Mothers of Invention: Feminist Authors and Experimental Fiction in France and Quebec 9780773570269

Mothers of Invention draws together innovative works of fiction written by French and Quebec feminists in the mid-1970s.

213 6 22MB

English Pages 384 [365] Year 2002

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Illustrations

Introduction

1 History, Ideology, Theory: Tracing the Contexts of Feminist Writing in the 1970s in France and Quebec

The Revival of Feminism in France and Quebec

The Question of a New Writing by/for Women

Hélène Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brassard, and Jeanne Hyvrard: Four "Mothers of Invention"

Feminist Writers and Avant-Garde Practice

2 (W)Rites of Passage: Hélène Cixous's La

Points of Departure

Bringing Language to (De)Light

3 Excavating the Body, Unwinding the (Inter)Text: Madeleine Gagnon's Lueur

Maternal Archaeographies: Writing the Body's Will and Legacy

Her Daring Paradigms: Hybridized Genres, Subversive Syntax, and Innovative Intertextualities

4 Drawing the Line and Transgressing Limits: Nicole Brossard's L'Amèr

The Lesbian Subject as Writer: Again(st) the Mother

The Problematics of Genre and Its Links with Gender

5 Madwomen and the Mother Tongue: Jeanne Hyvrard's Early Novels

Of Madness and the (M)other

The Refusal of Language and the Language of Refusal

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Citation preview

Mothers of Invention Feminist Authors and Experimental Fiction in France and Quebec

Mothers of Invention draws together innovative works of fiction written by French and Quebec feminists in the mid-1970s. Through an analysis of the strategies adopted by Helene Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brossard, and Jeanne Hyvrard as they rework maternal and (pro)creative metaphors and play with language and conventions of genre, Milena Santoro identifies a transatlantic community of women writers who share a subversive aesthetic that participates in, even as it transforms, the tradition of the avant-garde in twentieth-century literature. Santoro elucidates notoriously difficult works by the four "mothers of invention" studied - Cixous and Hyvrard from France, and Gagnon and Brossard from Quebec - showing how the rethinking of images associated with feminity and motherhood, a disruptive approach to language, and a subversive relation to novelistic conventions characterize these writers' search for a writing that will best express women's desires and dreams. Mothers of Invention situates such ideologically motivated textual practices within the avant-garde tradition, even as it suggests how women's experimental writings collectively transform our understanding of that tradition. Santoro makes clear the shared ethical and aesthetic commitments that nourished a transatlantic community whose contribution to mainstream literature and cultural productions, including postmodernism, is still being felt today. MILENA SANTORO is assistant professor of French at Georgetown University.

This page intentionally left blank

Mothers of Invention Feminist Authors and Experimental Fiction in France and Quebec MILENA SANTORO

McGill-Queen's University Press Montreal & Kingston • London • Ithaca

McGill-Queen's University Press 2002 ISBN 0-7735-2373-1 Legal deposit third quarter 2002 Bibliotheque nationale du Quebec Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free, and printed with vegetablebased, low voc inks. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Funding has also been provided by the International Council for Canadian Studies through its Publishing Fund and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University. McGill-Queen's University Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for its publishing activities. We also acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Santoro, Milena Mothers of invention: feminist authors and experimental fiction in France and Quebec Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7735-2373-1 1. Feminist fiction, Canadian (French) - History and criticism. 2. Feminist fiction, French - History and criticism. 3. Experimental fiction, Canadian (French) History and criticism. 4. Experimentalfiction,French History and criticism. 5. Canadian fiction (French) Women authors - History and criticism. 6. French fiction - Women authors - History and criticism. 7. Canadian fiction (French) - 20th century - History and criticism. 8. Canadian fiction (French) - Quebec (Province) - History and criticism. 9. French fiction 2oth century - History and criticism, 1. Title. PQ149.S25 2002 0843.54'99287 c2001-904132-2 Typeset in Palatino 10/12 by Caractera inc., Quebec City

To the many inspiring "mothers of invention" I have known but most especially to my own, most beloved mother, Rolande

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Illustrations xiii Introduction 3 1 History, Ideology, Theory: Tracing the Contexts of Feminist Writing in the 1970s in France and Quebec 10 The Revival of Feminism in France and Quebec 10 The Question of a New Writing by/for Women 15 Helene Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brassard, and Jeanne Hyvrard: Four "Mothers of Invention" 23 Feminist Writers and Avant-Garde Practice 30 2 (W)Rites of Passage: Helene Cixous's La 37 Points of Departure 41 Bringing Language to (De)Light 76 3 Excavating the Body, Unwinding the (Inter)Text: Madeleine Gagnon's Lueur 98 Maternal Archaeographies: Writing the Body's Will and Legacy 104 Her Daring Paradigms: Hybridized Genres, Subversive Syntax, and Innovative Intertextualities 129

viii Contents 4 Drawing the Line and Transgressing Limits: Nicole Brossard's L'Amer 153 The Lesbian Subject as Writer: Again(st) the Mother 162 The Problematics of Genre and Its Links with Gender 185 5 Madwomen and the Mother Tongue: Jeanne Hyvrard's Early Novels 208 Of Madness and the (M)other 212 The Refusal of Language and the Language of Refusal 246 Conclusion

268

Notes 283 Bibliography Index 337

319

Acknowledgments

The research for this book was completed in part with funding assistance from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and from Princeton University and, more recently, with support from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Georgetown University, whose Summer and Junior Research Grants were invaluable in allowing me to bring this project to completion. I am also indebted to the editorial staff of McGill-Queen's University Press for their deft and expedient shaping of the manuscript into book form and for their assistance in obtaining publication subventions. I would like to express my deep gratitude to the four authors whose works I study here: Helene Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brossard, and Jeanne Hyvrard. All have given generously of their time to answer my questions both in person and in writing, and have offered me sustained encouragement in the course of my work in the form of intellectual guidance, copies of their works (published and unpublished), or access to their archived materials. It is a great privilege to study the writings of women who are as inspiring in their mentoring and friendships as they are in their word craft. Over the ten years that I have been working on this project, I have been most grateful for the intellectual and personal support of Karen McPherson, an extraordinary adviser but an even better friend. I have also been blessed by Rene Lapierre's constant presence in defiance of all distances; his intellectual rigour, gentle guidance, and confidence in me have meant more than words can say for the progress of this book and its author.

x Acknowledgments Many others have accompanied and encouraged me over the course of this project, giving of their humour, their understanding, and their experience. My parents, Bruce and Rolande Andrews, are first among these, for they always manage to find the right words, creative thinking, and healthy laughter to see me through. My thanks also go to, in alphabetical order, Margaret and David Boyes, Cynthia Cupples, Louise Dupre, Barbara Havercroft, Anne and Uwe Hollerbach, Cathy Saunders, and of course, my husband, Robert Santoro, whose patience and love I treasure always. The author gratefully acknowledges permission to use material previously published in the following edited volumes: "Feminist Translation: Writing and Transmission among Women in Nicole Brossard's Le Desert mauve and Madeleine Gagnon's Lueur," in Women by Women: The Treatment of Female Characters by Women Writers of Fiction in Quebec since 1980, edited by Roseanna Lewis Dufault (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997): 147-68; and "Eblouissements: La portee des rencontres artistiques dans La," in Helene Cixous, croisees d'une ceuvre, edited by Mireille Calle-Gruber (Paris: Editions Galilee, 2000): 153-62. Poetry excerpts from Nicole Brossard's "Suite logique" in Le Centre blanc (©1978 Editions de 1'Hexagone) and from Madeleine Gagnon's Pensees du poeme (© 1983 VLB editeur and Madeleine Gagnon) are reproduced by permission.

