Jaguar Saloon Cars 0854295968, 9780854295968

“652 p. : 28 cm Ill. on lining papers”.

123 38 82MB

English Pages 664 Year 1988

Polecaj historie

- Author / Uploaded

- Paul Skilleter

- Andrew Whyte

- Categories

- Technique

- Transportation: Cars, motorcycles

Citation preview

i

pet

Anes

AG UA CO

ONNGNRS ER

‘Grace:

=

Space

—

Pace’

wa;

the

unusually

trenchant sales slogan used for so many years by Jaguar to describe their saloon cars. It sums up not only the essence of the cars themselves but their reason for existence — Sir William Lyons’s determination, right from the early days of SS, to deliver luxury motoring at an affordable price. In Jaguar Saloon Cars Paul Skilleter tells the story of Jaguar from its beginnings. in the carly nineteen-twenties when William Walmsley — already building sidecar- — moved to Blackpool and was joined by the young William Lyons to form the Swallow Sidecar Company on an overdraft of £1000. Success in building sporting sidecars led to the construction of special sporting car bodies, first on other manufacturers’

chassis

and

then, after the in-

corporation. of SS Cars in 1934, for their own cars. The technique of using many proprietary components, bought-in at preferential prices, and incorporating them in stylish bodywork allowed Lyons to offer exceptionally attractive motor cars at previously unheard of prices. This formula was to prove the springboard for the success of SS and the mainstay ofthe later Jaguar company. Jaguar Saloon Cars has become accepted as the definitive

work

on

the

subject,

and

is

a

companion to Paul Skilleter’s other highly successful and award winning book Jaguar Sports Cars. It is not only a fascinating story of private enterprise and powerful personalities, but is first a comprehensive record of everySS and Jaguar ~ saloon model ever made. When Jaguar Saloon Cars was first published the very existence of the Jaguar name was hanging in the balance. Now, eight years on, the company and the name have achieved a staggering revival. In this second edition Jaguar’s achievement is charted and the history of the saloon cars brought right up to date. Included is information

on

the ultimate Series 3 cars, the XJ-S

cabriolet and the AJ6 engine, and there is a complete new chapter on Jaguar’s world-beater, the new XJ6. In addition the competition chapters have been updated by Andrew Whyte. Front cover photograph by David Sparrow Rear cover photograph, of the 1935 SSI Airline, kindly supplied by the ICS History ofJaguar Museum UK

Price..... £29.95

EAST SUSSEX COUNTY LIBRARY

Bee

This book must be returned on or before the last date stamped

below to avoid fines.

If not reserved, it may be renewed at the

issuing library in person, or by post or telephone.

No fines are

charged as such for overdue books borrowed by children from the Children’s Departments but a notification fee is charged in respect of each overdue notice sent.

A Pars

|

COUNTY

yo Tea ee

BOOK

Qi

RETO

URN

| 28SEP2009 COUNTY

20 MAR1997 COUNTY

STORE

Please protect this book from damage and keep it clean. A charge will be made if it is damaged while in your care.

cL/130

Form

iil

Paul Skilleter

‘

with competition chapters by Andrew Whyte

Es

This book is a companion volume to

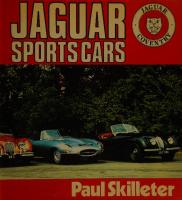

‘Jaguar Sports Cars 2nd Edition by Paul Skilleter (F453), in preparation Together with the following Foulis titles, they form a comprehensive history of Jaguar:

Jaguar (F277) Jaguar (F319)

Sports Racing & Works Competition Cars to 1953 by Andrew Whyte Sports Racing & Works Competition Cars from 1954 by Andrew Whyte

ISBN 0 85429 596 8

A FOULIS Motoring Book

First published April 1980 This second edition published 1988 © Paul O. Skilleter & Andrew J.A. Whyte 1980 & 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright holder.

Published by:

Haynes Publishing Group Sparkford, Nr. Yeovil, Somerset BA22 7JJ

Haynes Publications Inc. 861 Lawrence Drive, Newbury Park, California 91320, USA

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Skilleter, Paul Jaguar saloon cars. 1. Jaguar automobile—History I. Title 629.2’222

TEZNS.J3

ISBN 0-85429-596-8

Library of Congress catalog card number 87-82840

Editor: Rod Grainger Layout design: Rowland Smith & Joe Fitzgerald Artwork production: Graffiti Printed in England by: J.H. Haynes & Co. Ltd

-

2

[

ES re

Ries

wt ws

SEX

“id ‘

4)

FOES BAR

Contents Introduction

Acknowledgements

Chapter Thirteen The International Alpine Trial

11 Chapter Fourteen The Monte Carlo Rally

Chapter One Swallow

15

Chapter Fifteen

487

The R.A.C. Rally

Chapter Two The S.S.I and II

29

Chapter Sixteen

493

The ‘Tour de France’

Chapter Three The first Jaguars

63

Chapter Seventeen A European Rally Championship

501

Chapter Four The ‘traditional’ years

87

Marathons,

Chapter Five The Mk V Jaguar

133

and Monza

Chapter Nineteen

1a

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Seven Jaguar’s first ‘compact’ — the 2.4/3.4 saloon

M.P.H.

Silverstone in VIIs

Chapter Six The Mk VII, VIII and IX Jaguars

Chapter Eighteen

UK domination — the ‘compact racers’

ZA

2d

Chapter Twenty-one Racing around the World

547

Chapter Eight The Mk II Jaguar

241

Pa gh

Appendices

Chapter Ten The Mk X Jaguar

297

Appendix One: Specifications and performance data S.S. and Jaguar fourseaters

Chapter Eleven The First-Generation X] Jaguars

563

XJ in action

Chapter Nine The S-type and 420 saloons

Chapter Twenty-two

G2)

1931

to 1988

oO]

Appendix Two: Production figures, years current and prices

631

Chapter Twelve

The XJ 40

433

Index

637

ntroduction This book was literally on the presses when the shocking news came through of Andrew Whyte’s sudden death, at the age of 51, from a heart attack. I was at Jaguar’s Browns Lane factory at the time and I was waiting for him in the limousine shop: we were collaborating on an article for the new Jaguar. Quarterly magazine which editorially we were producing together. But all thoughts of such ventures were banished on hearing the news — I had just lost one of my best friends, someone who had been an inspiration and who by example and by gentle suggestion had had an enormous impact on my own approach to writing about Jaguar. This was my own first, selfish, reaction but the real loss is born by his family: Wendy, cruelly widowed for the second time, and her daughters (Andrew’s step-daughters) Louise and Sarah. One can only hope they will take some small comfort in the fact that Andrew’s own writings will be a lasting memorial to him: he will never be matched in his field, and the whole Jaguar movement owes him a huge debt. Read this magnificent contribution on Jaguar saloons in competition in this volume: in detail, accuracy and breadth it will never be equalled. Enjoy it, and pay your own respects to one of the greatest figures in the Jaguar world. P.S., May 1988

Introduction to the Second Edition

The first edition of this book went to press two months before John Egan arrived at Jaguar. Since that ime much has changed at Browns Lane, and in early 1980 it would have been beyond imagining that within four years Jaguar would not only be making an annual profit of approaching £100m, but would also be an independent company again. How wonderful that Sir William Lyons should have lived to see that happen; it was very noticeable how, as Jaguar pulled itself out of the mire, Sir William himself was brighter and more cheerful during his last months. Sir William died on 8 February 1983 at the age of 83; the founder of Jaguar Cars had gone — but not before he had handed the torch to a worthy successor in John Egan. The two men had spent much time talking and it is to Sir John’s eternal credit that he did not, as so many new leaders have done in various fields, reject all the old

ledgement of his work for Jaguar, as I learn more about his career it becomes increasingly apparent to me that the full contribution he made to the success of the Jaguar car is not yet fully appreciated. For Bill Heynes was far more than the company’s chief engineer. His contribution, especially, perhaps in the critical post-war years, was enormous and it was Heynes who co-ordinated and progressed for Lyons the whole difficult business of

thinking but instead listened, and learnt, from what had

getting Jaguar operational again after 1945 and turning

gone before. He even read books like this one! Sir John’s management techniques may be up-to-the-minute, but

the new post-war range of cars into reality. This was all | over and above his crucial part in designing the XK engine and in the design programmes that resulted in the Le Mans winning C- and D-types, and in the engineering systems which carried Jaguar through more than three decades, right up until the launch of XJ40. The arrival of XJ40 was, of course, the most significant event at Jaguar since the original XJ6 of 1968. Naturally a full description of the new car is included in this edition,

he has also contrived to retain the true Jaguar culture, so that ‘his’ Jaguars have remained ‘real’ Jaguars. In my view it is this blending of modern methods with traditional Jaguar virtues that is Sir John’s greatest achievement. It mirrors the achievements of his engineers in continuing to reconcile other aspects — technical ones, like combining superlative handling with an outstanding

