Key Concepts in Feminist Theory and Research [1 ed.] 0761969888, 9780761969884

This original and engaging text explores the core concepts in feminist theory. This up-to-date text addresses the implic

337 93 36MB

English Pages 222 [248] Year 2002

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

Introduction

Concepts: Meanings, Games and Contests

Equality

Difference

Choice

Care

Time

Experience

Developing Conceptual Literacy

References

Index

Citation preview

University L1brane:') Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 152 13-3890 •

. .

W\THDRAWN CARNEG\E MELLON

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2020 with funding from Kahle/ Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/keyconceptsinfem0000hugh

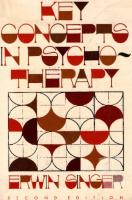

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMINIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMINIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

C HRISTI NA HUGHES

SAGE Publica ti ons London • Thousand Oaks • New Delhi

J.J Firs[ published 2002

•

r

1

All rights reserved. No part of this pub hcacion may be reproduced. stored in a retrieval system, rransmi tted o r utilized in any form or by any means, elecuonic. mechanical. photocopying, recording or othe rwise, w ithout permission in wnung from che Publishers. SAGE Publi cations Lrd 6 Bonhill Street Lo ndon EC2A 4PU SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Te-l ier Road Thousa nd Oaks, Ca lifornia 91320

SAGE Publications Lndia Pvc. Led 32, M- Block !v1arkec Greater Kailash - I

New Dellu 110 048 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A cata logue record for this hook is avai lable from rhe British Library lSBN 0 7619 6987 X 0 76 I 9 6988 8 ( pbk) Library of Congi:ess control number Typeset by 1'1ayhew Typesemng, Rhayader, Powrs Printed ond buund in Grear Britain hy The C romwe ll Press. Trowbridge, \'{lilts hir.'t. Therefore within the discussion of each of the concepts you will find commentary on, for example, libera l, cultural, materialist, postmodern, poststruc-

tural and postcolonial feminism. In addition, and somehow, theory is often vie\'led as detached from empirical research. One either 'does' theory or one 'does' research. Moreover, there is another form of detachment chat operates across this binary. This is that theory is abstract and empirical research is concrete. Because of n1y concerns about these kinds of false separation, you will find interleaved with in the discussion of the varied conceptualizations of equa lfry, difference, choice, care, ti1ne and experience a number of

6

KEY C ONC EPTS IN FE M I NIS T TH EORY AN O RE SEARCH

i11 usrra ti ve case studies. These are drawn from contem pora ry research in the fields of education, employment and fa n1ily and have been selected to concretize the mo re abstract nature of the djscussion . As I am primarily concerned to illustrate how concepts are applied in different forn1s of research J mainly focus on the methodological approaches and theoretical fra1n ev.rorks of these case studies. This allows us to understand the ' results' of research with the necessary contextualization of how these results were obtained and theoretically framed. Finally, as a text focused on developing a form of literacy, [ have included suggested furth er readings. This text provides an introduction a nd a n overv iew of the central issues of meaning, as J see it, in the varied definitions of femi nism's key concepts. The further readi ng has been selected to provide examples of work that can build on t he n1aterial that has been presented here.

Conceptual Concerns

Any text is built o n some kind of theoretical or conceptua l fra mev,ork that may o r may not be made explicit. This places the knowledge presented in a broader episternological and ontologica l field. This further a ll ows us to judge its clain1s and justifications. C hapter 1 therefore outlines the field of language theorizing that has in formed my own development of conceptual literacy. A key point to note here is chat this review is necessarily selective because it is based on what has been personally re levant in terms of my own lea rning journey. In developing your own conceptual literacy other t heorizations may ,veil be equally if not more relevant. As part of opening up rather than closing down, therefore, this cha pter provides a useful starting point to w hich funher theore tical fran1 eworks might be added . Chapter 1 includes a nurnber of issues related to the analysis and theorizatio n of multiple meaning. I begin by discussing Derridean notions of diffe rance and a nal yses of meani ng that focus o n language duali sm . I next turn to Wittgenstein's analysis of language ·with particu lar attention ro his conceptualization of la ngunge ga mes. This is co illustrate the place of context as giving m eaning to specific discou rses within la nguage. Finally, I explore rhe politics of conceptual contestarion. Here I illustrate the cond itions for conrestatio n in tenns of Conno lly's ( 1993) ana lysis of cluster concepts. In addinon, I discuss how conresrarion may masquerade as a simple issue of accurate

INTRODUCT ION

7

description that requires the correct indicators. However, as Tanesini (1994) comments, such descriptors also invoke particular judgen1ents about what is warrantable knowledge that have a justificatory role in tenns of how a field of study should proceed. ln these ways a particular field changes direction or extends its purview both in respect of its empirical and poliitical concerns. One of the consequences of the changes that arise fron1 debates about what cou.nts as adequate ways to proceed is that there is a tendency that post-hoc analyses and thus the veracity of earlier work are primarily read within the terms of these later debates. My concern chat a ny development of conceptual literacy takes account of situating meaning within historical and cultura l contexts is therefore taken up in Chapter 2 by illustrating how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century feminist theorizing of equality drew on Enlightenn1ent ideas of liberalist rights. ln Chapter 2 I explore cwo basic conceptualizations of equality. These a re equality as sa 111eness and equality as difference. In respect of equality as sameness I explore the problems of measurement that are cen tral to such conceptualizations and the policy and legislative outcon1es of rightsbased equality arguments. [n respect of equality as difference I focus on the centrality of motherhood to such conceptualizations and illustrate the varied meanings of this in terms of the eighteenth-centu ry writings of Wollstonecraft and more contemporary Italian feminists ' conceptualizations. Because it is becoming a neglected area, my final concern in Chapter 2 is to discuss n1aterial inequalities. Here I speci fically focus on Fraser's (1995) theoretical conceptua lization through her analysis of the politics of recognition and the politics of redistribution that are part of post-socialist politica I Ii fe. As will be evident from C hapter 2, it is impossible to talk of equality without invo king issues of difference. In Chapter 3 I explore a variety of conceptualizations of difference. These include difference as sameness, identity differences, sexua l difference, postscructural and postco.lonial analyses of difference. Difference has, of course, been of enormous importance to fe1ninis111 with the consequence that there is a plethora of writings that could be drawn upon to illustrate its meanings. The question for any acade1nic or student, then, is 'How does one organize and n1anage this wealth of material?' I begin Chapter 3 by comparing rwo conceptual schema of difference (Barrett, 1987, and Evans, 1995) . One of n1y purposes here is to illustrate how fen1inists approach a field as rich and diverse as difference in terms of the imposition of alternative organi1..ing fran1eworks. For exan1ple, Barrett separates experiential, sexual and positional difference and draws up her framework of three key differences accordingly. Evans draws on particular schools of

8

KEY CO N C EPTS IN FEMI NI ST THEO RY AND RE SEARCH

thought such as cultura l, liberal and postmodern fen1inism as underpinning her three key differences. I continue the discussion in Chapter 3 by exploring t~e key differences through a concern witb conceptualizations of group di ffe rence, deconstructive a pproaches and postcolonial theorizing of multi-axial locationality. Chapter 4 ex plores the concept of choice within a broader fra mewor k of agency and s trucnue. This enables me to situate conceptualizations of choice within debates about these two concepts. 1 offer two conceptualizations of choice. The first is that of rational choice. H ere I illustrate how ra tional choice most closely fits with common-sense, everyday conceptualizations a nd is also central to economic theory. By way of critique I explore feminist economists' analyses of ra tional choice theory in tern1s of its predominant assum ption of agentic, rational personh ood. l then outline poscstruc tural conceptualizations of the choosing subject. These focu s on the processes of sub jectification through keeping in s i1nultaneous play issues of mastery and sub1nission . Whilst postscruccural theorizing is critical of humanist conceptions of personhood, the primary aim is to go beyond the agency-structure ' pingpong' (Jones, 1997) tha t has been a central feature of much theorization in the socia l sciences. Thomas (1993) suggests that care is primarily an en1pirical rather than a theoretical category. H er point is in1portant beca use it highlights ho,.., terms a re conceptualized through the theoretical framewo rks within w hich they a re placed . For example, within sociologica 1 fra n1eworks of ca re giving and care receiving, care has mai nl y been imbued with nega tive n1canings. Within some philosophical a nd psycho logica l writings, and partic ula rl y those of care ethicists. care takes on n1ore positive evaluations. Care is a lso interesting because in some do mains the en1pirical facets of care giving and receiving are renamed. Jn employ111ent contexts, for example, caring is redefined as service or support (Tronto , 1993). H o,vever, one idea recurs. That is that care is primaril y ,vomen's responsibility. In Chapter 5 r explore these mea nings of care through an a nalysis of its economic character in both fan1ily a nd employmcn r don1ains and its ethical in,plications for a deconstruction of rights-based d iscou rses . A conceptualization of ca re as economic has enabled femi ni sts to rename care as work w hether this is unpaid work or paid work. A conceptua lization of care as an ethic has facilira red a crit ique of individualise righ ts a nd associated policies that contin ue to neglect a further centra l featu re of care. This is that we a U need care and we are all equally capable of ca re giving (Sevenhuijsen, 1998). Ti,n e i~ femini sm's latent concept. It is fo r this reason that Adam ( 1989 ) was able to write a n a rticle illustra ting why feminist social

