Israel Has a Jewish Problem: Self-Determination as Self-Elimination 9780190680268, 0190680261

The long-standing debate about whether the State of Israel can be both Jewish and democratic raises important questions

519 77 2MB

English Pages 288 [251] Year 2019

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

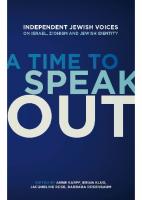

Cover

Israel Has a Jewish Problem

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

Acknowledgements

Notes on Terms

Introduction

1. Before the Law There Stands a Jew

2. On Goat Surveillance

3. The False Promises of Sovereignty

4. Self-Elimination

5. Is Israel a Christian State?

6. The Jewish Question Again

Bibliography

Index

Citation preview

Israel Has a Jewish Problem

Israel Has a Jewish Problem Self-Determination as Self-Elimination J OYC E DA L SH E I M

1

3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalsheim, Joyce, 1961-author. Title: Israel has a Jewish problem : self-determination as self-elimination / Joyce Dalsheim. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2019017903| ISBN 9780190680251 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190680268 (updf) | ISBN 9780190680275 (epub) | ISBN 9780190068943 (online) Subjects: LCSH: Jews—Israel—Identity. | Jewish nationalism. | Self-determination, National—Israel. | Jews—Israel—Politics and government. | National characteristics, Israeli. Classification: LCC DS143 .D25 2019 | DDC 956.9405—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017903 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

To the memory of my father, Stephen Dalsheim, a righteous man in his time, who taught me so much about what it means to be a mensch. I’m still trying.

Contents Acknowledgements Notes on Terms

Introduction

ix xiii

1

1. Before the Law There Stands a Jew

19

2. On Goat Surveillance

42

3. The False Promises of Sovereignty

61

4. Self-Elimination

90

5. Is Israel a Christian State?

130

6. The Jewish Question Again

161

Bibliography Index

197 215

Acknowledgements The Trees For we are like tree trunks in the snow. In appearance they lie sleekly and a little push should be enough to set them rolling. No, it can’t be done, for they are firmly wedded to the ground. But see, even that is only appearance. —Franz Kafka (1971: 382)

This is a book about Israel. But it isn’t. It is a book about what nationalism does, how it limits the possible ways of being because it needs a “people” who are sovereign. More than that, it needs its population to be legible, relatively easy to put to work and tax and conscript into the armed forces. So while there is room for certain kinds of differences, the state also requires a fundamental homogeneity among its population. James Scott (2017) would likely explain this as a form of domestication, like the domestication of grains and animals, or of forests and trees. This is a kind of self-domestication, a limiting of general ways of being. But the limitations—like tree trunks in the snow—are not immediately obvious. It takes some digging, both historically and theoretically, to figure out what’s going on. Books, of course, are like that as well. Their many surfaces, smooth and sleek, hide multitudes of encounters, connections, and dependencies with people whose names may never appear in the stories they tell. This book deals with troublesome modern categories like “nation” and “religion” that may seem arbitrary but come to be taken for granted. They, like the roots beneath the soil and snow, work in ways that may confound us. Many people

x Acknowledgements have helped me along the way to uncover the roots of an understanding of how political self-determination also involves forms of self-elimination. It’s been a difficult process, because of the complexity of the issues and the counter-intuitive nature of the analysis, and because the topic itself remains politically charged. So it is hard to get people to see what’s going on under the blanket of beautiful white snow. Some people agreed with the ideas I share here, and many disagreed, but all made me think. For that I am grateful. I would like to thank my editor, Cynthia Read, the wonderful anonymous reviewers who provided such insightful comments, and Katherine Ulrich for her meticulous and thoughtful copyediting. For providing the time and space in which to think and write I am grateful to my Chair, Dale Smith, and to the Luce/ACLS Fellowship in Religion, Journalism, and International Affairs, and to the Buffet Institute for Global Affairs at Northwestern University where Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Brannon Ingram hosted me. Thanks are due to Jean Clipperton for making me feel welcome and to Ben Schontal for being a great office mate. A special thanks to the Deering Library at Northwestern and its librarians, as well as to the wonderful librarians at UNC Charlotte’s Atkins Library. Many thanks to Sean, Sol, Sofia, Cecelia, Nora, and Gabriela, for providing a home away from home. For providing a forum in which to present the material and get feedback, I would like to thank Rebecca Bryant for the conference on sovereignty she organized in Cyprus where I presented a very early version of some of this work. I am grateful to Jonathan Boyarin for many wonderful conversations and to the Department of Anthropology at Cornell University for sponsoring my talk there. I also am grateful to all the faculty and students at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame who shared their thoughts during my presentation. Special thanks to Asher Kaufman for his detailed comments on an early draft of one of the chapters. Thanks to Danny Postel and all the

Acknowledgements xi scholars who engaged with my work at Northwestern. Many thanks to Rebecca Bryant, David Henig, and all the wonderful colleagues in Utrecht who provided feedback. For arranging a forum to present my work in Amsterdam and for her insightful comments, I would like to thank Yolande Jansen. For support and encouragement along the way—whether or not they liked my ideas—I would like to thank Gil Anidjar, Zvi Bekerman, Sam Brody, Peggy Cidor, Hillel Cohen, Assaf Harel, Martin Land, Abe Rubin, Amalia Sa’ar, Ben Schonthal, Gershon Shafir, Jackie Smith, Rebecca Stein, and Lorenzo Veracini. In particular, I am grateful to Gregory Starrett for always listening, reading, and pushing me to think further, to follow my instincts and stand firmly behind my ideas. To all those who raised challenging questions—like Jackie Feldman, who could ask a single question that would occupy me for months—thank you. And, to all those who disagreed with the arguments presented here, I appreciate those challenges, which ultimately made the book stronger, I think, I hope. This book would not have been possible without all the people who remain unnamed, my interlocutors in the field who gave generously of their time, welcomed me into their homes, and shared their thoughts with me. Finally, I would like to thank Rafi for his endless support and patience, and Edan and Ziev for believing in me. And, of course, I am forever grateful to Ursula, for long walks and constant companionship.

Notes on Terms Israeli Ways of Being Jewish Israeli Jews are often thought of in terms of a number of distinct categories. What those categories are, precisely, depends on whom you ask. We could, for example, begin with the distinction between religious (dati) and secular (hiloni). Each of these two groups might then further be categorized by the type of religious observance, or by ethnic origin, or by the political positions that are thought to characterize them. Of course, all of these categorical determinations are overstated. No group is ever homogenous, and each contains all sorts of differences. And no group is ever static; they are all always changing, and they often overlap. In addition, distinctions that might once have been typical can shift and change over time, making what seem like distinct groups more similar. For these reasons, any list of the ways of being Jewish in Israel or elsewhere will at once seem obvious and reasonable and helpful, but at the same time would in reality be misleading, inadequate, and already outdated as soon as it is written. In many ways these “groups” are best understood as locations of political, theological, and cultural contestation. Any way of constructing such categories, in other words, seems arbitrary. But although arbitrary, they are the distinctions through which social and political groups are constituted. They define inclusions and exclusions, but may be misleading both for those involved in these contestations, and for analysts, scholars, and readers who seek to make sense of them from different points of perspective.

