How Good is Family Therapy? A Reassessment 9781487580377

Family therapy is one of the most widely practised psychotherapies in North America. Roy and Frankel here provide a comp

162 109 22MB

English Pages 232 [230] Year 1995

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

HOW GOOD IS FAMILY THERAPY? A REASSESSMENT Family therapy is one of the most widely practised psychotherapies in North America. Roy and Frankel here provide a comprehensive and critical reassessment of the research literature regarding the efficacy of this form of treatment. The main thesis of the book is that this research is still in its infancy and that, although important contributions have been made, much work remains to be done. The book is divided into three parts. The first offers an overview of the current state of the family therapy field. The second assesses outcome studies of family therapy on the basis oflife-stage issues. It examines the literature on family treatment with children, adolescents, and adults. The third part reviews the outcome of a host of problems treated by this method: psychosomatic and medical conditions, alcoholism, anorexia nervosa, drug addiction, and placement prevention in child welfare. The authors conclude by reviewing the state of the art in the field and defining future directions for research. is a professor in the Faculty of Social Work and the Department of Clinical Health Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, at the U niversity of Manitoba. His recent publications include The Social Context of the Chronic Pain Sufferer and Chronic Pain in Old Age: An Integrated Biopsychosocial Perspective, an edited collection of original essays. RAN JAN ROY

HARVY FRANKEL is an associate professor in the Faculty of Social Work and diretor of the Child and Family Services Research Group at the University of Manitoba. He is the author of several articles on familycentred practice.

RANJAN ROY AND HARVY FRANKEL

How Good Is Family Therapy? A REASSESSMENT

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London

© University of Toronto Press Incorporated 1995

Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada Reprinted in 2018

ISBN 0-8020-2926-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-8020-7427-0 (paper)

(§ Printed on acid-free paper

Canadian Cataloguing In Publlcadon Data

Roy, Ranjan. How good is family therapy? Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8020-2926-4 (bound). - ISBN 978-0-8020-7427-0 (paper) 1. Family psychotherapy. I. Frankel. Harvy. II. Title.

RC488.5.R681995

616.89'156

C95-93547-0

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council.

Contents

vii

FOREWORD PREFACE

xi

1 Family Therapy: An Overview 3 2 Children and Family Therapy 22 3 Juvenile Delinquency and Conduct Disorders

37

4 Adult Psychiatric Problems 59 5 Psychosomatic and Medical Disorders

81

6 Alcoholism and Family Therapy 98 7 Adolescent Drug Abuse and Mixed Emotional and Behavioural Disorders 115 8 Anorexia Nervosa

128

9 Family-Based Approaches to Placement Prevention in Child Welfare 151 10 Future Directions REFERENCES INDEX

209

185

175

Foreword NATHAN B. EPSTEIN

The practice of psychotherapy seems to be capable of generating an unusually high degree of enthusiasm and even blind faith among those in the field. Perhaps this phenomenon is necessary in order to attract and keep people working in this most difficult of endeavours - that of attempting to bring about change in human behaviour. The practice of family therapy is no exception. As one of the earliest workers in family therapy I can attest to the tremendous enthusiasm and excitement and the high level of commitment generated by the work carried out when the field was in its infancy. We all felt like pioneers discovering a new world or like revolutionaries about to succeed in overturning the old order, having found the ultimate solution to human behaviour problems. Indeed, some of the early workers began to talk seriously about solving such problems as war, poverty, racism - you name it - by the application of family therapy techniques. As the field has matured there has been a trend towards objective self-examination, which has resulted in therapy outcome research and in multiple reviews of work in the field. This book is a very welcome example of this trend. Ranjan Roy and Harvy Frankel, committed scholars, teachers, and practitioners of family therapy, present here a prodigiously exhaustive critical review of the literature. Their approach is one of scientific detachment in reporting their findings, yet at the same time they maintain their strong commitment to the field. They are very knowledgeable and skilled teachers who are interested in the development of the field of family therapy, rather than in perpetuating the mythologies that have accumulated over the years. The message of the book is sobering with regard to family therapy. Although the authors state that good outcome literature does exist,

viii Foreword and that this gives cause for optimism, they find that the amount of methodologically acceptable outcome research on family therapy is woefully inadequate. In their view, family therapy has yet to make a strong and persuasive case for its effectiveness based on hard data rather than only on claims of clinical success. As with previous, less comprehensive, reviews, this study indicates that (1) in certain clinical situations family therapy may be of some benefit - and is at least better than no therapy at all; (2) there are still no indications as to the kinds of situations family therapy is most effective in; (3) there appears to be no difference in effectiveness among different techniques or styles of family therapy; and (4) family therapy does not appear to be more effective than other forms of psychotherapy. The findings reported here are similar to the findings reported in reviews of all other types of psychotherapy; that is, the quantity and methodology of outcome research and the data concerning effectiveness were often found to be inadequate. Although these findings are sobering, neither the authors nor I feel that discouragement is justified. What these findings indicate is that the field of treatment outcome research is actually quite young and the technology of such research is at an early stage of development. As for myself, I am at present involved in a fourth generation of outcome research in family therapy. Each generation has become more sophisticated and has enabled us to look at and consider more factors in the therapeutic process. It is hoped that as this field progresses workers will be able to study satisfactorily many important factors and variables. This optimism does not deny the complex, laborious, and timeconsuming nature of this research. My research colleagues and I have been doing outcome research in family therapy for thirty-five years; although we still feel we are just at the beginning, we are becoming more comfortable and confident with our efforts. Along with the authors I feel that family therapy is a useful endeavour. But like all the major psychotherapies now practised, it hasn't quite lived up to its original promise. Serious reflection and ongoing research such as that reported here will prove useful to practitioners in their attempts at healing human illness and improving human relationships. This book is not only for practitioners and researchers of family therapy, but also for all those concerned with the current issues involved in the rapid developments and changes in the larger field of health care delivery. As the health care field becomes more entrepreneurial and

Foreword ix profit-driven there has been a strong movement to cut back on treatment, thin out the treatment process, 'dumb down' treatment teams, and in general skimp on care in order to generate profit. While some changes have been overdue and indeed welcome, there has been concern that the health care field is moving in a dangerous direction, to where profit rather than quality and effectiveness are the primary goals. To counter this concern the entrepreneurs in the field are in the forefront advocating (cynically, in my opinion) the necessity of 'quality measures' as guarantees of treatment effectiveness. While many of the measures currently in use by corporate bodies are nothing more than 'customer satisfaction surveys,' like those used in the marketing of commercial products, some corporations are now moving in a more sophisticated direction in response to pressures from knowledgeable experts in the field of treatment outcome research. We have seen many press releases, advertisements, and statements by health care corporation executives that glibly proclaim the advent of the development of satisfactory quality indicators to satisfy their 'customers.' However, anyone who carefully reads this book will realize that such statements are not yet based on fact. The field of measuring treatment outcome is extremely complex, difficult, and timeconsuming. It is a science at its earliest beginnings. This knowledge should protect us from the sales pitches of the hucksters of health care and yet give us hope for a future when we can look forward to a more mature science which will be capable of giving us meaningful and useful information on an important area of our lives. NATHAN EPSTEIN is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Brown University, and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at St Luke's Hospital in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Preface

