. But as time went on, and I saw numbers of people die in anguish, I decided to embrace these patients with more warmth and understanding. This decision came about because of an experience with one young patient who managed her own death with amazing courage and dignity. It was her death that stimulated me to help the rest of my patients to try to control their dying as they controlled their lives. The more human beings know about themselves and

12

their environment, the better they are able to control their own destinies. This is true for both the living and the dying. It was Susan’s death that opened my eyes to the possibility that people could embrace death with confidence, integrity, and peace. Susan was 26 and working as a receptionist. When she first came to me, she had shiny black hair and was tall and slim, perhaps even a bit too thin, and had a pleasant manner and an easy disposition, which helped her make friends quickly. One evening, she was sitting reading a novel at her reception desk when she felt a sharp pain in her back. The pain was quite severe, but it lasted only a few seconds. Naturally, she was frightened by it, and thinking it was a muscle spasm, she im mediately put her book down, got up from her desk, and pressing the back of her hand against the muscles over the painful area, she began to walk. Gradually, the pain went away, so she sat down and began to read again. About two months later, she again experienced a sharp, shooting back pain. This time, the pain awoke her from a dream. In the dream, she was being stabbed by a sharp knife. She awoke, frightened, and in her semi-somnolence realized that she’d been dreaming but that the pain was very real. It was concentrated on the left part of her lower back and lasted longer this time. She slowly got out of bed and found that pushing the back of her hand against the muscles over the r

13

source of the pain eased it. Again, she started to walk, but this time the pain was so severe that sweat formed on her forehead. This made her more frightened. As she was wondering whether she should call her parents, the pain slowly began to subside and she was able to get back into bed. As it gradually disappeared, she fell back into a deep sleep. The next morning when Susan awoke, she re membered the pain and the memory terrified her. She decided, however, that it had not lasted long, and that it was probably just a muscle spasm. She said nothing to her parents or her friends at work about it. At this time, Susan was also taking a course in human physiology, in preparation for a career as a physiotherapist or nutritionist. As she studied, she became interested in the workings of the heart, the lungs, and the kidneys, and ultimately in the whole of human physiology. Although she did not have a detailed knowledge of how the dif ferent systems of the body function, she retained a clear conceptual understanding of how the body works. This knowledge, I believe, was of great help to her when she became ill. One evening while playing racquetball with her latest boyfriend, Susan again experienced a sharp pain in her lower back. This time it lasted longer than ever before, and was so severe that she had to fall to the ground to ease it. She was taken to the emergency room.

Susan was carefully examined, and multiple blood tests were done and X-rays taken. Al though she continued to experience sharp pain, no obvious cause could be found. She was given Demerol to control the pain and was admitted to the hospital. The surgeon who saw her that night could not diagnose the condition either, so he de cided to keep her hospitalized to observe her progress. During the next two days, the pain got worse, even though she was taking large doses of medi cation. On the fifth day in the hospital, the sur geon thought he felt a mass on the left side of her upper abdomen, which made him suspect she had a tumor. Nervously, the surgeon operated and found a small tumor attached to the adrenal gland on her left side. Although gross inspection led him to believe it was not malignant, he re moved it anyway, since it was abnormal. Upon closer inspection of a frozen section re moved during surgery, it was found that Susan had a malignant tumor in the adrenal gland. At the time of the operation, the surgeon carefully inspected her kidneys, lymph nodes, and liver, as well as the area around the backbone, but he had been unable to find any evidence that the tumor had spread from its primary site. Susan spent the next week recovering from surgery. She was told that a cancerous tumor had been found and re moved and that the surgeon believed that all of the cancerous cells had been eliminated.

15

Susan went back to work, and returned to her normal life. As time passed, though, she began to notice that she became short of breath whenever she exercised. Unsure of what the trouble might be, she went back to her physician for an exami nation. He found nothing wrong. She returned to work, believing her illness was psychosomatic, and for two months she pushed herself and exer cised harder and harder. But as she did this, she began to feel worse than ever. This time, Susan decided to see a different physician. He found that her liver was enlarged and he hospitalized her to evaluate the condition and locate the cause. A liver scan revealed that Susan had multiple liver defects, suggesting that her tumor had recurred. It was at this time that I was consulted. When I first entered Susan’s hospital room, I think she sensed my apprehension, but nonethe less she greeted me cheerfully. “Oh, come in, Doctor,” she exclaimed with a smile. “I believe I have a problem you might help me with!” “Yes,” I said, “I believe you do have a prob lem.” “Take a seat and let’s talk about it” was her practical reply. I sat down and took notes as Susan told me her medical history. Because of her work at the ath letic club and her knowledge of human physiol ogy, she had no trouble understanding as I ex-