xiv Notes on Terms That having been said, some readers may think it helpful to have a general sense of what is meant here by terms like “hilonim” or “Haredim” or “national-religious.” For those unfamiliar with the social-religious-political scene in Israel, I offer the following as a place to begin to think about Israeli Jewishness. Secular (Hiloni, pl. Hilonim) The majority of Israeli Jews self- identify as “secular.” However, according to recent polls, 60 percent of the secular also say they believe in God, and similarly significant percentages observe particular religious practices. “Secular” might describe Israelis who observe fewer religious practices than more observant Jews. The secular are those for whom religion or religious practice does not define their Jewishness. Of course, within both the religious and the secular communities, there are debates about what the term “secular” means in the first place, and what it has to do with one’s sense of identity or with one’s cultural practices, or one’s sense of Israeliness. “Hiloni” can be a term that people apply to themselves, but which they might also find offensive under some conditions. It might be hurled as an accusation by those who consider themselves “religious,” with the connotation that hilonim are ignorant of Jewishness, or that they are lacking in ethics and only interested in material possessions and pleasures. Religious (Dati, pl. Dati’im, or Dosim, from Yiddish, which is generally used by the non-religious in derogatory ways) The term “religious” is mostly used to refer to anyone who would not identify as hiloni. That, of course, includes a lot of different kinds of people! It includes religious Zionists, who are often called “national- religious.” Out of the religious Zionist population emerged an anti-Zionist strain rebelling against their parents’ generation for not resisting the state. Sometimes called the “hilltop youth,” they don’t think that the state always works in the best interests of the Jewish people, and so work on their own to colonize “illegally” in the Israeli-occupied territories of the West Bank. Thus, the term “religiously motivated settlers” (Dalsheim 2011) might be a more accurate description. But the term “religious” also might refer to

Notes on Terms xv the Orthodox, the ultra-Orthodox, and the modern Orthodox, not to mention the very minor strains of Reform and Conservative Jews, traditions imported from Germany and the United States, but not recognized by the Israeli state or its Rabbinate. And, among the Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox are various theologies and practices as well as political affiliations. The term religious can also include the “traditional” Jews discussed below. Traditional (Masorati, pl. Masoratiim) is a term generally used in reference to Jews from the Middle East and North Africa (Mizrahim) who keep traditional Jewish practices, but whose observance of Halakha is considered more flexible than other observant Jews. What unites Moroccan Jews and Iranian Jews—not to mention those from Azerbaijan or Iraq or Egypt or Yemen—is simply that they are not of European origin. But this term doesn’t cover Ethiopians. They’re just “Ethiopians.” Obviously what we’re talking about here is different from what we generally think of as “religious” identity, because it has to do with “nationality” or “national origin” or language or “ethnicity” or skin tone or racialized categories rather than “religiousness.” Mizrahim can be proud atheists, as are/were many Jewish immigrants from Iraq, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they get called “hilonim,” or secularists. That term is largely reserved for Ashkenazim, Jews of European origin. On the other hand, so many people are intermarried anyway, that who gets called what by whom for what purpose is, in technical social science terms, “highly contextual.” Haredi (pl. Haredim) is generally translated as ultra-Orthodox. Ultra? What does that mean, anyway? As Martin Land once said to me, “What, if the commandment is Thou Shalt Not Kill, so they ultra-don’t kill?” The term only makes sense if one thinks of Jewishness as some kind of continuum in which some people are not very Jewish and others are extremely Jewish. But such an idea raises all sorts of problems. Those referred to as ultra-Orthodox do not use that term to describe themselves and might even find that term offensive. While the word “Haredi” is broadly used to refer to the very

xvi Notes on Terms strictly orthodox, it includes a range of theologies, and followers of different rabbinic leaders, who are associated with particular Jewish communities in different parts of the world. The term Haredi can be used as an adjective or a noun. In general, the term refers to those Jews who strictly follow Halakha. They aspire to absolute reverence for the Torah, including both the Written and Oral Law, as the central and determining factor in all aspects of life. Consequently, respect and status are often accorded in proportion to the greatness of one’s Torah scholarship, and leadership is ideally linked to learnedness. Foundationally, the Haredim are not supporters of political Zionism. Nonetheless, several Haredi groups have their own political parties in Israel. These groups are sometimes distinguished by ethnic origin. So, for example, the political party Sephardi Torah Guardians (Shas) represents observant Sephardi Jews (those of Spanish or Portuguese ancestry) and those from the Middle East and North Africa. It is distinguished from other Haredi political parties that represent Ashkenazi Jews (those of Western, Central, or Eastern European ancestry). Shas has been analyzed as gaining wide support among Mizrahim, regardless of their levels of observance, because it provided social welfare, including childcare. Thus, socioeconomic issues are also interspersed with religion and ethnicity. But these parties sometimes split from within for all sorts of reasons. Recently, Adina Bar Shalom, the daughter of the former chief rabbi of Shas, Ovadia Yosef, started her own party and she has supported other religious women political candidates from other streams of Judaism. Thus, gender also plays a role. In addition, Hasidic Jews (Hasidim) are usually distinguished from other Haredim. Hasidic communities were generally formed around a charismatic rabbinic leader and came to be known by the name of the town in Eastern Europe (e.g., the Gur Hasidim, the Lubavitch, or the Belz) in which they originated. In Israel today, there are all kinds of combinations of theology in which Hasidic thought combines with national-religious thought, or Haredi ideas combine with the ideas and practices of religiously motivated settlers. In the occupied

Notes on Terms xvii West Bank today, one can find yeshivas among religiously motivated settlers that take their inspiration from a particular Hasidic rabbinical tradition, or settlers whose theology has come to more closely resemble Haredi anti-Zionist ideas. And, of course, among the Haredim are those who are more inclined toward Zionism and service to the state. But, according to The Jewish People Policy Institute, Haredim in Israel are best defined as “the population whose males generally do not serve in the Israeli military, because they receive a Torah study deferment. About half of the male Haredi population works. The other portion studies Torah full time.” They are defined here, in other words, in terms of their relationship to the state, or to Zionist ideologies of duty and responsibility.

Other Terms/Translations Aliyah: Literally, to “go up.” Refers to Jewish immigration to Israel. It can be used as a verb when a person is said to “make aliya.” But it also refers to specific waves of Jewish immigration to Israel/ Palestine (e.g., the First Aliyah was a major wave of Zionist immigration to Palestine that occurred between 1882 and1903.) Halakha: Halakha can be translated in reference to its linguistic root in the word “to go,” signifying a path or direction, and designates the proper path or guide to life actions and decisions. The term Halakha sometimes refers to a particular law or ruling or to the entire system of law. It includes biblical commandments as well as interpretations of the great sages of rabbinical Judaism. Haskalah: Generally refers to an ideology of modernization in 19th-century Europe. It is sometimes called the Jewish Enlightenment and is traced to the thinking of Moses Mendelsohn. Its central ideals included ways of combining traditional study with secular subjects that would help integrate Jews in European societies. Ketubah: Marriage contract. Mikveh: Ritual bath.

xviii Notes on Terms Mitzvah (pl. mitzvot, mitzvoth): The term used in reference to biblical or religious commandments. There are said to be 613 commandments. Although this number is disputed, its origin is traced to a 3rd-century-ce rabbi who explained that the 613 commandments included 365 negative commands (do not), which correspond to the number of solar days in a year, and 248 positive commands, corresponding to the number of human bones covered with flesh. This emphasizes that one should fulfill the mitzvot every day and with every bone in one’s body. Indeed, among observant Jews, mitzvot are part of everyday life, for example, eating only kosher food and resting on the seventh day (Shabbat). Keeping the mitzvot is a fundamental good; it involves doing the good that God has commanded of His people. As such, the mitzvot are not only good for the person who keeps them, but for the world. In some interpretations, living according to the mitzvot contributes to repairing the world and preparing for the messianic age, a time when it will be possible to perform all mitzvot in their ideal context. In order to live according to the mitzvot, one must study and learn them. Thus understanding and action, study and performance are intimately intertwined. The term mitzvah is used in common parlance to mean a good deed. Torah: The physical Torah scroll, handwritten on parchment and prepared by a Torah scribe, that is opened and read aloud in synagogue. The content of the Torah refers to the five books of Moses, but may also include other Jewish sacred literature.

