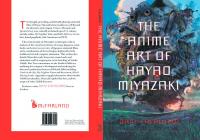

Imitation and creativity in Japanese arts: from Kishida Ryusei to Miyazaki Hayao 9780231172929, 9780231540544, 023154054X

Choosing a representative work from each of four modern genres - painting, film, photography and animation - Michael Luc

1,035 154 11MB

English Pages illustrations (black and white) [257] Year 2017

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

IMITATION AND CREATIVITY

IN JAPANESE ARTS

From Kishida Ryūsei to Miyazaki Hayao

MICHAEL LUCKEN

Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts

ASIA PERSPECTIVES: HISTORY, SOCIETY, AND CULTURE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

A S I A P E R S P E C T I V E S : H I S T O R Y, S O C I E T Y, A N D C U LT U R E A series of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University Carol Gluck, Editor Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II, by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, trans. Suzanne O’Brien The World Turned Upside Down: Medieval Japanese Society, by Pierre François Souyri, trans. Kathe Roth Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion: The Creation of the Soul of Japan, by Donald Keene Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: The Story of a Woman, Sex, and Moral Values in Modern Japan, by William Johnston Lhasa: Streets with Memories, by Robert Barnett Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan, 1793–1841, by Donald Keene The Modern Murasaki: Writing by Women of Meiji Japan, ed. and trans. Rebecca L. Copeland and Melek Ortabasi So Lovely a Country Will Never Perish: Wartime Diaries of Japanese Writers, by Donald Keene Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop, by Michael K. Bourdaghs The Winter Sun Shines In: A Life of Masaoka Shiki, by Donald Keene Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy: The Story of Kawashima Yoshiko, the Cross-Dressing Spy Who Commanded Her Own Army, by Phyllis Birnbaum

Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts From Kishida Ryūsei to Miyazaki Hayao

M I CHAE L L UCKE N Translated by Francesca Simkin

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Suntory Foundation toward the cost of publishing this book. Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright © 2016 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lucken, Michael, author. Imitation and creativity in Japanese arts from Kishida Ryusei to Miyazaki Hayao / Michael Lucken ; Translated by Francesca Simkin. pages cm.—(Asia perspectives : history, society, and culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-231-17292-9 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-231-54054-4(e-book) 1. Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.) 2. Imitation in art. 3. Kishida, Ryusei, 1891–1929—Criticism and interpretation. 4. Kurosawa, Akira, 1910–1998— Criticism and interpretation. 5. Araki, Nobuyoshi, 1940– —Criticism and interpretation. 6. Miyazaki, Hayao, 1941– —Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. nx160.l83 2016 701′.15—dc23 2015027592

Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. This book is printed on paper with recycled content. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 cover image: Sadamasa Motonaga, Untitled, 1959. Oil on panel, 35⅞ × 28¾ inches (91 × 73 cm). (© The Estate of Sadamasa Motonaga; Courtesy of Fergus McCaffrey, New York/St. Barth) cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

Introduction PART I

1

A Historical Construction

1

Copycat Japan

2

The West and the Invention of Creation

20

3

The Denial, Rejection, and Sublimation of Imitation

29

4

No Poaching

37

5

Seen from Japan

43

6

The Logic of Reflection in Nakai Masakazu

61

PART II

9

A New Place for Imitation

7

Kishida Ryūsei’s Portraits of Reiko, or, How Can Ghosts Be at Work?

8

Kurosawa Akira’s Ikiru, or, the Impossibility of Metaphor

75

107

v

CONTENTS

9

Araki Nobuyoshi’s Sentimental Journey—Winter, or, Eternal Bones

137

10

Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away, or, the Adventure of the Obliques

175

Conclusion

201

Notes Select Bibliography Index

207 231 237

vi

Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts

Introduction

In Kitano Takeshi’s film Achilles and the Tortoise, a Japanese painter successively attempts to reproduce a number of twentieth-century art styles, from Cubism via Abstract Expressionism to body art.1 Although he starts off with an undeniable gift for drawing, his talent gets progressively lost as he immerses himself in imitating Western art movements that he only superficially understands; his life then gets mired in a yo-yo of burlesque failures and family crises. Japan is often described as a nation of imitators and has—albeit with a measure of irony—assimilated this externally imposed image. And yet Japan’s is perhaps the only culture without Western roots that can boast a global reach; so often criticized for its proclivity for imitation, it has, paradoxically, become a model itself, and its artists are famous well beyond the archipelago’s borders. The history of this reversal reveals a great deal about modernity’s values, the way culture works, and the creative process. In contrast to the common perception, the relationship between copy and original, or among copies themselves, is rather complex. Mimesis, imitation, and the copy are fundamental components of human culture that, along with the notions of creation, invention, and originality, form a set that is in practice hard to divide. Anthropologists are familiar with this logic, as are specialists in classical art. “Man, maker of tools, cannot begin from nothing,” said Marcel Jousse. “We cannot apply to ourselves the Judeo-Christian concept of creation ex nihilo. We are, in reality, mere reenactors.”2 But in the modern world, imitation and creation have 1

Introduction

nonetheless been prized apart; the former has gained a largely negative connotation while the latter is put forward as humanity’s highest ideal: artistic creation, value creation, job creation, and so on. This is particularly apparent in the evolution of intellectual property laws, whose increasing need for frequent alteration raises important questions. For historical and cultural reasons that will be discussed later, modern and contemporary Japanese art is less likely to hide its debt to imitation than its Western counterpart. In order to show the reluctance of twentiethcentury Japanese art to polarize imitation and creation—in other words, to show its plasticity—I explore in this book two separate avenues. In the first, I use a selection of essays, novels, and travelogues dating from the seventeenth century to the present to examine the history of the stereotype of the Japanese as habitual imitators—and the consequences that this kind of representation has had on the way they positioned themselves vis-à-vis the West and the world. For it is important to note that Japan has not only tried to oppose the European discourse on imitation in a number of ways—including by explicit rejection, revival of traditional know-how, and the invocation of national spirit—but also assimilated and recycled this discourse, notably in relation to China. We cannot, however, simply make note of Japan’s assimilation of modern Western logic as if the value of creation were self-evident. Such a starting point could lead only to the conclusion—consistently reached in the early twentieth century—that the Japanese acculturation process was based on mere imitation, or to the parallel idea that behind this mimetic endeavor actually lies a much more creative dynamic, as maintained for example by D. Eleanor Westney, Sheridan Tatsuno, and Alain Peyrefitte in the 1980s and 1990s.3 At best, as for instance in Bert Winther-Tamaki’s Maximum Embodiment, the assimilation process can be explained on this basis: Japanese artists embodied in their art, sometimes painfully, a search for novelty and self-assertion.4 But even if this approach represents the expression of a new and welcome empathy toward them, it leaves untouched the conceptual background of the relations between East and West. The Japanese reaction has to be looked at from the perspective of a critical analysis of both the aesthetic and the political stakes of the rejection of imitation in Europe and the United States at a time that corresponds precisely to the rise and development of modern colonialism. In other