INT RO DUCT IO N

9

theory needs time. Tin1e is so imbued in our everyday language that we most often fai l to notice its expansiveness. When we do we tend to focus on clock-time as the a ll -encompassing only time. ln C hapter 6 1 explore three aspects to conceptualizations of time. The first is the linear time of the clock. T his is the most predominant conceptualization of rime in social theory and can be found in a body of research that ranges from historical analyses to adult develop1neot theories to work-family balance policies. Feminist research has primarily referred co linear, clock rin1e as 1nale time and has contrasted this with fema le time. Female time arises from won1 en's relationship co the reproduction of fa1nily and organizationa l life. It is relational and repetitive as tasks, such as feedi11g, cleaning or counselling, regularlr interrupt the linearity of the clock. I next turn to analyses of cime that are concerned with the developn1ent of the self and I outline here conceptualizations of time chat view the past, the present and the future as sin1ultaneous. For example, I discuss issues of authenticity and the role of time in creating a sense of the conci11uous self. Finally, 1 turn to issues of time- space relationships. Here l particularly focus on Grosz's (1995) analysis of the body and Kristeva 's (1986) conceptualization of feminist politics that both incorporate issues of time, space and identity. Arising from feminist con sciousness-raising and summarized within the phrase 'The personal is the political' experience is central to feminist policies. Experience also fo rn1s the cornerstone of empirical research as the very stuff of narrative and interview. In Chapter 7 1 discuss the development of standpoint theory from its original conceptualization in the late 1970s to the present. Standpoint theory originally posited that rhe experiences of those who were positioned outside the don1inant order gave rise to a more adequate, even superior, view of dominant social relations. Identity politics and postmodern theorizing subsequently raised significant questions about whose experience was being used as the normative standard and whether experience could have such a fixed, ontological status. By focusing on debates that surround standpoint theory this allows me to illustrate the theoretical roots of sta ndpoint theory in materialist feminisn1 and rhe impact of subsequent debate in developLng alternative conceptualizations, and politics, which surround experience. Given the centrality of experience to feminist epistemology I also discuss ferninist debates on objectivity and the role of the personal in feminist theory and research . Chapter 8 forms the concluding chapter to the text. I have one primary purpose here. This is to offer ways in which conceptual literacy can be further developed. As will be clear, .my pri1nary purpose in writing this text is to offer an approach that will enable students to go

10

KE Y CO N CE PTS IN FEMI NI ST THEORY AND RESEARCH

beyond sin1ply learni ng to live with the n1ulriple conceprualizarions of key tern1s. Ir is to suggest that s uch n1ultiplicity offers an opporrun_iry for rhe developmept of conceptual literacy rhrough which awareness and sensitiviry are developed ro rhe politica l implications of the diversity of conceptual meanings. T hus I am concerned to indicate rhat one of rhe dangers of viewing contests over meaning and rhe politics of language games is that it can suggest an anything goes, relativisr and even cynical approach to debate. Conceptual li teracy is a recognition rhat debate and contescarion impact on the development of a field of study, on rhe production of different forms of knowledge and on changing the language of theory and research . Each of these, in turn, in1pacts on w hat is viewed as the necessary politics of that field. Thus the consequences of debare are real in very material and tangible ways. And so all that remains for me to now say is that I hope some of the 111aterial in chis text is useful to you. 1 know that I learnt a lot in researching it! Christina Hughes University of Warwick October 2001

Concep t s : M e aning s, Games and Co nt es t s

1

I am suggesting neither that there are differences of opinion abo ut concepts which possess an uncontestable core, nor chat concepts are linked to incommensurable theories. Rather I see concepts and categories as shaped by political goals and intentions. Contests over the meaning of concepts, it follows, are contests over desired political outc,omes. (Baccbi, 1996: 1)

,I

did not have sexua l relations with that \.V01nan .' When I first hea rd this statement fron1 President Clinton in respect of his relationship with Monica Lewinsky n1y first response was to judge it in terms of its truth or non-truth. While, of course, there are many kinds of sexual activity surely, I thought, he either had or had not. Yet the C linton case is a classic example of what wou ld be defined as conceptua l conrestation. By this I 1n ea n two things. First, that in the everyday the meanings of particular terms are varied. Second, that in certain circumstances different pro tagonists will forcefuJly and protectively deploy their specific definitions in a contest over meaning. Thus C linton drew on what I persona ll y would understa nd as an extremely narrow, even technical, definitio n of sex. Others deployed a wider meaning char might accord with tnore everyday meanings. The truth did not lie in the physical act that was o r was not underta ken. The truth lay in which defini tio n was go:ing to take precedence. Fo r those of us w ho might have s01ne vicarious enjoyment fron1 the contest over 1neaning in the Clinton case, tbe turn to the drier acaden1ic field of texts and theory has perhaps rather less of a hold on our attention. Yet such texts are full of issues of conceptua l contestation that are enacted in much the same way as the Clinton case. H ere the contests over n1ea ni.ng are central to the development of a particular field of theorizatio n and, in consequence, to the politica l implications of that field. Moi ('I 999) offers a useful example in this respect when she discusses the sex/gender distinction tbat provides the basic framework

12

KEY C ONC EPTS IN FEM INIST THEORY A NO RESEARCH

for much feminist theory in rhe English-speaking world. In contrast co the C linton case where discussion of the term sex was related to the physicality of sex acts, within fen,inism the rerm sex is primarily used ro make distinctions about what is meant when we use the term 'woma n' . T hus sex is the term that is used when referring to \vo ma n as a bio logica lly sexed body and gender is rhe term that denotes the socia ll y produced meanings of \VOn1a n. What is useful a bout Moi's analys is is tbat she illustra tes two in1portant features of conceptual contestation. The first point is that we need to rake account of the histo rica l a nd cultural situatedness of n,eaning. As Moi notes, pri or to 1960, feminists used the te rn, sex co include the socia l and cultural n1canings now associated with gender. In the 1 960s English-speaking femini sts introduced the sex/gende r distinction as a strong defence against the biologically detern1inistic n1eanings that w ere predominant in understa ndings of the term woma n in mascul ine theorizing. In addition, there is no sex/gender distinction in Fre nc h (sexe) and Norwegian (kj@nn). The second poi nt co no te is tha t do1ninanc mea nings are a lways open ro challenge. As in rhe case of the origina l ca ll for a distinctio n bet\veen sex a nd gende r, more recent postscructural theorization has challenged the meanings of sex as being confined to a reference to a biologica ll y sexed body. Moi (1999: 4) notes that the purpose of this challe nge is to shift our understa ndings of the sexed body as a n essence a nd ro refocus rhe meanings of sex as incorpo rating concrete, historical and social phe no1nena . In this w ay poststructura Iist theor izing seeks to a void the biologicall y determi nistic n1eani ngs o f the term sex and co develop an account of sex a nd the body as histo rically located . In the C linton case rhe de bate e ns ued over the n1eanings of sex: bur there never appeared to be a ny doubt about w har constituted woman. Monica Lewi ns ky's sexed body \>vas sufficient evidence. Indeed, in the everyday we rarely spend tin1e analysing and discussing the 111eaning of rhe most comm o n tenns in ou r language. Howeve r, che feminist debates rhat Moi ser8 our in cern1s of the sex/gende r distinction were concerned v.rith rhe meani ngs chat constitute woman. Indeed, ir is rhe theme of 'What is "won1an 11 ?' t hat provides the illustrative fran1ework for chis c hapter as I Jraw on the va ried debates a nd issues th,1r have been of concern in a nswering this q uestio n. This serve a t he context for my primary purpose, which is to set out the rheoriza tio ns of language, meani ng a nd a,crc; of conceptualizatio n rha t have appeared to me to be mosr re levant ro the developn1e nt of m y own imminent understanding of the conceptua l lite r.1cy that I ourlined in rhe Introduction . I rht:refore draw on the theme of ' What is "woman"?' for exem plifica t ion.