/

ride — which might have been considered by others as incompatible. James Randle, Jaguar’s engineering director, is similarly conscious of Jaguar’s heritage and considers the thinking of his predecessors extraordinarily good. He will mention Bob Knight, Walter Hassan and Claude Baily, but it is obviously Bill Heynes who commands his greatest respect. I have been privileged to get to know William Heynes, CBE,

a

little,

and

while

there

is universal

acknow-

together with other new models which have come along since 1980, including the ‘High Efficiency’ V12 engined models,

the 3.6

XJ-S,

and

the convertible

XJ-S which

reached the marketplace at the same time as this book. These new models, and the successful launch of XJ40,

paint an optimistic picture of the future for the newly independent Jaguar Cars plc. The path ahead may not always be smooth,

but at least it is now

clearly visible;

and that certainly wasn’t the case when I concluded my 1980 introduction... Meanwhile, further exciting developments are underway at Browns Lane and, who knows, when in five or eight years’ time a third edition of Jaguar Saloons arrives, maybe we'll be discussing four wheel drive and possibly even a true successor to the Mk 2 saloon at last. We shall see! Paul Skilleter Hornchurch, Essex January 1988

involved in this book to be any less fascinating than that undertaken

for Jaguar Sports Cars.

But

it has certainly

proved to be more complex, largely due to the greater number of models, which themselves have grown in complexity as the motor car has become ever more sophisticated. As with Jaguar Sports Cars, I have tried to describe each car not only in terms of its design and specification, but also from the point of view of what it is like to drive and own — both in its contemporary surroundings when new, and today. The reader will also find that in most cases the cars have been compared with their rivals of the

day, and that where they have been found lacking, I’ve recorded this too — for only in this way can their true characters emerge. I’ve been enormously fortunate in persuading Andrew Whyte to contribute the competition chapters of this book,

which

he has done

despite heavy commitments

which include several long-awaited Jaguar titles of his own. So for the first time, the competition career of the

Jaguar saloon has been laid out clearly and in great detail, and I for one have found it fascinating reading. Introduction to the First Edition

Andrew is, of course, uniquely qualified to write about Jaguar, having worked at Browns Lane for many years

Those who have read Jaguar Sports Cars will know what to expect in this volume, as I have followed much the same pattern. Each chapter therefore deals with one particular model or family of models, more or less

(though he is currently freelancing in the motoring field);

chronologically — and if because

of this some

back-

ground history is occasionally repeated, then I’ve allowed it to do so in order to ‘set the scene’ in each case.

The Jaguar saloon (or sedan to my American friends) has always been the major preoccupation at Browns Lane, and Sir William Lyons has always concentrated his main efforts and ambitions on the company’s successively more impressive and refined closed models — the sports cars have really been subsiduary products, manufactured in smaller numbers and indeed only made possible

through the use of components developed for the saloon

also, he has himself covered a number of the national and international events he describes, including some while

on the staff of Motoring News. Both Andrew and I have been greatly helped in our task of recording the history of the Jaguar saloon by the car’s own excellence — again and again, the Jaguar’s superiority over most other cars in its class (if indeed there were any) shows through clearly, whether in performance,

refinement,

competition prowess or sheer style.

Thus this book must emerge as another tribute to the man who began it all, Sir William Lyons, and to the team

of designers, engineers and shopfloor workers who over the years have turned his unique concepts into successful realities.

car range. Thus to the factory, and to the historian, this book is probably a more important work than my pre-

ceeding one on the open two-seaters, even if at first sight the subject appears to be less glamorous. Personally, I am an enthusiast for every type ofJaguar, open or closed, and I’ve certainly not found the research

10

Martley, Worcestershire

February 1980

Acknowledgements

These were some of the men who produced the car, but

With a book the size of this one, written over a number of

years, it is an almost impossible task to acknowledge and adequately thank all those who have willingly contributed material and time. Inevitably there must be some names which memory

fails to recall, but I hope these will feel

it is largely through the comments of the contemporary motoring press that we evaluate the status and success of a vehicle in its own time. Thus we motoring historians owe an

enormous

debt

to journals

such

as Autocar,

Motor,

included in my general thanks to everyone who has made

Autosport and Road & Track. Having been privileged in the

this book possible.

past to work for Motor for some

To begin at the factory, I must record my gratitude to

those who cheerfully put up with my numerous visits to

Browns Lane — particularly Alan Hodge who took the brunt of them, and who with his small enthusiastic staff in the Special Facilities Department never failed to meet

even my most obscure requests.

Of the engineering staff at Browns Lane, my thanks must go to Tom Jones whose responsibilities lie in chassis development, and who devoted valuable time answering questions on all the post-War range. I would also like to put on record the part which the late Peter Craig, Plant Director, played in my researches; one of the busiest, and

most loyal executives at Jaguar, his contribution was vital in recording the company’s post-War history. As a person too he made a deep impression on me, and his premature

death in 1977 was a tragedy. Of those no longer working at the factory, I must thank Claude Baily for spending hours answering my questions on the evolution of the XK and V12 engines, in which he played a vital part — as did Walter

Hassan,

who

endured a layman’s questions on engineering subjects.

also

nine-years, I know at

first-hand the meticulous hard work which goes into the compiling of road-tests published by these magazines, and the effort expended to ensure the accuracy of performance figures and all the other data contained in them. I would therefore like to extend my thanks to the editors of Motor and Autocar — Tony Curtis and Ray Hutton — for allowing me to use the archives of both journals. In particular I have spent many hours at the London office of Autocar researching obscure details right back to 1922, and am very grateful to Anne Palmer and Warren Alport for their patience and help. The pictorial content of this book has also relied to an important extent on Motor and Autocar photographs, and indeed it is not overstating the case to say that the negative archives of these IPC magazines amount to nothing less than part of our national heritage, such is their unique record of Britain’s motoring past. As a photographer myself, I would like to pay tribute to the skills of the

Temple Press and Iliffe Press (as they were) cameramen past and present who created these pictures — often inspite of appalling conditions, and in the face of 11

oe technical limitations unknown by many in the field today. I would therefore like to record the names of the late George Moore of Motor, Maurice Rowe and Peter Burn of the same journal, and Ron Easton and Peter Cramer of

Autocar; not forgetting the photographic department staff at Autocar, including Len Roffey, Bill Banks, Bill Heasman

and Mary Smith. A large proportion of the pictures in this book came from Jaguar’s own archives though, and I’m very grateful to Roger Clinkscales, head of the photographic department at Browns Lane, for allowing me to spend many days sorting through old negatives — without the extension of this unique privilage, Jaguar Saloons Cars would only have been half the book that it is. Leaving the motoring press and Jaguar, I would like to thank Mr MacVitie of Rothwall and Milbourne (one of Jaguar’s oldest-established dealers) for the loan of vital service records going back to 1946, which helped enormously in chronicling production changes to post-War Jaguars. Then Mr and Mrs Christopher Jennings once more spent some hours recalling early $.S. days, while Alan Gibbons of the S.S. Register, and S.S. restorer David Barber, both contributed a vast amount of detail to the

story of the pre-War Jaguar and S.S. David Middleton also assisted on the subject of the rare Jaguar tourer, while Geoff Shimmin gave me the benefit of his intimate knowledge of ‘Mk IV’ and Mk V cars. Jack Rabell, ‘Mk IV’ Registrar of the Classic Jaguar Association, contributed much ofinterest on these cars too. Also from the States, I am indebted to Paul Borel and

Tom Hendricks for large quantities of rare Jaguar literature which played an important part in piecing together the story over there. Ed and Karen Miller from the same continent, and Ron Beaty of Forward Engineering here at home, helped with XJ material, while Ron also regailed me with many illuminating stories of his years as an experimental engineer at Browns Lane. Amongst the many others I would like to thank are: John Bolster, Tom March, Roland Urban, Philippe Renault, John Harper, Graig Hinton, Raymond Legate,

Alan Townsin, Les Hughes (himself author of a book on Jaguar’s Australian history) and Heinz Schendzielorz (of Victoria, Australia).