Israel Has a Jewish Problem

Introduction “Western thought works by thesis, antithesis, synthesis, while Judaism goes thesis, antithesis, antithesis, antithesis . . .” —The Rabbi, in The Rabbi’s Cat (Sfar 2005: 25)

John Emmerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, the 1st Baron Acton, lived from 1834 until 1902. He was perhaps most famous for the idea that “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” one of those quotes we easily recognize, but can’t quite place. Acton’s book, Essays on Freedom and Power, appeared posthumously in 1948. I came across that book at the Hannah Arendt Library at Bard College, where I found Arendt’s underlining in her paperback copy. It was the 1955 edition, its pages yellowing with age. More than a century after his death, I found myself intrigued by Acton’s words and captivated by Arendt’s underlining and her small, precise handwritten notes in the margins. It was as though, more than four decades after her death, I was thinking with the brilliant woman herself. Acton was writing about political systems and the history of freedom, beginning in antiquity. In a section about the position of citizens within the state, Arendt underlined a sentence that said, “The passengers existed for the sake of the ship.” That sentence struck me as encapsulating the essence of nationalist projects and the production of national communities, which I had been Israel Has a Jewish Problem: Self-Determination as Self- Elimination. Joyce Dalsheim, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190680251.001.0001

2 Israel Has a Jewish Problem studying for some time.1 “That’s the whole story,” I thought to myself—“nationalism in a nutshell.” The passengers are there so that the ship can make its voyage, not the other way around. But the passengers can’t see things that way. That would ruin everything. They (we) have to purchase or somehow acquire their tickets and experience that purchase as their decision. It matters little whether those tickets were acquired with the ease of wealth and privilege or through enormous struggle; the passengers must experience the voyage as their choice and for their benefit. All such metaphors involve a level of oversimplification. We might continue the metaphor and think about whether everyone on such a ship counts as a “passenger,” especially people who are captives on that ship, people who did not choose to be there, or who want to mutiny or to escape. Issues such as these will be explored later in the book. Nonetheless this idea of the ship, I thought to myself, is an apt metaphor for the case of the modern state of Israel. Its passengers, “the people” of the nation, enable state projects, and despite ideas about social contracts and popular sovereignty, those projects seem to have a life of their own. Samuli Schielke (2018) recently suggested that scholars sometimes treat abstract concepts the way animists treat non-humans, inanimate objects, or processes of nature. We attribute responsibility and intentionality to them. My theorizing in this book is surely implicated in that observation. I have been engaging with and thinking about Israel/Palestine for nearly four decades, and count myself as among those scholars who have found the theoretical framework of settler colonialism most productive for thinking about this case.2 Much to the chagrin 1 For example, see Dalsheim (2003; 2007) on how conflict over the content of national history does not weaken national identity, as one might expect. Instead it strengthens a sense of national pride. See Dalsheim (2004) for a comparison of settler nationalism in Australia and Israel and how representing the past works to produce social and political identities for national projects. 2 Maxime Rodinson (1973) was probably the first scholar to write about Israel as a “colonial-settler state,” a designation that has become increasingly popular among critical scholars and political activists who seek to decolonize Palestine. Later, critical Israeli sociologists and historians began to analyze Israel in terms of colonialism. Baruch

Introduction 3 of many Israelis I know, I continue to see its value. But I am also convinced that settler colonial theorizing requires some expansion and rethinking. Seeing social formations through a settler colonial frame provides clarity. Like any frame, it helps focus the eye on some things while also excluding other things from the picture. While we should take care not to ignore important details, such framing can be very helpful. It allows us to see patterns and recognize processes that repeat in other contexts. Unlike other forms of colonialism, “settler-colonization is at base a winner-take-all project whose dominant feature is not exploitation but replacement. The logic of this project, a sustained institutional tendency to eliminate the Indigenous population, informs a range of historical practices that might otherwise appear distinct—invasion is a structure not an event” (Wolfe 1999: 163). Contemplating that last, powerful phrase and its implications, it became clear to me that Wolfe was right. Settler colonialism is indeed a structure, and one that is discernable in the United States, Australia, Canada, and elsewhere, but it is also a process (Dalsheim 2004, 2005, 2011b) in much the same way that capitalism is a structure and also a process. Settler colonialism may shift and readjust its route, but the course remains set, unless somehow the entire ship is dismantled. I have written about the ways that settler colonialism can fool us by separating itself from itself through social, cultural, religious, and political categories that appear as binary oppositions (Dalsheim 2011b). In the case of Israel one of the ways this happens is when the term “settlers” is applied only to those who are ideologically driven to expand the size of the state and who live in Israeli

Kimmerling called Israel an “immigrant-settler” state. Gershon Shafir (1989b) analyzed Israel as a “pure settlement” colony, where state policies have been based on attempts to control the land and labor markets. Shafir wrote that “what is unique about Israeli society emerged precisely in response to the conflict between the Jewish immigrant-settlers and the Palestinian Arab inhabitants of the land” (1989b: 6). See Uri Ram (1995) for more details on the history of Israeli sociology and the emergence of this school of thought.

4 Israel Has a Jewish Problem Occupied Palestinian Territories. The term settlers is juxtaposed to other Jewish Israeli citizens, some of whom might oppose expanding settlement. It marks a part of the population as settlers rather than understanding the whole of the Zionist project as a settler colonial enterprise. Here, I continue thinking about those categories and oppositions in order to untangle some of the ways that the Israeli nation-state produces the passengers for the sake of its ship, whose primary goal is the establishment and maintenance of a self-proclaimed Jewish state in the space of Israel/Palestine. Scholars like Rachel Busbridge (2017) have been critical of the settler colonial “turn” in Israel/Palestine studies because the term itself can offend people and therefore close down debate or limit certain kinds of political processes. Much in the same way as the word “apartheid” in Israel or the word “socialism” in the United States have been decried as divisive, settler colonialism carries too much weight, too much meaning. It evokes too much affect, which only causes people to get angry and stop listening. If you are offended, dear reader, I ask that you bear with me for just a little longer. It’s about to get worse. I do not disagree with Busbridge’s assessment, but suggesting that a form of theoretical analysis is not palatable for particular kinds of political activism is not the same as demonstrating that the analysis is wrong. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, abandoning theory for praxis has the potential to subvert the goals of those who do so (Dalsheim 2013c, 2014). My purpose here is not to undermine the conceptual framework of settler colonialism, but to explore and expand parts of its analysis in order to gain additional insight into some of the processes I am calling Israel’s Jewish problem. One of the ways I am expanding on that conceptual framework is by putting it in conversation with a much earlier critique of Zionism that preceded settler colonial studies, but to which the latter rarely refers. Doing so is one way that I refuse the secular/ religious divide, which is not only a predominant way of understanding the issues I raise about Israel’s Jewish problem, but also

Introduction 5 works to keep (secular) scholars from thinking with (religious) sages. This separation, I think, is part of what Eduardo Viveiros de Castro meant when he wrote about “the vicious dichotomies of modernity” (2014: 49). Like Viveiros de Castro, I too am convinced that most important anthropological theory can be understood as versions of knowledge practices of the people we study, “indigenous practices of knowledge” (Viveiros de Castro 2014: 42). Comparing two forms of criticism that are rarely considered in concert, I have been intrigued by an interesting convergence around the question of assimilation. Writing about Australia, Patrick Wolfe asserted that “assimilation completes the project of elimination” of the Indigenous population (1999: 176). When he wrote about Israel/Palestine, Wolfe made very clear that the modern state of Israel is a settler colonial formation established by Jews who primarily came from Europe, and that Palestinian Arabs were the Indigenous at whom the project of elimination was aimed. He was not wrong. Given the ongoing suffering of the Palestinian population in the space of Israel/ Palestine—the constant precarity and endless forms of spacio-cide (Hanafi 2012) aimed at them—it might seem frivolous or irresponsible to shift the focus toward those positioned as settlers in the settler colonial structure. Patrick Wolfe and other scholars of settler colonialism have written about settler ideologies, erasures of the past, and the production of national narratives that glorify the settler project and make heroes of its protagonists. They have primarily focused on how settler imaginings work together with dispossession of native lands, and Wolfe in particular has shown how dispossession can also work through assimilation. But it seems to me that the processes of assimilation/elimination are even broader than Wolfe has suggested. This book is concerned with processes of assimilation aimed at producing Jews as “the nation.” It looks at how Jewishness is constrained in the Israeli context through myriad struggles over meanings and practices of being Jewish. The book adds to the