CO NCEPTS: MEAN IN GS. GAMES AND CONTESTS

13

I begin with posrsrructuralist understandings of language and meaning. These draw on Derridean notions of the deferral of meaning through differance. There are several points that I have found in1portanr here. The fust is the recognition that is given to the role of language in shaping our understandings of reality. The second is the attention that has been given to the instability of meaning. This has given a focus, for example, co the lack of guarantee over the transference of n1eaning. A rhird point is the attention that is given co the power relations of language. In the section that follows I explore issues of power and language through Plumwood's (1993) deconstruction of dualism . Plumwood's work is exceptionally useful in highlighting the embedded nature of power relations within language. This is because she illustrates how we need to look beyond the coupling or pairing of terms in language. For example, language operates in terms of binaried pairs through which each term in the binary d raws its meaning. H owever, Plumwood's analysis illustrates something of a rhizomatic quality as she also explores how meaning draws from networks and webs of connection that extend beyond the binaried pair. The third section of this chapter is illustrative of how my own conceptual literacy draws from what I now "Understand to be Wittgenstein's philosophy of language. There is considerable debate in the literature on Wittgenstein in tern1s of whether he is a deconstructionist or a pragmatist (see, for example, Nag! and Mouffe, 2001 ). For example, Moi (1999) suggests that the central point where Wittgenstein and Derrida partt con1pany is on the Derridean idea that n1eaning is always deferred. Such debate is, of course, evidence of the rnultiple ways in which we rnight read a particular author. My own concerns with Wittgenstein are rather more mundane. My beginnings here arose from a concern to recognize the contextual dependency of meaning and to find an analytic framework that offered a useful explanation. Meaning n1ay be multiple, varied and diverse. le rnay carry on beyond our intentions and it may be taken up in a host of ways. H owever, meaning is not idiosyncratic in the sense char any meaning goes at any time. If ic were, it would be virtually impossible for us to co1nmunicate. These issues are not denied in poststructuralist theorizing. Meaning is derived from rhe discourse wi thi.n which it takes place (Weedon, 1997). Yer my (mis)reading of work in this field has left me with a strong impression that within standard accounts of poststructuralisn1 the contextualization of meaning is usually in the background of a more fully foregrounded concern to emphasize the transience of rneaning. In my brief acquaintance with Wittgenstein I do not believe thar

14

KEY CO NCE PTS IN FEM INIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

his analysis encourages such backgrounding. Rather, for Wittgenstein, context is key. ln the fourt h section of this chapter l explore the political terrain of contestation of meaning. He re I set our Connolly's ( 1993) analysis of essentiall y contested concepts and his associated term of cluster concepts. lt seems to me tha t Connolly's ana lysis bears a strong resen1bla nce to Wittgenstein's and Plumwood's rhizomacic approaches with their attention to networks and diverse forms of mea ning that branch out in a ll di rections. r also draw on Tanesin i's ( 1994) a na lysis of the policies o f n1ea11.1ing where she highlights cha t we need co understa nd contestation over cneaning as c laims about how a word ought to be used rathe r than as attempts co describe ho w a word is used.

The N on- Fixity o f M ean ing

T he plurali.ry of language and the impossibility o f fixing meaning o nce and for a ll are basic principles of poststructuralism. (\Veedon, L997: 82)

As a ' post'-cheorizacion, poststrucrura lisrn follows o n from che work of structura list theories of lang uage . This is an importa nt point because it draws artention to what is both con1n1on and distinctive co structu ra lism and poststructuralism. ln pa rticul a r, it is de Saussure's srruccura list linguistics char is viewed as being a significa nt forerunner to postscructuralist approaches. Beasley ( 1999 : 90) notes that fo r de Saussure ' meaning is form ulated within la nguage a nd is not somehow to be found o utside rhe ways in which discourse o pe rates'. La nguage is, therefore, nor simply an expression of a preconceived meaning bur instead language creates n1eaning. This point is not at issue for poscstructuralisr theorises. Post t ructuralis1n places considerable emphasis on che role of la nguage in shaping how we know. In addition, de Saussure argued that language has an underlying structure. This underlying structure is co1npr ised of oppositions through which meaning derives. 1 indicated in the Introduction chat the meaning of naivete are drawn froin what \.Ve \,vou ld also understand as not being na"ive. In chis c.;i~e naivete' mea nings a rise rhrough ideas of \.visdom a nd experience. In this way we can conceive of meani ng as derived £com a 'web of ocher concept from \AJhich 1t 1s differentia ted' (ibid.). Again,

CONCEPTS : ME ANINGS. GA MES AND CO NTESTS

15

poststructuralisn1 gives considerable attention to the srructuring of meaning thro ugh oppositiona l and dualistic relations. There are two poi nts of di vergence, however, between de Saussure's structural linguistics and poststrucruralist accounts of n1eaning. One of rhese is that wher,eas de Saussure stressed the fixity of a central underlying structure to language, poststructuralism stresses quite the opposite. Tha t is that n1eaning is fragn1ented and shifting. Indeed, as Weedon (1997) notes, the impossibility of fixin g meaning is centra l to poststructuralist theorizing. AJvesson and Sko1d berg con1n1ent that a n1ajor implication of n1oving away fron1 a belief in a central structure of language is tha t language becomes an open play of never-ending mea ning within tin1e relations. Thus, poststructuralism: ' breaks with the conception of a dlominating centre which would govern the structure, and with the conception that the synchronic, timeless, would be more in1portant than the diachronic, narrative, that which goes on in time'

(2000: 148). Finlayson (1999) illustrates how the approach to meaning as multiple and ten1pora l draws on the notion of hiera rchical binary oppositio ns. The m ost classic exa mple of this is that of the binary n1ale-fe111ale. It is this relational nature of 1neani ng that is seen to give rise to its instability. This is important because it draws attention to how meanings are derived . ln the ma le- fema le binary, to be a won1an requires us ro have a corresponding concept of n1an. Without this relation the terins alone would have no reference point fron1 which to derive their meaning. Nonetheless, it is the relation between these binaries that gives rise to the instability of ,neaning production and reproduction. In particular 'the first term in a binary opposition can never be cosnpletely stable or secure, since it is dependent on that which is excluded' (Finlayson, 1999: 64 ). As understandings of n1ale change, so do those of fe,na le and vice versa. Although meanings canno t be fixed, we Uve our lives as though they are. The appea rance of fixity is n1aintained through ' the s uppression of its opposite' (ibid.: 63). In everyday discourse the fact chat what it means to be masculine relies on what it means to be fen1inine is hidden from view. We are not conscious, for exa111ple, t hat every tin1e we use the word ' wornan', we are using che reference point of n1an to derive our meanings. As Davies (1997a: 9) notes, 'This construction operates in a variety of intersecting ways, 1uosr of which are neither conscious nor intended. They are n1ore like an effect of what we 1night call "speakingas-usual'' .' The notion of am array of deferred meanings is often summarized i_n terms of Derrida's conceptualization of differance. Differance i_s derived

16

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEM INIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

fro m the French verb 'differer', which means co defer or ro puc off. Jo hnson (2000) noces that while the closest English translation is that of ' defern1ent', this loses the complexity o f associations that arise in rhe French. These- are particularly those of rem pora liry, moven1ent and process chat institute difference ' while at the sa,ne time holding it in reserve, deferring its presentation or opera rion ' ( ibid.: 41 ). T hus: Each lmguisric signifier comes laced with deferrals to, and difference from, an absent 'other' - the nega ted binary - that is also in pla>'· Differance Derrida's term for these deferrals and differance - is not a name for a thing, but rathe r 'the mo vement according to whic h la nguage, o r a ny code, any system of referral in general, is consriruted " historically" as a weave of differences'. Thus, the terms ' move me nt', ' is constituted' a nd 'historical ly' need to be unde rs tood as 'beyond rhe metaphysical language in which they a re retained' (1968, p. 65). (Ba tte rs by, 1998: 9 1-100)

Weedon (1997) comments that the issue of differance does not imply that meaning disappears complecely . Differance does focus our a ttention on the temporal implications of meaning and how meaning is open co challenge. H owever ' the degree to which n1eanings are vulnerable at a particular moment will depend on the discursive power relations within which they are located' (Weedon, 1997: 82) . Thus, a second point of divergence between de Saussure's linguistics and poststructuralism is the attention that is given to the relations of power within language. One way of illustra ting rhis is through the attention that has been given to rhe analysis of dualism and the processes of deconsrrucrion.