Abbreviations

Ai Madeleine Gagnon, Autographie 1 A2 Madeleine Gagnon, Autographic 2 AL Nicole Brossard, The Aerial Letter L'Amer Nicole Brossard, L'Amèr ou le chapitre effritè Budge E.A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead CTW Helene Cixous, Coming to Writing and Other Essays Encore Jacques Lacan, Le Sèminaire de Jacques Lacan, Livre xx: Encore Feminine Jacques Lacan, Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and Sexuality the ecole freudienne HCPW Morag Shiach, Hèlène Cixous: A Politics of Writing HCR Helene Cixous, The Hèlène Cixous Reader HCWF Verena Conley, Hèlène Cixous: Writing the Feminine JN Hèlène Cixous, "Sorties" from La Jeune nee Laugh Helene Cixous, "The Laugh of the Medusa" LLA Nicole Brossard, La Lettre aèrienne LM Jeanne Hyvrard, La Meurtritude

xii Abbreviations

Lr Madeleine Gagnon, Lueur LV Alice Parker, Liminal Visions of Nicole Brossard MD Jeanne Hyvrard, Mother Death MM Jeanne Hyvrard, Mere la mort NEW Hèlène Cixous, The Newly Born Woman PC Jeanne Hyvrard, La Pensee corps PdeC Jeanne Hyvrard, Les Prunes de Cythère PPR Charles Russell, Poets, Prophets and Revolutionaries Rire Helene Cixous, "Le Rire de la Meduse" si Susan Suleiman, Subversive Intent Souv. Sigmund Freud, Un Souvenir d'enfance de Leonard de Vinci sv Louise Dupre, Strategies du vertige TAG Richard Murphy, Theorizing the Avant-Garde TOM Nicole Brossard, These Our Mothers, Or: The Disintegrating Chapter Venue Helene Cixous et al., La Venue a I'ecriture WF Karen Gould, Writing in the Feminine

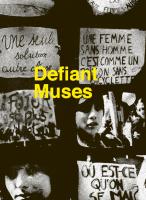

1 The Nightmare, 1781. Henry Fuseli Founders Society purchase with funds from Mr and Mrs Bert L. Smokier and Mr and Mrs Lawrence A. Fleischman. Photograph ©2000 The Detroit Institute of Arts.

2 Cover of Hèlène Cixous's Souffles (1975) ©1975. Reprinted with permission of Editions des femmes.

3

The Prisoner's Dream, 1836 [Der Traum des Gefangenen].

Moritz von Schwind

Inv. Nr. 11565. Bayerische Staatsgemadesammlungen, Schack-Galerie, Munich.

AERIAL VISION The SPIRAL'S sequences in its energy and movement towards a female culture

c. Work done on the imaginary, language, thought, and knowledge Dangerous zone: madness, delirium, or genius d. Radical feminism, political, economic, cultural, social, ecological, and technological feminism

Women's invisibility The great darkness

a. New sense within Sense e.g. The Second Sex Three Guineas

d. Questing sense, born of the conquest of non-sense e. Sense renewed, through excursions into and explorations of non-sense f. New perspectives: new configurations of womanas-being-in-lhe-world of what's real, of reality, and of fiction

b. New sense in movement within Sense e.g. Feminism from the Sixties to the Eighties: bookstores, theatres, music, books, films, demonstrations, etc.

Female culture, whose existence essentially depends on our incursions into the territory until today held by non-sense. Without sequences 5 and 6, the spiral, repressed in the borderlines of sense, would end up closing in on itself.

4 "Aerial Vision," by Nicole Brossard Reprinted with permission of the Women's Press from The Aerial Letter, by Nicole Brossard, translated by Marlene Wildeman. ©1988. www.womenpress.ca.

Mothers of Invention

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction Pendant qu'un certain fèminisme prend sa bouderie et son isolement pour de la contestation et peut-etre meme de la dissidence, une veritable innovation feminine (dans quelque champ social que ce soit) n'est pas possible avant que soient eclaires la maternite, la creation feminine et le rapport entre elles.

[While a certain feminism continues to mistake its own sulking isolation for political protest or even dissidence, real female innovation (in whatever social field) will only come about when maternity, female creation, and the link between them are better understood.] Julia Kristeva1

Julia Kristeva, along with her contemporaries Helene Cixous and Luce Irigaray, is often mentioned as one of the defining thinkers of what North American literary critics have called "French feminism." And yet as the above excerpt from a 1977 Tel Quel essay shows, even at this fairly early juncture in contemporary French feminist activism, Kristeva is at pains to distance herself from "a certain feminism," already negatively connoted because it does not practise the forms of dissidence and innovation that she so clearly valorizes both in this essay and elsewhere in her important body of critical work. In the current period of considerable anti-feminist backlash and ebbing commitment to feminist activism, which make some women nostalgic for what they perceive as the movement's halcyon days, it seems salutary to look back at this earlier critical moment and recall how conflicted the terrain of feminist thought has always been historically, both in the international forum2 and within its culturally specific manifestations. Indeed, conflicts have been one of the greatest sources of vitality in feminist thinking, and they have led to a greater understanding and tolerance of differences among women which are essential to the ethical objectives at the heart of the movement. In the French context, given the substantial differences among those who have been called - and have often denied being - "French feminists," I must therefore wholeheartedly agree with critics such as Lynne Huffer when she suggests that since "the concept [of French feminism] no longer works ... it is time to move on."3

4 Mothers of Invention

While it seems clear that moving on from a reductive view of French feminism's major figures and consequential texts is both a timely and a necessary gesture, I am not convinced that this can be done solely through the kind of comparative theoretical and philosophical critique so often undertaken by American feminist scholars, of which Huffer's Maternal Pasts, Feminist Futures is an impressive recent example. By contrast, the way I choose to move beyond the French feminist cliches nourished by so many blanket statements about women's texts of the 19705 is to examine the writing practices that women were really exploring, how they were doing so, and in what context. While the debates over essentialism, difference, or the ineluctable conservatism of nostalgic notions of the mother as origin (effectively argued by Huffer) are indeed important, I prefer to combat the reification of certain figures and the conceptual stances imputed to them by sidestepping these seemingly endless theoretical skirmishes to focus, rather, on what they have often occulted or even completely ignored: the prodigiously creative and fascinating fiction written by the very women who were caught up in what was arguably feminism's finest moment. It is my desire and purpose that we not forget the extent to which creative writing fuelled and complemented the gestation of feminist theory in French. In addition, I believe a persuasive case can be made that dissidence and innovation do in fact characterize what many women were publishing during this period, and that, moreover, there was a definite community of thought and a shared set of strategies among women writing in French both within and outside France. It is significant that in her move to work around one of the central impasses she has noted in current feminist theory, Huffer finds support and a fresh perspective in the writings of Quebec author Nicole Brossard. Like many of her readers, I too have been inspired by Brossard's writings ever since I first encountered her best-known experimental novel, Le Desert mauve, in 1990. In fact, it was my readings of Quebec women authors that sparked my desire to explore French feminist thought, since it seemed unquestionable that these francophone women's works were influenced by those of French theorists such as Cixous and Irigaray, in addition to Jacques Derrida and Jacques Lacan. What the ensuing research revealed, of course, both nourished and transformed my initial insights into these women's writings, for I discovered that there was a broader context of exchange and dialogue than many have been willing to grant these women, and that their connections were reciprocal, rather than merely unidirectional along an axis of influence extending from the French metropolitan centre to the francophone periphery of Quebec.