2

Introduction

words, the purpose here is neither to analyze the Japanese as scientific objects nor to discover among them such-and-such a creative skill—since that goal implies a notion of science and innovation that a priori forbids an in-depth examination of the subject—but to relativize and compare, through a historical approach, the dominant values of the modern era in Japan and the West. Thinking of Japanese culture as an entity divided “between tradition and modernity,” between a propensity to reproduce old models and a capacity to open new paths, however much a commonplace, is not yet completely outdated. There is a conceptual issue here that needs to be addressed. I contend that although contemporary Japanese artists have largely rejected explicitly mimetic devices and instead adopted the idea that they must do what has never been done before,5 they have never espoused a purely subjective attitude to creativity. This manifests itself through a taste for anything in physical matter that cannot be sublimated—that is, for its residual component. This observation, which I made a number of years ago in L’art du Japon au vingtième siècle (2001), brings me to consider now that modern Japanese art depends on a heuristic that fits into neither the classical scheme of imitation → individuation → creation, where creation is the result of the self’s maturation process through a prolonged contact with its models, nor into the modern agenda of rejecting imitation → creation → individuation, where it is only after breaking from his models that the artist can expect to find his way. In order to highlight the characteristics of the modern Japanese approach, I have focused on a selection of seminally important works: the series of portraits of Reiko (1914–1929) by painter Kishida Ryūsei; the film Ikiru (1952) by Kurosawa Akira; the photographic novel Sentimental Journey—Winter (1991) by Araki Nobuyoshi; and, finally, the renowned anime Spirited Away (2001) by Miyazaki Hayao. The use of masterpieces in a critique of creative genius may seem paradoxical, but it is not. A work’s distinctiveness and prominence do not necessarily reflect an idealization of its author’s uniqueness; they are first of all the result of a basic cognitive process,6 which is why in all cultures there are works that are considered more significant, valuable, and effective than others. But most of all, the very notion of the masterpiece allows the value judgment to be applied to the object, thus following the logic of the thing rather than of the subject.

3

Introduction

Kishida Ryūsei is a major modern Japanese painter who pioneered Fauvism in his country and later shifted his attention to European Renaissance painting. The series of portraits of his daughter Reiko, which depicts the complete development of a child from the age of three to fifteen, constitutes a remarkable attempt to explore the possibilities offered by realism at a time marked by the rapid turnover of avant-garde movements. In Kishida Ryūsei’s works, it appears that the “move to the real” took the shape of the “ghostly,” which is a recurrent phenomenon in twentiethcentury Japanese art that he arguably initiated. Ikiru (literally, “live”) is one of Kurosawa’s most striking creations. This film, which follows the last months of a man who has no hope of surviving his recently diagnosed cancer, brings to the foreground the question of “traces,” at both the thematic level (what is left from a human life?) and the aesthetic level (is an image anything other than a shadow?). Although Kurosawa possesses a consistent talent for dramatic display, the importance he gives to traces in this particular film seems like a reaction to the idea that man can overcome his fate through his own effort (labor, art . . .). The exploration of traces and shadows is another characteristic trend of Japanese modern aesthetics. Araki Nobuyoshi is famous abroad for the part of his oeuvre dealing with the gaze, sex, and desire. But Sentimental Journey—Winter does not belong to this category. This picture album, which follows the deterioration and death of his wife, Yōko, is stretched between two poles: on the one hand, the chronological movement of the huge artistic project he launched in 1971 with the first version of Sentimental Journey, in which Winter fits perfectly; on the other, a statement that says there is always something in reality that resists historical or fictional projection. That Araki chose to challenge the conceptual framework of his art project with a sentimental attachment to “residuum”—here, the bones, a primordial materiality—constitutes the third pattern that Japanese modern art developed in order to reduce the Romantic polarization between imitation and creation. Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away is structured around the opposition of two planes: the vertical realm of the Bathhouse, which refers to an artificial, violent, and anxious modernity, and the horizontal realm of the train scene, reflecting a period of calm and serenity. It is only after this

4

Introduction

two-step sequence that there is a possibility of restoring true relations between beings who, as a result, will manage to get free from their shackles. The discovery of the social link value (or en, in Japanese) is the fourth signature dimension of twentieth-century Japanese art. These four works of art, which collectively constitute a kind of system, were the starting point for this book. They set a thought process in motion, kindled a desire to describe them, and prompted critical comparisons. They generated a momentum that I have sought to maintain and not quell. This is why I will not at present delve further into the theoretical relationship between them—the theoretical level must emerge as the works are discovered and not be defined until the end of the process. As Homi Bhabha astutely points out, Montesquieu’s Turkish Despot, Barthes’s Japan, Kristeva’s China, Derrida’s Nambikwara Indians, Lyotard’s Cashinahua pagans are part of this strategy of containment where the Other text is forever the exegetical horizon of difference, never the active agent of articulation. The Other is cited, quoted, framed, illuminated, encased in the shot / reverse-shot strategy of a serial enlightenment. Narrative and the cultural politics of difference become the closed circle of interpretation. The Other loses its power to signify, to negate, to initiate its historic desire, to establish its own institutional and oppositional discourse.7

The best way to escape this phenomenon is probably not to implement an alternative theory in the sense in which postcolonialism is often understood. Any attempt to theorize in advance only reinforces the logic of domination, whether this be social at the national level or cultural at the international level. The unveiling of the Other’s meaning can be perfected only using a performative method. It implies working in situ and is embodied in the new works that result from it. The point here is obviously not to return to the naive idea that works of art speak for themselves, expressing a univocal and constant message; the meaning of works emanates from complex and fluid fields of force. The idea is to allow the otherness embodied by these works to avoid being instantly looked down on or subjected to the logic of appropriation, and instead to provide a space where, in a mediated form, they continue

5

Introduction

to affect and pollinate what lies around them—in other words, continue to live. Theoretical ambition must give way to humble description, to a relationship based on contact. The four works in some sense cover the twentieth century. Each has its unique traits and its own forces, but there are still links between them. The first link is the historical sequence they represent, which in turn allows this book to be read as an aesthetic history of modern Japan. But there are also internal and hidden links that were at first difficult to pinpoint and articulate but that ultimately made me realize that, despite the diversity of genres and contexts, I was dealing with a coherent group, woven through with similar sensitivities and issues.8

6

PA RT I A Historical Construction

1

Copycat Japan

There is a substantial body of work in English, French, and German that depicts Japanese culture as one based on copying. Such portrayals can be found in everything from eighteenth-century texts to contemporary newspapers and magazines, in works about Asia in particular or in articles on ethnology in general. “Japan’s strength is its proclivity for compilation, or as others would have it, its ‘spirit of imitation,’ ” observed André Leroi-Gourhan.1 Using the word “Japan” or “Japanese” in a passage stigmatizing a lack of imagination when it comes to action, or a lack of initiative when it comes to behavior, has virtually taken on the status of metaphor. In Les lois de l’imitation (The laws of imitation), Gabriel Tarde describes “sociable” people as having “the Chinese or Japanese capacity to mold themselves very quickly to their surroundings.”2 “Japanese,” then, just as one might say “copycat” or “chameleon.” And yet it is not so much Japanese culture that seems wedded to imitation and repetition as Western discourse about Japan. Michaël Ferrier bewails French writing on Japan, noting that it often consists of nothing more than “old stereotypes compounded by new ones—ignorance and platitudes—and a relentless recycling of outdated theories and ideas, endlessly rehashed and repeated.”3 Going back in history, one notes that neither the letters of Francis Xavier’s companions, which are some of the first European eyewitness accounts of Japan, nor the descriptions provided by François Caron, who lived in Hirado and then Nagasaki from 1619 to 1641, report any such tendency.4 Nor do Jean Crasset’s Histoire de l’église du Japon (History of the 9