6 Israel Has a Jewish Problem scholarship on nationalism by putting it in conversation with ideas generated through settler colonial scholarship and by continuing the analyses of those scholars who place both nationalism and colonialism within broader analyses of modernity. It continues the critique of modernity/Enlightenment by refusing some of the categories through which modernity seeks to describe itself, primarily the binary distinction between religion and the secular. In this way, it adds to a growing interdisciplinary literature that closely examines what secularism means and how it works.3 At the same time, it uses fieldwork data—ideas expressed by people directly involved—to bring forward particular Jewish concerns about the dangers of assimilation associated with Zionist nationalism and sovereignty in a self-proclaimed Jewish state. In order to think more productively about both assimilation and secularism, the book enters a conversation with a group of scholars who are primarily concerned with preserving Judaism and protecting Jewish identity from the dangers of Zionism. Drawing heavily from the perspectives of traditional Orthodox Judaism, Yaacov Rabkin (2016), for example, insists that the modern state of Israel is not a Jewish state. He recounts the history of Jewish opposition to Zionism, often quoting rabbinical sources and explaining how identification with the modern state tends to replace a “value system typical of Judaism” with nationalist ideals (2016: 50). Yaacov Yadgar (2011) employs what he calls a “traditionist” (masorti) Jewish perspective to suggest that “secular” Israeli Jews (hilonim) have no meaningful Jewish identity except that which is imparted to them by the state. While they complain about religious impositions on their lives, Yadgar (2017) argues that these statist Jews benefit from those impositions. It is what identifies them as Jews in Israel and allows them the privileged position of sovereign 3 Examples of this interdisciplinary literature include the work of anthropologists like Talal Asad and Webb Keane, political scientists William Connolly and Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, and philosopher Charles Taylor. Chapter 1 deals with the extensive literature on the secular and secularism in much greater detail.

Introduction 7 citizens in an ethno-national state. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin has been consistently critical of Zionist ideology and its notion that the establishment of the state of Israel represents a negation of Jewish exile. Raz-Krakotzkin (1994) instead exposes Zionism as the negation of traditional Jewish understandings of the concepts of exile and redemption. These concepts have been re-narrated through Zionist discourse to produce a unified national identity that also erases the rich historicity of diverse forms of Jewish life. In particular, by aligning itself with the West, Zionism identified itself in opposition to the East, marginalizing the rich cultures of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa so that being Jewish primarily came to mean not being Arab.4 Raz-Krakotzkin also suggests that Jews of the Middle East and North Africa (Mizrahim) might be able to provide an alternative to this “crisis of Zionism” (2011: 73). Such critiques of Zionist nationalism that draw on traditional (or religious) values resonate with similar critiques of nationalism in other places, especially with the work of Ashis Nandy (e.g., 1995, 1988). These scholars are all interested in preserving collective identity rather than deconstructing it, as much social science might recommend. Like Hannah Arendt, who came to these questions not from traditional Judaism, but as a secular Jew who had herself experienced exile, these critics suggest there may yet be a way to preserve the Jewish nation without Zionist nationalism.5 Unlike these historians and political scientists, as an anthropologist I do not see my role as determining what is and what is not Jewish, nor as providing alternative models or content to Jewish or Israeli identity. Instead I present an argument based on years of ethnographic engagement that considers the multiple and conflicting 4 There is a growing literature on the positionality of Mizrahim, too extensive to cite in detail here. For some of the foundational texts dealing with the question of the Arab-Jew see Ella Shohat (1988, 2017), Gil Anidjar (2003), and Yehouda Shenhav (2006). 5 Raz-Krakotzkin (2011) is critical of Arendt’s Eurocentric Orientalism, but builds on her ideas in his work on bi-nationalism. See also Raz-Krakotzkin (1993) on being in exile as an ethical model of living. Daniel and Jonathan Boyarin (1993) have written about diaspora as a non-territorial and preferable way of maintaining Jewishness.

8 Israel Has a Jewish Problem ways in which sovereign citizens of Israel struggle to be Jewish there, and I offer a way of understanding what might otherwise seems like a bizarre situation. I build on Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin’s idea of how Zionism tends to narrow definitions of Jewishness. However, I am convinced that this narrowing is not only aimed at Jews of the Middle East and North Africa. Indeed, the processes of producing the ethnos for the ethno-national state affect all Jewish Israelis in one way or another. Such processes are not specific to the Jewish state. There are many cases in which state laws determine what will and will not count as a particular religion, “inventing and reinventing religious orthodoxy for a given community” (Sullivan et al. 2015: 7). For example, in the introduction to their book on the Politics of Religious Freedom, Sullivan and her colleagues discuss the case of Thailand. Historically, they explain, there were at least five different traditions of Buddhism in the place that is now Thailand. “At the end of the nineteenth century, in a modernizing move . . . the king decided to unify the sangha (the Buddhist monastic community). In deciding what counted as Buddhism . . . Buddhist teaching was repurposed” so that “the Thai state would have religion as the foundation of its national identity. This . . . resulted in, among other things, the repression of local Buddhisms” (2015: 7–8). The state of Israel is likewise engaged in defining what will count at Jewishness. However, scholars like Yadgar suggest that “the state” relies on a narrow Orthodox interpretation of Jewish religion to maintain a Jewish majority, which like the notion of state repression, implies a top- down model of imposition. My research suggests that the processes underway in Israel are actually much more complicated. This is, first of all, because “the state” is not so easily separable from “the people.” While a fictional reality of unified, centralized state power retains its hold on our imaginations, in fact state and civil society are deeply intertwined (Aretxaga 2003; Gramsci 1971). State power works through the myriad struggles over Jewishness in Israel. It requires that people believe in their capacity to influence what

Introduction 9 Jewishness will mean in their state and in their capacity to thereby influence its character.

Producing the Nation Modern political theory teaches us about social contracts, in which citizens give up certain rights to the state in return for its protections, so that the state can serve our needs. Modern nation- states, particularly those imagined as democratic, are meant to liberate citizens because they are understood to be ruled by “the people” and for “the people.” But thinking with Acton and Arendt’s underlining, we also see an inversion of this story. If people exist as “a people” for the state and its projects, then there is nothing particularly liberating about the formula of sovereign citizenship. And yet, so many nationalisms, especially anti-colonial or separatist movements, are premised precisely on a rhetoric, ideal, or belief in its liberating quality. Political Zionism, for example, promised collective self-determination.6 The Jewish people would take charge of their own future. They would return to their ancient homeland and revolt against British colonial rule. They would be a free people and would flourish in their own county. Liberation, however, is not the way in which most scholars have analyzed nationalism. When Eugen Weber (1976) wrote about the processes through which peasants were transformed into members of the French nation, he was concerned more with modernization than liberation. Ernest Gellner (1981) wrote about processes of modernization too. 6 Political Zionism is one variation of Zionism, and the one that ultimately became dominant in the establishment of the state of Israel. Like other movements, Zionism was (and maybe still is) a plural movement that included multiple debates and different ways of imagining Jewishness, community, and the future. On the variety of Zionist thinkers see Hertzberg (1959). On the different sorts of territorial visions related to different versions of Zionism see Shelef (2010). On post-Zionism see Nimni (2003) and Ram (2005).