5 Introduction

In addition, in the course of my readings of the last ten years, I have found it a particularly effective strategy to analyze feminist writing in French outside France if one wishes to look past an undifferentiated notion of French feminism and to gain a better understanding of both the specificity and the congruity of the feminist voices emerging during the period. In its transatlantic scope at least, the feminist activism of the 19703 thus distinguishes itself from other twentiethcentury intellectual and artistic movements that have had Paris as their epicentre, such as surrealism, the "new novel," or, more recently, the theoretical schools generated by post-structuralist thinkers like Derrida. It is nonetheless undeniable that much of the energy displayed in the feminist revival of the 19705 came from the same kind of contestation and dissidence that have characterized past avant-garde or revolutionary currents. What Kristeva so cogently points out in the Tel Quel article cited above, however, is the difficulty that women can experience in maintaining a dissident stance when they are so biologically and psychologically identified with maternity, and thus with perpetuating the social order which the reproduction of the species implies. As she puts it, "Si la grossesse est un seuil entre nature et culture, la maternite est un pont entre singularite et ethique. Une femme s'en trouve done, par les evenements de sa vie, aux charnieres de la socialite - garantie et menace pour sa perennite [If pregnancy is a threshold between nature and culture, maternity is a bridge between singularity and ethics. Through the events of her life, a woman thus finds herself at the pivot of sociality - she is at once the guarantee and a threat to its stability]."4 It is this pivotal role occupied by women that so many 19705 feminists took as a point of departure for their efforts to rethink themselves and their ethical commitment to their sex, both politically, in terms of women's control of their bodies and reproductive capacity, and aesthetically, in the writing that some women elaborated in response to the need to rethink and revise the symbolic dimensions and representations of their lives. Since necessity is the mother of invention, as the proverb goes, many women who began to write in the heat of feminist fervour were seeking to invent on all possible fronts: to find new words for their experiences, to create new literary forms to express their visions, and to explore new mythic and symbolic paradigms that would allow women to think beyond their traditional roles as man's "other" and mother, and thus to liberate their creative and intellectual potential. As part of the renewal of feminism in the 19703, it was thus very important to understand and deconstruct traditional notions of maternity and to displace these in favour

6 Mothers of Invention

of other, more open visions of women's relationships to themselves and the dreams and desires through which they relate to the world. It should not be surprising, then, that most fiction written by women touched by feminism reflects a preoccupation with the figure of the mother. As psychoanalytic theory so compellingly shows us, the bond between child and mother is a primary one, and it can exercise a determining influence on a person's subsequent relationships with others, in addition to his or her development as an individual. A significant number of critics have already analyzed the importance of the mother figure and the question of maternity for women writers, both in France and in Quebec.5 Still, much remains to be done, as Kristeva puts it, to comprehend the diversity of approaches to "maternity, female creation, and the link between them" in women's fiction. In this study, it is my intent to explore these intimately linked problematics in the works of four women whose fiction of the mid- to late 19705 began to display a womancentred and often explicitly feminist aesthetic sensibility. Helene Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brossard, and Jeanne Hyvrard all invented their fictions out of a sense of necessity; their work clearly shows that they felt compelled to try out new forms and daring language and images in their efforts to imagine and revise the maternal and the feminine. Furthermore, because of their provocative, innovative writing, these women quickly emerged as leading voices for their generation and communities of women, making them influential literary "foremothers" in their own right in the two decades since their experimental texts first challenged readers to rethink the feminine in language. Mothers of Invention is thus a study with a dual purpose. First, as a corrective to past scholarship, it focuses on fiction in an attempt to show the enduring power of the creative impulses born of these women's personal experiences and feminist trajectories. I concentrate solely on novels by these authors because it is a genre they all practise and because, in its length and conventions, the novel offers a particularly inviting showcase for their creativity and target for their irreverent wit. Second, this study attempts to show how these women's fictions go further than so many, including Kristeva herself,6 have been willing to grant: in each case, the writing strategies deployed are examined for their subversive intent and effects, so that, collectively, the avant-garde nature of these women's work becomes clear. This second objective, outlined in the chapter that follows, will in fact provide a cohesive subtext for the succeeding analyses, which furnish support for my claim that these women deserve to be granted the status of the last avatar of the avant-garde in the twentieth

7 Introduction

century. In essence, then, this study emphasizes textual praxis, rather than the theoretical debates surrounding the essentialism of a "feminine writing," debates that have often evolved without adequate consideration of the innovative fictions elaborated by these authors and their contemporaries. Moreover, whereas in the past, critics have examined these writers almost exclusively in isolation from one another, my readings offer a broader, comparative perspective on what was a transatlantic community of women working towards similar political, ethical, and aesthetic goals with virtually identical creative strategies. While all these women's works demand that we read differently, with our minds open to their disruptive approaches to traditional narrative fiction, in the readings I perform I try to expose both the more approachable aspects and the enigmas of their writing. After an introductory chapter outlining the historical context of the renewal of feminism in France and Quebec, the justification for including the authors chosen, and the theoretical background for this study, each author is treated individually through close readings of her texts. I begin with Helene Cixous because of her international renown as a theorist of the feminine, but also because she was the most important literary voice for French feminism in the mid-1970s. My second chapter examines La (1976), a novel that Cixous published the year following "Le Rire de la Meduse" and La Jeune nee, and thus a work informed by her theoretical and political thinking of the period which for many continues to define her reputation today. As this novel opens with a scene of rebirth and discovery, it offers a fitting entry into the key problems facing the feminist writer, who must seek a voice and create a space - give birth to herself, in other words - in a language so often used to silence and elide women's presence. The following chapter deals with Madeleine Gagnon's Lueur, a novel published in 1979 but based on and even reprising work dating back to her collaboration with Helene Cixous on La Venue a Vecriture, which began in 1975. At the time, as Quebec's leading Marxist feminist, Gagnon was in particularly close contact with what was happening in France, in part because she had completed her doctorate there in the 19603, in part because she was pursuing an academic career that involved teaching French texts, with an emphasis on theory. Her close links and collaborative efforts with feminists from Europe constitute one of the justifications for considering these women as a community, involved with elaborating a self-consciously avant-garde feminist poetics. Moreover, Gagnon's Lueur offers one of the most notable examples of what the often-theorized "writing the

8 Mothers of Invention

body" might look like in practice, through its portrayal of the corporeal links between a grandmother figure and the narrator, who transmits her foremother's heritage of unspoken words and will. I devote the next chapter to Nicole Brossard's L'Amer ou le chapitre effrite (1977), a crucial text for literary feminism in Quebec and one that challenges the limits of genre as it plays with language and traditional gender roles in the creation of its "fiction-theory." Brossard is arguably the most internationally recognized Quebec feminist author today, and her move from formalism to a feminist-oriented textual experimentation in the mid-1970s can be seen as emblematic of the kind of shift in thinking and writing that many women performed during that time. Her clear lesbian commitment, however, makes much of her early work seem more radical in hindsight, in particular because of the powerful language with which she refuses "the reproduction of mothering" studied by psychoanalytic critics such as Nancy Chodorow.7 As Brossard puts it, in the signature phrase that has come to symbolize the power of her novel, "J'ai tue le ventre et je 1'ecris [I have murdered the womb and I am writing it]."8 In its thematic and metaphoric content, as in its fragmented form and poetic play with language, L'Amer continues to be one of the most innovative and challenging manifestations of feministinspired textuality. Finally, I examine the first three novels of Jeanne Hyvrard - Les Prunes de Cythere (1975), Mere la mart (1976), and La Meurtritude (1977) - a triptych in which images of a woman's madness are rethought from the perspective of the patient, who is desperate to understand the language being used to marginalize her. In fact, in all of the works chosen for this study, the conscious-use (and misuse) of language is central to the ways in which the authors try to defy normative readings as they borrow from poetic and mythic traditions to fuel their disorienting narratives. What is most interesting about Hyvrard, however, is how her resolutely heterosexual vision of a woman's plight leads her to a critique of maternity similar to that performed by Brossard, for in Hyvrard's textual world the mother is literally and figuratively a smotherer, and so must be resisted in order to ensure the daughter's survival and sanity. Furthermore, Hyvrard's extensive and lyrical use of repetitions within and across her early novels offers yet another example of how women were challenging the boundaries and possibilities of the genre as part of their efforts to rethink questions of gender. As with most avant-garde movements, the collective dynamism of these women's pursuit of an experimental textuality expressive of a feminist aesthetic did eventually wane. In the concluding chapter,

