Lassalle: The Power of Illusion and the Illusion of Power 1494087669, 9781494087661

This is a new release of the original 1932 edition.

701 86 7MB

English Pages 334 [335] Year 1931

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

Illustrations

Translators’ Prelude (Testimonies of Authors)

Part One

Chapter One. Thirty Thousand New Citizens

Chapter Two. Strong Measures

Chapter Three. Applied Trinity

Chapter Four. Commercial Academy

Chapter Five. Herr Schulz on Punctuation

Chapter Six. God’s Soliloquy

Chapter Seven. The Dandy of the Revolution

Chapter Eight. Gladiators

Chapter Nine. The Three Musketeers

Chapter Ten. The Rebellion of the Kings

Chapter Eleven. The Graveyard of Illusions

Chapter Twelve. Intermezzi

Part Two

Chapter One. Berlin!

Chapter Two. Miscarriage of the Tragedy

Chapter Three. Blank Cartridge and Ball Cartridge

Chapter Four. Time For the Heart

Chapter Five. Soap-Bubbles

Chapter Six. What Next?

Chapter Seven. The Theses Are Posted Up

Chapter Eight. Conspirators

Chapter Nine. Last Battles

Chapter Ten. An Idyll and Its Upshot

Chapter Eleven. The Murder of a Dead Man

Chapter Twelve. Ritournelle

Index

Citation preview

LASSALLE

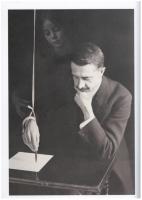

Lassalle as a young man From a pastel in the possession of the German Social Democratic Party

LASSALLE THE

POWER OF I L L U S IO N AND T H E IL L U S IO N OF POW ER by

ARNO SGHIROKAUER TRANSLATED BY

EDEN & CEDAR PAUL ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK T H E CENTURY COMPANY 1932

The German original of this work, entitled “Z assalle, die Macht der Illusion, die Illusion der Macht", was published in 192& FIRST

P U BL I S H E D

IM THB

U.S.A.

IM I 9 3 2

A ll rights reserved PRINTED UNW IN

IN

GREAT

BROTHERS

BRITAIN

LTD .,

BY

WOKING

CONTENTS FACS t r a n sl a t o r s' p r e l u d e

( t e s t im o n ie s

PART

of

a u t h o r s)

II

ONE

CHAPTER ONE

THIRTY THOUSAND NEW CITIZENS

23

CHAPTER TWO

STRONG MEASURES

32

CHAPTER THREE

APPLIED TRINITY

43

CHAPTER FOUR

COMMERCIAL ACADEMY

50

CHAPTER FIVE

HERR SCHULZ ON PUNCTUATION

64

CHAPTER SIX

GOD’S SOLILOQUY

73

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE DANDY OF THE REVOLUTION

82

CHAPTER EIGHT

GLADIATORS

93

CHAPTER NINE

THE THREE MUSKETEERS

I0 8

CHAPTER TEN

THE REBELLION OF THE KINGS

12 5

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE GRAVEYARD OF ILLUSIONS

13 5 15 1

CHAPTER TW ELVE INTERMEZZI

PART

TWO

CHAPTER ONE

BER LIN !

165

CHAPTER TWO

MISCARRIAGE OF THE TRAGEDY

183

CHAPTER THREE

BLANK CARTRIDGE AND BALL CARTRIDGE

19 6

CHAPTER FOUR

TIME FOR THE HEART

208

CHAPTER FIVE

SOAP-BUBBLES

226

CHAPTER SIX

W HAT NEX T?

242

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE THESES ARE POSTED U P

25O

CHAPTER EIGHT

CONSPIRATORS

259

CHAPTER NINE

LAST BATTLES

276

CHAPTER TEN

A N IDYLL AND ITS UPSHOT

286

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE MURDER OF A DEAD MAN

299

CHAPTER TW ELVE

RITOURNELLE

308

INDEX

312

ILLUSTRATIONS Frontispiece

l a s s a l l e a s a YOUNG m a n

From a pastel in the possession of the German Social Demo cratic Party FACING PACK

HOUSE IN BRESLAU W HERE LASSALLE WAS BORN

48

LAS8ALLE AS PUPIL AT THE

49

LEIPZIG COMMERCIAL ACADEMY

After a picture in the possession of Professor Gustav Mayer LASSALLE A T TWENTY-SEX

80

During the Hatzfeldt trial LASSALLE

8l

After an oil-painting in the possession of the Vienna "Arbeiter zeitung” COUNTESS SOPHIE HATZFELDT IN 1 8 4 0

128

From a painting 12 8

COUNTESS SOPHIE HATZFELDT

From a woodcut LASSALLE

I2g

HEGEL

I76

After a painting by Sebbers CARICATURE ILLUSTRATING THE HATZFELDT AFFAIR, s h o w in g

Lassalle, Countess H atzfeldt, an d her son C ount Paul

177

KARL MARX

192

GIUSEPPE GARIBALDI

19 3

From the ‘‘Bibliothek wertvoller Memoiren” A LITTLE-KNOWN PORTRAIT OF LASSALLE

256

In the possession of the Herwegh family HELENE VON DÖNNIOES IN 18 6 4

257

HELENE VON DÖNNIOES IN 1 8 7 2

257

HELENE VON DÖNNIOES

304

After a painting by Franz von Lenbach DEATH-MASK OF LASSALLE HEAD FROM THE LASSALLE MONUMENTIN VIENNA

305

Tailpiece

The illustrations facing pages 5, 49, 80-1, 128, 256-7, 304-5 are reproduced, by Per mission of Messrs. R. L. Prager, Berlin, from their publication “Ferdinand Lassalle”

TRANSLATORS’ PRELUDE (TESTIMONIES OF AUTHORS)

K arl M arx, in a letter to Schweitzer, under date October 13, i 860 As regards the Lassallist Union, it was founded during a period of reaction. When the labour movement had been slumbering in Germany for fifteen years, Lassalle wakened it once more, and this was his imperishable service. But he made great mistakes. He was unduly influenced by the cir cumstances of the time. . . . With the demand for State-help on behalf of associations, he combined the Chartist demand for universal suffrage. He overlooked the difference between German and English conditions. Also from the very start, like every one who believes that he has in his pocket a panacea for the sufferings of the masses, he gave a religious sectarian character to his agitation. . . . Being the founder of a sect, he repudiated all natural connexion with the earlier movements. He . . . did not seek his concrete foundations in the actual elements of the class movement, but wished to prescribe its course to the class movement in accordance with a doctrinaire prescription of his own.

G eorge M eredith , in The Tragic Comedians (1880) i (In Chapter II, before “ Clotilde” meets “Alvan” ) “Who is the man they call Alvan?” She put the question to an aunt of hers. Up went five-fingered hands. This violent natural sign of horror was comforting ; she saw that he was a celebrity indeed. “Alvan ! My dear Clotilde ! What on earth can you want to know about a creature who is the worst of demagogues, a disreputable person, and a Jew ?”

12

LASSALLE

Glotilde remarked that she had asked only who he was. “ Is he clever?” “ He is one of the basest of those wretches who are for upsetting the Throne and Society to gratify their own wicked passions : th at is what he is.” “But is he clever?” “Able as Satan himself, they say. He is a really dangerous bad man. You could not have been curious about a worse one.” “ Politically, you mean?” “ O f course I do.” The lady had not thought of any other danger from a man of that station. The likening of one to Satan does not always exclude meditation upon him. . . . n (In Chapter III, when “Clotilde” meets “Alvan” ) “The three stepped into the long saloon, and she saw how veritably magnificent was the first she had noticed. . . . This m an’s face was the bom orator’s, with the light-giving eyes, the forward nose, the animated mouth, all stamped for speechfulness and enterprise, of Cicero’s rival in the forum before he took the leadership of armies and marched to empire. The gifts of speech, enterprise, decision, were marked on his features and his bearing, but with a fine air of lordly mildness. . . . One could vision an eagle swooping to his helm by divine election. So vigorously rich was his blood that the swift emotion running with the theme as he talked pictured itself in passing, and was like the play of sheet-lightning on the variations of the uninterrupted and many-glancing outpour. Looking on him was listening. Yes, the looking on him sufficed. Here was an image of the beauty of a new order of godlike men. . . . Could that be the face of a Jew? She feasted. It was a noble profile, an ivory skin, most lustrous eyes. Perchance a Jew of the Spanish branch of the exodus, not the Polish. There is the noble Jew as well

TRANSLATORS’ PRELUDE

13

as the bestial Gentile. There is not in the sublimest of Gen tiles a majesty comparable to that of the Jew elect. He may well think his race favoured of heaven, though heaven chastise them still. The noble Jew is grave in age, but in his youth he is the arrow to the bow of his fiery Eastern blood, and in his manhood he is, ay, what you see there ! a figure of easy and superb preponderance, whose fire has mounted to inspirit and be tempered by the intellect.