10 Israel Has a Jewish Problem Gellner was convinced that nationalism was an inevitable corollary of modernizing societies. Both Weber and Gellner described how nationalism encourages cultural homogenization through adopting a single national language, standardized education, and other processes. Benedict Anderson (1983) expanded on the ways that specific modern innovations like the printing press enabled what he famously called the “imagined community” of nationalism. That sense of community as an extended family and that sense of belonging are part of the reason people experience emotional anguish for other members of their nation, and the reason that people are willing to fight and die for it.7 Nationalists themselves celebrate nationalism’s unifying powers. But another way of understanding national unity is to think not only of the people it brings together, and of those who are often brutally excluded, but also about what is lost to “the nation” itself in the process. The forces involved in producing national unity might be best understood as a form of assimilation. Eugen Weber understood this. The final section of his famous book, Peasants into Frenchmen, explains that regional languages and other elements of peasant culture “changed and assimilated” into a greater French culture (Weber 1976: 377–484). “What happened,” he wrote, “was akin to colonization” (Weber 1976: 486). “In France, as in Algeria, the destruction of . . . local or regional culture, was systemically pursued” (Weber 1976: 491). Weber was not quick to mourn this loss or destruction. He argued that “traditional culture was itself a mass of assimilations, the traditional life a series of adjustments to 7 Partha Chatterjee (1986), publishing about a decade after Weber, likewise argues that thinking about nationalism as the opposite of colonialism is a mistake, but for different reasons. Chatterjee is concerned with the false promises of freedom specifically in anti-colonial nationalism. He contends that nationalism allows many colonial patterns of thought to continue, but that they often go unrecognized. He writes about what he calls “the bi-level nature” of nationalist thought. On one level, it “appears to oppose the dominating implications of post-Enlightenment European thought,” but on another level, it “seems to accept that domination” (1986: 37). Like other scholars of subaltern studies, Chatterjee also argues that anti-colonial nationalism primarily benefits the middle class elites, which is another continuation of domination.

Introduction 11 physical circumstances” (Weber 1976: 492). “Change” he explained, “is always awkward, but the changes modernity brought were often emancipations, and were frequently recognized as such” (Weber 1976: 492). Assimilation to a national culture, then, might be destructive and tantamount to colonization, but this destruction was liberating; it was “good” for the people it changed, and they knew it. Scholars of post-colonialism, including those who study settler colonialism, however, are not likely to consider such processes as liberating. On the contrary, liberation entails de-colonization, including decolonization of the mind, which might be the polar opposite of assimilation.8

Yes, But Is It Good for the Jews? The question posed in this subheading will be recognizable to many in the Jewish community as a common way of evaluating events, decisions, and policies of all sorts. People also laugh about it. It’s an insider joke, a cliché, a kind of punch line. But when we think of nationalism, assimilation, colonization, and cultural destruction, this question also reveals an irony embedded in the categories through which we navigate modernity. If we take seriously the scholarship I just laid out, we are left with a rather complicated conundrum. National sovereignty, according to Eugen Weber, is at once liberating and colonizing—colonizing precisely those whom it presumes to liberate. It is a form of freedom that entails processes of cultural elimination through assimilation. Establishing the modern Jewish state was seen as an alternative to

8 Franz Fanon, in Black Skins, White Masks (1967), explored the psychology of colonialism, how it is internalized by the colonized from the point of view of the colonized subject. Ashis Nandy expanded on these ideas in his discussion of The Intimate Enemy (1983), where he writes about the idea of a dehumanized self and an objectified enemy, which he attributes to the psychological effects of colonization. Fanon’s ideas have also been taken up by Ngugi wa Thiong’o in Decolonising the Mind (1986).

12 Israel Has a Jewish Problem assimilation in other countries where assimilation would mean the destruction of Jewishness or of the Jewish people. And at the same time, political Zionism was (is) a movement that imagined cultural change as part of the process of liberation in much the same way as other nationalisms. But to think of such cultural changes as being akin to the forces of assimilation that Jews were (are) subjected to in Europe as positive and liberating should not only be surprising. One might consider it offensive, if not downright anti-Semitic, as it aims to eliminate particular ways of being Jewish. And yet, objections to Zionism raised by devout Jews have been precisely concerned with its anti-Jewish nature. So, is the modern state of Israel also anti- Semitic? Is it “good for the Jews”? What are “the Jews”? Political Zionism, like other modern nationalisms, was inspired by Enlightenment thought. That thought included ideals of progress and liberation not only through political self-determination, but also by gaining freedom from religious constraints— not freedom of religion, but freedom from religion. Religious freedom, of course, requires a definition of “religion,” a common term whose meaning we tend to take for granted.9 We think of people who pray or belong to different denominational groups, people who attend church or worship at temples as practicing or having a religion. We can name religious groups and think of people as being Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and so forth. But this taken-for- grantedness conceals the genealogy of the term religion and might prevent us from understanding what happens when we classify it as separate from other modern identity categories like nation, race, or ethnicity. I first began thinking systematically about how power can work through obvious categories and distinctions when I read Michel Foucault’s Archeology of Knowledge. Foucault warned against easily accepting apparent unities. In addition, he suggested that the appearance of disunity should also be a cause for skepticism (Foucault 9 See Sullivan et al., Politics of Religious Freedom (2015).

Introduction 13 1972: 22). Foucault is famous for interrogating categories like “madness” and “sanity.” But we might also think about “religion” as an identity marker that is meant to distinguish spiritual feelings, ritual practices, and philosophical positions from “demographic” characteristics, marking one element of identity as subject to choice or constraint in a way that others are not. Talking about “religion” as separate from other categories makes these elements of experience appear as a special part of the self that can be changed at will. In and through that change one could, at least theoretically, move from one social category to another. In fact, such a process of “conversion” was posited not only as a theoretical possibility, but as the moral core of a modern sense of political liberty: one could choose what to be in a way that one could not choose one’s ancestry, one’s gender, or one’s age. And if that was the case, then beyond the capacity to choose to alter these elements of experience and identity, there became a moral duty to treat them as always open to question, comparison, evaluation, and judgment. Individuals became responsible for their “religion” in a way perhaps parallel to the responsibility for personal assent to a mythical “social contract.”10 In the case of the modern state of Israel, the question of “Who are the Jews?” is both a religious question and foundational to nationalism, which means that nation and religion are at once separate and conflated. This kind of ambiguity makes even a Foucauldian analysis seem inadequate to the task. To put the problem as starkly as possible, we might say: In order to be free, Jews should gain self-determination as Jews (a national group). They could liberate themselves from political oppression and free themselves of religious constraint by claiming and enacting the right to national self-determination. In this way, they could be free as Jews (national identity) and stop being Jewish (religious identity). But since these two categories—religious and national—have been conflated in the 10 I am indebted to Gregory Starrett for this explication of the modern (Western) understanding of the category “religion.”

14 Israel Has a Jewish Problem figure of the Jew, such freedom is impossible. While people might reject attending synagogue or keeping the Sabbath, in order to be “the people” who have sovereignty in the self-proclaimed Jewish state, in one way or another they have to be Jewish and someone has to decide what that means. This case is instructive for the study of nationalisms more generally. It is also an ironic case and, I would argue, somehow self-defeating. The modern state of Israel can be understood as an ethno- national state, an anti-colonial nation-state, and a settler colonial state, all of which entail systems, processes, or projects that seem to demonstrate a kind of intentionality. Part of the purpose of this book is to continue thinking about the ways such projects work and how they can confuse us by appearing to be something else, and how everyday life inside such systems inundates us with details that are so complicated and encompassing that we fail to see the forest for the trees. To remain with Acton’s metaphor, such projects can keep us so busy and distracted that we might not realize that as modern citizens we are on a voyage, heading in a particular direction, and that we are not necessarily steering the ship. Indeed, it is important that we imagine ourselves capable of influencing the direction that we sail, whether or not any of us is ever actually at the helm.