9 Introduction

I resituate the work of Cixous, Gagnon, Brossard, and Hyvrard within the evolution of their respective literary communities, tracing both the extent of their influence and their individual trajectories since the height of their creative engagement with feminist ideology. That all four women continue to pursue their creative visions today is a testimony to the endurance and compelling originality of the literary voices they have cultivated - voices that have made them such inspiring "mothers of invention" in the eyes of their contemporaries and, I dare hope, in those of many readers to come.

i History, Ideology, Theory: Tracing the Contexts of Feminist Writing in the 19705 in France and Quebec

THE REVIVAL OF FEMINISM IN FRANCE AND QUEBEC AND THE WRITING IT E N G E N D E R E D

The decade of the 19605 was a period of intellectual and political upheaval in both France and Quebec. In France, social and labour unrest contributed to the events of May 1968, which fostered a renewed consciousness of political efficacy and responsibility within the French intellectual community. In Quebec, following what has been called the "Grande Noirceur" (the great darkness) of the Duplessis era,1 this was the period of the Quiet Revolution, a time of dramatic change that saw a radical secularization and a massive socio-economic restructuring of the province. In both cases, one of the outcomes of such change was a revival of active feminism, the likes of which had not been seen since campaigns for women's suffrage.2 This revival of feminism, while not entirely unaware of earlier collective initiatives by and for women, was nonetheless rooted in specific conditions in the contemporary context of each country, conditions that ultimately produced movements with strikingly similar objectives and results. In France, even after Simone de Beauvoir published her foundational study Le Deuxieme Sexe in 1949, feminism did not immediately take hold as a mobilizing force for change, although some historians have pointed out the importance of the establishment of women's associations with reformist tendencies during the post-war era.3 Still, it was not until various leftist groups inspired

ii Feminist Writing in France and Quebec

and even initiated the student protests against the educational system in 1968 that French women began to find an effective voice for their collective frustrations and desire for social justice.4 In Quebec, while "democratization"5 of the educational system after Duplessis symbolically offered women new opportunities, the historians of the Clio Collective have documented that women were still not encouraged to take advantage of such openings and thus generally continued to enter fields consonant with the traditional view of women's "natural" abilities.6 If one adds to such educational issues the impetus of the more politicized labour forces in which women were also participating in the two countries, as well as the influential example of how radical feminism grew out of civil-rights activism in the United States,7 it becomes clearer how such social upheaval came to inspire French and Quebec women to mobilize in favour of radical social change. Still, perhaps because of the complex confluence of so many factors, very few historians or critics have fully elucidated the social and historical reasons for the virtually simultaneous renewal of feminism in so many Western countries.8 When global comments are offered, however, observers often suggest or imply that it was the egalitarian or reformist ideals fuelling the strikes and demonstrations of the 19605 which most directly fostered the growing realization among women that such ideals did not extend to them, inasmuch as they did not respond specifically to women's need for legal, economic, and social self-determination and equality. Such a linking between reformist ideals, social upheaval, and the rise of a feminist consciousness is not historically without precedent; one only has to look to the involvement of women such as Olympe de Gouges in the French Revolution for an important instance of such a conjunction. In this regard, what distinguishes the contemporary renewal of feminism from its precursors must be in part the international scope of the realization of the oppression suffered by women and the ensuing struggle for change. This struggle, coming at a time so rich in examples of the political impact of other collective efforts worldwide, seems to have been the most likely catalyst for the coalescence of women's energies into various influential feminist organizations,9 of which the Mouvement de liberation des femmes (MLF) and the Front de liberation des femmes (FLF) are, respectively, the best known examples in France and Quebec. This resurgence of politically active but heterogeneous women's liberation movements was accompanied in many countries by a new interest in the expression of women's condition and identity in writing, that medium which, in the hands of male authors, had so often

12 Mothers of Invention

served to silence the woman's voice and preserve her status as other, as object. Simone de Beauvoir articulates this problem succinctly in her introduction to Le Deuxieme Sexe: "[la femme] se determine et se differencie par rapport a rhomme et non celui-ci par rapport a elle; elle est rtnessentiel en face de 1'essentiel. II est le Sujet, il est 1'Absolu: elle est 1'Autre [woman is determined and differentiated in relation to man, and not the latter in relation to her; she is the inessential opposite the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute: she is the Other]."10 Coming after de Beauvoir's groundbreaking theoretical analysis of women's condition in Western culture, it is no wonder that, as Isabelle de Courtivron puts it, "the newly-radicalized feminists who emerged from May '68 aimed not so much at raising consciousness and claiming equity as they did at asserting differences and transforming structures. Significantly, they concentrated on language rather than on sociological or biological facts, and, instead of demanding acceptance into the symbolic order, were intent on altering, displacing and transforming that very order/'11 Along with various ongoing campaigns to improve women's legal and economic status, then, the decade of the 19703 witnessed increased theoretical and literary production by women about women, aimed in part at improving their current condition by confronting their historical subordination in language and culture. In 1974 Editions des femmes became the first contemporary French publisher to dedicate itself exclusively to women's writings. In addition, French women founded journals such as Le Torchon brule, Sorcieres, des femmes en mouvements (which saw various incarnations), and Questions feministes (edited by de Beauvoir), in order to provide a forum for their creativity and concerns. In Quebec one could similarly point to journals such as Quebecoises deboutte! and Les Tetes de pioche12 and to the establishment of Les Editions du Remue-menage and La Pleine Lune dedicated to the same purpose. These genderspecific incursions into the publishing world in France and Quebec offered an invaluable forum for a new literature that involved not only an affirmation of the woman as subject but also a valorization of a female or feminine tradition repressed or rejected by a cultural canon overwhelmingly dominated by male authors and authorities. It is this context that nurtured the generation of feminist writers who emerged during the 19703 in France and Quebec, that is, writers who display "an awareness of women's oppression-repression that initiates both analyses of the dimension of this oppression-repression, and strategies for liberation." This definition of feminism, elaborated in the prefatory remarks to Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron's classic anthology, New French Feminisms,13 is broad enough to encompass the

13 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec

visions of those women who have in fact openly rejected being called "feminists." Such rejection of the term has been due in part to its radical connotations in particular socio-political contexts and in part to "internal" differences in political and theoretical approaches which have proven divisive for women's movements in many Western countries.14 As defined by Marks and de Courtivron, however, the term "feminism" allows us to see more clearly what united so many women, pointing to the fundamental realization that inspired them to seek a voice, either literary or political, more or less concurrently in so many countries. Within such a perspective, differences in women's writings can be explored without losing sight of the importance of the feminist groundswell. Even if some critics, eager to preserve the originality of individual voices and conscious of the lack of focused "leadership" in the collective phenomenon, still shy away from speaking of a literary movement, it seems equally inaccurate to deny the commonality of purpose displayed in the works of so many women writers. To speak of this phenomenon, it seems appropriate to begin by using the concept of a community, for if, as some claim, feminism did not produce an identifiable literary school per se, we can see that it significantly affected and inspired the writings of many women authors such that a new polyphony of feminist voices emerged in texts on both sides of the Atlantic, which continues, although admittedly more sotto voce, even to this day. Indeed, it seems all the more fitting to describe this feminist outpouring in terms of a community when one remembers earlier communities of women and their role in the history of women's writing in French, beginning with Christine de Pizan's Cite des dames?5 The contemporary feminist writing community, while not unified around a single movement or central figure, nonetheless displays common directions in writing which in fact far exceed the localized scope of earlier communities of literary women.16 Contemporary women writers of Quebec and France, animated by the desire for an appropriate expression of their woman-centred visions, explore similar textual avenues and focus on the same kinds of problems in language and life, despite distance and cultural differences. But what of the exchange of ideas and common concerns that is also necessary for such a community to exist? While a cursory glance at much of the critical work to date might lead one to conclude that the French and Quebec women writers who began to publish in the wake of the renewed activism of the 19605 were at the time completely isolated from one another, this view is not accurate. In reality, some of these writers did find ways to maintain more than a peripheral awareness of their transatlantic colleagues'