Jerome Frank and Pal Halmos, two eminent scholars of psychotherapy, respectively described psychotherapy as a myth and an act of faith. We choose our method, be it with doctoring or some Western model of psychotherapy, based on our own indoctrination and belief in the effectiveness of that particular approach. This indoctrination, insofar as choice of psychotherapy in the West is concerned, is in significant measure a function of training. Psychotherapy, unlike some aspects of medicine, has little basis in science. The disdain of many psychotherapists for good science may require a book in itself. Suffice it to say that modern science, rooted in reductionism, is considered antithetical to family therapy. Medicine, with its deep scientific tradition, and humanistic psychotherapy, of which family therapy is a part, are somehow viewed as antagonistic. The history of family therapy is interesting in that the early proponents of this approach found justification in the biological science of systems theory for treating the whole family instead of individuals. Having proclaimed that systems theory, or a semblance of it, was the basis of new-found solutions to a multitude of human vicissitudes, they basically ignored the need to test its efficacy. Pioneers are not expected to prove the effectiveness of their discoveries. And in the true tradition of psychotherapy, disciples flocked to this and that temple of family therapy with the same passion with which therapists of bygone eras embraced Freudian, Adlerian, Jungian, and Kleinian theories. These disciples, and we among them, did not need any proof of efficacy. In fact, in the early days of family therapy, the prevailing wisdom was that this endeavour was so novel and so complex that existing methods of outcome research were simply inadequate - or even irrelevant. Again, the faith of the early proponents of this novel treatment was absolute. It was almost sacrilege to raise questions or express doubts about family

xii

Preface

therapy as the treatment of choice. Even today literature on the efficacy of this treatment is scarce. Indeed, family therapy was offered and accepted as a panacea for an incredibly wide range of psychiatric and emotional problems. It would be erroneous to think that the practitioners of this ' art form' are any more in doubt about its efficacy today than they were twenty years ago. As practising family therapists and university teachers, we are constantly amazed by the fervour with which our students become new disciples of family therapy. Despite the fact that over the past two decades a discernible body of family therapy outcome literature has emerged, many students continue to show an almost instinctive distrust of research findings. Yet, that literature, without a doubt, has begun to come of age. Although family therapy is far from the panacea that it was once thought to be, it certainly deserves a respectable place among the major psychotherapies. The motivation to write this book is directly attributable to the questions and views expressed over the years by our family therapy students. In general, the students fall into two groups. First, those who show a remarkable critical faculty for any new information. They pose questions that challenge many of the basic assumptions held by family therapists. The students in the second group not only show an uncritical acceptance of family therapy, they become its staunchest defenders. We have been intrigued and influenced by both perspectives. Our quest in this book is straightforward. We set out to find for ourselves and for our students how effective family therapy is. Does it really do all the things our elders and betters have been telling us for so long (for instance, the clinical literature is almost completely devoid of reports on unsuccessful family therapy)? Our answer to that question is rather long and somewhat laborious. This book may not be an ideal bed-time read. In general, as an endeavour, family therapy has proven to be remarkably effective where we least expected it, such as with schizophrenia (not the double-bind perspective, but the work of those like Leff and Falloon), alcoholism (Mccrady), and juvenile status offenders. In another respect, while the outcome research may be wanting in areas such as anorexia nervosa or placement prevention in child welfare, the influence of family therapy on the overall treatment and management of these complex situations is very impressive. On the negative side, we are disappointed that family therapy outcome research is only in its infancy in the treatment of medical problems and

Preface xiii adolescent drug abuse. It is hoped that this book will reveal the complex nature of our findings. In reviewing the literature we have taken certain liberties. In the main we adopted a pragmatic approach. Our focus was to examine the outcome of systems-based family therapy. By and large we succeeded in adhering to that principle, but not strictly. In part we were not able to do so because many investigators simply did not describe the conceptual basis of the therapy under investigation, and we had to decide whether the family therapy approach was systems based. In others we deliberately incorporated studies that were not strictly systems-based family therapy, because of their intrinsic merit. We made a conscious effort, with minor slippages, to exclude purely behavioural approaches to family therapy. While we were cognizant of the value of the methodological soundness of the studies, and we used conventional yardsticks for making that assessment, we did include several poorly designed early studies to show the historical antecedents to methodologically superior later investigations. Many, if not most, of the early studies were uncontrolled and could be more aptly described as clinical reports with rudimentary evaluative components. Nevertheless, in a real sense, they laid the foundation for outcome research in family therapy . We also took liberties with the definition of family therapy. Just to demonstrate the scope of family involvement, we found compelling reasons to include a few studies involving, for example, family groups. By and large, however, in assessing outcome we subscribed to the conventional notion of family therapy. Despite the digressions the focus of this book is a critical assessment of the outcome of systemic family therapy. While we included uncontrolled studies, in drawing our conclusions we placed considerably more weight on controlled studies. We did not confine the literature review to any particular period. Our goal was to include the early as well as the most recent literature available. It is, however, possible that we have failed to include all relevant literature. We excluded nonEnglish publications because of the prohibitive cost of translation. We apologize for any other omission. This book has ten chapters divided into three parts. The first part, background issues, is a single chapter that provides an overview of the various schools of family therapy. Part 2, comprising three chapters, is concerned with assessing outcome studies of family therapy on the basis of life-stage issues. These chapters examine the outcome litera-

xiv Preface ture of family treatment with children, adolescents, and adults. The third part has six chapters and is a review of the outcome of a whole host of problems treated by family therapy. This section covers the following topics: psychosomatic and medical conditions, alcoholism, anorexia nervosa, drug abuse, and placement prevention. The final chapter provides an opportunity for us to take an overview of the matters we have discussed throughout this volume and offer our thoughts on future directions for outcome studies. Our hope is that this book will be especially useful for practitioners and students of family therapy. Our goal is to bridge the gap between practitioners and researchers and heighten practitioners' awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of this method of treatment. We do so in the belief that family therapy should not be just theory driven, and practitioners should have empirical support for what they do. Researchers may find the book useful as a source of reference. We have tried to keep to a minimum the use of research jargon and write in plain English to make the information more accessible to nonresearchers. We received a grant to support our research for this book from the office of Dr Terence Hogan, Vice-President of Research, University of Manitoba. Dean Harry Specht and Professor Richard Barth at the School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley, made it possible for H.F. to complete portions of this book while enjoying Berkeley as a visiting scholar. They have our deep appreciation. Ms. Sharon Tully, librarian at the University of Manitoba, conducted much of the literature search for this project. This was a very complex and time-consuming process, and we thank her for her understanding and infinite patience. Our friends Brian Minty of the Department of Psychiatry, University of Manchester, England, Diane Hiebert-Murphy of the Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba, and Richard Barth, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley, read parts of the manuscript and gave us valuable advice, and we thank them for their support. Margaret Roy read the manuscript and gave us the benefit of her wisdom. We reserve our deepest gratitude for the students and clients we have had the privilege of working with for something like thirty-five years between the two ofus, who compel us to examine and re-examine what we know, and who, in the final analysis, are our best teachers. This book is dedicated to them. This book would not have been possible without the unfailing support of our families. R.R.'s two children are grown up and have their

Preface xv own homes; his wife Margaret was, as with all his projects, his principal adviser. Sandra, Julian, and Jessie patiently (mostly) allowed H.F. the time to work on this project, even when perhaps his attentions should have been focused on other pursuits. We would like to express our deep gratitude to Professor Nathan B. Epstein, who counts among the pioneers of family therapy, for agreeing to write the Foreword. This is especially gratifying for R.R. who had the privilege of being a member of Professor Epstein's Department at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. Professor Epstein was the founding Head of the Department of Psychiatry at McMaster University. Finally, it will be a gross oversight ifwe failed to express our gratitude to Virgil Duff, Executive Editor of the University of Toronto Press, whose friendship, advice, and guidance in this and previous projects have proved to be invaluable.