P rince Bismarck, speaking in the Reichstag on April 2, 1881 Lassalle . . . wanted urgently to enter into negotiations with me. . . . Nor did I make it difficult for him to meet me. I saw him, and since the first few hours* conversation with him, I have never regretted my action. . . . O ur relations could not possibly take the form of political negotiations. What could Lassalle offer or give me? He had nothing to back him up, and in all political negotiations “do ut des*' is implied, even though it be felt more seemly to leave this unexpressed. Now, when one party is forced to say to him self regarding the other “You poor devil, what have you to give?*' this formula has no bearing. There was nothing which he could give to me, the minister of State. What he had was something which I found extraordinarily attractive as a private person. He was one of the most intellectual and amiable men with whom I have ever had to do, ambitious in the grand style, and by no means a republican. His sympathies were unmistakably national and monarchical, and he aimed at the establishment of a German empire. Here, then, we had a point of contact. Being, I repeat, ambitious upon a grand scale, Lassalle was perhaps not quite sure whether the ruling dynasty in the German empire was to be that of Hohenzollern or that of Lassalle [laughter], but at any rate he was thoroughly monarchical. . . . He was extremely able and remarkably energetic, and I found it most instructive to converse with him. O ur talks lasted for

14

LASSALLE

hours, and I was always sorry when they came to an e n d . . . . As to negotiation, there was none, for in truth I found it very difficult to get in a word edgewise [laughter]. He bore the whole burden of the conversation, but most agreeably, as anyone who knew him will agree.......... I am sorry that our respective positions made prolonged association impos sible, and I should be only too delighted to have a man of like genius as one of my near neighbours in the country [laughter]. William H arbutt D awson, in German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle (1888) Lassalle . . . was a sort of political Mahomet, the attachment of whose followers was not without a fanatical side. Genuine affection implies, not only lovingness in the subject but lovableness in the object, and, let us be as indulgent as we may, Lassalle’s was not a very lovable nature. In private life none had so many admirers with so few true friends, and in public life no one, perhaps, received so much adula tion and caressing and so little real love. . . . I f . . . Lassalle was not so inordinately ambitious as people try to make out, he was inordinately vain. This was one of the most striking, though at the same time most harmless, traits in his character. His vanity was of the kind that neither hurts nor offends. Vanity seemed natural to him as it is to the peacock, and if he had been less vain he would have been less interesting. . . . W hat was i t . . . that gave Lassalle his marvellous power as a demagogue? Let it be remembered that the subjects on which he spoke were for the most part scientific and technical. His addresses dealt largely with dry theories of political economy, which often have little interest for the educated, and might be expected to have still less for the uneducated. Eloquence, enthusiasm, and deep earnestness account for a good deal of Lassalle’s success, but all these advantages in lids favour would have failed to win the masses had he not joined to them a great qualification which dis tinguished him from all popular orators of the day. This was

TRANSLATORS»

PRELUDE

15

his rare capacity for presenting scientific truths and theories in such a form that they could be “ understanded of the people” . His speeches never assumed prior knowledge. He took up a subject at the beginning, discussed and examined it thoroughly, and only left it when he had reached the logical end. . . . He hardly ever spoke for a shorter time than two hours, but he once reached four hours. This was at Frankfort on May 17, 1863. . . . His figure stands forth upon the canvas of modern history clear and prominent with its light and shade, its attractive and its repellent features. ‘‘He is great” , says Emerson, “who is what he is from nature, and who never reminds us of others.” Tried by the test, Lassalle must clearly be awarded the laurels of greatness.

E duard Bernstein, in Ferdinand Lassalle as a Social Reformer (1891), translated by Eleanor Marx Aveling (1893). Lassalle no more created Social Democracy than any other man. We have seen how great were the stir and ferment among the advanced German workers, when Lassalle placed himself at the head of the movement. But even though he cannot be called the creator of the movement, yet to Lassalle belongs the honour of having done great things for it, greater than falls to the lot of most single individuals to achieve. Where at most there was only a vague desire, he gave con scious effort ; he trained the German workers to understand their historical mission, he taught them to organise as an independent political party, and in this way at least accel erated by many years the process of development of the movement. His actual undertaking failed, but his struggle for it was not in vain ; despite failure, it brought the working class nearer to the goal. The time for victory was not yet, but, in order to conquer, the workers must first learn to fight. And to have trained them for the fight, to have, as the song says, given them swords, this remains the great, the undying merit of Ferdinand Lassalle.

i6

LASSALLE

E lizabeth E. E vans, in Ferdinand Lassalle and Helene von Dünniges, a Modem Tragedy (1897) Lassalle possessed the faults, as well as the virtues, of a strong character, together with weaknesses which appertain to feebler natures. He was exceedingly obstinate and dic tatorial, unable to bear the slightest opposition from his co-workers, or to see any glimpse of reason in the arguments of his opponents. He was very vain, and therefore open to flattery of the grossest kind ; he was disposed to curry favour with persons in office and in high places, in order to obtain their recognition of his plans and purposes ; and, finally, he was strongly influenced by women. But, on the other hand, he possessed many admirable characteristics ; he had proved himself bold and tireless in the people’s cause ; and even if personal motives and a false estimate of the consequences of his agitation influenced his conduct, still, his coming forward as he did was brave and noble ; and his party should hold his worthy service in grateful remembrance. G eorge Brandes, in Ferdinand Lassalle (1910) His attractive personality displays an inward inconsistency which is often noticeable in the case of prominent intellects. By instinct, and as a result of his first principles, Lassalle was a worshipper of intelligence, of reason, and a passionate opponent of and scorner of public opinion and of numbers. O n the other hand, by conviction and as the result of his political and practical principles, Lassalle . . . was a most decided champion of popular power, a persistent and suc cessful supporter of universal suffrage, and a pioneer in the service of democratic power such as history had never yet seen. An intellectual aristocrat and a social democrat! The human heart may contain yet greater contradictions than these, but not without loss can they form part of a m an’s disposition. The phenomenon that here meets us is, in the world of thought, precisely that contrast which was out wardly apparent when Lassalle in his dandified clothes, his

TRANSLATORS’ PRELUDE

17

fine linen, and his patent-leather boots, spoke formally or in formally among a number of grimy, horny-handed mechanics. With regard to social questions, he has seen into the future to a point beyond any that we have yet reached, and so far he belongs, not to the present, but to the future. Beneath the political and social surface of Europe is fermenting a great and comprehensive idea which many years ago Lassalle announced to a few thousand men, and which is now [1910] supported by four millions of German voters—the idea that our present economic system cannot be maintained, that it must be remodelled, and that in place of the domination now supported by brutality and injustice, conditions must supervene under which our accumulated and as yet untried economic science can be used in the service of liberation and order; and the fact that this has become a universal sentiment is due to Lassalle more than to any one else. Nature had endowed Lassalle with great and fine capaci* ties ; she had given him a will of Spartan strength, intellec tual and oratorical talent ; like a youth from Athens of old, he had the bow and the lyre. But from the harmony of these great gifts arose a character unequally developed. There was an impure deposit of pride and haughtiness— a “Hybris” , to use the Greek term—and this pride became his ruin. Circumstances granted the opportunity which his capacities demanded in theory only and not in practice. Throughout his life, in freedom or in prison, he was a caged eagle, and under stimulus his force of will rose and became overstrained until it overpowered his other abilities and destroyed the equilibrium of his nature. O ther men might die of undue greatness of heart. Lassalle died of undue greatness of will, but this will or self-confidence, excess of which caused his death, had at the same time maintained him throughout his life. He stands in history as a monument to will-power. The romantic school had found employment for their self-confidence in caprices and tricks of humour. The revolutionary political school satisfied their self-con fidence in a struggle for freedom conducted with genius, but necessarily without political purpose. Lassalle’s selfB