14 Mothers of Invention

literary and theoretical activities and displayed a tangible sense of community in their writing. As it became apparent in the early 19705 that women's struggles for equality were of global consequence, the organization of international conferences on women and women's writing became an increasingly common occurrence and contributed to the establishment of a transatlantic feminist network. One of the earliest of such conferences was the 1975 "Rencontre quebecoise internationale des ecrivains," devoted to "La Femme et 1'ecriture." In addition to many of Quebec's promising writers and literati, this event was attended by such French authors and feminist theorists as Christiane Rochefort, Annie Leclerc, Dominique Desanti, and Michele Perrein. For Claire Lejeune, the only Belgian writer present and one of the conference's closing speakers, it was a key "first meeting"17 that permitted her to initiate important relationships with her North American counterparts such as Madeleine Gagnon, one of Quebec's most prominent and militantly Marxist women poets. In fact, Lejeune subsequently sent many of her texts to Gagnon and maintained a correspondence with her, in addition to returning to guest lecture several times at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal, where Gagnon was a professor.18 In turn, Gagnon visited Belgium and lectured there as well as in Paris, where she was welcomed, among others, by Christiane Rochefort and Annie Leclerc; Gagnon and Leclerc had in fact become close friends at the 1975 conference and collaborated on several occasions in the years that followed. Following as it did the two influential series of lectures given by the French feminist author Helene Cixous in 1972 and 1974, the 1975 conference in Montreal represented a watershed in these women's consciousness of international solidarity, in addition to serving as an expression of the sustained interest by those in Quebec feminist and literary circles in what their French contemporaries were producing.19 Although Quebec writers were clearly more informed about the literary scene in France than the reverse, one can also find contemporaneous evidence of interest on the part of French women writers in what was being thought and written by women in Quebec. A notable manifestation of this awareness is the collaborative effort of La Venue a 1'ecriture (1977), for which Helene Cixous invited the participation of Annie Leclerc and Madeleine Gagnon. As Gagnon described it in an interview, "Cixous avait lu mes textes et les avait aimes. Quant a Annie, nous nous sommes rencontrees au colloque et sommes tornbees en amour comme deux petites filles. Je crois qu'il y a eu une rencontre d'amour de nos textes .... Trois ecritures, trois demarches faites separement mais s'imbriquant les unes dans les autres [Cixous

15 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec had read my texts and had liked them. As for Annie, we met at the conference and fell head over heels like two little girls. I think that there was a meeting of hearts in our texts ... Three types of writing, three approaches developed separately but interwoven]."20 While one could legitimately argue that French feminist thought had more influence on the work of Quebec women writers than the reverse, such remarks show that the degree of awareness in each community of the other's presence and production was not insignificant. Given the similar historical circumstances surrounding and inspiring the concurrent activities of women writers in the two communities, as well as transatlantic collaborations and correspondences such as those outlined above, it is somewhat surprising that no systematic study has been undertaken to date that compares the work of Quebec and French feminist writers of the 19703. Indeed, most feminist literary critics have generally chosen to consider these writers in isolation or in relation to their local peers, and have thereby elided an important dimension of their works - their sense of connection with other women in the world, a conscious solidarity of purpose that defies borders and distance. It is my intent, in the close readings that form the core of this study, to bridge this critical gap and provide convincing evidence of the similarities and reciprocal influences that highlight the common matrix of ideas and strategies which effectively fuse the two communities into one larger, if loosely knit, literary context. THE Q U E S T I O N OF A NEW W R I T I N G BY/FOR WOMEN

Even if one is reluctant to grant that writings by feminists constitute a coherent literary movement in the 19703, it is clear that the community I have described does indeed have its pivotal texts, key moments of articulation that serve to inspire, and even enflame, the larger group of women participants. Two such texts, both from the pen of Helene Cixous, appeared in 1975, declared the "Year of the Woman" by the United Nations: "Le Rire de la Meduse" ("The Laugh of the Medusa") and La Jeune nee (The Newly Born Woman}.21 In these essays, Cixous articulates both the aspirations and the anger common to so many of her contemporaries, for she calls women to writing in order to undo their alienation in Western society and literature, challenging them to speak and write their difference and to have confidence in the power of their creativity to express their desires. This new writing is something she calls "ecriture feminine," a term that has remained unshakably identified with Cixous's thought and writing ever since: "Je parlerai de 1'ecriture feminine: de ce qu'elle fera. II

16 Mothers of Invention

faut que la femme s'ecrive: que la femme ecrive de la femme et fasse venir les femmes a 1'ecriture, dont elles ont ete eloignees aussi violemment qu'elles Tont ete de leurs corps; pour les memes raisons, par la rneme loi, dans le meme but mortel. II faut que la femme se mette au texte - comme au monde, et a 1'histoire, - de son propre mouvement [I shall speak about women's writing: about what it will do. Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies - for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Woman must put herself into the text - as into the world and into history - by her own movement]" (Rire 39).22 This dramatic opening to "Le Rire de la Meduse" provided both a beacon and a catch phrase for women writers and their critics, focusing the debate on the "difference" of the new writing that many claimed women were or could be producing. The first urge, of course, was to try to explain the term, to typify the writing it described, a writing that many thought Cixous's daring essay exemplified, even as it denied the very possibility of absolute definition: Impossible de definir une pratique feminine de 1'ecriture, d'une impossibilite qui se maintiendra car on ne pourra jamais theoriser cette pratique, 1'enfermer, la coder, ce qui ne signifie pas qu'elle n'existe pas. Mais elle excedera toujours le discours que regit le systeme phallocentrique ... Elle ne se laissera penser que par les sujets casseurs des automatismes, les coureurs de bords qu'aucune autorite ne subjugue jamais. (Rire 45) [It is impossible to define a feminine practice of writing, and this is an impossibility that will remain, for this practice can never be theorized, enclosed, coded - which doesn't mean that it doesn't exist. But it will always surpass the discourse that regulates the phallocentric system ... It will be conceived of only by subjects who are breakers of automatisms, by peripheral figures that no authority can ever subjugate.] (Laugh 883)

Though Cixous here attempts to escape the dangers of having her thinking immobilized by labels and definitions, the body of her essay is nonetheless suggestive of her perspective; her insistence that women write is accompanied by her reflections on the nature of the new writing they might produce, which, although she is careful not to link it entirely to the sex of the author, still seems to involve a privileging of the female body "with its thousand and one thresholds of ardor" (Laugh 885). As she says, "il faut que la femme ecrive par son corps, qu'elle invente la langue imprenable qui creve les cloisonnements, classes et rhetoriques, ordonnances et codes [women must