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

Japanese church, 1689)5 or Engelbert Kaempfer’s seminal study Histoire naturelle, civile et ecclésiastique de l’empire du Japon (Natural, civil, and ecclesiastical history of the Japanese empire, 1727). The latter work certainly mentions the importance of Japan’s debts to China on more than one occasion, but always in a purely factual light. Kaempfer thus posits that “it is [to the Chinese] that the Japanese owe their polish and civilization”6 and explains that Buddhism and Confucianism came to Japan from the Chinese mainland.7 His only comment guilty of generalizing on this topic regards the city of Kyoto, about which he notes that “there is nothing that a foreigner can bring, that some artist or other inhabitant of this city will not undertake to imitate.”8 But in its context the comment has no negative connotations—the learned German is only attempting to showcase the vigor of industry and richness of trade in the capital of the empire. He paints a laudatory portrait of the diversity of Japanese arts, underlining their “imagination” and “unusual” character.9 More generally, he confidently credits China and Japan with “having invented early on the most useful of arts and sciences.”10 It therefore seems clear that, before 1700, the cliché of the Japanese as slavish imitators had not yet taken root. During the course of the eighteenth century, however, the emphasis on manual dexterity and intellectual tenacity got suddenly transformed into a criticism—even though this was a period when, Japan being closed to virtually all foreigners, it was difficult for Europeans to learn anything new about it. In Histoire de l’établissement, des progrès et de la décadence du christianisme dans l’empire du Japon (History of the establishment, progress, and decadence of Christianity in the Japanese empire, 1715), we therefore read that “the Japanese, who have always acknowledged themselves to be [China’s] disciples, have in virtually no area the power of invention, but everything they produce is polished.”11 The basic idea remains the same, but the angle has changed. Whereas Kaempfer was showcasing the intelligence of the Japanese and their capacity for reason, this author, Pierre de Charlevoix, reduces Japanese “ingenuity” to mere technical competence, an opinion that was to resurface in almost exactly the same terms in Histoire générale des voyages (General history of travel, 1752): “Although the Japanese have invented almost nothing, when they put their hand to something, they make it perfect.”12 This sentence was to witness considerable success, since it is reproduced exactly not only in J.-F. La Harpe’s Abrégé de l’histoire générale des voyages (Concise general 10

Copycat Japan

history of travel, 1786), which was a great publishing success, but also under the entry for “Japanese” in Abbé Migne’s Dictionnaire d’ethnographie moderne (Dictionary of modern ethnography, 1853).13 Charlevoix’s work thus seems at the root of the stereotype, but what we are dealing with here is a much broader phenomenon than the specific case of either Charlevoix or Japan. Of real importance is that, on the one hand, this comment got repeated and amplified throughout the course of the eighteenth century and, on the other, it can be found, expressed in virtually identical terms, in connection with most other peoples. The introduction to the General History of Travel thus tells us that “the Arabs did not have minds geared toward invention. They added almost nothing to the knowledge they got from the Greeks,”14 and in a slightly later work we are informed that “the Russian people are natural imitators. They imitate well and seem inclined toward everything. I know of no nation that is comparable in that respect.”15 Even the Americans were for a long time the target of acerbic comments on their inability to invent.16 Thus there is no evidence that Japan is being singled out. Discourse on the imitative nature of the Japanese is merely a reflection of Europe’s awareness of its own military and technological superiority, a fact that frequently found expression during the eighteenth century.17 It also suggests the relinquishment of the evangelical project, since imitation—primarily of Jesus—was something the missionaries sought to encourage; whereas in the sixteenth century, Francis Xavier’s companions rejoiced that the Japanese were “soft and gentle” and that their spirit was “very ready to receive the Gospel,”18 some of James Cook’s contemporaries felt only irritation and disdain, a feeling exacerbated by the related emergence of two typically orientalist themes: denial of a Japanese capacity to be individuals in their own right and a critique of the “despotism” of the Japanese princes, for whom to reign meant “taunting, persecuting, and murdering millions of men, only to then meet the same fate themselves.”19 The French Revolution and the success of Romanticism gradually quashed the advocates of classical imitation. So when Japan was brought to open its borders in 1854, no one apart from a few Christian missionaries was still suggesting that mimeticism was a good thing, and the stereotype of the Japanese as servile imitators had free rein to develop. All forms of borrowing were taken to be synonymous with degeneration and seen as inherently contemptible. Jules Michelet, writing in Le peuple (The people) 11

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

in 1846, neatly captures the short shrift given to imitation and its practitioners: “You poor imitators, do you really believe in imitation? You take from a neighboring people something that thrives there and appropriate it as best you can despite its reluctance to be adapted—but it is a foreign body that you are trying to render into flesh, it is something dead and inert; you are merely adopting death.”20 Given such a view, there was no chance of crediting the efforts of nations trying to use learning and study to narrow the scientific and technological gap separating them from Western countries. The reports of the first diplomatic missions thus mockingly portrayed Japan as sniffing out and hastily copying everything that related to foreign countries.21 In an issue of Le correspondant of 1864, an editor describes “the wonderful aptitude of its people to imitate what it sees”: According to travelers, who can illustrate it with countless instances, the faculty of imitation is carried to excess in the Japanese. Thus, for example, when foreign consuls arrived with their retinues, they bought horses and harnessed them in the European style. Just a few months later, all the natives in their service used only such harnesses instead of the ancient straw stirrups common to the country. Soon thereafter the saddler refused to take on work, saying all his time was occupied making English-style saddles for the Japanese aristocracy. These saddles were examined; they had been made exactly as they would have been by the best workers of Paris or London. And such it was with everything that was trusted to the ingenious minds and skilled hands of the Japanese.22

The stories taken from tourist accounts are similar, as we can see in Pierre Loti, who, with his usual outrageousness, writes in L’exilée, “All this servile imitation, admittedly amusing for passing foreigners, betrays in this people a fundamental absence of taste and even an absolute lack of national pride; no European race would accept to toss aside, from one day to the next, all its traditions, customs, and dress.”23 The image depicted by writers of the latter half of the nineteenth century constitutes a hyperbolic variation on that of the eighteenth. Japan is no longer just dependent on China—it imitates all and sundry. From this period onward, there is no longer just one stereotype but a whole host of stereotypes unfolding around this theme.

12

Copycat Japan

The mimetic disposition of the Japanese is not merely commented on but explicitly mocked, with mockery and ridicule basically dressing a feeling of superiority in humor. We mock what we dominate physically or symbolically and, by extension, flatter our own ego. Criticism of Japanese imitation thus belongs very clearly in a power struggle. Of course, not all Western writers gave way to caricature. Félicien Challaye, Sergei Eliseev, and Émile Hovelaque, in France, and William E. Griffis and Sidney Gulick, in the United States, all lent subtlety to, not to say refuted, the idea that Japanese culture revolved around imitation of external models. Hovelaque, for example, notes that “Japanese art is never a simple representation of reality but rather the result of the forces that create it.”24 Most of the time, however, such statements are defensive, consisting of attempts by experts to counter the dominant vision prevailing most conspicuously in novels and the general press. When it is not mocked, Japanese imitation is presented as a threat, especially in texts on military and economic topics. When, between 1895 and 1905, assertions of Japanese power and the rebellions in China called the colonial order into question, Europe got scared, worrying that the Asians would manage to turn the weapons it had given them against it. The “yellow peril” was an upset of international order, because the student had overtaken the master.25 Meanwhile, manufacturers constantly complained that the Japanese were “insuppressible counterfeiters,” whether this was in the realm of textiles, photography, equipment, or automobiles.26 “This prodigious faculty of imitation constitutes, at least for the time being, a serious danger for some of our industries,” wrote a French engineer in 1898, adding, “The Japanese are instinctively counterfeiters, and their patent legislation, far from trying to suppress this tendency, does everything to promote it.”27 The Western attitude toward Japan was thus disdainful in principle, but downright piqued and offended when its interests were at stake. The two moral weapons used alternately by imitation’s critics were contempt and a claim to exclusivity. There are even cases where the two ideas combined, as witnessed by the many American propaganda images during World War II in which the Japanese are represented as threatening gorillas or chimpanzees.28 They are ridiculous, because they are only apes, but they are dangerous, because they are beasts. In truth, it is their