Dual ism

A dualism is more than a relation of dichotomy, difference, o r nonidentity, a nd more than a simple hierarchical relationship. fn dualistic construction, as 111 hierarch y, the qua lities (actual o r ~upposed), the c ulture, the values and the areas of lifr associated with the dualised other are systematically and pervasively constructe d a nd depicted as LUfcrior. Hierarchies, however, can be seen as open to change, as co11ringenr a nd shifting. But once the process of domination forms cu lture and constructs identity, the infcriorised group (unless it can marshall cultura l resources for resi~tancd must internalise rhil> inferiori~:Hion in it5 identity a nd collude 111 rh1s low valuatio n, honouring the value~ of the centre, wh11..h forn1 the dominant socia l values .. . A dua li~m is an inrense, C\tabfo,hcd and developed cultural expression of such a hierarchical

CONCEPTS: MEA NINGS. GAMES AND CONTESTS

17

relationship, constructing central cultural concepts and identities so as to make equality and mutuality literally unthinkable. (Plumwood, 1993: 47)

Plumwood illustrates an important feature of the organization of language and its relations to power. This is that of the e1nbedded nature of hierarchization that goes beyond a sin,ple binary. The key elements of dualistic structuring in Western thought include culture/nature, reason/ nature, male/female, mind/body, reason/emotion, reason/matter, public/ private, subject/object and self/other (ibid.: 43) . These, however, are not discrete pairs that bear no relation to other concepts in language. Rather, dualisms should be seen as a network of strongly linked and continuous webs of meanings. For example, ' the concepts of hwnanity, rationality and masculinity form strongly linked and contiguous parts of this web, a set of closely related concepts which provide for each other models of appropriate relations to their respective dualised contrasts of nature, the physical or material, and the feminine' ( ibid.: 46) . In this respect, as Hekman (1999: 85) notes, rationality, humanity and masculinity fonn 'the ideal type that forms the central core of modern social and political theory'. Plumwood secs out five features that she argues are characteristic of dua lism. These are: •

•

Backgrounding (denial) Plwnwood comments that the relations of domination give rise to certain conflicts as those who do1ninate seek to deny their dependency and reliance on those they dominate. Denial of this dependency takes n1any forms. These include 1naking the depended upon inessential and denying the importance of the other's contribution. The view of those who dominate is set up as universal 'and it is part of the mechanism of backgrounding that it never occurs to him that there might be other perspectives from which he is background' (1993: 48). Radical exclusion (hyperseparation) Plumwood argues that radica l exclusion is a key indicator of dualism. Radical exclusion or hyperseparation arises because those who are superior need to ensure that their distinctiveness is perceived to be more than mere difference. For example, there may be a single characteristic that is possessed by one group but not the other. This 'is important in eliminating identification and sy1npathy between members of the don1jnating class and the don1inated, and in eliminating possible confusion between powerful and powerless. It also belps to estab.lish

18

•

•

•

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMINIST THEOR Y AND RESEARC H

separate "narures" which explain a nd jusrify widely differing privileges and fares' (ibid.: 49). Incorporation (re lationa l definition) Incorporation or relational definitio n ·occur where masculine qua lities, for example, a re taken a pri1nary. 'X' hile the meanings of fem injnity a nd mascu linity rely o n each other, rhis is nor a relationship of equals. Rather, 'rhe unde rside of a dualistically conceived pair is defined in relation to rhe upperside as a lack, a negativity' (ibid.: 52). fnstru1nentalism (objectification) fn strumentalisrn or objectification is rhe process whereby those on rhe lower or inferior side of the duaury have to pur their interests asi de in favo1.1r of the dominant and indeed are seen as ' his instruments, a n1eans to his e nds. They are n1ade part of a network of purposes w hi.c h are defined in terms of or harnessed to the master's purposes a nd needs. The lower side is also objectified, without ends of its own whic h demand consideration on their own accoun t. Its ends are defined in tern1s of rhe m aster's ends' (i bid.: 53). Homogenization or stereotyping H omogenization or stereotyping are ways through w hich hierarchies are main tained beca u e they disregard an y d iffe rences amongst the inferiorized c lass. Such a view would suggest, for example, that all women are the same.

Plurnwood 's a pproach ro this a nalysis of dualisn1 would be described as deconsrructive. Deconscrucrion has been a significant cool in the pourics of femin ism ch at has facilitated an understanding of how truths a re produced (Spivak, 2001). In this, deconstruction is nor simply concerned with overrurnjng binaried thinking but in illustrating how renns draw on their mearung fro111 their d ualistic positioning.

Deconstruction

Building on the notion of differance, deconstruction sees social life as a series of texts that can 1::-e read in a variety of ways. Because of this multiplicity of readings there is, therefore, ;.1 range of meanings that can be invoked. !vloreover. through each reading we are producing another cexr co the extent that we can view the socia l world as the emanations of a whole array of inrertextua.l weavings. While there is this variecy, as we have seen, texts conca1n hierarchical concepts organized as binaries. Deconstruction does nor c;eek ro overturn the bin ary through a reversal

CONCEPTS: MEAN ING S, GAMES AND CONTESTS

19

of dominance. Thi, ,-vou ld simply maintain hierarchization. Deconstruction is concerned to illustrate how language is used co fran1e 1neaning. Polirically its purpose is co lead co ' an appreciation of hierarchy as illusion sustained by power. It may be a necessary illusion, at our stage in history. We do not know. But there is no rational warrant for as un1ing char other irnaginary structures would not be possible' (Boyne, 1990: 124). To achieve this deconstruction involves three phases (Grosz, 1990a). The first two of t hese are rhe reversal and displncen1ent of the hierarchy. In terms of reversal we ought, for exan1ple, seek to reclaim the terms Queer or Black for n1ore positive interpretations of their mea ning. However, ir is insufficient simply to cry to reverse rhe hierarchical status of any binary. At best, this simply keeps hierarchical organization in place. Ar worst, such attempts will be ignored because the dominant meanings of a hierarchical pairi ng are so strongly in place. This is wby it is necessary to displace con-1mon hierarchized meanings. This is achieved by displacing the 'negarive term, moving it from its oppositional role into the very heart of t he dominant term ' (ibid.: 97). The purpose of this is to make clear bow the subordinated term is subordinated. T his requires a third phase. T his is the creation of a new rerm. Grosz notes char Derrida called the new term a 'h inge' word . She offers the following examples: such as ' trace' (simultaneously present and absent), 'supplement' (simultaneously plenitude and excess); 'diffcrance' (sa meness and difference); 'pharmakon ' (simultaneou ly poison and cure); 'hymen' (simulraneously virgin and bride, rupture and roraliry), etc ... These 'hinge words' ( in Iriga ray, the two lips, nuidity, materna l desire, a genealogy of women, in Kriste va, semanalysis, the semiotic, polyphony, ere.) function as undecidable, vacillating between two oppositional terms, occupying the ground of their 'excluded middle' . If strategica lly harnessed, these terms rupture the systems &om which they 'originate' and in which they function. (ibid.)

Grosz comments char chis is borh an impossible and necessa ry project. le is i1npossible because we have to use the terms of any dominant discourse to challenge that discourse. It is necessary because such a process illusrraces how so much of what is said is bound up with what can not be, and is not, said. In this respect, Plumwood's analysis iJlusrrares the systematization of power relations tJ1ac operate through networks of conceptual dualisms. She refers to the five features she bas identified as a family and thereby indicates that they each have complex kinships with each other. F in layson (1999) denotes rhe attention given co issues of power relations

20

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMINIST T HE ORY AND RESEARCH

wirhin poststructura list ana lyses of language in tern1s of the turn to discourse. Accordi ngly, Finlayson defines discourse as referring both 'to the way lang_uage systematica lly organjzes concepts, knowledge and experience and to the way in which ir excludes alternative forn1s of organization. Thus, the bow1daries berween language, socia l action , know ledge and power are blurred' (ibid.: 62). Foucault (1972: 25) a lso illustrates how the meanings of discourse rely on what is left in the background. H e comments that a ll manifest discourse is secretly ba ed on an 'a lready-sa id'; a nd ... this ·already-said' is nor merely a phrase that has already been spoken, or a text that has: already been written, but a 'never-said', an incorporeal discourse, a voice as silent as a breath, a wriring that is merely the hollow of its own mark.

