Women Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews [Paperback ed.] 0140117903, 9780140117905

This selection includes interviews with some of literature's great women: Dorothy Parker, Katherine Anne Porter, Li

867 207 8MB

English Pages 387 [397] Year 1989

Polecaj historie

![Women Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews [Paperback ed.]

0140117903, 9780140117905](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/women-writers-at-work-the-paris-review-interviews-paperbacknbsped-0140117903-9780140117905.jpg)

- Author / Uploaded

- George Plimpton

- Categories

- Literature

- Commentary

- The interviews in this collection are selected from Writers at Work, The Paris Review Interviews Series 1-8.

Table of contents :

- Introduction by Margaret Atwood

1. Isak Dinesen

2. Marianne Moore

3. Katherine Anne Porter

4. Rebecca West

5. Dorothy Parker

6. Lillian Hellman

7. Eudora Welty

8. Mary McCarthy

9. Elizabeth Hardwick

10. Nadine Gordimer

11. Anne Sexton

12. Cynthia Ozick

13. Joan Didion

14. Edna O'Brien

15. Joyce Carol Oates

- Notes on the Contributors

Citation preview

INTRODUCTION BY Ta ISAK DINESEN - MARIANNE MOORE ~ KATHERINE ANNE PORTER * REBECCA WEST ~ DOROTHY PARKER « LILLIAN HELLMAN EUDORA WELTY * MARYMcCARTHY : ELIZABETH HARDWICK * NADINE GORDIMER ANNE SEXTON « CYNTHIA OZICK ~ JOAN DIDION- EDNA O'BRIEN Ohter CABOLOATES

aa) BY GEORGE PLIMPTON

For more than thirty years, The Paris Review interviews have

been collected in the Writers at Work series. Here,at last, is a

specialized collection—interviews with fifteen women

novelists, poets, and playwrights,all Tae mareumxolilut-Ulielay

on the art of writing and on the unique problems and advan_ tages of being a woman writer in contemporary society. Praise for the Writers at Work series:

“For more than twenty-five years...the best confessional evidencebywriters about their work habits has been found in The melsKS WTA interviews.”

—LosAngeles Times Book Review

_ Continues to offer readers cas

ntive interviews

na erat nT eteeee “The Paris Review inte

ern literary interview.

ery model of the mod-

Wenerally the interviewees are well

chosen, the interviewers well prepared, the results well edited.... Taken together, they add. up to an intimate and engaging chronicle of contemporaryliterarylife.” —Time aenennne .

,

Se

eee eels Literary Criticism

U.K. CAN. USA

£6.99 $11.95 $8.95

ern Parts Ae Teen a

:

|

7

es

T

ISBN 0-14-011790-3 | |

9 "7801140°117

Manan onipiey

2079 Viewlynn Dr Vancouver BC V7J 2W7

PENGUIN BOOKS

WOMEN WRITERS AT WORK GEORGE PLIMPTONis perhaps best knownfor his widely read accounts of his experiences as an amateur playing sport at the professional level: Out of My League(baseball); Paper Lion (football); The Bogeyman (golf); Shadow Box (boxing); and Open Net (hockey). Editor of the literary quarterly The Paris Review, he has also co-edited a numberofbest-selling books: American Journey: The Times of Robert F. Kennedy, Edie: An American Biography; and D.V.. His most recent book is The Curious Case of Sidd Finch, a novel. MaArGarET ATWOODis the authorof over twenty volumesof poetry, fiction, and non-fiction. She has received many accolades for the body of her work and individual awards for her six novels, The Edible Woman, Surfacing,

Lady Oracle, Life Before Man, Bodily Harm, and The Handmaid’s Tale,

which was short-listed for the prestigious Booker Prize. A seventh novel, Cat’s Eye, was published to great acclaim in 1989. | In addition to her literary accomplishments, Ms. Atwood has served as President of International P.E.N. (Canadian-Anglophone chapter), and been awarded honorary degrees from several universities. In 1987, she received the Humanist of the Year award. Ms. Atwood was born in Ottawa and grew upin northern Ontario, Que-

bec, and Toronto. She hastravelled widely and lived in England, Germany, France, Italy, and the United States. She now lives in Toronto with novelist

Graeme Gibson andtheir daughterJess.

The Paris Review was founded in 1953 by a group of young Americans including Peter Matthiessen, Harold L. Humes, George Plimpton, Thomas Guinzburg, and Donald Hall. While the emphasis of its editors was on publishing creative work rather than nonfiction (among writers who published their first short stories there were Philip Roth, Terry Southern, Evan S. Connell, and Samuel Beckett), part of the magazine’s success can be attributed to its continuing series of interviews on the craft of writing.

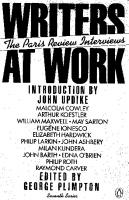

Previously Published

WRITERS AT WORK

The Paris Review Interviews

FIRST SERIES

Edited and introduced by MALCOLM COWLEY E. M. Forster Francois Mauriac Joyce Cary Dorothy Parker James Thurber Thornton Wilder William Faulkner Georges Simenon

Frank O’Connor Robert Penn Warren Alberto Moravia Nelson Algren

Angus Wilson

William Styron Truman Capote Francoise Sagan

SECOND SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTONand introduced by

VAN WYCK BROOKS

Robert Frost Ezra Pound

Marianne Moore

T. S. Eliot Boris Pasternak Katherine Anne Porter Henry Miller

Aldous Huxley

Ernest Hemingway S. J. Perelman Lawrence Durrell

Mary McCarthy —

Ralph Ellison Robert Lowell

THIRD SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTON and introduced by ALFRED KAZIN William Carlos Williams Blaise Cendrars

Jean Cocteau Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Evelyn Waugh

Lillian Hellman

William Burroughs

Saul Bellow Arthur Miller James Jones Norman Mailer

Allen Ginsberg

Edward Albee Harold Pinter ©

FOURTH SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTON and introduced by WILFRID SHEED Isak Dinesen Conrad Aiken Robert Graves George Seferis John Steinbeck Christopher Isherwood W. H. Auden Eudora Welty

John DosPassos Vladimir Nabokov Jorge Luis Borges John Berryman Anthony Burgess Jack Kerouac Anne Sexton

John Updike

FIFTH SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTONand introduced by

FRANCINE DU PLESSIX GRAY

Joyce Carol Oates Archibald MacLeish Isaac Bashevis Singer John Cheever Kingsley Amis William Gass Joseph Heller Jerzy Kosinski Gore Vidal Joan Didion

P. G. Wodehouse Pablo Neruda Henry Green Irwin Shaw James Dickey

SIXTH SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTONandintroduced by

FRANK KERMODE

Rebecca West

Stephen Spender Tennessee Williams Elizabeth Bishop Bernard Malamud William Goyen

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Nadine Gordimer James Merrill Gabriel Garcia Marquez Carlos Fuentes John Gardner

SEVENTH SERIES

E:dited by GEORGE PLIMPTON andintroduced by JOHN UPDIKE Malcolm Cowley William Maxwell

Arthur Koestler

MaySarton Eugene Ionesco Elizabeth Hardwick John Ashbery Milan Kundera John Barth Edna O’Brien Philip Roth Raymond Carver

Philip Larkin

EIGHTH SERIES

Edited by GEORGE PLIMPTON andintroduced by

JOYCE CAROL OATES

E. B. White Elie Wiesel Leon Edel Derek Walcott Robert Fitzgerald E.. L. Doctorow John Hersey Anita Brookner James Laughlin Robert Stone Cynthia Ozick Joseph Brodsky John Irving

Women Writers at Work The Paris Review Interviews Edited by George Plimpton

Introduction by Margaret Atwood

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 s5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England First published in simultaneous hardcover and paperback editions by Viking Penguin Inc., 1989 Published simultaneously in Canada 13579108642 Copyright © The Paris Review, Inc., 1989 All rights reserved The interviews in this collection are selected from Writers at Work, Series 1-8, published by Viking Penguin Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Womenwriters at work: the Paris review interviews / edited by George Plimpton ; introduction by Margaret Atwood. p. cm. ISBN 0 14 01.1790 3 1. Women authors—zoth century—Interviews. 2. Literature, Modern—zoth century—History andcriticism. 3. Literature, Modern— Womenauthors—History andcriticism. 4. Authorship. I. Plimpton, George. II. Paris review. PN471.W56 1989b 809’.89287—dc19 88-37078 Printed in the United States of America Set in Electra

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition thatit

shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, te-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated

without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents Introduction by Margaret Atwood 1. 2. 3.

ISAK DINESEN

1

MARIANNE MOORE

19

KATHERINE ANNE PORTER 4.

REBECCA WEST

45

71

5.

DOROTHY PARKER

107

6.

LILLIAN HELLMAN

121

7.

EUDORA WELTY

147

8.

MARY MCCARTHY

169

9.

ELIZABETH HARDWICK

10.

NADINE GORDIMER

11. 12.

15.

201 225

ANNE SEXTON

263

CYNTHIA OZICK

201

13.

JOAN DIDION

319

14.

EDNA O'BRIEN

337

JOYCE CAROL OATES

NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS 1X

361 385

xi

Introduction

his new volumeof the Paris Review's highly praised and praiseworthyseries of interviews with writers is a departure from the norm. Previous collections have mixed the genders; this oneis unisexual. That the editors have chosen to bring together, within the samecovers, fifteen writers as diverse as Dorothy Parker and Nadine Gordimer, Marianne Moore and Rebecca West, Isak Dinesen and Lillian Hellman, Mary McCarthy and Katherine AnnePorter, over what, in some cases, would doubtless be their dead bodies, merely because they share a double-X chromosome, is not due to a sudden mental aberration. Rather it has been the result of readers’ requests. Whynot a gathering of womenwriters? the editors were asked. Well, why not? Which is not quite the same thing as why. To some the answer would seem self-evident: women writers belong together because they are different from men, and the writing they do is different as well and cannot be read with the same eyeglasses as those used for the reading of male writers. Nor can writing by womenberead in the same way by men asit can by women, and vice versa. For many women, Heathcliff is a romantic hero; for many men, heis a posturing oaf they’d like to punchin the nose. For many men, The Ginger Man’s Sebastian Dangerheld is an energy-packed rebel; for many women, heis an immature and tiresome wife-beater. Paradise Lost reads difx1

X11

Introduction

ferently when viewed by the daughters of Eve, and with Milton’s browbeaten secretarial daughters in mind; and so on down through the canon. Such gender-polarized analyses can reach beyond subjectmatter and point of view to encompass matters of structure and style: are women really more subjective? do their novels really

end with questions? Especially in this age of semiotics, genderlinked analysis may seek to explore attitudes towards language

itself. Is there a distinct female écriture? Does the mother-tongue

really belong to mothers, or is it yet one more male-shaped institution bent, like foot-binding, on the deformation and hobbling of women? I have had it suggested to me, in all seriousness, that

women ought not to write at all, since to do so is to dip one’s hand, like Shakespeare’s dyer, into a medium both sullied and

sullying. (This suggestion was not made telepathically, but in

spoken sentences; since, for polemicists as for writers themselves, the alternative to languageis silence. ) I was recently on a panel—that polygonal form of discourse so beloved of the democratic twentieth century—consisting entirely of women, including Jan Morris, who used to be James Morris, and Nayantara Sahgal of India. From the audience came the question, “How do you feel about being on a panel of women?” Weall prevaricated. Some of us protested that we had been on lots of panels that included men; others said that most panels were male, with a woman dotted here and there for decorative effect, like parsley. Jan Morris said that she was in the process of transcending gender and was aiming at becoming a horse, to which Nayantara Sahgalreplied that she hoped it was an English horse, since in some other, poorer countries, horses were not treated very well. Which underlined, for all of us, that there are categories other than male and female worth considering. I suppose weall should have said, “Why not?” Still, I was. intrigued by our collective uneasiness. No woman writer wants to be overlooked and undervalued for being a woman; butfew, it seems, wish to be defined solely by gender, or constrained by loyalties to it alone—anattitude which may puzzle, hurt or enrage those whose political priorities cause them to view writing as a

Introduction

X11

tool, a means towards an end, rather than as a Muse whowill desert you if you break trust. In the interview which beginsthis collection, Dorothy Parker articulates the dilemma: I’m a feminist, and God knows I’m loyal to my sex, and you must rememberthat from my very early days, when this city was scarcely safe from buffaloes, I wasin thestruggle

for equal rights for women. But when weparaded through

the catcalls of men and when wechained ourselves to lamp posts to try to get our equality—dearchild, we didn’t foresee those female writers. (Pp. 114-115) Male writers may suffer strains on their single-minded dedication to their art for reasons ofclass or race or nationality, but so far no male writeris likely to be asked to sit on a panel addressing itself to the special problems of the male writer, or be expected to support anotherwriter simply because he happensto be a man. Such things are asked of women writers all the time, and it makes them jumpy. Virginia Woolf may have been right about the androgynous

nature ofthe artist, but she was right also about the differences

in social situation these androgynousartists are certain to encounter. We mayagree with Nadine Gordimer whenshesays, “By and large, I don’t think it matters a damn whatsex a writer is, so long as the work is that of a real writer” (p. 260), if what she meansis that it shouldn’t matter, in any true assessment of talent or accomplishment; but unfortunately it often has mattered, to other people. When Joyce Carol Oates is asked the “woman” question, phrasedin hercase as““Whatare the advantagesofbeing a woman writer?”, she makes a virtue of necessity: Advantages! Too many to enumerate, probably. Since, being a woman, I can’t be takenaltogether seriously by the sort of male critics who rank writers 1, 2, 3 in the public press, I am free, I suppose, to do as I like. (P. 382)

xiv

Introduction

Joan Didionis asked the same question in its negative form—

“disadvantages” instead of “advantages”—andalso focuses on so-

cial differences, social acceptance androle:

WhenI wasstarting to write—in the late fifties, early sixties—there was a kind ofsocial tradition in which male novelists could operate. Hard drinkers, bad livers. Wives, wars, big fish, Africa, Paris, no second acts. A man who wrote novels had a role in the world, and he could play that role and do whatever he wanted behind it. A woman

who wrote novels had no particular role. Women whowrote

novels were quite often perceived as invalids. Carson McCullers, Jane Bowles. Flannery O’Connor of course. Novels by women tended to be described, even by their publishers, as sensitive. I’m notsure this is so true anymore, but it certainly was at the time, and I didn’t muchlikeit. I dealt with it the same way I deal with everything. I just tended my own garden, didn’t pay much attention, behaved—I suppose—deviously. (Pp. 324-325) I think of Marianne Moore, living decorously with her mother

and her “dark” furniture, her height of social rebellion the cou-

rageous ignoring of the need for chaperones at Village literary parties, and wonder how many male writers could have lived such

a circumscribed life and survived the image.

Not least among perceived social differences is the difficulty women writers have experienced in being taken “altogether seriously”as legitimate artists. Ezra Pound, writing in the second decade of this century, spoke for many male authors andcritics before and since: “I distrust the ‘female artist.’ . . . Not wildly anti-feminist we are yet to be convinced that any woman ever invented anythingin the arts.” (Carpenter, A Serious Character,

Houghton Mifflin, 1988, p. 239.) Cognate with this view of

writing as a malepreserve has been the image of womenwriters as lightweight puffballs, neurotic freaks suffering from what Edna O’Brien calls “a double dose of masochism: the masochism of the womanandthatofthe artist” (p. 342), or, if approved of, as

Introduction

xv

honorary men. Femininity and excellence, it seemed, were mutually exclusive. Thus Katherine Anne Porter: If there is such a thing as a man’s mind and a woman’s mind—andI’m sure there is—it isn’t what most critics mean whenthey talk about the two. If I show wisdom, they say I have a masculine mind. If I am silly and irrelevant—and Edmund Wilsonsays I often am—whythentheysay I have a typically feminine mind! . . . But I haven’t ever found it unnatural to be a woman. (P. 65)

The interviewer responds with a question that is asked, in one

form or another, not only of almost every woman included in this book, but of almost every woman writer ever interviewed: “But haven’t you found that being a woman presented to you, as an artist, certain special problems?” Katherine Anne Porter’s reply—‘“I think that’s very true and very right”—is by no meansthe only onepossible. Some, such as Mary McCarthy,are clearly impatient with the questionitself. McCarthy accepts some version of the “masculine” versus the “feminine”sensibility, but aligns herself firmly with the former. INTERVIEWER: What do you think of women writers, or do you think the category “woman writer” should not be made? MCCARTHY: Some womenwriters makeit. I mean, there’s a certain kind of woman writer who’s a capital W, capital W.Virginia Woolf certainly was one, and Katherine Mansheld was one, and Elizabeth Bowenis one. Katherine Anne

Porter? Don’t think she really is—I mean, her writing is

certainly very feminine, but I would say that there wasn’t this “WW”business in Katherine Anne Porter. Whoelse? There’s Eudora Welty, who’s certainly not a “Woman Writer,” though she’s becomeonelately. INTERVIEWER: What is it that happens to make this change? MCCARTHY: I| think they becomeinterested in décor. You

XVI

Introduction

notice the change in Elizabeth Bowen. Herearly work is

much more masculine. Her later work has much more drapery in it. . . . I was going to write a piece at some point aboutthis called “Sense and Sensibility,” dividing women writers into these two. I am for the ones who represent sense .. . (Pp. 189—190) Cynthia Ozick goes muchfarther; she refuses such dichotomies altogether: INTERVIEWER: . . . you have written about the writer as

being genderless and living in the world of “as if” rather than being restrained by her...

OZICK: Parochial temporary commitments. . . . A writer is someone born with a gift. An athlete can run. A painter can paint. A writer has facility with words. A good writer can also think. Isn’t that enough to define a writer by?

(P. 304)

Cynthia Ozick also says that the biographers of Wharton and Woolf “missed the writer” in their subjects, and this is probably easier to do with women than with men. Thereis, still, a sort of

trained-dog fascination with the idea of women writers—not that the thing is done well, but that it is done at all, bya creature that is not supposed to possess such capabilities. And so a biographer may well focus on the woman, on gossip and sexualdetail

and domestic arrangements andpolitical involvement, to the ex-

clusion of the artist. But it is impossible to read any ofthe interviews in this book and “miss the writer.” What these writers have in common is not their diverse responses to the category “woman writer,” but their shared passion towards the category “writer.”

Reading throughthese interviews, I was struck again and again

by the intensity of this passion: the commitmentto craft, the informed admiration for the work of other writers from whom they have learned, the insistence on the importance, not of what they themselves have done, but on what has been and can be

Introduction

XVi1

done through the art itself. In no other art, except painting, perhaps, is the relationship of creation to creator so complex and personal and thusso potentially damagingto self-esteem: if you fail, you fail alone. The dancer realizes someoneelse’s dance, the writer her own. The relationship of any writer towards a

vocation so exacting in its specificity, so demanding of love and

energy and time, soresistantto all efforts to define its essence or to categorize its best effects, is bound to be an edgy one, and in these conversations the edginess shows through. Somedisclaim ego, remarkable in a collection of such strong, assertive, individual voices; others keep secrets; others fence with their considerable intelligence; others protect themselves with wit. Some recommend objectivity, McCarthy’s “sense”; others, like Edna O’Brien,

speak of necessary demons. It would be a brave person who would

try to stuff these wonderful and various talents into one tidy box labelled “WW,”and expect that acronym to be definitive. Despite thetitle of this book, the label should probably read, “WWAAW,” Writers Who Are Also Women. This is not the only collection of such writers that could be

made. It is limited in scope by the writers actually interviewed

to date by The Paris Review. Thus, although there are writers from the United States, Ireland, England, Denmark, and South Africa, there are none here from, for instance, India or Australia or Canada or Latin America: no Alice Munro, no Anita Desai, no Isabel Allende. As this assemblage is unisexual, so is it unicolored: thus far no Toni Morrison, no Alice Walker, no Louise Erdrich. Nor are there manywriters who are knownfor an explicit and self-aware examination of the more colonial features of the relationships between men as a group and women: no Marilyn French, no Marge Piercey, no Fay Weldon, no AdrienneRich, no Judith Rossner. Some of these omissions may be set down to the slowness characteristic of the mills of the gods and the editors of small magazines, a slowness which may account, too, for the

retrospective slant of this volume. But looking back over the

territory to see what has been done and, especially, said before, is, in the case of writing, part of theterritory.

xvill

Introduction

To write is a solitary and singular act; to do it superbly, as all

of these writers have done, is a blessing. Despite everything that gets said about the suffering and panic and horror of being a

writer, the final impression left by these remarkable voices is one of thankfulness, of humility in the face of what has been given. From Joyce Carol Oates, one of the youngest writers inthis group: I take seriously Flaubert’s statement that we must love one anotherin ourart as the mystics love one another in God. By honoring one another’s creation we honor some-

thing that deeply connects us all, and goes beyond us.

(Pp. 383-384)

And from Dorothy Parker, one of the oldest: I want so much to write well, though I know I don’t. .

But during andat the end of mylife, I will adore those who

have. (P. 119)

:

MARGARET ATWOOD, 1988

WOMEN WRITERS AT WORK

1. Isak Dinesen

Isak Dinesen was born Karen Dinesen in 1885 in Rungstedlund, Denmark, and spentherearly years in the fashionable world of Copenhagen’s upperclass. In 1913 she became engaged to her Swedish cousin, Baron Bror von Blixen-Finecke, and they decided to emigrate to Africa and buy a farm. They were married

in 1914 in Mombasa and moved onto large plantation near

Nairobi. The marriage was an unhappyone; they were separated after only a few years and divorced in 1921. Karen Blixen continuedto live on the coffee plantation, which she developed and

ran for seventeen years. When the coffee market collapsed in

1931, she was forced to leave Africa and return to her family

home in Rungstedlund. There she dedicated herself to writing

under the nameof Isak Dinesen. Seven Gothic Tales was published in England and America in 1934 andestablished her reputation. Out ofAfrica, a novel about her years in Kenya, was published in 1937. Herlater works include Winter's Tales (1942), Last Tales (1957), Anecdotes of Destiny (1958), Shadows on the Grass (1960), and Ehrengard (1963). Isak Dinesen continuedto live in Denmark forthe rest of her life. Herill health in those years has beenattributed to a venereal disease, caught from her husband duringthe first year of their marriage, which was never properly treated. She spent long periods of time in the hospital, often too ill and weak to sit upright, dictating her later stories to her secretary. She died at the age of seventy-seven on September 7, 1962. 1

ar 2 Lacan 0 Z CIF4 (>< one >x“

en Ad

IDba

![Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, Eighth Series [Paperback ed.]

0140107614, 9780140107616](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/writers-at-work-the-paris-review-interviews-eighth-series-paperbacknbsped-0140107614-9780140107616.jpg)