13

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

“dangerousness” that, from the end of the nineteenth century onward, sets Japanese imitators apart in the Western imagination, while other nations, most of which were occupied or conquered, had been led to obedience by colonial powers. The annoyance caused by the Japanese capacity to appropriate Western models was proportional to their capacity to remain independent. In other words, it is paradoxically because they were autonomous that they were particularly reviled as imitators. This last point serves as a reminder of the political and ideological nature of the critique of imitation. Old-style colonization, underpinned by an evangelical mission, had a predatory dimension but granted imitation an important role. “Imitate us to imitate God,” it basically said. In missionary accounts, vernacular designations were avoided whenever possible; Japanese converts to Christianity were called Michael, Matthias, Joachim, and Bartholomew, and the descriptions of their lives left no room for exoticism.29 Instead, everything was done to give the reader a sense of closeness and the impression that the faithful across the world shared a communal destiny and were members of the same church. In contrast, modern colonization relegated imitation to a subordinate position. A country like France certainly attempted to transmit its history and culture to the populations under its control, often quite clumsily, but the essence of modern colonialism was the “creation” of territorial empires and trade based on the exchange of primary material for finished products. Dominated populations could not, on principle, be assimilated to the dominant group because it was not possible to concede value to the mimetic project, especially following the end of the nineteenth century and the spread of evolutionary racialism. There is thus a direct correlation between disparagement of imitation and the form that colonialism took in the modern era. This link has not always been clearly perceived, however, which is why many artists and intellectuals—often those with the best of intentions— have enjoined non-Western peoples to reject the path of imitation: “Stay Japanese!” Olivier Messiaen told his Japanese students,30 while Elian-J. Finbert exhorted, “Don’t do like us. . . . Don’t imitate us. Seek in your own history the wisdom that will nourish your soul. You will get the better of foreign domination the day that you feel masters of your own fate. We can do nothing for you. You are rich in your own right.”31 Even though these artists and authors genuinely wanted the best for the na14

Copycat Japan

tions and individuals they were addressing, they not only failed to see that their conclusions were biased from the outset by their own prejudices about imitation but also failed to understand that these prejudices were inherently related to the demiurgic compulsion at the root of modern colonialism. Denying the virtues of mimeticism and claiming the power to create a new world are two sides of the same coin. A similar mode of thought seemed to inform Annie Besant, one of the instigators of the Indian national liberation movement: “The artists of today,” she said in 1907, “lack ideals. They are more often copyists than creators. The true artist is a creator. He is original. It is not the work of a creator to simply copy.”32 On the one hand, she was campaigning for autodetermination; on the other, she was urging colonized countries to adopt a purely Western conceptual framework. The people were thus confronted with the basically insurmountable problem of knowing that in order to be authentically themselves, they had to espouse a system of logic and hierarchies that was not their own and, moreover, was the cause of their enslavement. Even though the world has seen considerable changes since the end of World War II and decolonization, the stereotype of the Japanese as imitators is far from having disappeared, especially since China’s emergence on the global economic scene at the end of the 1990s has tended to resuscitate this idea of Asia in general.33 In 1991, a sociologist recorded the following comment made by a young Frenchman working in a clothing store: “Japan is a world of copies. The Japanese have a knack for improving things imported from abroad but don’t know how to create things themselves.”34 The image born at the beginning of the eighteenth century is thus still alive, notably among the petty bourgeoisie and general public. It has also been made to conform to intellectual fads. The most characteristic example is captured in this excerpt from a work published in 1970: “Japan brashly copies and recopies. The child of a civilization based on wood, a perishable material, the Japanese make no distinction between copy and original.”35 For this author, the point is not merely to mock or show outrage at the use of imitation but also to grasp the essence of the phenomenon and attribute it to the natural order. Since Japanese imitation can no longer be explained as an attempt to catch up with the West— this phase being finished—a deeper reason must be found to explain it. It is clear, however, that the Japanese can and do distinguish copies from originals, as their museums’ acquisition policies, heritage classification 15

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

system, or simply their art market bear ample witness. The direct violence of colonial discourse was thus replaced by a form of structural fascination that can still be found in recent best-selling authors such as Arthur Golden and Amélie Nothomb. Japan no longer copies, but it has a relationship with imitation that is special, not to say rather difficult to fathom. After Japan became the world’s second-biggest economy in 1968, and also, or especially, after the appearance of postmodern theory and postcolonial studies, new discourses began to emerge. Among scholars in the humanities and social sciences, no one would now dare say that Japanese culture is by its very essence mimetic. “How can we assert that the Japanese are mere copiers?” asked Alfred Smoular in 1992.36 More recently, Alain-Marc Rieu quipped, “Japan the imitator? A contradiction made by those who believe themselves to be the model or the norm.”37 Qualifying, refuting, or criticizing the idea that non-Western people have a propensity for imitation is now standard practice in scholarly circles. And judging by the views of current students—that is, the generations born after 1980, for whom Japanese-produced manga, anime, and computer games are key cultural references—the association between the Japanese and imitation makes no sense. That stereotype is in the process of disappearing and being replaced by the opposite idea: that Japan is a creative country. It is not certain, however, that the conceptual framework that currently prevails in Japanese studies marks a complete break from the one that reigned at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the archipelago was immersed in the process of acculturation; imitation has a more negative connotation than ever, and everything is done to lower its value ever further. So much so that, wherever it appears too conspicuously, convention favors turning a blind eye to it. It therefore tends to get reversed or transformed into something positive, by explaining, for example, that it is just a preliminary stage or the expression of a sophisticated method: “Contrary to popular belief, the creative refinement of the Japanese is not merely product imitation or copying. It is a disciplined method for transforming an idea into something new and valuable,” explains Sheridan Tatsuno.38 In the 1990s, Alain Peyrefitte thus maintained that Japan had been driven for centuries by a principle of “creative imitation,” adding, “True imitation consists of mastering re-creation, genuine change is below the surface.”39 So this must mean one of two things: either this type of argument indicates a new definition of imitation and creation, or it 16

