Marcel Duchamp

523 128 91MB

English Pages [88]

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

MARCEL DUCHAMP

There is no solution because there is no problem. Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp: Jeune homme et jeune fille dans le printemps, 1911 (Israel Museum, Jerusalem).

1887

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp is born on 28 July in BlainvilleCrevon (then Seine-Inférieure), a Norman village some 20 kilometers northeast of Rouen. He is the fourth child of Justin-Isidore “Eugène” Duchamp and Marie-CarolineLucie Nicolle. Born in 1848 in Massiac (Cantal) to café owners, Eugène began his career as a clerk in a municipal tax office. He was transferred to Damville (Eure) in 1874. Later that same year, he met and married Lucie, who was born in Rouen in 1856. Her father, ÉmileFrédéric Nicolle, was a notary clerk turned local shipping agent who had retired in 1875 to devote himself to painting and engraving. Lucie, too, had a penchant for drawing and painting. The couple’s first two children were born in Damville: Émile-Méry-Frédéric-Gaston in 1875 and Pierre-Maurice-Raymond the following year. In 1876, the family moved to Cany-Barville on the Normandy coast. Jeanne-MarieMadeleine was born there in 1883, a few months before the Duchamps settled in Blainville-Crevon. The recent death of the village notaire inspired Eugène to purchase the vacant practice. Nearly seven months before Marcel’s birth (on

Marcel Duchamp, circa 1890 (Archives Jean-Jacques Lebel).

29 December 1886), Madeleine died of croup. In Blainville-Crevon, Lucie gave birth to three more children: Suzanne-Marie-Germaine in 1889, Marie-Madeleine-Yvonne in 1895, and Marie-Thérèse-Magdeleine in 1898.

CHRISTMAS 1895

Gaston announces to his parents that he is dropping out of law school to become an artist. He soon adopts the name Jacques Villon.

1897

Like his brothers, Duchamp enrolls at the Lycée Corneille in Rouen. Boarding at the nearby École Bossuet, he meets Ferdinand Tribout and Raymond Dumouchel, who remain lifelong friends. He takes drawing lessons at the lycée from Philippe Zacharie, a teacher at Rouen’s École des Beaux-Arts.

Marcel and Suzanne Duchamp, Blainville-Crevon, circa 1895–1900 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Marcel Duchamp: L’Église de Blainville, 1902 (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

(Left to right) Suzanne Duchamp, Lucie Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp, Clémence Lebourg (the Duchamps’ servant), and Yvonne Duchamp, Blainville-Crevon, 1895 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1900

Raymond quits medical school and takes up sculpture, assuming the pseudonym Raymond DuchampVillon.

1902

Duchamp undertakes his first serious attempts at art. He produces several drawings, many of which take Suzanne as their subject, and his first oil paintings, all of which focus on the area around the family home and the neighboring church. In autumn, he carefully draws a bec Auer gas lamp hanging at the École Bossuet, a theme that will resurface in his oeuvre.

1904

Graduating from the Lycée Corneille, Duchamp is awarded the medal of excellence for drawing from the Société des amis des arts. His parents allow him to join his brothers in Paris. Living with Villon at 71 rue Caulaincourt in Montmartre, he enrolls at the Académie Julian in November.

Gaston Duchamp, known as “Jacques Villon,” his father, Eugène Duchamp, and his brother, Raymond Duchamp, known as “Raymond Duchamp-Villon,” circa 1900 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Marcel Duchamp: Bec Auer, circa 1902 (Private collection).

Make a painting of happy or unhappy chance (luck or unluck).

1905–1906

Duchamp fails the entrance exam for the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. To avoid two years of military service, he decides to become an ouvrier d’art (art craftsman). He returns to Rouen and apprentices at the Imprimerie de la Vicomté, mastering the techniques of etching, engraving, and typesetting. He lives with his parents, who recently have moved to 71 rue Jeanne d’Arc, following the retirement of Duchamp père. In October, he voluntarily serves in the 39th Infantry Regiment of the French army. Discharged a year later with the rank of corporal, he returns to Montmartre and rents an apartment at 65 rue Caulaincourt. His brothers have moved into neighboring studios at 7 rue Lemaître in Puteaux, then a quiet suburb of Paris. Duchamp resumes drawing, and frequents Gustave Candel and Juan Gris.

1907

Like other celebrated satirists in Montmartre, Duchamp creates humoristic and often sexually suggestive drawings. He exhibits five of them publicly for the first

Jacques Villon: Portrait de Marcel Duchamp, 1904 (Private collection).

Marcel Duchamp: Nu sur un escabeau, 1907–1908 (Private collection).

time at the inaugural Salon des artistes humoristes in Paris. He recommences painting.

1908

Following Villon’s example, Duchamp begins to sell his humoristic drawings to Le Courrier français and Le Rire for publication. He also exhibits at the Salon d’automne. Moving to 9 rue de l’Amiral-de-Joinville in Neuilly-sur-Seine, he visits his brothers regularly in Puteaux.

1910

Duchamp begins a liaison with Jeanne Serre. Estranged from her husband, she works as an artist’s model. He also meets the German-born art student Max Bergmann, visiting Paris from Munich. Duchamp paints several portraits of family and friends, all indebted to Cézanne. The most ambitious is La Partie d’échecs, a group likeness of his brothers at a chessboard with their spouses nearby. Villon taught Duchamp to play chess, and it will become a lifelong passion.