Gee (1996) comments on how dominant discourses are intin1ately related to the distribution of social po,.ver and hierarchical structure in society. Thus, control over certain discourses can lead ro the acquisition of social goods such as money, power and status in a society. The significance of this focus o n discourse is that it directs our attention to the constellations of language. Language is nor free-sta nding a nd nor are dualistic fra1neworks but part of what Wittgenstein defined as language games.

language Games

Of course lang uage in general and concepts in particu lar often carry ideological implicacions. Bur as Wittgenstein purs it, in mosr cases rhe meaning of a word is its use. Used 111 differenr siruacions by different speakers, rhe word 'woman· takes on very differenr implica tions. If wc want to combat sexism and hererosex1sm, we sho uld ex.'lmine what work words are made to dlJ in different speecl1 acts, not leap to the conclusion that the same word must mean the same oppressive thing every time 1r occurs, or that words oprress us ,imply by having derermmate meaning~. regardless uf what cho~e mcanrngs arc. (Moi, 1999: 45)

Moi is concerncJ to 111dicate char argun,ents char suggest that every usage of the term 'woman' is exclusionary are misplaced. H e re she

C ON CE PTS: MEA NIN GS, GAM ES AND CONTESTS

21

draws on Wittgenstein's (1958, s 43) dictum chat ' For a large class of cases - rhough not for all - in which we en1ploy the word "meaning" ir can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.' Thus, Moi com n,ents, 'In my view, all the cases in which feminists discuss rhe meani.ng of the words woman, sex and gender belong to the "large class of cases" Wittgenstein has in n1-ind' (1999: 7) . Her argument is that Wittgenstein proposes some convincing philosophical alternatives ro certai n posr-Saussurean views of language. Wittgenstein \.Vas concerned that any analysis of language shoul d not be abstracted from the context of its usage. In this Wittgenstein was concerned that 'philosophy should not provide a theory of meaning at all: one shou ld look at how words are actually used and explained, rather than construct elaborate fiction s about how they must work' (Stern, 1995: 41). Jn this respect Wittgenstein's later concerns opposed his earlier work in the Tractatus char argued that language had a uniforn1 logical structure that can be disclosed through phi losophical analysis. Rather, in his Philosophical Investigations he thought that 'Language bas no conm1on essence, or at least, if it has one, it is a minimal one . .. connected ... in a more elusive way, like games, or like the faces of people belonging to the san1e fan1i ly' (Pea rs, 1971: 14). For example, although a word may have a uniform appearance this does nor mean that its meaning will be si.n1ilarly uniform and from which we can make generalizations. Wittgenstein illustrated this point through an analysis of the word 'games'. When we use the word 'gaines' we 1niglht refer to board gan1es, card gan1es, ball games, Olyn1pic ga1nes, an d so forth. He comments that instead of sayi ng because they are all games there n1ust be something common to chem we should 'look and see whether there is anything common to all ... To repeat: don't chink, but look!' (Wittgenstein, 1958: s 66) . For example, some b.all games, such .as tennis, involve winning and losing whereas some ball games, such as when a child throws a ball against a wall, do not. If we extend the analysis to ga1nes that do nor use a ball we wiJI find that again some are about winners and losers and others are not. For exa1nple1 games such as ring-a-ring-a-roses are amusing bur not competitive. Chess games are competitive. Overall 'the result of rhis examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail' (ibid.). Wittgenstein ca lled these relationships 'fan1ily resemblances' and argued that 'the Line between \\,hat we are and are not prepared to call a gan1e is likely (a ) co be fuzzy and (b) to depen d on our purposes in seeking such a definition' (Winch and Gingell, 1999: 58).

22 KEY CONCEPTS IN FEM INIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

McGino (1997: 43 ) co1nments that the conceptua lization of la nguage ga1nes brings ' into pron1inence the fact that language fu nct ions within t he active, pr~ctical lives of speakers, that its use is inexrrica bly bound up with the non-linguistic behaviour which constfrutes its natural environmen t'. T hus an analysis of meaning has to be considered in rela tion to its usage rather than as an abstraction fron1 its context. In this way Wittgenstein asks us to chjnk t hrough the taken-for-gra nted of everyday speech a nd co begin co not ice cha t which we never notice . T his includes both linguistic and non-linguistic features. As M cGinn con1n1ents: Wittgenstein's concept of a language-game is clearly to be set over and against the idea of language as a system of meaningful signs that can be considered in abst ractio n from its actual employment. Instead of approaching language as a system of signs w ith meaning, we are prompted to think a bout it in situ, embedded in the Jives of those who speak it. The tendency to isolate language, or abstract ir from tbe context in which it ordinarily Jj ves, is connected wirh our adopting a theoretical attitude towards it, and with our urge to explain how these mere signs (mere marks) can acqui re their extraordinary power to mean or represent something. (1997: 44)

Thus Wittgenst ein argued that we s hould look at the spatial and temporal phenornen a of language rather than assu1ning 'a pure intern1ediary between che propositional signs and the facts' (McGinn, 1997: 94) . In this way we would see that ' our forms of expression prevent us in all sorts of ways from seeing that nothing out of the ordinary is involved' (ibid.) and that 'everything lies open co view there is nothing to explain' (Wittgenstein, 1958: s 126). I n taking up these perspectives from Wittgenstein iv1oi applies this co rhe tendency within son1e postscructuralist writings to a void a ny reference to biological facts because it 1,vould imply some form of essentialis1n. In order co avoid biologica l detern1inisn1 some fe1niniscs 'go ro t he other extren1e, placing biological facts under a kind of mental e ras ure' (Moi, 1999: 42). The theoretical reasons given for chis are that 'political exclusion is coded into the very concepts we use to n1ake sense of the world' ( ibid.: 43, en1phasis in o riginal). Thus it is argued char the word 'won1an · is al1,vays ideological and '''vvoman" 1nust mean "heterosexual, feminine and fen1ale"' ( ibid., emphasis in original). When such terms such as ·woman' are used, posrsrructura lists take recourse in the slippery nature of mean ing in order ro construct an a rmoury of defence against accusa tions of cssenrialism . As M oi con1ments, this is to soften any in,plicacion of exclusion bur such ::1 position is n1isplaced and

CONCEP TS: MEANI NGS , GA MES AND CO NTESTS 23

is based on the incorrect vie,v that the tern1 'woman ' actually does have only one meaning and that meaning is independent from the context of its use. If this were rhe case, we would be una ble to envisage any alternative kind of meaning for 'woman'. Th us, Moi comn1ents: The incessant poststructuralist invocations of the slippage, instability, and non-fixity of meaning are clearl y intended as a way to soften the exclusionary blov, of concepts, but unfortunately even concepts such as 'slippage' and ' instability' have fairly stable meanings in most contexts. It follows from the poststructuralisrs' own logic thar if we were all mired in exclusionary poJj cics just by having concepts, we would not be able to perceive the world in terms other than the ones laid out by our contaminated concepts. If oppressive social norms are embedded in our concepts, just because they are concepts, we would all be stri ving to preserve existing social nonns. ( ibid.: 44)

M oi is clear that her appeal that we should focus on the ordinary, everyday usage o.£ terms is not to argue all 1neaning is neutral and devoid of power rela tions. Rather, she is indicating that any analysis of meaning has to cake account of che speech acts within which it is placed. In different locations and used by different speakers the term ' woman' has a range of different meanings. One has to understand such location and to understand the world from the perspective of the speaker. Or as Luke (1996: 1) reminds us 'concepts and meanings ... are products of historically and culturally situated social forn1ations'. In addition, in caking up Wittgenstein, Moi is not arguing for a defence of the sta tus quo, the conunonsensical or the do.m inant ideology. Rather, she is directing our attention to the everyd ay as a place of struggle over meaning. In this she con1ments, 'The very fact that there is continuous struggle over n1eaning (think of words such as queer, wo1nan, democracy, equality, freedom) shows that different uses not only exist but sometimes give rise to violently conflicting 1neanings. If the meaning of a word is its use, such conflicts are part of the meaning of the word' (1999: 210). It is co the political struggle over meaning that J now turn.