i8

LASSALLE

consciousness obliged him to provide within this period a great and memorable example of personal energy, dispersed and concentrated in a manner wholly characteristic of him. For these reasons all that he has done will ever arouse an interest which is purely human, and partially independent of scientific considerations. E mil L udwig, in Bismarck, the Story o f a Fighter (1926) At that time Bismarck had no rival in Europe for intelli gence. . . . Only in Prussia was there yet another political genius. His name was Ferdinand Lassalle. . . . It was the magnetism of genius, nothing else, that drew Bismarck and Lassalle together. Massive and heavily built both in body and m ind; a dome-shaped head; a man who had come to the front slowly, looking forward to many decades, . . . curbing imagination by realism, weighing words and preparing deeds, reckoning by preference with magnitudes rather than with ideas—such was Bismarck . . . on the threshold of his great work, when he was on the verge of fifty. Slender, elegant, quivering, like an Arab steed but half broken in, was the m an of Semitic stock who confronted him ; a man with a long and narrow head; scintillating; not yet forty, but approaching the end of an impetuous career; a great draughtsman, whose formative impulse exhausted itself in dazzling sketches ; an imaginative and thoughtful man ; an escapee from the school of ideas into the world of deeds ; fighting even in this world of deeds with words rather than blows ; his eyes directed towards the future—such was Las salle. . . . Lassalle was a Jew, a man without nationality, who had scrambled his way upwards in a strenuous youth, who fought his class and was in conflict with his heritage, his emotional nature inflamed for the cause of the nation to which he did not belong by race, and for the cause of the class to which he did not belong by station. . . . Bismarck was compelled to life-long service by the career he had chosen; he had chosen to serve the king, whereas

TRANSLATORS’ PRELUDE

*9

Lassalle had chosen to serve the many. Although Bismarck dwelt in a strong castle, he always heard over his head the footsteps of a man under whom it was his destiny to live. Lassalle heard no one over him, but his castle was built of air, and his nerves trembled more in the wind of the future than through the frictions of reality which were so deadly to Bismarck’s nerves. While both men were of the artistic temperament, the elder was playing chess against the other powers, whereas the younger was rather an actor contemplating his own performance. T hat was why Bis marck was influenced chiefly by ambition, Lassalle by vanity. Thus it was that Lassalle could luxuriate in successes and prospects in which he visioned a more distant future than Bismarck could see; whereas Bismarck wanted less, but wanted tangible realities, and therefore he cultivated patience. T hat was why Bismarck lived twice as long as Lassalle, and also why Lassalle was richer than Bismarck in moments of happiness. No sooner did they meet, than they recognised one an other’s worth before that worth had become known to the world. O tto R ühle , in Karl Marx, criticising Marx’s criticism of Lassalle (1928) Marx’s judgment . . . contained no syllable about the enormously important fact that Lassalle . . . had actually appeared in history, and, at this particular epoch, had conjured the labour movement out of the ground. It is of minor importance how much in Lassalle’s theory and in his method of agitation may have been sound or unsound, how much he may have borrowed from Bûchez, taken over from Malthus, understood in Ricardo, or misunderstood in Marx. The decisive thing was that he succeeded in marshalling the proletariat in a politically independent formation upon the battlefield of history. Mehring rightly points out that at a later date, when the proletarian movement began to develop in the United States, Engels, writing to Sorge anent the

20

LASSALLE

criterion of achievement in a particular historical situation, said : “ The first great step when, in any country, the move* ment makes its appearance, is the constitution of the workers as an independent political party, no m atter how, so long only as it is a separate labour party” . T hat was the sense in which Lassalle acted; and, in that sense, Lassalle*s achievement was a historical deed of supreme importance.

PART

ONE

H ow docs m an grow? From below upw ards, or from above dow nw ards? From below upw ards ! For below they are all alike; but above, one is greater and another is smaller. Jewish Apophthegm

CHAPTER

ONE

THIRTY THOUSAND NEW CITIZENS At the little town of Loslau in the district of Rybnik in Upper Silesia, the schoolmasters were not of the persuasion of Pestalozzi, but of that of General Zieten and Marshal Schwerin. Twenty years after the publication of the famous educational work Leonard and Gertrude, their principles of instruction were still based upon the drill-book, the Lord’s Prayer, and the guardroom regulations. They were veterans and disabled warriors of Old Fritz, of pedagogy, and of grammar. They taught spelling in accordance with Schatz’s Introduction to German Orthography. They were as thoroughly planted on their feet as a “rocher de bronze” and they ruled with the aid of a cane with which day by day they kept their pupils in order, speaking of their use of the instru ment as “stimulation” , “revelly” , and “ the painful military tattoo” . This school abounded in painful experiences, being thus a school of life ; and they taught the soldierly rather than the civic virtues. In the elementary schools, slaves were trained to serve the lords of the earth, their contemporaries, now being brought up in military academies. “Youngsters exist for the king” , thought the school masters, whose seminaries had been at Torgau, Hohenfriedberg, Kunersdorf, and Leuthen. “For the king” was a euphemism. It really meant “for war”—a view which was not only patriotic but also prophetic, and the prophecy was to be fulfilled during the decade 1806-1815. At Loslau, in the year 1791 “of the ordinary reckoning” , there was born to a certain Feitel Beraun, to his great satis faction, a son. This boy, named Chajjim Wolfssohn, being a Jew, was excluded from the elementary school. He learned Hebrew in the synagogue and German in the street. For the rest, a little Jew living between R atibor and Kattowitz had plenty of opportunities for learning what life meant to him, and of acquiring the art of choosing at the right moment between compliance or defence, obedience or defiance.

«4

LASSALLE

Chajjim, being endowed with excellent powers of observa tion, was thus able even without the elementary school to pick up all the necessary elements of schooling except the “ tattoo” , the “stimulation” , and the “revelly” . For him, thinking and even calculation were rather slow processes, but he could manage them well enough. He grew up to be a good Jew and a good merchant, whereat God Almighty and his father were both duly pleased. He could pray and could keep accounts, and experience taught him that when the former fails the latter is always helpful. In the district of Rybnik, little had been heard of the new rights of man which were being upheld in Paris by setting the guillotine to work in the name of reason and humanity. At Rybnik, therefore, the old order of things persisted un challenged, the order in virtue of which the Gojim [Gentiles] ruled badly, and the Jews obeyed badly, each after their kind. Life at Loslau was not luxurious, but was fairly com fortable. When Chajjim was fifteen years of age, Prussia’s misfortunes began. Jen a and Auerstädt were lost; Berlin was occupied; the centre of gravity of the Prussian State moved eastward; the eastern provinces of Prussia became substantially Prussia. Königsberg, Breslau, and Tilsit were the heirs of Berlin, Potsdam, and Magdeburg. Hither streamed from the west the government officials, the refu gees, the turbulent, the freebooters, the windbags, the petty adventurers, and the great political gamesters. The friend ship between Prussia and Russia opened the frontiers, and from Poland and Posen there was an influx of enterprising persons making their way into Silesia. The spring freshets of this disturbed period swept little Chajjim along with them to Breslau. The corpse of the Prussian army provided abundant food for the worms. When in January 1807 Breslau capitulated because the commanding officer, General von Thiele, knew no more about modem methods of war-making than the Loslau schoolmasters knew about modern methods of education (one cannot rule a fortress as one can perhaps

THIRTY

THOUSAND

NEW

CITIZENS

25

rule a class, with the drill-book and the Lord’s Prayer) ; when the disarmament of the Prussian troops was taking place and the army storerooms were being emptied—there began a lively trade in blankets, saddles, and boots; and Hebrews with a keen eye to business were able to help the soldiers rid themselves of their encumbrances. It would seem that these philanthropists (who also hastened to contract for the supply of the French army with meat) must have got a little out of hand now and again, for we find that in May 1808 the French commandant at Breslau had to issue an army order “threatening the usurers with a flogging” . The seat of punishment is mentioned in plain terms, so that one might almost imagine that the general had gained his experience under the Loslau schoolmasters. After the withdrawal of the French, Breslau became one of the most important places in Prussia. It was the centre of all the districts which were striving to reorganise the country, and became a university town simultaneously with Berlin. Tauentzien worked here; and it was here that the threads between Warsaw and Berlin formed a node. Here Chajjim stayed. There is nothing which favours lavishness more than does insecurity of life, a labile political situation, one which opens the door to every hope and excludes no possibility. In such circumstances, the morrow must take care of itself. There is neither poverty nor wealth. Values fluctuate and cease to have a stable foundation. Now that Europe had become one vast battlefield, a sword was just as solid a possession as a house. The gold galloons of the uniform of one of Napoleon’s officers were worth as much as a landed estate. Since money had no assured value, it passed readily from hand to hand. Luxury grew side by side with want. Thus, though it is difficult to say who during the years 1810 to 1830 can have been in a position to buy silks, it is certain that Chajjim Wolfssohn sold them. Chajjim, in fact, did well for himself among the vigorous and efficient persons who lived in or visited the metropolis of the border province. More people, more possibilities ! He kept

a€

LASSALLE

his eyes wide open, and was quick to seize every opportunity, however small. When old Feitel received a letter from Breslau, he greatly enjoyed reading the first three pages. God’s blessing rested on his house ; to read his son’s letters was as sweet as to read the Thora [the Pentateuch]. But the fourth page of the letter was always inclined to put him out of humour. It was sent by his daughter-in-law Rosalie, who had an ungainly handwriting, and a sour habit of mind which prevented her from seeing the funny side of life. Feitel—who was always delighted to note that in his son’s letters, even though the spelling might be at fault, the arithmetic was invariably sound—was naturally annoyed when Rosalie would carp even at her husband’s calculations. For Central Europe in general, the Middle Ages came to an end with the close of the fifteenth century, but for the Jews of that part of the world the medieval epoch lasted well on into the nineteenth. Luther accustomed the Germans to the Hebrew Bible by translating it for them, but the Bible itself did not accustom the Germans to the Hebrews. Whereas among British Protestants an acquaintance with Holy Writ aroused love and veneration for the people which God had singled out for paternal retribution, in Germany there prevailed an antipathy towards a nation which declared that the Messiah had not yet come—an opinion which seemed fully justified to them by their own circumstances. The history of the translation of the Bible, which in all other European countries is the history of the rehabilitation of the Jews, is in Germany a history of iconoclasm, intolerance, fanaticism, and thirty years of incendiarism. Luther gave a book to a populace that had not yet learned to read. The upshot was that these illiterates, pitchfork in hand, plundered the cathedrals and minsters, and fired the seats of the gentry. Never was a book more peaceful, and never did a book have bloodier effects. This Jewish Iliad whose Odysseus was called Moses, its Patroclus being Solomon, and its Ajax being Samson—this Jewish Iliad which came to an end with the

THIRTY

THOUSAND

NEW

CITIZENS

07

crucifixion of the divine Achilles while his mother ThetisMary stood by weeping—was misunderstood. Thus Luther, though he freed the German Christians from Rome, did not free the German Jews from the horrors of the ghetto. He brought about the most remarkable shuffling among the twenty-three upper grades of the feudal society of the Middle Ages, but the Jewish estate still remained the twenty-fourth and the lowest. I t was to two reputed Frenchmen, who were not really Frenchmen, that the Jews owed their deliverance from an unworthy situation. One was Rousseau, the other was Napoleon. Rousseau prepared the way for the great revolu tion by demanding liberty, equality, and fraternity, in the name of the rights of man ; Napoleon ended this revolution by realising its demands. The common fosses in which the myriads slaughtered in his battles were entombed were the most convincing of memorials to an equality whose only defect was that it had to be attained through the gateway of death. Napoleon made men equal by slaying them. Through his instrumentality they became brothers in death ; and he at least set their souls free, since the souls were delivered from the bodies by his musketry fire. He ended the revolution by making himself its emperor. It had known how to deal with kings, but an emperor was too strong for it. The German princes hated Rousseau, the father of the revolution ; but they detested Napoleon, the assassin of the revolution, no less. This inconsistency passes by the name of politics, a word which can usefully mask graver offences than those against mere logic. But (to stick to our Napoleon) the German Jews have every reason to regard the great emperor as their liberator. The fact was that the Prussian government made such a complete job of the war of liberation that it actually freed the Jews. No one who is familiar with the mental state of legislators will be surprised that Lessing, Voltaire, and Moses Mendels sohn had no traceable influence upon anti-Jewish legisla tion. It is true that in 1787 the Jewish poll-tax was abolished, but in December 1789 the petition of the Prussian Jews to

98

LASSALLE

be granted civil rights was scornfully rejected. The storming of the Bastille took place on a foreign meridian, and the Prussian State philosopher Fichte wrote : “The Jews must have human rights. But as for giving them civic rights, I see only one way of doing that, namely to cut off all their heads in a single night and to provide them with new heads con taining not a single Jewish idea.*’ Unfortunately for the Jews, there has always been a scarcity of heads in the world, so that the best thing that could be done was to apply the first half of Fichte’s prescription. This process, also known as a pogrom, had the effect on the Jews of making their children’s heads a little more Jewish than before. Napoleon, meanwhile, had transferred the venue of history from the green tables of the royal council chambers and studies to the green slopes of the battlefields, where decisions were much speedier and far more radical. Unfortunately, the god of history imitates the devil in this, that he prefers to write in human blood. With the blood of thirty thousand slaughtered Prussians, he wrote the edict which freed thirty thousand Prussian Jews. On March n , 1812, the Middle Ages ended for the Jews. They became citizens at the moment when the citizens were beginning the attempt to make themselves rulers of the State. O f the 62,000 inhabitants of the Upper Silesian capital, at least five per cent were Israelites. They wept for joy, embraced one another, praised King and God and Minister Hardenberg ; they jubilated, they prayed, they sacrificed, they sang psalms of joy. One of them was Chajjim Wolfssohn, silk merchant of Breslau, who, in virtue of the new law, took to himself an official name, which he obtained by a slight modification of the name of his native town. In this way Chajjim of Loslau became the Prussian citizen Heymann Lassai. To this handsome name belonged a handsome man, and to this handsome man belonged a handsome sum of money. We cannot speak of the man without speaking of his money, for he himself had the disagreeable habit of talking about money. Lassai kept a very good table, but at meals, as soon as a blessing had been invoked, he would begin a series of

THIRTY

THOUSAND

NEW

CITIZENS

29

pointed observations concerning waste of money, unfor tunate purchases, and stagnant sales. The family circum stances were not straitened, but it was otherwise with their souls ; the family life stood under the sign of the ducat, which brought peace and broke it, and was the cause of intolerable scenes. Human rights can be granted by others, but human dignity cannot. The State can give titles of honour and can take them away, but it cannot bestow honour. The liberation of the Jews had taken place too rapidly. For centuries they had been oppressed, and the ground became unsteady beneath their feet when this pressure was too suddenly removed. In the newly enriched circles of the Berlin and Königsberg Jews there now began a ridiculous imitation of Christian customs, baptism included. Since they regarded Judaism as synonymous with backwardness and lack of culture, they abandoned Judaism. But “Jewry” stuck to them whether or no. They remained what they had been, but became something which they had not hitherto been— hypocrites and upstarts. In Breslau, however, where Jewry was persistently and powerfully recruited from the hinterland, Heymann Lassai found it easy enough to remain true to the faith of his fathers. Somewhere about 1820, Rosalie presented him with a daughter. A few years later, on April 11, 1825, she gave birth to a son. In the midwives’ register at Breslau the date of this birth is given as April 13th. The girl had been born on the i ith, and it was the custom in the Lassai household to make one festival of the two birthdays—on the 1ith. It is, perhaps, a superstition which makes us think that the midwife was more to be relied upon as to the date than the mother (who perhaps was not thoroughly versed in the Christian calendar). Anyhow the boy was given an imposing name, with three syllables to it, a king’s name, Ferdinand. He remained the only son. He was crown prince. These Jews, who in 1812 had from pariahs become citizens as suddenly as chrysalids become butterflies, had the most extravagant hopes, not so much for themselves as for their

S®

LASSALLE

offspring. They looked upon themselves as the foundations and dark cellars on which the coming generations would build upwards gloriously into the sunlight. They had been granted freedom, but to them freedom seemed (as do all gifts) a burden and a responsibility. Their generation had been admitted to freedom ; it had not been free born. They had been nominated citizens, promoted to full manhood, and they looked upon the bestowal as an act of clemency. Thus they came to set the most preposterous hopes upon their sons. Their feeling when they first adopted their new civic names was that it behoved them to be the progenitors of a new generation. Their concern was for the race. Since they had been enslaved, their sons should become masters. The education of their sons suffered in consequence. It seemed to them neither necessary nor desirable to curb the selfishness, the obstinacy, the arrogance of the younger generation. They themselves had been thralls, and they knew that unruliness was appropriate to the master caste; they themselves had been subordinates, and it seemed to them that uppishness was lordly. What could they know of the inward conditions of lordship? They were too optimistic to be good teachers. One day Ferdinand comes home with a bloody nose. This catastrophe almost reduces his father to tears. Not only must the “patient” stay at home from school, but that evening the doctor is called in, and orders a vinegar compress to be applied to the swelled organ. Next day a second doctor is summoned in consultation, to help decide whether Ferdinand may leave the house, and since it is thought that the cold air of his unheated bedroom may retard recovery, his bed is moved into his father’s room. Ferdinand, who is now fifteen years of age, keeps a diary, and that evening he records with satisfaction the evidence of his father’s doting fondness. But he is not free from anxiety. “ I am very much alarmed that my nose may remain per manently swollen. If that should happen, my poor face will be spoiled, but I think that in the long run I should not therefore be greatly troubled. O f this much, however, I am

THIRTY

THOUSAND

NEW

CITIZENS

31

certain, that I should shun ladies* society, for at the sight of any woman the idea would rise in my mind : ‘W hat triumphs you might have had if this accursed accident had never happened*.” It was not his nose which first threatened to interfere with his “triumphs’*. Before he was thirteen, his tutor, looking through his copy-books, found in one of them a formal challenge to a duel. The offended party was one of his school fellows, and the offender was Ferdinand Lassai. The trouble was about a dear little maiden of fourteen, for whose favour the two champions were to fight. The tutor was clever enough to convince this cavalier in search of triumphs that a duel between schoolboys would be universally regarded as ridiculous. Dread of the ludicrous sufficed, where dread of punishment might have been inoperative. The duel was called off. The rivals, zealous rather than jealous, came to a friendly understanding, the one who renounced any claim to the fair maid’s charms being consoled by a liberal supply of sweets and other dainties.

CHAPTER

TWO

STRONG MEASURES Algebra is an Arabic word used to denote the art of trans forming numerical values by conjuring them from one side of an equation to the other. They seem to disappear, apparently turn up again as negatives ; but in reality their values are unchanged. This oriental jugglery writes letters but means numbers. The sign of equality is the rope, and the numbers are the weights with whose aid the rope-dancer keeps his balance. He shifts the numbers to and fro, but all the while the balance remains undisturbed. Algebra is a highly developed Talmudic art, and in the Lassai household it played a notable part. Here it was called ledger and day book, and even God himself (insofar as he had to do with the house of Lassai) made use of this ciphering language. For in 1812 out of the Jew Chajjim there had developed the Prussian citizen Heymann Lassai. Thirteen years later, probably on April 13th, was born his only son, who thirteen years later stUl, in accordance with the custom of the synagogue, became a “bar mizrah” , that is to say a respon sible member of society and a full member of the synagogue. In 1851, and therefore thirteen years later, when Ferdinand was in prison, the reaction nullified his political existence by sending all the radicals to the penitentiary or into exile and thus putting them out of action. In 1864, after the lapse of another thirteen years, Ferdinand destroyed himself. At thrice thirteen years of age, he fell in a duel. This is not mysticism, but one of the cases by means of which life tries to make us believe that it is an algebraic calculation. The equation of life, however, contains too many unknown elements to be solved in any other way than by guessing. Since even a lucky guess is not yet a solution, we may leave this m atter of the thirteens to the consideration of the curious. Anyhow, on Ferdinand’s thirteenth birthday he was the central figure in an important ceremony, the attainment of

STRONG

MEASURES

33

his majority at the synagogue. With this ceremony, a Jewish boy passes from boyhood to manhood, becoming fully adult in all matters of religion. To Ferdinand it was easy enough, thenceforward, to play the grown-up at home as well as in the religious life. His mother was petty, quarrelsome, ill-humoured, and disagree able, with a strong taste for scandal, and her chief trouble was that the most spicy items of information about her neighbours often escaped her. She was a deaf gossip, which means that she was a peculiarly irascible one. People had to shout when they were telling her things which ought only to have been whispered if their full venom were to be preserved. For her favourite pastime, she needed a sharp tongue and good ears, whereas she was only ill-mannered and hard of hearing. H er daughter Friederike was said to be pretty, which meant little more than that the girl was not burdened with brains. In fact, she was stupid enough to write com promising letters, although her lover lived only a few streets away and was apparently more interested in a liaison than in a correspondence. Furthermore, she was so blind as to be unable to see that he was the kind of scamp who makes no bones about showing his sometime fiancée’s love-letters to all and sundry. The brother’s diary throws a glaring light upon the deficiencies in this beauty’s intelligence. The brother, then, so soon as in the synagogue he had acquired the emblems of manhood (the tallith or prayingshawl, the phylacteries or prayer-boxes with their long straps), assumed the vice-presidency of the household. From that time on, the Lassai family comprised the two men, Heymann and Ferdinand, and the two women, Rosalie and Riekchen. The women accepted their subordination without resistance, and the father was only too delighted to note his son’s precocious adoption of hectoring ways. It seemed right to Heymann that Ferdinand should invariably dominate the conversation. Their history has taught the Jews to stand on their own feet when they are still quite young. Their childhood is short ;

34

LASSALLE

need curtails the age of irresponsibility. They have always had to grow up as quickly as possible, this meaning th at they must develop acquisitiveness at a very early age, and must learn that an invincible logic can replace armour and walls. Almost before they had ceased to wear swaddling-clothes, they, being perpetually subject to attack, had adopted the defensive organs of those who are weaponless, namely logic chopping and imagination. They were men as soon as, with the aid of these, they were able to look after themselves. Thus the Lassai family had two presidents and four mem bers. The vice-president kept the minutes of meetings which were often stormy. He was, indeed, the only one of them competent to act as minute-secretary. Although he was a participant, he was well gifted with the power of reflection. He could contemplate himself as one of the actors ; he could look on at the scene in which he was himself playing a part. By the time he was fourteen, he had completely lost the child’s lack of self-consciousness. The simplest way of understanding the lad’s nature is to realise that he lived in front of a mirror. If I might describe a “ too much” as a “ too little” , I should say that he lacked simplicity. “ In this book I propose to inscribe all my doings, my mistakes, my good deeds. With the utmost conscientiousness and uprightness, I shall record in it, not only what I do, but also the motives of my actions. For every man it is extremely desirable that he should become acquainted with his own character. Shall I not blush, when, having done something unjust, I record the fact here? And shall I not blush even more deeply, when I subsequently re-read what I have written? It is with this twofold moral purpose that I have undertaken to keep a diary. F erdinand L assal.” January i, 1840. Ferdinand may, indeed, have had good grounds for blushing if he ever re-read this earliest literary effort. T hat is not so much to say anything against the lad’s character, as

STRONG

MEASURES

35

to emphasise the unsparing frankness of the record. No one need make much to-do about the minor and major misdeeds of a callow youth; but while it is easy to commit such offences, it is hard to report them without illusions. Fer dinand, however, is the faithful reporter of his days and his doings ; of his actions, and of his reactions to the actions of his companions. He has frequent clashes with Riekchen, whose temper has been rendered very unstable by her love-troubles. The mother nags, the father thumps the table, Ferdinand sneers, Riekchen sniffs. On one occasion, when the father is not present, there is an open quarrel between brother and sister. Riekchen angrily defends herself, Ferdinand seizes her by the arm and tries to push her through the doorway. Riekchen^ resists so abrupt an ending of the dialogue. JLÎ2 3 8 • 0 Tears flow down her cheeks; she sobs, thrashes the air, storms, saying : “How dare you raise your hand against your sister?” The mother intervenes, separating the pair. Riekchen rushes off to her own room, throws herself into a chair, screams and howls, stamps and rages—in a word, has a fine fit of hysterics. Ferdinand is quick to realise that unless he takes prompt action things may turn put ill for himself, since his father will soon be back to dinner. He has only a few moments, so he ventures a master-stroke. He bursts into his sister’s room. Foaming with rage, he flings himself on his knees, wrings his hands madly, and then (having made sure that his father is not yet on the stairs, and that the situation can still be saved) he begins to speak in a raucous voice, shouting as if possessed : “O God, O God, grant that I may ever bear this in mind, grant that I may never forget this hour. . . . And you, snake, with your crocodile tears . . . you, . . . ah you shall rue this hour. In God’s name, in God’s name, I swear it! Even should I live fifty or a hundred years, . . . on my death bed I shall still remember ! ! ! Nor shall you ever forget it.” Riekchen is terrified into sobriety, so that she stops weeping and wailing. Alarmed and confused, without another word

36

LASSALLE

she withdraws into a back room. Ferdinand writes in his diary : “Ju st as peace can only be secured through war, so my excessive anger was the means of bringing about tranquillity” . This attack with the aid of the great curse, supported by the kneeling posture of prayer, by wringing of the hands, by appeals to God, by exclamations, by allusions to the death bed; this sudden transformation of a surprise attack into an impulsive outburst of wrath ; the presence of mind with which so outrageous a bluff was staged—fully deserved the success they achieved. War is the last, the strongest, and the most disagreeable of political methods. Lassai was fond of using strong measures, and it was inevitable that this fondness should in the long run drive Lassai into politics. W hat is politics but a perpetual readiness to use the strongest measures against the weakest adversaries? Ferdinand knew this by the time he was fourteen. Fränkel has lost sevenpence halfpenny to Ferdinand at cards. The loser has no inclination to pay, and this is a familiar situation in the political world, where the great powers are accustomed to go to war in order to avoid paying their gambling debts—if the sum be big enough to make war worth while. Ferdinand mobilises his forces : “Look here, I ’ll teach you to play for money and not to pay up. If you don’t pay, I shall claim the money from your uncle, and at the same time I shall tell him that you left his shop unwatched in order to come and play cards with me. Nor shall I forget to tell him that you tried to cheat.” The minute in the diary concludes as follows : “I frightened him so much that he paid me” . Again, his sister threatens to tell tales of him for playing truant at school and spending his time in a billiard-room instead. He writes : “ I needed all my presence of mind and (not to put too fine a point on it) all the brazenness I could command, to outface her” . To-day there is a science much in favour known by the name of psychoanalysis, which trades upon the knowledge

STRONG

MEASURES

37

that the mind has its seat, not in the brain, but in the region of the lower belly; and this science has a very instructive variant, which passes by the name of individual psychology. Both these sciences are able, with the assistance of involved terms such as repression, complex, over-compensation, and the like, to explain certain very simple things. O f course one can explain them also without having recourse to these sciences. Ferdinand’s start in life was an extraordinarily good one ; the boy’s whole environment and all the members of his family had made great headway ; Ferdinand was leader in the race; all we need now is that a psychologist should explain to us why the leader in a race puts on a spurt as soon as he sees his leadership threatened, and then we shall fully understand the boy’s character. But the house of Lassai was not an easy school of life for the growing boy. The mother, being suspicious like all the deaf, was difficult to handle ; the sister, who was perpetually being urged to marry but saw little chance of finding a husband, and who suffered from her ambiguous position without being able to change it, was extremely irritable; the father, eager to see his daughter settled in life, was tetchy and querulous : the whole atmosphere was tense and unrestful. In this household, conversation turned upon two things, money and a ‘‘good match” . To shine, one must be successful as a man of business or as a marriage broker ; and to hold one’s place in the world one must be a good arithmetician and of a calculating turn of mind. Family life was an affair of algebra or rule of three, and if the nerves made irrational incursions they must cold-bloodedly be put back under control. If you should, in spite of everything, find yourself in a tight place, you must extricate yourself by an egg-dancing movement, by elaborate sophistry, and make your retreat look as if it were an onslaught. In many cases it was enough to react to punishment within twelve hours by falling ill. “ Vexation on account of this chastisement made me quite sick by afternoon. At once he was the loving father again, anxious, much concerned. I had to go to bed with a fever.” His mother could not leave

LASSALLE

his bedside, Riekchen scoured the town and collected all the relatives, and Ferdinand, securely entrenched among his nearest and dearest, won one game of écarté after another, pocketing a penny on each game. When his finances had been sufficiently restored, and when his prestige had been re-established, he would get well again. At a wedding party the bride and bridegroom usually form the centre of interest, but this was mortifying to Ferdinand. He could not bear to play second fiddle, were it but for a day or only for an hour or two. O n all social occasions there was apt to be friction between him and some other guest less well equipped for a combat, the invariable result being that Ferdinand would come off with flying colours, whilst the other would be made to look ridiculous and would be com pelled to sue humbly for peace. Proposing a toast to the bride, he says: “Never shall I forget, Madam, how you looked when plighting your troth. Your soulful eyes, half-opened, half-downcast, glistening with tears which threatened to dim their brightness, a myrtle wreath in your bridal hair, a rustling white satin robe on your charming limbs.” “T hat will do, Ferdinand, you are becoming too poetical !” broke in the father, somewhat late, with mingled admiration and reproof. “A clever fellow that brother of yours, very clever” , said Dr. S. aside to Riekchen. “ O f course he is” , answered the girl, preening herself. This happened when Ferdinand was fourteen years old. He is ambitious ; he wants to shine, he wants to dominate. He can only think of himself as leader, as chief. He thinks of himself as leader, but he does not think much about those whom he is to lead. They are the led, a formless mass ; they are the people whom he will lead. Sometimes it is his “favourite notion” to place himself “sword in hand at the head of the Jews, and to make them nationally independent” . He has scarcely any friends at school, being made not for collaboration, but for command. He speaks of those whom he can order about as his friends, and of those who oppose him

STRONG

MEASURES

99

as his enemies. Persons who obey him blindly are his com rades; those who insist upon their own independence are rascals. He prefers to keep company with people much older than himself, for this tickles his vanity ; and when he hobnobs with those of his own age it is only because he finds them useful. “ I like to associate with Hahn at school, in order to improve my knowledge of human nature.” It is as well that he should see the need for practice in this field, for he is too fond of looking at his own image in the mirror, and his mind is continually occupied with his own pos turings. This handsome, narrow-cheeked, pale-faced fellow, with a small and rather vain-looking mouth, a well-moulded and expressive forehead surmounting the almond-shaped blue eyes, and with an abundant mane of brown hair which he dresses in Byronic fashion, is as much in love with his own features as was Narcissus, and has no eyes for the outer world. Seeing that the eyes of his associates are directed towards himself, he naturally makes himself the centre of his own gaze. These eyes of his are sharp enough to pierce through externals. He sees himself through and through. Thereupon he at once begins to pomade his mind, to brush and comb it, to manicure it, to titivate it, to curl and iron it, and to equip it with the elegant ruthlessness of Byronism. “ I t is a fault of mine that I do not blindly obey my father's orders, as perhaps I ought to do, but instead think them over and ask myself, Why does father tell me to do this? Having done so, I come to the conclusion that my father does not seriously object to my spending a leisure hour playing billiards, and that his real reason for forbidding me must have been to prevent billiards from becoming a passion with me as might well happen in view of my sanguine temperament. But gambling is no longer a passion with me, and can never become this. Consequently I can play billiards without infringing the spirit of my father's orders. When I transgress the letter of this command I do not transgress the spirit, the inner meaning ; I do not run counter to my father's true aims. Whether I am right or wrong in behaving thus, I do not know.”

40

LASSALLE

But as soon as he loses money, he knows perfectly well that he Is doing wrong. Where he finds it so difficult to decide between right and wrong is when he succeeds in winning money. A day comes when his income from écarté amounts to a whole sixpence. O ur keen man of business does not despise small profits ; he computes the risk and the advan tages ; he knows how to make the profits accumulate on his side and the losses accumulate on the side of his adversary ; registers his vote cold-bloodedly, where Riekchen’s loveaffairs are concerned ; and, instead of the young man after his sister’s heart, would prefer to have as brother-in-law one of whom it may be said to be a pity that he comes from Inowrazlaw, but who is greatly to be commended because he “speaks four languages, is of a very rich family, and owns from thirty to forty thousand talers” . So much excited is our Ferdinand about this possible suitor that the two relevant pages of the diary bristle with figures. The “minute-book” reveals to us a young gentleman whose Sabbath is spent as follows. To begin with, he plays six games of billiards with a friend ; then he visits a pastrycook’s ; his next remove is to another place of entertainment, where he has two games of bowls ; then three more games ; then at least three more with another opponent, until he has lost a shilling. After that he goes home, plays écarté with his mother (he likes playing with her when he is short of cash), and wins sevenpence. He rounds off the day with onze-etdemi. “We played for penny stakes. Father seemed a little annoyed that they were so high.” Speaking generally, the father had some ground for dissatisfaction. He had to earn his livelihood, to provide for his family, and on Friday evenings to pronounce the invoca tions. He was Chajjim from Loslau, who sold silks, and entertained fanciful expectations. He was incautious enough to make no secret of his affection for his son, as the embodi ment of his wishes and hopes ; he was foolish enough to beg when he ought to have commanded, and to explain when he ought to have issued his orders. “Stay at home with me, Ferdinand ! What shall I do if you go out? I can’t talk to your

STRONG

MEASURES

4*

mother, for she does not hear well enough. Riekchen is only a girl, and not a very clever one. At any rate you and I can have a good talk together.” Ferdinand, who had learnt from this same father that everything in the world has its price, recognised the value of his own presence, and knew how to turn it to pecuniary account. Since the father showed that he needed the son, the son exploited the father. The father’s demand put up the price of the son’s love. The struggle for predominance between these two was hardly ever fought to the last extremity. The father dared not humiliate the son. But on one occasion they were within a hair’s-breadth of a catastrophe. The cause is typical, and so is the course of the affair. Ferdinand, who likes to be smartly dressed, changes his trousers at midday. But he finds that there are some buttons missing from the ones he has newly donned. Since it seems incredible to him that there should be no one on hand to serve him, he raises a tremendous hubbub. “Take those trousers off and put the old ones on again” , says his father. “ I can’t stand your vanity.” “Oh, well, they’re both of them no better than old clo* !” The father’s rejoinder to this disrespectful answer is given, not with the mouth, but with the hand. Ferdinand replies to each blow with a new citation from the lexicon of arrogance, and finally shouts : “I won’t let any one beat me !” It can well be imagined that this piece of impertinence does not diminish the severity of the flogging. But the reader will find it difficult to guess what the son does next. He promptly ceases blubbering, dries his tears, and makes a rude face. “Whatever my father said, I answered merely with a defiant and scornful smile, which made him want to slap me again. But he refrained.” Obviously, in drawing lots, Ferdinand has drawn the shorter straw. Scorn is only the answering grimace of the subordinate. But he has another shot in his locker. He puts on his old trousers once more, and, without saying another word, goes out into the street, makes his way to the bank of

48

LASSALLE

the Ohle and goes down the steps leading into the water, determined to drown himself. “Ferdinand,” cries the father, who has followed him, and now stands behind him pale and anxious, “what are you doing here?” “ I am looking at my face in the water.” “You needn’t go to school. Gome with me to my office.” Ferdinand nods curtly. This short traverse beside his father from the river-side to the office is a triumphal progress. Ferdinand is in the seventh heaven. He is listening to an imaginary flourish of trumpets, is watching imaginary banners. He is the crown prince. He is the victor. He accepts homage, and in case of need enforces it. He thirsts for recognition and admiration, he is always fishing for approval. In his diary he records with satisfaction the utterance of a schoolfellow in the upper sixth. “Look here, Lassai, you’re a spiteful young rascal, but a clever sort of chap all the same, much cleverer than might be expected at your age. When you are five years older, the world won’t be able to put up with you any longer.” The five years’ limit was not greatly exceeded.

CHAPTER

THREE

APPLIED T R IN IT Y The two worlds whose business it was, for the nonce, to put up with the boy, were the home and the school. To speak of his home means to speak of Ferdinand, who ruled it, who was its substantial content and meaning, and around whom it circled. To speak of his school means to speak of the teachers who ruled that institution. Although while he was still no more than a growing lad his hand lay heavy on his family, at school he was subor dinated by the school discipline. Compliance with its rules was felt by him as a disagreeable compulsion. The need for compliance with its regulations was a menace to his self esteem. Authority had him in its grip, and he reacted by defiance, arrogance, and laziness. H e was able to rule in the household of a merchant who had a wife and a daughter and a partner fourteen years of age. But at school he was tied and gagged ; he was only a fifth-form boy who had to do what he was told. When he came home from school to the midday dinner, when he unstrapped his books and flung them into the corner, he was conscious of being able to hold his own with his parents, whose respect for this pupil of the Talmudic college was bred in the bone. The father’s thoughts turned back sentimentally to his own impoverished childhood, when the wealthier Jews of the little town regarded it as a great honour to have a young student of the Talm ud as daily boarder, and if he married the daughter of the house so much the better. Among the Jews, learning is the only title to nobility. Ferdinand could write in the Greek alphabet, and this was obviously akin to the Hebrew. Ferdinand could read Homer, who had written in the Ionic dialect of Asia Minor, and the neighbours of the Ionians had spoken Hebrew. Aphrodite had been bora in Cyprus, and from Cyprus to Jaffa was but a step. From Adonis, the Greek

44

LASSALLE

god, to Adonai the Lord God of Sabaoth was an easy transition. The humanism of Friedrich August Wolf, Winckelmann, Lessing, Herder, and Humboldt had discovered the Hellenes —and the Jews. Greece had been born again, and out of the ghettos the Jews had been resurrected, in both cases in the name of humanity. People spoke of “Hellas” , but Pales tine was tacitly included. The gymnasium became the school of the humanities ; the tongues of classical antiquity formed the centre of the humanist scholastic program ; and the sons of the ancient Jewish people were now repeating the lessons their fore fathers had pattered two thousand years ago—they learnt Latin and Greek. Humanism was love for classical antiquity. The Jews were a part of classical antiquity. From the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards, the leading spirits among the Germans had been engaged in a cult of classical antiquity ; at the universities, professor ships of Hellenism had been established ; a vigorous revival of classical lore was in progress. But then, in 1824, Friedrich August Wolf and Lord Byron died. Wolf was the last champion of spiritual Hellenism; Byron was the first champion of political Hellenism. In 1824, the Grecian music was punctuated with drum-taps and rifle shots. In 1824, Greece, which had been an object of en thusiasm, fantasy, and philological study, became a country like any other on the map. The birth of modern Greece was the death of Hellenism. A new Balkan State came into existence, and another illusion was shattered. From about 1830 onwards, the professorships at the German universities passed into the hands of the second generation ; and in the gymnasia there were already by 1840 many teachers who must be termed the epigones of humanism. No further epochmaking discoveries were being made in the field of classical letters; the university professors had systematised their teaching, so that it could now be undertaken by persons of third-rate intelligence. Humanism, which had been a

APPLIED

TRINITY

45

fine art, had become a rule-of-thumb occupation for small men. One of the teachers at the Magdalen Gymnasium in Breslau had died. The headmaster delivered the funeral oration. He spoke of the “ true Greek’* who had just passed away. This true Greek had been a little, crippled school master, but he had written a fine book on the syntax of Herodotus. In accordance with the prevailing doctrine, wherein Hellenism consisted in a mastery of Greek grammar, the title of the deceased schoolmaster to be regarded as a Hellenist was incontestable. There was a flaw in the argument, but it was regarded as sound at the gymnasium. Under this sign the pupils were taught Greek language and literature. The “true Hellenes” were a dwarfed posterity of Hum boldt, Voss, and Hölderlin; they were stipendiaries, whose only share in Hellas was a bookshelf containing cheap editions of the classics and the commentators. Pedagogy was a Greek word ; and the knowledge of a few Greek words sufficed to entitle one to be styled a pedagogue. This was not humanism, it was not even philology or pedagogy; it was merely a vestige, an almost exhausted heritage. What forty years before had been vigorous and full of meaning, and had been organically interconnected with the whole of human life, had now become a method, a routine for teachers, and a weariness for the pupils. The school did not educate, it merely disciplined. The instruction at the military academies was said to be “humanistic” when the cadets had mastered the fifth de clension in the Latin Grammar and had made fair headway among the irregular verbs. Ferdinand Lassai had more taste for the argumentation of the sophists than for this grammatical drill: he found it more amusing to let his intelligence roam among complicated logical problems than to stay on the drillground and work at the rules of syntax. The child of the Talmud had much more of the spirit of Anaxagoras or Plato than had the “ true Greeks” who had passed

46

LASSALLE

an examination qualifying them to become higher-school teachers. The dead schoolmaster whose praises the head had sung, was for Ferdinand not so much a Hellene as an evil demon who had plagued him with the irregular verbs, had been nothing more than a crippled policeman, a guardian of the dubious treasures of a dead grammar. In his mind's eye, when the chief let fall that unhappy phrase about the “ true Greek", Ferdinand pictured the dead man as he would have looked with his misshapen form among the naked Greeks at the Olympic games, and he bit his lip till the blood came. At school next day the dead teacher’s place was taken by another Hellene, who came from Glogau, and continued to teach Greek after his predecessor’s manner. Ferdinand, who was used to playing first fiddle at home, found it hard to stomach that he should make so poor a show at school. He was asked there to display what was called “positive knowledge" ; the sort of stuff which, with a little industry, boys of no talent could furbish up. He was talented, but idle. His knowledge was not positive; it was fanciful, im provised. Real knowledge is not of the improvised order. He quoted with approximate accuracy, and could give a good translation of the spirit of the original; whereas the drill-book demanded accurate quotations and literal trans lations. “ It amazes me that some of my schoolfellows who, though I myself say it, are greatly inferior to me in talent, capacity, genius, power of judgment, understanding, wit, should nevertheless get good reports." The youth whose parents made him feel that he was the embodiment of all their hopes, found it very disagreeable when his schoolmasters made him feel that he did not come up to their expectations. He suffered the most humili ating reverses, and, being of a stormy temper, and unable to accept them meekly, he raged against fate. Unexpectedly transferred from the Reform Gymnasium to the Magdalen Gymnasium, he did no better at the new school than he had done at the old. He promptly came into collision with his Latin master, whom he annoyed by his impertinence, and

APPLIED

TRINITY

47

who treated him with contumely. Hence the following entry in Ferdinand’s diary : “At this moment I could have drunk his blood” . When he gets a bad report, he quotes (and, of course, misquotes) that verse of Ovid’s in which the poet, banished to the shore of the Black Sea, relieves his feelings by writing : “Here I am called a barbarian because the barbarians do not know how to value me” . He writes as caption to the report: “Dichtung und Wahrheit” (Fiction and Fact). We may interpret this as meaning that Ferdinand regards his schoolmasters as persons who are chary of fact and are writers of bad fiction. It would seem that the masters thus reported on by their pupil as unsatisfactory, retaliated by describing the fifth-form boy as “unsatisfactory” in their reports—a tit for tat which was to have a lamentable sequel. Ferdinand, who does not believe that his father will be able to distinguish the small modicum of fact in the reports from the malicious fiction, thinks it expedient for the sake of domestic peace to forge the signatures which his parents are supposed to attach to these reports as testimony to their having seen them. He is disinclined to expose himself to the discomfort which may arise if his ill-success at school be comes known at home. He does not wish to endanger his domestic prestige. He therefore decides that his school life is a private affair, with which his parents have no right to interfere. At Easter 1840 the head gives him a bad report. Ferdinand protests. “ I am sure I don’t know, Sir, what I have done to deserve so bad a report.” “You must leave it to me, Lassai, to decide what are your ‘deserts’. By the way, I should like to know why, when you bring the reports back, they are always signed by your mother instead of by your father.” “Because my father is often away, Sir. Besides, he signs them sometimes.” “Sometimes?” replies the head. “ Look here he signed only one of them, and that was a year ago. Has your

4«

LASSALLE

father been away for a whole year, or is he always away when you happen to get a bad report?” “No, Sir. But even when he is at home, he often gets my mother to sign the report.” “ Is that so? Let me tell you why. I t’s because you only show the report to your mother, and never to your father. Well, that’s against the rules. Your mother’s signature is worthless.” “You are mistaken, Sir, for my mother has a power of attorney!” answers Ferdinand defiantly. At least, that is what he would like to answer, but does not dare. He in scribes it in his diary as the repartee he had “thought of making” . We understand why, contrary to his usual custom, he suppresses this “ bon mot” , when we read the last entry in the minutes of the conversation : “The man did not know that my masterstroke had been not to show the report to any one” . Ferdinand thinks it as well to keep this fact to himself, since knowledge of it might have annoyed the headmaster. The latter, therefore, gets his way, and next morning Fer dinand brings back the report duly signed by his father. The comment in the diary runs: “ Signed by my father, that is to say by myself, for I, in case of need, am father, mother, and son” . You may regard this rather frivolous and certainly punish able persiflage about the Trinity as witty or as impudent or as silly. No m atter which, for, even as do the Gospels, it terminated in a sort of Ascension. The headmaster did not like Ferdinand’s methods, and Ferdinand did not like the expression used by the headmaster to characterise these methods. Ferdinand left school suddenly. It was a departure so effectively speeded by the school authorities that without exaggeration it may be called a “flight” . This Trinitarian doctrine of his was something which, were it only on the metaphysical plane, unfitted him to become a “ true Hellene” . It belonged to a different mythol ogy. Besides, Lassai had acquired his learning, not so much during school hours as out of school hours, when he had

House iu Breslau where Lassalle was -boni

Lassalle as pupil at the Leipzig Commercial Academy After a picture in the possession of Professor Gustav Mayer

APPLIED

TRINITY

49

studied business methods. In school he had learned little; out of school he had learned a great deal. He had very vague ideas concerning the language of Homer, but he knew all the tricks and turns of business life. He made a mental comparison between the poor school masters, the guardians of classical antiquity, and the wealthy merchants of the business quarter. The former lived in lodgings, in the garrets of the great houses which belonged to the latter. Since Ferdinand was hungry for power, the outcome of his meditations was a transfer from the school of the humanities to a commercial academy.

CHAPTER

FOUR

COM M ERCIAL ACADEMY In the middle of May 1840, Heymann took his son to Leipzig and entered him as a student at the Commercial Academy there. A hunt was made for lodgings which would suit Ferdinand’s tastes, and the desired rooms were at length found. They cost 400 talers instead of the proposed 250. The son, however, was so delighted with the place that the father at length agreed to pay the extra 50 talers. Only 50 talers, for Heymann’s paternal tenderness did not prevent his bargaining until the price was knocked down by 100 talers. Ferdinand might well draw the inference that he could learn more about commerce from his father than at the new school ! August Schiebe, Lassal’s new headmaster, was thoroughly efficient, and was a man of upright and straightforward character. Having a strong bent of his own, he taught an honest commercial science. He had an inclination to enforce strict discipline, and an antipathy for the “windbags” of Berlin; he insisted upon order in class, and demanded un conditional obedience. In fact, his love of discipline was stronger than his love of justice, so that he was only just at intervals. He was wont to say that when school hours were over he would beg pardon on his knees for his injustice, but that during school hours he must always insist upon having his own way, even if it were an unjust way. (Some, of course, may hold that there is a serious flaw in a justice which is only manifest exceptionally.) Still, though he made a little god of himself, he was not often an angry one. His mind was full of the science of commerce, and he believed that commerce itself was only the application of this science. But commerce is the application of instincts which are not necessarily either scientific or markedly honest. The essen tial thing about these instincts is that they shall be powerful and unbridled. Now, his pupil Ferdinand Lassai had instincts which were

COMMERCIAL

ACADEMY

51