16

plained what happens when the liver becomes damaged. I explained that a functioning liver is essential to life, and the necessity of chemother apy treatments to attempt to control the tumor. She agreed to the treatments, although she was well aware that the side effects would include loss of her hair and nauseousness at times. She hoped, as I did, that the treatment would cause a remission and rid her body of the potentially fatal growth. From the very beginning, Susan insisted on knowing what her prognosis was. I made it clear to her that it appeared she had a particularly ag gressive tumor and that it might, in fact, be diffi cult to control with chemotherapy. I also told her that her condition was not hopeless and that peo ple had experienced remissions with it. Susan initially responded to this information with fear. Her expression became very serious, the smile left her face, and her jaw dropped slightly, making her face look quite forlorn. “No one knows when someone is going to die,” I tried to reassure her, “and no one knows exactly what any one person will have to suffer before he reaches that point. My present plan is to treat the cancer as aggressively as possible in order to keep the tumor controlled. If the tumor progresses in spite of the treatment, you will be told so. ” I promised her I would be totally honest with * her at all times. With chemotherapy treatments, we controlled the tumor’s potential threat for 17

nine months. Then, however, the tumor became resistant to the drugs being used, and despite all our attempts (including one or two of the newer, experimental drugs), the tumor began to expand

One day, Susan came to my office on an un scheduled visit. “Doctor, I believe I am dying, she stated flatly. “I have the feeling this tumor is slowly taking over my body. Please tell me frankly what my chances are.” I sat down with her, and she stared me in the face intensely. “Susan,” I said, “it is true that your liver is get ting larger and it is also true that the drugs we have been giving you have failed to control your tumor. It is probable that it is in the process of destroying your liver. I do not know of any treat ment that would work for you, but if you want another opinion, I would be happy to have an other oncologist examine you. Sometimes it is good to have a fresh look at a problem.” She gave me a straight, serious look and said, “Dr. Sheehy, I believe in you. I believe you would refer me to some other clinic if you thought there was a chance I could be cured there. I will do whatever you say.” Taking a deep breath, I told Susan that I had discussed her case with special ists in both New York and Los Angeles, and that none of them had anything more to offer than I had. “I feel we should stop trying,” I said quietly, “and let you enjoy whatever time you have left 99

18

here without experiencing the distressing side effects of the drugs.” Susan was completely quiet for a moment. She stared thoughtfully at the floor, and then looked up at me. “Tell me how I am going to die and what it will be like.” At this point, I hospitalized Susan again so I could find out exactly how far her tumor had spread. At the end of my evaluation, I went to her room. “Susan, your tumor has progressed even further than I thought.” She stared at the ceiling, and then calmly said, “I am going to die very soon, aren’t I?” “Yes, Susan, I believe you are going to die in the not-too-distant future.” The magnitude of this girl’s tragedy struck me as I uttered these words. My voice quivered with poorly controlled emo tion as I realized Susan was indeed going to be destroyed by the malignant tumor very soon. • “Dr. Sheehy,” Susan said, “I understand a lot of things. I know more than you think I do. I do not believe in miracles or quack treatments. And I believe we cannot know really if death does or does not have a purpose.” She hesitated then, looked me in the eyes, and continued, “But I want my death to be a dignified one.” I was struck by her courage, and asked her to tell me exactly how she wanted to die. “I want to be conscious for as long as I can, she said. “I want to be free from pain for as long as I can, and when the pain becomes so severe

19

that life is only misery and suffering and I am un able to express love or gratitude, I want you to give me something to take my life.” I moved closer and held her trembling hand. “Susan, in your case the pain will not become so severe that you won’t be able to stand it. This will not happen. Now let me tell you what it will be like. The tumor will slowly grow and will grad ually destroy your liver. During this time, you may feel tired or weak even when you are lying in bed. You will feel lethargic, without much pep, and perhaps your mouth will feel dry. As the de struction of your liver progresses, you will be come sleepier and sleepier, and finally you will sink quietly into a coma. There will be very little pain. Given the rapid growth of your tumor in the recent past, it will probably not take a long time for this process to occur.” “I am glad you have told me this, Doctor. I believe I can face it more easily now. I do want to be with my family for as long as possible, and I want you to explain to my family exactly what is going to happen to me so that they will better un derstand and be able to take care of me. I want this to be a dignified event.” I walked out of Susan’s room and immediately spoke to her parents. I explained to her father, a local businessman, her mother, a teacher at one of the local schools, and her two brothers and sis ter exactly what was going to happen to Susan. They listened in awed silence. At first, they were

20

not certain they had understood. No one accepts the news of impending disaster easily. Their youngest daughter, the beautiful flesh of their flesh, was going to die, and she wanted her death to be a dignified event. It was very difficult for them to understand. I explained that Susan had made it clear there was to be no more time spent searching for new cures or hoping for miracles. Her remaining time was to be for togetherness*

ture. I explained to her parents that although Su san had requested it, I could do nothing to take the girl’s life. The aim of my treatment from here on would simply be to keep her comfortable. Susan lived longer than I expected. For the next two months, she was able to be up and about and socializing with friends. Initially, no one out side her family knew her condition was terminal, but as time passed she informed all the people she cared about. Her family took her for a week’s va cation. She sat in the sun and talked with them for long, enjoyable hours. They talked about the things they had done together in the past, they talked about the good times and the bad, about what Susan was like as a little girl and what she did that was foolish and funny. And finally, they talked about what it would be like for each of them when she was no longer with them. That part was difficult. She would be missed. Her death would leave a void. Her mother cried. But