The Kafkaesque Multiple, seemingly endless ironic and contradictory situations arise from the problematic categories of nation and religion in the modern state of Israel and the territories it occupies. Encountering such situations throughout my fieldwork gave me a distinct sense of the Kafkaesque. Much of Kafka’s writing is allegorical in ways that express a predicament similar to Acton’s passengers who exist for the sake of the ship. The Kafkaesque is steeped with senses of simultaneous motion and immobility.

Introduction 15 There’s a saying in modern Hebrew about people who rush around but never get anywhere: ful gaz b’neutral; the gas pedal is pressed to the floor, but the vehicle is not in gear. It can’t move. It’s a way that Israelis make fun of people they think are foolish, expending so much energy and yet never making any progress. Kafka might have said that ful gaz b’neutral applies to all of us.11 In any case, it seems to be how he experienced life. His writing often depicts some kind of maze in which his characters are trapped, while they never seem to fully comprehend the contours of that which entraps them. No matter which way we turn—and, as this book will illustrate, we do turn and twist and run and struggle—there are forces that constrain us. Kafka’s protagonists seem to endlessly find themselves in impossible situations. His work often illustrates a deep sense that there is no way around broader, seemingly senseless and oppressive systems. Kafka’s characters try to act, make mistakes, realize their mistake, and move in a different direction only to find their new approach is blocked too. Rebecca Schuman (2015) describes this as the double twist that characterizes the Kafkaesque. The Kafkaesque is unsettling. His stories often evoke a feeling of unease. The social world seems unpredictable if not unjust, and Kafka’s protagonists seem incapable of ever coming to understand its laws (see Constantine 2002: 22). His work has also been noted for evoking a sense of exile (see Bruce 2002:151–152), which seems poignant because Zionist nationalism suggests that the establishment of the Jewish state marks the end of exile, while scholars like Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin strongly refute that idea. Finally, if Kafka’s characters seem like captives, Kafka’s writing is also captivating in itself. It draws us in in much the same way that life’s daily struggles

11 Who might be included in that “us” is up to readers to decide. Kafka was, of course, a modern Western author whose work reflects on the predicaments of Western modernity. The theories of nationalism outlined here refer primarily to modern European forms of nationalism on which Israel modeled itself.

16 Israel Has a Jewish Problem keep us occupied: so busy that we can’t even stop to think about how that very busyness is itself a form of subjugation.12 The everyday struggles over Jewishness in Israel involve that kind of busyness and take place within commonly accepted dichotomies like left-wing versus right wing, religious versus secular, freedom versus constraint, liberal versus illiberal, and so forth. These dichotomies are the kinds of disunities that Foucault suggested should arouse our skepticism. The story of contemporary Israel tells of a people seeking freedom from oppressive regimes that marginalized, excluded, or tried to destroy them. And so, they ran in the other direction only to find themselves trapped again in a different variety of the same oppressive system. The nation-state appeared as a means of liberation and a means of ensuring survival for a persecuted people running for their lives from extreme nationalism in Europe. But some of the processes that helped produce the chauvinistic nationalisms of the 19th century also underpinned the establishment by the broader international community of the state of Israel itself, which is now often derided in the international community for being precisely what it was set up to be: an ethno- national state proposed as the solution to the acute problem of ethno-nationalism. And so, while this book focuses on problematic processes inside the Israeli nation-state, that focus cannot be understood without the broader historical context that continues to haunt us. These days it seems quite clear that we are not done with nationalism and its attending xenophobic violences. Indeed, it seems that racist and intolerant forms of nationalism are ever more common. Much of the scholarly critique of nationalism has focused on those it excludes, such as stateless people, refugees, and internal Others within a polity. Certainly national sovereignty seems preferable to such precariousness. Sovereign citizenship appears to be a position 12 See my article on deconstructing national myths (Dalsheim 2007) that explains how busyness works as a form of hegemony.

Introduction 17 of strength. And so we continue to criticize the dangers of popular sovereignty in the form of ethno-nationalism, while simultaneously recommending it as a means of achieving liberation.13 More of the Kafkaesque. I am not a literary scholar, nor an expert on Kafka. I claim no authority in understanding his work. But when I think of the struggles to be Jewish in Israel, Kafka’s work speaks to me. He made sense at the time he was writing and makes sense now. That “then and now” in itself is part of why his work is here. Like the frames available through social science, thinking with Kafka also allows us to see patterns and repetitions that might otherwise appear distinct, random, or disconnected. It provides a space in which to make unusual or unpopular comparisons, such as the central claim here that despite the promise of the term “self-determination,” popular sovereignty in the nation-state also necessarily entails self-elimination.14 I do not pretend that pointing out these patterns will necessarily bring improvement. Very much like Kafka and his characters, we in the scholarly community are not immune to the processes we describe. We often try to convince ourselves that scholarly critique has a direct use-value in chipping away at the problems of the world; that our work is slowly but surely opening up new ways of thinking that will help solve the problems we encounter; and that somehow this work is cumulative. But that’s just not the way things work. Nevertheless, if human existence is not inevitably predetermined, but destiny is “about doing one’s best in a relationship with greater powers” (Schielke 2018: 344), then understanding how those powers work on us is crucial. Such understanding requires ongoing, persistent thought. It requires thinking and rethinking even, or maybe especially, about things we thought we had already figured 13 I have written about this problem in greater detail elsewhere. See Dalsheim (2013a). 14 Unusual comparisons are foundational to anthropological thinking. Laura Nader’s work (e.g., 2001) provides one of the best examples of the power of putting familiar information together in unfamiliar ways to provoke fresh thoughts about fundamental elements of human society.

18 Israel Has a Jewish Problem out. As should be clear from the preceding pages, I am not the first to think about how nationalism works to produce its populations, about the relationship between nationalism and colonization, or about the problems of citizenship and sovereignty. Despite so many predictions of nationalism’s demise, these questions remain relevant, the problems still plague us, and good answers, it seems, “must be reinvented many times, from scratch” (Powers 2018: 3).15 This book is filled with stories of people’s lives. Some of them are amusing, absurd, or just counter-intuitive. I hope that readers will find cause to laugh along the way. But the overall story is anything but funny. It is a tale of what is involved in squeezing people off the land into cramped spaces or open-air prisons. It is a tale of what is involved in displacement and dispossession at a time of dwindling natural resources. Some people will not have water to sustain them. That is the story of Palestine. Increasingly it is also a global story about who will have comfortable lives, who will suffer, and who will survive. To participate in squeezing people off the land, this book argues, involves not only the destruction of other people’s lives. It also necessarily involves forms of self-destruction in ways that may be far from obvious.

15 Post-colonial and critical race scholars point not only to a rise in exclusionary forms of nationalism, but specifically to “a massive rise in virulently racist and intolerant forms of ethnoreligious nationalism, with Zionist nationalism in Israel being an extreme case of what is fast becoming the rule rather than the exception” (Ghassan Hage 2016: 124). This is not to say that Zionism is the worst of all nationalisms, but that it is worth studying as an example of broader patterns. Zionist nationalism, and its settler colonial structure, has been thought of as a model for much broader contemporary processes from policing and building walls to removing people from their land and livelihood as the planet heats up. For example, see Lentin (2008) and Collins (2011).