Then I must single out Andrew Whyte for not only contributing the entire section on Jaguar’s competition history (see Introduction), but also for guiding me through Jaguar lore generally, and helping me. differentiate between fact and fiction. Andrew also gave generously of his own painstaking research into S.S. and Jaguar production figures to help complete Appendix Two. To my publishers, especially John Haynes himself, I

would like to extend my thanks for patiently awaiting a lohg-overdue manuscript, and for assimilating almost twice the number of words originally agreed upon... I’m grateful to Tim Parker for originally offering me the con12

tract, and to his successor Rod Grainger who has had to cope with me thereafter. Finally, this book has not been completed without much sacrifice by my wife June who has been supplanted by my typewriter for the past three-years. If this book is a success, it, will be largely due to her support and

understanding — quite apart from her own contributions in the form of the Index, and in weeks of copy-reading. P.O.S.

February 1980

Acknowledgments to Second Edition The bulk of the research which makes up this new edition was compiled with the aid of the people mentioned in the original Introduction

but, of course, many others have

been involved since in the preparation of new material, especially concerning XJ40 and the new XJ-S variants. I would like to begin again at the factory and thank Sir John Egan not only for his assistance in the past but for ensuring that we Jaguar historians will have lots to write about in the future! I’m grateful to. the current engineering staff at Jaguar for spending time explaining to a non-engineer the intricacies of XJ40 design and development, especially Jim Randle, Trevor Crisp, Rex Marvin,

and

Richard

Cresswell.

Paul Walker

provided

information on 3.6 XJ-S development, and Colin Cook of the public affairs department was of great help in obtaining factory data, as was the ever-willing Ian Luckett of the Special Facilities department at Browns Lane. I would like again to acknowledge my debt to Bill Heynes, who has consistently spent much time patiently recalling how earlier Jaguars were evolved. ‘Lofty’ England has also once more contributed information and ‘de-bugged’ parts of the manuscript in his usual masterly style, and, of course, Andrew Whyte has updated his suberb review of the Jaguar saloon in competition despite heavy commitments to further new titles of his own (which include the second part of his overall history of ‘works’ involvement in competition, and a book entirely on the XJ40). Gilbert Mond of the Austin Swallow Register ‘overhauled’ Chapter One and made a number of welcome suggestions on the early years. At Haynes Publishing, it is now Mansur Darlington who has to suffer my chronic inability to keep to deadlines, but to whom I’m very grateful for his polite and consistent pressure, without which there might not have been a second edition of this book! And finally, it is my family and in particular my wife, June, who have had to endure long hours on the typewriter when house, garden and even cars have desperately required my attention. Again, without such a back-up at home, this revision might not have been completed.

P.O.S.

January 1988

Part One

The design and evolution of the S.S. and Jaguar saloon

Chapter One

Swallow ... there is no wonder that so many youthful belles find a Swallow just the very thing to make life complete and well worth living. The Autocar

[ Mr. Thomas Walmsley had not decided to close his coal merchant's business in Stockport, Cheshire, and move to one of the better districts of Blackpool, that popular seaside resort on the Lancashire coast, it is just

1920,

this

meant

purchasing

crates

of War-surplus

Triumph motorcycles, pulling them apart, and selling the

possible that the Jaguar story would never have happened. But he did, and unwittingly brought about the meeting between two young motorcycle enthusiasts that

reconditioned models to a public which had an everincreasing appetite for almost any form of mechanical transport. Then, innovation! Dissatisfied with merely turning out the same old bikes as everybody else with a spare shed

was ultimately to effect the whole British motor industry.

and a set of spanners, Walmsley took his first step into the

realms of coachbuilding — his machines began to appear, aie ste aie

in very small numbers, with a sidecar attached; and very

attractive the ensemble looked too.

The true beginnings of Jaguar can still be traced back to the busy town of Stockport, just seven miles from the

His cousin, Mr W.H. Axon, then a young apprentice at Talbot Garage, Stockport, well remembers watching the

great city of Manchester in the smoke-laden air of the still coal-burning industrial midlands. There, Tom Walmsley would leave his main depot at Reddish station and travel back to his house a little way out from the town centre at

first sidecar come together in the summerhouse of the big detached house at Woodsmoor, with Walmsley being assisted by his future brother-in-law Fred Gibson. The

Woodmoor; ‘‘Fairhaven’’ it was called, with the pastural address of Flowery Fields, and on his return he might well

pram-shaped encumbrances usually foisted on the twowheeled brigade by the dozen-odd sidecar manufacturers of the period, who had only just grown out of the wickerwork bath-chair approach to the subject. Walmsley’s sidecar was finished in gleaming, polished aluminium, with eight separate aluminium panels mounted on an ash frame to form an octagonal, bulletshaped carriage which has often been likened to the Zeppelin — an all too recent memory in the 1920s. The tubular chassis was ‘bought-out’ from the Birmingham firm of Haydens, the wire wheel usually being covered by

have been greeted by the spluttering bark of a motorcycle being started up — son William had had an early tea and was off to visit his girlfriend on his noisy Triumph again The Walmsley’s were a well-to-do family, and William

had plenty of spare time and pocket money to indulge his love of tinkering with things mechanical. The Great War was only a couple of years over, and swords were still

being beaten into ploughshares: for William Walmsley, in

finished

result was

impressive,

and

not at all like the

15

a polished aluminium wheel disc which heightened the modern, streamlined effect. Mr Axon recalls that the very first ‘Swallow’

sidecar

built was registered with its motorcycle at Stockport Town Hall on January 28th 1921, the bike carrying the number DB 1238. Several more appeared to have been made at Stockport, still very much on a home-made basis with the

trimming being done by Walmsley’s sister, and then his wife after he married. Befitting its limited production and high quality, the Swallow sidecar was expensive; a basic

price of £28 being quoted, with £4 extra for the rather claustrophobic hood, a lamp and wheel disc. It was sold locally, by word of mouth it seems, with the claim that it was ‘“‘Made to sit in, not on!’’. At the most, one a week was completed, and there didn’t appear to be much

chance of this modest

rate of production

increasing

drastically.