21

Susan was calm and tearless, and full of gratitude for each day as she lived it. Susan actually took it on herself to tell her par ents how she felt it would be best for them to be have in the coming months. She explained that her death would be tough on them, but that she knew they had the strength to get by, that all men and women had. She asked her brothers and sister to help her parents through the difficult times, to help them through the grieving. And when the time came, each of them felt a special love and respect for Susan that allowed them to really help. When they returned from vacation, Susan spent a period of time at home with her family. I did not see her much during this time. One evening, however, she called me and said, “I am now ready to go into the hospital and die.” “Susan, how do you know you are dying now, and why do you want to die in the hospital? Why not stay home?” “I feel weak and tired. I feel the end is near. I feel my parents are not capable of taking care of me any longer at home, and I do not feel secure there. There is too much sorrow. Mother is al ways crying and I do not feel sad. Most of all, I need to be alone now for a while, and my family just doesn’t seem able to let me be. I want to go into the hospital and have time to be alone.” When I saw Susan in the hospital shortly after her call, she looked much worse. But she also looked s erene.

22

“You know,” she said, “dying is a lonely event even in the midst of the people you love the most. You must have time for yourself. You must have time to think about yourself and your life, and time also to think about those around you and those behind you.” She paused. “There is only so much time,” she said. “You must prepare your friends and your family for your own death. I have done all of these things, and I am satisfied. Now I am tired and I want to be alone. I am not sad. I simply am tired.” * I had never seen anyone handle death with such grace and dignity. And although I had read many books about death and dying and about the various problems patients go through, I still could not understand how Susan could handle her death with such grace. I wondered what her secret was. For the next two weeks, Susan became more and more sleepy. Finally, she went into a coma. Initially she responded to her family, but as time passed and the harmful chemicals accumulated in her blood, she responded to nothing worldly at all. She remained in a coma for seven days, and then died. It was perhaps the most peaceful and well managed death I had ever witnessed. It urged me to discover the special insight she had that allowed her to handle her death with such calm and without terrifying those around her. As I examined Susan’s chart and spoke to her family and friends, I gathered a portrait of a II"

---------I— I I

■■■HI

l|1' '■***

'SL—

r

z

23

rather ordinary young American woman. She had planned to marry and have a family. It was im portant to her to be a good mother. She had fallen in love a few times in her short life, and had been hurt when the relationships broke off, but was optimistic about her future. Her primary goal was to be a loving and supportive wife and mother. She was not especially emotional, and ev erybody remembered her as a cheerful, some times silly girl, whose most extraordinary act in her life was her death. During the next four years, I watched other Sus ans carefully, others who were able to manage their deaths with dignity. There was a young man dying of bone cancer, then another young man who was dying of Ewing’s sarcoma, a middleaged lady who died of breast cancer, and a middle-aged man who died of lung cancer. Fi nally, a pattern began to emerge. I had found the secret to Susan’s ability, and it is that secret I want to share. All of us are going to die and,. OS going to need help. It is not easy. It demands a clear understanding of what is happening, the courage to accept the inevitable, and the integrity to mamtain self-control. Most people die poorly. Their deaths are a farce, made so by customs, cultures, physicians, and families. Most terminal patients believe they will soon be well, and be cause they are not told the truth about their con dition, they are not able to face death. The real 24

sting is ignorance. Victory can be achieved only when that ignorance is changed to knowledge. As I said earlier, the patients I have seen who die with digi they clearly their bodies. The physical process of their disease was hot a mystery to them. Second, all of these patients found within them the ability to cope with their anxieties and fears,and to understand what was happening to their minds. To these two common factors I will now add a third, made clear in the case of Susan’s death. The patients understand what their passing means both to themselves ah eir es and friends which allows them to take responsibility for their deaths by helping those they leave behind to sur vive without them. First, I will address the common fears of dying and explain how they can to a large extent be al leviated. I will then explain how the human body functions normally, and what disease does to it. Although I realize some people may not wish to become experts in human anatomy, it is my fer vent belief that knowledge of how the body func tions normally and abnormally will allow the reader to begin to replace ignorance with under standing. He will then be prepared to discover how people die. Finally, I will give examples from my own experience to demonstrate why it is necessary for the dying to teach those they leave behind how to survive without them. Dying is a inr-IM

I

iiimibi

r-»

-* riaagfeaai 1 ~

tji

i< i

-

-—a—

--

. . -

/

25

-

■.

![Living With Dying [1 ed.]

9780232528541](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/living-with-dying-1nbsped-9780232528541.jpg)