Copycat Japan

marks a new stage in the polarization of imitation and creation whereby imitation, finding itself reduced to the status of a subsidiary modality of individual and national genius, no longer exists as such, being in its “true” form necessarily “creative.” Even though these arguments tend in this case to rehabilitate Japanese culture, one must be careful to assess whether any given instance is not more of a headlong rush into fanciful speculation than a conceptual change. Certain aspects seem to call for cynicism, particularly the enduring popularity of the descriptive mode that is summarized by the well-known characterization of Japan as lying “between tradition and modernity.” This idea has been particularly popular since the 1970s. Even today, it remains one of the key frames of reference for French secondary-school students. From an ethnological point of view, it is a trite and facile commonplace; cultures are almost always the result of interactions between internal and external forces. In order to understand what lies behind this perception, it is necessary to look to the past. We can begin with Basil Hall Chamberlain, one of the first great European Japanologists. In a work of 1890, he wrote that “the ingrained tendency of the national mind towards the imitation of foreign models does but repeat today, on an equally large scale, its exploit of twelve centuries ago.”40 Following the example of most of the authors cited earlier, Chamberlain emphasizes the Japanese propensity to transpose foreign realities into a local context. But this is not the only way to couple Japan with the idea of imitation. In 1947, Robert Guillain, director of Agence France-Presse’s Tokyo office during World War II, was able to assert that Japan “belongs to a civilization whose main concern has been, for thousands of years, to neither invent nor progress, but instead to keep the world still and just as it has been bequeathed to each generation by that which preceded it. To create, for the Asian artisan, means to copy. He cannot imagine that an object could be anything other than the copy of a model. The student who invents rather than imitates is rejected by his master.”41 This perception of Japan is far from having disappeared: political essayist Jacques Attali still speaks of Japanese civilization as an ancient and immutable one.42 It is thus asserted, on the one hand, that the Japanese spend their time copying other nations—which implies permanent change: the Japanese are “novelty addicts,” claims André Bellessort— while, on the other, that they never invent anything and aspire only to keep repeating themselves.43 Unbothered by this absence of coherence, 17

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

the priority of its critics seems to be to link Japanese culture to a paradigm of imitation with negative connotations. During a large part of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the picture proposed by Japan experts, and intellectuals in general, followed one or the other of these two main branches of the mimetic paradigm summarized by Chamberlain’s and Guillain’s quotations. The first sees the consequences of espionage, counterfeit, versatility, and modernity, and from the second derive the concepts of immutability, conservatism, tradition, and a lack of originality. Contrary to appearance, they are not unrelated. They stem from the same root. Over the years, a number of authors have noted the existence of these two dynamics—without, however, seeing what they had in common. As early as the turn of the twentieth century, Michel Revon proposed a complex blueprint to describe Japanese culture: “Japan strikes us as an extraordinary creature that has fed by turns off the Eastern and then Western cultures without, for all that, losing its own native culture—which is precisely the crux of Japan’s genius: to assimilate completely what it has drawn in from the outside and render all foreign importations its own.”44 Revon drew attention to the combination of the two types of imitation that I have identified: one external and synchronic, the other internal and diachronic. But the coexistence of the “copies-modernization” and “repetition-tradition” pairings at the heart of Japanese culture strikes him as extraordinary. Such a reaction is normal if the debate is framed in this way, but what we are dealing with here is in fact not a real dialectical opposition. If we compare these two types of imitation, or measure the distance between them, what emerges is a schizophrenic effect, as if they were two autonomous forces working in opposite directions.45 History shows that this apparent opposition merely conceals two ways of saying the same thing: that Japan harbors a culture that is noncreative, imitative, and servile. In other words, the concepts of “tradition” and “modernity” are neither contradictory nor unrelated, but rather proceed from the same reasoning and are structurally linked. We have now seen that the theme of imitation in Western critiques of Japan has a history; it has an origin and various phases, even if we cannot yet know where they will lead, and this topic is complex in any case because it allows the articulation of contradictory-looking positions. The issue of imitation and the negative connotations it carries are the nodes 18

Copycat Japan

around which Roland Barthes’s “ideological occultation” of Japan has secretly and unconsciously taken shape—that is, the refusal to let this culture be part of history and, more generally, to be appreciated in a subtle and reasoned way.46 The question of imitation does not, however, merely probe the Western outlook on Japan, Asia, and all things foreign. It is also one of the blind spots in the West’s examination of itself, which we will now explore in both its aesthetic and historical dimensions.

19

2

The West and the Invention of Creation

Although the history of art and literature since the eighteenth century has developed on the basis of showing the “originality” of classical masterpieces, many French painters of the seventeenth century followed rules of representation that differed little from those of the same period in Japan. In his discussion of the transmission of artistic skill during the Edo period (1603–1867), Christophe Marquet notes, “The recommendation to rely on the example of great masters of the past to achieve mastery of one’s art is in fact fitting to all academic traditions. It is formulated in a roughly identical way in Europe during this same period.”1 Among the painters of the Kanō school, as with many painters of the Académie royale de peinture, respect for the master and for models was an essential and nonnegotiable element in an artist’s training and career. The similarity between two painters or poets had to be, to use Petrarch’s image, akin to the similarity between a father and son, immediately recognizable as being related and yet different.2 Likewise, the Chinese maxim wēngù zhīxīn (Learn new things by reviewing the old) was applicable on both sides of the Eurasian continent. But by the nineteenth century, the parallel between Europe and Japan no longer holds. Whereas the Kanō school pursued its slow rhythm of transforming models, European art had changed its pace and direction. Although this is something of a paradox, one might say that the Europeans invented the process of creation, just as, to use Max Weber’s expression, they invented tradition—two phenomena that are in fact connected.

20

T h e We s t a n d t h e I n v e n t i o n o f C r e a t i o n

The archaeology of the idea of creation, like those of genius, invention, originality, and imagination with which it is associated, was undertaken at the beginning of the twentieth century by Edgar Zilsel.3 Since then, it has been developed by a number of philosophers, historians, and sociologists, most notably Michel Foucault, Thomas McFarland, and JeanMarie Schaeffer.4 All agree that a fundamental change took place during the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For Schaeffer, it is during the “ancients versus moderns” debate at the end of the seventeenth century that “people begin to entertain the idea that working within established rules might be incompatible with the development of a great work of art.”5 This would corroborate the theory that negative commentary on the imitative nature of the Japanese (and East Asians in general) began to emerge at the beginning of the following century. There is here, as so often, a direct correspondence between the aesthetic and the political. On the philosophical level, this phenomenon can be linked to attempts to demonstrate man’s capacity to be the heir of God’s omnipotence. By maintaining the self’s a priori existence, Descartes had given conceptual autonomy to the idea of creation, simultaneously relegating imitation, whether Platonic or Christian, to the premodern order. He thus opened the way not only for the philosophy of the Enlightenment but also for Romanticism—two movements that, despite all their differences, share the idea of the creative individual freed from the duties of theological imitation. However, although the idea that human beings have not only the possibility but also a form of moral and spiritual duty to produce “new” and “original” things took root in the seventeenth century, it was still first and foremost through and for God. “Creator,” written with a capital C, was still God’s exclusive prerogative. The most decisive step on the path to asserting man’s free creation took place toward the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, at the time of the French Revolution and the advent of German Romanticism. “Genius,” wrote Kant, “is the exemplary originality of the natural gifts of a subject in the free employment of his cognitive faculties.”6 Hegel, eliminating nature, reformulated this as follows: “The artist must act creatively and, in his own imagination and with knowledge of the corresponding forms, with