Then came the move to Blackpool, and a change of scene. King Edward Avenue, almost within sight of the sea front, is made up of large, solid, brick-built houses

with grey slate gabled roofs and bay windows. Number 23 must look now very much as it did in 1921 when the Walmsley family moved into its new home — a typically

respectable,

middle-class

Englishman’s

semi-detached

residence set in the better side of town. At the end of the

Behind number 23 was this little alleyway, and in these

garden adjacent to a lane, there was — and still is— a small

outbuildings Walmsley constructed his sidecars. The young

Walmsley’s Blackpool home at number 23 King Edward Avenue, photographed as it is now but little changed from the early 1920s. Outside this staid, middle-class residence would often be parked a gleaming new sidecar combination, a centre of attraction for every boy in the district. Photo: P. Skilleter

William Lyons became a frequent and keenly interested visitor. Photo: P. Skilleter

brick outhouse, barely large enough to accomodate more

than a couple of cars, and it was here that William Walm-

sley recommenced his sidecar activities. Almost in the next road was another motorcycle enthusiast who didn’t fail to notice that dashing silver sidecar which was often parked outside the new arrivals’ house; his name was, of course, William Lyons, the only

son of a Blackpool piano and music shop owner. Before long, he too, joined the small group of Swallow sidecar owners. However, his interest did not stop with ownership; the twenty-year-old Lyons was keen to enter

‘the trade’, for besides his motorcycle racing activities — with such machines as Nortons and Brough Superiors at the nearby Southport Sands — he had also tried car salesmanship. So it wasn’t long before he realised that the Swallow sidecar might well represent the business opportunity he was looking for, as he was certain that the product deserved a much larger market than the one Walmsley was catering for. Walmsley agreed with Lyons’ ideas for expansion, and obviously thought that it would be very useful to have the go-ahead youngster around to look after the paperwork and see to the business side of his activities. Certainly it can be said that William Walmsley always remained far more interested in designing and tinkering with things than he was in becoming embroiléd in the organisation and structuring of the company that was being formed. 16

_ t nen

[ate |

The Swallow Sidecar Company came into being on September 4, 1922 — it might have been a little earlier except that it was found that Lyons hadn’t reached the

legally required age of 21 (Walmsley was then 30). Finance for the project was in the form of a £1000

overdraft facility guaranteed jointly by Tom Walmsley and William Lyons senior, both parents thus expressing much

confidence

in the scheme

(this sum

would

have

purchased a four-bedroom house in those days). The first step was to find better premises, and soon the business was in full swing at 7-9 Bloomfield Road, a tall, narrow building of drab brick, old even then but which

stands to this day. Swallow had the two upper stories, and with a workforce of six or seven men, production of sidecars increased rapidly. So rapidly in fact, that within a

year part of awarehouse in Woodfield Road was acquired While this picture shows a later model, it illustrates well the

for the despatch department, and soon afterwards a two-

impressive mirror-finish aluminium ‘zeppelin’ styling of the

storey corner building in John Street, almost opposite the

Swallow sidecars, and it is easy to see why they attracted purchasers.

main factory, also had to be leased.

Within a year ofstarting business, Swallow were exhibiting at the Motorcycle Show, and as time went by could display a wide range of ‘chairs’; Swallow sidecars were also adopted by such leading motorcycle firms as Brough Superior, Dot and Matador.

!

Ntbeess PERUSE URIS CIV ANGye5 4, on

17

09908 a7oua ia

Swallow’s first factory was at Bloomfield Road (top), but soon had to be supplemented by premises at Woodfield Road (left) and John Street; all were leased not bought, of course. Photos: P. Skilleter

18

Much more space was created by a move in autumn

1926 to Cocker Street; sidecar production was expanded and coach painting and

trimming taken on as a prelude to proper coachbuilding. This is the building as it is today. Photo: P. Skilleter Sidecar construction at the Coventry works. Considering the amount of handwork employed it was a very streamlined operation, with

a capacity of 100 or more units a week. Note the small jig in right foreground used for slotting together the sidecar frames. Photo: Jaguar Cars

ee

19

Oo Not everyone would have predicted this success — cars such as the Bullnose Morris and the new Austin Seven

threatened to bring cheap motoring to all, and it was being said that this competition would be too much for the spartan sidecar. Ultimately this would be a correct prognostication, but not for another 40 years; in the early 1920s, the Swallow Sidecar Company flourished with

The Austin Seven is one of Britain’s greatest small cars, and one of the major reasons for its success was that it renounced the ‘cycle-car’ approach to cheap motoring — with all its attendent

cooled

horrors

of chain drive, noisy air-

engine and bent-wire-and-canvas

coachwork —

and instead was, in effect, a large car scaled down. It had

production of an expanded range of sidecars creeping up

a ‘real’ engine, a water-cooled four-cylinder, two-bearing unit of 696 cc (later 748 cc), four wheel brakes (though

towards

100 units a week and, with yet another project it was soon time to search for even larger premises. These were found in a considerably more modern

until 1930 only the fronts were worked by the footpedal,

building than the one in Bloomfield Road, situated in a

millions’, and helped to bring motoring to all, remaining in production (with various changes) up until World

around

the corner,

quiet, semi-residential area of Blackpool and formerly occupied by Messrs Jackson Bros and previouslyJ. Street,

“Motor Body Builders, Est. 1896’’. It was on the corner of

Cocker Street and Exchange Street (both names were usually included in advertisements, making it sound more impressive), and the centralising of operations certainly helped production — which, incidentally, was somewhat seasonal in that demand for the sidecars reached its peak on three separate occasions in the year, Easter, Whitsun,

and

August

Bank

Holiday.

This

meant

that

while

manufacture continued at a fairly even pace, during those three periods every spare hand was set-to in the despatch

department, packing and crating the completed sidecars. Meanwhile, the motor industry itself had been suffering a number of setbacks as the depression took hold in Great Britain, finally manifesting itself in the General Strike of 1926. One large well-established company which

the

rears

by the

handbrake!),

a

good

three-speed

gearbox, and efficient if basic coachwork capable of holding four people. It was indeed, ‘‘the motor for the

War Two.

Lyons and Walmsley were more than aware of the Austin Seven’s success — after all, while their sidecar order books showed otherwise, the new generation of light cars

which the Seven looked like inspiring might ultimately ring the death knell of the sidecarriage. In any case, their sights were set on expansion and the Seven appeared (literally) to be the vehicle. As with virtually every production car oFthose days, the Seven was based on a separate chassis frame, with the

coachwork being dropped onto it as a complete (and usually

prefabricated)

unit.

In the case

of expensive,

luxury motor cars, the manufacturer might only supply the running chassis, which would then be fitted with coachwork to the customer’s requirements at an independent coachbuilders. Swallow decided to combine

suffered was the Austin Motor Co Ltd at Longbridge, Bir-

the two approaches — acquire the running chassis of a

mingham,

but was pulling through helped to a large

cheap motor car, and fit it themselves with a completely

extent by Herbert Austin’s new ‘baby car’, the Seven, which had been launched in 1922 — the same year as the Swallow Sidecar Company.

new, high quality body of fashionable design. The end

This snapshot of a rather modified Swallow from

Jaguar’s archives is captioned ‘the very first Swallow Seven’, but while it has the

cycle wings (which turned with the wheels) of the

prototype, it carries a 1928 production model radiator

cowling; so it remains rather a mystery!

20

result was a car that was still cheap to buy and maintain,

but was at the same time individual.

The Austin Swallow was soon refined into this rather more substantial vehicle, with a continuous wing line and running boards; a detachable hardtop with vent was a novel

Swallow was

‘extra’.

not the first company

to employ this

labour to be recruited from the industrial complexes of

formula, but they were undoubtedly the most successful.

Birmingham

The Austin Swallow Seven made its appearance in May

and

Coventry,

especially

men

with

car

1927, and an extremely pretty car it was too; it had been

assembly skills. To them, building the Swallow bodies presented little difficulty, although one or two short-cuts

given a neat two-seater body, with,a distinctive ‘bowl tail

had to be resorted to. For instance, the Austin’s radiator

and a rounded

filler neck was half an inch too high for the special Swallow cowl, and this problem was solved by placing a piece of wood on the neck and striking it sharply with a

nose,

built of aluminium

panels on a

wood frame. The Seven’s “A’ frame and mechanics were untouched, although to support the new body it was necessary to fit some angle iron at the sides; likewise, the

hammer, thereby depressing it neatly into the header tank

car’s transverse leaf front spring, and cantilevered quarter-elliptic rear springs, remained as they were. Outside, you certainly couldn’t tell it was an Austin, and of course the interior was completely new too; the plain Austin dashboard was supplanted by Swallow’s own mahogany version and new, comparatively luxurious, seats were installed. There was a detachable hardtop if required, which added £10 to the modest price of £175. This low initial cost, coupled with perky good looks and a touch of exclusivity, ensured that the Swallow Seven became an instant commercial success. The extension of Swallow’s skills into the motor car market required yet more staff, and it was necessary for

by the required amount! “I am sure Sir Herbert Austin, as he then was, would not have approved, although it was a perfectly sound job!”’, wrote Sir William years later.* That stylish radiator cowl which was so much a feature of the early Swallows brought another minor problem — the Austin starting handle which tinkled about at the front was not long enough to clear it, and an old Blackpool hand recalls having to hacksaw through the oneinch steel and re-weld it with an extension let in! All by hand at first, although it is also remembered that Lyons was constantly searching for more efficient ways to do things, and would introduce a machine to do a job wherever he could.