17 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes, and rhetorics, regulations and codes]" (Rire 48, Laugh 886). Although for Cixous, "il n'y a pas ... une femme generate, une femme type [there is ... no general woman, no one typical woman]," to which she adds that "on ne peut parler d'une sexualite feminine [you can't talk about a female sexuality]" (Rire 39, Laugh 876), her essay does address a collectivity of women and their common experience, with remarks such as "[s]'il y a un 'propre['] de la femme, c'est paradoxalement sa capacite de se de-proprier sans calcul ... Sa libido est cosmique, comme son inconscient est mondial [if there is a 'property' that is uniquely woman's, it is her ability to divest herself of everything unselfishly ... Her libido is cosmic, just as her unconscious is worldwide]" (Rire 50). By exploring the question of difference and by positing an alternative, "feminine" libidinal economy complementary to the "masculine" one privileged by Freud, Cixous tries to find an opening and a voice for what emerges from women's unconscious, a source of inspiration for writing that cannot but upset the traditional, phallocentric order because of its difference: Un texte feminin ne peut pas ne pas etre plus que subversif: s'il s'ecrit, c'est en soulevant, volcanique, la vieille croute immobiliere, porteuse des investissements masculins, et pas autrement; il n'y a pas de place pour elle si elle n'est pas un il? Si elle est elle-elle, ce n'est qu'a tout casser, a mettre en pieces les batis des institutions, a faire sauter la loi en 1'air ... Parce qu'elle ne peut pas, des qu'elle se fraye sa voie dans le symbolique ne pas en faire le chaosmos du "personnel," de ses pronoms, de ses noms et de sa clique de referents. (Rire 49) [A feminine text cannot fail to be more than subversive. It is volcanic; as it is written it brings about an upheaval of the old property crust, carrier of masculine investments; there's no other way. There's no room for her if she's not a he. If she's a her-she, it's in order to smash everything, to shatter the framework of institutions, to blow up the law ... For once she blazes her trail in the symbolic, she cannot fail to make of it the chaosmos of the "personal" - in her pronouns, her nouns, and her clique of referents.] (Laugh 888) It is on the basis of this "chaosmos"23 on the level of language (the symbolic) that Cixous predicts the development of a writing in the feminine, a writing drawing on the feminine unconscious and its drives which could revolutionize our vision of sexuality, textuality, and thus reality, for "1'ecriture est la possibilite meme du changement [writing is precisely the very possibility of change]" (Rire 42, Laugh 879). The effect of this essay and the concomitant publication of Cixous's lengthier and more precise formulations on femininity in La ]eune nee

i8 Mothers of Invention would be hard to overestimate, particularly if considered on an international scale. In fact, while the term "ecriture feminine" appears prominently only in the beginning of "Le Rire de la Meduse" and far more discreetly in La Jeune nee,24 it nevertheless quickly provided the impetus for a multitude of contemporary feminist writings and became the focal point of a lively debate on questions of essentialism and the nature of feminine difference. Some, such as Irma Garcia in her Promenades femmilieres: Recherches sur I'ecriture feminine,25 accepted the concept of feminine writing without question and set out to inventory its manifestations, while others, less convinced, probed the questions it raised from various angles. Claude Pujade-Renaud, for instance, although interested in the relationship between the female body and writing, nonetheless astutely cautioned against the tendency to "enfermer les productions des femmes dans un regionalisme dialectal ou dans un regionalisme sexue, limite aux zones erogenes [confine Women's output to a dialectical regionalism or a sexual regionalism, limited to the erogenous zones]."26 Indeed, however Cixous has tried to reformulate her ideas since 1975 - and she has repeatedly articulated her dissatisfaction with terms such as "masculine" and "feminine," which she uses for expediency27 - it seems that "ecriture feminine" will always be read as central to her writing and theory. While Cixous's reflections on the feminine and writing, along with those of her contemporaries Annie Leclerc, Luce Irigaray, and Julia Kristeva,28 fuelled imaginations and offered direction for women writing in France and elsewhere, similar ideas were also appearing in the writings of Quebec feminists. As Karen Gould explains in her invaluable study Writing in the Feminine: Feminism and Experimental Writing in Quebec, the development of feminism in Quebec was significantly influenced by nationalism and socialism and the discourse of decolonization that such ideological commitments engendered (WF 10-17). In addition, many Quebec feminists were inspired and influenced as much by anglophone feminists as by the French; the film Some American Feminists, made by Luce Guilbeault and Nicole Brossard in the mid-1970s, is a who's who of American feminists which shows the Quebec women's acute awareness of their American peers' activities and thought.29 Still, in terms of theoretical reflections, one would be hard put to single out a Quebec text contemporary with "Le Rire de la Meduse" that served in the same way to focus discussion. Even the 1971 Manifeste des femmes quebecoises did not attain the status of a founding text, despite its consciousness-raising ambitions.30 In Quebec at least, "theory" from at home and abroad seems more often to have been incorporated into creative endeavours, or

19 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec when it was articulated, seems not to have become an immediate nexus for debate within the feminist community. This phenomenon would perhaps explain the subversive effect (and the relative success) of novels such as Louky Bersianik's L'Euguelionne (1976) and Nicole Brossard's L'Amer ou le chapitre effrite (1977), which offered analyses of women's oppression and repression from within the frame of fiction. Indeed, although both authors would eventually publish collections of theoretical reflections, these would not appear until after the feminist movement's crest: Brossard's La Lettre aerienne dates from 1985, while Bersianik's La Main tranchante du symbole came out as late as 199O.31 These observations are not to imply that Quebec women did not theorize their condition and ideals at the time of feminism's heyday, for one has only to look at some of the texts published since Madeleine Gagnon's "Mon Corps dans 1'ecriture," the essay she began writing as early as 1975 for La Venue a 1'ecriture (1977), to be persuaded otherwise.32 Nicole Brossard's La Lettre aerienne (1985) in fact includes texts dating from 1975 and 1978, in addition to more recent material. One could also cite, for example, Madeleine OuelletteMichalska's L'Echappee des discours de I'ceil (1981), France Theoret's Entre raison et deraison (1987), or the collaborative effort of La Theorie, un dimanche (i988).33 Such theoretical texts, products more than initiators of exchanges within Quebec's feminist community, both borrow from and build upon works by their French and American counterparts, tackling many of the same ideas and suggesting various liberatory strategies for women's writing. Theoret, in Entre raison et deraison, succinctly articulates the distinctions made in Quebec between feminist and feminine writing and "writing in the feminine" (here termed "ecriture au feminin"): Ce que nous avons designe sous 1'expression ecrits feministes ce sont les essais, les textes manifestaires, les temoignages, c'est-a-dire les ecrits qui participent de la communication. Nous avons appele litterature feminine les ceuvres litteraires qui ne remettent pas en question, dans le langage, les stereotypes feminins. L'ecriture au feminin proprement dite propose 1'emergence du sujet feminin dans un langage conscient du fait que la langue patriarcale rend souvent invisible le feminin. L'emergence du feminin confronte le symbolique, repensant tout autant 1'unite lexicale et le genre litteraire.34 [What we have designated by the term feminist writings are essays, manifestos, and testimonies, that is, works that perform a communicative function.

2O Mothers of Invention We have called feminine literature the literary works that do not throw into question, in and via language, feminine stereotypes. Actual writing in the feminine proposes the emergence of the feminine subject in a language conscious of the fact that patriarchal speech often renders the feminine invisible. The emergence of the feminine confronts the symbolic, rethinking both lexical units and literary genre.]

