'For Their Own Good': Civilian Evacuations in Germany and France, 1939-1945 9781845458164

The early twentieth-century advent of aerial bombing made successful evacuations essential to any war effort, but ordina

170 1 9MB

English Pages 280 Year 2010

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Contents

List of Illustrations

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Preparing for air war

2. Order or chaos

3. Organizing evacuation

4. Our stay gives us no pleasure

5. If only family unity can be maintainted

6. On the basis of selection

7. Responding to chaos

8. Evacuation's aftermath

Notes

Note on Sources

Bibliography

Index

Citation preview

“F T O G”

“For Their Own Good” Civilian Evacuations in Germany and France, 1939–1945

EEE

Julia S. Torrie

berghahn NEW YORK • OXFORD www.berghahnbooks.com

First published in 2010 by

Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com

©2010, 2014 Julia S. Torrie First paperback edition published in 2014 All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Torrie, Julia S., 1973– “For their own good” : civilian evacuations in Germany and France, 1939–1945 / Julia S. Torrie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-84545-725-9 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-78238-390-1 (paperback) -- ISBN 978-1-84545-816-4 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Evacuation of civilians—Germany. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Evacuation of civilians—France. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Aerial operations. 4. Bombing, Aerial—Social aspects—Germany—History—20th century. 5. Bombing, Aerial—Social aspects—France—History—20th century. 6. Germany— History—1933–1945. 7. France—History—German occupation, 1940–1945. I. Title. D809.G3T67 2010 940.53’16—dc22 2009025426 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed on acid-free paper ISBN: 978-1-78238-390-1 paperback ISBN: 978-1-84545-816-4 ebook

EEE

List of Illustrations

vi

Abbreviations

vii

Acknowledgements

viii

I

1

. P A W

13

. O C

31

. O E

50

. O S G U N P

73

. I O F U C B M

94

. O B S

128

. R C

151

. E’ A

167

Notes

181

Note on Sources

242

Bibliography

244

Index

261

EEE

1.1. Germany Threatened by Enemy Aircraft

23

2.1. German Soldiers Feed French Civilians

42

4.1. With Open Arms!

77

4.2. From the City to the Land

79

5.1. Gauleiter Hofmann in Baden

107

7.1. Evacuation Plan for Greater Cherbourg (25 Nov. 1943)

153

EEE

3.1. Projected Participants, Berlin and Hamburg KLV (27 Sept. 1940)

55

3.2. Designated German Reception Areas (19 Apr. 1943)

58

3.3. Designated French Reception Areas (4 Feb. 1943)

65

EEE

AA AN AD Calvados AD Cantal AD Eure AD Manche AD Orne AD Seine-Maritime ADP BA BA-MA C.O.S.I. DAF DDK DR GLAKHE HstAD IHTP J.O. LK PGDR NSV NSDAP SD S.I.P.E.G. Sopade StAM RSHA USSBS WLZ

Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes Archives Nationales, Paris Archives Départementales du Calvados, Caen Archives Départementales du Cantal, Aurillac Archives Départementales de l’Eure, Evreux Archives Départementales de la Manche, Saint-Lô Archives Départementales de l’Orne, Alençon Archives Départementales de la Seine-Maritime, Rouen Archives de Paris Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg Comité Ouvrier de Secours Immédiat Deutsche Arbeitsfront Dokumente deutscher Kriegsschäden Direction des Réfugiés Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe Nordrhein-Westfälisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Düsseldorf Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent Journal Officiel Interministerielle Luftkriegsschädenausschuß Ministère des Prisonniers, Déportés et Réfugiés Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei Sicherheitsdienst Service Interministériel de Protection contre les Évènements de Guerre Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands im Exil Nordrhein-Westfälisches Staatsarchiv, Münster Reichssicherheitshauptamt United States Strategic Bombing Survey Westfälische Landeszeitung

EEE

I

have received assistance on this project from many quarters. Above all, I would like to thank Charles Maier, David Blackbourn, and Susan Pedersen. All three have been unfailingly patient, critical, and encouraging as this work evolved from the original proposal into this book. Generous funding from various sources made the project possible. In particular, fellowships from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada supported a year and a half of archival research in France and Germany. This research was supplemented by shorter trips funded by the Krupp Foundation and the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University. The Center for European Studies also gave me ten months of financial support to finish writing. Since then, St. Thomas University has helped me attend several international conferences and given me release time from teaching to revise my work. I am grateful to the staff of the archives and libraries I visited in France and Germany, particularly for help in gaining access to restricted material. Without the kindness of individuals too numerous to name, important documents would have escaped my notice. As the project developed, a number of people gave me suggestions for further reading, hints on rough drafts, and moral support. Robert Gellately has encouraged and inspired me since my undergraduate years. More recently, Roger Chickering, Sarah Fishman, Peter Fritzsche, Marcus Funck, Susan Grayzel, Ulrich Herbert, Patrice Higonnet, Robert Moeller, Adelheid von Saldern, Nathan Stoltzfus, and Dominique Veillon have made valuable suggestions on different segments of the project. While in Berlin in 1999, I was able to join a Doktoranden Kolloquium at the Zentrum für Vergleichende Geschichte Europas at the Free University, under the supervision of Christoph Conrad. I would like to thank him and Gunilla Budde for helping to arrange my participation in the colloquium. On this side of the Atlantic, I am indebted to the members of the European History Graduate Workshop at Harvard’s Center for European Studies, particularly Rebecca Bennette, Eric Kurlander, and David Meskill, who read and commented on drafts of two chapters. The insightful comments of the participants in the Seventh Transatlantic Doctoral Seminar at the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, helped me turn a short paper into the Witten case study below. Other sections of the work have benefited from the wide-ranging knowledge

A E ix

of anonymous reviewers, panel participants, and commentators. In the last few years, my generous colleagues in the History Department at St. Thomas University have, often without knowing it, contributed expertise from their diverse fields to segments of the manuscript. My efficient research assistant Armin Musterle helped arrange permission to reproduce various images used in the work. The encouragement and support of many friends has been important. The Brinkmann family, in particular, has been kind and hospitable to me over many years. I am deeply grateful to my parents Amelia and James Torrie, my sister Catherine, Frédéric, Eloïse, and the rest of my family, all of whom have contributed in countless ways to the completion of this work.

I EEE

War everywhere necessitates interventions into the personal freedom of the individual in favour of the community. —Nazi Party representative in Düsseldorf, 19421 I can still keep my children wherever I want to. After all, they’re still my children. —German citizen’s anonymous comment, recorded by the Sicherheitsdienst, 19432

W

? At their most basic, they are wartime measures that save lives by removing non-combatants from vulnerable areas. Although they are essentially positive endeavours with a laudable goal, they challenge nations’ transportation and accommodation capacities, and require governments to intrude into the lives of millions of civilians. In many ways, evacuations are huge social welfare programs, for governments must convince people to leave their homes, transfer them to safer areas, and look after their financial, physical, and psychological well-being. Those involved in evacuations dislike them, because they banish unhappy city-dwellers to rural backwaters, provoke homesickness and unease, and turn one segment of the population into the unwelcome long-term “guests” of another. Most unsettlingly, evacuations divide families, sending children and mothers away to the countryside while other family members stay home to work. Societies at war must make choices: who will be evacuated, and where? How long will the transfers last, and how often will displaced individuals be able to visit their homes? Will popular preferences be allowed to determine any part of the process? Evacuations balance delicately on the borders between state paternalism, coercion, and public tolerance. Against a backdrop of war and occupation, evacuations offer a new forum to explore the interplay of Germany and France. These measures draw attention to the negotiated, improvised quality of the German occupation, an ongoing process that played itself out in the context of prewar relations and longer-term trends.