* This little anecdote may relate to Austin’s introduction of a taller radiator in May 1929; earlier original cars show no signs of this ‘dinging’ today.

ye

Above: Ever enterprising, Henlys

offered this ‘package deal’ of Austin Swallow and outboard motorboat;

with luggage too (housed in the

rounded tail along with the spare wheel) hills couldn’t have been too much fun on the way to the seaside! Photo: Autocar

Right: Probably only one Morris Cowley Swallow was built, but

as this Swallow

catalogue picture shows, it was quite a

large and handsome car. A young Alice Fenton poses in the driver’s seat.

programme a couple of years earlier, Swallow elected to

‘““My visit to Henlys was the occasion of my first meeting with Frank Hough and Bertie Henly, the two partners. Hough was a dynamic man with a determination to do things quickly; Henly was the steadying influence and he

use the 1550cc Cowley but, perhaps because of the success achieved by Kimber’s factory-backed project, the two-

William.

By mid-summer 1927, there was a brief excursion into another make - Morris. Instead of the 1.8-litre Oxford with which Cecil Kimber had embarked on his MG

seater design evolved by Swallow for this chassis wasn’t , proceeded with, and it seems that few Morris Cowley Swallows were completed. Unfortunately, none appear to

have survived and even photographs of this Vwindscreened Swallow are a rarity. So, it was the Swallow Seven which gave the chance of greatly increased sales, and it was essential for Swallow to establish proper retail outlets. Accordingly Lyons drove a two-seater Swallow to London in order to visit a new and “forward thinking” business that had recently sprung up.

22

was also the finest salesman

I have ever met’’, wrote Sir

The deal concluded that day, at 91 Great Portland Street, far exceeded William Lyons’ best hopes, as in

return for exclusive distribution rights ‘‘... south of a line drawn from and including Bristol to the Wash’’, Henlys

gave him an immediate order for 500 cars! A somewhat amazed Lyons made the return journey to Blackpool,

wondering just how he was going to produce that sort of quantity, which was to include a saloon version, which Henlys thought essential.

Early and late Austin Seven Swallow saloons are shown here, the 1930 car nearest the camera having a wider radiator shell compared with the later 1931 or 1932 model just down the line.

The spindly ‘A’ frame of the Seven

undergoing bodymounting at Foleshill; it was used more or less as it arrived from the Austin Motor Company, with no

attempt at tuning or modification.

23

Before the ‘Lyons’ treatment, the basic off-the-shelf motorcar

looked like this — a 1932 Standard Big Nine in this instance, all very straight-laced and angular.

Body construction in Coventry, with panelling commencing as each frame is finished off; the aluminium tail of the two-seater

(on right of picture) was made up of some six individuallyshaped pieces of metal welded together, the welds being ground down and hand-finished to produce invisible seams.

The pressure was now really on, but although production rose to nearly 12 cars a week (plus well over 100 sidecars) it became obvious that for reasons of space and the right sort of manpower, another move would have to be made. There were also subsiduary problems, such as

Longbridge despatching chassis orders in bulk and causing much consternation at Blackpool Talbot Road Station,

as

it was

impossible

for

Cocker

Street

to

accomodate the full consignment, which to the great displeasure of the stationmaster meant that rolling stock and sidings were tied up for weeks! There was only one place to go, and that was the midlands car manufacturing area of Birmingham/Coventry with its pool of skilled labour and every type of industrial facility. Thus Lyons set out to reconnoitre the Coventry district, driving from Blackpool in his own

Swallow Seven (flat out all the way, “including the

corners’’, by his own recent admission!) to investigate likely sites. The most promising turned out to be what had been a shell-filling factory at Foleshill, on the Nuneaton side of Coventry; these Holbrook Lane premises comprised four

separate buildings, two of which were being used by a firm supplying fabric bodies to Hillman, but the other two were empty. The owners were keen to sell outright, but Lyons managed to obtain a lease instead. “It was five times larger than the premises we occupied in Blackpool and I felt it was a tremendous step forward”’. A lot of work was needed on the building itself though, which was in ‘“‘terrible condition’? — the contractor’s quote for repairing it was five times greater than 24

Swallow’s total assets (!), so a gang of labourers was engaged and the place was made shipshape by the company itself — which had been retitled in 1927 as the ‘Swallow Sidecar & Coachbuilding Co.’, this more accurately reflecting its activities. The move to Foleshill was completed by early November 1928, but all did not go smoothly at first — almost

unbelievably it was discovered that the main electric feed cable had been stolen, and even worse,

it cost £1200 to

replace. Then very inconsistent results were obtained from the new steam-bending equipment used for the body frames, and it was only through the arrival of Cyril Holland — the coachbuilder who had originally sketched out the Swallow Seven but had sought to stay in Blackpool — that total disaster was averted. However, with these difficulties resolved Sir William recalled that: “It was a most exciting time. We worked from 8 o'clock in the morning until 11 or 12 o’clock at night, for we aimed to raise production from 12 a week to 50 a week within three months. We knew we could only do this by adopting a new method of coachbuilt construction .... Whereas in Blackpool each body-maker had been responsible for the complete framing-up ofthe body, the latest method used for volume production was the machining of the wooden parts in specially constructed jigs, so that they could be assembled rather like a jigsaw puzzle. “This saved a tremendous amount

of labour, but the

introduction of the method caused us many headaches. In fact, we were in such trouble at one time that the body-

makers approached me en bloc and told me that the whole

thing was too complicated and doomed to failure, and

allowed to continue with the six-cylinder design and in

that we should resort to the old method. We perservered,

April 1930, the Wolseley Hornet was announced. Rather in contradiction of its quite advanced

knowing that the economies could be very considerable, and before Christmas we had achieved our 50 bodies a week. We were really in business !”” Lyons also transferred his search for efficiency into Swallow's wages structure. In a manner somewhat ahead

mechanical specification, no sporting versions were offered, just the rather uninspiring saloon. No wonder then, that it attracted coachbuilders in droves - by the end of 1930, these included the Hoyal Body Corporation,

of his time, he made a time-study of all the major opera-

Gordon

tions on the assembly line, priced them according to the

Boll, Coventry Motor & Sundries Ltd, Avon, and Whitt-

England

with beetle-backed

offering,

Hill &

time allowed for each, then printed books of vouchers.

ingham & Mitchell who were under contract to London

There was one book for each car, every voucher covering one or more of the operations and valued according to the price that job had been costed at. When the operation

Wolseley

had been completed,

voucher which, after it had been countersigned by the

than just a rolling chassis! Swallow, who entered the fray in January

foreman,

faced considerable

would

the man

be handed

wrote

his name

on the

in at the end of each day.

Then all that the single wages clerk had to do was add up the value of each operative’s vouchers and make up his wage packet accordingly. Not everyone liked these various schemes, particularly those amongst the newly

distributors

enthusiasm October

Eustace

notwithstanding

the

Watkins.