HOW GOOD IS FAMILY THERAPY?

I

Family Therapy: An Overview

Family therapy is a widely used method of psychotherapy that has gained enormous popularity over the past two decades or so. It is not that working with families was unknown among professional mental health workers before the emergence of systems-based family therapy. Social work has a time-honoured tradition of making the family and its environment the focus of intervention (Broderick and Schrader 1992). The new element introduced by the 'pioneers' of the family therapy field was a radically new theory of etiology to interpret and treat psychological, psychiatric, and interpersonal problems. Simply put, the contention was that symptoms were the products of family dysfunction in one way or another, and, therefore, intervention had to be with the family rather than the symptom carrier alone. The other radical departure lay in the rejection of a Cartesian formulation of a reductionistic (linear cause-effect) approach to science. Systems theory, at the heart of which is circular rather than linear causality, is the scientific underpinning of family therapy. The definition of system most widely accepted is Miller's (1965) : a system is a series of elements organized in enduring and consistent relationship with each other. Steinglass, after a thorough analysis of the pros and cons of the relevance of systems theory to family therapy, concluded that 'in the end, researchers and clinicians work with families because they believe that these naturally occurring behavioural systems cannot be ignored. Families clearly fit the most popular working definition of a system - even if, at times, it is hard to identify all the units that should be included within a particular family' (1987: 32). Wynne (1988) put forth a somewhat different view on the question of the application of 'systems' to family. He acknowledged the viability of

4 How Good Is Family Therapy? the concept, but added that 'a great deal of conceptual clarification was still needed. Systems concepts have all too often been used so carelessly that communication among theorists, clinicians, and researchers has been seriously impaired'(1988: 270). Furthermore, in the same vein as Dell (1986), who noted that 'clinicians know (experientially) that A does lead to B: that mothers do control families and Dr. Minuchin does change families, ' Wynne articulated the problems inherent in the notion of circularity, especially from a research point of view. His main objection to blind adherence to circular causality arose from the recognition that it ignored the 'time line' factor, 'which prevents truly circular processes from ever occurring' (ibid.: 271). Wynne's observations are of great import for researchers who struggle with methods that may truly incorporate 'circular' causality and, in the main, find the task hazardous and elusive. The major ramification for adopting the systems perspective was that without the focus on cause and effect (dependent and independent variables) new research methodologies had to be found to explain the symptomatic behaviour in the context of a 'circular' pattern of interaction between family members that created and maintained such behaviours. The conceptualization of psychosomatic families by Minuchin, Rosman, and Baker (1978) is an example of such a methodology, which continues to come under the close scrutiny ofresearchers (it is noteworthy, however, that Minuchin is directive and lineal in therapeutic situations and seemingly effective). Second, the relevance of applying traditional research tools to evaluate the outcome of treatment (family therapy) had to be re-examined. The debate that surrounds the selection of appropriate statistical techniques to assess outcome, which will be discussed presently, is furious indeed. These two issues continue to draw much attention from family therapy researchers. While researchers continue to struggle with these highly critical issues, practitioners remain mainly unconcerned. Complex reasons account for their indifference. Family therapy in this respect shares the same reality with psychoanalyses from another era. Practitioners have historically demonstrated a propensity for 'buying' into new and innovative methods of understanding and resolving psychological and psychiatric maladies. This led the British sociologist Paul Halmos (1965) and American psychiatrist Jerome Frank (1979) to observe that psychotherapists tended to operate on unshakeable faith. They believed in the infallibility of their approach. The foundation of their

Family Therapy: An Overview 5 faith was rooted in their unconditional acceptance of the words and preaching of their 'gurus.' Family therapy is no exception to that phenomenon, but is it where it stands? Werry (1989), in a somewhat overstated case against family therapy, proclaimed family therapy 'as a rather sad sack relying for its status largely on assertion, selfcongratulation, guruism and denigration of alternatives. Like psychoanalysis, family therapy resembles a religion rather than a proper professional endeavour.' This is an ungenerous view of the current state of family therapy research, but Werry's scepticism is not entirely devoid of merit. Family therapy establishments conduct 'master' classes, the purpose of which is to impress the novice and the believers with the 'dazzling moves' and use of 'incredible metaphors' by the 'masters.' This kind of activity more appropriately belongs in the arena of the performing arts than as a treatment method rooted in the scientific assumptions of systems theory. Werry, however, commits the common error of taking a static view of the field. Indeed, family therapy has its share of 'fathers and mothers.' Their task was to develop and propagate a radically new way of therapy, which they achieved with incredible success. The task of the next generation of researchers (believers and non-believers alike) and practitioners is to begin to ask the hard questions about why family therapy works and how effective it is. As this book purports to demonstrate, such questions are being asked with increasing regularity. The question of etiology (which is somewhat outside the scope of this book) in family therapy has been ' resolved' by assigning low priority to it (Roy 1987). Questions, however, persist. Is circular etiology (note that the term 'circularity' has given way to 'recursive' by some) subject to disconfirmation? What constitutes a family? Who is to be included and who is to be left out of therapy? How definable an act is family therapy? Several schools of therapy have emerged. Is one school superior to another? How much of family therapy is 'art' and how much is science? What is to be considered a favourable outcome, removal of the symptom, which curiously resurrects the question of etiology, or 'improved' family functioning, or both? What are the selection criteria for family therapy, or is it more of a panacea for all conditions ranging from childhood asthma to chronic pain to drug addiction to suicidal adolescents to physical and sexual abuse of women and children? If the scientific underpinning for family therapy is systemic, should other systems (besides the family) be included in treatment and, hence, in measuring outcome? How critical are therapist-related

6 How Good Is Family Therapy? variables in outcome research? How does family therapy compare with other psychotherapies or pharmacotherapy in certain disorders? In the remainder of the chapter we examine the conclusions of some of the major reviews of family therapy outcome research. Conceptual and methodological problems as well as omissions identified by the reviewers themselves will be highlighted. Against that broad background, the rest of the book will consider the current state of outcome research in selected areas. Models of Family Therapy- Myth or Reality

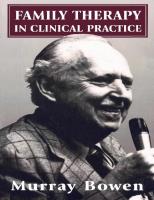

The late 1960s and 1970s witnessed an enormous proliferation of schools of family therapy. Indeed, history may judge those years as the heyday of family therapy, when the field was crowded with innovators, who each created their own particular brand of family therapy. Bowen, Haley, Minuchin, Palazzoli, and others laid claims to their version of family therapy. Those differing approaches became the 'schools' and 'models' within their own training programs and created legions of strict adherents. Minuchin (1982), in his autobiographical ruminations, described this era as one of building castles by family therapists. But maintaining the castles was proving too expensive, and soon they would be empty, he concluded. In the meantime, schools are merging and eclecticism and common sense is replacing, albeit slowly and grudgingly, rigid subscription to this school or that. Minuchin's structural and Haley's strategic schools probably gained more popularity than all the others. How similar or different are these schools? This is an important research question because of the rigour necessary to operationally define family therapy. Are these two schools totally differentiated, or are there important theoretical commonalities? Are the differences merely in appearances, or are they substantive? ls it possible, in practice, to be strictly one or the other, or is it even desirable? To pursue the question of the operational definition(s) used by researchers, we shall examine the review literature on family therapy outcome to gain a broad understanding of how this thorny issue has been tackled. In their most exhaustive review, Gurman and Kniskern (1978) made an interesting and meaningful distinction between behavioural and non-behavioural methods of marital therapy. It is an interesting distinction, as it provides a simple way of grouping divergent nonbehavioural methods. It should be noted, however, that most non-