2 E C E G F, –

Evacuations in both countries show how civilians and governments interacted over policies that seemed necessary, yet were unwelcome and difficult to impose. Popular opposition to population transfers, which was rooted in family concerns, highlights the importance of the family as a source of noncompliance in authoritarian regimes. Evacuees’ refusal to toe the line limited the authorities’ exercise of power. Evacuations remained marked by the regimes sponsoring them, and though they appeared to be open to all French and German citizens, only well-behaved members of the “national community” were included. German and French war relief relied directly on the oppression of those who, like Jews, “asocials,” or the mentally ill, were not considered “worthy” of the state’s assistance. Evacuations became a privilege, not a right. Civilian evacuations began in late August 1939, just before World War II. French and German border populations were removed from their homes to make room for troop movements, limit exposure to enemy fire, and avoid occupation. Children and their mothers also left vulnerable cities in the interior. Preemptive evacuations continued throughout the war, although from the summer of 1943, population transfers in the wake of air raids became more important than those occurring in advance. Despite ongoing efforts to organize and direct evacuees, the improvised character of evacuations came to the fore as time went on. In France in 1940 and 1944, and Germany from mid 1944 onward, organized evacuations broke down completely as civilians fled before an advancing battle front. The massive, chaotic aspects of these events distinguished them from other evacuations, but at the same time they shared many characteristics of more orderly population transfers. All three types of evacuations—preemptive, reactive, and emergency—are considered here. Evacuations continued as long as the fighting did, ending in 1944 in France and 1945 in Germany. The war’s end left many evacuees far from home, with some unable to return to their native cities before several years had passed. The present study focuses on Germany and France during World War II, but also considers the prewar discourse on evacuation and, briefly, the postwar fate of evacuees. The German government estimated that nearly 9 million citizens had been evacuated by the state or had evacuated themselves as of 11 January 1945. This figure did not include special children’s programs that added at least another 2 million to the total. It also left out displacements between early January 1945 and the end of the war in Europe, in May. The true number of German evacuees was therefore probably upwards of 12 million. A year earlier, in January 1944, French authorities had counted about 1 million evacuees in France, although by August 1944, after battle had again swept through the country, there were as many as 2 million displaced individuals of all kinds. In 1940, as a result of the German Blitzkrieg advance, France had temporarily been swamped by at least 7 million displaced persons.3 Evacuations affected many millions of civilians in these two countries alone and were an integral, if little studied, part of the war experience.

I E 3

This book focuses on evacuations in two countries for several reasons. First, air war itself paid little attention to national boundaries, and since France was occupied by Germany for most of World War II, French evacuations cannot be elucidated without reference to Germany. At the same time, experiences in France helped shape measures inside the Reich. Before the war, policies in each country were molded by the perceived threat of the other. Later, during the occupation, German officials viewed the two areas as parts of one whole. National differences continued to influence evacuations in each country, but neither case can be fully understood without the other. The parallel development of evacuations in these two places sheds light on authoritarian states and their interactions with citizens, on the German occupation of France, and more broadly on FrancoGerman relations. In the interwar period, theorists in Germany and France began to consider how to respond to the air raids that would surely be a major part of the next international conflict. The French favoured evacuations to safeguard civilians’ lives, but Germans rejected these measures as cowardly flight. Instead, they preferred to fortify cities with shelters and flak guns, while strengthening urbanites’ resolve through civil defense training.4 In the years prior to World War II, civil defense policy came to be defined in national terms, and evacuations became the “French” response to an airborne threat, while the “German” alternative was to stand fast in the cities. The tendency to use the other country as a foil for one’s own attitudes continued during the war. When both nations began large-scale civilian evacuations, the prewar juxtaposition of “evacuating” France and “non-evacuating” Germany no longer applied. Germans sought a new model to explain the fact that the Reich also had started evacuating. Those who had witnessed the disorderly mass flight of civilians as Reich armies advanced into Belgium and France now identified individualism as the primary cause. Emphasizing the chaotic and individualistic aspects of the ill-fated French “exodus,” the Germans defended their own programs as foresighted, orderly, and rooted in the good of the community—thus, fundamentally different from the French. A secondary result of this new opposition was to raise the stakes of German evacuations, making it imperative that they actually be orderly and that the whole community participate in making them so. This, in turn, helps explain why popular opposition to evacuation measures, which skyrocketed from 1943, was treated as a great affront by the regime. Disobeying evacuation orders was a sign of individualism, a flaw that would lead to “French” chaos, and ultimately, defeat. The fact that policymakers in Germany and France interpreted evacuations through the mirror of their European neighbour makes it crucial to examine these nations in tandem. More concretely, evacuation policies in Germany and France draw attention to the complicated process of imitation, negotiation, ma-

4 E C E G F, –

nipulation, and subtle or less subtle pressure that defined relations between the two countries during the war, and especially during the occupation of France. Sources about evacuation show how French and Germans interacted over what was essentially a “positive” policy with a humanitarian goal, unlike the deportation of the Jews, or the compulsory labour service, which usually have attracted historians’ scrutiny. In order to explore these issues more deeply, I focus on one region of each country. In Germany, heavy bombing over densely crowded urban centers made evacuations an especially pressing concern in the Rhine-Ruhr industrial area. In France, Norman cities with German military installations, such as Le Havre, Cherbourg, and Caen, were targeted by the Allies as early as 1940. The bombing of Normandy continued throughout the war, only to escalate before the Allied Landings in 1944. Belying the comparatively limited extent of actual air war damage in France, large-scale preemptive evacuations of danger zones occurred, especially along the Atlantic and Channel coasts. These prophylactic measures, together with the destruction associated with the Allied Landings, make Normandy the best illustration of the French situation. It is worth noting that the Rhine-Ruhr and Normandy are not intended to be “typical” cases; rather, severe bombing in both places starkly exposed evacuations’ dilemmas. Policymaking tended to be driven by events in these regions, which had ripple effects beyond. More generally, the German and French situations discussed in this book were far from identical. Some 22 percent of Allied bombs were destined for targets in France, and the total number of civilian victims was about a fifth of that of Germany—wartime bombing killed 67,078 French civilians, while 305,000 Germans lost their lives in the same fashion. The British, for their part, lost 60,595 civilians to German bombs, slightly less than the French total.5 Though this work retains elements of a classic comparison of similarities and differences, it is primarily what Heinz-Gerhard Haupt and Jürgen Kocka have called a “relationship study.” The links between French and German civilian evacuations are the main focus as is the interplay of the two nations’ policies.6 Given the danger, and the nature of their regimes, one might have expected that German and French leaders would have had no trouble enforcing whatever evacuation policies they chose. In fact, there were strict limits on what they could demand. Careful negotiation took place between the requirements of the state and the needs of ordinary people, and official plans sometimes had to be altered in response to public protest. Successful evacuations were essential to the war effort, but a poor welcome in the reception areas, uncomfortable conditions, and homesickness made many people wish they had never left their native cities. Especially from the summer of 1943, unhappy evacuees returned from the reception areas without official permission. The authorities in both Germany and France opposed these returns with draconian measures, going so far as to deny ration cards to so-called “wild returnees” (wilde Rückkehrer).

I E 5

Left with little other recourse, civilians used family-based claims to protest government policies. Long-term evacuations threatened family ties, and citizens drew attention to the contradiction between Nazi rhetoric, which prized the family, and rigid evacuations that failed to take families into account. Family-based protest in Germany peaked in October 1943, when some 300 residents of Witten, in the Ruhrgebiet, demonstrated publicly against the denial of ration cards to “wild returnees.” The Witten citizens, and others who returned from the reception areas without permission, compelled the authorities to alter evacuation policies to make them more moderate and family-sensitive. Victoria de Grazia has shown that family concerns frequently underlay popular protest in Mussolini’s Italy. Because the regime placed such a high value on the family, questioning government family policies cast doubt on the regime’s ability to interpret what families really wanted, and at the same time, on its very right to rule. De Grazia uses the term “oppositional familism” to describe the attitudes that fed this kind of protest.7 A similar phenomenon was at work in Germany, where family-based opposition to evacuation measures tested the legitimacy of the regime. Perhaps paradoxically, although evacuations in occupied France were more often compulsory than in Germany, and although French civilians returned home without permission fairly regularly, no open anti-evacuation demonstration like the one at Witten took place. Fear of reprisals may have held some French civilians back, but since hundreds of public demonstrations, mainly against food policy and the compulsory labour service, did occur during the German occupation, an alternate explanation for the lack of French anti-evacuation protests must be sought.8 In part, frustrations over evacuation policy were less volatile in France because fewer people moved away from home and because evacuations tended to be shorter in duration. When there were disagreements over evacuation, notably between the population and the occupation forces, the French government usually interceded, acting as a buffer to absorb tension and negotiate compromises. This buffering role headed off widespread popular opposition to evacuation measures. The most important reason for the French population’s comparatively calm acceptance of evacuation measures, however, was that even under the occupation, French policies took families more into account than German. An albeit sometimes overdrawn distinction between a German emphasis on community and a French emphasis on the family played itself out through the war and occupation, helping to smooth over French civilians’ dislike of evacuation measures.9 Evacuations highlight the power of family-based grievances as a source of opposition in authoritarian states and underline the importance of family concerns in the ongoing dialogue between individuals and government. On the surface, evacuations appeared to be universally available to endangered French or German citizens. In fact, the humanitarian thrust of the measures was

6 E C E G F, –

deeply marred by the exclusion of many individuals living in Hitler’s Europe. Evacuation policies overlapped with, and indeed were closely connected to, the racialist and eugenicist programs of the Third Reich. Jews and others who did not belong to the Volksgemeinschaft were not evacuated, and each space this left on trains to rural areas allowed another person, who was a member of the “national community,” to be borne away to safety. In addition to Jews and other “race enemies,” neither the mentally ill, nor so-called “asocials” were considered for evacuation. Any person whose behaviour in the reception areas aroused suspicions of immorality or criminality was sent home. There were additional connections between war relief measures and the oppression of those outside the “national community.” The apartments of deported Jews in France and Germany became housing for bombed-out families. Spoliated furniture was not only shipped across Europe to furnish the offices of the Wehrmacht in the East, but also redistributed locally to bomb victims.10 Psychiatric patients were moved out of urban hospitals so that these facilities could be converted to emergency medical use. By evacuating only “desirable” members of the “national community,” German, and to a lesser but still considerable extent, French authorities, effectively made Allied aerial bombardments serve their own racialist and eugenicist ends. To date, civilian evacuations have been studied mainly in a democratic context, one country at a time. In Britain, Richard Titmuss long ago opened the subject to scholarly scrutiny, but evacuations remain under-researched elsewhere.11 Recent works on the German situation by Gerhard Kock, Michael Krause, and Gregory Schroeder are signs of a growing interest in the field. Kock’s study of the Kinderlandverschickung (KLV), a program specifically for children, argues that the goals of German children’s evacuations lay as much in the indoctrination and formation of young Nazis as in the preservation of their lives. Krause, for his part, identifies the evacuees as a population pressure group, and, focusing on their demands after the end of the war, places them in the context of other temporarily homeless groups, like the refugees of the former German territories in Eastern Europe. Gregory Schroeder likewise examines the postwar period, highlighting arguments evacuees employed in order to speed their return home.12 Beyond these authors, however, research on Germany is limited to small-scale local studies that do not consider the broader implications of civilian evacuations.13 In France, where air war is rarely discussed, historians have focused on the socalled population “exodus” as the Germans advanced in 1940, or described the travails of citizens evacuated and later exiled from occupied Alsace-Lorraine. The Liberation is another carefully chronicled moment of the war in France, and local histories typically mention civilians’ accompanying displacements. Comprehensive works on German occupation and life on the Home Front sometimes refer to evacuations in passing, but none of these studies analytically treat them as a separate subject.14

I E 7

The present work speaks to three specific areas of the vast historiography of war and authoritarianism. First, exploring evacuations contributes to our understanding of the civilian experience of total war, and air war specifically. Second, evacuation measures help elucidate the interaction between ordinary people and authoritarian governments in wartime, as well as the twin issues of popular consent and opposition. Finally, these measures can be used as a lens to bring the German occupation of France into better focus, emphasizing the ground-level interaction of French and German authorities, and bringing Germany back into a historiography that tends to downplay the conqueror’s side of the occupation. The civilian war experience usually has been defined by how urban adult citizens dealt with the traumas of war, but evacuations also draw attention to children’s experiences. For civilians, especially children, transfer to another region of their country for months, or even years, constituted a significant wartime hardship. In addition, evacuation documents shed light on rural life in wartime and the complex urban-rural encounter of evacuees and their hosts.15 Allied air raids and their impact on civilians play a central role in renewed debates about Germans as perpetrators and victims. These debates, which are connected to larger questions about war and memory, typically focus on aerial bombardment itself, leaving evacuations to the periphery.16 Yet evacuations were longer lasting, and defined civilians’ war experience as much, if not more, than the air raids themselves. These measures, which play such a central role in British memories of wartime, are almost absent from the public record in Germany and France. In France, debates about perpetrators and victims are not linked to air war, but rather to the larger issue of collaboration versus resistance during the occupation. The present study highlights the importance of evacuations for these discussions, not only because the measures were an integral part of the war experience, but also because they emphasize the persistent overlap between the categories of victim and perpetrator. Evacuees were both war victims and at the same time, as outlined above, consenting beneficiaries of state policies that oppressed those not considered to be part of the “national community.” Civilians’ reactions to evacuation are strong indicators of wartime morale, which itself was related to the degree of popular consent for the domestic and foreign policies of the government.17 The issue of consent, not only during the war, but also at peace, has long been one of the most compelling questions about the Third Reich. While some scholars have stressed the roles of terror and ideological conformity in limiting popular opposition to the regime, others, such as Ian Kershaw, have emphasized the importance of propaganda and the cult of the Führer in bolstering consent. Without supporting Daniel Goldhagen’s extreme formulation that Germans were “Hitler’s willing executioners,” historians such as Robert Gellately have highlighted the breadth of grassroots support, especially for the negative and repressive policies of the Nazi regime.18

8 E C E G F, –

Like mass employment schemes, or marriage bonuses, evacuations helped maximize citizens’ approval for the regime and masked the authorities’ less attractive policies. Evacuations gave civilians the impression that the government was looking after their welfare and became a vehicle for integrating ordinary people into the “national community.” At the same time, these population transfers gave the authorities an entré into normal families, families that might otherwise have remained relatively sheltered from the state’s intrusions. This state presence, along with the mutual surveillance of hosts and evacuees, encouraged conformity with the policies of the regime. The consent-bolstering function of mass organizations like the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Workers’ Front) or the Légion Française des Combattants (French Veterans’ Legion) is well-recognized, but historians have paid less attention to the integrative role of charitable organizations, which played a crucial part in tying the population to the government, especially in wartime. Although much of the assistance evacuees received came from the state, “para-governmental” charitable organizations were also instrumental. In Germany, the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (NSV) assisted destitute and traumatized evacuees. In France, the Secours National and the Comité Ouvrier de Secours Immédiat (C.O.S.I.) stepped in. These groups, positioned between ordinary people and the state, provided assistance while also supporting the government and helping to demonstrate its concern for people’s well-being. Their programs to boost morale and consent among a particularly sensitive portion of the population, evacuees, were essential to the Axis war effort.19 Evacuations thus allow us to explore questions about consent, dissent, and opposition, which, for all that they have been asked before in other contexts, remain pertinent to our understanding of the citizen’s role in authoritarian states. Kershaw’s work on the Bavarian crucifix campaign and Nathan Stoltzfus’ on the Rosenstrasse protest show how popular noncompliance sometimes hampered the Nazi regime’s exercise of power.20 Evacuees who protested at Witten in 1943 probably ran a lesser risk than the women of the Rosenstrasse, but their action was another example of the limited dissent or opposition known in Germany as “Resistenz,” to distinguish it from the more formal, premeditated “Widerstand.” These terms remain contested, but I have followed Ian Kershaw’s suggestion that, in English, “opposition” may be used to describe actions “not directed against Nazism as a system and at times deriving from individuals or groups at least partially sympathetic towards the regime and its ideology.”21 Chapter five discusses in greater detail the extent to which the evacuees’ protest at Witten actually threatened Hitler’s regime. At the very least, evacuees’ refusal to go along with the regime’s plans forced a significant re-evaluation of evacuation policies. Even if the evacuees did not see their opposition as a political act, the regime interpreted it as such, for the leaders understood that unpopular evacuation measures might have a devastating effect on morale.22

I E 9

In France, because many (though by no means all) evacuations were ordered by the Germans, evacuees’ low-level opposition may seem to fit directly and unproblematically under the rubric of resistance.23 In fact, however, French opposition to German-ordered evacuations arose from a basic sense of outrage that citizens were being asked to leave their homes and was no more “formal” than that of German citizens. There have been efforts to make a kind of “Resistenz” versus “Widerstand” distinction in France, as in Germany, yet even when French authors write of what they have called “resistance-movement” (François Marcot) or “peri-resistance” (Michel Boivin and Jean Quellien), they often take it to be dependent on, and conditioned by, the “real” resistance of the major movements. Disorganized, apparently random, and popular noncompliance tends not to be studied on its own terms in France.24 The issues of consent and opposition, on a national scale, are inevitably associated with the study of military occupations. In France, historians have generally asked questions that are less about individuals’ consent for, or opposition to, the Vichy regime per se, than they are about the degree to which France as a nation consented to, and collaborated with, German rule. Robert Paxton, by insisting that the years 1940 to 1944 should not be treated as an aberration, but rather, were intimately linked to the broader history of France, demonstrated that the occupation was more than just an unwelcome imposition and that many French welcomed Hitler’s promise of renewal. Paxton’s work examines Franco-German interaction primarily on the level of government and diplomacy, but other scholars have since drawn more attention to ground-level French responses to the occupation and to the Vichy regime itself. In the 1990s, a new emphasis on women’s attitudes toward the regime helped to round out the picture of French society during the occupation.25 Philippe Burrin has suggested, however, that the departure from pre-Paxtonian interpretations, which viewed France as the victim of German domination, toward the study of Vichy on its own terms, has tended to minimize the role of the Germans in occupied France. “In the past,” Burrin writes, “the German presence tended to block our view of the horizon. Today, Germany appears as a faint shadow in the background, while Vichy occupies center stage.”26 The present work brings Germany back into the picture, placing occupied France in the larger context of Hitler’s Europe and French-German interaction both before and after the war. It draws attention to the ground-level interplay of French and Germans, highlighting the dynamic, negotiated quality of the occupation, something both parties were making up as they went along.27 In the text, I have used the words “evacuee” and “evacuation” to refer to civilian transfers that took place in France and Germany during World War II. The term “evacuee” is preferable to “refugee” for several reasons. Evacuation emphasizes that people were deliberately displaced, as part of a conscious government policy. Becoming a refugee, on the other hand, implies that an accidental confluence of

10 E C E G F, –

events led individuals to flee. Refugees, moreover, tend to have crossed a national border, whereas evacuees are displaced within their own country. The boundaries of usage between the words remain fluid, however, and it is often difficult, in practice, to distinguish between the two categories. Not all evacuations were planned, for aerial bombing and land invasion led to both preemptive measures and spontaneous flight. Not all evacuees remained within their country of origin, for some Germans were evacuated as far afield as the Netherlands or Hungary, and in 1940, Belgians as well as French civilians fled southwest through France as the Germans advanced. In some cases, therefore, the terminology may be interchangeable; but, for simplicity’s sake, I have used evacuation and evacuee throughout. A clear distinction between the two words is further complicated by the challenges of translating primary sources into English. The word réfugié is used commonly in French documents to refer to individuals who would be better described as “évacués,” for they stayed within the country and were removed from vulnerable cities as a result of conscious government policies. French bodies, like the national and departmental bureaus responsible for evacuees, Directions des Réfugiés, bear titles reflecting this usage, which I have retained. As the French terminology implies, evacuees were viewed in France as a smaller subset of the category of réfugié, which meant any person displaced by war or natural disaster. This was partly because there were a smaller number of true “evacuees” in France moved by the government, compared to the group of citizens who spontaneously fled endangered areas. It was also a sign of the continuities between early wartime measures meant to help these civilians, and policies already in place, notably to assist refugees of the Spanish Civil War who had been living in France since the 1930s. In Germany, on the other hand, evacuees were a category unto themselves, but one that rarely was called by its name. Because evacuations were adopted with reluctance by the Nazis, they used a variety of euphemisms to disguise their nature and to imply that German evacuations were different from those taking place elsewhere in Europe. Instead of evakuieren, the regime preferred umquartieren (reaccommodate, quarter elsewhere). This term, as Michael Krause has pointed out, emphasized the temporary, provisional quality of the measures.28 It echoed military vocabulary and was meant to suggest that German evacuations were orderly, deliberate, and well-managed. In late June 1943, the German authorities announced that for consistency’s sake, the noun Umquartierung should replace Evakuierung entirely.29 By this time, Evakuierung had fallen further out of favour because it had come to be used to describe the deportation of the Jews and others to concentration camps.30 Clearly, it seemed inappropriate to use the same word to describe both deportations and the transfer of vulnerable members of the “national community” to safer areas of the Reich. This book is organized comparatively throughout. It begins with an exploration of the discourse on civil defense in Germany and France in the interwar period, analyzing how France became a country that favoured evacuations, while

I E 11

Germany opposed them. The first chapter examines the distinction between “evacuating” France and “non-evacuating” Germany, and traces the effect of this opposition on planning for air war prior to 1939. Chapter two explores flawed evacuations on both sides of the Franco-German border in 1939 that were an early sign of the trouble such measures could cause. After a quiet winter, the German spring campaign provoked the flight of millions of civilians through Belgium and France, leaving contemporaries with indelible images of chaos and disorder. The Third Reich’s theorists had claimed that large-scale civilian evacuations would not be necessary in Germany, but when aerial bombing increased there in the early fall of 1940, they too began removing children from major cities. This chapter shows how the Germans used France’s disorderly “exodus” to justify and explain their change of heart. They replaced the old model of “evacuating” France and “non-evacuating” Germany with a juxtaposition of French chaos and German order, thereby endowing evacuations in Germany with such symbolic weight that absolute order had to be maintained throughout the war. The third chapter outlines the organizational structure of evacuations, describes a typical evacuation, and examines the contributions and interaction of the paragovernmental organizations NSV, Secours National, and C.O.S.I. It takes the reader to the end of 1942 and shows how evacuations evolved as aerial bombardments changed. This chapter paints a picture predominantly of successful evacuations. The following chapter takes up the many problems that evacuations caused. Frosty welcomes in the reception areas, regional and religious differences, homesickness, and the potential threat of moral lapses were problems identified by the authorities and experienced by the evacuees. The fourth chapter considers how French and German regimes tried to respond to these difficulties, which grew to a crisis point by the fall of 1943. It also explores the reactions of the evacuees themselves, ranging from resignation, through dismay and complaint, to disobedience and departure for home. Evacuees’ reactions are taken up in greater detail in chapter five, which uses two case studies, of Witten (Germany) and Cherbourg (France), to illustrate key aspects of the interaction between civilians and authoritarian states at war. The Witten case study examines a public anti-evacuation demonstration that occurred in that city in October 1943, while the study of Cherbourg analyses French reactions to a German-ordered evacuation of over 70 percent of the population. At Witten, family-based concerns led to open opposition, while Cherbourg’s compulsory evacuations were moderated by greater consideration of the family, and this, combined with the buffering role of the French state, headed off major conflict. Chapter six details connections between the evacuations of those included as full members of the community and the oppression of those who were not. It looks at Jews, the mentally ill, and “asocials,” and shows that German and French policies to help civilian war victims not only excluded, but were in many cases actually founded upon, the oppression of these groups.

12 E C E G F, –

The next chapter traces the increasing breakdown of evacuation systems as the war came to a close. Orderly evacuations depended on relative stability on the battlefield, and, when the war turned against Germany, they began to fall apart. French civilians caught in the fighting accompanying the Liberation took refuge wherever they could—in farmhouses, churches, even in disused quarries. In Germany, the authorities’ reluctance to recognize the gravity of the situation meant that civilian evacuations were left to the last minute, and, especially in the East, became a mad scramble to safety. Many evacuees who had been transferred from the German heartland to shelter from Allied bombardments now found their erstwhile refuges overrun by the Red Army. They took to the roads with whatever they could carry, and the much-vaunted orderly German evacuations came to an end. As the Reich fell apart, each individual sought only to save his or her own skin. The book’s final chapter looks at evacuees’ situation once the war was over. Since there were so many others clamouring for government assistance in Germany and France, evacuees’ repatriation was far from being a top priority. Evacuees had to capture the authorities’ attention, and they did so by insisting that they had “right” to return home and obtain housing, by emphasizing their status as victims of war, and by exploiting contemporary preoccupations with family health and welfare. In a postwar climate where fostering social justice, caring for war victims, and strengthening the family were key concerns, evacuees used vulnerability and victimhood to make powerful claims for basic rights. The end of the war made obvious the limitations of civilian evacuations. Not only did evacuations use resources that could not be spared if the situation was truly critical, but they also relied on the cooperation of individuals who would only play along if they felt the state could guarantee their safety and happiness better than they themselves could. War may demand sacrifices, but if the sacrifices people are asked to make are too far-reaching, if what the Nazi Party’s representative in Düsseldorf called the “interventions into the personal freedom of the individual in favour of the community” are too great, the system falls apart. Civilian evacuations in Germany and France expose this conundrum well. These evacuations were both a means of saving millions of civilians’ lives and an integral part of Hitler’s brutal regime. Ostensibly positive measures, they were disliked by most of the people who participated. Voluntary on the surface, they were often compulsory by virtue either of circumstances or of government orders. A vehicle for encouraging consent by showing the regime’s concern for civilians’ welfare, they could also serve as a catalyst for opposition. Evacuations separated spouses, carried urbanites far from their homes, and kept children away from their parents for months, or even years. These many ambiguities make understanding civilian evacuations crucial to our comprehension of state and society at war.

P A W EEE

By virtue of [air power], the repercussions of war are no longer limited by the furthest artillery range of surface guns, but can be directly felt for hundreds and hundreds of miles over all the lands and seas of nations at war. No longer can areas exist in which life can be lived in safety and tranquility, nor can the battlefield any longer be limited to actual combatants. On the contrary, the battlefield will be limited only by the boundaries of the nations at war, and all of their citizens will become combatants, since all of them will be exposed to the aerial offensives of the enemy. There will be no distinction any longer between soldiers and civilians. —Giulio Douhet1

W

about the possible impact of air power, Italian Giulio Douhet imagined scenes of unlimited carnage. Traditionally, home was a peaceful refuge, but airborne weaponry widened the battlefield and blurred the lines between home and front, combatant, and civilian. Since World War I had left contemporaries with little doubt that the next war would be in large part an air war, the interwar period was characterized by wide-ranging debate about the form of such a war and the anticipated gravity of its outcome. Contemporaries discussed military and strategic issues, such as how and when to use aircraft, and whether or not to build independent air forces. Realizing that air war would affect a nation’s whole territory, they struggled to find ways to protect civilians from aerial bombardments. Some thought that anti-aircraft guns and bomb shelters would suffice, while others maintained that pre-emptive evacuations of certain parts of the population would be necessary. Debate about these issues was especially prevalent in Germany and France, for both nations had good reason to be concerned about aerial attack and each viewed its neighbour as the most likely potential aggressor. French and German authors shared many concerns about air war, but especially as the 1930s drew on, their opinions about how to protect civilians from

14 E C E G F, –

aerial attack diverged. German theorists increasingly argued that shelters and flak guns would constitute sufficient protection for the population and that large-scale evacuations would be unnecessary, even dangerous. Their French counterparts, on the other hand, favoured pre-emptive evacuations of at least some parts of the population to minimize panic and save lives. Given that the goal of policymakers in both countries was to protect civilians without compromising the war effort, why did such a difference of opinion develop? How did it come to be mapped out along national lines, with French theorists favouring evacuation, while Germans rejected it? Past experiences of war, differing ideological orientations, and divergent notions about the rights of the family and the individual versus the demands of the nation at war helped create opposing views. These differences had clear effects on policymaking leading up to the outbreak of war and continued to influence the progress of evacuations once hostilities began. French and German ideas about air war were heavily influenced by Douhet, the pre-eminent interwar theorist of this form of warfare. In The Command of the Air, Douhet argued that the full potential of new airborne weapons could only be realized if the aerial branch of the military were liberated from existing land and naval branches. The small-scale strategic use of airplanes in World War I should give way to a new form of warfare tailored to fighters’ and bombers’ ability to cross national boundaries and fly over enemy defenses with ease. Once an aggressor’s airplanes had entered neighbouring territory, Douhet believed that attempts to defend against them would be futile. Vigorous aerial offense was the only way to protect a nation against air attack. Although Douhet overestimated the offensive potential of aerial weaponry, his conviction that it was impossible to mount an effective defense against airplanes led to a widespread belief that a sudden air strike would open the next war, and decide it within a matter of days. In the war of the future, no homeland would remain inviolate, no citizen would be spared, and civilians would become, like soldiers, the defenders of a ubiquitous front line.2 Douhet’s apocalyptic vision resonated forcefully with his contemporaries. Air attack was an uncanny and disturbing prospect, and the interwar period saw several attempts to limit the targeting of civilians. Between 11 December 1922 and 6 January 1923, a commission of international jurists met at The Hague, hoping to draft a set of rules for aerial warfare. After extensive discussion, no consensus could be reached. A particular sticking point was Art. 24 of the draft accord, which contended that, “aerial bombardment is legitimate only when directed at a military objective.”3 Certain restrictions had been placed on aerial warfare at The Hague peace conferences of 1899 and 1907, but now that the capabilities of the new technology were more apparent, few powers were willing to limit its use. Other meetings, including the 1932–34 Geneva Conference, saw further attempts to come to an agreement, and there were proposals to prohibit aerial bombardments entirely, but no consensus was reached and World War II

P A W E 15

began without an international convention to govern the legitimate use of aerial weaponry.4 These discussions’ failure to limit substantially the targeting of civilians, combined with growing awareness of air war’s implications for industrial production and morale, led to increased consideration of the offensive and defensive aspects of aerial warfare. By the early 1930s, two schools of thought had begun to emerge regarding air raid protection. One point of view held that building air raid shelters and anti-air raid defenses around major cities would suffice to safeguard civilians, industrial, and military targets. Drastic measures, like evacuating the population, were impractical and would be unnecessary. The opposing attitude was that flak installations and air raid shelters might be useful, but large-scale evacuations of civilians and industrial resources would have to be undertaken regardless. Alfred Giesler, a senior German civil servant, was a proponent of the first viewpoint. In a 1930 essay in the air raid protection journal Gasschutz und Luftschutz, he examined the evacuation question.5 Giesler noted that, “opinions are very divided over precisely this issue. [But] a closer examination … will reveal that the evacuation [Räumung] of cities will remain a wish that can only be fulfilled in the most exceptional of cases.”6 Giesler argued that the challenge of transporting large numbers of elderly citizens, children, and other “superfluous eaters”7 out of a city would not be the main problem; rather, housing and feeding these individuals once they had left their homes was the real stumbling block. Displacing large numbers of people in wartime might threaten the economic, social, and even familial order; for “in many cases [evacuation] would lead to the ripping apart of the family, the germ cell of the state.”8 Giesler admitted that essential government offices, hospitals, and prisons probably would have to be moved to safer areas, but large-scale evacuations of urban residents would be impossible. The opposing view, that pre-emptive evacuations were necessary and presented the best way to save lives, was put forward by French General Paul Vauthier. Vauthier believed that, “Before aerial attacks occur, one should seek to protect against them through two series of measures; first by evacuating the population of large built-up areas, then by assuring its special education against the aerial menace.”9 For Vauthier, pre-emptive measures would limit casualties and diminish the chances of mass panic. An enemy seeking to damage morale would be unable to do so, and nervous crowds would not hamper the defense of military or industrial installations.10 Vauthier also contended that evacuations of some kind were probably inevitable, so it would be wise to plan ahead. He noted that despite the Italian’s faith in aggressive aerial defense, Douhet had postulated that air raids would provoke mass flight from urban areas. In order to understand this, Douhet had suggested that one only needed to think of the classic schoolmaster’s question: if a hundred sparrows are perched in a tree, and a hunter shoots ten, how many sparrows remain? The answer, of course, is none, since any healthy sparrow flies at the sound

16 E C E G F, –

of the first shot. People are not sparrows, but they are equally likely to take flight the moment their lives are in danger.11 Rather than leave an improvised escape to nature and chance, Vauthier recommended establishing a flexible departure scheme for half to three-quarters of the population, mainly women and children. Enough people must be left in the town to assure basic public services and policing.12 Such a plan, along with a comprehensive program of public education aimed at diminishing fears of air raids and teaching people what to do during a bombardment, would go a long way toward preparing the nation for a future war. The views of Giesler and Vauthier illustrate the two poles of the interwar debate on aerial defense, and more specifically, on evacuation. Giesler favoured more active types of defense, suggesting that planning for evacuations was neither practical nor worthwhile. Vauthier argued that states should prepare for all eventualities, including evacuations, since they were likely to happen anyway. The sooner good plans were made, the less likely was panic to ensue. The reader may have noted that Giesler, who argued against evacuation, was German, and Vauthier, who argued for it, was French. This points to the most prominent feature of the interwar debate about air raid protection. Evacuation was accepted much more readily as a means of civil defense outside Germany than within it. The German anti-evacuation position crystallized gradually over the 1930s, while France remained the primary champion of evacuation as a precautionary measure. With time, a pro-evacuation stance came to be seen as innately “French,” while an anti-evacuation viewpoint was perceived as “German.” There were several reasons why French and German authors disagreed about the advisability of evacuations. Each country’s past war experiences, ideological orientation, and ideas about the rights of families and individuals in wartime had a role to play. The discourse in each nation arose in the context of the other, and views across the border were used as a foil to defend policies at home. To its friends, a “French” approach meant experienced-based, liberal-republican, family-oriented planning. To its enemies, it meant excessive individualism and disorder. Those who favoured “German”-style policymaking, on the other hand, construed it as a forceful way to guarantee the survival of the “national community.” Its detractors viewed it as militaristic, authoritarian, and unrealistic, given the circumstances of modern warfare. In both countries, the experience of World War I was important for the development of civil defense policies. France had felt the full force of the Great War’s most brutal battles. Civilians had been removed from, or had fled, battle zones, and the French were well aware that large-scale clearing of territory might have to be repeated.13 The German occupation of Belgium and Northern France had been harsh, and French civilians had no desire to submit to German domination again.14 Even the quite limited air raids of World War I had required the full-scale evacuation of Dunkirk, and people independently had left other bombed cities. In the summer of 1918, when Paris was particularly endangered, 75,000 children

P A W E 17

went to rural family placements organized by the national Service des Enfants Assistés (Office of Assisted Children).15 Modern planes extended the battlefield further, and the French recognized that air war had turned the old model on its head—instead of sheltering defenseless civilians, as they had for centuries, cities were now the most vulnerable parts of the country.16 Germany, for its part, largely had been spared evacuations in recent years. Münster police major Eggebrecht noted that evacuations had seldom been discussed in Germany because they were expensive and difficult to organize. “Besides,” he wrote, “we Germans have had little experience in this area.”17 The major exception, Eggebrecht noted, occurred in East Prussia in 1914, when at least 800,000 people, mainly peasants, fled before the Russian advance.18 Later, toward the end of World War I, western cities like Karlsruhe were subjected to aerial bombardment, and small-scale spontaneous evacuations took place.19 German evacuations in World War I were minimal, though, which made theorists less attuned to the difficulties such measures might pose. German civil defense developed gradually in the 1920s. Although the treaty of Versailles limited anti-air raid weaponry and denied Germany an offensive air force, permission to engage in land-based aerial defense preparations was granted in 1926. The country’s domestic and foreign policy situation remained delicate, and partly for this reason, civil defense was assigned to the Ministry of the Interior, rather than the Ministry of Defense. Harkening back to a Prussian law from 1794 giving responsibility for local security to the police, police authorities were put in charge of defensive measures. This was in keeping with the widespread view that civil defense was primarily a problem of crowd control and panic avoidance.20 In July 1931, the Reich Ministry of the Interior issued a first formal set of civil defense guidelines. A number of especially vulnerable cities were declared Luftschutzorten (air raid protection towns), in an attempt to make civil defense a top priority in these communities. Municipal staff, fire departments, ambulances, and the Red Cross were to assist the police in carrying out their defense duties. The new guidelines stressed protecting essential industries from air attack and called for increased public education about air raids. Alongside the official regulations, a number of private civil defense organizations were created in the late nineteen-twenties and early nineteen-thirties to raise public awareness and encourage local preparedness.21 Hitler came to power on 30 January 1933, and three days later, made Hermann Göring Reichskommissar für die Luftfahrt (Reich Commissar for Aviation). Civil defense became Göring’s personal responsibility and then became the responsibility of the Reichsluftfahrtsministerium (Reich Air Ministry), created in May 1933. According to Erich Hampe, who was active in civil defense throughout this period, into the war, and beyond, this change was an attempt to ensure that civil defense kept pace with the latest tactical and technical developments in aviation. Moreover, Hampe noted, “Leadership and direction of civil defense

18 E C E G F, –

from the military sector had the advantage of providing better support for staff development, better provision of raw materials, greater availability of funds, and allowing for the use of military test-sites for [civil defense’s] own tests in the fields of building construction, decontamination, etc.”22 This was surely true, but putting civil defense under the control of the new Air Ministry also placed it under the direct supervision of one of Hitler’s closest associates. In a brand new ministry, new appointments could be made, and there would be no need to win over the stuffy bureaucracy of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. Assigning civil defense to a completely new government body was a sign of the importance the regime accorded this field. Historian Peter Fritzsche has argued that the discipline required for effective aerial defense appealed to the Nazis, who used the threat of bombardments to extend a military mindset to civilians.23 Effective air raid protection required the participation of the whole Volksgemeinschaft, and demonstrations and drills created the sense of a strong, renewed nation, ready for future challenges.24 Air raid preparedness already had been an important preoccupation in the Weimar period, but the Nazis elevated it to a national duty. To encourage air raid preparedness, the hugely popular Reichsluftschutzbund (Reich Air Defense League) was created in 1933 by joining together various preexisting organizations. It gained a monopoly over the field of civil defense and was dominated by a coterie of men around Air Minister Göring. By 1936, the League boasted 8.2 million members—one sixth of all Berliners, and over 10 percent of the population of Hesse, the Palatinate, and Baden, areas perceived to be especially vulnerable because they were easily accessible to French (and Allied) aircraft.25 The League published an illustrated tabloid, Die Sirene, which, by February 1935, claimed to be Germany’s fourth largest 20-pfennig newspaper.26 The League’s active, energized, and belligerent air raid preparedness was congruent with Nazi ideology and contrasted with French défense passive. Observers both inside and outside of Germany noted that civil defense modeled on police and military discipline could help off-set Germany’s vulnerability without an offensive air force.27 Dynamic Nazi Luftschutz made no allowance for evacuations, which seemed to imply retreat, or even flight. According to propaganda, German citizens, regardless of gender or age, did not run away. Instead, they stood fast behind flak guns, doused fires with buckets of water and sand, and brought children to the safety of well-built shelters. In Hitler’s Germany, “Evacuation from the cities had to be avoided at all costs, not simply because it was technically infeasible, clogging roads and straining suburban resources, but also because it upended civil repose, threw people helter-skelter into the streets, ripped apart families … and thus induced individual selfishness and defeatism. It was the end of a defensible society.”28 Still, the radical anti-evacuation stance adopted by the Nazis was not the only viewpoint expressed in Germany. Gasschutz und Luftschutz, a more serious air

P A W E 19

raid protection journal than the Reich Air Defense League’s Die Sirene, weighed the pros and cons of evacuation measures. Beginning in 1935, Gasschutz und Luftschutz printed a series of articles by authors Nagel and Teschner favouring evacuations and examining their viability.29 These articles suggested, for instance, that 20–22 percent of a city’s population might have to be evacuated, figures that are similar to contemporary estimates elsewhere.30 Evacuations should be voluntary and local, Nagel and Teschner argued, and advance planning would be the best way to avoid chaotic mass flight. In October 1936, Gasschutz und Luftschutz concluded its special feature on evacuations. Six months later, however, a curious addendum was published, in which retired artillery general Grimme, honorary president of the Reich Air Defense League, and Germany’s “oldest pioneering champion of air raid protection,” attacked the cautious pro-evacuation stance of the earlier articles.31 Grimme informed his readers that agreement had yet to be reached regarding the value of evacuations. He explained that: Two views are juxtaposed here: the French, that understands the evacuation of cities to be an essential part of all air raid protection measures, and has already found legal expression in French evacuation laws; versus the German, that holds that so much will be demanded of all parts of the population in terms of aerial defense activities that almost no one will remain for transport away from the cities.32

Grimme believed that the mass evacuations postulated by French authors and enshrined in French law would be impossible, and chaos would result. He used arguments based on supposed “national character” to contrast a “French” perspective that favoured evacuation with a “German” one that did not. To support his position, Grimme underlined the “emotional burden” of evacuations, arguing that “the mother, for example as air raid warden or lay helper, will do her duty more steadfastly, perhaps even more passionately, when she has her children and aged parents, or her sick family members with her, and can help them directly.”33 For Grimme, evacuation equalled running away, and for this reason, he argued that, “the word evacuation [Räumung] as a civil defense measure should disappear from the air raid protection vocabulary of the German people.”34 Evacuation might be acceptable for other peoples, Grimme implied, but not for Germans.35 Instead of spending money on a grand expression of national cowardice, German leaders should focus on practical training in air raid protection, and above all, the “moral education of the people to [its] duties, which reach their pinnacle in a hard, enduring will to resist unto death.”36 Grimme’s emphasis on fighting to the death for the Volksgemeinschaft, regardless of cost to individuals, and his privileging of ideology over a realistic assessment of the situation, are typical of the discourse about air raid protection among those closest to the Reich Air Defense League and Air Minister Göring.

20 E C E G F, –

The publication of Grimme’s article appears to have been imposed on the editors of Gasschutz und Luftschutz. The editors wrote in a preface to the piece that, “Although the question ‘to evacuate or not to evacuate’ has been dealt with thoroughly in Gasschutz und Luftschutz … the editors did not feel that they could withhold from their readers the … views of the oldest pioneer of civil defense in Germany, honorary president of the Reichsluftschutzbund, retired artillery General Grimme.”37 Instead, they tried to distance themselves from Grimme’s views and went on to insist that after this article, evacuation would be shelved. The treatment of evacuation in Gasschutz und Luftschutz reinforces Fritzsche’s claim that ideological, rather than practical, concerns fed the obsession with air raid protection in the Third Reich. Open debate about the advantages and disadvantages of civilian evacuations was silenced by Grimme’s article because the party maintained that Germans stood fast. Grimme’s work also shows how national character arguments were used to support a particular stance on the evacuation issue. Grimme proposed authoritarian, community-oriented civil defense, congruent with what he considered to be the traditional values and strengths of the German people. At the same time, he repudiated the democratic flexibility of the pro-evacuation French model. French commentator Henri le Wita also distinguished “French” and “German” attitudes, but he considered this distinction overplayed: You will often hear it said that there exist two methods of civil defense in the world…. One is said to be German, and advocates resistance at the scene in accordance with the temperament of our neighbours on the other side of the Rhine, who have an innate taste for discipline. The other is said to be French, founded on displacement, dispersal, organized flight. Ours [the French] is considered to conform to the individualism of the race that has worked such wonders in favour of liberty.38

According to Le Wita, French contemporaries’ conviction that ultra-organized civil defense was impossible in France merely encouraged lax planning. As he saw it, “There are not two ways to protect oneself, the one German, the other French. There is just one, and it is quite simply civil defense, based on science and the most recent technology; but in some countries this has been quickly grasped, while in others there has been a delay in comprehending it.”39 Le Wita rather admired the German way of doing things and wished it might be applied to France.40 Notwithstanding a small minority of authors such as Le Wita, however, there was consensus in France that removing parts of the population from urban centers would favour civil defense. As the military journalist Albert Paluel-Marmont put it, “Protecting the population means, first of all, evacuating it.”41 Within this consensus, French theorists differed with regard to the timing of such an evacua-

P A W E 21

tion (before, during, or after general mobilization), its practical aspects (the means of transportation to use, where to accommodate evacuees), and the population groups that should be included. They warned of the dangers of over-extended evacuations, but did not question the idea of evacuation itself.42 This feature of the French discourse distinguished it clearly from that of the Germans. “National character” explanations for divergent French and German views on evacuation stressed French individualism versus a German emphasis on the national community. But did German and French theorists actually have a different understanding of the individual’s role, especially in wartime? One way to address this question in the context of evacuations is to examine the role evacuation theorists assigned to families. The family comprised individuals held together by bonds of affection, loyalty, and interdependence; authors on both sides of the Rhine noted that evacuations threatened to rip it apart. Families existed “between” the individual and the state and could be interpreted as belonging to either sphere. Theorists’ choice of sphere is an indication of where they thought the emphasis should be placed and which was considered more important in wartime—the rights of the individual, or those of the state. In National Socialist evacuation theory, the family belonged to the state. Grimme and Giesler used arguments about family cohesion to support their stances against moving women and children out of cities. Their arguments appeared to favour the affective ties of individuals over the needs of the collective, but, in fact, the intention was quite different. Giesler contended that evacuations should be avoided because they ripped families apart, but then explained that families were the germ cell or nucleus of the state.43 Damaging them threatened the state as a whole. He and other Nazi theorists decried evacuations because it would be difficult and inefficient to set up special care for evacuated infants, the elderly, and the infirm, when such people were already being looked after quite efficiently at home. Instead, the family should continue doing what it had always done, looking after its members to leave the state free to pursue other (belligerent) endeavours. The family was also considered important in France. Here, however, its value to the individual was stressed, as was the individual’s power to make decisions about his or her family’s whereabouts. French writers recognized that evacuations would strain family cohesion, but did not see this as a reason to reject them entirely. Instead, they wanted individuals (particularly male heads of families) to be allowed as much latitude as possible in relocating their dependents, and they justified temporary discomfort through the larger goal of saving civilians’ lives. Albert Paluel-Marmont wrote in 1933 that, “The heads of families will send their family members, whose safety they will prefer to their presence, to smaller, less vulnerable communities.”44 His view accorded with that of the British, who also maintained that “any scheme for the evacuation of school children must be entirely voluntary in character, … the decision whether a child remains at home or

22 E C E G F, –

is evacuated with other school children must rest with its parents.”45 Throughout the 1930s, French theorists, like British theorists, emphasized the role of the individual in making decisions about whether or not to evacuate: “Each person can go where he wants, when he wants.”46 This attitude shaped measures during the war as well when French evacuation programs tried to take family ties and individual decision-making into account. During the occupation, French officials interceded with the Germans on behalf of the population to moderate the separations that German-ordered evacuations entailed. The French recognized the role of the paterfamilias in determining whether or not the family should be evacuated, fought for closer evacuations, and for permission to disperse people to the suburbs each night instead of sending them to more distant regions. In Germany, on the other hand, friction between the official view that the family was subsumed in the state, and the views of individuals, who felt that they should have control over family mobility, became a serious obstacle to successful evacuations. German theorists sometimes used arguments based on family unity to support their anti-evacuation stance, and German evacuations, when they came, made little allowance for family ties and freedom of choice. This meant that arguments based on family rights could be used to contest evacuation policies, an opposition that both threatened the war effort and undermined the legitimacy of the state. As the 1930s drew on, and war seemed more likely, the rift between French proponents of evacuation and their opponents across the Rhine grew more apparent. The French continued to favour evacuation over other defensive measures, while the German leadership reinforced pre-existing anti-evacuation views and progressively suppressed nearly all discussion of evacuation measures. Arguments in both countries continued to be linked to an imagined national character, with evacuation preferred by those who saw themselves as free individuals, while the propagandists of the Nazi Volksgemeinschaft pushed for a strong collective defense of the home community. Despite the force that “national character” arguments carried for contemporaries, they clearly cannot provide a complete explanation for the divergent viewpoints in the two countries. Perhaps it was the case that the French were more individualistic and liberal, and therefore more inclined toward voluntary evacuations. Certainly, in Germany, once the Nazis came to power, discipline and a commitment to fight to the death for the community were highly prized and discouraged discussion of evacuation. However, national character was above all a way to talk about evacuation, a way to argue either for or against it, and to explain why the two viewpoints had arisen in the first place. Ironically, men such as Grimme and Le Wita, who supported their evacuation theories with national character arguments, did so in a discursive context that was distinctly international. As time went on, observers in Germany and France paid

P A W E 23

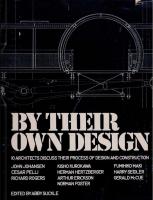

increasing attention to civil defense measures on the opposite bank of the Rhine. This was perfectly understandable, given the history of tension between the two countries. Douhet had theorized that the war of the future would begin with a decisive air strike, and who better to administer it than one’s nearest neighbour and perennial arch-rival? It made sense to keep a close eye not only on offensive capacities across the border, but also defensive ones, including air raid protection. Commentators in each country developed their ideas in the context of the other, using their neighbour’s policies to illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of their own. German propagandists never tired of pointing out that the crippling of Germany’s military through the Versailles Treaty had left the nation unfairly exposed to its enemies. Germany’s dense, highly urbanized population was vulnerable, and frightening images were produced to show that enemy planes could fly to the German heartland in as little as two hours (Figure 1.1).47 Publications such as Gasschutz und Luftschutz, Die Sirene, and Deutsche Justiz, a journal for jurists, followed international developments in air raid protection. They printed articles on Italy, Russia, the United States, and other countries, but in the later nineteenthirties, the bulk of their attention was focused on Britain, Holland, Belgium, and, most of all, France.

F 1.1. Germany Threatened by Enemy Aircraft Source: Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund Westfalen-Süd, Luftschutz tut Not! (Bochum: F. Kamp, n.d.), 3.

24 E C E G F, –