While such practical distinctions, which show among other things the qualified use of the terms "feminist" and "feminine" in Quebec, could still be considered refinements of Cixous's original conceptions, they should also be seen in their complementarity to the more sexually and politically radical theories of Nicole Brossard or Madeleine Gagnon. Unlike Cixous in her theory, these two writers insist on both the metaphorical and the more literal importance of the body in the production of a female textuality and authority. As Gagnon writes in "Mon Corps dans recriture," Je veux etre douce, douce et tout dire. Couler comme du bon lait que je buvais ou que je donne. La liberation des femmes, e.a veut dire la parole du corps ... Je veux deshabiller ce corps et 1'habiter. Je veux le meubler de mots, couvrir les places qui m'attendent, les blancs laisses la par son histoire d'ecritures qui jusque-la m'avaient echappe ... Et s'il faut parfois que la syntaxe s'erupte et s'insurge centre la linearite apprise, je suivrai les mouvements, les emiettements paradigmes du mien, jusqu'au lexique qui ne m'est pas etranger mais refuse par des flics du bon ordre.35 [I want to be gentle, gentle and explicit. To flow like good milk that I used to drink or that I give. Women's liberation means the language of the body ... I want to undress that body and inhabit it. I want to furnish it with words, cover the places that await me, the blank spaces left there by its history of writings that had until then escaped me ... And if sometimes this means syntax must erupt and revolt against acquired linearity, I will follow the movements, the shattered paradigms that are mine, even into a vocabulary that is not alien to me but denounced by the cops of law and order.]36

If, as Karen Gould asserts, the most prominent Quebec feminist writers differ from Cixous in that they "consistently understood their own approach to writing in the feminine as a gender-marked experimental writing practice in which women alone are engaged, rather than as an anti-logocentric or anti-phallocentric approach to writing that male and female writers alike might pursue" (WF 38), we can nonetheless see in texts such as Gagnon's a drive, similar to Cixous's, to write her desires and her body in terms expressive of their difference. In effect, what all these women are searching for is a writing

21 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec

which, whether or not it is articulated through the trope of the female body, will introduce more than just a new, woman-centred thematic network into the novel. As shown in the last sentences of the passages by Theoret and Gagnon quoted above, both insist upon language as the privileged site of change, a change that involves a conscious displacement of women from their place of silence in the symbolic, along with a deliberate textual inscription - a (re)placement - of a gender-marked voice and subjectivity, which Louky Bersianik has called women's "gynility."37 What tends to be elided in some of the theoretical and critical discussions of femininity in the texts of French and Quebec women writers is the problem of equating a theory of "ecriture feminine" with the real project of writing. Devotees of the theory vehemently reject accusations of essentialism, but in doing so, they neglect some of the other questions that arise when textuality is so linked with female sexuality and the unconscious. Claude Pujade-Renaud, for example, points out that 1'avenement d'un "ecrire-femme" repose, entre autres, sur ce glissement du corps a 1'inconscient ... par rapport a ce mythe d'une continuite reliant inconscient-corps-ecriture, il convient de rappeler combien le corps peut aussi servir de defense centre 1'inconscient ou combien 1'inconscient peut venir s'y camoufler en un jeu de derobades symptomatiques. Ainsi des "maux-de-corps" de 1'hysterique. L'illusion serait de croire que ces "mauxde-corps" pourraient, d'eux-memes, se transformer en "mots-de-corps."38 [the advent of a "woman-writing" depends, among other things, on this slippage from the body to the unconscious ... with respect to this mythic continuity linking unconscious-body-writing, it is worth recalling to what extent the body can also serve as a defence against the unconscious or how the unconscious can be camouflaged by the body in a play of symptomatic evasions. Thus the "body-woes" of the hysteric. The illusion would be to believe that these "bodywoes" could, on their own, transform themselves into "body words."]

If there is no unmediated relation to the body, then it seems that what is more important is to scrutinize the mediation, that is, language and the way it is used to construct, deconstruct, or reconstruct the notion of femininity. Writing in the feminine in this sense is perhaps better described as feminist writing, for it is the ideological angle with which these women come to writing that motivates their deliberate (mis)use of language as they rewrite and invent representations of the feminine adequate to their woman-centred visions. In essence, my premise is that "ecriture feminine," while powerful as an ideal, has less of a real existence than many critics and feminists

22 Mothers of Invention

alike have been willing to admit. At best, one can say that in searching for new means to express the reality of women's subjectivities, desires, and visions, these women writers bring new perspectives to the literary forms and the content they choose: their transgressive explorations of textuality are illuminating but cannot by themselves succeed in overthrowing the structures of language or society in any definitive way. As early as 1978, Madeleine Gagnon herself seems to realize this problem, when she speaks of her vision of the collective feminist project in terms of the metaphor of an illuminated book: Nous devons operer un re-centrement, hors de la tradition elitiste et exclusiviste. Non pas un logo-centre. Mais un centre enluminure ou le texte et les marges se joindront. Nous devons joyeusement nous astreindre a un double travail historique: travail de de-construction de leurs projections de nous, non pas liberantes mais alienantes; travail de resurrection de nos mortes mal lues, de nos mortes non muettes.39 [We must conduct a re-centring, outside the elitist and exclusionary tradition. Not a logo-centre. But rather an illuminated centre where the text and the margins will conjoin. We must joyously apply ourselves to a double historical task: a de-construction of their projections of us, which are not liberating but alienating, and a resurrection of our poorly read ancestors, of our non-mute foremothers.]

Gagnon here does not pretend to do away with the book of history, but rather, she advocates looking at it in another way, shifting the centre of our attention from the symbolic hegemony of men's words towards the (re)discovery of images and texts more reflective of women's stories. In her vision, "text and margin will be conjoined" and are thus to be considered concomitantly, rather than one at the expense of the other. Clearly, this is a pragmatic - some might even say conciliatory - view of what can reasonably be accomplished by women's incursions into the logocentric annals of tradition. Perhaps a similar kind of pragmatism explains why, in New French Feminisms, Marks and de Courtivron placed Cixous's "Rire de la Meduse" in the section entitled "Utopias," rather than with the texts they classify as "Creations" or "Manifestoes - Actions."40 Pragmatism is certainly one of the reasons that Nicole Brossard, for her part, insists on her "strategic" use of the term "ecriture feminine," for as she says, "le rapport qu'un sujet a a 1'ecriture a mon avis est identique pour un homme et pour une femme. Ce qui est important, c'est la notion de sujet. C'est un rapport qu'un sujet pose [the relationship that a subject has to writing is, in my opinion, identical for a man and a

23 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec

woman. What is important is the notion of the subject. It is a relationship that a subject posits]."41 And in feminist fiction at least, this relationship is posited consciously, always already coloured by an ideological position, for if, to repeat a famous slogan, "la vie privee est politique" (the personal is political), then the writing of women's desires must ineluctably be so too. HELENE CIXOUS, MADELEINE GAGNON, NICOLE BROSSARD, AND JEANNE HYVRARD:

FOUR "MOTHERS OF I N V E N T I O N "

Just as feminism brought into sharper focus the personal dimensions of the political, so feminist literary criticism has shown reinvigorated interest in the intimate and in the author's context because they may significantly enrich the reading of a text. This move away from the "author is dead" school of criticism is particularly pertinent for works by women whose lived experiences shape and fuel their writing and for whom, to borrow Brossard's phrase, "[ejcrire je suis une femme est plein de consequences" (to write I am a woman is full of consequences) (L'Amer 53). For this study, where my principal focus is on close readings, I too feel that it is essential to recall who the writers I have chosen are, and why they are important in the history of feminist literature and beyond. I have chosen to limit the scope of my analysis to those subjects who are exemplary, at least in some sense, and yet allow for the most pertinent and interesting discussion of individual literary originality. Furthermore, the time frame within which the chosen texts fall is relatively short, ranging from Cixous's publication of "Le Rire de la Meduse" in 1975 to the appearance of Gagnon's novel Lueur in 1979, a period which is roughly that of the height of feminist literary experimentation. Naturally, this focus has meant that certain important and interesting authors whose work falls outside this period have been omitted, including Monique Wittig, a key figure in the earliest stages of French feminist renewal, whose experimental novels Les Guerilleres (1969) and Le Corps lesbien (1974) were influential for many in the movement in which she was a pioneer.42 Writers such as Chantal Chawaf, who published her first book at Editions des femmes in 1974, or Louky Bersianik and France Theoret, whose first major works appeared during the same period in Quebec, are also excluded because their work is similar to that of the authors I have chosen, because it is not sufficiently experimental, or because their most interesting publications were not part of the initial creative groundswell.