All

fact

prior

that

this

to

1930, one had to purchase the entire car rather

competition,

1931, thus

but their tasteful treat-

ment of the subject, incorporating a rather beautiful pointed tail, has stood the test of time and the Swallow

Hornet

can probably be adjudged the prettiest of the

recruited Coventry people, but they found that it worked

bunch. Wolseley production improvements were included in the Swallow’s specification, so that from

and most stayed. In 1929, Swallow felt able to extend their range of

gearbox and three inches more track, which helped offset

coachbuilt bodies, and employed their tested formula on

a number of other ‘plebian’ chassis. These were the Fiat 509A (quite an advanced car mechanically with a 990cc overhead-cam engine, and a best-seller in standard form in Italy), the 1287cc sidevalve Standard Big Nine, and the Swift 10. The small Coventry firm of Swift possessed a sound

reputation

for reliability

if not

for excitement,

September 1931 the car was given a 4-speed helical tooth its rather high, narrow look. Two and four seater styles were by then catalogued by Swallow. Foleshill

also

adopted

the

Hornet

Special

chassis

announced in April 1932, with its new pistons givinga 6:1 compression ratio and duplex valve springs to accomodate its maximum rpm of 5000 - which equated to

a respectable 80mph odd in top gear . Bigger (9-inch to

although the 1190cc ‘P’ model used by Swallow had the

12-inch)

optional

remained

gearlever were also added to its specification, and the tail

faithful until the end, Swift could not withstand the com-

section of the bodywork revised. The Swallow Hornet Special cost £255 in two or four-seater guise, though in

‘sporty’ wire wheels;

while Swallow

petition from giants such as Austin and Morris, and ceased production in 1931.

brakes,

an

oil cooler

and

a remote

control

stylish wingline. Plus, most importantly, an imaginative

1933 the foursome went up by £5. By now, Maltby, Corsica, Hardy and Patrick had added their own designs to those already available. The Special chassis was always supplied without bodywork, incidentally, and Wolseley’s own apparent

choice of duo-tone

nine in all for the

lack of interest in producing a finished sporting version

Red/Maroon,

themselves can almost certainly be traced back to pressure from Morris Motors, who did not want in-house competition to MG. The Swallow Hornets, produced up until the end of 1933, were to be the last proprietory chassis rebodied by Lyons and Walmsley.

All were given the same basic ‘Swallow’ look, with a low roofline projecting over the windscreen (which was often in ‘V’ form), two doors, curved rear-quarters and a

1930

season,

colour schemes,

including

Cherry

Sky

Blue/Danish Blue, and Cream/Violet — a contrast to the normal choice of dark blues, bottle-greens, browns and

(mainly) black offered by most manufacturers. No wonder that the Swallow stand at the 1929 Motor Show - their first visit to Olympia — was usually crowded. The only car with sporting pretensions that Swallow ‘repackaged’ was the Wolseley Hornet. A victim of the slump, Wolseley had been taken over by Morris in 1927

while in the middle of developing a ‘small six’ engine of only 1271cc with the novelty of an overhead-camshaft;

the idea was to bring true six-cylinder smoothness to the mass market. Morris Motors Ltd took advantage of the work done and produced a four-cylinder version of the engine which, complete with ohc, was fitted into both the Minor and the MG Midget for 1929. Wolseley were

Rather

less sporting but much

more

significant in

Swallow’s development was the Standard Ensign 16, also of six-cylinders, which was announced from Foleshill in

May 1931. The Standard Swallow 16 was given similar coachwork to that of the smaller 9, including a radiator grille which clearly foreshadowed that of the S.S.1; but most importantly, it was the big, smooth 2054cc sidevalve

engine with its robust 7-bearing crankshaft that made the greatest impression on Lyons and Walmsley, and by the time the Swallow 16 was on sale, Lyons had already laid his plans for a very much more ambitious project.

/

25

Precursor ofthe S.S.I. was in many ways the Standard 16 which Swallow happily re-bodied; above all it introduced the company to the large, strong and smooth Standard 6-cylinder power unit. Introduced in May 1931, it cost £275, plus £7.10s extra if you

wanted a sunshine roof. This car was photographed recently by Stuart Sadd. Sportiest of the Swallows was undoubtedly the Hornet version; it was also about the most attractive of the open Swallows as this

photograph of this 1932 model two-seater demonstrates. Photo: Autocar

26

ie Meanwhile, the mainstay of Swallow’s production, the Seven, had not been left alone. Fixed front wings with half

Crosby of The Autocar visited Holbrook

Lane,

Dunlop,

to

valance had replaced the original cycle-type in September 1927, while for 1929 the front wings were given a full valance and a ‘dummy’ dumb iron cowling fitted beneath an altered radiator cowl which now incorporated the starting-handle aperture in the surround instead of the grille. The radiator cowls on these Swallows were, incidentally, polished aluminium. The Austin was given further attention for 1931, in the shape of a new radiator grille, the bulbous nose being replaced by a new design of shallower depth, wider at the

Swallow factory. Obviously intrigued and impressed by the company’s progress in the few short years it had been at Coventry, they had come to see for themselves the

bottom than the top, and with a centre bar. The assembly, apart from the honeycombe mesh, was chromium plated,

that type of finish having replaced nickel on Swallows in 1930. Cellulose paint was now being used too, instead of coach enamel and varnish. Scuttle ventilators of the picturesque

ship-type

became

fixtures

on

the scuttle,

these also being used on the Standard and Swift models. The Swallow Seven saloon had its split bench front seat replaced by individual bucket seats. It was in 1930 that Maurice Sampson and F. Gordon-

White

‘“Swallow’s

and

Poppe,

and

Riley

passing

reach

the

Nest’’, where, as Maurice Sampson put it, “‘a

well-known strain is hatched, matched and despatched”’.

Immediately noted by the visitors were the efficient methods of production described earlier, beginning with the saw mill. ““The saw mill in the Swallow’s nest is an extremely important part of the structure. In this mill every single piece of wood used in the frame of the body must be cut and shaped with such accuracy that all the pieces can be put together on a jig without the slightest hand fitting. On emerging from the mill the pieces are brought to the erecting shop, where, with two lads at each of the four erecting jigs, the pieces are put together, glued and screwed, and are off the jig in a very few minutes above one hour per body... The precision with which each piece went into place was quite fascinating to watch...” This rate of frame production — potentially 30 a day — could, Sampson observed, easily swamp the panelling

The Swallow stand at the 1930 Olympia Motor Show, featuring an example ofthe revised 1931-model Austin Swallow with its less bulbous nose and a central rib to the radiator. Next to it is a Standard Nine, and behind a Swift.

y

as

department next door, where progress was slowed by the necessity to produce a perfect finish on the aluminium panels, ‘‘a tedious and expensive operation...but properly flatted and rubbed down a finished aluminium panel is highly attractive and a thing of grace and beauty, as befits a swallow.” Next came the paint. “There is no false modesty about the colour schemes here. They are out to provide bright colours, and to do their bit to make our roads as gay as possible. You hardly ever see a one-colour Swallow on

to fit the body to the chassis. Then more polishing and a final look over, and the elegant ensemble goes into the big store-room to await the owner or his agent... I hope the weather is fine when the Swallows fly away from their nest. I should hate to think of their plumage being splashed as they pass over that dreadful bit of road between Dunlop and White and ‘Pops’ ere they reach Holbrook Lane.” Refinements

to

the

Seven

continued,

and

it was

announced towards the end of 1931 that safety glass was

the roads, just as you never see a one-colour swallow in

to be fitted all round,

the air. Just at present a combination of greens, or green and black, or green and white seem to be the most popular schemes.’ Trimming followed, the body then being taken out of the trim shop on a little hand-drawn cart to be mounted on its chassis. ‘“There are rows of

exhaust became standard fitments. At the same time eight new colour schemes were made available. Perhaps because it would soon become obsolete, prices of the Swallow Seven were dramatically reduced too, the saloon

Austin Sevens, Swifts, and Standard Big Nines waiting for their pretty burdens, and it seems to take very little time

from £165 to £150. For Swallow, coachbuilding were nearly over ....