21

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

profound sense and serious feeling, give form and shape throughout and from a single casting to the meaning which animates him.”7 Hegel’s aesthetics, which sees art and the ability to create as two of the highest capacities of the human mind, is foundational to the contemporary world. But its corollary is to question the value of imitation, since it implies that models can be given only as examples, in Kant’s words, “to be followed” and “not to be imitated.”8 From his predecessors, an artist can adopt only an attitude or a type of heuristic positioning, but not form or even methods. Since all forms are integrated as and when they arise in the finite realm, it is necessary to be continually original in order for the mind to free itself and maintain its own ideal. Oddly, Kant and Hegel use the same example to illustrate this point, that of the nightingale’s song. The argument of the two philosophers is that the beauty of the bird’s song is linked to its natural origin, and that the same sound produced by an imitator cannot be enjoyed once one knows it does not have natural origins. “As soon as it is discovered that it is a man who is producing the notes,” writes Hegel, “we are at once weary of the song. We then recognize in it nothing but a trick, neither the free production of nature, nor a work of art.”9 This parable is not used to question the effects of imitation (one can certainly be fooled) but rather its principle. The very fact of knowing that a work is an imitation a priori ruins its aesthetic value. Only the free creation of the mind by itself, or of nature by itself—here, the nightingale—earns inclusion. The feeling of being able to enjoy only an original work and not its reproduction is directly linked to this concept of art. What we see at the philosophical level can also be found in artists’ discourse and practice. What happened between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, and in certain respects up to the present day, is an uncoupling, a growing imbalance between and polarization of concepts— conservation and invention, imitation and creation—that were originally conceived of as inextricably linked and were generally inversely hierarchized. It is not until the end of the nineteenth century, and especially the beginning of the twentieth, that we see a radical rejection of imitation and the possibilities it offers, both at the level of discourse and in the works of art themselves. “I am not capable of servile copy,” wrote Matisse, “for me, everything lies in the conception.”10 This trend, which reflects the idolization of the human mind and a disenchantment with nature, is particularly 22

T h e We s t a n d t h e I n v e n t i o n o f C r e a t i o n

noticeable in the realm of fine arts. Expressionism, and then its abstract version after World War II, as well as all the work based on it, developed in accordance with the principle of “creativity.”11 Its implications are much broader, however. Modern science exists only on the basis of discoveries and inventions. At the social and educational levels, France’s civil unrest of May 1968 and similar protest movements demonstrated a desire to break with teaching methods that relied too heavily on reproducing models and not enough on the imagination. The paradigm manifests itself again and again in all manner of contexts. In terms of its symbolic value, imitation keeps losing ground, chased from one domain to another, while the promotion of creation is becoming hegemonic and universal. It is a long process—a real civilizational axiom—that has its own history, heroes, and mythological dimension. Let us return to Kant and Hegel, who played a significant role in establishing the philosophical terms of this development. Their position is not without contradictions, which is particularly apparent in the way they choose to express themselves. Kant makes an especially revealing choice of words, declaring, “Every one is agreed that genius is entirely opposed to the spirit of imitation.”12 To highlight the power of “genius” and belittle what he later refers to as “aping,”13 Kant uses the argument that he is not alone in seeing things this way and that everyone thinks as he does. In other words, he criticizes imitation by claiming that his view is commonplace. The subtext of this somewhat oxymoronic stance is that Kant sees social value in the concept of genius, and that pure creation needs to be validated by a collective authority. The same process obtains in Hegel, but in the more transparent and fearsome form of “we,” of the plural and impersonal pronoun (wir, uns). With the Romantic “we,” the Cartesian ego gets detached from divine reason and recycles its transcendence in a collective form. And yet both Kant and Hegel are aware that attitudes to imitation were not always as they described them. This is particularly true of Hegel, who compares the Romanticism of painting since the Renaissance with Greek sculpture, in which the material is always the essential principle; sticking to the material world was part of classical art’s agenda. The collective authority to which they refer, although founded on a form of deification of subjectivity, is thus not absolute. It postulates a form of universality and transcendence, following the example of the ecclesiastical “we,” but 23

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

in practice the Romantic “we” is fundamentally relative. It does not refer to man regardless of his era and location but, on the contrary, actually implies a “them.” This “them” refers as much to an Otherness stemming from diachrony—we the moderns, them the ancients—as to a spatial Otherness: us here, them over there. Le tour du monde, a travel magazine published in the second half of the nineteenth century, is packed with comments associating ancient and distant civilizations with imitation.14 One traveler passing through Mesopotamia noted that in Assyrian art of the past “the spirit of imitation . . . is visible in all the major monuments.”15 Another, having made a stop in Fiji, enjoyed the dances performed by young villagers, “which proved their advanced faculty of imitation.”16 We thus arrive at what Dominique Château said of orientalism in painting: “The notion of exoticism bridges distance across space just as well as distance across time; they are interchangeable.”17 The faraway and the ancient overlap in the colonial imaginary, and the mimetic mind-set is perceived to be one of the main traits that unites them. To make a distinction between “we” or “us” and “them” is to perceive a discrepancy that is essentially vertical and hierarchical. In this respect, the Romantic “we” is not greatly different from the basic anthropological system that always tries to link feelings of collective identity to a sense of opposition to a neighboring group. The difference is that the Romantic version gets conceptually recast, systematized, and extended. Beginning in the nineteenth century, a perfectly graduated scale stretches from the here and now of the “we,” associated with positive values and progress, to the distant world of the “them,” considered negative, primitive, and backward. This separatist mind-set will find application in a large number of fields: in history and geography, where the idea of the West gets honed and reinforced; in linguistics, through the concepts of Indo-European language and “Nostratic” language; and, a little later, in physical anthropology, with the theory of the Aryan race. Debates about imitation are one of the theoretical keys to this process. In this respect, the following excerpt from Herbert Spencer’s Principles of Sociology is not only typical but also almost absurd in its failure to see that quoting, reporting hearsay, and repeating oneself are nothing but different modes of imitation: There was but little originality in the middle ages; and there was but little tendency to deviate from the modes of living established for the various 24

T h e We s t a n d t h e I n v e n t i o n o f C r e a t i o n

ranks. Still more was it so in the extinct societies of the East. Ideas were fixed; and prescription was irresistible. Among the partially-civilized races, we find imitativeness a marked trait. Everyone has heard of the ways in which Negroes, when they have opportunities, dress and swagger in grotesque mimicry of the whites. A characteristic of the New Zealanders is an aptitude for imitation. The Dyaks, too, show “love of imitation”; and of other Malayo-Polynesians the like is alleged. Mason says that “while the Karens originate nothing they show as great a capability to imitate as the Chinese.” We read that the Kamschadales have a “peculiar talent of mimicking men and animals”; that the Nootka-Sound people “are very ingenious in imitating”; that the Mountain Snake Indians imitate animal sounds “to the utmost perfection.” South America yields like evidence. Herndon was astonished at the mimetic powers of the Brazilian Indians. Wilkes speaks of the Patagonians as “admirable mimics.” And Dobrizhoffer joins with his remark that the Guaranis can imitate exactly, the further remark that they bungle stupidly if you leave anything to their intelligence. But it is among the lowest races that proneness to mimicry is most conspicuous. Several travellers have commented on the “extraordinary tendency to imitate” shown by the Fuegians. They will repeat with perfect correctness each word in any sentence addressed to them mimicking the manner and attitude of the speaker. So, too, according to Mouat, the Andamanese show high imitative powers; and, like the Fuegians, repeat a question instead of answering it.18

From this description, Spencer reaches the conclusion that there is an “antagonism” between the different races and periods of humanity, and that on one side of the evolutionary schema there is a “we” that rejects imitation and is drawn to originality and, on the other, nations that show “a smaller departure from the brute type of mind.”19 One group is caught up in the movement of history, the other remains in an ahistorical suspension. However, in order to get a complete vision of the world of mimesis that implicitly defines the territory of the Hegelian “we,” one needs to add to temporal and spatial difference sexual difference, on the one hand, and an intellectual and social difference, on the other—we the refined people, them the vulgar ones. Indeed, one finds in some nineteenthcentury authors the idea that women are “very susceptible to imitation.”20 25