Contests about Meaning

A common strategy in the management of concepts in social research is co take a technical approach. This requires the operationalization of a

24

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMIN IST TH EORY AND RESEARCH

concepr into key indicators. A classic sraremenr in chis regard would be 'Concepts a re, by rheir nature, nor directly observable. We cannot see social class, .marital happiness, inrelligence, etc. To use concepts in research we n eed to translate concepcs into something observable so1nething we can measure. Th is involves defining a nd clarifyi ng abstracr concepts a nd developing indicators of them' (de Vaus, 2001: 24). 1r would be a mista ke to believe that such concerns are prima ril y related to chose w ho undertake forms of research that rely on hypothesis resting and q uantification. Quali tative researchers who work with rheory building and analysis fron1 n1ore 'grounded' approaches similarly recognize that the ma nagen1ent and ana lysis of data require conceptual clarification. For example, Miles and Hube nnan (1994: 18) no te chat 'general constructs ... subsume a mountain of particulars' . Miles and H uberman label these constructs 'intellectual "bins" containing many discrete events and behaviours' ( ibid.). An intellectual 'bin' might, therefore, be labelled role conflict or cu ltural scene. In the operationalization of concepts de Vaus (2001: 24) nores that one needs to descend 'the ladder of a bstraction' and move from nominal definitions, such as, say, class, chat simply convey a broad category and conclude ou r descent with operational definitions. For example, rhe operational definition of class n1ay he occupation, salary and/or it 111ay be the self-definition of the researched. These operational definitions, or indicato rs, would then forn1 part of a questionnaire, interview or observation. Miles and Hu berman suggest chat however inductive in approach, any researcher 'knows which bins are likely to be in play in the study and what is likely to be in t he m. Bins coines fron1 theory and experience and (often) from rhe general objectives of the srudy envisioned' ( L994: 18). The researcher therefore needs ro name the relevant ·bins', describe their con tents and variables and consider their interrelarionsh1p vvith othe r 'bins' in order to build a conceptual framework. As de Vaus make,; clear, the importance of descending the ladder of abstraction is ro ensure the validity of research. Validity here is concerned with ·whether your methods, approaches and technique actua ll y rel:.ire ro, or measure, the issues you have been exploring' (Blaxcer et al., 2()0 l: 221 ). Jn rhic; an adequate operationalization of a concept through rhe use nf indicaror~ enables researchers to sustain the clai,ns chat a re made for n:~earch in te rms of causality, warrantahiliry or tru rworthine% . In qual1rat1ve resea rch working wirhin dec;igns rhar require precision in na ming and labell1ng conceptual 'bins' facilitates cross-case comparL1bdit) and can enhance its conlirn1ntory aspects (Miles nnd Huberman, l ':il94).

C ON CEPTS: MEAN INGS. GAMES AN D CO NTES TS 25

There is no doubt that issues of reliability , validity, "varrantability and comparability are exceptionally important in the design and conduct of research. The processes that are required through which researchers delineate concepts into indicators or categorize conceptual 'bins' facilitate an important recognition of the complexity of the social world and this ia rurn facilitates clarity and focus. H owever, many textbooks that discuss the issue of concept-indicator linkages imply that this is primarily an issue of technical difficulty. This is because, as any initial introduction to social research will indicate, there are a host of indicators chat could be applied to any concept. For exa1nple, in the field of social gerontology the collection in Peace (1990) indicates how concepts such as age, dependency and quality of life have varied indicators. H ere Hughes (1990: 50) notes that the definitiona l problems that arise when conceptualizing 'quality of life' arise ' in part fron1 the problem of integrating objecti ve and subjective elements and indeed, of determining which elements ought to be included' . These wou ld include occupation, material status, physica l health, functional abilities, social contacts, activities of daily living, recreation, interests, and so forth. Hughes also notes that the con1plexicy of these indicators is further compounded by the variables of ' race', gender and class. Hughes co1nments that there is, inevitably, disagreement about the 'correct' indicators that would designate quality of life. This appears to be pa rticularly che case in terms of the importance given to subjective data. For example, how does one weight the feelings and views of research respondents about the quality of their life in compa rison to what a re seen to be more objective data such as income, housing conditions, and so forth? However, Hughes argues that one should not abandon the search for an integrated conceptua lization that would combine subjective and objective data as this 'would be to deny gerontological research vital evidence' ( ibid.: 51 ). Such a statement implies that if all researchers in a fie ld of enquiry cou ld agree on a set of required co1nponents, indicators or variables the problem of validity "vould be solved. J-Iowever, it is a 111istake to assun1e that what are often portrayed as technical issues are devoid of the political and that the delineation of a concept into a set of indicators is primarily a neutral act. lt would be a mistake also, therefore, to assun1e that the issue of va lidity is resolved by recall to son1e set of apolitical technical acts. This assun1es that the function of such indicators is purely descriptive rather rhan that such descriptions ascribe values that license inferences about what is warrantable and pern1issible (Connolly, 1993; Tanesini, 1994). To explore this furthe r f turn here to an analysis of the divergence of opinion that arises in academic, and other, debates about the 'correct' meaning of concepts.

26

KEY CO NCE PTS IN FEM IN IST T HEOR Y AND RESEARCH

Swanton (1985) describes the contestarion over conceptual definitions in tenns chat: • • •

certain concepts admit to a variety of interpretations or uses; the proper use of a concept is disputable; varied conceptualizations are deployed 'both "aggressively and defensively' ' agrunst rival conceptions'. (ibid.: 813)

The question is ' Why do such contestations arise? ' Conno lly (1993) indicates how the internal complexity of certain key concepts gives rise to contestability over n1eaning. Thi s interna l complexity arises because, as Henwood (1996) makes c lear in her analysis of dualism, certain key concepts form a web of connections. Conn o lly refers to these a s cluster concepts. For example if we ask 'What is "woman"?' we might respond that she is relationa l, caring, 'raced', classed , aged, en1bodied, and so forth. We are, the refore, required to consider ' won1an' in respect of decisi o ns about a further broad range of contestable tern1s. This is because the interpretation of a ny of these rern1s is relatively open. For example in deciding what ' woman' is we also have to decide what 'race', c lass, age and e mbodin1ent are. Thus what are our indicators if we rake ' race' as o ur variable? There are certainly a whole a rray of te rn1s: Black British, Women of Colour, Black African American , and so forth. Certainly son1e individuals with South Asian heritage have o bjected ro being encomp assed within the tern, ' Blac k' as they do nor identify with such a conceptualizatio n of their ethnicity. M ore recently issues of Whiteness have come to the fo re as central ro any conceptualization of 'race'. As a result it has been a rgued that ignoring issues of Whiteness does no t do justice co a proper conceptua liza tio n of ' race'. Thus, as Connoll y a rg ues, a tern1's 'very characteristics as a cl uster concept provide the space within "vhich such contests [of n1eani ng] emerge' (1993: 15). Connolly a lso raises a further issue in this respect. 1-le uggesrs char if the issue at stake is 111erely a questio n o f technica lities, then it is within the rea lms of possibility that researche rs could agree on a sec of finite inJicacors and whenever they use a particul ar concept these ,votild be used. Yet this doe not happen . Indeed, he indicates t ha t contests over meaning are nor perceived simpl y a irksome ::i nd a problem arising from the technica lities of naming and defin ing. Rather, contests over meaning an: !.e-en ro be highly im porta nt in academic debate. Wha t, for example, doe? It i~ ~elf-cvidenrially true rhat this I a con1mon descriptor of

CO NCEPTS: MEANI NG S, GAMES AND CON T ESTS

27

many women. The reply is that ic to ignore Whiteness is co imply that ' race' issues are not che concern of White people when pa lpably they are. In exploring che extent of debate over new forn1s of conceptualization Connolly suggests chat two issues are at scake. The first is related co claims ro validity. As we have seen, rhe use of indicators co give conceptual clarity is linked directly to the internal and external vaJidiry of a research study. Thus conrestabiliry arises because of the connection between the use of 'correct' indicators and what can be claimed for the findings of any research. If one has not used the appropriate indicators then, of course, one's research is invalid. The second issue relates to the theoretical frameworks within which a research study is placed. Connolly notes that researchers often have intense attachment co particular theoretical fields as offering the most sali ent of explanations for pa rticu lar phenomena. Contestation over meaning therefore also impacts on the truth claims for a ny theorization. As Connolly notes: The decision to make some elements 'part of' clusrer concepts whi le excluding others invokes a complex set of judgements about the validity of claims central to the theory within which the concept moves .. . the multiple criteria of cluster concepts reflect the theory in which they are embedded, and a change in the criteria of a ny of these concepts is likely to involve a change in the theory itself. Conceptual disputes, then, are neither a mere prelude to inquiry nor peripheral co it, but when they involve the central concepts of a field of inquiry, they are surface 1nanifestations of basic theoretical differences that reach to the core. The intensity of comm itment to favored defi n itions reflects intensity of commitment to a general theoretical perspective; and revisions that follow conceptual debates involve a shift in the theory that has housed the concepts. (1993: 21 )