Marcel Duchamp: Facsimile of a drawing for the Large Glass, 1914.

Marcel Duchamp: Nuit blanche and Vice sans fin, two humoristic drawings published in Le Courrier français in November 1909 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1911

Jeanne Serre gives birth to Duchamp’s daughter, YvonneMarguerite-Marthe-Jeanne, known as Yo, on 6 February. Like her father, she eventually will take up painting. Duchamp adopts a cubist style, partly indebted to Villon. Aware of the chronophotography of Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, he also experiments with depicting multiple images of a single body in motion in paintings like Portrait (Dulcinée), Jeune homme triste dans un train (a selfportrait), and the initial version of Nu descendant un escalier. He produces a series of drawings and paintings of two chess players (his brothers), painting the final canvas at night by gaslight. DuchampVillon requests various friends to contribute paintings to decorate his kitchen in Puteaux. Duchamp executes Moulin à café, his first attempt at machine imagery. He is increasingly interested in the fourth dimension, as well as avantgarde literature and poetry, such as the work of Mallarmé, Raymond Roussel, and Jules Laforgue. He meets Francis Picabia.

Marcel Duchamp: Moulin à café, 1911 (Tate Modern, Londres).

1912

In January, Duchamp completes the second version of Nu descendant un escalier. When he submits it to the Salon des indépendants, the mechanomorphic figure shocks Gleizes and Metzinger. His brothers inform him that the work has been rejected. The canvas subsequently is featured in a cubist exhibition at the Galeries J. Dalmau in Barcelona. With Apollinaire and Picabia, he attends a performance of Roussel’s Impressions d’Afrique. In late June, he travels to Munich for two months. He produces two important paintings (Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée and the Mariée) and four drawings, among them the first study for his magnum opus, La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même, commonly know as the Large Glass. He also begins jotting notes and making sketches on bits of scrap paper, exploring the components and complex functioning of the Large Glass. In October, accompanied by Apollinaire, Picabia, and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, he takes a trip into the Jura Mountains near the Swiss border. The Nu is shown in Paris at the Salon de la Section d’Or.

(Previous page) Marcel Duchamp: Jeune homme triste dans un train, 1911 (Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venise).

Marcel Duchamp: Nu descendant un escalier (nos. 1 et 2), 1911 and 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

1913

In Les Peintres cubistes, Apollinaire proclaims: “Perhaps it will be the task of an artist as detached from aesthetic preoccupations, as preoccupied with energy as Marcel Duchamp, to reconcile Art and the People.” Nu descendant un escalier (no. 2) is a succès de scandale at New York’s International Exhibition of Modern Art (a.k.a. the Armory Show). Derided by one journalist as an “explosion in a shingle factory,” the canvas is bought by a San Francisco collector sight unseen. Duchamp embraces “canned chance” as a creative impetus, “composing” Erratum musical and beginning 3 Stoppages étalon. He executes additional preparatory works for the Large Glass, all of which are mechanical in style, including his first work on glass. Moving back to Paris, he takes a job at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. He mounts a bicycle wheel upside down on a stool, the first object he would later dub a “readymade.”

Marcel Duchamp: Drawing for the stationmaster for 9 Moules mâlic, 1913–1914 (Private Collection).

Marcel Duchamp: Roue de bicyclette, 1964, replica of the 1913 original (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

1914

Duchamp continues to fashion major studies for the Large Glass, among them Broyeuse de chocolat (no. 2) and 9 Moules mâlic. Chosen on the basis of visual indifference and intended as an interrogation of “retinal” art, he buys a bottle rack and a commercial print of a landscape as readymades. In an edition of five, he produces the Boîte de 1914, comprised of facsimiles of a drawing and 16 manuscript notes. With the outbreak of World War I, Villon and Duchamp-Villon are drafted.

1915

Suffering from a heart murmur, Duchamp is declared unfit for military service. He accepts Walter Pach’s invitation to move to New York, landing in Manhattan on 15 June. Pach soon introduces him to Walter and Louise Arensberg, who will become close friends and his main patrons. After living with the Arensbergs, Duchamp takes a studio at 1947 Broadway and commences the Large Glass. He buys and inscribes a snow shovel, coins the term “readymade,” and

(Preceding double page) Percy Rainford: Installation of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the Armory Show, 69th Regiment Armory, New York, 17 February–15 March 1913 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC).

Henri-Pierre Roché: Three views of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades in his New York studio, 33 West 67th Street, circa 1916–1918 (Archives Jean-Jacques Lebel).

confesses years later: “I’m not at all sure that the concept of the readymade isn’t the most important single idea to come out of my work.” Duchamp meets Man Ray.

1916

Frequenting lively soirées at the Arensbergs’ apartment, Duchamp befriends Henri-Pierre Roché, Beatrice Wood, Joseph Stella, Charles Demuth, Edgard Varèse, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Fania and Carl Van Vechten, Arthur Cravan, Mina Loy, and others. He continues his investigation of the readymade, producing Comb, À bruit secret (with Walter Arensberg), and ...pliant,...de voyage. The Bourgeois Gallery publicly exhibits two unidentified readymades for the first time. Duchamp moves into a studio in the Arensbergs’ apartment building at 33 West 67th Street. They pay his rent in exchange for ownership of the Large Glass. As founding members of the Society of Independent Artists, he and Katherine Dreier become acquainted. He recreates Roue de bicyclette in his New York studio.

The litanies of the chariot: Slow life. Vicious circle. Onanism. Horizontal. Round trip for the buffer. Junk of life. Cheap construction. Tin, cords, iron wire. Eccentric wooden pulleys. Monotonous fly wheel. Beer professor. (to be entirely redone).

Marcel Duchamp: Apolinère Enameled, 1916–1917 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), and ...pliant,...de voyage, 1964, replica of 1916 original.

The bachelor grinds his chocolate himself.

1917

Under the pseudonym “R. Mutt,” Duchamp submits a urinal entitled Fountain to the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. The directors vote to reject this readymade, despite their edict “no jury, no prizes.” Duchamp resigns from the board in protest. Alfred Stieglitz photographs Fountain, which is lost or destroyed soon thereafter. With Wood and Roché, Duchamp publishes two issues of The Blind Man. The second issue contains an editorial defending Fountain: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He chose it.” He is increasingly friendly with the wealthy Stettheimer sisters (Carrie, Ettie, and Florine).

1918–1919

Katherine Dreier commissions Duchamp to paint a canvas for her apartment, after which he renounces painting altogether. Dominated by cast shadows of several previous works, Tu m’ is “a form of résumé,” according to Duchamp. He has a cameo in Léonce Perret’s film Lafayette! We Come! After the United States

Alfred Stieglitz: Photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade entitled Fountain, 1917 (Private collection).

Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, and Henri-Pierre Roché: The Blind Man, no. 2, May 1917 (Collection Francis M. Naumann).

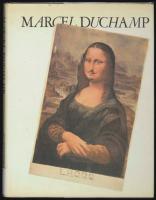

enters the war, Duchamp and his companion, Yvonne Chastel, leave New York in August for Buenos Aires. Dreier follows them. In the Argentine capital, he executes a study in glass for the Large Glass, attempts to organize a cubist exhibition, and designs both rubber stamps for playing correspondence chess and a wooden chess set. Duchamp-Villon dies on 7 October 1918. As a wedding gift to Suzanne and her new husband, Jean Crotti, he instructs them to create Ready-made malheureux. After ten months of avid chess playing, he confesses to Walter Arensberg: “I feel I am quite ready to become a chess maniac.” Returning to Europe in August 1919, Duchamp lives with Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia. He purchases a chromolithograph of the Mona Lisa, adds a mustache and goatee to the face, and inscribes L.H.O.O.Q. beneath her. This risqué “rectified” readymade becomes a talisman for the Dada movement.

Katherine Dreier or Yvonne Chastel (?): Marcel Duchamp in front of a chessboard in Buenos Aires, January 1919 (Archives Jean-Jacques Lebel).

Marcel Duchamp: L.H.O.O.Q., 1919 (Private collection).

1920

Marcel Duchamp: 50 cc air de Paris, 1919 (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

Landing in New York in January, Duchamp brings 50 cc air de Paris as a present for the Arensbergs, who already have assembled a sizable collection of his work. With Katherine Dreier and Man Ray, Duchamp founds the Société Anonyme, Inc., the first museum of modern art in the United States. He initially serves as its president and exhibition chairman and later as its secretary. In his studio at 246 West 73rd Street, he fabricates Rotative plaques verre (optique de précision), his first motorized optical machine. After Duchamp relocates his studio to 1947 Broadway, Man Ray photographs the accumulation of dust on the Large Glass. Duchamp’s drag persona, Rose Sélavy, is “born” and lends her signature to puns and readymades, the first being Fresh Widow.

1921

Man Ray photographs Duchamp in drag as Rose Sélavy. They publish New York Dada, the cover of which depicts the readymade Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette. With various readymade elements,

Establish a society in which the individual has to pay for the air he breathes (air meters); imprisonment and rarefied air, penality in case of non-payment, simple asphyxiation if necessary (cut off the air).

Man Ray: Marcel Duchamp cross-dressed as Rrose Sélavy, 1920–1921 (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

Duchamp fabricates Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? The Arensbergs move to California. Invited by Tristan Tzara to participate in a group Dada exhibition in Paris, Duchamp refuses, replying from New York “pode bal” (balls to you). He returns to Paris in June, and Picabia introduces him to the Parisian Dadaists, including Tzara, André Breton, Louis Aragon, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Philippe Soupault. Duchamp amends Rose Sélavy to Rrose Sélavy, a pun on éros, c’est la vie.

1922

Duchamp returns to New York and continues work on the Large Glass. Breton publishes the first significant critical text on Duchamp in the October issue of Littérature. In the December issue of the same journal, Breton includes puns and spoonerisms that Robert Desnos claims to have received telepathically while in a trance from Rrose Sélavy.

Man Ray: Robert Desnos in a trance receiving the puns and spoonerisms of Rrose Sélavy via telepathy, 1922 (Man Ray Trust).

1923–1924

The Arensbergs sell the Large Glass to Katherine Dreier. Duchamp ceases work on his magnum opus, declaring it “definitely unfinished.” In February, he moves to Brussels and plays chess professionally. Resettling in Paris, he spends his time studying chess problems, and renews his friendship with Brancusi, whom he had met around 1912. In late 1923 or early 1924, he initiates a liaison with Mary Reynolds. Jacques Doucet commissions a second optical machine, on which Duchamp works for most of 1924. He travels around France, competing in chess tournaments. In Monte Carlo, he devises a system of betting in roulette based on chance, and issues 30 bonds to finance the operation. Duchamp Man Ray: Marcel Duchamp and and Man Ray are seen playing chess Brogna Perlmutter in Ciné-sketch, in René Clair’s and Picabia’s film Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, Entr’acte. On 31 December 1924 31 December 1924 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées as part of Ciné-sketch, Duchamp appears on stage nude as Adam in a tableau vivant after a work by Man Ray: Mary Reynolds, Paris, Cranach. circa 1925 (Archives Laurence Vail).

(Preceding double page) Marcel Duchamp: Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, 1921 (Private collection).

1925–1926

Duchamp’s mother dies on 29 January. His father follows five days later. He participates in the French chess championship in Nice, for which he designs the poster. Using his inheritance, Duchamp makes Anémic Cinéma, a short film composed of puns by Rrose Sélavy arranged on rotating disks and interspersed with abstract optical spirals. He purchases 80 artworks by Picabia and puts them up for auction at Hôtel Drouot in Paris. He and Dreier organize the International Exhibition of Modern Art sponsored by the Société Anonyme at the Brooklyn Museum, where the Large Glass is shown publicly for the first time. In fall 1926, Duchamp returns to New York to install an exhibition Marcel Duchamp’s parents, circa 1923–1924 (Archives Marcel of Brancusi’s work at the Brummer Duchamp). Gallery. He meets Julien Levy.

1927

In New York, Duchamp, Roché, and Mary Rumsey purchase numerous Brancusi sculptures sold as part of John Quinn’s estate. He travels to Chicago to install a Brancusi exhibition at the Arts Club of Chicago. Returning to Paris in

Marcel Duchamp: Obligation pour la Roulette de Monte-Carlo, 1924 (current whereabouts unknown).

(Preceding double page, second row, second from left) Marcel Duchamp at the French chess championship organized by the Fédération française des échecs, Strasbourg, 31 August 1924.

late February, he rents a studio at 11 rue Larrey. With Man Ray and Antoine Pevsner, he remodels the apartment, installing a single door that serves two doorways. The Picabias introduce Duchamp to Lydie Sarazin-Levassor. They marry on 7 June.

1928–1929

On 25 January, Duchamp and Sarazin-Levassor are officially divorced, and he renews his relationship with Mary Reynolds. Continuing to play competitive chess, he admits to Katherine Dreier: “Chess is my drug.” In spring 1929, he and Dreier spend several weeks in Spain.

1930–1931

Duchamp creates a second version of L.H.O.O.Q., which is featured in a Parisian exhibition organized by Aragon. He meets Alexander Calder and christens his kinetic sculptures “mobiles.” In September 1931, Reynolds, Brancusi, and Duchamp vacation together in Villefranche-sur-Mer. He becomes a member of the committee of the Fédération française des échecs

Man Ray: Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, 1927 (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut).

Marcel Duchamp: (Left to right) Duchamp, Mary Reynolds and Constantin Brancusi, Villefranche-sur-Mer, 8 September 1931 (Mary Reynolds Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago).

and its delegate (until 1937) to the Fédération internationale des échecs. Katherine Dreier discovers that the Large Glass, in storage since 1927, is broken.

1932–1933

Duchamp designs and publishes L’Opposition et les cases conjugées sont réconciliées, a chess treatise on endgame strategy co-authored with Vitaly Halberstadt. In June 1933, he participates in his last international chess tournament. That summer, he and Reynolds visit the Dalís in Cadaqués, Spain. Duchamp travels to New York in autumn and organizes a second Brancusi exhibition at the Brummer Gallery, where he meets Joseph Cornell.

1934

Duchamp assembles a selection of 93 notes pertaining to the Large Glass and has them meticulously printed in facsimile. Accompanied by reproductions of certain of his artworks, they are published in September in an edition generally known as the Boîte verte.

Use “delay” instead of picture or painting; picture on glass becomes delay in glass—but delay in glass does not mean picture on glass. It’s merely a way of succeeding in no longer thinking that the thing in question is a picture—to make a delay of it in the most general way possible, not so much in the different meanings in which delay can be taken, but rather in their indecisive reunion. “Delay”—a delay in glass, as you would say a poem in prose or a spittoon in silver.

Marcel Duchamp: La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même, known as la Boîte verte, 1934 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1935–1936

Breton’s text “Phare de la Mariée,” the first comprehensive study of the Large Glass, is published in Minotaure, the cover of which Duchamp designs. With financial help from Roché, Duchamp produces 500 sets of Rotoreliefs (disques optiques). These two-sided disks are a commercial flop when unveiled at the Concours Lépine. Duchamp also designs covers for George Hugnet’s La Septième face du dé and Cahiers d’art, which includes an article by Buffet-Picabia on his work. Certain of his readymades and early paintings are featured in group exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York. In summer 1936, Duchamp travels to Dreier’s Connecticut home to restore the Large Glass. He visits the Arensbergs in Hollywood.

Mary Reynolds and Marcel Duchamp: Binding for Ubu Roi (1921 edition) by Alfred Jarry, 1935 (Mary Reynolds Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago).

Walter Buschman: Katherine Dreier and Marcel Duchamp with La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (1915–1923), known as the Large Glass, at Dreier’s home, West Redding, Connecticut, 30 August 1936 (Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives).

Beatrice Wood: Marcel Duchamp at the Arensbergs’ home, Hollywood, 17 August 1936 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1937–1938

The Arts Club of Chicago mounts Duchamp’s first solo exhibition. He designs the entrance of Breton’s Gradiva art gallery in Paris. In March 1937 on Aragon’s invitation, he begins to write a weekly chess column for Ce Soir. He also designs a cover for the journal Transition. In January 1938, Duchamp (coaxed by Breton) collaborates on the mise en scène for the Exposition internationale du surréalisme at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris. He contributes a female mannequin (Rrose Sélavy) partially crossdressed in his own clothing. The same month, he installs works by Jean Cocteau for the opening of the gallery of Peggy Guggenheim

1939–1940

In April, glm publishes Duchamp’s collection of puns and spoonerisms titled Rrose Sélavy. He and Reynolds spend summer 1940 in Arcachon near Bordeaux with Suzanne Duchamp, Crotti, and the Dalís. He continues the painstaking work on his Boîte-en-valise (commenced in 1935), a suitcase containing 69 miniature replicas and reproductions of his oeuvre.

(Preceding double page) Marcel Duchamp: Boîte-en-valise, conceived between 1935 and 1941, series F, 1966 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Rrose Sélavy trouve qu’un incesticide doit coucher avec sa mère avant de la tuer ; les punaises sont de rigueur.

Rrose Sélavy et moi esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis.

Lits et ratures.

Du dos de la cuiller au cul de la douairière.

Konstantinos « Costa », Achilopulu: Mary Reynolds and Marcel Duchamp, London, 1937 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

À charge de revanche ; à verge de rechange. My niece is cold because my knees are cold.

1941

Duchamp completes the first examples of the deluxe edition of the Boîte-en-valise. Thanks to his friend Gustave Candel, a wholesale cheese merchant, he obtains an Ausweis, which enables him to transport elements for additional examples of his portable museum from the Occupied Zone in Paris to the Unoccupied Zone in Marseille. For almost a year, he lives with his sister Yvonne in nearby Sanary-sur-Mer, waiting for a visa to travel to the United States. He and Katherine Dreier bequeath the art collection of the Société Anonyme to Yale University.

1942

Arriving in New York on 25 June, Duchamp lives briefly with Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst. They introduce him to John Cage. Duchamp spends significant amounts of time with surrealist artists and writers who have escaped war-torn Europe, including, among others, Matta, Patrick and Isabelle Waldberg, Robert Lebel, Max Ernst, Kurt Seligmann, Yves Tanguy, and Breton. He collaborates with the latter on the exhibition First

Marcel Duchamp: Covers of the exhibition catalogue First Papers of Surrealism, Whitelaw Reid Mansion, New York, 14 October– 7 November 1942 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

John D. Schiff: Installation of the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism conceived by Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives).

Marcel Duchamp: Pocket Chess Set, 1943 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Papers of Surrealism, designing the catalogue and hanging hundreds of feet of string throughout the gallery to create a spider web–like effect. The Boîte-en-valise is placed on public view for the first time at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of This Century. Duchamp moves in with Stefi and Frederick Kiesler.

1943

Active in the French Resistance, Mary Reynolds escapes Occupied France, crosses the Pyrenees on foot, and lands in New York in January. Duchamp designs the covers of the second issue of VVV, for which he also serves as an editorial advisor. Vogue rejects Allégorie de genre for its cover. Duchamp meets Maria Martins, a sculptor and the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to the United States, and they commence a passionate love affair. In the fall, Duchamp moves into a studio at 210 West 14th Street. In addition to designing a pocket chess set, he appears in Maya Deren’s film Witch’s Cradle.

Marcel Duchamp: Covers of the second issue of VVV, 1943 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Ethel Pries: Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1946 (Archives Jean-Jacques Lebel).

1944–1945

Duchamp co-organizes and participates in the group exhibition The Imagery of Chess at the Julien Levy Gallery. In March 1945, a special issue of View devoted to him is published. It includes an article by Sidney and Harriet Janis in which the artist proclaims: “There is no solution because there is no problem.” He designs the covers, the back one featuring a note regarding the infra-mince, a concept first broached in 1937. George Heard Hamilton mounts an exhibition of the work of the Duchamp brothers at Yale. For the publication of Breton’s Arcane 17, the author and Duchamp create a window display at Brentano’s, which is transferred to the Gotham Book Mart following protests. In August, Duchamp visits Denis de Rougemont in Lake George, New York. The Museum of Modern Art purchases Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée, the first of Duchamp’s paintings to enter a museum.

Marcel Duchamp: Covers of View, March 1945 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1946

In secret, Duchamp begins Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage, a three-dimensional tableau installation that will take 20 years to complete. It features a nude female mannequin fashioned in part from casts of Maria Martins’s body. James Johnson Sweeney publishes the first extended interview with Duchamp in the Museum of Modern Art Bulletin. Duchamp returns to Paris in May.

1947–1948

Leaving Paris for New York in January, Duchamp allows Isabelle Waldberg to live in his rue Larrey studio. With Breton, he conceives the decor for the Exposition internationale du surréalisme in Paris. He and Enrico Donati fabricate the cover for the deluxe edition of the catalogue, consisting of a foam-rubber breast and a label that reads “prière de toucher” (please touch). Commenced in 1944 and containing an episode with Duchamp, Hans Richter’s film Dreams That Money Can Buy is released in April 1948. Following her husband, Maria Martins relocates to Paris.

Marcel Duchamp: Plaster study for the nude of Étant donnés, 1949 (Private collection).

(Preceding page) Maya Deren: Marcel Duchamp reinstalling the window display that he and André Breton conceived in honor of Arcane 17, Gotham Book Mart, New York, 18–19 April 1945 (Archives Jean-Jacques Lebel).

Maria Martins and her gold jewelry photographed and published in American Vogue, 1 July 1944 (Collection Francis M. Naumann).

1949–1950

Duchamp participates in the Western Round Table on Modern Art at the San Francisco Museum of Art. The Art Institute of Chicago exhibits selections from the Arensbergs’ collection, among them some 30 works of Duchamp’s. Collection of the Société Anonyme is published with 33 texts on various artists written by Duchamp. With Duchamp by her side, Mary Reynolds dies in Paris on 30 September 1950. He fabricates the first of several erotic objects based on Étant donnés. Maria Martins moves back to Brazil, and her relationship with Duchamp ends.

1951

In June, Duchamp meets Monique Fong in New York. Later in the year, he renews contact with Alexina “Teeny” Matisse, the former wife of Pierre Matisse. They soon become a couple.

(Left to right) Pierre-Noël, Paul, and Jacqueline Matisse, the children of Alexina “Teeny” Matisse, in front of their country house, Lebanon, New Jersey, circa 1940 (Archives Jacqueline Matisse Monnier).

Marcel Duchamp: Moonlight on the Bay at Basswood, 21 august 1953 (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

1952

(Preceding page) Marcel Duchamp in a wig in Man Ray’s studio, Paris, circa 1955 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Duchamp helps organize Duchamp frères & sœur at the Rose Fried Gallery. After Katherine Dreier dies on 29 March, he assists in mounting a memorial exhibition in her honor at Yale. In August, he addresses the New York State Chess Association, proclaiming: “I have come to the Marcel Duchamp and Jacqueline Matisse during the filming of personal conclusion that while all 8 X 8 by Hans Richter, Southbury, artists are not chess players, all Connecticut, summer 1952 chess players are artists.” (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1953

As an executor of Katherine Dreier’s will, Duchamp distributes her art collection among various museums. The Large Glass goes to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where the Arensbergs had bequeathed their collection in 1950. He installs the group exhibition Dada 1916–1923 at the Sidney Janis Gallery and designs the poster-catalogue. Louise Arensberg dies on 25 November, and Picabia five days later.

Marcel Duchamp: Poster-catalogue for the exhibition Dada 1916–1923, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, 15 April– 9 May 1953 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1954

Duchamp marries Teeny Matisse on 16 January, becoming the stepfather to her three children, Jacqueline, Paul, and Pierre-Noël. As a wedding gift, he presents her with Coin de chasteté. For the next five years, the Duchamps live in the former apartment of Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst at 327 East 58th Street. Walter Arensberg dies on 29 January. The Musée national d’art moderne in Paris acquires Les Joueurs d’échecs (1911), Duchamp’s first work to enter a French museum. Duchamp oversees the installation of the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and enlists Ilia Zdanevitch to make a new edition of the Boîte-en-valise. (His stepdaughter, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, will assemble the four subsequent editions.)

1955–1956

On 30 December, Duchamp becomes an American citizen. The following January, his first filmed interview, which James Johnson Sweeney conducts, is broadcast on American television. The Art Institute of Chicago publishes

(Preceding double page) Michel Waldberg: Teeny and Marcel Duchamp, 11 rue Larrey, Paris, circa 1957–1959 (Archives JeanJacques Lebel).

Marcel Duchamp: Coin de chasteté, 1954 (Private collection).

I considered painting as a means of expression, not an end in itself. One means of expression among others, and not a complete end for life at all; in the same way I consider that color is only a means of expression in painting and not an end. In other words, painting should not be exclusively retinal or visual; it should have to do with the gray matter, with our urge for understanding. This is generally what I love. I didn’t want to pin myself down to one little circle, and I tried at least to be as universal as I could. That is why I took up chess. Chess in itself is a hobby, is a game, everybody can play chess. But I took it very seriously and enjoyed it because I found some common points between chess and painting. Actually when you play a game of chess it is like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind by which you win or lose. The competitive side of it has no importance, but the thing itself is very, very plastic, and that is probably what attracted me in the game....I’m interested in the intellectual side of things, although I don’t like the word “intellect.” For me “intellect” is too dry a word, too inexpressive. I like the word “belief.” I think in general that when people say “I know,” they don’t know, they believe. I believe that art is the only form of activity in which man as man shows himself to be a true individual. Only in art is he capable of going beyond the animal state, because art is an outlet toward regions which are not ruled by time and space. To live is to believe; that’s my belief, at any rate. Marcel Duchamp, cited in a filmed interview with James Johnson Sweeney broadcast on American television in January 1956.

Surrealism and Its Affinities: The Mary Reynolds Collection, which Duchamp has helped compile. He also writes the preface and designs the bookplate for the catalogue.

1957–1958

Assisted by Duchamp, Sweeney mounts an exhibition devoted to the Duchamp brothers at the Guggenheim Museum. Duchamp designs the catalogue. The exhibition travels to the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, where the artist gives a major lecture entitled “The Creative Act.” On 30 January 1958, Jean Crotti dies. The Duchamps begin to spend summers in Cadaqués.

1959

The Duchamps move to an apartment at 28 West 10th Street. Robert Lebel publishes the first monograph and catalogue raisonné focused on Duchamp. The artist assists with the layout and fashions the deluxe edition, which features three new works, among them his only self-portrait. Michel Sanouillet edits Marchand du sel, the first significant compilation of

Richard Lusby: Marcel Duchamp signing the labels eau & gaz à tous les étages for the deluxe edition of Sur Marcel Duchamp by Robert Lebel, Paris, 23 September 1958 (Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives).

Duchamp’s writings and statements. bbc radio broadcasts an interview with Duchamp by George Heard Hamilton and Richard Hamilton. With Breton, Duchamp organizes the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (éros) in Paris.

1960

George Heard Hamilton and Richard Hamilton produce the first English translation of the Boîte verte. Duchamp participates in the symposium “Should the Artist Go to College?” at Hofstra College in New York. He meets Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and collaborates with Breton on the group exhibition Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain in New York, for which he designs the catalogue cover. Georges Charbonnier interviews Duchamp for RadiodiffusionTélévision française.

1961

Ulf Linde creates the first replica of the Large Glass (signed by Duchamp), which is exhibited in Stockholm. In March, Duchamp discusses the future of art at the

Marcel Duchamp: Autoportrait de profil, no. 000, 1957, inscribed to Teeny Duchamp (Private collection).

A point which I want very much to establish is that the choice of these “readymades” was never dictated by esthetic delectation. This choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste... in fact a complete anesthesia. [...] I realized very soon the danger of repeating indiscriminately this form of expression and decided to limit the production of “readymades” to a small number yearly. I was aware at that time, that for the spectator even more than for the artist, art is a habit forming drug and I wanted to protect my “readymades” against such contamination. Another aspect of the “readymade” is its lack of uniqueness... The replica of a “readymade” delivering the same message; in fact nearly every one of the “readymades” existing today is not an original in the conventional sense. A final remark to this egomaniac’s discourse: since the tubes of paint used by the artist are manufactured and ready made products we must conclude that all the paintings in the world are “readymades aided” and also works of assemblage. Marcel Duchamp, excerpts from “Apropos of ‘Readymades’” (1961)

Marcel Duchamp: Cover of the exhibition catalogue Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain, D’Arcy Galleries, New York, 28 November 1960–14 January 1961 (Achives Paul B. Franklin).

Philadelphia Museum College of Art, stating: “The great artist of tomorrow will go underground.” The American Chess Foundation holds a benefit auction in New York spearheaded by Duchamp. He receives an honorary doctoral degree from Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

1962–1963

Assisted by Teeny, Duchamp continues work on Étant donnés. Villon dies on 9 June. Suzanne Crotti dies the following September. Duchamp designs the poster for the fiftieth anniversary exhibition of the Armory Show in Utica, New York. In October 1963, Walter Hopps mounts the first major retrospective of Duchamp’s work at the Pasadena Art Museum. The artist designs the poster.

1964–1965

With Duchamp’s consent and participation, the Italian art dealer Arturo Schwarz has fabricated a limited edition of replicas of the readymades. Jean-Marie Drot’s film Jeu d’échecs avec Marcel Duchamp, containing interviews

Marcel Duchamp in Las Vegas, Nevada, October 1963 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Mark Kauffman: Marcel Duchamp playing chess on a wall-mounted chessboard, Cadaqués, 1960. (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

with the artist, is broadcast on French television. The Duchamps move into Suzanne Duchamp’s former studio at 5 rue Parmentier in Neuilly-sur-Seine in summer 1964, which they inherited after her death. In January 1965, Cordier & Ekstrom gallery hosts a retrospective that features several works never before exhibited. Duchamp designs the invitation and the catalogue cover.

Marcel Duchamp on the terrace of his apartment in Cadaqués, circa 1964–1965. (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1966

In February, after two months of methodical work, Duchamp and Teeny finish moving Étant donnés and the rest of the contents of his studio on West 14th Street to a new space at 80 East 11th Street. The same month, Andy Warhol films Duchamp at the opening of Hommage à Caïssa, a chess exhibition the latter staged at Cordier & Ekstrom. Richard Hamilton organizes the first major European retrospective of Duchamp’s work at the Tate Gallery in London, producing a second replica of the Large Glass for the occasion. In Paris, Duchamp meets his grown daughter, Yo Savy. He completes Étant donnés, having sold it to William Copley’s Cassandra Foundation with the understanding that after his death it

Marcel Duchamp: Cage Czech, 1966 (Private collection).

will be donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He also fashions a manual of instructions explaining how the work should be dismantled and reassembled.

1967

Pierre Cabanne publishes his extensive interviews with Duchamp in January. Cordier & Ekstrom exhibits À l’infinitif, generally known as the Boîte blanche, a collection of 79 unpublished notes by Duchamp. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen presents an exhibition devoted to the Duchamp siblings. In June, Duchamp’s readymades are presented at Galerie Claude Givaudan in Paris. The artist designs the invitation and poster. Duchamp arranges for Yo Savy to exhibit her paintings in November at the Bodley Gallery in New York.

Marcel Duchamp: Poster for the exhibition Ready-mades et éditions de et sur Marcel Duchamp, Galerie Claude Givaudan, Paris, 8 June– 30 September 1967 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Can one make works which are not works of “art”? Look through a dictionary and scratch out all the “undesirable” words. Perhaps add a few. —Sometimes replace the scratched out words with another. Use this dictionary for the written part of the glass.

Yo Savy (née Yvonne Serre) with her husband, Jacques Savy, Teeny, and Marcel Duchamp (her father) at the Savy’s home, Autheuil-enValois, circa 1966–1967 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

Marcel Duchamp: Text in homage to Yo Savy in the brochure for the exhibition Yo Sermayer, Bodley Gallery, New York, 14–25 November 1967 (Archives Paul B. Franklin).

1968

In February, the Duchamps and John Cage participate in Reunion, a musical performance coordinated by the latter in Toronto. The Duchamps go to Buffalo in March to see the premiere of Merce Cunningham’s dance Walkaround Time. Jasper Johns designs the sets, which are based on the Large Glass. In the early hours of 2 October, after dining with Man Ray, his wife, Juliet, and Robert and Nina Lebel, Duchamp dies at his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine. His ashes are interred in the family plot in Rouen. His epitaph, which he wrote, reads: “d’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (besides it is always the others who die).

1969

Respecting Duchamp’s wish that Étant donnés be publicly unveiled only after his death, the Philadelphia Museum of Art inaugurates the work on 7 July. Arturo Schwarz publishes a catalogue raisonné devoted to Duchamp.

Marcel Duchamp: Le Bec Auer, 1968 (Archives Marcel Duchamp).

1973–1974

The Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York co-organize the first posthumous retrospective of Duchamp’s work.

1977

As its inaugural exhibition, the new Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris presents the first French retrospective of Duchamp’s work.

Poster for L’Œuvre de Marcel Duchamp, the inaugural exhibition of the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1 February– 2 May 1977 (Collection Jean-Luc Thierry).

(Preceding double page) Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage, 1946–1966, views of the exterior and interior (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

Véra Cardot and Pierre Joly: Marcel Duchamp with his back to the door that is neither opened nor closed, 11 rue Larrey, Paris, 2 May 1967 (Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris).

To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing. If we give the attributes of a medium to the artist, we must then deny him the state of consciousness on the esthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it. All his decisions in the artistic execution of the work rest with pure intention and cannot be translated into a self-analysis, spoken or written, or even thought out. [...] In the last analysis, the artist may shout from all the rooftops that he is a genius; he will have to wait for the verdict of the spectator in order that his declarations take a social value and that, finally, posterity includes him in the primers of Art History. I know that this statement will not meet with the approval of many artists who refuse this mediumistic role and insist on the validity of their awareness in the creative act—yet, art history has consistently decided upon the virtues of a work of art through considerations completely divorced from the rationalized explanation of the artist. [...] In the creative act, the artist goes from intention to realization through a chain of totally subjective reactions. His struggle toward the realization is a series of efforts, pains, satisfactions, refusals, decisions, which also cannot and must not be fully self-conscious, at least on the esthetic plane. The result of this struggle is a difference between the intention and its realization, a difference which the artist is not aware of. Consequently, in the chain of reactions accompanying the creative act, a link is missing. This gap which represents the inability of the artist to express fully his intention; this

difference between what he intended to realize and did realize, is the personal “art coefficient” contained in the work. In other words, the personal “art coefficient” is like an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed. To avoid a misunderstanding, we must remember that this “art coefficient” is a personal expression of art “à l’état brut,” that is, still in a raw state, which must be “refined” as pure sugar from molasses, by the spectator; the digit of this coefficient has no bearing whatsoever on his verdict. The creative act takes another aspect when the spectator experiences the phenomenon of transmutation; through the change from inert matter into a work of art, an actual transubstantiation has taken place, and the role of the spectator is to determine the weight of the work on the esthetic scale. All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act. This becomes even more obvious when posterity gives its final verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten artists.

This chronology was written by Paul B. Franklin. Aube Breton-Elléouët, Oona Elléouët, and Seven Doc would like to thank all those who made this publication possible, especially Jacqueline Matisse Monnier. All artworks by Marcel Duchamp: © Succession Marcel Duchamp, 2009, ADAGP, Paris. All artworks by Man Ray: © Man Ray Trust, 2009, ADAGP, Paris. © All rights reserved. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of the works reproduced herein. We apologize for any omissions that inadvertently may have occurred. Seven Doc layout and graphic design: Thomas Castex (Front cover) Katherine Dreier: Marcel Duchamp on the balcony of the Hôtel Brighton, rue de Rivoli, Paris, summer 1924 (Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives). (Back cover) Marcel Duchamp: Rotative demi-sphère (optique de précision), 1924 (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

Man Ray : Marcel Duchamp, circa 1925 (Private collection).

![Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century [Fourth ed.]

0262111365, 9780262111362](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/marcel-duchamp-artist-of-the-century-fourthnbsped-0262111365-9780262111362.jpg)

![Marcel Duchamp: The Bride stripped bare by her bachelors, even (Art in context) [1 ed.]

0713902779, 9780713902778](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/marcel-duchamp-the-bride-stripped-bare-by-her-bachelors-even-art-in-context-1nbsped-0713902779-9780713902778.jpg)