28

and sports silencers and fishtail

coming down from £187.10s to £165, and the two-seater

the days of mere

Chapter Two

The S.S.I and II Let it be pointed out that these S.S. cars are not just built round a certain popular chassis. The design is original and distinctive. The Motor, January 31, 1933

wallow

had been hinting about a new car in the

motoring press ever since July 1931, when The Autocar

of the 31st of that month carried a very full description of “a marvellously low-built two-seater coupe of most modern line’ in a nicely controlled ‘leak’, describing accurately the salient features of its coachwork and mechanical specification. Lyons was certainly intent on

wetting the appetite of his potential customers well before the actual goods were on sale, and backed-up such

construction. No, the overriding impression one gains from distilling eye-witness accounts and written opinion both was that the S.S.1 was different - it “‘struck a new note’’ as an experienced journalist on The Motor recalled some years after it had caused that initial furore. There was

nothing quite like it, anywhere,

and

the motoring

pundits of the early 1930s found themselves unable to catagorise it, or bracket it alongside anything else. The initials by which the car was known were not quite

editorial mentions with mysterious advertisements urging

so new, however, and were quite familair to the keener

the reader to “Wait! The S.S. is Coming ...”’. So when the S.S.1 emerged into the public eye on the

members of the motorcycling fraternity as George Brough had used S.S. (suffixed by such as ‘‘80,”’ ‘“90”’ and 100”) as a model name for his superb two-wheeled machines. Brough Superior owner William Lyons obviously decided that “S.S.” would suit his purposes too, especially as the name met the approval of Maudslay and Black of the Standard Motor Company. Although this approval was not gained without “long argument’, recalled Sir William, ‘“‘which resulted from my determination to establish a marque of our own’’. The meaning of the letters was conveniently left open. ‘““There was much speculation as to whether S.S. stood for Standard Swallow or Swallow Special — it was never resolved’, said Sir William. The S.S.1 was a medium-sized coupe with a major part of its proportions given over to an extremely long bonnet, which began behind a stylish radiator grille set

occasion of the 1931 Motor Show at Olympia in October, it was with a confident air and without embarrassment,

despite an appearance that was truly avant-garde. Perhaps the only unfortunate aspect of that otherwise triumphant

launch was that the organisers of the Show, showing a distinct lack of appreciation and foresight, insisted that

the new car be relegated to Swallow’s old position in the section of the Show, instead of enjoying a

coachwork

stand in the Manufacturer’s Hall as was its right as truly a new make.

In a show where originality of design and execution was notably absent from the offerings of the ‘big names’, the S.S.1 stood out.

It wasn’t simply a case of instant

success and acclaim, though on the whole the car received very enthusiastic reviews, and there were certainly no novelties in its mechanical specification or method of

well back between the front wheels and ended in a small,

7)

,

-

low, passenger compartment with two doors. The multi-

works. As for power plant, transmission and suspension,

louvred side panels of the bonnet emphasised its length,

the Standard Motor Company became the natural choice as supplier - not only had Lyons already built up a good relationship with Standard’s chairman and managing director R.W. Maudslay and general manager John Black (who had come from Hillman in 1929, after marrying one of the many Hillman daughters), but also the notably smooth and reliable Standard 16 engine had all the characteristics which would suit the intended new car very well. It was soon arranged that Standard would accept the

and so did the absence of running-boards between the helmet-type wings. The coupe top had been given a ‘leather-grained’ finish, this material extending to the separate luggage compartment which sat behind the bodyshell proper. Dummy chromium hood-irons decorated the rear side-quarters behind the doors, but as

if to make up for the lack of a true folding head, a slidingroof was fitted as standard - this was specially made for Swallow by Pytchleys to present an unbroken roof-line when closed, the normal sliding-roofs of the period moving back above the roofline. One cannot say that Swallow — or Lyons — was the very first with this type of approach to bonnet/passenger-space apportionment; a long bonnet combined with low build had been showing signs of becoming a trend amongst more sporting vehicles for the previous couple of years, with examples of the style being mounted on proprietory chassis by a few continental coachbuilders, and even by

established British concerns as Gurney Nutting and Mulliner on such as 6.5-litre Bentleys (complete with fabric roofs). But these were generally expensive ‘one-offs’, and in any case, Lyons took the theme much

further - and

brought it to the semi-mass production market at a price many could afford. In a critical review of the 1931 Show,

the S.S.1 was about the only vehicle in the bodywork section at Olympia which that most analytical of journals,

Automobile Engineer, felt able to single out for comment on its appearance - “‘a very attractive car that is, if anything,

in advance ofthe times ...”” It was a brave step to break new ground when large sections of the motor industry, particularly coachbuilding concerns, were feeling the economic pinch and pulling in

new chassis frame from Rubery Owen, fit it with engine, transmission and axles, and deliver it to Holbrook Lane

as a running unit all ready to take its new bodyshell. Thus Swallow were relieved of having to put in any new machinery, and could merely continue their existing bodybuilding activities - but with the big difference that now, they could boast of using a chassis designed and assembled exclusively for them. The new chassis frame was ‘U’ shaped in section, and

all its main features were directed towards achieving the lowest body-line possible. From the front dumb-irons backwards, the side members ran parallel until they reached a cross-member under the radiator, where they

tapered outwards for about a foot, then ran parallel again right to the rear of the car. Where the scuttle was mounted, the frame dropped, to continue at this level under the passenger compartment, before running up and over the rear axle. Cross-members helped to provide torsional rigidity, assisted at the front by a transverse steel plate on which the front of the engine was mounted on two rubber buffers, but no ‘X’ bracing was incorporated. The long, flat nine-leaf road springs were anchored onto the outside of the frame both front and rear, rather than

their horns - “‘It is not to be wondered at, that in difficult times such as these, body builders have hesitated to make

beneath it, again to achieve the low look. Damping was by

alterations that might have a doubtful effect on sales” quoth Automobile Engineer in understanding tones. Indeed, time would tell that the coachbuilders’ trade was a dying

Standard axles were fitted with Rudge Whitworth splined hubs and 18-inch diameter wire wheels. Steering used the Marles-Weller cam and lever type box with Standard components linking the wheels, and the steering column was given a substantial rake which resulted in an almost vertical position for the steering wheel.

one, which maybe is one reason why Lyons and Walmsley staked so much on a single, innovatory move in October POSiE However, it would'be wrong to suppose that this was a major reason for the appearance of the S.S.1, which was

born chiefly of William Lyons’ increasing frustration through having to design his bodies to fit other people’s idea of a chassis.

In particular, it was very difficult to

achieve the fashionable long, low look using chassis produced by most car makers of the period. Through the position of their engines and the mounting of their suspension,

themselves

these

proprietory

chassis

to the ‘sit-up-and-beg’

really only lent

style of bodywork

which, despite Lyons’ flair for curves and colour, were all

too similar to the contemporary staid family saloons. The only answer was a specially designed chassis frame,

and during 1930 this was put in hand at the Rubery Owen 30

Luvax

hydraulic

lever-arm

shock

absorbers,

and

the

Statistically, Lyons had certainly achieved what he had

set out to do - compared with the original Standard 16 saloon,

the S.S.1

coupe

was

13-inches

lower

top

to

bottom, the floor 5-inches lower, the track 1-inch wider,

and the wheelbase 3-inches longer at 9-feet 4-inches. The heart of the car was Standard’s 2054cc six-cylinder engine, which was positioned no less than 7-inches back

in the chassis frame compared to the Standard Ensign from which

it came;

this was more

for looks than for

weight distribution, as it allowed the (lower) radiator to be set well back behind the wheels yet still result in an exceptional length of bonnet. The Standard six-cylinder engine had already accrued a good reputation for reliability, and in some respects was

William Lyons’ first car — the original $.S.1 Coupe; long and low despite the rather high cockpit. Hood-irons were dummy of course, and the side windows had a draught-preventer included at the top. Radiator shell carried a plated cast ‘‘S.S.”” motifon top. This rare survivor was totally rebuilt by its Australian owner Ivan Stevens. Head and trunk were finished in leather-grain material, and the lid of the trunk (secured by three catches) hinged rearwards to reveal luggage space and the tools carried in the lid itself. Aware of the limited rear-seat room, Henlys’ later offered a dicky-seat conversion which utilised the trunk; it also seems that they helped Lyons to arrive at the $.S.I concept itself, through their market knowledge. Photo: Autocar

—" quite sophisticated

in its specification - the crankshaft

the S.S. than the usual 5.11 ratio fitted to most Standard

with its seven-main bearings of 2-inches diameter was

16s.

both stiff and robust, and dynamically and _ statically;

Brakes too were from the Standard, of Bendix-Perrot manufacture with encased cables and a mechanical ‘duoservo’ action, so that mechanically, the car was easily

left the factory balanced pistons were of course

aluminium, and the rods were of duralumin whose light reciprocating weight gave scope for quite high revs for a unit ofthis size.