24 Mothers of Invention

It thus is for reasons of timing, eminence, and originality that the chapters of this study are dedicated to four writers who emerged from the social unrest of the 19605 and early 19705 with a new feminist voice in writing, namely, Helene Cixous, Madeleine Gagnon, Nicole Brossard, and Jeanne Hyvrard. Of these four, Cixous is undoubtedly the most prominent. A Joyce scholar and key participant in the founding of the Vincennes campus as an alternative to the repressive environment of the existing Parisian universities, she began her writing career in 1967 with the short stories of Le Prenom de Dieu, which was followed by Dedans in 1969, a first novel for which she received the prestigious Prix Medicis. Since these first publications, Cixous has written at what sometimes seems an astonishing rate: at the threshold of the new millennium, she already had to her credit over twenty-five novels, several highly acclaimed plays, and some shorter works of fiction, as well as a number of influential theoretical texts among the many articles and essays for which she is perhaps still best known in North America. While all of Cixous's work is concerned with revitalizing language and the patterns of traditional narrative, it is possible to see her career in terms of cycles or periods. The early works, informed (some might say overly so) by the discourses of deconstruction and psychoanalysis that are part of her intellectual landscape, are marked by a radical subversion of character, plot, and language not uncommon in the work of French writers influenced by Joyce and by the generation of experimental writing associated with the "nouveau roman." Cixous's first works were followed by a shift in the mid-1970s toward less neutral, more woman-centred, if not openly feminist, narratives and a commitment to publish with Editions des femmes.43 This period, during which she founded the Centre de recherches en etudes feminines at the Universite de Paris vin in 1974, was the most important in terms of her theoretical writing on difference and femininity. More recently, Cixous has produced a considerable body of writings for the theatre and in her fiction has moved toward an increasingly limpid and often more autobiographical prose whose clarity could perhaps be linked in part to her appreciation for the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, which began when she encountered the latter's texts in the late 1970s.44 As it is a new feminist consciousness in literature that interests us here, the "middle" period of Cixous's writing will be our focus, as seen through the lens of a detailed analysis of La. This novel, first published in 1976 by Gallimard and reprinted in 1979 by Editions des femmes, is perhaps most closely associated chronologically and in content with the theoretical works "Le Rire de la Meduse" and La

25 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec

Jeune Nee. While it was not the first of her novels to deal with questions of sexual difference, it is arguably both the most obviously feminist and the most accessible of the period, since it is far less hermetic than texts such as Partie, for example, another work she published that year. While I will not hesitate to mention other novels where pertinent, La seems an appropriate text to open my discussion, especially since it has not received as much sustained critical attention as Cixous's other contemporaneous works, such as Souffles or the successful theatrical production of Le Portrait de Dora. Very close to Cixous in age, Madeleine Gagnon also shares with her Algerian-born contemporary the prestige of a French graduate education and the experience of an academic career. Gagnon left her birthplace of Amqui on the Gaspe Peninsula to pursue undergraduate studies in literature in Acadia and then a master's degree in philosophy at the Universite de Montreal. She then spent most of the crucial decade of the 19605 in France, where she successfully defended her thesis on Claudel in 1968, the same year that Cixous obtained a doctorate for her influential reading of Joyce's Finnegan's Wake. Given this coincidence, it is surely not surprising that the writings of these two women display strikingly similar frames of reference and areas of theoretical concern. By pursuing an education in France when they did, they both witnessed and were part of a decade of extraordinary intellectual effervescence, when existentialism and its emphasis on "engaged" writing was waning in the face of challenging new discourses on politics, language, and textuality that were discussed and disseminated in, among other places, the pages of the journal Tel Quel (1960-82), that "vast and powerful intellectual enterprise that terrorized the French intellectual scene for over two decades," as one literary historian puts it.45 Notwithstanding their individual trajectories, it is apparent that both Gagnon and Cixous were marked by the intellectual air du temps; they both found creative inspiration in the insights of Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, and their early works are all informed to some degree by an understanding of the discourses of Marxism and structuralism, as well as of the theories of contemporary philosophers and critics such as Derrida, Foucault, and Kristeva. In a final coincidence of note, the two women also began their writing careers at approximately the same time, choosing the short-story form for their first publications: Gagnon's Les Morts-vivants appeared in 1969, a mere two years after Cixous's Prenom de Dieu. Since returning to Quebec to take up a position in literature at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal (which she held from 1969 to 1982), Gagnon has enjoyed a sustained career, with some fifteen works of

26 Mothers of Invention

prose and eleven collections of poetry to her credit, as well as two retrospective anthologies entitled Autographic i and 2 (1982 and 1989 respectively). During the 19705 she became a prominent, figure on Montreal's literary and ideological scene, co-founding the radical leftist journal Chroniques in 1975 and participating in union leadership at the university, even as she was writing the militant Marxist poetry of Pour lesfemmes et tons les autres (1974) and Poelitique (1975), the former of which is considered by some to be the first clearly feminist collection of poetry in Quebec.46 Interestingly enough, Gagnon's awakening to feminist thinking and her shift in interest towards women's issues are contemporaneous with, if not earlier than, Cixous's own, although the latter's publications and academic initiatives perhaps seemed to respond more quickly to the new groundswell at the time. As the previously unpublished text entitled "Inedit" included in Autographic i shows, as early as 1971 Gagnon was inspired by her reading of the influential double issue of Partisans dedicated to the "Liberation des femmes, annee zero" in 1970. In addition to mentioning this "beau titre, [qui] fait du bien [beautiful title, (that) heartens one]" (Ai, 41), she also gives a list of intellectual references and reflections on her own writing, concluding: "Je veux ecrire un autre livre. J'oscille entre poesie et roman. Cette hesitation va me poursuivre longtemps. J'ai 1'impression. Je fais des encres [I want to write another book. I hesitate between poetry and the novel. This hesitation will dog me for a long time. I have the impression. I am doing some ink drawings]" (Ai, 42). As it turned out, Gagnon opted to voice her resolutely Marxist and increasingly feminist ideological convictions primarily in poetry in the early 19705, although she did contribute the prose text of "Amour parallele" to Portraits du voyage (1975), signing it with the nickname "la gentille lionne" (the kind lioness), inspired, it would seem, by Cixous's use of the expression in Portrait du soleil (i974).47 That Gagnon knew this novel well is confirmed by the interview with Cixous that she did for the February 1975 issue of Chroniques, entitled "Entretien: Dora et Portrait du soleil. Madeleine Gagnon, Philippe Haeck et Patrick Straram le Bison ravi parlent avec Helene Cixous." Notably, this issue of the journal was devoted to the theme "Liberation de la femme et lutte des classes" (Women's liberation and class struggle), a title that reflects the increasing priority of feminism over Marxism that would take hold in Gagnon's work from this point on. The period of Gagnon's most evident feminist engagement, 197579, is also one during which her emphasis shifted mainly to prose, in the form of articles for journals (especially Chroniques}, theoretical essays such as "Mon Corps dans 1'ecriture" for La Venue a I'ecriture,

27 Feminist Writing in France and Quebec