Family Therapy: An Overview 7 behavioural family and couple therapies are directive as opposed to non-directive, and behavioural techniques are embedded in them. In a subsequent article, Gurman (1988) noted that 'there is a strong movement afoot in the family therapy field toward integration and rapprochement.' Some of the common 'ingredients' shared generally by the field of family therapy, he noted, were: (1) The process of reframing, whereby the presenting individual problem is reframed in the systemic context; (2) focus on communication; (3) alternative modes of problem solving; (4) modification of hierarchical incongruities and generational boundaries; and (5) modification of aversive interpersonal behaviours. In short, at least at the conceptual level, the divergent methods of family therapy shared some common elements. These methods employed very similar therapeutic (direct and indirect) moves and defined therapeutic success in identical terms. DeWitt (1978) resolved the dilemma of divergent techniques by drawing a distinction between conjoint and non-conjoint family therapy in her review of four previously published reviews of family therapy outcome studies. Conjoint family therapy meant that 'all relevant members of the family must have been treated together as a unit for all or major portion of treatment.' This tendency to group together under a broad rubric various 'schools' or 'models' of family therapy found justification in a review of ten previous reviews of family therapy outcome literature by Hazelrigg, Harris, and Boruin (1987). The basis of their argument was that despite differences between schools, family therapies were rooted in systems theory (which is at the heart of Gurman's viewpoint) and defined measures of successful outcome in a relatively uniform way. Hence, they argued that 'there is common ground that justifies combining the results of studies from different perspectives ... The methods of intervening may differ among family therapists, but the overall goal is one of systemic change' (ibid.: 430). In fact, these authors did not provide any information about the different methods of family therapy employed by researchers. Russell and her colleagues (1983), in reviewing family therapy outcome studies, did not directly raise the question of the divergent family therapy techniques, but addressed a very fundamental problem, namely, that regardless of the school, the goal of treatment was the removal of the presenting problem at the expense of correcting faulty family dynamics. The point of note is that outcome measure(s) was independent of the models or schools of family therapy, again provid-

8 How Good Is Family Therapy? ing a common ground for the varied schools. Epstein and Volk (1981), in an otherwise excellent review of outcomes of psychotherapy, repeated the distinction drawn by Gurman and Kniskem (1978) between behavioural and non-behavioural family therapies. All 'nonbehavioural' family therapies were assumed (since the point was not made) to encompass the same, if not, similar processes. LeBow (1981) took exception to the trend and stated that 'most of the outcome literature, however, has failed to discriminate between family therapy approaches.' He was unconvinced that Bowen's, Haley's, Guerney's, and Whittaker's approaches could be generalized as a single approach. Epstein (1988), in contrast to his earlier opinion, echoed Lebow's objection and stated that 'the most immediate priority is the development of rigorous, highly specific, and operationalized methods of family therapy' (ibid.: 121). Even the early reviewers were conscious of the challenge posed by different approaches of family therapy and established arbitrary definitions for the purpose of the review (Wells, Dilkes, and Trivelli 1972). Wells and Dezen (1978) acknowledged a marked increase in the number of outcome research studies between their two reviews, but their concern that 'schools' of family therapy could not be described as 'an entity' persisted. Wynne (1988) furthered the viewpoint (discounting Lebow's and Epstein's objection) of many reviewers by claiming that family therapy was more than a 'modality.' In fact, it was an approach to gather and organize information to determine and apply intervention in the context of the family system. Modalities in themselves were not as important as the theoretical underpinning upon which the models rested. The systems approach made the schools more similar than disparate, and, hence, in research the actual model of therapy was not as relevant as its scientific root(s). Family therapy is perhaps moving in the direction of uniformity, away from its exciting and multiple orientations. Or, is it possible that the distinctions between the models, only possible at a high level of abstraction, cannot be readily translated into operational terms, and, thus, some sort of methodological compromise is unavoidable? Difficulties associated with treatment variables were outlined by Guerney (1985), who noted that factors such as one family therapy versus multiple-family therapy, limited number of sessions versus openended treatment, marathon versus fifty-minute sessions, and, Guerney might have added, one model of family therapy vs another presented enormous challenges to the researchers.

Family Therapy: An Overview 9 As will become evident in the course of this book, researchers continue to employ and test the efficacy of specific methods of family therapy and compare the relative merit of different schools. Clinicians continue to promote and refine their particular schools and methods of family therapy, as a quick glance at the latest edition of the Handbook of Family Therapy will bear out (Gurman and Kniskern 1992). In their comprehensive review Gurman, Kniskern, and Pinsoff (1986) identified a clear trend towards, what they described as, theoretical and technical integration. Yet, they noted an absence of research on such integrative models. Their review is unusual in the sense that they examined the relative merit of 'schools' of family therapy to treat a variety of disorders. Any systematic drive towards integration of divergent methods of family therapy is still in its infancy. Nevertheless, wisdom gleaned from practice suggests that even the purists, in reality, tend to be eclectic and do whatever is in the best interests of the client-system. At an annual meeting of the American Association of Family Therapists, someone noted that Minuchin had made a paradoxical intervention in his live case demonstration, clearly a 'strategic' move, not usually associated with his structural school. Minuchin's response was characteristically unequivocal. In essence, he said, 'Use whatever works.' Kolevzon and Green (1983), in their analysis of models of family therapy, asked, 'How different are, in fact, these models of therapy in their actual practice? More important, are the differences between these models better predictors of therapeutic effectiveness than are the similarities?' (ibid.: 164). Reviews of outcome studies to date provide a partial answer to the first question, that is, researchers have found justification on conceptual grounds for adopting an integrative view. Epstein's (1988: 120) definition of family therapy is worth quoting as it offers a way of linking seemingly varied approaches to family therapy: family therapy is 'a therapeutic approach to working with the family as a system for the purpose of aiding the family members to achieve solutions to problems that interfere with their satisfactory functioning as individuals and as a family unit.' Again, subscription to the notion of the family as a'system' is the unifying theme. Outcome Measures

Family therapy outcome research has had special difficulty in defining and therefore measuring outcome. This problem has many sources,

10 How Good Is Family Therapy? the principal one being the opposition or reluctance to use traditional and therefore reductionistic measures of outcome. Symptom removal which is inevitably individually focused (Epstein resolves this problem by incorporating satisfactory function of the individual in his definition of family therapy), while the avowed measure of success in several of the therapeutic models of family therapy, raises the ire of many for the narrowness of the outcome measure(s). On the other hand, if families seek help with this problem or that, resolution of that problem, be it ketoacidosis for diabetic children or an alcoholic husband, is precisely what the families desire. This focus on symptom removal, in the minds of many, undermines the key objective of family therapy which is to rectify the dysfunctional relationships in a family system. Russell and her colleagues (1983), for example, were critical of Minuchin and his colleagues' choice of outcome measure in their investigation and treatment of anorectic families. Their main objection was that the researchers failed to report 'interaction within marital, parental, and sibling subsystems after therapy.' How valid is this criticism? The central point is that without these changes, improvements they chose to report presumably could not have happened. The issue is one of detail, because the therapy is predicated on a particular theory of etiology. In Minuchin's case the family attributes of psychosomatic families and physiological vulnerability of the identified patient, and remission or eradication of symptoms can only occur when the relationship issues have been successfully treated. Whether one chooses to re"port them is a moot issue. Jacobson (1988), while agreeing that multiple measures must be used in family therapy outcome research, finds himself in agreement with the view that 'ultimately a successful outcome means that the presenting (or emergent problem) has been eliminated' (ibid.: 153). He contends that 'changes in family interaction are often the hypothesised means whereby the family therapist proposes to solve the problems that brought the family in' (ibid.) . He goes further when he states that 'except in those instances where dysfunctional family interaction is the presenting problem, measures of family interaction are at best indirect measures of treatment outcome' (ibid.). The means and the ends are not to be confused. In keeping with Jacobson's proposition, Olson (1988) proposed multiple-level goals for second order change determined by the nature of the presenting problem. For an individual psychiatric symptom, the desirable change is elimination of the symptom. In contrast, for a family

Family Therapy: An Overview 11 confronted with family and extended family issues, the goal of treatment is changing the type of family system. The solution offered by Olson as well as Jacobson is unsatisfactory to many because of the prevailing view that a symptom is not a symptom, but a mere outward sign of deeper family conflicts. Guerney (1985), for example, preferred a very inclusive set of outcome variables that would include symptom eradication and factors such as adequacy of communication, distribution and mechanism of power, and adequacy of family conflict resolution. We shall now briefly examine the measures of outcome as reported by reviewers of outcome studies in family therapy. Hazelrigg, Harris, and Boruin (1987) identified several problems with outcome measures (dependent variables) in their very careful analysis of outcome studies. The concept of change, they contended, was often narrowly based on measures such as parent ratings of patient behaviour or experimenter ratings of patient behaviour or recividism. They felt that 'considerable progress could be made in evaluating family therapies through the increased use of multiple change indices.' They believed that broadly based measures by ensuring overlap would facilitate comparison between studies. The problem is not just one of overinclusiveness of outcome measures, but rather some agreement among researchers and clinicians about what constitutes 'success' in family therapy. Wells, Dilkes, and Trivelli (1972) divided their review of outcome studies into inadequate, borderline, and adequate based on some methodological considerations. Only two studies met their criteria of adequate (inclusion of control group and specifit outcome measures). They were impressed by the outcome measures employed by the investigators who included hospitalization rates and days lost for functioning for psychiatric patients following crisis-oriented family therapy. These outcome measures were patient focused. In fifteen studies that were deemed inadequate, outcome measures, in the main, were self-reports by clients and therapist evaluation. To what extent outcome measures have been refined might be assessed by a review conducted by Wells and Dezen (1978) several years later. The 1978 review covered the period between 1950 and 1970. The 1978 review was for the six-year period 1971 to 1976, and it examined uncontrolled reports, comparisons between treatment and no treatment, and comparisons between alternative treatments. Some of the old criticisms were still applicable to the uncontrolled studies, such as poorly defined outcome measures. However, a few uncontrolled studies - for example, Minuchin and his associates' study of psychoso-

12 How Good Is Family Therapy? matic families and a report from the McMaster group - despite lack of controls, were better designed as multiple and standard measures were used to assess outcome, a phenomenon almost totally absent in the 1972 review. Wells and Dezen (1978) found nine studies in the category of treatment versus no treatment and seventeen studies comparing family therapy with alternative treatments. These studies were clear signs of significant improvements in the methodology of outcome research. The outcome measures included pre-post measures of family functioning; improvement in presenting symptoms; improvement ratings by therapists, mothers, and independent clinicians; and the follow-up rate of recividism. In short, despite persisting methodological shortcomings, significant progress in refining outcome measures was evident in the early 1970s. DeWitt (1978) combined the results of four previous reviews of family therapy outcome studies and added studies that had been missed by previous reviewers. While a wide variety of outcome measures were used in the studies reviewed by DeWitt, she remained concerned that too much attention was paid to the characteristics of the identified patient and not enough to those of the family. Studies that investigated treatment efficacy in making changes at the level of the family system did not always purport to measure such changes. In other respects, DeWitt's conclusions about the continuing problems in measuring outcome were not much different from Wells and Dezen's. In a very thoughtful analysis of methodological problems confronting outcome research in family therapy, Lebow (1981) concluded that the adoption of widely accepted packages (for evaluation of outcome) was not very likely in the immediate future, yet some corrective measures could be taken to deal with some of the glaring gaps. For instance, Lebow advocated use of multiple perspectives and multiple criteria by which to assess change: 'In a thorough assessment, some measures should be included from all three perspectives (patient, therapist, rater), and measures should focus upon multiple aspects of change at both the identified patient and the system level.' The more standardized the measures are, the more feasible it is to conduct comparisons between studies. In assessing outcome Lebow emphasized the timing aspect of follow-up assessment, as many short-term gains may not last or effects of treatment may reveal themselves only after some time. His main criticism was that follow-up periods had been very short.

Family Therapy: An Overview 13 Russell and her associates (1983) also expressed dissatisfaction with the focus of the outcome research being on removal of presenting symptoms. They bemoaned the fact that 'few research teams have gone beyond the traditional focus on presenting problems to link system dynamics to treatment goals and subsequent outcome.' Their suggestions for improving the quality of research were in line with Lebow's. They proposed a single-case design with each family serving as its own control and repeated measures of family interaction which would eliminate some of the problems of traditional pre-post design. In essence, however, Russell and associates were proposing that outcome had to be examined in the context of the family rather than the individual's symptoms. As was noted earlier, these two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Hazelrigg, Harris, and Borduin (1987) departed from the traditional approach to literature review and conducted an integrated statistical analysis of outcome studies in family therapy. Their findings confirmed some of the observations of earlier reviewers that in the first place outcome tended to be measured on some narrow parameters such as recidivism or experimenter ratings of patient behaviour, and, second, that use of multiple change indices was overdue. They found that only eight studies out of twenty included in their review used multiple measures. They reiterated the point made by others that without the benefit of multiple indices, comparisons between studies would remain onerous tasks. There appears to be some degree of agreement among the reviewers that the measures of outcome of family therapy, while gaining sophistication over time, remain problematic. The narrowness of outcome measures is a constant theme in almost all the reviews. The argument in favour of multiple indices for measuring change emanates from several sources. One is ideological, namely, that without the benefit of the measures for changes at the systemic level, and not just at the level of the identified patient, there is the ever present risk of betraying the systemic orientation of family therapy, a view that is at variance with that of Wynne, Jacobson, and Olson. Second, on a more positive note, multiple measures and packages of standardized instruments would facilitate more meaningful comparisons of outcome in family therapy. Reviewers seem to suggest, without resorting to categorical statements, that many researchers in the field continue to experience incongruity between the goals of their investigations and the tools they use to measure outcome.

14 How Good Is Family Therapy? Therapist Variables

The centrality of therapist variables was noted by Gurman and Kniskern (1981) now over a decade ago. How much attention and what kind of consideration has this factor received in outcome assessments of family therapy? • Measuring the impact of therapist characteristics remains severely neglected in family therapy outcome research. Epstein (1988) proposed that only the most highly trained therapists should participate in outcome studies, as that will maximize the probability of positive outcome. Jacobson (1988) had a different view on the value of 'experience' and level of training, as he contended that 'although it would be nice if clinical experience were directly related to positive outcome, it is an important but empirical question that can only be answered by directly comparing experienced and inexperienced therapists in the same studies' (ibid.: 151). Furthermore, Jacobson (1988) stated that on the basis of very limited empirical evidence in marital therapy, the hypothesis that experienced therapists produced better results was, at best, equivocal. We now examine whether and how much our reviewers paid attention to the question of therapist variables. Gurman and Kniskern (1978), in the most exhaustive review of the time, found that the key therapist variables that had positive association with outcome were the capacity to build and maintain relationships and male gender. Epstein (1988) in his enumeration of criteria for good outcome research in psychotherapy identified the requirement that the therapist be trained in the appropriate model being investigated, but they were silent on other attributes of the therapists. In Wells's two reviews (1972, 1978) the term 'therapist variables' did not appear for the reason that these variables were, in the main, ignored by researchers. This omission was not lost on Gurman and Kniskern (1978), who in a measured criticism of Wells's 1978 review noted that 'there are many family therapists, we among them, who believe, on clinical grounds, that therapist variables are at least as salient as technique variables.' They supported their belief by pointing out 'the growing body of empirical literature.' Despite their claim of a growing body of literature, the therapist variables continue to receive, at best, scanty attention from researchers. For instance, Russell et al. (1983) and Hazelrigg, Harris, and Borduin (1987) ignored this variable in their otherwise important reviews. This point was not lost on DeWitt

Family Therapy: An Overview

15

(1978). She stated that 'only minimal information is available on the characteristics of the therapists who participated in the conjoint family therapy reported in the studies reported here.' The simple truth is that the studies she reviewed did not generally consider the therapist variables of sufficient significance to merit analysis. Lebow (1981) recognized that in the broader psychotherapy literature the significance of the therapist variables in outcome research was gaining increasing prominence. He noted that factors such as the therapist's level of experience, age, sex, race, and relationship skills have been examined by researchers. In family therapy, he noted, existing data provided limited support for the proposition that more empathic therapists experienced more success. However, Lebow urged that future outcome research should make a more determined effort to delineate the significance of therapist variables. Jacobson's (1988) observations about the difficulties associated with treating 'therapists' as a 'randomized factor' demand attention from researchers. He acknowledged that he had no easy solution to this dilemma. He suggested that 'intramodel comparisons and studies conducted with relatively inexperienced therapists may lend themselves to using the 'therapist' as a between-subject factor, while intermodal comparisons with seasoned therapists may require adherence to current conventional wisdom' (ibid.: 152). In the course of our review, we explore the acceptance of Jacobson's proposition as well as the rigour that researchers have applied to the question of therapist variables.

Data Analysis

Dissatisfaction with statistical methods employed for data analysis is not hard to detect. The criticisms range from absence of any meaningful analysis to the use of inappropriate statistics, absence of descriptive statistics other than group means and standard deviation, and heavy reliance on statistical significance Uacobson 1988). Gurman and Knis kern also observed that 'evidence beyond the statistical significance of changes in group means of the clinical importance of changes achieved by families and individual family members' is necessary (1981: 770-1). For the outcome data to be meaningful, it is important that standard deviations of the change measure(s) used and the frequency distribution of the actual number of improved cases be reported.

16

How Good ls Family Therapy?

This issue has been further complicated by questions about the relevance of conventional analysis, mainly designed to explore linear associations, to situations where there is at least a debate about the absence of such relationships (Steir 1988). Pinsoff noted that 'a correlational analysis is not designed to elucidate non-linear relationship' (1988: 166) and proposed the use of a multivariate correlational strategy which permits the application of multiple regression to assess the 'extent to which combinations of variables, as opposed to single variables, predict outcome' (ibid.: 166). Some of the reviews examined here simply did not address the q uestion of data analysis. Epstein and Volk (1981), for example, recommended that 'adequate size of research sample [be] used. Statistical expertise is now a necessary component of all modem research groups.' In Wells's two reviews (Wells, Dilkes, and Trivelli 1972; Wells and Dezen 1978) problems associated with data analysis were not mentioned. The use of appropriate statistics to measure outcome was not discussed by DeWitt (1978) or Russell et al. (1983) either. LeBow (1981) urged the use of stepwise and multivariate models. Hazelrigg; Harris, and Borduin (1987) reported on the kind of statistical analysis employed by some of the researchers, but they did not provide a critique. They bemoaned the fact that statistical analyses performed my many researchers were not adequately reported. This oversight by the reviewers, who were very focused on the methodological shortcomings of the many studies they reviewed, is not easily explained. Gurman, Kniskern, and Pinsoff (1986) uncovered a conspicuous absence of descriptive statistics in reporting analysis of results. Nevertheless, this omission may reflect the current state of research in family therapy, namely, more immediate and fundamental methodological issues (to be examined in the rest of the book) demand attention, and, mistakenly, the precision with which data analysis needs to be dealt is relegated to a low level of priority. Key Conclusions of the Reviews

Despite all the major methodological shortcomings (including lack of control groups, small and ill-defined samples, lack of attention to therapist variables, inadequate instrumentation, poorly defined outcome measures, confusion over dependent and independent variables, multitude of outcome measures, problems of operational

Family Therapy: An Overview 17 definition of family treatments, and inappropriate and inadequate data analysis) of family therapy outcome research, the consensus among reviewers is that family therapy, with some qualifications, works. Wells, Dilkes, and Trivelli (1972) estimated, based on six uncontrolled studies, that combining the outcomes improvement and some improvement 69 per cent was the overall rate of success for family therapy with adults. With children the rate was 79 per cent. These authors were impressed by the paucity of adequate research design and the glaring omission in family therapy research of control groups, as well as several other methodological limitations. Wells and Dezen (1978) were basically unimpressed in their subsequent review. Only in uncontrolled single-group studies was positive outcome evident. Controlled and comparative studies, in the main, were found equivalent with non-formal and alternative treatments. The authors, however, remained sceptical. They noted that 'numerous methodological and practical difficulties beset the current body of family therapy research.' DeWitt (1978) came to similar conclusions as Wells and Dezen (1978) in that out of thirty-one studies they reviewed, twenty-three uncontrolled studies reported results that were similar to non-conjoint methods, and in the remaining studies, each with a comparison group, five were superior to there being no treatment. DeWitt was almost apologetic for the unimpressive results and pleaded that methodological deficits in almost all the studies could be explained on the basis that the research in this area was just beginning. Gurman and Kniskern (1981) repeated their calculation from a previous review (1978) of positive outcome for 73 per cent of family cases and 65 per cent of marital cases. They adopted a rather generous attitude towards flawed methodology (while at all times acknowledging such flaws), claiming that while methodological problems facing family therapy outcome research were serious, indeed, they went on to say, 'Nevertheless, we believe that, like love, methodological adequacy is not enough.' Prima facie, the association between love and research methods may not be self-evident, the point being love is not always 'logical' nor is it that love alone is enough. Thus, they invoked the notion of 'logical adequacy' to justify their conclusion that the results of poorly designed studies 'are entirely consistent with those of better quality' (1981: 752), and on that basis they posited an optimistic and perhaps exaggerated view of the efficacy of family therapy. Minimally, their ambivalence about methodological rigour (despite their claim to

18 How Good Is Family Therapy? the contrary) runs the risk of contributing to the family therapist's scanty regard for outcome research. Would they have found the same justification for flawed research design if the findings of these studies were unfavourable to family therapy? Gurman, Kniskern, and Pinsoff (1986) found much to praise in the state of outcome research in family therapy. They were rather noncritical of the research methods adopted by many of the studies, which led Raffa, Sypek, and Vogel (1990) to write that 'the reviews by Gurman and colleagues are scholarly, well reasoned, well written, and the most comprehensive in the marital and family literature. We do not believe, however, that they would convince anyone not already convinced of the 'efficacy' of family and marital therapy, given the methodological flaws in the studies as, for example, the general failure to employ control groups.' Russell and her colleagues (1983) also assumed a very uncritical stance of the research methodology in reporting the outcome of various studies related to alcoholism, drug abuse, juvenile offences, and a variety of childhood problems. Measuring outcome in terms of resolution of the presenting problems (used by the majority of the studies reviewed by them) rather than altering systems dynamics was at the heart of their criticism. They proposed, in agreement with Gurman and Kniskern, that 'much can be learned by considering the trends that appear across all imperfect projects.' There is no clear way of judging the extent to which statements of that kind may have hindered methodological advances in family therapy outcome research. Yet, these statements are there for anyone to see. The message seems to be 'if we cannot produce good research, let's make the most of bad research that seems to provide justification for our activities.' Hazelrigg, Harris, and Borduin (1987) reported the relative superiority of family therapy over situations of no therapy and alternative types of treatment. However, their conclusion was that the positive findings were tentative at best. They noted that most of the reports they reviewed involved families of children with behavioural problems despite the claim that family therapy was beneficial for nearly any client groups and that family therapies were 'slightly' superior to alternative treatments. It is noteworthy that only twenty out of 290 outcome studies met their criteria for inclusion which among other factors included a matched control group of either no treatment or alternative treatments. The other criteria included definition of a family as a minimum of a child and a parent, minimum of five families in each group,

Family Therapy: An Overview 19 complete reporting of statistical analyses and results, and the therapy process clearly meeting the definition of family therapy. Discussion This brief review is encouraging and discouraging. Indeed, the quality and quantity of research has improved significantly over the past two decades. Yet, there is considerable dismay expressed by many reviewers over the poor research design. The relative newness of the field of family therapy research was legitimately proffered by early reviewers as a viable reason for poor quality. Unfortunately, as recently as 1987 Hazelrigg and his associates resurrected the same reason in the face of almost insurmountable problems they faced trying to find a few studies that would meet the inclusion criteria of their review. Perhaps, time is upon us to look beyond the 'newness' issue. Raffa, Sypek, and Vogel (1990) have done just that. They summarized the criticisms of the outcome literature: (1) the paucity of controlled studies; (2) failure to describe the treatment techniques; (3) inadequate research design, beyond the issue on controls; (4) poor data analyses; (5) incongruity between treatment techniques employed and theoretical framework; (6) use of outcome measures lacking in reliability and validity; and (7) the total absence of effort to replicate positive outcome. This is a comprehensive list, but it fails to address the underlying reasons for the perpetuation of poor quality outcome research. The notion that somehow the uniqueness of family therapy has rendered the established methods of outcome research meaningless has, to some extent, contributed to sloppy designs, and the same reason may account for the publication of inadequate studies. Prominent investigators have found justification for poor research design and, as we pointed out, justified such research on rather questionable grounds. Raffa, Sypek, and Vogel (1990) did try to explain some of the shortcomings so commonly found in family outcome research. First, they claimed that the current state of the field of family therapy 'makes it impossible to construct meaningful control groups.' They attribute this difficulty to an absence of taxonomy for family pathology. In our view this is a serious problem, but not an insurmountable one. Minuchin's research on psychosomatic families, with a relatively precise description of family characteristics and very precise diagnosis, such as childhood asthma, makes it possible to establish adequate control groups for alternate treatments (since asthmatic children cannot be

20

How Good Is Family Therapy?

left untreated); we shall examine this question fully in a subsequent chapter. While the question of 'controls' is a serious omission, there are other equally serious problems. To pursue those questions we turn to Wynne (1988), who edited a volume based on the reports presented at a joint meeting of Family Process and the National Institute of Mental Health, in the United States. The scope of the research problems related to outcome research in family therapy was very substantial. That seemed to be the general sentiment of the participants in that conference. The catalogue of methodological problems recognized by the early critics was still to be easily found in much of current outcome literature. Family therapy outcome research has been beset by real and imagined issues, the central one being the relevance of established research methods to family therapy research. That is no excuse for a plethora of poor quality research which is the halhnark of much of family therapy outcome research. The point is that in the name of inapplicability of existing methods, great deficiencies have crept into the design of family research studies. Attention to simple design issues such as the clear establishment of dependent variables, definition of independent variables with some degree of clarity, careful instrumentation, control and comparison groups, and appropriate data analysis would vastly improve the quality of research and in the process reveal the shortcomings of conventional methods when applied to family therapy. The point is that to date relatively few studies are sound, judged against the criteria of existing methodology. In other words, the usefulness of current research techniques has been, to some extent, prejudged. In essence, the participants of that conference expressed collective concern with the state of family therapy outcome research and began the hard process of searching for solutions. Conclusion

Our effort in this chapter has been to paint the field with a broad brush. To that end we used, in the main, reports of reviews in family therapy outcome research. There is little doubt that the sheer volume of such research has increased at a phenomenal rate since the early 1970s. The quality has improved, but not nearly as phenomenally. There are early signs that resolution to some of the problems is in sight, problems such as grouping together a variety of schools and models of family therapy, tailoring outcome to the nature of the difficulties, using multiple mea-

Family Therapy: An Overview 21 sures, increasing use of control groups, and improved techniques of data analysis. There is also an emerging consensus that while the findings are encouraging, and indeed very promising in some instances, rigorous methodology must be applied if family therapy is to go beyond the stage of being a mere act of faith.

2

Children and Family Therapy

The child guidance movement in the United Kingdom and the United States was the precursor to family therapy. Ever since Freud there has been a rising awareness and mounting knowledge that children's emotional and psychological problems are deeply rooted in their relationship with their parents in general and mothers in particular. The mother-child relationship, from Sigmund Freud to Michael Rutter, has been at the centre of research and clinical exploration to explain childhood emotional problems. Systemic family therapy has extended the focus on the mother-child dyad to include all intimates in the lives of children. Logic would dictate that a family-based approach to treat children's psychological and emotional problems would be superior to any other types of treatment. In this chapter we explore the success of family therapy in reducing or ameliorating emotional conflicts and their behavioural manifestations in children. The effectiveness of family therapy with children has come under periodic review; it should be noted that we cover some of this literature under specific topics, such as psychosomatic problems in children (Chapter 5). Masten (1979) in her review concluded that 'there are major shortcomings in most of the available data, with only two well-controlled studies [in our judgment these two studies were far from well controlled). If the value of family therapy as a treatment alternative or, ideally, as the treatment of choice for a referred individual child is to be established, more and better controlled comparative outcome studies will be necessary.' Kirkby and Smyrnios (1990) reached a similar conclusion. They observed that 'carefully designed studies of psychotherapy with children and families are rare.' This is despite the fact that they .based their review on nine studies that

Children and Family Therapy 23 compared brief family therapy with an alternative method of intervention. We have excluded parent training type programs from our review. That topic merits consideration on its own. A sample of early studies, studies with patients on a waiting list or with no treatment groups as controls, and studies comparing family therapy with other methods of intervention are the focus for this chapter.

Early Studies In 1967 Martin discussed four cases. This study was very much in the nature of a pilot. Two 'experimental' families were compared with two cases on the waiting list. No formal comparisons were made and statistical analysis was altogether absent. Martin reported improvement in the children's school behaviour. The focus of intervention was to improve the family 's communication skills. This report was so preliminary that it would be best looked upon as a clinical report with a nominal evaluative component. In a retrospective study of thirty-five children, ten of whom were adolescents, fifteen retarded, and the remaining ten described as antisocial, Masters (1978) found that family therapy, by and large, proved ineffective. Seven of the ten families , despite careful screening, dropped out. Masters offered several reasons for the drop-out rate, one being the families ' poor socioeconomic status. Second, 'very poor interpersonal relationships proved a deterrent to the individual family members to cope with their problems in an open and objective manner.' Again, it would be erroneous to read more into this report than the experience of one practitioner. Santa-Barbara and associates (1979) reported a complex outcome study involving 279 families and eighty family therapists including staff and students. The average number of family sessions was six, ranging from two to thirteen or more. The children's problems were academic and/or behavioural, as identified by the family members. A battery of outcome measures was used to assess intellectual functioning, academic achievement, and disruptive school behaviour of the children. Studies of outcome at treatment closure showed that 79 per cent of families registered moderate or great improvement on the basis of therapist evaluation, but 45 per cent of families were rated as having a good or excellent prognosis. Seventy-six per cent of the families closed satisfactorily on the basis of the outcome measures. At the six-month

24

How Good Is Family Therapy?

follow-up 79 per cent of the subjects' original problems were better or much better. This was a complicated large-scale study, and, despite lack of a control group and a large number of therapists with varied levels of training, it was conducted with a great deal of care for methodological soundness. The results left little doubt about the benefit of treating the whole family in cases with children manifesting academic and/or behavioural problems. This study, at the very least, provided much incentive for the adoption of family therapy and was an early contrbution to family therapy outcome research. The final uncontrolled study we wish to report involved forty-three families with forty-five children who were involved in stealing (Seymour and Epston 1989). The families were seen an average of 3.3 times. A few of the children were in their teens, but over 80 per cent were under thirteen years. Outcome was assessed strictly on the basis of recurrence of stealing behaviour. At a two-month telephone follow-up interview by the therapist with a family member there were no instances of stealing in 54 per cent of the children. At the eight- to twelve-month follow-up that figure rose to 62 per cent; this information, too, was obtained by telephone from a family member. Seymour and Epston's study had several basic methodological problems. Families were not formally assessed for their functioning. Children were not assessed for their emotional or academic problems. The method of family therapy was not described, and therapy was conducted by the investigators. Outcome was reported in global terms, with no statistical analyses performed. Comments: It should be noted that some reports of family therapy with children are discussed in the chapter on family therapy with psychosomatic disorders. Dulcan (1984) and Smyrnios and Kirkby (1989) in their reviews of the family therapy literature included several reports of anecdotal accounts and uncontrolled studies of family therapy. The reports discussed in this section quite clearly convey the breadth of application of family therapy to treat children's problems. Despite the fact that the findings taken together were very encouraging, they did not truly reflect the efficacy of family therapy. Uncontrolled studies are, at best, suspect and at worst, misleading. Other than in the study by Santa-Barbara and colleagues, very meagre attention was given to even basic methodological considerations. Outcome measures were rarely objective. Therapy itself was often described in very general terms, and frequently the nature of involvement of the participants in

Children and Family Therapy 25 the therapeutic process was unclear. For the most part even rudimentary statistical analyses were absent. Under these conditions this group of uncontrolled reports were presumably biased and the findings somewhat overly optimistic. This last point receives much credence in the light of the findings of controlled studies. Nevertheless, these early uncontrolled reports probably contributed to greater use of family therapy with children and to vastly improved methods in future studies. Controlled Studies

Treatment versus No Treatment In the early literature controlled studies were virtually non-existent. Some were described as controlled, but fell far short of basic methodological requirements. The only study that compared family therapy with a no treatment group was that by Black and Urbanowicz (1987). They reported on thirty-eight bereaved children from twenty-one families who received family therapy in comparison with a no treatment control group of forty-five bereaved children from twenty-five families. Whether the groups were closely matched remained unclear because no statistical data were provided. At the time of bereavement the children were between the ages of under five years and twelve years or older. Outcome measures included parental depression and a variety of measures of the children's home and school behaviour as well as their health. Unfortunately, the measures used were not described by Black and Urbanowicz and were reported only in the follow-up data. Family therapy was provided by psychiatric social workers. Six therapy sessions were offered, spaced at two- to three-week intervals. The sessions took place at home two to three months after bereavement. The family therapy 'method' was not stated, although the description would suggest a systemic approach. Outcome at one year of follow-up, which involved twenty-one children, revealed that the treatment group did slightly better than the control group in terms of behaviour, mood, and health. At the two-year follow-up, which involved twenty-one children, the findings were in the same direction as earlier. The conclusion was that the treatment group had benefited from short-term family therapy. The major problem with the study was with the format of the report. While references were made to the Rutter A Scale, there was no men-

26

How Good ls Family Therapy?

tion of it in the text, let alone a description. Similarly, the method used to measure parental depression was not stated. The whole question of instrumentation was ignored, and family functioning issues were not addressed. The statistical analysis was kept to a minimum. For example, no attempt was made to locate the factors that could predict outcome, and there was no description of the statistical methods used for data analysis. This study had considerable scope, but through incomplete reporting and inadequate analysis its quality was compromised. Yet, the key finding was that family therapy with bereaved children was beneficial. This study lent support to the findings of the uncontrolled reports. The conclusion was that providing family therapy appears to be superior to doing nothing. In the following section the question of superiority of family therapy over other treatment methods will be examined. Family Therapy versus Other Treatments

Under this heading two main types of studies can be reported. First, comparative studies involving either structural family therapy (SFTl) or strategic family therapy (SFT2) versus another kind of therapy. Structural Family Therapy versus Other Treatments Ritterman (1978) conducted a complicated double-blind study, as her doctoral dissertation, to test the value of family therapy to treat hyperactivity in children. Forty children, with a confirmed diagnosis of hyperactivity and a mean age of eight years and four months were randomly assigned to four treatment conditions: (a) family therapy (based on a structural paradigm) alone; (b) combined family therapy and Ritalin; (c) family therapy and placebo; and (d) Ritalin alone. Children were given an exhaustive battery of pretreatment tests and the family completed a questionnaire devised for the study which was pretested for validity and reliability. Subjects in the treatment conditions involving family therapy received three sessions of family therapy over a maximum of seven weeks. As with all doctoral dissertations multiple analysis were conducted, but for the present purpose only the global findings are reported. Ritterman's central hypothesis that Ritalin alone would fail to produce a significant change on any single dimension of hyperactivity compared with the other treatment conditions was supported. As a result of a series of complex statistical analysis, several other conclu-