Unfortunately though, the engine’s breathing arrangements let it down sadly; mixture was initially supplied by

a single Solex carburettor on the offside of the engine block, with an abbreviated manifold feeding a tract which passed between cylinders three and four inside the block,

leading to a gallery on the nearside of the engine and thence to the (side) valves .... hardly an efficient method

ofdistributing the mixture. Continuing Swallow policy, no changes were made to

serviced by any Standard agent. Onto this orthodox but carefully mechanical and structural basis was fitted bodywork which set the car completely else. The separate, helmet-type wings were

thought out Lyons’ unique apart from all made of steel,

and incorporated a centre rib; at the front, they were partially included in the main bodywork by a tastefully curved extension of the panel which ran under the bonnet sides, and at the rear, they were set into the cockpit rearquarters. The chrome-plated radiator shell attracted much admiration with its vertical slats surrounded by a

the engine in the cause of more power; in order to cope

moulding which ran up over the crown to end in a motif

with the lower bonnet line, however, it was necessary for

at the top, and

the fan to be removed from its usual position on an extension of the water-impellor spindle and be mounted lower down on a bracket set below the impellor, with the fan belt now extended to drive it via a new pulley. The fan blades were also decreased in size, and may have con-

headlights mounted on a curved tie-bar running between the wings. Sidelights were carried on the wings.

tributed

towards

maybe one adult sitting crosswise. In front, however, the

overheating. Power output was around 45bhp, and this could be increased to about 55bhp if the 20hp version was specified, of 2552cc and with the rather better bore and

pleated leather bench seat was quite roomy and theoretically could accommodate three abreast, the gear

to

the

original

S.S.1’s

stroke ratio of 73 x 101.6mm

tendency

(compared with the 16’s

65.5 x 101.6mm); though this larger engine doesn’t seem

it was

flanked

by plated Lucas

P.170

Today, we would term the S.S.1 a ‘2-plus-2’ - while there were rear seats, no-one pretended that they were

meant

for anything more

than carrying children

or

lever being the biggest deterrent to this arrangement. For two people, the S.S.1 was really quite roomy, the cockpit being wider than, for instance, the S.S. Jaguar saloon which was to come four or five years later; this was

to have been available - or at least not publicised - until

due to the fact that owing to the absence of running

January 1932. In either case, the engine drove the rear wheels through Standard’s four-speed gearbox, a single

boards, the floor could be extended outwards to a point almost in line with the outer face of the rear wheel. It was

dry-plate clutch and a spiral-bevel rear axle. The gearbox had reasonably close ratios, and in conformity with

possibly the low height of the car, at 4 ft 8 ins, which gave it a slightly constricting feel. In this context it is interesting to note that William Lyons’ original design for the S.S.1 featured an even lower roofline. This, although it would certainly have

current

sporting practice had been fitted with a cast-

aluminium

extension

in

place

of

the

pressed-steel

gearbox lid, which carried the selector rods to a short gearlever close to the driver’s hand. Final drive ratio was the higher 4.66:1 offered by Standard, more suitable for Standard’s trusty six-cylinder engine with its ‘silent third’ gearbox as used in the Standard 16. Only minor alterations were needed for its very successful installation in the S.S.I1.

given the car an

even sleeker appearance, might have effected the habitability of the car, and it has been said that when Lyons went into hospital prior to the announcement date, the roofline was quickly raised

without his knowledge. Thus the S.S.1 appeared with its rather upright passenger compartment, which Lyons disliked and used to refer to as a “‘conning tower’; almost certainly, William Walmsley was responsible for

this alteration - no-one else would have dared to meddle! Throughout the car, Swallow had maintained its usual high standard of trim and equipment. Wood facia and cappings set the pattern which was to be used in virtually

all subsequent S.S. and Jaguar cars, although the finish in the S.S.1 was not the walnut which was to become so typical in later years. On the S.S.1 these were not true veneers, but special cabinet makers’ finishes applied to plain boxwood, very common from around 1920 to 1940; “fiddle-back”” sycamore was one, “birds eye’ maple

By

A.G. Douglas Clease holds open the door ofa very early S.S.1 for the benefit of the The Autocar

cameraman. Seats were mounted virtually flat on the floor so you sat very low in the S.S.1; seat back

hinged forward to allow access to the dark confines of the rear. Note

well-fitting bonnet and body sections — S.S. worked to coachbuilders’ standards even if

durability wasn’t all that it might have been with these ‘first series’ SSIs:

another. Various patterns were to be offered on the Swallow range. The door panels were trimmed in a sunray pattern, the Auster safety glass windscreen could be opened, and of course fresh-air motoring was provided by the Pytchley sliding roof, the moving section disappearing underneath the rear part of the roof when opened.

Lucas

electric windscreen

wipers, rear window

blind, and roof light switch were all at the control ofthe driver, who faced a comprehensive dash panel carrying an 80mph Watford speedometer, electric fuel gauge, a large Empire clock, and water temperature gauge - but as yet, no tachometer. Home comforts such as strategically placed ashtrays and a mirror and powder compact for the ladies (in the

hinged lid of the glove compartment) were provided, and carpets and headlining were carefully chosen to match the exterior paintwork.

The Motor of January 26, 1932, went

into considerable detail in describing the latter:

“There is a particularly wide range of artistic colour schemes. For instance, the body and wheels may be painted Nile-blue, apple-green, carnation-red, buff, birch-grey or primrose with the head, trunk and wings in black. For those who desire a coloured head, the follow-

ing schemes are available: apple-green body and wheels, olive-green head, trunk and wings; carnation-red body and wheels, black head, trunk and wings; buff body and wheels, chocolate-brown head, front and wings.”

Swallow’s press-release and advertising illustration of the original $.$.1 — this is probably the car as Lyons really wished it to be, with a much lower cockpit (compare it with the photographs ofthe real thing).

i ee ee

ed

39

Quite a mouth-watering selection! These colours were further set off by the plated Wilmot-Breeden bumpers

was a reasonable 39ft. 6ins. The Bendix cable brakes were

(full length at the front), the imitation landau-arms, and

up to par, and “‘the

the bright fittings on the luggage trunk. The spare wheel

pedal action is progressive and does not demand much effort on the part of the driver to obtain an emergency

was, not unattractively, fixed to the rear of the trunk, with

pull up’’. This statement should be qualified however, by

the rear number-plate mounted on an extension underneath together with the single rear lamp. The success or otherwise of the overall effect was a matter of taste, but there was unanimity of opinion on one point — the amazing value for money the S.S.1 gave, at a mere £310 (or £320 with the larger engine). Yet the car bore comparison in many respects with vehicles costing twice or three times that amount.

stating that the Duo-servo

a

prevent the wheels grabbing or locking up altogether, especially in the wet. Whether or not The Motor was over-enthusiastic when describing the S.S.1’s performance characteristics, the

magazine was correct in summing-up exactly what it was that Lyons was offering the motorist:

that it is a car built for the connoisseur but is relatively

The Motor was first in print with a road test of the 16hp

low priced. All the attributes of sports models are incorporated in a refined manner, and this, coupled with

S.S.1 in its issue of January 26, 1932, and was rather lavish

a striking appearance,

in its praise for the car’s behaviour on the road, perhaps

motorists of modest means’.

of Swallow's

gave the brakes

“... the S.S.1 is a new type of automobile in the sense

The S.S.1 on the road

mindful budget:

action

‘piling-up’ action, which meant that on a heavy application it was necessary to feather the pedal in order to

not

inconsiderable

advertising

“At the wheel one is reminded very much of a racing car, for the very long and shapely bonnet suggests immense power and the lowness of build of the complete

car gives an instinctive feeling ofsecurity .... “The writer has an enclosed car equally as fast as the

S.S.1 in so far as maximum

speed and even acceleration are concerned, but on a winding course of about 40 miles the S.S.1 maintained an average several mph greater than the normal saloon’.

But while comparisons with a racing car might have been overdoing things a little (the correlation was much more convincing after the war when it was applied to a descendant of the S.S.1, the XK 120), nevertheless the car