1 Before the Law There Stands a Jew Before the law stands a gatekeeper. To this gatekeeper comes a man from the country who asks to gain entry into the law. But the gatekeeper says that he cannot grant him entry at the moment. The man thinks about it and then asks if he will be allowed to come in later on. “It is possible,” says the gatekeeper, “but not now.” —Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”1

Scene One One day, a middle-aged woman working as an administrator in a public high school near the coast in Northern Israel received a call on her cell phone. Rina2 didn’t recognize the number but answered anyway. It was an official call from a government agency. The state- sponsored Rabbinate, the central authority on Jewish religious law,

1 Kafka’s “Before the Law” originally appeared as a scene in the novel, The Trial. The version quoted throughout this chapter was reproduced as part of an edited collection of Kafka’s stories (Kafka 1971a). 2 Like all the names in this book, Rina is a pseudonym. The names and certain identifying traits have been changed to protect people’s privacy. In addition, some of the characters in this book are composites of a number of people who were part of the research for this project. Some of the stories are likewise composites. Some ethnographic tales are combined or supported by stories reported in the news. In this case, Rina’s story includes information I gathered among a number of people, combined with Gershom Gorenberg’s (2016) reporting. Israel Has a Jewish Problem: Self-Determination as Self- Elimination. Joyce Dalsheim, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190680251.001.0001

20 Israel Has a Jewish Problem was calling her to come in for an interview.3 It seems something about her Jewishness had been called into question. The woman had been married twenty-five years earlier in a ceremony conducted by the same Rabbinate, who would not have performed a Jewish wedding then if she wasn’t Jewish. And yet they were questioning her Jewishness now. “It must be a mistake,” she told the voice on the phone. “No. No mistake.” If her Jewishness was considered uncertain, then the Jewishness of her children would also be questioned. That could interfere with their ability to marry and raise children. One of her sons had recently decided to get married. Suddenly, the whole world seemed to be turning upside down. At first, Rina thought maybe if she just ignored the phone call they would forget about her. The whole thing would just go away. Anyway, she thought, “I am an Israeli. I am a Jew. This is my country. I grew up here and served in the army here. How could anyone question me?” Rina’s loyalty to the state was not at issue. It was her pedigree, her ancestry, her genealogy. Who were her parents and grandparents? Grandmothers in particular were of interest, as Jewishness is generally determined matrilineally. Where did her great-grandparents come from? Had their little village in the Ukraine maintained Jewish customs? Could she prove that both her paternal and maternal great-grandparents were Jews who married Jews and had Jewish children? When the Rabbinate called again, she realized there would be no easy way out of this predicament. Perhaps it would be an annoyance, but certainly nothing more than a bureaucratic matter. 3 The Rabbinate in Israel refers to the state-sponsored office with authority over religious law. The Rabbinate has jurisdiction over many aspects of life for Jews in Israel, including marriage and divorce, burials, conversion, kosher certification, and supervision of holy sites. The Israeli Rabbinate determines who is and who is not a Jew, which is central to gaining citizenship.

Before the Law There Stands a Jew 21 Israelis are used to the annoyances of bureaucracy. Reluctantly, but resigned to rectify whatever the problem was, she arranged an appointment. When she arrived at the offices of the Rabbinate, the questions came at her so fast she wasn’t at all sure she could answer. Did her great-grandmother on her father’s side who came from Argentina speak Ladino? What proof could she offer? Was her great-grandfather’s grave in the Ukraine marked with Hebrew lettering? Could she provide a photograph? A bill of sale for the headstone? Rina left the office of the Rabbinate confused and distraught. At dinner that evening she told the story to her husband, who laughed in disbelief. “Just consider our name,” he said. “What person named Goldberg could be anything but Jewish! This is just ridiculous.” It was neither amusing nor ridiculous, Rina thought. She began to have nightmares. Rina’s imagination was running away with her. Her anxious dreams became grossly exaggerated. But the rest of the story is not a dream. Indeed, the Rabbinate has recently been calling on Israeli citizens, sometimes in ways that seem quite random, asking for proof of their Jewishness (Gorenberg 2016). Here in the self-defined Jewish state, the country that promised liberation for an oppressed and persecuted people, Jews are being questioned about their Jewishness. Often the phone call comes when people’s children are poised to marry. Some people laugh and others become infuriated. Still others, especially those who have converted to Judaism, are seriously concerned that problems could arise for their children or grandchildren.4 “Before the law there stands a gatekeeper,” Kafka wrote. What will it take to be let in?

4 The Israeli Rabbinate has recently made public a list of which rabbis in other parts of the world will be considered legitimate and which not, when it comes to proper conversions.

22 Israel Has a Jewish Problem

Scene Two At the moment the gate to the law stands open, as always, and the gatekeeper walks to the side, so the man bends over in order to see through the gate into the inside. When the gatekeeper notices that, he laughs and says: “If it tempts you so much, try it in spite of my prohibition. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the most lowly gatekeeper. But from room to room stand gatekeepers, each more powerful than the other. I can’t endure even one glimpse of the third.” —Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”

It’s mid-morning on Friday. An army officer decides this would be a good day to make a home visit to one of his soldiers. They are on leave for the weekend, and he wants to check up on one of his new recruits and offer some support. The officer, an observant Jew dressed in uniform with a kippah on his head, leaves home early to make sure he can return before sundown when the Sabbath begins. He travels to Jerusalem, to the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) neighborhood of Me’a She’arim. Here, one of his new recruits has recently returned home. He knows it is controversial for the strictly observant Haredi Jews to serve in the army, when in their own community it is far more highly valued to study Torah. Indeed, people in this community are opposed to service in the army. But this young man decided he should join the armed forces, and the officer wants to support that decision, to offer encouragement, and to make sure the young soldier has whatever he needs. The officer arrives and finds a place on the narrow street to park his car. He gets out and looks for the soldier’s apartment. The people in the neighborhood are not friendly. No one offers to help him locate the address, but in the end, he finds the place. He visits the soldier, who seems to be managing, but who also rather wished the

Before the Law There Stands a Jew 23 officer would not have visited him. The soldier did not want to draw attention to himself. When the soldier returned to the neighborhood on leave from the army, he never wore his uniform. He always changed into his civilian clothes, a dark suit and hat. The soldier tucked his army uniform into a bag and put his weapon away too. He walked into the neighborhood trying to appear inconspicuous, although he knew his neighbors knew he was no longer in yeshiva studying Torah like other young men his age. They knew he had joined the Zionist army. And some of his neighbors were vociferously opposed to Zionism itself. No worries. The officer must be on his way in any case. The officer must return home before sundown to observe the Sabbath. The visit was short and the officer was quickly on his way once again. But then, suddenly, as he made his way back to his car, the officer found himself surrounded by a sea of young men in black suits and hats. They were throwing stones at him and shouting. He rushed toward his car, never having imagined he would need his army training to avoid being attacked by a group of observant Jews in Jerusalem. This was no time for cognitive dissonance; he was under attack and had to make use of all his faculties to get out unharmed. The young men were furious because the Israeli government had recently passed a new law that would make conscription to the armed forces mandatory for members of their community. In the past the ultra-Orthodox had an agreement with the government. They would not have to serve in the army. They could study the Torah, worshiping God as they saw fit, fulfilling God’s commandments, which would do much more to protect the Jewish people than any army ever could. But things had changed because of the new law. Soon they would have to join the army or go to jail. The law requiring service in the army interfered with their ability to serve the Lord. It was an outrage. Some said it was nothing less than anti-Semitic.