These issues can be further illustrated through an exploration of the common distinction that is made between nonnative and descriptive meanings of a concept. For exan1ple, in the case of 'What is "won1an"?' identity and postcolonial fen1ini sts have indicated that the normative n1ea nings of won11an in early second-wave femi11isn1 are those of White, Western and n1iddle class. To use the word ' woman' therefore implies that you are invoking tbis meaning. 1-:Iowever, the distinction between norn1arive and descriptive claims for a concept is often confused (Connolly, 1993; Tanesini, 1994). In particular those who invoke descriptive claims as if they were either sin1ple issues of fa ct or technicality ignore 'a fundan1encal feature of description: A description does not refer to data or elements char are bound together merely on the

28

KEY CONCEPTS IN FE MIN IST T HEORY AND RESEARCH

basis of sin1ilarities adhering in then1, but to describe is t o characterize a situation from the vantage point of certain interests, purposes, or standards' (Connolly, 1993: 22-3, emphasis in original). When claims are n1ade rhat"che 'woman' of early second-wave feminism is Western or White or n1iddle class, the central issue is not one of e1npirical fact. The issue is one of values. To assert rhe empirical facts of the diversity of 'woman' is to make clain1s about the values that we attach to that concept. White, Western and middle class are not descriptors but are in themselves concepts imbued with a host of value-led meanings. Thus: Essenrially conresced concepts ... are typically appraisive in that to call something a 'work of art' or a 'democracy' is both to describe it and to ascribe a valrue to i.t or express a commitment with respect co it. The connection within che concept itself of d escriptive and norma rive dime nsions helps to explain why such concepts are subject to intense and endless debare. ( ibid.)

In this light we can see that contests over meaning are not technical issues. Rather, they arise because conceptualization has an inferentialjustificatory role. To claim that a particular n1eaning of a concept is the only valid one is to license t he future use of that particular meaning. This means that contests over meaning are accounts of how terms should be used which, if successful, impact upon practices and theorization. Tanesini comments here that: Meaning-claims rhen do nor perform any explanato ry ro le; the ir purpose in language is rhar of prescribing emendations or preservations of c urrent prac tices. In pa rticular, rheir funcri()n is not cha t of descri bing the inferential-jus tificatory role of any linguistic expression. Tha t is, the y do not explain rhe content o f an expression . Instead, meaning-cla ims are pro posals a bo ut emendation or preservation of the roles of expressions; these cla ims become prescriptive, if one is entitled to ma ke them. As pro posals for iJ10uencing the evolution of ongoing practices, meaningclaims are grounded in socia l practices. ( 1994: 207-8)

As ,vc have seen in the case of '\'Qhat is "\,voma n" ?' feminists who do not wa11t to be seen as either racist, clas!>iSt, colonia list or essentialist may ar minimum qualify the term by adding what Butler ( 1990) refer to as rhe 'cn1 ba rrassed etcete ras' of 'race', cla, s, etc. etc. This has certa inl y fu nctioned ro add ro rhc list of de criptors what we n1ighr mean hy 'wo 111 an' . Howeve r, Tancs1ni also notes that more rece ntly the concern over 'Whar 1s " woman"?' ha raken a new ep1sren1ologica l turn . The lisr of descriptors has encour.1ged a sense o f fragmenra non of the concepc

CONCEPTS: MEAN INGS, GAMES AND CONTES TS

29

of woman so that it is now no longer a useful category. Tanesini comn1ents: Gender sceptics claim that racist, becerosexisr and classist biases are part of the logic of the concept of gender. In other words, they claim tbat it is conceptually impossible to use the notion of gender without engaging in exclusionary practices. They hold that, if one is attentive to differences of ethnic origin, sexual orientation and class, the notion of gender disintegrates into fragments and cannot be employed any .m ore as a useful category. (1994: 205)

In Tanesini's view, we would not understand these arguments simply as part of developing our understandings of the impossibiJity of ever fu!J y describing 'woman' because of the multitude of descriptive elements of which she is com.prised. Rather, we would see these arguments as an intervention in a debate that seeks to justify future use, or indeed nonuse, of a concept. T he in1plication of the argument that the term 'woman' is inevitably normative and exclusionary is that we should cease using the term . We might even invent a new one in terms of a broader deconstructive strategy. H owever, as part of a counter-debate about this essentia lly contested concept we n1ight also intervene and argue that the tenn 'woman' shou ld be retained . [n this case Moi (1999) den1onstra tes how we might draw on an alternative theoretical framework as a way of interceding. In this we might argue chat it is quire permissible to continue using the word 'woman' because our 111eanings should be clear from the context. If feminises take up M oi's position, rhen we might see a change in theoreticaJ framework that, say, more fully incorporates Wictgensteinean theories. If femjnists take up the claims of 'gender sceptics' then we might find new tenns created for 'won1an' or the use of the term ceasing altogether in feminist analysis. What this Jatter position might mean for feminist politics is, of course, a 11100c point.

Case Study 1: 'Progress' in Zimbabwe: Is 'It' a 'W oman'? I have been concerned in this chapter to indicate something of multiple meaning and conceptual contestation. I have used the question 'What is "woman"?' at various points for exemplification. Sylvester (1999) is similarly concerned with the meanings and representations of 'woman' and her research explores this through the further problematic concept of progress. Specifically. Sylvester considers how, and if, we can conceptualize progress through women's lives and testimonies. The framework

30

KEY CONC EPTS IN FEMIN IST THEORY AND RESEARCH

of Sylvester's paper is a deconstructive analysis of narratives of progression and its linkage to issues of identity. In this she notes: 'Progress is at once a very common, common notion, easily grasped by the modern mind, and something difficult to understand and make happen or co repudiate absolutely' (ibid.: 90). As Sylvester also notes, progress can be an embarrassing word for feminists a.s it reminds them of a one-for-all 1970s' marching feminism where progression was guaranteed once one could agree on the best route to utopia. Clinton exemplifies the ambivalence toward progress in contemporary feminist theorizing as 'Sex in the US White House humbles some feminists for whom that skulker in dark corridors has been a darling of progress for women' (ibid.). Thus. 'Progress exists/does not exist, is asserted/contested in many ways. How does one investigate the elusive relevant and irrelevant wanted and absent? How does one research trickster " progress" at this point in time?' (ibid.: 91). Sylvester's response to these questions is to argue that what is vitally necessary is to 'refocus and look at the everyday social constitution of ''progress'" (ibid.: 92). Her paper is therefore based on interviews that she conducted between 1988 and 1993 with women in Zimbabwe's commercial farming and factories. Here she is concerned to 'telescope' their descriptions of their daily work and their desires for what they do not have. This is because 'the usual ways of studying progress (e.g. through statist ical and economic analyses] are not designed to take the concerns of local "women'' into account' (ibid.). The questions that Sylvester asked included whether they found their work met their expectations or was satisfactory, what changes, if any. they would make in their workplaces and what they would do if they were the President of Zimbabwe. Most importantly, Sylvester adds, she asked 'Are you women?' and "How do you know/' Sylvester threads this interview data with fictional representations of women from noted Zimbabwean literature produced in the 1980s and early 1990s. Sylvester's research illustrates the connections between meanings of progress and meanings of 'woman' in varied ways. In fiction these connections include:

• •

•

woman as having progressed because she is 'freed from the fetters of loyalty to fixed and inherited places' (ibid.: 94); wo man as in need of progress because she 1s 'the dregs of agricultural labor ... the non -permanent. casual. ... desperate' (ibid.: 94- 5); wo man as progre ss be cause she is the labour aristocracy.

CONCEPTS : MEAN INGS . GAMES AND CON T ESTS

31

Women's own accounts similarly illustrated these fictionalized elements and illustrated how women experienced sexual harassment and the common gendered inequalities in access to promotion, permanent work. equal pay and positions of power and influence in worker representation systems. Their testimonies also illustrated how women sought to circumvent and resist these imperatives to lack of progress. Sylvester indicates how '"Progress" existed in everyday narratives of effort and movement and in the counter-efforts of others to patch up problems and get on with progress' (ibid.: 111 ). The women that Sylvester interviewed also offered multiple meanings of woman. They noted that they could not speak for 'all' women, that some women may have different views and politics about 'progress'. Sometimes they could point to particular women as exemplars of progress. Nonetheless, 'Always [progress] was a desiring of movement around the usual rules for women at work. And just as always, the outcome would be ambiguous. Would the fiesty factory "women" be promoted? Would commercial farm "women " get women supervisors? Were the transgressions we noted powerful or just quick tricks?' (ibid.: 112). Sylvester's paper makes it clear that there are no easy answers to these questions. This is because in terms of its meanings and empirics, 'Progress is so tricky' (ibid.: 113).

Summary

As an opening chapter 1 have attempted to illustrate what has influenced my own thinking in framing this text. What follows explores key terms in feminise theory to illustrate their diverse conceptualization a nd their applica tion in ferninist research. In the concluding chapter T return to the issue of conceptual literacy. H ere l an, concerned to indicate ways in which conceptua l lite racy might be further developed.

FURTHER READING

Connolly. W . (1993) The Te rms of Political Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell (Third Edition). This is a classic text on conceptual contestation. It is written primarily for politics students and draws on the term ' politics· for exemplification.

32

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEM INIST TH EORY AND RESEARCH

Plumwood, V. (1'993) Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge. Plumwood does an excellent job in illustrating the distinctions between binaries and dualism. I have only had space here to draw attention to this issue and so would recommend much fuller consultation of her work.

Eq u a li ty

2

An understanding of male and female as distinctly different and complementary to an understanding of nia le and feniale as equal was a radica I shift in gender ideology.

(Ivlunro, 1998: 52)

E

vans (1994) suggests that there are three issues that are central to contemporary fenunist conceptualizations of equality. The first is that the most common assumption made about the meaning of equality is that this must n1ean ' the sa me' . Thus feminists have argued that as we are all born equal we should be treated as equa ls. But, of course, this begs rhe question ' Equal to what?' The measure, or the normative standard, of that equality has been men's lives. Men had the vote, property rights and access to education and so these became spheres of early feminist campaigning. More recently, fen1inists have noted how men still maintain their positions at the cop of employ111ent hierarchies. As a result, feminist campaigns for equality have sought to break through the metaphorical glass ceiling that prevents access to higher pos1nons. It is true to say that sorne of the achievements of feminism have been in terms of accessi ng the public realms of social life. There are more women in the British Parlian1ent and more women in managerial positions in organizations. In terms of legislative change, it is almost four decades ago that the Equal Pay Act (1963) was passed in the United States. ln the UK it is just over three decades ago that the Equal Pay Act (1970) was p assed and over a quarter of a century ago that the Sex Discrimination Act (1975) was passed. Despite these changes, parity with n1en in all of these arenas is yet to be achieved. And, internationally, it should be ren1embered that such legislation is not a global phenomenon . .H owever, it is women 's responsibilities in terms of the family that appears to be the most resistant to change and this brings us to the

34

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEM IN IST THEOR Y AND RESEARCH

second issue that Evans highlights as central to feminist conceptualizations of equality. This is thar this has focused prin1arily on achieving equality based_ on entry into paid labour. A key problem with this is rhar ir has left won1en's family responsibilities unchanged. Research has demonstrated how greater access ro paid employn1ent cannot be viewed simply as a liberati11g phenomena chat leaves won1en less dependent on male partners and more fulfilled as individuals. Indeed, it is evident that won1en either have to .m anage as best they can the tvvo greedy spheres of paid work and family and/or take part-tin1e, flexible empl oyn1ent with its associated lower economic and social value. This has led to continuing lobbying for a range of policies uch as childcare facili t ies, maternity and paternity leave, llexible \Vorkiog hours, and so forth. Third, whue equality has not disappeared, it has more recently been under sustained critique. for exan1ple, rhe assumption that equality means 'the san1e' has been explored in tern1s of its political and philosophical irnplications. The notion rhat won1en should view rhe masculine as the normative, that is as rhe goal co be achieved, is certainly nor o ne that is ascribed co by all feminises. For exan1ple, cultural feminises have sought co valorize rhe fe111inine and have argued rhac women are indeed different to rnen. Their political goal is to have an equal value placed on women's difference. Plumwood (1993) suncma rizes these positions wi thin discussions of equality in terms of rwo models. One of these she calls 'the fen1inisn1 of uncritical equality'. This is associated wirh models of femi nism in the 1960s and 1970s rhac 'artempred ro fir women uncritically inro a masculine parrern of life and a masculine n1odel of hun1aniry and culture which was presented as gender-neutral' (Plumwood, 1993: 27). Although chis position is n1ainly associated with liberal feminism, it should be nored rhat che masculine ideal of selfhood is also found in socialist and humanist-Marxist feminism when rhe emphasis is placed on the human as a producer or worker (Plumwood, 1993, see also Grosz, 1990b). The second model Plumwood calls 'rhe feminism of uncritical reversal'. This is where femio.isrs are seeking ro give a higher value ro the female side of the female/male binary. This n1odel is mainly a~sociared with the marernalisr stance of culn1ral feminists w riting in the 1970!> and early L980s. This chapter exp lores rhese issues and debates and their in1plications for conceptua lizing equa lity in the following ways. The first cwo secrioos char follow a rc concerned ro understand equality as 'san1eness'. The firsr of rhese i!:> concerned wirh rhe mea!:>ure of sameness. What is rhivay's (2000) exploration of trade union work. T rus illustrates how service is predicated o n care w ithin relations of exchange-based masculine cultu res. Franzway begins by noting that there is a distinction between feminine and masculine interp retations of the meanings of the trade union ethic of 'service to members' . T his is translated in masculine terms as defending wages a nd cond itions. It is enacted through · " toughness" understood as dedication and con1mitn1ent con1 bined with a hard, assertive personal style' (ibid.: 266) . As women , women officia ls are therefore positioned within a complex array of discursive meanings and practices. lf they are too

122

KEY CONCEPTS IN FEMINIST THEORY AND RESEARCH

tough , then they are perceived to be 'waspish'. If they are not tough enoug h, they a re perceived to be 'w impish'. Franzway's ana lysis ind icates how won,en officials negotiate this terrain. Specifica lly, ' Fro m throwing the1nselves into a wholehearted bur unrestra ined care, rhey report shifts into a more discriminating, perhaps instrumental, or utilitarian exercise of care ... Overall, the women officials consrrue rnking care in terms of empowen11ent rather than of helping' (ibid.: 266-7). Similarly, Thorn ley's (1996) ana lysis of care in nursing illustrates bow care is divided into in1porrant skill distinctions. Recent changes in the training of nurses has given much greater emphasis on higher ed ucation qualifications as a means of restricting entry to, and enhancing the status of, nursing. Such entry qualifications neither value no r recognize prior caring experiences in rern1s of the caring for one's c hildren or parents. In addition, this approach to the training of nurses places cure above care through a focus on rhe acquisition of technical rather than communicative kno wledge. Although tbe predominant n1eanings of care giL'ing in family 1·esearch have focused on its oppressive and unrelenting nature, in employment contexts certain forms of care have n,ore recently been seen as an oppo rtunity for women. This is because rhere has been a shift from what has been termed ' hard' discourses of human resource management co 'soft' discourses (Legge, 1995) ' H ard' discourses considered employees as passive re posito ries of the o rde rs of their supe riors. The emphasi. \.Va on forrns of managen1ent that were autocratic and authoritarian. The discou rses of 'soft' hun1a n resource mana.get11e nt use terms such as e1npowennenr and teamwork to convey a libera tory and ega litaria n backd rop to rhese new n,anagemenr techniques. The core kiJls of ca re ar the centre of 'soft' human resource discourses a re those associated with relationaliry. Ofte n termed 'people management ski lls', they include listening, discussing, raking an interest in and faci litating. As a discourse char is designed to fir with flatter o rga nizationa l trucrures and c;o to some exrenr challenge traditiona l hierarch ical rel a tions between managers and workers, further -kills that are required are chose of subordinating o ne's ego and needs co chose of others. These are