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

More commonly, we hear that women are not capable of acting on the world: “In intellectual constitution as in physical constitution, women are passive,” writes a doctor in 1853.21 Similarly, the general public, the masses, are described as inclined to appreciate only the imitative arts. Baudelaire thus lambastes photography at the end of the 1850s in the following terms: Where painting and sculpture are concerned, the current credo of the general public, especially in France, is as follows: “I believe in nature and I believe only in nature. I believe that art is and can be only an exact reproduction of nature. So any method that could give us a result identical to nature would be absolute art.” A vengeful God granted the wishes of this multitude, and Daguerre was his Messiah. So the multitude said, “Since photography gives us a guarantee of accuracy, then art is photography.” From that moment onward, the vile people rushed, like a unified Narcissus, to contemplate their trivial reflection on metal.22

The rejection of institutions like waxwork museums or realist innovations like three-dimensional cinema, common among intellectuals, is of a similar nature. All critical discourse on imitation from the nineteenth century to today contrasts an inferior historical, geographical, or sociocultural referent with a superior “we,” whose characteristics, discernable through contrast, are to be evolved (temporal superiority), imperial (spatial superiority), male (sexual superiority), and bourgeois (intellectual and social superiority).23 Emphasis on discrepancy is what motivates all the claims of temporal, spatial, and social difference. The invention of creation consisted in placing the modern individual at a distance from both God and nature. From that point onward, two approaches—two modernities—became available. The first, based on poetic order, plays on the different possibilities of positioning the ego vis-à-vis the world, leaving it undetermined. This is how all great artists have lived their art. The second, which derives from political order and is of more interest here, tends on the contrary to define the ego, to establish its parameters and calibrate it. The role of the artist is objectivized within frameworks such as the nation, a social class, or even a style.24 Once again, this is not without contradiction. But the contradiction relates to the object and the relationship established with it and not to the subject. According to this reasoning, that which is proximate 26

T h e We s t a n d t h e I n v e n t i o n o f C r e a t i o n

cannot be imitated or serve as a model. The proximate is not conducive to creation. Indeed, that which is proximate is protected: someone, who is likewise nearby, holds the rights to it. What is far away can, however, be used as a model. When Van Gogh copies Hiroshige or when Picasso uses the shapes of African sculpture, they are thought to be creating. But that which is far away is not itself a creator. The faraway does not invent or progress; it imitates slavishly. The contradiction is therefore as follows: that which is far away is the product of the sterile and negative mimicry of the Other, but it can be imitated in a positive and creative way by “us.” This contradiction was made possible by the Hegelian exchange of attributes between “I” and “we,” with the “I” lending transcendence to the “we” and the “we” conferring worldliness on the “I.”25 At once transcendent and relative, the modern Western bourgeois “we”—in other words, the Romantic “we”—gives sanctuary to the works of the individuals of which it consists because they are the guarantors of its sacredness, but precisely because it is the agent of the sacredness of individuals, it has trouble accepting that somewhere else there is another, similar “we.” The relationship between “we” or “us” and “them” is necessarily asymmetric. A French artist in 1900 cannot come too close to copying the work of another French artist, because the latter is protected by society, but he can take a contemporary Japanese work, or one from ancient Greece, and breathe life into it. Non-Western artists, though, are confined to either imitating their own pasts or imitating the West. In neither case, of course, can they be credited with a capacity to create. In the modern context, imitation is an inherently degrading action, whereas being imitated, imposing on others a certain way of thinking or doing things, is perceived in a positive light. The one who forms another in his image—these days, we should perhaps say who informs—not only holds the political and social power but also fulfills the requirements of human genius. By putting himself forward as a model, by rejecting imitation, and by framing his knowledge of others at a conceptual level, the genius-model can admire himself and feel reassured of his divine nature. Conversely, those who do the imitating only increase their models’ contempt for them. Moreover, if the Romantic “we” tends to deny everything that, outside itself, could claim to resemble it, it is not internally appeased for all that. The individuals who make it up are in effect rivals in the quest for 27

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

what can allay their metaphysical fears and flatter their pride. In the universe of what René Girard dubs internal mediation, where “each imitates the other while declaring the precedence of his own desire,” the foreign, the elsewhere, the distant past, and the popular masses are particularly prized conquests.26 When Edmond de Goncourt related his discovery of Japanese art, he wrote, “At the very beginning it was a few eccentrics, like my brother and myself, then Baudelaire, then Burty, then Villot . . . , then, after us, the painter gang.”27 The orientalists hunted in packs, but with each new catch competition set in, as Goncourt’s use of anaphora suggests. Everyone strives to be original, but everyone keeps a keen eye on everyone else. Romantic creation implies both imitation of the rival’s desire and a fantasy of discovering, or rather violating, the world. Affirmation of the creative power of “I” and “we”—“I” and “we” understood in a political sense, like a fixed, stable worldly power that places objects at a set distance, and not in the poetic sense—is a powerfully effective cultural device. It speeds up the temporality of experience in that it postulates the uselessness of waiting for the master and student to agree that the former has nothing more to teach the latter. Denying alterity, it also opens the way for conquest, and it allows quick profit, fulfillment of pride, and the illusion of salvation through inscription in history. It is the basis for the mechanization and calibration of social time, modern colonialism, and the assaults imposed on a version of “nature” that is its passive and objectified corollary. In other words, it is what we are. This must be our starting point. It would be a mistake to think we could turn the power of this logic against its own effects, that we could, by affirming individual or collective will, remove ourselves from a world based on the expression of individual or collective will. It would be naive and hypocritical, and all nineteenth- and twentieth-century art history shows that it serves no purpose. Conversely, thinking about the concept of imitation and examining it in situ is another step in the lengthy journey toward a reformulation of the relationship between the “we” and the “other.” The goal here is neither to return to imitation or classicism nor to surmount the imitation–creation dichotomy, but lies in the very process of reconfiguring the relationship between the subject and object.

28

3

The Denial, Rejection, and Sublimation of Imitation

In the industrial and postindustrial universe, the individual considered to be most creative imposes his model and wins a competition that operates simultaneously at the material, symbolic, and ontological levels. The same applies essentially to corporations and countries. The question of creation and imitation, in other words, incorporates high-stakes issues on which the power dynamics between people are based. Anyone acknowledged as a creator is in a position of strength; anyone subjected to a model must be dominated. In the arts, this latter type is generally disregarded; in the salaried world, he labors under humdrum conditions and has limited possibilities of development. In both cases, he is economically disadvantaged. At the same time, professions like the artisan and craftsman, which resist this polarization and the nature of whose work involves both creation and reproduction, are kept in a precarious and subordinated position. The difficulties faced by computer programmers—the artisans of today— in getting decision-making responsibilities in companies stems from the same reasoning. However, despite creation’s symbolic value, “creators” depend on words and concepts that have been forged by others. Similarly, production practices, whether artistic, artisanal, or industrial, depend on codified locations, temporalities, and routines. It is also necessary to know what has already been done, if only to differentiate oneself from it, just as it is difficult not to resort to reproduction in order to disseminate and publicize one’s work. Not only is creation ex nihilo a utopian fantasy, but there is not a single step in the production of a work that can be achieved 29

