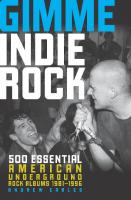

Gimme indie rock: 500 essential American underground rock albums 1981-1996 9780760346488, 9781627883, 0760346488

"Music journalist Andrew Earles provides a rundown of 500 landmark albums recorded and released by bands of the ind

1,765 118 7MB

English Pages 400 pages : illustrations ; 23 cm [403] Year 2014

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

100 Flowers --

Rutoclave 8 --

Babes in Toyland --

Bitch Magnet 20 --

Black Flag --

Butthole Surfers 38 --

Camper Van Beethoven --

Crayon 58 --

Dag Nasty --

Dwaaves 72 --

Earth --

Further 94 --

Galaxie 500 --

The Gun Club 122 --

Half Japanese --

Hüsker Dü 138 --

Jandek --

Lyres 156 --

Malignus Youth --

Minor Threat 182 --

Minutemen --

My Dad is Dead 198 --

Naked Raygun --

Opal 212 --

Pain Teens --

Pussy Galore 228 --

Rapeman --

Run Westy Run 250 --

Saccharine Trust --

Silver Jews 266 --

Sleater-Kinney --

Squirrel Bait 286 --

St. Johnny --

Swirlies 304 --

Tad --

TSDL 324 --

Ultra Vivid Scene --

Young Fresh Fellows 340.

Citation preview

500 ESSENTIAL AMERICAN UNDERGROUND ROCK ALBUMS 1981–1996

ANDREW EARLES

Dedicated to my life-partner in crime, Elizabeth Murphy, who’s truly responsible for this book . . .

First published in 2014 by Voyageur Press, an imprint of Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc., 400 First Avenue North, Suite 400, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA © 2014 Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc. Text © 2014 Andrew Earles All photographs are from the Voyageur Press collection. All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purposes of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or Publisher, who also disclaims any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details. We recognize, further, that some words, model names, and designations mentioned herein are the property of the trademark holder. We use them for identification purposes only. This is not an official publication. Voyageur Press titles are also available at discounts in bulk quantity for industrial or salespromotional use. For details write to Special Sales Manager at Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc., 400 First Avenue North, Suite 400, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA. To find out more about our books, visit us online at www.voyageurpress.com. ISBN: 978-0-7603-4648-8 Digital edition: 978-1-62788-379-5 Softcover edition: 978-0-76034-648-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Earles, Andrew, 1973– author. Gimme indie rock : 500 essential American underground rock albums 1981–1996 / by Andrew Earles. pages cm Summary: “Music journalist Andrew Earles provides a rundown of 500 landmark albums recorded and released by bands of the indie rock genre”—Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-0-7603-4648-8 (paperback) 1. Alternative rock music—United States—1981–1990—Discography. 2. Alternative rock music--United States—1991-2000—Discography. I. Title. ML156.4.R6E27 2014 781.660973—dc23 2014015967 Acquisitions Editor: Dennis Pernu Project Manager: Madeleine Vasaly Art Director: Cindy Samargia Laun Cover Designer: John Barnett Layout Designer: John Sticha Cover photo: © Jim Saah/www.jimsaah.com Printed in China 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 100 FLOWERS – AUTOCLAVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 BABES IN TOYLAND – BITCH MAGNET . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 BLACK FLAG – BUTTHOLE SURFERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38 CAMPER VAN BEETHOVEN – CRAYON . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58 DAG NASTY – DWARVES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 EARTH – FURTHER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94 GALAXIE 500 – THE GUN CLUB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 HALF JAPANESE – HÜSKER DÜ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138 JANDEK – LYRES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156 MALIGNUS YOUTH – MINOR THREAT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182 MINUTEMEN – MY DAD IS DEAD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198 NAKED RAYGUN – OPAL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212 PAIN TEENS – PUSSY GALORE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228 RAPEMAN – RUN WESTY RUN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250 SACCHARINE TRUST – SILVER JEWS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266 SLEATER-KINNEY – SQUIRREL BAIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 286 ST. JOHNNY – SWIRLIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 304 TAD – TSOL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324 ULTRA VIVID SCENE – YOUNG FRESH FELLOWS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 340 APPENDICES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 364 INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 384

INTRODUCTION THE INTENTIONS BEHIND THIS BOOK, HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF IT, AND OTHER (HOPEFULLY) HELPFUL POINTS

A

s I was writing these 500 entries, I regularly found myself removing fully formed statements and dumping them into another file that was saved as

“Bookintroductionandnotes.doc.” Before long, keeping this book’s introduction

under control loomed as an unwelcome challenge. Only so much context can be fleshed out across an entry-based survey of 500 albums, there’s only so much space with which

to provide that context, and there are better sources online and in book form (see below and in the appropriate section of the appendix) that will currently build, if combined, somewhat of a contextual narrative of America’s DIY/individualism/outsider/underground rock-based/experimental and so on . . . community (late ’70s to present day) The term “indie” has been used since at least the mid-’80s (mostly in the U.K. music press, at first) as a truncation of “independent” to describe the small labels that catered to the growing underground rock of the day. Eventually, that term begat “indie rock,” the more specific designator that rose up partly in reaction to the vagary of the term “alternative rock.” As if to confuse things, “indie rock” would eventually be attached to a set of bands with overlapping stylistic values, including Dinosaur Jr, Superchunk, Pavement, and Sebadoh. In other words, it came to be used to describe a subgenre as well as the larger genre that contained it, and during its heyday (see below), there were actual musical requirements that had to be met for a band to be considered indie rock. In the most simplistic terms, successful indie rock was often based on the application of grade-A pop hooks and melody to noisy, distorted guitar, aggressive, heavy or hardcore-tempo rhythms, and other sonic elements that might conflict with sonic beauty. But something else happened, too. Under the larger “indie rock” genre signifier, one could find a number of other subgenres—post hardcore, college rock, noise rock, lo-fi, emo, love rock, riot grrrl, proto-grunge/grunge, noise pop, shoegaze, left-field, outsider rock . . . the list goes on. It was in this loose framework that indie rock (the genre) and all its various subgenres (including, as somewhat confusingly revealed above, indie rock) experienced its heyday from roughly 1986 to 1996, give or take a year on either end. The pre-1986 albums discussed in the following pages would in some way or another influence the ’86–’96 titles. Also, as with the pre-1986 albums, there are quite a few ’86–’96 titles featured that no one in their right mind would call indie rock from a musical or aesthetic subgenre standpoint.

4 GIMME INDIE ROCK

These would be the albums by bands that operated on the periphery of the American indie rock genre (think opposite end of the spectrum from, say, Buffalo Tom) but appealed to its fans that nurtured more adventurous, demanding or wide-ranging tastes. Then there’s the handful of entries covering more mainstream alternative albums that have aged nicely and are worth reexamining. The lyrics to the song from which this book takes its title, the 1991 7-inch single by the aforementioned Sebadoh, provides a more economical telling of how this all went down in a sort of half-novelty, half-genuine, but one hundred percent rocking fashion. Reading about that 7-inch single prior to purchasing it marked my first real exposure to the term “indie rock,” and it was a godsend at the time, as I didn’t have a name for this music that had been blowing my mind and changing my life over the previous year or so. “What do you have that sounds like Dinosaur Jr?” was getting snickers during my twice-monthly, paycheck-eating forays to the only record store in town that had a clue at the time. Of course, this was the same year that Nirvana’s Nevermind struck chords at all points from the underground to the mainstream. At a distance of over two decades, that album is now appropriately regarded among the great lines of historical demarcation in music and culture. (Though it should be mentioned that, pre-Nevermind, a number of acts from the indie rock world had already made forays into the realm of major labels, including but not limited to, the Replacements, Hüsker Dü, Soul Asylum, Sonic Youth, Pixies, Dinosaur Jr, and Eleventh Dream Day.) Indie rock and some of its satellite subgenres (including, yes, indie rock) ascended—some voluntarily, others not so much—to greater levels of exposure, acceptance, and sales. Subsequently, a substantial number of the bands in this book, those that built grassroots DIY followings or maybe just had one or two albums on an independent label, entered into relationships with major labels and released at least one brilliant album through said channels. Underground rock’s written history as it stands today paints the major-label feeding frenzy of the early to mid-’90s as a black-and-white, good-versus-evil full-scale corruption and co-opting of the once-pure independent, DIY landscape (or an injurious attempt at doing so). While there is some validity in that line of thinking, the thorough and accurate narrative is much more complicated. And it is a narrative for

INTRODUCTION

5

another book. This one is concerned only with the strength of an album as a singular creative and cultural document, regardless of the label or imprint logo on its sleeve. Throughout this book, the reader will be beaten over the head with the term “indie rock,” but it’s impractical and impossible to use it to mean “underground rock that is exclusively the domain of independent labels.” While writing this book, I had very little contact with other humans aside from my fiancée. But of the few people to whom I did mention the project, some had an immediate head-scratching reaction to the years that frame it. Though 1979 and 1980 did see the releases of some rather seminal albums that influenced what was to become indie rock, it wasn’t until 1981 that the gates opened. Albums by Agent Orange, the Replacements, X, Black Flag, Gun Club, Wipers, the dB’s, Big Boys, Glenn Branca, Flesh Eaters, Mission of Burma, Half Japanese, Adolescents, TSOL, Sleepers, and the Minutemen, among others, just helped to make 1981 a more sensible starting point (though it pained me to exclude the Feelies’ Crazy Rhythms). Capping everything off with 1996 was a more difficult call. That was a year of transformation in the underground, as indie rock was by then three or four years into a growing backlash. 1996 also marked the first full year of serious encroachment of underground hip-hop, electronica, post rock, widescreen avantpop, and other styles that would soon drive guitars deeper into the metal- and hardcorebased undergrounds. These changes and the previously mentioned backlash enjoyed a relationship of cultural reciprocity. By default, an alphabetized list of 500 albums spanning fifteen years comprises something of a historical outlay of what happened in the American underground during that period, though it is a limited view with inherent chronological challenges and limitations when it comes to addressing all of the characteristics that compose the accurate big-picture history, including ’zines, regional scenes, live shows, 7-inch releases, and label histories. It is with this in mind that I strongly suggest the books listed in the back of this one, namely Steven Blush’s American Hardcore: A Tribal History, Second Edition; Michael Azzerad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground 1981–1991; and especially Joe Carducci’s three music-related books to date: Rock and the Pop Narcotic, Enter Naomi, and Life against Dementia. The book you are holding is intended to complement those titles, not be a comprehensive history of the period and its music. (Oral histories of regional scenes are increasing in number and are also recommended.) Readers of a certain vintage remember when record guides were common in the music section of a bookstore. Today, underground heavy music/metal is the only subgenre that still seems to be serviced by books of a similar nature, a fact that can be attributed to that community’s stronger sense of fan loyalty. As for the music covered in this book, straightup record guides were made obsolete once the sounds of yesterday and today could be

6 GIMME INDIE ROCK

readily sampled on the Internet. This transition made perfect sense for at least a decade, until myriad variables caused a saturation of information and made separating the signal from the noise more challenging than it was even in the pre-Internet days. Unlike some of my similarly aged colleagues in music writing, I find no reason to romanticize a time when one had to scribble lists based on reviews read in ’zines and magazines, videos seen on MTV’s 120 Minutes, overheard comments (if you were lucky enough to have friends who were into this stuff), and flimsy clues like album covers, label reputation, and band member crossover. Dropping $50 on seven to ten albums (new vinyl cost an average of $6 to $9 in the late ’80s and for much of the ’90s) and getting one or two sterling keepers out of the stack was considered a successful venture. However, I’d be a liar if I said I don’t have a tinge of nostalgia for the record guides that were so crucial to the development of my personal frame of reference and tastes as a lifer, namely Robert Christgau’s Record Guides for the ’80s and ’90s and Ira Robbins’ Trouser Press Record Guides (all editions). So, with all of this in mind, the 500 profiles that follow are meant to assist in online and brick-and-mortar explorations and hopefully be of some value as a historical survey of the period. Please note that the subtitle reads “500 Essential. . .” rather than “The 500 Essential. . .” This book in no way claims to be the definitive canon of the movement and period covered within. However, I do feel it is a pretty solid indoctrination, and it’s my hope that it can be of use to readers of all ages, from novices to grizzled and cantankerous know-it-alls. The use of “Essential” rather than “Influential” or “Important” is of even greater, uh, importance. Not all of these albums are “influential”; in fact, many remain buried in an abyss of obscurity. But the least-heard albums are just as “essential” as the general-consensus classics. As for the latter, naturally their status played into their inclusion. At the end of the day, though, the reader should just think of each as a great album within its respective style. First and foremost, these titles were chosen based on their individual strength, which took priority over criteria like band legacy or band discography. For instance, there are bands here of which I am not a fan (to say the least), yet I recognize their significance. As of this writing, some of these albums have been reissued several times and are easy to find. Many have never gone out of print. Others are simply amazing records that were released to a deafening silence. Then there are the albums that are out of print, highly sought-after, and generally exalted, thus commanding anywhere from $50 to the price of a decent used car for an original vinyl copy. And although stating the current status of each album’s availability would threaten to date the profiles, one admittedly idealistic hope for this book is that it will remove some of the above-mentioned titles from the margins of historical neglect or dismissal, and put them in the crosshairs of those with reissue powers. If this book somehow directly or indirectly leads to the reissue of more than one out-of-print title, it will be a personal triumph. —Andrew Earles, June 2014

INTRODUCTION

7

100 FLOWERS — AUTOCLAVE

100 FLOWERS S/T (1983, Happy Squid) The Urinals were a late-’70s/early-’80s trio of wiseasses who could play their instruments just fine but performed as ineptly as possible to aggravate audiences and offer a satirical (decidedly art-school) statement regarding the band’s feelings about punk rock. The Urinals never released a full-length LP. (Some demo material and two 7-inches made it onto the Amphetamine Reptile–released retrospective collection Negative Capability . . . Check It Out! in 1997.) When the band morphed into a more serious venture, the name changed to 100 Flowers and the trio released this first-rate Americanization of U.K. pop-oriented post punk. The sound was similar to the shambling Wire heard on the transitional 154 album, early Mekons, Alternative TV, and any number of the rocking but more approachable Rough Trade bands. This album, along with the EP that followed it and other tracks, was reissued in 1990 by Rhino as 100 Years of Pulchritude. A MINOR FOREST Flemish Altruism (Constituent Parts 1993–1996) (1996, Thrill Jockey) Active from 1992 until 1998, this enigmatic trio released two full-lengths: Flemish Altruism and a follow-up, Inindependence (also on Thrill Jockey, in 1998, and highly recommended), and enough material on 7-inches and compilations to justify the excellent two-CD odds-and-such So, Were They in Some Sort of Fight? (My Pal God Records, 1999). Flemish Altruism worked the margins of noise-rock, math-rock, and ’90s heavier post-hardcore subgenres—exactly the categories A Minor Forest was lumped into (when noticed at all)—by employing smarts, authentic heartfelt hooks, and a serious jones for complicated prog-rock time signatures, stretched-out quietness, and city-leveling noise. Fans of Slint and Co. take note.

10 GIMME INDIE ROCK

ADICKDID S/T (1993, Imp/1994, G Records) This all-female punk/noise-rock/heavy-indie trio was founded by Kaia Wilson, who went on to co-found the better-known Team Dresch and the Butchies. As of this writing, the amazing Adickdid remains barely a footnote in the history of the Pacific Northwest all-girl/riot grrrl/queercore movements (Kaia was active in the latter). Within the bigger picture of early ’90s underground indie/ punk/post hardcore, the band is totally unknown. Adickdid released one full-length and a 7-inch during its existence, plus it appeared on the second Kill Rock Stars compilation, Stars Kill Rock. Wilson has a true gift for marrying the pretty (her singing and vocal hooks) with the heavy and noisy, and it’s clear by listening to this record that she was an integral part of what made Team Dresch the baddest and best in the land (regardless of gender). Adickdid is much different, however, going into and out of sludgy, slower Melvins-ish territory throughout this album, but Wilson’s songwriting gift is on full display from front to back. It’s a lost gem. ADOLESCENTS S/T (1981, Frontier) The first incarnation of this band—they have regrouped many times over the years—was a sort of early-’80s L.A. hardcore/punk super group with Rikk and Frank Agnew (late of Social Distortion, but soon to be in countless bands) on guitars, drummer Casey Royer (who was also in Social Distortion), and former Agent Orange bassist Steve Soto. Singer Tony Cadena was only sixteen when Adolescents formed in 1979; he would go on to be in White Flag and other bands. Like Agent Orange’s Living in Darkness, Bad Religion’s How Could Hell Be Any Worse?, and Descendents’ Milo Goes to College (all released in ’81–’82 by these other L.A.-area bands), the Adolescents’ self-titled debut presents a type of melodic first-wave hardcore that puts the hooks up front and is more or less the blueprint for what would become the SoCal poppunk sound as the years went on. Adolescents is also one of the first hardcore albums to feature two guitarists, and both traded off on leads. When it came to their musicianship, the

A

11

Adolescents did not subscribe to the learn-in-public approach that was not uncommon within that scene. The Agnew brothers were accomplished and could whip out continuous leads that were almost song-length. And when it comes to these thirteen songs, there isn’t a dud in the bunch, Behind the Dead Kennedys’ Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, this is the best-selling California first-wave hardcore album.

AFGHAN WHIGS Congregation (1992, Sub Pop) The Afghan Whigs’ first two albums, 1989’s Big Top Halloween and 1990’s Up in It, delivered competent indie-grunge of the somewhat aggressive nature, while the latter even dabbled in what was to come (some emphasis must be placed on the D-word here). Released the same year that began with Nirvana escorting Michael Jackson to the exit door, Congregation was one of the special antidotes to the already-in-progress multilevel homogenization of the indie/alt-rock landscape. All of the revisionist talk of an R&B/soul-plus-indie rock hybrid when it comes to the Afghan Whigs’ post–Up in It material is a bit misleading, especially when it comes to this album. Not to say that Congregation wasn’t a severe left turn into new territory, but it was more of a maturation and naked, metaphor-free response to the buried vocals and ironic posturing that marked much of the indie rock landscape in 1992. Nowhere was this more evident than in the clear and intense lyrics and vocals for major-chord rockers “I’m Her Slave” and “Turn on the Water” (both of which received decent rotation on MTV’s 120 Minutes), not to mention the duo of disturbingly honest “ballads” toward the end of the album, “Let Me Lie to You” and “Tonight.” Congregation was a different and refreshing take on the alt/indie influx of the early ’90s—albeit a decidedly anti-grunge communication of real relationship/romantic sentiment and conflict in a manner that was an adult alternative to the coming flurry of ’90s emo. It was also the warning shot for the band’s attempted world takeover that would be the 1993 major-label debut, Gentlemen.

12 GIMME INDIE ROCK

AFGHAN WHIGS Gentlemen (1993, Sub Pop/Elektra) As the Afghan Whigs toured to support the critically acclaimed Congregation, the band grew a nice following and found itself at the center of a notoriously excessive major-label bidding war. Dulli’s personality as a conflicted, uncomfortably honest alpha-male antihero with an insatiable appetite for romantic misunderstandings came to the forefront on the band’s majorlabel debut, Gentlemen. The album brings to fruition what Congregation hinted at: fusing R&B and soul with thinking man’s guitar rock (in an indie/alternative context) and setting the band apart from the grunge-saturated pack. Gentlemen was recorded in Memphis at Ardent Studios, which spun off from Stax Records decades earlier. Stylish, fist-in-the-air modern rockers like the title track and “Debonair” got some MTV 120 Minutes rotation, and the album did go on to move more than 160,000 units. AGENT ORANGE Living in Darkness (1981, Posh Boy) The conservative suburban nightmare just south of urban L.A. known the world over as Orange County is widely considered the birthplace of American hardcore, thanks to the short-lived outfit Middle Class, who released a four-song 7-inch EP titled Out of Vogue in 1978. The O.C. would export its first wave of hardcore bands a couple of years later, starting with the Adolescents, Social Distortion, D.I. (Drug Ideology), and TSOL, along with Agent Orange, the band behind this charming and peerless little LP. On Living in Darkness, guitarist, vocalist, and founder Mike Palm realized a vision that, on paper, comes off as a recipe for failure. It shouldn’t have worked when Palm pushed surf-rock guitar, melodically moody punk rock, condensed pre-thrash metal riffs, and arena rock hooks through the filter of contemporary hardcore, but what came out was a disarmingly catchy, mature, approachable, and charming document. Living in Darkness mostly avoids the shortcomings associated with the first full-lengths by most hardcore bands of the day. Highlights are certainly “No Such Thing,” “Everything Turns Grey,” and the iconic “Bloodstains” (an earlier recording of which served as the A-side to the band’s debut three-song 7-inch in 1980 and as the opening track on the Rodney on the ROQ compilation LP).

A

13

Though the albums and their makers have little in common musically and thematically, Living in Darkness and Descendents’ Milo Goes to College (New Alliance, 1981) just might share the historically significant distinction of being the first two albums to deliver nearly flawless melodic hardcore. ALICE DONUT Revenge Fantasies of the Impotent (1991, Alternative Tentacles) After half a decade and three albums, this depraved combo of New York City weirdoes added a third guitarist and left behind some of their smirking Zappa-meets-Butthole Surfers irreverence for this release—the first of two Alice Donut albums (the other being 1992’s The Untidy Suicides of Your Degenerate Children) that reached heavier, abstract-metal heights, overshadowing the band’s former reliance on bad acid-trip nonsense and themes akin to a PG-13 version of iconic punkrock transgressor G. G. Allin. The intelligent, abstract metal thrust and downplaying of vocalist Tomas Antona’s polarizing screech makes tracks like “My Best Friend’s Wife,” “What,” and “Telebloodprintmeadiadeathwhore” stand above anything the band previously accomplished. An instrumental version of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs” (with the vocal line provided by a trombone) actually rocks while wearing a smirk. Critics tended to despise Alice Donut, even as the “alternative nation” blew up and became a household cultural happening in the wake of Nirvana’s success. Alice Donut broke up in 1996 but regrouped in 2001 and has been sporadically active since. AMERICAN MUSIC CLUB Everclear (1991, Alias) San Francisco’s American Music Club’s third album was good. (California, from 1988, was the band’s first step on the ladder to a cult following.) The next one was better. (United Kingdom in 1990 was only available in its namesake.) But the band’s fifth release, Everclear, made founder/leader/vocalist/multiinstrumentalist Mark Eitzel a songwriter for the ages. Often incorrectly called “slowcore” due to down-tempo material and a loose association with fellow Bay Area band Red House Painters, American Music Club’s arrangements are much more varied, and the nakedly catastrophic lyrical themes commonly benefit 14 GIMME INDIE ROCK

from an impassioned, two-minutes-this-side-of-a-breakdown vocal style that is unbelievably strong stuff—and perhaps best reserved for a good day if the listener is susceptible to fragility. The album features the two best examples of the band’s many heart-shattering songs about AIDS: “Sick of Food” and “Rise,” with the latter gaining some attention on MTV’s 120 Minutes. Everclear was ranked the year’s No. 5 album by Rolling Stone, and the same issue named Eitzel “1991’s Songwriter of the Year.” But the accolades reportedly left the AMC leader more freaked out than appreciative. AMERICAN MUSIC CLUB Mercury (1993, Reprise) If Everclear perfected AMC’s brand of cathartic release, then Mercury took it up a notch. Critical speculation abounded as to why the band would, for its major-label debut, release such a dark, starkly honest, and potentially alienating album. To many, it seemed like a reaction to the placement of AMC and Mark Eitzel on a pedestal after Everclear. But while this indeed may have been the most depressing album released by a major label since the big boys first steered any attention toward the American underground in the mid-’80s, Mercury is also the band’s best and most varied work. It covers a full spectrum, from minimal arrangements all the way to bone-rattling noise, all in support of Eitzel’s tales of human desperation. ANASTASIA SCREAMED Laughing Down the Limehouse (1990, Roughneck/Fire) With a band name like Anastasia Screamed, a tendency to turn up in dollar bins, and cover art suggesting an allergy to guitars (of the goth alternative variety favored by mid-to-late-’80s clove cigarette enthusiasts), this album makes it easy for potential buyers to write it off. The minimal buzz this band generated during its brief (1987–92) existence has been all but erased by history, rather than flowering into a posthumous legacy of respect and influence, like those bestowed upon fellow Bostonites Pixies and Mission of Burma. Anastasia Screamed had moved from Beantown to Nashville by 1990, signing to the Rough Trade– distributed and funded Fire Records subsidiary Roughneck. But Rough Trade’s cataclysmic 1991 bankruptcy landed an untold

A

15

number of albums by unknown-to-legendary bands in cutout bins. This album was one of the many casualties. Among the contemporaneous influences that work their way into this amazing collection are Squirrel Bait (especially in the rural-feeling, multifaceted style of vocalist Chick Graning), Dinosaur Jr, Volcano Suns, Thin White Rope, Big Dipper, Giant Sand, and Uncle Tupelo. (No Depression was released the same year as Laughing Down the Limehouse.) But this stuff doesn’t have a ruling reliance on any other band’s sound; the LP pulls off being wildly varied in a natural manner. Graning’s singing can reach a reedy high register, a sound that would emerge as rule-of-thumb about five years later with a great many bands in the decade’s emo movement. More explosive tracks like “Lime” and “The Skinner” are where the band really pulls out the goods. Each pulls off a weird trick: the song shifts into a fake collapse of structure that follows a dramatic and beautiful vocal hook down the hole to freeform noise or silence; then everything stops and the band locks back into the previous tempo. It’s quite effective. Curious readers are truly encouraged to put aside a buck or two for this one—and listen immediately. You’ll get your investment back in spades. ARCHERS OF LOAF Icky Mettle (1993, Alias) Archers of Loaf emerged from the same Raleigh-DurhamChapel Hill scene as Superchunk and Polvo, and like the former, became one of many bands that the music press, covering both the aesthetic and sonic aspects of the band, made sure was immediately synonymous with the term “indie rock.” Archers’ stunning debut, Icky Mettle, embraces a hint of melodic hardcore (or the post hardcore of the era) and has one of the best uses of quiet-to-loud dynamics up to that time. Sincerely impassioned vocals occasionally give way to screamed discontent, yet the album never strays from some application of warm melody. Another secret weapon used throughout the album (and unleashed in a brilliant fashion live) was the band’s fully formed dual-guitar interplay, alternately recalling or updating the approaches of bands like Television, Dream Syndicate, Fugazi, and Sonic Youth. The album’s final five songs (or most of the vinyl’s second side), beginning with “Learo, You’re a Hole” and concluding with the beautiful “Slow 16 GIMME INDIE ROCK

Worm,” cannot be topped as an amalgam of the components that could elevate good indie rock into the realm of great indie rock. Response to Icky Mettle was quite positive. The album spent twenty-two weeks on the CMJ charts, was voted Best Indie Rock Album of the Year by Interview magazine, and was given an “A” in Robert Christgau’s “Consumer Guide” column. As the decade closed, Pitchfork’s original “Top 100 Albums of the 1990s” ranked the Archers’ debut at No. 32. ARCHERS OF LOAF Vee Vee (1995, Alias) The band hailed from North Carolina’s “triangle”—Chapel Hill, Raleigh, and Durham—one of the country’s healthiest and least corruptible regional scenes (home to Polvo, Superchunk, Small (23), Pipe, Flat Duo Jets, and the area’s indie rock stamp of quality, Merge Records). But Archers of Loaf showed a strong and confident identity all its own on the band’s excellent first album, Icky Mettle. Though things don’t always work out this way for similarly talented and inspired bands, Archers’ debut netted the returns a great entrance should bring its makers: positive accolades and new fans across the country. It didn’t hurt that anyone unfamiliar with the band’s recorded output could catch the band passing through town during the intense touring schedule that followed Icky Mettle. An adventurous or curious concert attendee was bound to come away from these incendiary, passionate performances a dedicated convert. What all this means is that Vee Vee’s release in March 1995 was preceded by high anticipation. And while unrealistic expectations directly impacted the album-to-album sound and creative flow of their contemporaries in various ways (Pavement is a perfect example), Archers of Loaf channeled their early reception like pros and used night after night of gigging in front of tiny-tomoderate crowds as a tool of refinement. Vee Vee is an album of greater strengths and maturation (but rest assured, the M-word here is not a kind way of saying the band unwisely watered down its sound).

A

17

ARCHERS OF LOAF All the Nations Airports (1996, Alias/Elektra) Archers of Loaf remained on Alias while a distribution deal was struck with Elektra specifically for their third full-length, All the Nations Airports. The album is essentially an extension of Vee Vee—and more of what made that album so great is a good thing. Of note are the instrumental songs and the long instrumental sections of other songs, which together occupy a conspicuous amount of sonic real estate on the album, wielding the power to earworm into one’s head for days. Elsewhere, the title track, “Bones of Her Hands,” and the swelling intensity of “Distance Comes In Droves” would sound at home on Icky Mettle. The piano ballad “Chumming the Ocean” is melancholy gold, and the similarly played instrumental “Bombs Away” closes the album in fine form. ARCWELDER Pull (1993, Tough and Go) This Minneapolis trio was originally known as Tilt-A-Whirl until the manufacturer of the same-named carnival ride sued the band over copyright infringement. So, instead of undertaking a court battle that surely would not come out in the musicians’ favor, the band quietly changed its moniker to Arcwelder, after an instrumental that appeared on its 1989 debut full-length, This. Arcwelder straddled a fine line between finely crafted indie rock and its less-friendly cousin (and offshoot), noise rock. Pull was the band’s third full-length and the first to see the band packing an entire album with what it was good at. Comparisons to Hüsker Dü and Sugar were common due to drummer and vocalist Scott MacDonald’s dead-on Bob Mould–style singing, but Pull has enough aggro-rock Big Black/Naked Raygun-isms to distance it from the more accessible approaches used by what was nonetheless a very, very big influence (regionally and otherwise).

18 GIMME INDIE ROCK

ARCWELDER Entropy (1996, Touch and Go) Skipping over Arcwelder’s fine and endorsed fourth album, Xerxes (1994, Tough and Go), to land on the band’s next-to-last fulllength, Entropy, we see the Minneapolis workhorse offering up one of the mid-’90s best indie rock albums at a time when such a thing was promptly going out of favor in the underground. Side two’s opener, “I Promise Not To Be An Asshole,” is as great a song as any that Arcwelder’s better-known contemporaries would release in the 1990s, and it is the encouraged go-to for readers curious as to what exactly it is that makes this band a cut above the din of the day. AUTOCLAVE S/T (1991, Mira) One of many early-’90s surprises from a label that uninitiated listeners and critics often misunderstood as an incubator for Fugazi clones, Autoclave was an all-girl quartet with a prodigy-like knack for crafting catchy and complex post-hardcore material. The band’s output achieved extremely high quality during its mere eleven months of existence, and only consisted of this EP; a three-song, 7-inch EP; and a compilation track. Helium, Wild Flag, and Slant 6 fans take note: while it sounds nothing like any of those bands, this is the recorded debut of both Mary Timony (of the former two) and Christina Billote (of the latter). But don’t skip the record due to early-career misstep phobias. Rest assured; from the get-go, these ladies knew exactly what they were doing.

A

19

BABES IN TOYLAND — BITCH MAGNET

BABES IN TOYLAND Spanking Machine (1990, Twin/Tone) Singer/guitarist Kat Bjelland—formerly of San Francisco and once a roommate and bandmate of Courtney Love—formed Babes in Toyland in 1987 with Lori Barbero after the two met at a Minneapolis backyard barbeque. Originally, Love joined Barbero and Bjelland in Minneapolis to fill the new group’s open bass position, but the future Hole front woman was pinkslipped after just one practice. Michelle Leon then joined as bassist, and Barbero, who had never played drums, learned her instrument in public as the band honed its aggressive fusion of garage rock and noise rock, one often distinguished by Bjelland’s intimidating howl. Babes in Toyland debuted on vinyl in 1989 with the Sub Pop Singles Club 7-inch “Dust Cake Boy,” then released its first fulllength, Spanking Machine, the following year on hometown label Twin/Tone Records (with “Dust Cake Boy” as its next-to-last track). The album’s primal stomp was garage-rock-simple in nature but executed with such ferocity that any and all retro-leaning aspects of “garage” (i.e., any nods to Nuggets- or Pebbles-style ’60s garage or subsequent revivals thereof) were unapparent. Thus, Spanking Machine held up to the heaviest and most nihilistic of noise rock that was then coming out of another hometown outlet, Amphetamine Reptile Records. Sonic Youth’s members were such fans of the album that they invited Babes in Toyland to occupy opening slots of the European tour promoting the Goo album. This led to the Minneapolis trio being featured in the S.Y. Reading Festival concert movie 1991: The Year Punk Broke. Kat Bjelland’s tendency to wear white baby-doll dresses—in stark contrast to the vicious sound of the band—resulted in the press bestowing the unfortunate musical tag of “Kinderwhore” upon the band, which in turn prompted Courtney Love to make the (fraudulent) claim that the fashion was stolen from her.

22 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BABES IN TOYLAND Fontanelle (1992, Reprise) Touring behind its debut full-length (and a follow-up EP) tightened and crystallized Babes in Toyland’s femme-driven (but not actively feminist) blitzkrieg and built the band a following that unsurprisingly (in the days immediately following Nevermind’s success) attracted major-label suitors. The band went with the mostly artist-friendly Reprise imprint of Warner Bros. for its 1992 major label debut, Fontanelle. Expertly produced by Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo, the record not only marks Babes in Toyland’s career peak, but also easily stands as one of the more potent, accomplished (relative to its subgenre’s purposes), plus all-around sonically intense and challenging releases to not only appear on a major label (even then), but to result from the era’s notable increase in all-girl bands that was the source of media-generated blanket categorizing (riot grrrl, foxcore, etc.) Today, despite Babes In Toyland’s brief time as one of the better-known bands to emerge from the noisier corners of the underground, and the fact that Fontanelle sold over 250,000 copies, the album remains an overlooked gem. BAD BRAINS Rock for Light (1983, PVC) Brothers Earl and Paul “H. R.” Hudson, Gary “Dr. Know” Miller, and Darryl Jenifer are four African American musicians who grew up together in the Capitol Heights neighborhood of Washington, D.C., and formed a jazz-fusion band while still in high school. When punk rock blew their minds in 1977, the bandmates cribbed a new moniker from the Ramones song “Bad Brain” and parlayed their instrumental virtuosity into something so tight and fast that Bad Brains’ 1979 vinyl debut on the 30 Seconds Over D.C. compilation and the band’s first 7-inch, 1980’s “Pay to Cum,” are together widely considered the birth of East Coast hardcore. The quartet’s early live shows were frenetic, explosive, and life-changing for many crucial movers in the D.C. scene, including Minor Threat/Fugazi/Discord Records founder Ian MacKaye. Already into the reggae-leaning Clash records of the era, the members of Bad Brains became practicing Rastafarians after viewing the film Rockers and attending a 1980 concert by Bob Marley.

B

23

Relocating to New York City in 1981, Bad Brains released a self-titled debut on the cassette-only ROIR label that resonated throughout the hardcore community. A few professionally played reggae songs made the album—a precursor to the reggae-rock movement of the late ’80s—but the recordings suffered greatly from a brittle lack of dynamics resulting from a restrictive budget. Those problems were remedied on 1983’s Rock for Light, Bad Brains’ first true full-length, which was recorded by the Cars’ Ric Ocasek. More than half the cassette’s tracks reappear here as newly recorded versions with a big, brutal clarity afforded to few hardcore albums of the day. Reggae numbers professionally knocked out with effortless authenticity are interspersed with new thrash-core gems that retain the band’s note-perfect lightspeed treatment. Rock for Light is a record of transcendent power and easily one of the ten most important full-length albums released during the 1980–1983 coalescing of first-wave American hardcore. BAD BRAINS I Against I (1986, SST) I Against I is exalted as immensely influential, yet it’s nearly impossible to cite another album that sounds anything like it in the almost three decades since its release. Bad Brains’ third studio album took the idea of hardcore’s mid-decade crossover movement way beyond the mere incorporation of metal or melody (when most crossover hardcore bands could only handle one of those two stylistic shifts), and exhibited the band’s weird idea of pop, several strains of reggae, soul, funk, and metal. It should mean something that this is the only entry in these pages where the words “funk” and “metal” exist in harmony. Black Flag’s Henry Rollins brokered a deal between SST and Bad Brains in 1985, and the three years that had passed since Rock for Light saw the band dealing with, and causing, a mindblowing array of problems. The band spent all of 1985 rehearsing with a new drummer and one of many vocalists who tried to fill the shoes of the departed H.R., but once the studio sessions were on the horizon, H.R. and the band reconciled and managed to get Diana Ross producer Ron St. Germain to helm the board (and lend them money for the very expensive studio). To quote Steven Blush in his book American Hardcore, “I Against I rates as one of the 24 GIMME INDIE ROCK

greatest albums in Rock history.” The album made the original printing of the famous book, 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and has appeared on many historical “best of” lists over the years. It’s one of the best-selling albums in SST’s history. BAD RELIGION How Could Hell Be Any Worse? (1982, Epitaph) Like the Replacements’ Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash, this is punk rock abandon speckled with rock-and-roll flourishes (like split-second guitar leads), but revved up way beyond standard punk energy by the timeless engine of fist-in-the-air songwriting. Also like the Mats’ Trash, this work is one of America’s best lightning-in-a-bottle hardcore albums. While not quite as fast as Bad Religion would get in the late ’80s and early ’90s (after recovering from its mid-decade identity crisis), How Could Hell Be Any Worse?, gets the listener’s blood pumping as well as—or better than—many albums released by the titans of the same era. BAD RELIGION Suffer (1988, Epitaph) After Bad Religion’s self-released-and-distributed debut album sold roughly 12,000 copies (an achievement, given the circumstances and era), the group returned in 1983 with the disastrous Into the Unknown, an album of keyboard-driven, mid-tempo drivel that owes more to AOR outfits like Asia than to anything resembling the hardcore environment that bred the band. The ambitious but fatally flawed sophomore effort was so reviled by fans and, soon enough, the band itself (guitarist Brett Gurewitz has, many times, called the album a “misstep”), that Bad Religion only released the return-to-form EP Back to the Known in 1984 before going quiet for a four-year hiatus. Bad Religion returned in 1988 with Suffer. The second-wave melodic hardcore classic (by first-wavers, it’s worth noting) set the pace and more or less provided the model the band would work from for the high-output legacy of anthemic albums and legendary status among fans that continues today. Stuffed with breakneck tempos, amazing harmonies, and smart, thesaurus-worthy lyrics from the first track to the last, Suffer is pop-core gold that obviously influenced a new generation of bands (many of which would be on Bad Religion’s own Epitaph label) over the next decade.

B

25

BAILTER SPACE Vortura (1994, Matador) Vortura was Bailter Space’s first album as an American band, having relocated to New York City from New Zealand during the recording process for their previous album, Robot World, the trio’s first for Matador Records (and third overall). Alister Parker, John Halvorsen, and Brent McLachian played together as New Zealand post-punk band the Gordons until 1987, when Parker formed Nelsh Bailter Space. Halvorson joined up by the time debut full-length Tanker was released in 1989 under the shortened moniker Bailter Space, and McLachian was back playing with his former bandmates for the next album, Thermos, released in 1990 (both albums were on New Zealand’s legendary Flying Nun label). During these early days of the band, the trio bounced around different home bases in Germany, New Zealand, and the United States, but settled in the latter in 1993. Bailter Space’s several-year stint on Matador would produce the band’s best work and signal a noticeable change in direction from the industrial and almost gothlike flirtations of the trio’s earlier output, with a much more dissonant, full, heavy, and melodic sound influenced by American acts like Dinosaur Jr and Sonic Youth, while putting a fresh, sometimes crushing spin on the then-diminishing shoe-gaze/noise-pop movement. And never was this phase of the Bailter Space sound more dissonant, fuller, and heavier than on Vortura. Songs like “X” and “Dark Blue” stand among the most massive noise-pop ever created. Bailter Space was known as one of the loudest live acts of the era in terms of sheer decibels, while Vortura combined the trio’s noise-sculpting, an obsession with harmonics, and the catchiest pop hooks they’d put on record to date. BAILTER SPACE Wammo (1995, Matador) As a lot of previously noisy American bands moved away from dissonance in a number of ways and the shoegaze old guard in the U.K. either disappeared (My Bloody Valentine) or underwent a Brit-pop makeover (Ride, Chapterhouse, Boo Radleys, etc.), Bailter Space’s final album for Matador (fifth overall) finds the band showing everyone how skilled it was at erasing any lines of demarcation separating wickedly catchy pop songs and washes 26 GIMME INDIE ROCK

of guitar noise and toothy dynamics. Singles “Splat” and “Retro,” along with “D Thing” and several other tracks on Wammo have Bailter Space hitting a home run with unprecedentedly clean and soaring vocal lines and infectious songwriting. BAKAMONO The Cry of the Turkish Fig Peddler (1994, Priority) Drawing inspiration from Boredoms, Sonic Youth, Slint, and the many weirdoes with which they shared a regional scene (Bay Area and Santa Cruz, home to Steel Pole Bathtub, A Minor Forest, the spazzcore scene, insanity-pop geniuses the Thinking Fellers Union Local 282, and so on), the spastic and surprising Bakamono occupied the opposite end of the noise-rock spectrum from bands such as Helmet or Tar when it came to songwriting. Each of the six extended songs on Bakamono’s debut long-player, The Cry of the Turkish Fig Peddler, is a miniature suite of multiple moods, tempos, dynamics, and general capacity for variety uncharacteristic of the noise-rock faction. Bakamono drew from early-’70s space-rock pioneers Hawkwind and harder prog-rock/ Krautrock bands of the same era just as much as it did from more contemporary racketmakers, adding a lot of personality and surprise passages of rhythmic interludes midsong. (Each track turned on a dime several times and explored many methods to the madness.) The vocals were another plus: distorted (as if sung through a two-way radio or megaphone several feet from a mic) and mixed lower than most bands. Japanese-American band leader Elso Kawamoto Jr.’s singing and screaming both were melodic and eschewed the alienating, up-in-the-mix testosteronebark favored by many of Bakamono’s contemporaries. BAND OF SUSANS The Word and the Flesh (1991, Restless) The original lineup of this band indeed featured three women named Susan. And never did it have fewer than the same number of guitarists, though Band of Susans is perhaps best known for one guitarist in particular—a former Glenn Branca pupil named Page Hamilton who was around long enough to be credited on 1989’s Love Agenda before leaving to form Helmet. Formed and maintained for a decade of activity by the core of Robert Poss (guitar/vocals and a former member of Rhys Chatham’s

B

27

ensembles), Susan Stenger (bass/vocals), and Ron Spitzer (drums), Band of Susans were part of New York’s post-no-wave scene that included Sonic Youth, Swans, Live Skull, and The Unsane, but one wouldn’t know it by their trademark sound of Anglophile shoegaze/drone-and-dream-rock meets the aforementioned gazillion-guitar composers. Guitarists Mark Lonegran and Anne Husick joined up for The Word and the Flesh, Band of Susans’ strongest rock-centric, song-concerned album, and their first with genuine hooks/catchiness rather than just melodies. BAND OF SUSANS Here Comes Success (1995, Restless) Band of Susans shifted to a slightly different sonic cause after the half-decade that coalesced with 1991’s The Word and the Flesh. While 1993’s Veil finds the quartet in too much of a reconnaissance mode, looking for what it would then perfect on its fifth and final record, the sarcastically titled Here Comes Success, whose nine songs average seven minutes in length and are often driven by the simple but mammoth bass lines of Susan Stenger (the album is her showpiece in the band’s discography). Ignored to this day, Here Comes Success deserves company with other seminal “guitar albums.” Some fascinating trivia: the band favored G&L guitars, along with Fender offsets (Jazzmasters, Jaguars, Mustangs, etc.), and let the world know by featuring or posing with these guitars on album covers. Leo Fender, the man responsible for bringing these brands and models into existence (G&L was his post-Fender venture), was a rabid Band of Susans fan and friend of Poss until his death in 1991 at age eighty-one. BARDO POND Bufo Alvarius, Amen 29:15 (1995, Drunken Fish) The “drone-rock,” “free-rock,” or “noise-drone” mini-genre offshoot of America’s indie underground really got its legs in the early ’90s, spearheaded by Kranky Records and this label, with some influence coming from outside the United States (mainly New Zealand’s Dead C and associated Xpressway label). Philadelphia’s Bardo Pond relied more on basic rock structure than many of its more freeform peers, and the band was clearly moved by the first-wave noisepop/shoegaze bands from the U.K. (Loop, Spacemen 3, My Bloody Valentine, and so on) as well as the heavier Krautrock notables like

28 GIMME INDIE ROCK

Guru Guru and Ash Ra Temple. With vocals by a statuesque blonde flutist with an angelic voice—and an instrumental onslaught of scuzzed-out, layered, minor-key guitar that threatened to willfully bury her role in the songs—Bardo Pond excelled when the band eschewed meandering jams for loose but exceptionally loud and heavy sludge-rock/pop. Bufo Alvarius, Amen 29:15 is that Bardo Pond, highlighted by the mournfully moving tracks “Adhesive” (the instrumental opener) and “Capillary River.” BARDO POND Amanita (1996, Matador) Longer than its predecessor, better recorded, and with superior song craft that justifies Bardo Pond’s fondness for extended jams, Amanita, along with the band’s next album, Lapsed (Matador, 1997) remains one of the highest quality works in a prolific discography that grows to this day. The album had a wide-ranging influence, blowing minds within the more experimental and adventurous indie rock–based realms (which the band called home), reaching into the then-blooming stoner-metal (or stonerrock) scene, and establishing a historical milestone for today’s right-headed bands that were too young the first time around. BASTRO Diablo Guapo (1989, Homestead) After the band Squirrel Bait broke up, founder and guitarist David Grubbs moved to D.C. to attend Georgetown. (He was in high school during Bait’s period of activity.) Soon, Grubbs started making a more aggressive type of post hardcore/noise rock under the moniker Bastro. Ex-Squirrel Bait bassist Clarke Johnson joined up, and the two made the Rode Hard and Put Up Wet EP with a drum machine and Steve Albini in the engineering role. The record was released by Homestead Records in 1988. After drummer John McEntire (formerly of My Dad Is Dead, and later with Tortoise) joined Bastro to add a human hand to the kit, the band scrapped original versions of ten of the twelve songs destined for Diablo Guapo and recorded much faster takes with engineer Brian Paulson. The result? A twenty-eight-minute gem. Its weird time signatures and abstract flourishes do not derail the intense velocity and prescient heart of this awesome noise-rock power trio.

B

29

BASTRO Sing the Troubled Beast (1991, Homestead) David Grubbs spent some time in Bitch Magnet during the two years between Diablo Guapo and this, Bastro’s final album. The trio gained another future Tortoise member when Johnson’s departure brought in bassist Bundy K. Brown. A wider variety of instruments and weirdness (especially the growing obtuseness and distinct cadence of Grubbs’ vocal style, which will not sound unfamiliar to fans of his next project), do make for a somewhat different album, but Sing the Troubled Beast is still one of the early-’90s’ best examples of thinking man’s noise rock. The band toured with Codeine and then relocated to Chicago, where Grubbs attended graduate school at the University of Chicago and morphed Bastro into Gastr del Sol. Brown and McEntire contributed to the Chicago scene of experimentally minded (or “better than average”) indie rock and such, most notably as founding members of aforementioned post-rock poster band Tortoise. BEAT HAPPENING Jamboree (1988, K Records) Jamboree marked a big step forward from the naval-gazing pajama party that was this trio’s self-titled debut. Beat Happening is the Beat Happening of legend on this album—and the two that followed. The band’s signature sound also progressed over these three albums, with 1991’s Dreamy and 1993’s You Turn Me On (see entry) rounding out the trio of titles. The combination of founder/ vocalist/songwriter Calvin Johnson’s baritone singing and lyrics of a schoolyard-crush mindset, Heather Lewis’ simple but effective stand-up drumming, and Bret Lunsford’s minimal strum/jab/ jangle guitar could have been one of the more difficultly acquired tastes in American underground rock. But it had a distinct power to endear, providing one of the era’s most pointed reactions to the boys’-club post hardcore, proto-grunge, noise rock, and other prevailing indie rock sounds, all of which were growing in popularity in 1988, the year this album was released. Jamboree features definitive Beat Happening moments “Bewitched” and “Indian Summer.”

30 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BEAT HAPPENING You Turn Me On (1992, K Records) As its final proper album, Beat Happening’s You Turn Me On places the trio in one of rock-and-roll history’s most exalted secret-handshake clubs: bands that reach their A-game, release an album representative of this, and then promptly called it a day. You Turn Me On features exceptional if not infectious songwriting, long and hypnotic tracks with multitracked layers, a mature sexuality that was missing from previous releases (and so much of indie rock in general), and an overruling of the innocence factor that was, quite frankly, beginning to get a little creepy as Beat Happening progressed from album to album. (Calvin Johnson was thirty when You Turn Me On was released.) Johnson subsequently formed the frequently fantastic Dub Narcotic Sound System (with various side players) and the Halo Benders with Built to Spill’s Doug Martsch. BECK One Foot in the Grave (1994, K Records) Recorded in a single take as a tossed-off goof, Beck’s “Loser” was released as a 12-inch single in March 1993, originally in a tiny edition of five hundred copies. Picked up by numerous California radio stations, the song became a surprise hit, unwittingly typecasting a generation and making Beck the subject of a heated bidding war. This was the backdrop when, in November 1993, Beck traveled to Olympia, Washington, to record One Foot in the Grave, though it wouldn’t be released until the summer after his DGC debut, Mellow Gold, hit in April 1994. (An additional independent-label album, Stereopathic Soulmanure, a twenty-fivetrack noise-joke endurance test, was also released in the months following Mellow Gold, another testament to the level of creative control Beck managed to retain through his major-label contract.) One Foot in the Grave made sterling his credibility in the world of folk music interpreters and was recorded with a Pacific Northwest dream team of indie players, including Built to Spill/Spinanes/ Team Dresch drummer Scott Plouf, 764-HERO’s James Bertram on bass, and guitarist Chris Fallow, who’d soon sell a million records of his own as founder of the Presidents of the United States of America. On top of that, the album was produced and released by K Records/Beat Happening/Halo Benders/Dub Narcotic Sound

B

31

System ringleader Calvin Johnson. The result of this highly credentialed collaboration is an impressive selection of folk and folk-blues originals (and one cover of the traditional “He’s a Mighty Good Leader”), all bearing an uncanny resemblance to material found on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. BECK Odelay (1996, DGC) Beck’s fourth full-length album was a fleshed-out, multilayered, multistyle mammoth accomplishment that actually did what his second and third independently released albums were supposed to do: silence any lingering chatter about Beck being an integrity-challenged, one-hit musical entity. As the first Dust Brothers production since the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique in 1989, Odelay shares that album’s sense of artistic wanderlust and spot-on execution. The stylistic buffet includes the expected altindie hip-hop and electronica, but also goes into indie-fuzz-pop, underground nudge-nudge samples (like the Frogs’ “That was a good drum break” from the duo’s 1989 album, It’s Only Right and Natural), old school hip-hop, exotica, and even some stuff that could be classified as noise rock. Odelay set Beck on the wildly diverse career path that continues today. BEDHEAD Bedheaded (1996, Trance Syndicate) This album, somewhat superior to the band’s debut, presented a logically subtle progression of Bedhead’s sound and vision. Bedheaded was the band’s second triple-guitar contribution to raising indie rock’s mid-’90s approval rating. The 1998 Steve Albini–engineered Transaction de Novo was the band’s magnum opus—and its finale. The years that have passed since the six-piece’s 1999 breakup have seen a slow but noticeable reexamination of the band’s body of work—and a growing base of new fans too young to have found Bedhead the first time around.

32 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BIG BLACK Atomizer (1986, Tough and Go) After several years and a handful of EPs that felt like albums, Big Black released Atomizer in 1986 as its first true full-length. Like the barely posthumous Songs about Fucking that followed the next year, Atomizer is Big Black at the height of its two-guitarsplus-bass-plus-drum-machine powers, forging a line-straddling, industrial-meets-nascent-noise-rock force to be reckoned with. The album features the band’s best song, “Passing Complexion”; its best known song, “Kerosene”; its most controversial work, “Jordan, Minnesota” (about a 1983 child pornography ring busted in said town); and generally the harshest lyrical subject matter Big Black had yet to offer (with handy liner notes explaining each song’s little fictional foray into the American underbelly). It inexplicably cracked the Billboard 200 at No. 197, and it belongs in the collection of anyone with more than a passing interest in this book. BIG BLACK Songs about Fucking (1987, Touch and Go) With guitarist Santiago Durango deciding to enroll in law school, Big Black (two guitarists, a bassist, and an increasingly well-programmed drum machine credited on record sleeves as “Roland,” after its manufacturer) determined that Songs about Fucking would be its final release. Following the combo’s strongest effort to date, Atomizer (1986), Big Black’s swan song was no tossoff. Rather, it would guarantee founder Steve Albini’s first musical project (of an eventual three) a dignified and powerful exit. Without belying Albini’s electronic influences (Roland is front and center, and the LP included a cover of Kraftwerk’s “The Model”), Songs about Fucking was the heaviest, most lyrically poignant, and hardest-rocking of all Big Black titles to date (an EP, a live album, and a compilation would follow) and a certifiably essential part of any record collection, especially those that trod indie rock’s heavier paths. In fact, Songs about Fucking would prove a big influence on the growing “aggro” and “post-hardcore” corner of indie rock that would soon be the focus of the Amphetamine Reptile and Touch and Go Records in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

B

33

BIG BLACK Pigpile (1992, Touch and Go) Like other inherently flawed formats (compilations of non-album material, remix albums, and so on), great live albums are hard to come by. But what about an incredible live record by a rock band with a lineup that includes . . . a drum machine? Big Black pulls off that rare feat with Pigpile, which documents one complete show at London’s Hammersmith Clarendon during the band’s final tour. Big Black’s breakup was actually announced before the release of 1987’s Songs about Fucking and the shows—including the one captured here—that followed. The band called it a day based on two factors: Guitarist Santiago Durango was to soon begin law school and the bandwide assessment that Big Black had reached the height of its powers. Therefore, on this album, the latter is just what the listener gets, from the first “One, Two, One, Two . . . fuck you!” count-off until Steve Albini and Santiago Durango stab through the last couple of scratchy riffs on “Jordan, Minnesota.” Many of these twelve live tracks are better than their studio counterparts, namely “Passing Complexion,” “Pavement Saw,” and pre-LP era (1986) material such as “Steelworker,” which suffered from a poor recording when originally released. BIG BOYS Where’s My Towel/Industry Standard (1981, Wasted Talent) Fronted by 250-pound Randy “Biscuit” Turner, a proud homosexual who would wear tattered dresses on stage (this took serious guts in early ’80s hardcore), with guitarist Tim Kerr and bassist Chris Gates behind him, the Big Boys were the first and perhaps only creatively successful punk-funk band to come out of the early hardcore scene. Released before 1982’s Fun, Fun, Fun 12-inch EP, this album (known as either Where’s My Towel? or Industry Standard, depending on the pressing or who you ask) is the band’s only full-length recording made at the height of its artistic powers. Two full-lengths came later on the Enigma label, but the fire had been snuffed by that point. Along with the Dicks, the Big Boys were kings of Texas hardcore, and they offered something different and of lasting influence to later generations of underground bands. Tim Kerr went on form and play in countless bands, including Poison 13 and Monkeywrench. Turner passed away in 2005. 34 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BIKINI KILL Pussy Whipped (1993, Kill Rock Stars) Perhaps one of the most misrepresented entities when it comes to the music press of the early ’90s, Bikini Kill wasn’t really the proprietary band of riot grrrl’s original early- to mid-’90s run, but it was the act most often associated with the movement. Based on artistic/musical merit alone, Bikini Kill released two killer albums of female punk rock for the ’90s (and beyond). This was the band’s proper debut, a raging, screeching beast with an engine built from equal parts X-Ray Spex, Slits, Adverts, and Avengers, but with none of the fat evident in the ill-coined “foxcore” sounds of the day (L7, 7 Year Bitch, Hole, etc.). Pussy Whipped showed that the basic traditions of punk rock could be brought into the ’90s with conviction, excitement, and quality. BIKINI KILL Reject All American (1996, Kill Rock Stars) When the riot grrrl movement suffered widespread media distortion, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna called for its principals to participate in a “media blackout” during the couple of years leading up to her band’s final album. Cultural adversity has helped or wholly created some of the great albums in this book, and perhaps that’s part of the reason Reject All American eats the earlier Pussy Whipped for lunch in regard to production qualities, real anger, songwriting, and dynamics (or maybe it’s just creative progression on the part of the minds at work). Either way, Reject All American belongs in the femme-led mid-decade canon of greats alongside the first two Sleater-Kinney albums and the two Team Dresch titles. BITCH MAGNET Umber (1989, Glitterhouse/Communion) Bitch Magnet remains one of the more confusingly named bands in underground rock history (it was active during the pre-ironic era). Formed in 1986 amid the same social circle at Ohio’s Oberlin College that would spawn the like-minded Codeine, Bitch Magnet released the debut 12-inch EP Star Booty in 1988, followed by this full-length debut the next year. Umber showed that this trio favored an aggressive and heavy approach to post hardcore/indie rock that had a lot in common with the aggro noise rock that

B

35

dominated the Amphetamine Reptile and late-’80s Touch and Go rosters. But Umber lacked the unwieldy, testosterone-fueled depravity and nihilism that painted some of noise rock’s more homogenous participants into a self-defeating corner, relying instead on the hazy, often buried but melodic vocals of guitarist/ founder Soo Young Park (later of Seam) and a more tuneful wall of guitar riffs and distortion that actually compared favorably to early shoegaze techniques as much as it did the six-string onslaughts of stateside contemporaries.

36 GIMME INDIE ROCK

B

BLACK FLAG — BUTTHOLE SURFERS

BLACK FLAG Damaged (1981, SST) If this book’s 500 albums were to be arranged in exact chronological order by date of release, the opening statement of the resulting cultural and musical narrative would be this album. Black Flag’s Damaged is “overrating-proof,” if such a thing exists. The indelible mark it left upon its release—and the gradually growing influence it continues to exert upon underground rock— cannot be overstated. This was the first Black Flag album to feature Henry Rollins on vocals and the only full-length studio recording officially released by the band to feature its legendary two-guitar lineup. While earlier Black Flag material, spanning four years and employing as many vocalists, show the band excel at the really, really fast punk rock that was soon to be known as “hardcore,” Damaged is an altogether new development. The attack is not only incrementally more ferocious, direct, and lyrically introverted (or insane), but Greg Ginn’s songwriting and guitar work reaches its first adventurous peak with miniature atonal explosions of lead work flying from the the down-stroked fury of his riffs. Bracelets on drummer Robo’s left wrist can be heard rattling whenever he slams his snare—namely, during downbeats—and this became yet another audible quality mimicked over years to come. Henry Rollins’ vocals were recorded later than the backing tracks, and the closing dirge “Damaged I” is his first writing credit with the band. (He made up lyrics each night the song was performed.) Damaged was originally released through a distribution deal with MCA Records’ Unicorn imprint that quickly went south in a bad way. The complicated debacle cost the hardcore warhorses two years of productivity during which the band was legally disallowed any further releases under the Black Flag name. Though a valiant effort has been made within this book to keep to a minimum any attempts at ranking the works included herein, Damaged might come the closest to making that shortest of shortlists, the one inspired by the hypothetical scenario, “If your house was burning down and you could only save one album . . . ”

40 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BLACK FLAG My War (1984, SST) Due to the protracted, multilayered legal catastrophe that followed Damaged, My War arrived almost two and a half years later. The band’s second proper studio album is split in two stylistically disparate halves (that is, side one and side two). Five of the six songs on the first half are more or less an extension or expansion of the style originated and realized on Damaged. Side A closes with the completely unhinged “The Swinging Man,” a freakout of unbelievable proportions with Rollins convincingly losing his shit atop a performance by Greg Ginn that provides evidence the man never really got due credit as a phenomenal free-jazz/ improv/noise guitarist. Playing this one is an efficient way to clear out any party at four in the morning. Side B is just three tracks, each over six minutes long, played at a menacing crawl. It’s post-Sabbath sludge-metal or proto–noise rock, depending on how you wish to retroactively consider this stuff against the underground rock history that came before and has transpired since. What’s clear is that Greg Ginn and his close confidants were paying attention to the tiny but autonomous doom-metal scene that was fracturing away from the power- and thrash-metal movements (not such a reach considering that the new movement’s progenitor, Saint Vitus, had just released its debut full-length on SST a month before My War came out). Black Flag wanted to raise the bar set by fellow exploring hardcore colleagues Flipper, Void, and Fang. And, as with Flipper, part of the motive for such a drastic shift was the desire to aggravate narrower minded hardcore patrons who showed up to see Black Flag rip through a bunch of twochord, minute-and-half burners—a faction of fans and bands that had, unfortunately, grown into a nationwide movement majority by 1984. My War polarizes Flag fans to this day, but there’s no debating the mark it left on later trailblazers like the Melvins, Drive Like Jehu, Unsane, Mudhoney, and Nirvana—not to mention the influence it had on the seriously heavy and slow metallic rumblings of Kyuss, Sleep, and Earth.

B

41

BLACK FLAG Slip It In (1984, SST) This occasionally misunderstood album (the title track is deeper than many thought upon its release) is actually Black Flag’s strongest studio full-length after Damaged, but rating this band’s albums against one another distracts from the big-picture truth that each is more or less its own creation. That said, Slip It In is the only Flag album to deliver the band’s entire past-to-future stylistic gamut, and it rocks more thickly and fiery than any of the other four studio full-lengths that followed the band’s release moratorium, which ended in early 1984. Black Flag released three studio albums that year alone—My War in March; the half-spoken-word (by Rollins)/half-instrumental Family Man in September; and Slip It In, in December—as well as a live record. Landing before the band’s final album, In My Head, Slip It In is the preeminent (though a little inconsistent, fidelity-wise) release by the lineup of Henry Rollins, Greg Ginn, bassist Kira Roessler, and Descendents drummer Bill Stevenson. BLACK FLAG Live ’84 (1984, SST) This good recording of a show at San Francisco’s Stone nightclub (also filmed and available through SST on VHS for a short time) features the Rollins/Ginn/Roessler/Stevenson lineup in fine form. It starts with the eight-minute instrumental “Process of Weeding Out” that promptly reveals bassist Kira Roessler as an unsung secret weapon. (This version is preferable to the studio version on the 1985 EP of the same name.) There is heart to Roessler’s playing that counters Ginn’s atonal “anti-hook” freak-outs and riffs, which were really coming into play (more so live) in ’84. Everyone should hear this polarizing lineup when it was firing on all cylinders.

42 GIMME INDIE ROCK

BLACK FLAG In My Head (1985, SST) Black Flag entered a different phase for its final year-and-a-half (1985 to the summer of 1986). Flag of 1983–84 was contrary and visionary at same time: getting people’s attention, blowing away live audiences when not befuddling or infuriating the them, challenging the community’s thinking when it came to artistic limitations, re: hardcore, and helping (as much as any band in this book) to spawn what would become “indie rock.” But in later years, Greg Ginn’s artistic singularity and other issues began to alienate the band’s audience—particularly in a live setting. Flag’s final two studio records—the slightly weaker Loose Nut and the superior In My Head (both from 1985, SST)—are still sinking their influential claws into the rock and metal underground. Gone were the days of Damaged, which sold more than 60,000 copies within months of its release—in L.A. alone. But In My Head, which Greg Ginn had originally written as his first solo album, is the band’s most structurally tight studio document. It burns as wild and heavy as Slip It In but boasts clearer production and a faster drive. This is the exemplary studio capture of Black Flag/Greg Ginn’s late-days mixture of underground metal, twelve-tone experimental composition, and hardcore intensity plus density. BLAKE BABIES Sunburn (1990, Mammoth) Bassist/singer Juliana Hatfield, drummer Freda Boner, and guitarist/singer John Strohm began playing together at some point in 1986 and did so without a moniker until Allen Ginsberg gave them one—literally. After a reading at Harvard, the legendary Beat poet and writer entertained some attendee questions. Hatfield/Boner/Strohm asked for a band name; Ginsberg answered with an indirect reference to William Blake’s Songs of Innocence. From that origin anecdote (a damn good one) we advance to the band’s final album, Sunburn (1990), not to dismiss the Blake Babies’ releases leading up to it, but to spotlight the stylistic trophy piece released just a handful of months before the band’s 1991 demise. The Blake Babies hailed from the same underground Boston/Amherst collective of bands that included

B

43

the Lemonheads, Dinosaur Jr, and Buffalo Tom, yet the Blake Babies did not rely on piles of guitar distortion or an updating of regional forefathers Mission of Burma, and instead specialized in hook-savvy jangle-pop with an underground swagger, moody tension, and often-brisk delivery. However, most of the polite college rock coming out of the woodwork in the late-’80s and first year or two of the ’90s is put to shame by Sunburn. Shortly after its release and the band’s breakup, Hatfield went solo and, in 1992, released the album Hey Babe, one of the best-selling independent releases of the year. BLONDE REDHEAD La Mia Vita Violenta (1995, Smells Like Records) Named after a song by no-wave band DNA, Blonde Redhead was initially made up of Italian-born twin brothers Amedeo and Simone Pace and two Japanese-American women, Kazu Makino and Maki Takahashi. The band’s first two albums are unfairly dismissed as noise rock but are in fact a mix of Sonic Youth, Unwound, noisier shoegaze, and something that was all Blonde Redhead. The Smells Like Records label was run by Sonic Youth drummer Steve Shelley, and it’s not hard to imagine what he liked in the two records made by Blonde Redhead in 1995, though La Mia Vita Violenta, the band’s sophomore outing (the debut was self-titled), is the better of the two. Its instrumental and vocal bombast, inventive rhythms, and unique male/ female vocal interplay pushed right up front in the mix created a beauty-meets-chaos-in-the-future treatment of noise-pop that exemplified why Blonde Redhead was an invigorator for mid-decade indie rock. The album stands the test of time and is strongly recommended for fans of guitar-centric, aggressive, noise-embracing, and keenly melodic bands of today or since this band changed its sound mid-career. It’s worth noting that this incarnation of Blonde Redhead sounds very different from the one that has found a following in more recent years.

44 GIMME INDIE ROCK