24 Israel Has a Jewish Problem As he approached his car, the officer realized that the windshield had been cracked. He could still see enough to begin to pull away from the curb. He was frightened by the mob and by the possibility that he might run someone down. “Just imagine the headline,” he thought to himself. “Army officer runs down yeshiva student in Me’a She’arim.” He was sweating now, grasping the steering wheel and concentrating all his efforts on getting out of there without hurting anyone or getting hurt. Too late for that. He was already hurt. It was nothing serious, but there was a small wound on his upper arm where he had been struck while trying to reach his car. The following day, a secular Israeli man read this story in the newspaper. He cursed those ultra-Orthodox men in Me’a She’arim. He called them “parasites” who only take from the government and give nothing in return. They collect welfare from the state but are not willing to serve in the army like he did, like every other Israeli Jew did. He hated them. His sympathy lies with the army officer. Then, he continued reading the newspaper article and found that the officer, who was also an observant Jew, is actually a religiously motivated settler, which means he adheres to a theology that promotes nationalism and territorial expansion. It is a theology that insists that Jews have a responsibility to dwell in the biblical Promised Land. This officer lives in the West Bank, in a place where Jewish settlers come into direct conflict with Palestinians, a place where this secular, left-wing Israeli Zionist thinks Israelis should not live. Those are illegal settlements and those settlers are the cause of the never-ending conflict with Palestinians. There could be two states if not for people like them. This conflict could have ended except for people like them! The secular man leaned back in his chair and pictured the army officer being attacked by a mob of young ultra-Orthodox men. He smiled to himself and thought, “Hah! He deserves it!”

Before the Law There Stands a Jew 25

Scene Three The man from the country has not expected such difficulties: the law should always be accessible for everyone, he thinks, but as he now looks more closely at the gatekeeper in his fur coat, at his large pointed nose and his long, thin, black Tartar’s beard, he decides that it would be better to wait until he gets permission to go inside. The gatekeeper gives him a stool and allows him to sit down at the side in front of the gate. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be let in, and he wears the gatekeeper out with his requests. The gatekeeper often interrogates him briefly, questioning him about his homeland and many other things, but they are indifferent questions, the kind great men put, and at the end he always tells him once more that he cannot let him inside yet. —Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”

Having recently finished his compulsory service in the Israeli Defense Forces and an additional year of voluntary national service, a young man in his mid-twenties is ready to go on a trip. He wants to travel the world, perhaps visit Europe or backpack in the mountains of South America like so many of his friends. He found a job and had been working very hard to save enough money to go away, and maybe even enough to pay for college once he’d returned. The young man, Uri, found a job in the agricultural sector. He had become quite good at milking cows and has been promoted to first milker at the dairy farm in a small community about an hour north of Tel Aviv. First milker meant that he is in charge and the other milkers would turn to him for instructions. But Uri recently realized that Mohammed, who lives in a nearby Palestinian village, was taking home a rather large paycheck. Mohammed seemed to be making more money than Uri. How could that be?

26 Israel Has a Jewish Problem It turned out that a worker could earn substantial overtime pay by working on Saturdays. Uri never had a chance to work on Saturdays. Now he asked his boss if he could, explaining that he doesn’t mind working overtime or double shifts or Saturdays. He’s just trying to earn more money. But Uri cannot work on Saturday. “Why not?” he asks the boss. “Why can Mohammed work, but not me?” Well, as it turns out, because Uri is Jewish he is prohibited from working on Saturdays. Such work would desecrate the Sabbath, and the Rabbinate has determined that if Jews desecrate the Sabbath their produce cannot be kosher. Milk that is not kosher cannot be sold in most Israeli supermarkets. “End of story,” Uri’s boss tells him. “You cannot work on Saturdays.” Uri is outraged. He doesn’t even believe in God. He never goes to synagogue, doesn’t keep kosher, and even takes great joy in eating “other” meat, the euphemism for pork in Israel. Why should he be prevented from working on Saturdays? Maybe he’d be better off if he were not Jewish, he thinks to himself. This idea is quite ironic, not only because of the history of Jews and the pressure to convert to Christianity in other parts of the world, but also given the second-class status experienced by Palestinian citizens of Israel, to say nothing of those living under military occupation. But as it turns out, Uri has little say in the matter of his own Jewishness. We will hear more about his story later (see Chapter 2). For now, suffice it to say that the Israeli Ministry of the Interior works with the state sponsored Rabbinate to determine who is and who is not a Jew. Uri is born of a Jewish mother. He cannot work in the dairy on Saturdays.

The Gatekeeper and the Countryman The man, who has equipped himself with many things for his journey, spends everything, no matter how valuable,

Before the Law There Stands a Jew 27 to win over the gatekeeper. The latter takes it all but, as he does so, says, “I am taking this only so that you do not think you have failed to do anything.” During the many years the man observes the gatekeeper almost continuously. He forgets the other gatekeepers, and this one seems to him the only obstacle for entry into the law. He curses the unlucky circumstance, in the first years thoughtlessly and out loud, later, as he grows old, he still mumbles to himself. He becomes childish and, since in the long years studying the gatekeeper he has come to know the fleas in his fur collar, he even asks the fleas to help him persuade the gatekeeper. —Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”

The stories recounted above are not fictional. They are all very real and only a few of the myriad ways in which Jews struggle over Jewishness in the Jewish state. Fragments of these struggles, and their often Kafkaesque qualities, animate the pages of this book. I speak in terms of fragments here because to fully document all the ways people struggle over Jewishness in Israel would require countless volumes and involve an endless project. Some of those struggles are well known and well documented, like the case of recent immigrants or of minority groups of Jews in Israel (see Elias and Kemp 2010). We know, for example, that many recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union have had their Jewishness questioned and have been asked to undergo conversion processes to ensure their Jewishness (Egorova 2015; Neiterman and Rapoport 2009; Kravel-Tovi 2012a, 2012b).5 We also know that immigrants from Ethiopia have not only had their Jewishness questioned and were 5 Some scholars suggest that the mass influx of non-Jewish Russian immigrants under the law of return can be understood as part of broader processes to ensure that Israel is not an Arab country (Lustick 1999). Often, being Jewish in Israel has meant precisely not being Arab. This also accounts for the ongoing discrimination against Jews from Middle Eastern countries.

28 Israel Has a Jewish Problem asked to undergo conversion by Orthodox rabbis but have also faced widespread racist discrimination (Ashkenazi and Weingrod 1987; Kaplan and Salamon 2004; Wagaw 1993). Immigration from Ethiopia (aliya) began in the mid-1970s, but it was only in 2018 that their religious leaders were finally officially recognized. The Hebrew Israelites (also known as Black Hebrews) have not been considered Jewish at all. Many came to Israel by smuggling themselves into the country and overstaying tourist visas. Seeing themselves as the true descendants of the ancient Israelites, they began arriving in Israel in the late 1960s from the United States, but have only recently begun to receive citizenship status. And we know that Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent (Mizrahim) have struggled against discrimination since the 1950s. But the focus of this book is not on minority or subaltern groups, or at least not on those people generally considered to be subaltern. Instead, it specifically deals with people considered to be at the center rather than the margins of sovereign citizenship.6 This book engages a larger question about human liberation and the promises of popular sovereignty. And at the same time, it interrogates what has been described as the contemporary secular age, and examines its outcomes for a variety of population groups. In so doing, it also raises a question about questions: the kinds of questions that scholars tend to ask and the difficulty of raising other sorts of questions. Let me begin by saying that I don’t know what it means to be a Jew. Or, at least, I do not purport to have the definitive meaning of that term, even if there is one. The point of this book is not to arrive at such a definition, nor to engage in a debate over this identifier.7 6 That does not mean, however, that all the people whose stories are told in the pages of this book are Ashkenazi Jews. Some are people whose families originated in the Middle East and North Africa and would be categorized as Mizrahim. Some are recent immigrants or their children, and others are intermarried. The general categories of difference are neither homogenous nor static. 7 Unlike Yaacov Rabkin (2016), for example, I will not begin from a particular definition of the term Jewish to determine, as he does, that modern Israel is not a Jewish state. However, I will engage with debates over this issue later in the book (see Chapter 5).