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

outside the mimetic economy. The position of creator is thus entirely relative. This reality does not, however, correspond with the demand for genius and difference engendered by history and required by society, which is why it is necessary for artists and critics to resort to legitimization strategies aimed at obscuring or distracting attention from the role of imitation in art. The first of the strategies aimed at asserting one’s creativity is both the most crude and the most widely practiced. It consists in denying or belittling the creativity of others—of which we have already seen several examples—all while concealing in one’s own work anything that might stem from imitation. This is the case, for example, of painter Franz Kline, who always refused to admit even the slightest influence of Far Eastern calligraphy on his work. His position can be explained first and foremost by a desire to defend the “originality” of his painting at a time when American art was still concerned with emancipating itself from French art; unsurprisingly, denial is often preferred to an admission of weakness. Nineteenth-century stories of the efforts made by European workshops to acquire the secrets of Far Eastern ceramics reveal a fundamentally identical attitude, if in a slightly different form. When it comes to saying that the Chinese or Japanese copy a given technique or method, the tone is contemptuous, but when the imitative relationship is reversed, the tone is everything but. Léon de Rosny thus made a glowing tribute to a book that, as he wrote enthusiastically, “will soon allow the imitation of all Chinese ceramic works, and the reproduction in the West of the decorations, the magnificent and infinitely varied colors, that have been the despair of the artists of our workshops.”1 The effort to imitate is described with warmth and enthusiasm. Émile Bergerat, meanwhile, preferred to emphasize that, with regard to production at Longwy, the imitative stage was short-lived: “Far from seeking to turn the tide, they followed it, and, taking advantage of the lessons that were reaching us from the East, they determined to battle with China, Japan, and Persia. First they imitated, then they became the ones to create. Today, Longwy pottery is one of France’s foremost institutions.”2 Such methods of asserting creativity are unquestionably crude but extremely common in practice: imitation is either hidden or presented as positive or temporary. A second, barely more sophisticated method depends on the arbitrary partitioning of geographies and the covering of one’s tracks and is par30

The Denial, Rejection, and Sublimation of Imitation

ticularly apparent in the history of artistic avant-gardes. To stick with the Franco-Japanese theme, let us look at the critical works of Théodore Duret. Duret was among the first to suggest that the avant-garde phenomenon was a spur to cultural development. In an essay on the Salon of 1870, he unequivocally states his selection criterion: What will be our guiding principle in choosing a limited number of artists from among the vast army that invades the Palais de l’Industrie? It will be the possession of originality. Among beginners and the young, we will single out only those who show boldness in the way they see and feel, and in the way they represent what they have seen and felt, and who produce works imbued with a character distinct from those of earlier painters. We will systematically spurn all artists where we find only the reproduction of known types.3

Inscribing himself as a direct descendant of Romanticism, he prohibits imitation and endorses novelty. It is for this reason that he supported Monet, Renoir, and the Impressionist school in general. However, like many artists and intellectuals of his generation, Duret was also very taken by Japanese art and contributed to the phenomenon of japonisme and the taste for ukiyo-e prints. From October 1871 to February 1872, he traveled to Japan with Henri Cernuschi. Duret must have been aware, however, of the paradox inherent in praising, on the one hand, an artist’s free creation and, on the other, the beauty of multiples obtained by largely standardized methods. He therefore had to find originality in ukiyo-e. Following the principle just articulated, he began by rejecting the country’s other characteristic art forms, such as Buddhist sculpture, in which he detected Greek origins and which, to his mind, was “the least Japanese thing to be found on Japanese soil.”4 He also rejects contemporary works made under Western influence as “a horrible combination of the old Japanese style bastardized and the European style poorly understood.”5 Having cleared the way, he has only to attribute to ukiyo-e a method of production and a value system conforming to his criteria.6 The simplest solution was to consider the painters as the sole creators of the prints. He therefore ignores what editors generally asked for in their commissions—that works draw on a known model—and relegates engravers and printers to a marginal role. As for the role of writers 31

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION

in the production of illustrated books, it is quite simply ignored, as had long been the case. For Duret, an ukiyo-e print is the product of an artist obeying only his “imagination”—fantaisie—a word that recurs repeatedly in all the literature of japonisme.7 In his view, Hokusai and Hiroshige are first and foremost masters of freedom, “applying directly and by themselves the forms hatched in their imaginations.”8 Duret idealizes Japanese artists in accordance with his own values, such that their works can qualify as avant-garde, like those of the Impressionists. This goal leads to ever more imprecision. On the one hand, he takes Buddhist sculpture to be a bad imitation of Greek art on the basis that realism was exclusive to the West, and, on the other, he transforms the prints into modern and original paintings, simultaneously hiding their (notably Dutch) influences and the value they had in Japan. Duret does not, however, put ukiyo-e and Impressionism on quite the same plane. He acknowledges that Japanese art “strongly influenced the Impressionists” at the level of coloration9 and clearly articulates a parent–child relationship between the two. However, to resolve the paradox in which Impressionism is fundamentally original while simultaneously having Japanese art as a model, Duret takes care to disconnect the geographies—Japanese art may well be “original” and “imaginative,” but it does not belong to the same universe as Impressionism. “The appearance in our midst of Japanese albums and images completed the transformation by introducing us to an absolutely new coloration system,” he writes tellingly.10 The Japanese works ultimately remain nonnative references, which is why they can still serve as models. In fact, for Duret, such models are the path to the “new.” It is therefore necessary to distinguish between the principle of imitation to which avant-garde artists and critics can under certain circumstances subscribe and a discourse on imitation that participates in a legitimation strategy. Recourse to models is allowed if they are outside the usual references; in other words, if, in a purely empirical way, they give a greater impression of novelty than those already known. However, all forms of art can be criticized for their mimetic character if this bolsters the value of what they are being contrasted with. This phenomenon is not limited to the end of the nineteenth century. Although the influence of the East, Japan, and Buddhism was claimed in a positive way by a number of major twentieth-century artists like Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, and Yves Klein, the influence of the West on 32

The Denial, Rejection, and Sublimation of Imitation

Japanese artists, conversely, took on a negative value, as we can see from the collections of the major public European and American museums, where modern Japanese art is rarely to be seen and seldom highly valued. At this juncture, it is tempting to object that the two movements should not be considered on the same footing, since the Asians adopted techniques, notably oil painting, whereas the Western artists took inspiration from a mind-set that freed them from the shackles of representation. The former would thus have imitated in a mechanical way, while the latter would have made a superior work of creation. Besides the fact that this distinction makes sense only from a West-centric viewpoint, it is clear that numerous Western artists have borrowed formal techniques from Asian art. This is particularly apparent in the works of Mark Tobey, Willi Baumeister, Pierre Alechinsky, and Jean Degottex. But as we have seen, it is rare for this to be plainly admitted. It is also clear that Asian artists did not adopt only techniques. Behind the techniques, there was often a desire to reformulate the idea of freedom, a search for the sublime and, more generally, for spirituality. The most obvious sign of this is the considerable interest in Christianity shown by Japanese writers and artists at the beginning of the twentieth century.11 In fact, this asymmetry of perspective is the expression of a system: in order for the avant-garde, who renew themselves by borrowing from the outside, to be considered as the guarantors of creativity and originality despite the taboo on imitation, it is necessary for the other party’s imitative mode to be the defective one. The third method used to transform imitation into something acceptable consists in passing the model through a filter of reasoned thought or a rational technical process designed to transform the mimesis into a cosa mentale that bestows on it a form of elevation. This solution works as an extension of classicism, for which imitation had a preliminary function and corresponded to childhood, apprenticeship, and the first stage of all production, whereas genius—that is, the affirmation of difference—was perceived to be the privilege of maturity. Aimé Humbert’s famous travelogue, Le Japon illustré, was published in the magazine Le tour du monde between July 1866 and the end of 1869.12 There is a particularly large number of illustrations in this work, and they have two striking traits: they appear quite un-Japanese, or as un-Japanese as possible, and they are relatively lacking in signature distinctiveness—it is difficult to work out whom each is by. And indeed, the artists who 33

A HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION