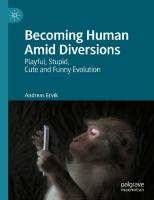

Becoming Human Amid Diversions: Playful, Stupid, Cute and Funny Evolution. 9783031138768, 9783031138775, 3031138767

This book develops a philosophy of the predominant yet obtrusive aspects of digital culture, arguing that what seems lik

147 51 5MB

English Pages 299 [395] Year 2022

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

Front Matter

1. Attractive Screens

2. Microbe Computing

3. Vegetative Games

4. Worldwide Fungi

5. Social Petworks

6. Human Tribes

7. Becoming Humidity

Back Matter

Citation preview

Andreas Ervik

Becoming Human Amid Diversions Playful, Stupid, Cute and Funny Evolution

Andreas Ervik Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

ISBN 978-3-031-13876-8 e-ISBN 978-3-031-13877-5 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13877-5 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Cover illustration: Ryouchin | Getty Images

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

Becoming Human Amid Diversions “Develops its own original and even idiosyncratic trajectory through the scholarship and analysis. It is playful in its choice of case studies and ambitious in its drawing on material and sources from beyond the usual media / communications literature. It is certainly timely, recent transformations of the digital and networked mediasphere need this book’s critical assessment and explanation of attention, engagement, everyday temporality, play, etc. Whilst some of the examples may feel dated in five years or so, the underlying argument and framing will I think prove longer-lived.” —Dr Seth Giddings, University of Southampton, UK “Stupid but cute, distracted and fungal, burned out and playful: this is an inventive and sometimes mischievous media theory that embraces ecology, artifice and delight to propose an art of living with the internet we know today.” —Matthew Fuller, Professor of Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London

Acknowledgments This book would not have been possible without the PhD funding provided by the Department of Media Studies at the University of Oslo. My sincere gratitude to Liv Hausken and Matthew Fuller, for precise and poignant guidelines and advice. My deepest appreciation to Tony D. Sampson, Levi Bryant, Sean Cubitt, and Eivind Røssaak for substantial responses at various stages of the project. Thank you, Patrick Jagoda for generously extending an invite from the University of Chicago, and for invaluable support and feedback. My gratitude for valuable comments in workshops and conversations to Gertrud Koch, Geoffrey C. Bowker, Michael Marder, Ina Blom, Aurora Hoel, Stéphane Aubinet, Desiree Foerster, Maja Bak Herrie, Khalid Azam, Truls Strand Offerdal, Ellef Prestsæter, Marlene Wenger, and several others. Special thanks to colleagues Jon Inge Faldalen, Steffen Krü ger, Timotheus Vermeulen, Kim Wilkins, and Gry Rustad. I am indebted to research groups, especially Media Aesthetics at the University of Oslo. A big thanks to my family and to friends. Finally, my deepest heartfelt gratitude to my wonderful partner Siv.

Contents 1 Attractive Screens 2 Microbe Computing 3 Vegetative Games 4 Worldwide Fungi 5 Social Petworks 6 Human Tribes 7 Becoming Humidity Bibliography Index

List of Figures Fig.1.1 Screenshot from the app Forest.The app helps people stay away from their phone, with the incentive being animated trees growing in fields during set periods of not using the phone

Fig.2.1 Screenshots from Barricelli’s digital ecosystem of symbioorganisms, reprogrammed and described by Alexander Galloway:“Each swatch of textured color within the image indicates a different bionumeric organism.Borders between color fields mean that an organism has perished, been borne, mutated, or otherwise evolved into something new”

Fig.2.2 Constantin Mereschkowsky offered a model of the tree of life with crisscrossing lines of descent in 1905 (Wikimedia Commons)

Fig.2.3 Stills from a YouTube video showing Brice Due’s OTCA metapixel, running in John Conway’s Game of Life.The documentation video starts up close and then gradually moves out to reveal structural recursive patterns.Emerging from the interactions between cells and the rule set of Game of Life, the metapixel gives rise to a higher-level game abiding to the same rule set; however, these rules are themselves also emergent properties of the running system.Video posted by Phillip Bradbury

Fig.3.1 A screenshot from Nintendo’s Super Mario Maker 2 (2019), showing a trail of Mario’s movements

Fig.4.1 Screenshot of clickbait from galacticbuzz.com, showing some attractors for a bait-clicking population:winning money, fantasy

combat, phallic pareidolia, and especially female faces, and female bodies in semi-undress

Fig.4.2 An xkcd webcomic by Randall Munro shows the irresistible urge to engage in and continue debates online, especially when it is emotionally aggravating, and the discussion will bring nothing but further disagreement

Fig.5.1 Picture from the Facebook profile of Lil Bub, a profile with 3 million Facebook likes, courtesy Mike Bridavsky

Fig.5.2 Still from a video posted September 25, 2020, by Twitter user @bloodtear_(account has since been deleted)

Fig.5.3 Imagery produced using the artificial neural network Deep Dream, which “hallucinates” the visual presence of animals and nonanimate objects in otherwise inconspicuous visual patterns.Image by Mordvintsev et.al./G oogle DeepDream

Fig.5.4 Doge presenting the emotional states of music in minor and major scales.Original photo by:Atsuko Satō

Fig.5.5 Still from a video posted to Lil Bub’s Facebook profile, showing Lil Bub being fed by its owner, Mike Bridavsky, nicknamed “Dude,” who also puts pain relief medication into the cat’s food

Fig.6.1 A political compass showing primitivist political positions, along an axis of right to left and authoritarian to libertarian.The positions are generally rendered ridiculous, with crude illustrations

accompanying them.Sourced from Know Your Meme, originally posted by user pangolinshell to r/PoliticalCompassMemes

Fig.6.2 An image macro attributing the election of Donald Trump to memes.Sourced from Know Your Meme

Fig.6.3 Image macro made with the website Imgflip’s meme generator, offering a funny prospect for the end of Trump’s presidency

Fig. 7.1 Emoji displaying the gas, liquid, and crystal states of H2O

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022 A. Ervik, Becoming Human Amid Diversions https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13877-5_1

1. Attractive Screens Andreas Ervik1 (1) Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Andreas Ervik Email: [email protected]

Prologue Bzzt bzzt! The vibration motor in the rose gold-framed, Samsungbranded, black rectangle buzzes. Inattentively my hands move away from typing. My gaze shifts from the computer screen, and the Word document I am writing, to the smaller screen of the phone. A change of screenery. Maybe a friend has sent a funny picture? Nope, just junk mail. I should be working, not procrastinating. To regain focus, I open the app Forest (see Fig. 1.1), which lets me set a timer, ranging from a quarter to a couple of hours, in which a cartoon tree grows. If I check the phone during this period, the tree will wither, leaving a permanent dead tree in the digital fields of the app. This incentive is effective, as I have yet to kill a single tree. But the reason may not necessarily be less procrastination.

Fig. 1.1 Screenshot from the app Forest. The app helps people stay away from their phone, with the incentive being animated trees growing in fields during set periods of not using the phone

As I return to the laptop, my muscle memory knows the shortcut command to change applications. And hardly noticing, my fingers make the switch from Word document to Firefox web browser. I find myself

scrolling down my Facebook feed, pausing at a video, bemusedly watching a cute animal stumbling around, before scrolling to another, ridiculing the latest fumbling of political leaders. Web browsers can be equipped with extensions like Stayfocused, letting me restrict access and limit the amount of time spent on specific sites. Another attention seeker lies waiting in my backpack, however, ready to interrupt the Stayfocused workflow: Nintendo’s portable gaming device Switch. While supposed to be restricted to work commute, it is hard to keep fingers keyboard-tied when they could embark Super Mario on his latest odyssey. Although specific to me, this account of diversions is undoubtedly familiar to anyone equipped with one or more screens to stare at during their workday, as well as during leisure hours, letting people send important e-mails from the subway, or even watch videos while on the toilet. The junk mail, animal clips, political jokes, and videogames are diversions in a computerized and networked environment where the use of time and amount of procrastination is ours to decide and limit. The computerized, screen-centered, and networked living seems to ruin our attention span, leaving us at the whims of notifications, as we constantly check our screens. No wonder then that one today might wish to reduce these distractions, both individually and for digital living in general. My approach in this book is different. Rather than taking diversions as pervasive aspects of digital living to avoid, I seek to form knowledge of how and why they function the way they do. I seek to understand what are simultaneously some of the most mundane and the most popular elements of digital living. The central question for this book is therefore: Why are diversions so important for digital living today? I will attempt to answer this through considering, more specifically: What makes videogames, mindless web browsing, cute animal images, and political mockery divert attention? The book is committed neither to assist nor negate diversion development. Potential side effects, however, include how it could offer a smart manual on how to profit from diversions. But it might be equally instructive for curbing individual dispositions toward diversions, or aid opposition against companies profiting from them. The proceeding section considers how digital distractions are usually framed and approached. I review certain strands of distraction research, and problematize some preconceived notions. Commonly, distractions are rendered aspects of digital living to be avoided and reduced, as they distract from what we ought to direct our attention to. I propose instead

to conceptualize these media forms as diversions, which will allow a less antagonistic framework. The section closes by considering how diversions, as prominent aspects of digital media, may also influence the possibilities for developing theoretical reflections today. Rather than lament this as a problem, I develop an approach of not only seeking to understand diversions, but to also learn from and think with them. When masses of people get to decide what they want to spend time on, the result is diversions, in the form of videogames, Internet browsing, social network scrolling and swiping, and the sharing of images and engaging in discussions. Having shifted the perspective from distractions to avoid to diversions to reflect with, I propose that diversions provide insights into what it means to be human. Drawing perspectives from systems theory, realist philosophy, and biology, diversions will be rendered here as important not only for being human today, but for the evolution of our species. The importance of diversions today indicates their influence on the process of becoming human. The introduction concludes by presenting an outline of the objects of analysis and the central queries of each following chapter. The objects range from the beginning of digital computation and networking to the present: computer programs by Nils Aall Barricelli from the 1950s and Game of Life by John Conway from 1970; the classic videogame Super Mario Bros. from 1985; networks, from the ARPANET in the 1970s to the World Wide Web in the 1990s, with a focus on clickbait in Internet browsing in the present; social networking and the Facebook accounts of celebrity dog Boo and cat Lil Bub, as well as YouTube videos of pets; the knowledge database of funny imagery Know Your Meme; and the activities on online forums 4chan and Twitter.

Amid Diversions Philosopher and former Google advertising strategist James Williams presents what seems to be a dominant perspective on digital distractions.1 Williams organizes his reflections with an anecdote about the ancient philosopher Diogenes. As Diogenes was relaxing one day, Alexander the Great came up to him, offering to fulfill any one wish he might have. Diogenes replied: “stand out of my light.” Williams takes this as a critical lesson, and a retort against those who may be considered as standing in our light today, clouding our ability to concentrate: the platforms and companies of digital distractions. Williams is far from alone in his concerns. As computers and networks connect an unprecedented number of people, these people seem to have become overwhelmed with the immensity of produced and shared audiovisual material. People find themselves distracted from whatever they were supposed to be doing to whatever triggers their attention: shifting from focused work to trivial play; from thoughtful contemplation to mindlessly browsing the Internet, from mature behavior to infantile cuteness; from reasonable discussion to ridiculous mockery. It would seem that people need to avoid the trivial but exciting, in order to stay focused on what by comparison might be significant though tedious. To combat the perceived lack of control, people have started digital detoxing. To get work done in such an environment, it might indeed be best to periodically opt out—turning off notifications, disconnecting, and even shutting down devices. As Williams reminds, we are not simply addicted to our screens; the software and networks they connect to do not belong to us. While the buzzing phone might seem a personal nuisance, tech companies have incentives for guiding behavior, as their revenues depend on applications keeping people in addictive activity loops. Williams is far from the only former employee of a big tech company or philosopher, who has spoken out about technology hijacking our minds, and, as a consequence, potentially threatening individual human freedom and by extension our societies.2 Digital technology could perhaps be considered exploitative capitalism, ushering in a new dark age.3 Should we call our current period an age of distractions? This could be taken to indicate that, although personal adjustments could be

effective in terms of combating procrastination, calls for society-wide changes might be required. Withholding evaluation on the necessity for personal or political changes, I think it is necessary to form an understanding of what distractions are. Sociologist William Bogard offers a productive perspective, pointing to how distractions tie together two seemingly distinct logics. The first of these is how distractions offer escape. Distraction can be forms of relief, allowing you to slip away from whatever you should be doing. You might be reading this book, but after a while you need some escape from its monotony, so you look at your phone. Secondly, Bogard renders distractions as a form of capture. Screens are captivating. Before you know it you’ve watched hours upon hours of TikTok videos or scrolled endlessly through Twitter. When did distractions, with their potential for captivating escape, become a problem? Starting from popular discourse of distractions, one might get the impression that smartphones, or perhaps networked computing, ushered in the age of distractions. The Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma (2020), traces the problems to the business model of social networks, encapsulated in the catchphrase “if you are not paying for the product, you are the product.” This notion is traceable to the artwork, “Television Delivers People,” by Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman from 1973. As indicated by its title, it referred to an earlier media technology delivering viewers to advertisers. The Netflix documentary fails to mention this point, and does not draw attention to itself as a development of television, and perhaps part of the problem addressed. More broadly, this brings the question of whether a supposed age of distractions began with television, and were carried over into networked computing. Also published in the 1970s were the writings of Herbert A. Simon on attention economies, in which “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”4 But media are problematized as distractions even further back in time. In his aesthetic theory from the 1930s, Walter Benjamin describes how the editing in cinema distracts, as opposed to the contemplative gaze upon a painting.5 The age of distraction could be traced to industrialized production, and in the 1940s, critical theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer coined the term culture industry, criticizing the

standardized industrialized culture of film, radio, and popular music.6 This factory-like cultural production manipulates masses into passivity by creating false psychological needs. Art theorist Jonathan Crary continues the identification of distractions as emerging in early modernity, and connects the struggles over attention with the need for productive and efficient workers, writing that “[s]ince the late 1800s. the problem of attention has remained more or less within the center of institutional empirical research and at the heart of the functioning of a capitalist economy.”7 Might the multitude of modern media offering distractions indicate that rather than an inconsequential side effect of media development, there could perhaps be a fundamental relation between media and distractions? Moving from images to writing, there are those that would present even this as a distraction. Philosopher Jean Paul Sartre provides a description of the ambivalent function of the newspaper in public transport in a manner reminiscent of the use of a smartphone or a portable gaming device today: “to isolate oneself by retaining the paper is to make use of the national collectivity and, ultimately, the totality of living human beings … in order to separate oneself from the hundred people who are waiting for or using the same vehicle.”8 Bogard suggests that “[t]here is no reason to think that print is any less distracting than electronic media, or that modern forms of spectacle distract the masses more than ancient ones.”9 Media theorist Yves Citton has traced concerns of attention to complaints over book overabundance already in the eighteenth century, and the art of rhetoric even suggests an ancient need for speakers to seize the limited resource of attention.10 In the ancient dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus, writing is rendered a distraction from face-to-face interaction, which problematically makes possible learning without a teacher that authorizes what is true and who should learn. As Phaedrus states: “What a wonderful kind of diversion you’re describing, Socrates—that of a person who can amuse himself with words …—compared with the trivial pastimes of others.”11 Despite the threat historically posed by books to attention, it would seem today that distractions come from screens. And indicated by technological fixes such as removing the color from the phone screen, attractive entrapments are dominantly visual. While writing also functions as distractions, and offers captivating escape, it has according

to media scholar Marshall McLuhan been framed as a rational technology: “we have confused reason with literacy, and rationalism with a single technology. Thus, in the electric age man seems to the conventional West to become irrational.”12 This framework seems central for distractions framed as threats to sustained attentive focus, of either work or leisure, of reading, or today even of watching a whole movie without checking the phone. Rather than our current age as an age of distractions, this brief historical swipe indicates a more fundamental relation between humans and media distractions. I consider therefore that we live amid media distractions. The preposition here indicates that people are surrounded by as well as exist in the middle of and against a backdrop of media distractions. This perspective is related to Benjamin’s thoughts on architecture and film, in which he develops a notion of reception in a state of distraction, of being attentive to and letting something recede into background through habit.13 Media is part of the architectural backdrop of existing today. Smartphones are habitual to the point that one might wonder where one put one’s phone, all the while reading an article on it. But smartphones will also make themselves known, demanding immediate attention through sounds indicating some kind of update. If distractions are fundamental to the way media functions, should they even be considered distractions? As a concept, distraction is linked to attention, even a specific understanding of attention. This is the sustained and voluntarily controlled form of attention, rather than any form of dispersed and responsive attention. This frames distractions as by default negative, unwanted, and obtrusive. The terms distraction and attention seem to have a built-in preoccupation with separating the proper from the improper focus. This lends itself well to the critical perspectives, be they personal or political, which consider distractions as lapses from what we ought to concern ourselves with: control over distractions, working over playing, knowledge over stupidity, maturity over cuteness, and responsibility over humor. Distractions are regularly framed as corporate hijackings of common urges, and thereby turn into something simultaneously irrelevant and in urgent need of removal. Yet as anyone with a smartphone will readily attest, distractions might also be desirable. Distractions offer respite from unwanted situations, such as a dreary task we would rather not engage in. Procrastination can be

joyous, filled with discovery and novel excitement for the wonderful peculiar things and beings of the world. Instead of identifying the problems of distractions, and the necessity of telling tech companies to stand out of one’s light I am interested here in what draws us toward them. A new approach therefore becomes necessary. An initial approach is to designate these media forms not as distractions, but rather as diversions. This term retains the notion of something being shifted in its course. Yet this something is no longer only human attention, as the term diversion denotes any form of system shifted in its course. This also indicates an ambivalent frame of evaluating, from the evidently negative perspectives on distractions to the more open-ended possibilities resulting from something diverting to something else. The notion of diversion influences also how attention is framed. When paired with distractions, attention is something over which individuals have, or should have, control. Instead, I open here to an understanding that as humans, we exist amid diversions, where control might reside not in us as individuals but be distributed into a myriad of different objects and relations. As identified in the discourse on distractions, an important part of existing amid diversions is how they influence possibilities of reflection. Considering media forms as distractions makes their influence seem wholly negative. For the reader and writer alike, distractions take attention away from books to the exciting audiovisual splendor of screens. As diversions, however, their influence becomes more indeterminate, with the capacity not simply to negate but to shift the course of something. A historical example of such consequences from technological development is pointed out by media theorist Friedrich Kittler. He observed how the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche switching to a typewriter changed his writing “from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style.”14 Likewise, digital diversions may influence writing today, by giving rise to the nagging question: How could I ensure that readers do not simply divert into other media? One approach to such pressure is to criticize readers lacking the determination, intelligence, maturity, or responsibility needed for comprehending complex arguments. Since my interest here instead lies in considering how diversions attract, a less dismissive attitude would be a more constructive point of departure.

One such point of departure is found in the work of poet and media scholar Kenneth Goldsmith, who has both taught a course and written a book titled Wasting Time on the Internet. Goldsmith frames time spent surfing as wasted, yet enthusiastically champions the ways in which network makes people engaged, creative, and socially connected.15 This is a welcome counter to the social stigma and guilt which is usually attached to existing amid diversions. What if the problem is not the diversions themselves, but rather the organization of societies in which school kids, students, and adult workers are glued to screens, but at the same time have to avoid the most enjoyable things that these screens can be used for? In Goldsmith’s class a range of ideas for wasting time on the Internet together were brainstormed and tested, ranging from public sessions of web browsing to pranks and games such as uncovering every detail possible online on someone and sharing the information with them, or fifteen-minute competitions of filling the most expensive shopping cart on Amazon.16 Although Diogenes was introduced at the beginning of this section in opposition to developers of distractions, he also offers perspectives for thinking with diversions. Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has resurrected the cynicism (meaning dog-like) of Diogenes, rendering him as a philosopher who talks “in a dialogue of flesh and blood,” and thus creating a sort of embodied philosophy which “does not speak against idealism, it lives against it.”17 Diogenes entered philosophy with other parts of the body than simply the head, with his mind and mouth, being a philosopher not only of thought or dialogue. For instance, when asked to listen to someone lecturing about movement being illusory, Diogenes stood up and walked away. His refusal to leave material reality out of discussions turns Diogenes into an obstacle for philosophical thought. Plato referred to him as a Socrates gone mad. This criticism turns into a virtue, however, as it to a certain extent levels him with someone regularly credited with founding Western philosophy. Diogenes initiates a counter-philosophy, where arguments may take the form of actions. How would philosophical inquiry have developed if, instead of Socrates, it followed from Diogenes? Diogenes left no written sources, which might be an indication of how his form of arguing refrains from passing the threshold from living into writing. Perhaps his way of doing philosophy is less functional when inscribed. This philosophy might

divert proper academic discourse; it might be anathema to books, with the written word only able to gesture toward it. Such gesturing is found in the work of philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who contends that talking is dirty, because it relies on charm more than rational argument.18 Writing with diversions is a dirty way of writing, infusing arguments with charm. My goal is to consider inattentiveness productively, to learn from, as much as understand, diversions. This could furthermore be considered a prospect of experimental humanities. Gaming scholar Patrick Jagoda identifies how this subfield goes beyond analysis and, with improvisation and problem-making, formulates unexpected responses to contemporary conditions.19 With Deleuze, such experimental methods are encapsulated as a way of writing for readers, in a double sense—toward their attention and in their absence. Deleuze is particularly intrigued with the potential of writing in place of someone illiterate or insane, whereas the alignment here will be with less exceptional people. I set out to write in place of the digitally diverted, those who write and read mostly in short bursts of multichannel audiovisual conversation, as opposed to the long-form monotony of a monograph. If you would rather engage with diversions than read theory, then this work of theory is for you! The endeavor of writing theory for diverted readers might be described, with aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai, as a way of acting zany.20 Traditionally the zany is a comic fiction character, often a servant of some kind. This worker is put in an insecure and unstable position, given opposing or even impossible tasks. The zany nevertheless tries to please, but their situation becomes increasingly desperate. The zany is pushed toward doing more than necessary, which inevitably leads to spectacular failure. Tasking myself with writing theory for diverted readers is itself a zany prospect. It seeks potential for reflection, somewhere between the rigorous and the ridiculous. How am I setting myself up to fail spectacularly? Read on!

Becoming Human The concept of diversions shifts these forms of media from something we should avoid to something we exist among. Becoming human is today a process occurring amid diversions: From the toddler intuitively grasping screen interfaces and to some extent preferring them over other playthings, to school children struggling to learn alongside networked devices, from teens on their phone during class to students playing videogames instead of preparing for seminars. As distractions these are fleeting, feeble, and foolish. They are problems of inattentiveness—a mess that we need to find a way out of. As diversions they are instead injected into situations and lives with a greater sense of significance. Becoming human today involves infuriation over political disputes on Twitter, it involves the overwhelming urge to squeeze-hug a kitty, and it involves failing to resist playing videogames during lunch hours. Rather than trivialities, these media forms shape development, and as such they can offer indications of how we become human amid diversions. I find the philosophy of Manuel DeLanda helpful for conceptualizing diversions as shapers of development.21 Central for DeLanda is a form of population thinking, which offers a reorientation away from preoccupations with the individual experience of being alone with one’s phone. One is never actually alone with a phone. Anyone scrolling through social networks does so amid a population of others engaged in processes of tapping keys or swiping screens. Shifting the focus from the individual with their attention, to population dynamics, renders diversions not as the personal choices you make, but as the result of myriads of choices made by hordes of people. Diversions are thereby not reducible to the intention of producers, who are also responding to and attending to the behavior of users. If not merely through the manipulation of producers, what makes entire populations tend toward and converge on similar things? While individuals engage with multiple different things, showing great subjective variation, populations converge around common interests. What do networked computing indicate as base human interests? Humans assemble with computers, tending toward play, stupidity, cuteness, and humor. In the coming chapters I will synthesize answers to questions of why diversions attract through the sub-questions of what characterizes

assembling with something, what constitutes play, games, and fun, what characterizes stupid behavior, what makes someone cute, and what makes people laugh. In defining diversions, I will potentially disrupt conventional notions. Among disruptions is the way I shift the difference between diversions and what are commonly framed as their opposites. Play is a diversion of work, as it involves features of working such as difficulties effort, concentration, and perseverance, without fully coinciding with working. As I will show, stupidity likewise shares similarities with intelligence, especially in how it enables problemsolving, while nevertheless being clearly different from intelligence. Cuteness may seem like it has little to do with mature humans, but as will become clear, we retain cute appearance and behavior into adulthood. Humor seems like it would be entirely inappropriate in responsible discourse, but need not be completely separated from it. Diversions differ from their opposite tendencies without fully diverging from them. Diversions precede networked computing. This holds true for diversions in general, as well as for the specific diversions I have identified. These aspects are base human tendencies, which become amplified by networked computing. The question of how diversions shape processes of becoming human today thereby turns into one that is deeper and wider, to speculatively consider: How have diversions shaped the process of becoming the human species? Far from insignificant distractions, diversions could offer indications into prehistoric human attention, to what has shaped our species evolution. What has made play, stupidity, cuteness, and humor something we so regularly attend to? Drawing interdisciplinary perspectives from biology, I will in the following chapters examine the potential significance of play, stupidity, cuteness, and humor, for becoming human. My focus on becoming human amid diversions takes cues from posthumanist philosophy, in that it destabilizes the privileged and exceptional position of humans as beyond all other organisms.22 Instead of conceptualizing the process as a posthuman shift, the framework here comes from the theory of evolution, which fundamentally destabilized anthropocentrism by showing the relatedness of all organisms. Approaching contemporary media diversions through the evolution of organisms would seem to naturalize technological development, rendering this development as inevitable and following prescribed rules.

I contend that such an understanding misconceives nature as an unvarying stasis, against which human ingenuity unfolds with dynamic freedom. This is simply not the case, as nature unfolds with dynamic variability, and human behavior follows certain predictable tendencies. Becoming human is a process occurring amid non-human objects, tools, and technologies. Philosopher Bernard Stiegler considers technology as foundational for the evolution of our species.23 In Stiegler’s account humans are a fundamentally technologically mediated species; the origin of the species is in tool usage. This also shifts the question from who to what evolves, extending from the body schemas of humans to the tools the species use and surround themselves with. Such development includes tools for the purpose of hunting, cooking, and food preservation or forms of protection and shelter in the form of clothing and homes. It also includes cognitive environments provided by entertainment, myths, and knowledge offered through the development of oral storytelling, cave markings, weaving, painting, printed words, phonography, photography, and cinematography, as well as computer programs and network streams. When presented as distractions, any development in these cognitive environments can be framed as posing threats to the existing order. As diversions, they are prospects to be studied to understand humans. The perspective adopted here aims to bridge the opposing notions of McLuhan’s influential notion of media as “extensions of man” versus that of Friedrich Kittler’s perspective that “media determine our situation.”24 These two perspectives can be summarized as technological naturalization versus determinism, the former considering that media will only “attach itself to what we already are,” whereas the latter claiming that in the digital era “senses turn into eyewash.”25 Instead of framing these as opposing accounts, diversions show at once how sensory experiences are increasingly determined by networked computing and screen-centered living, but also how diversions are formed by tapping into evolved behavioral tendencies. Evolution theory teaches not only that humans are descended from primates, but, in the words of media theorist Jussi Parikka, that “each human being is a recapitulation of the whole of the animal kingdom, the potential of any animal whatsoever.”26 The process of becoming human is one which contains traces of the entire prehistory of humans, but also

the evolution of other animals. We retain evolved patterns of behavior, such as tendencies toward play, stupidity, cuteness, and humor, which networked computing acts as amplifiers of. In much the same manner, humans themselves could be considered amplifiers of tendencies of animals. Extending the perspective of Parikka from animals to include the evolution of all organisms, becoming human is a process which retains and develops the bodily organizations, ecological relations, and behavioral tendencies of all sorts of organisms. A central question here becomes, how do also other organisms tend toward play, stupidity, cuteness, and humor? In the following I explore processes of becoming human, both today and in deep evolutionary time. This will be done through discussions with perspectives from biology on a range of different organisms, including microbes, vegetation, fungi, mammals, and human huntergatherers. Central questions to which I offer philosophical speculation include: How do microbes assemble with the world around them? How do plants play and have fun? How can fungi open evolution to stupidity? What function can cute behavior and appearance have for mammals? How do human hunter-gatherers use humor in their social dynamics and political organization? Each of the following chapters organizes the study of networked computing with organisms: early computer assembly with microbes; videogames and play with vegetation; networked websites and stupidity with fungi; social networking and cuteness with animals; forum discourse and humor with hunter-gatherer tribes. Before delving into these chapters, a note on reading order: The book can be read nonlinearly, jumping in at certain chapters and even particular parts attracting the reader. As an overall whole the book presents an account of the evolutionary development of becoming human. This development is itself non-linear, in the sense that it does not chart a progress from least to most advanced, rendering humans as the goal of development. Evolution is a process of variation and adaption, where forms of structure and behavior can be retained, released, refined, as well as regressed. As a species, humans have depended and still depend on the development of microbes, vegetation, fungi, and mammals. This book attempts to show human development as a process not of increasing efficiency, labor, intelligence, maturity, and seriousness. Becoming human is a diversion of these aspects, and if humans are the pinnacle of

evolution, it is as a species which tends toward playful, stupid, cute, and funny diversions.

Chapter Outline Chapter 2, “Microbe Computing,” examines how assemblage processes divert. The central understanding of assemblages is informed by the Deleuze-influenced philosophy of DeLanda. A word of warning: This chapter is the most complex and difficult read of the book. It diverts away from the playful, stupid, cute, and funny to instead develop the theoretical foundation. The focus of the chapter is on the under-studied computer programming of evolutionary processes by mathematician Nils Aall Barricelli (1950s), and John Conway’s well-known Game of Life (1970). From these programs the chapter develops a symbiotic notion of the relation between programmer and program, in which the human participant is not in complete control of the process. Perspectives on evolutionary programming are thereafter shown as instructive for understanding how populations of users influence technological development. The chapter concludes by considering how human attention is not distinctly separated into conscious agency, but has evolved in symbiosis with and distributed into technologies such as computing. Chapter 3, “Vegetative Games,” examines how play diverts. The central understanding of play—and its relation to games and fun—is formed here through analysis of Nintendo’s iconic game Super Mario Bros. from 1985. By connecting game studies with botany, the prospect of vegetative games is developed, which provides an understanding of how and what makes humans and non-humans play. The chapter reflects on vegetative decision-making, and how this takes the form of playful improvisation. Vegetative creativity is conceptualized as a dispersed form, which becomes rooted down into centralized systems of conscious thought in animals and human beings. Human play becomes a process of interacting with and redistributing cognition into other systems. Digital gameplay becomes fun by making us vegetate together with technological devices—to grow, metamorphose, and decay in programmed environments. Theorizing non-human forms of play opens also for the possibility of algorithmic fun. Chapter 4, “Worldwide Fungi,” examines how stupidity diverts. Networking is traced to an evolutionary lineage of assembling for problem-solving, stretching back to slime molds and fungal mycorrhiza. The chapter reconceptualizes the worldwide web into the worldwide

fungi. With intelligence characterized by efficiency in problem-solving, fungi is argued here as opening evolution to the immense differentiation potential of stupidity. Empirical material is analyzed to uncover how stupidity proliferates online, as ways of solving the problem of gaining attention. Populations browsing websites are shown to regularly follow clickbait directed to base desires, drawn to the secrets of good health and easy wealth, beauty, fame, and sexual promiscuity. The chapter tests what might be learned from such stupidity, in particular how clickbait reveals the potency of foolishness for a range of human social fields. This includes the technological development of artificial stupidity (rather than artificial intelligence), economic reliance on greater fools, art as abbreviation for artificial stupidity, and philosophy as a form of morosophy (a love of stupidity rather than knowledge). Chapter 5, “Social Petworks,” examines how cuteness diverts. Cuteness is rendered a process of retaining juvenile features and behavior into adulthood. The chapter analyzes some exceptionally famous social media profiles, including the Facebook celebrity dog Boo. Social networks are framed as social petworks, where users share animal selfies. This frame opens for exploring how technological development is predicated on and continues mammalian evolutionary processes, as technology is cutened and humans are domesticated to screen-bound living with algorithm-determined feeds. Cuteness comes with a range of creative potential, examined here through theorizing YouTube videos of birds parroting pop songs. Cuteness allows mammals to turn evolution from struggle to snuggle for survival, to increased investment into comforting and soothing distress. The intensity of this in contemporary social petworks is examined through care-giving of the disabled celebrity cat Lil Bub. The chapter concludes by offering a novel way of understanding what is known as cute aggression, a common yet paradoxical desire to squeeze or crush that which is perceived as cute without harmful intent. Chapter 6, “Human Tribes,” examines how humor diverts. Humor is rendered a social process, which has the potential for giving rise to as well as diverting ridiculous behavior. Analysis starts here with the 2016 election, where certain communities were invested in turning politics funny, and getting Donald Trump elected president as a joke. The chapter explores the different aspects of what made Trump funny, in particular in the production of Trump memes, and what allowed online discourse to

become politically influential. While Joe Biden’s victory could be considered a much-needed return to the normality of regular unfunny politics, the chapter considers how humor holds potential for leftist politics. The chapter asks the seemingly tautological question of what humans could teach us about human politics. The answer is found through reflections on tribalism in politics and a rethinking of the ideological position of paleoconservatism with perspectives from research on the actual politics of paleolithic tribes. Central here is the function of humor for tribal subversion of individual dominance. From tribal structures I develop a notion of truly funny politics, where ridicule is used to achieve and maintain collective egalitarianism. Chapter 7, “Becoming Humidity,” synthesizes an answer to the question of why diversions are so important for digital living today. I discuss what is indicated as the three main reasons. Firstly, I consider what it is about human cognition that might lead to diversions, bringing perspectives from cognitive neurology. Thereafter, I reflect on the ways in which diversions shape both organic and media evolution, offering a summary of findings. Finally, an epilogue brings an experimental attempt at thinking with diversions, considering what happens to theoretical reflections when they shift from the center of attention to themselves being turned into diversions.

Bibliography Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. 1944/1997. Dialectic of Enlightenment. London: Verso. Benjamin, Walter. 1935/2007. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, Trans. Harry Zohn, In Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt. Bogard, William. 2000. Distraction and Digital Culture. CTheory. Bridle, James. 2018. New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. London: Verso. Citton, Yves. 2017. The Ecology of Attention. Transl. Barnaby Norman. Malden, Ma: Polity Press. Crary, Jonathan. 1990. Techniques of the Observer. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DeLanda, Manuel. 1997/2000. A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. New York: Swerve Editions.

DeLanda, Manuel. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic. ———. 2011. Philosophy and Simulation: The Emergence of Synthetic Reason. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic. Deleuze, Gilles and Claire Parnet. 1988/2006. Dialogues II. London and New York: Continuum. Goldsmith, Kenneth. 2016. Wasting Time on the Internet. New York: Harper Perennial. Jagoda, Patrick. 2020. Experimental Games: Critique, Play and Design in the Age of Gamification. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Crossref] Johnston, John. 2008. The Allure of Machinic Life. Cybernetics, Artificial Life and the New AI. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Crossref] Kittler, Friedrich A. 1986/1999. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Berlin: Brinkmann & Bose. Lewis, Paul. 2017. ‘Our Minds can be Hijacked’: The Tech Insiders Who Fear a Smartphone Dystopia, The Guardian. October 6. https://www.theguardian.c om/ technology/2017/oct/05/smartphone-addiction-silicon-valley-dystopia. Accessed 14 Jan 2020. McLuhan, Marshall. 1962/2011. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. McLuhan, Marshall. 1964/2001. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. London: Routledge. Ngai, Sianne. 2012. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Parikka, Jussi. 2010. Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Plato. 2002. Phaedrus. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1960/2004. Critique of Dialectical Reason. London and New York: Verso Books. Simon, Herbert A. 1971. Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World. In Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest, ed. M. Greenberger. Baltimore: The

Johns Hopkins Press. Sloterdijk, Peter. 1987. Critique of Cynical Reason. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Srnicek, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA: Polity Press. Terranova, Tiziana. 2004. Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press. Williams, James. 2018. Stand out of our Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Crossref] Wolfe, Cary. 2009. What is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Wong, Julia Carrie Wong. 2017. “Former Facebook Executive: Social Media is Ripping Society Apart, The Guardian December 12. https://www.theguardian.c om/technology/ 2017/dec/11/facebook-former-executive-ripping-society-apart. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

Footnotes 1 Williams 2018.

2 Lewis 2017 and Wong 2017.

3 See for instance Terranova 2004; Srnicek 2017; Bridle 2018.

4 Simon 1971: 40–41.

5 Benjamin 1935.

6 Adorno and Horkheimer 1944/1997.

7 Crary 1990: 33.

8 Sartre 1960/2004: 257-258.

9 Bogard 2000.

10 Citton 2017: 5, 12.

11 Plato 2002: 71.

12 McLuhan 1964/2001: 28.

13 Benjamin 1935.

14 Kittler 1986/1999: 203.

15 Goldsmith 2016.

16 Ibid: 27.

17 Sloterdijk 1987: 104.

18 Deleuze and Parnet 1988/2006.

19 Jagoda 2020.

20 Ngai 2012.

21 DeLanda 1997/2000; 2006, 2011.

22 See for instance Wolfe 2009.

23 Stiegler 1994/1998, in Johnston 2008.

24 McLuhan 1962/2011; Kittler 1986/1999.

25 McLuhan 1962/2011; Kittler 1986/1999.

26 Parikka 2010: 10.

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022 A. Ervik, Becoming Human Amid Diversions https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13877-5_2

2. Microbe Computing Andreas Ervik1 (1) Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Andreas Ervik Email: [email protected]

Assembling With Programs Hello, world! The starting point for programming newbies is to write a program that prints this message. The computer does much of the work in order for this simple program to work. But, as astronomer Carl Sagan famously stated: “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”1 To form an initial understanding of how humans have come to coexist with computation, this chapter explores some examples of early computing. In this chapter I examine some early computing and how it grew out of cybernetics. Cybernetics is framed as an interdisciplinary approach to exploring the structure and capacities of systems, but I take issue with the notion of cybernetics as being in control and steering systems.2 This chapter considers the role of humans in the world instigated by computers through the framework of assembling. How do humans assemble with digital computers? The notion of assemblages comes from DeLanda’s philosophy, which is concerned with the ways processes and objects exist and exert influence, independently of what one may think and say about them.3 DeLanda has offered an account of development which does not privilege humans as actors, but discusses the influence of a range of things, from inorganic matter to the biomass of food and microbes, to linguistic forms.4 While humans may consider themselves to be in charge, as steersmen of technological progress, any development involves a range of different parts in assemblage.5 The concept comes from Deleuze, who defined assemblages as a multiplicity which is made up of many heterogeneous terms and which establishes liaisons, relations, between them, across ages, sexes and reigns—different natures. Thus, the assemblage’s only unity is that of a co-functioning: it is a symbiosis, a ‘sympathy’. It is never filiations which are important but alliances, alloys ...6 Sympathy, symbiosis, and co-functioning are ways of emphasizing processes of being informed by rather than being in control. Assemblages are exemplified with ecosystems rather than organisms, as in the words of DeLanda, “the relation between insects and the plants they pollinate … involves heterogeneous species interacting in

exteriority, and their relation is not necessary but only contingently obligatory, a relation that does not define the very identity of the symbionts.”7 The assemblages of computers likewise involve heterogenous parts of humans with hardware and software. Rather than in control, humans attend to the properties, tendencies, and capacities of a system.8 The term attending is used here to convey co-presence, coexisting with or tending toward. For instance, when attending to the assemblage that is a garden, some conditions are initiated by people; others are beyond control. And whereas attention has as its opposite in distraction, attending is a diversion of controlling, involving degrees of having and giving up control. Computer assemblages involve agency distributed into its parts. While the early pioneers of computing assembled with and attended to computers, they were stimulated by biology and the tendencies and capacities of organic systems. Wired magazine founder Kevin Kelly has stated that “biology was ported to computers just as they were born.”9 The porting includes engaging with and modeling machines and programs on organisms, ecosystems, and evolutionary processes. Examples include W. Ross Ashby’s self-organizing homeostat and the navigating and maze-solving robot mouse of Claude Shannon and robot tortoise of W. Grey Walter, as well as John von Neumann’s theory of selfreproducing automata and Barricelli’s programming of such automata.10 Barricelli’s program was among the very first pieces of software written for one of the earliest programmable pieces of computer hardware, and it attempted to instigate digital evolution. In this chapter I will examine the porting of biology. This involves not simply transferring knowledge produced in biology to media. It requires an openness to novel and potentially unexpected sharing of structuring parameters. Analyzing empirical material and synthesizing knowledge from a range of disciplines, the goal here is to understand the structure of what might otherwise appear as accidental and unpredictable consequences of development. Testing boundaries, convergences, and possibilities, I will infuse computing and network with a range of organisms and organic structures, drawing from the development, relations, and behavior of organisms in fields of evolution, ecology, and ethology.

I will be focusing on the work by Barricelli, who despite a certain resurgence of interest in computational evolution has remained relatively obscure. Secondly, I focus on another piece of evolutionary programming, The Game of Life (hereafter simply Life). This program holds a particular position in DeLanda’s philosophy, where computer modeling provides perspectives on physical, chemical, and organic development.11 Both programs are discussed in order to explicate aspects of evolution theory which will be foundational for the work in the following chapters. Most fundamentally, I am concerned with modeling networked computing in order to understand the properties and dispositions of diversions, and the potential for examining development across different origins and materials. The next section analyzes Barricelli’s evolutionary programming. His programing could be considered a precursor for studies in artificial life.12 Yet, the questions raised by Barricelli were not whether digital computing could generate artificial forms of life. He aimed to test whether processes of selection and mutation could instigate evolution, and what role symbiosis could have in this process.13 This necessitates forming an understanding of symbiosis, with its impact on the forming of organisms, species, and ecosystems. I consider how the structural organization of organic systems is comparable to that produced in programming. Furthermore, I discuss the relation between programs and humans: How could the symbiosis inform our understanding of their relation? Thereafter, I continue to Life, which was first presented in a monthly column on recreational logic puzzles in Scientific American. Life was introduced by Martin Gardner, who claimed that because of its “analogies with the rise, fall, and alterations of a society of living organisms, it belongs to a growing class of what are called ’simulation games’—games that resemble real-life processes.”14 Life would turn into an extremely popular pastime, and it is currently available online for anyone to tinker with. I examine Life precisely because it has been dispersed broader than Barricelli’s mostly forgotten programming. This dissemination has allowed for richer knowledge produced about the dynamics of the program. I will use this knowledge to discuss how complexity emerges, is sustained, and is varied in the program. In his theory of evolution, Darwin distinguished between natural and artificial selection. Is

computer programming of evolution closer to artificial or natural selection? Lastly, the chapter turns to the development of computation, to consider not simply evolution within programs, but the evolution forming from the meeting with populations of users. How did computation turn from select individuals investing themselves into a field of lasting importance for large populations? An obstacle for considering technological development as evolution seems to be the purpose and function technology has for humans. From Barricelli and Conway’s program I will uncover key structuring tendencies which will complicate the possibility of ascribing computational change entirely to human decisions. Computer development will be argued to form out of unintentional consequences and evolutionary pressure.

Symbiotic Programming What is life? The word “life” makes us think of natural beings, organisms. Life designates beings sharing common chemical building blocks. All known life forms are carbon-based, but is this substrate an obligatory or simply a contingent factor of known life forms? In strong theories of artificial life, computer programming not only produces models of, but should be seen as generating, life in another material basis.15 Do computers generate artificial life forms? Prior to the theory of evolution, the question of life could be considered a metaphysical inquiry, concerning the fundamental nature of the world and its entities. Life was an essence of organisms—that which makes them fundamentally what they are. The living can be understood as alive because it belongs to the category of life, whereas something non-living does not and thereby cannot. Darwin’s theory showed the relatedness of organisms not as categorical belonging, but as formed through historical processes. Philosopher Eric Schliesser frames Darwin as among the first synthetic philosophers, bringing “together insights from a whole number of distinct sciences (geology, botany, paleontology, morphology, entomology, animal husbandry, climate science, etc.) and, in turn, self-consciously revolutionized them with his ideas and opening up new avenues for scientific research.”16 From geology, Darwin took the expansion of the timescale of our planet, the changing of landmass, and the excavation of fossils. Economics provided the theory with the impetus for change, in the form of resource scarcity and abundance. Darwin turned biology into a discipline of examining how organisms and species evolve over time. The theory of evolution renders organisms and species as processes as much as beings. With DeLanda the stability of an object becomes determined by timescale: “at the level of geological time scales, in which a significant event such as the clash between two tectonic plates may take millions of years, an entire human life becomes a bleep on the radar screen—that is almost instantaneous event.”17 The process of becoming and the state of being are not categorically distinct, but temporally distinct. DeLanda uses the notion of individuation to describe the processual nature of organisms, but “once the process yields fixed extensities and qualities, the latter hide the intensities, making

individuation invisible and presenting us with an objective illusion, the same illusion that tempts us to classify the final product by a list of spatial and qualitative properties, a list which, when reified, generates an essence.”18 Rather than fixed essences, organisms and species are defined by processes of individuation. Evolution has been considered a process where environmental pressure leads to the best result, after which change ceases. But this conception of evolution has been replaced with one lacking a fixed endpoint, and thus the potential for change remains part of any current stable state.19 Until Darwin, the regularity of a species could be regarded as conveniences based on visual resemblance, with arbitrary relation to the fluctuating forms they described.20 With evolution theory, species were reconceptualized. As philosopher Elizabeth Grosz writes, they “transform[ed] a difference in kind into a difference of degree.”21 DeLanda notes how evolution theory turned species into “piecemeal historical constructions, slow accumulations of adaptive traits cemented together via reproductive isolation.”22 Speciation results from sexually reproducing organisms becoming isolated and, over time, becoming incapable of propagating or of giving birth to sexually reproductive offspring. Species thereby likely first emerged with sexual differentiation in microbes. Rather than the question of what life is and whether systems could generate artificial life, Darwin’s theory paved the way for understanding species and organisms as processes. Furthermore, it opened for the possibility of producing these processes in other material substances than organic ones. The connection between organisms and technologies was noticed by Darwin’s contemporary, the author Samuel Butler. He proposed that were arrangements of intricate mechanisms: If, then, men were not really alive after all, but were only machines of so complicated a make that it was less trouble to us to cut the difficulty and say that the kind of mechanism was ‘being alive’, why should not machines ultimately become as complicated as we are, or at any rate complicated enough to be called living, and to be indeed as living as it was in the nature of anything at all to be?23

Cyberneticians would later attempt to actualize Butler’s notion.24 W. Ross Ashby identified a historical lack of machines of what could be termed “medium complexity,” as systems had either been simple mechanisms like watches and pendulums with “few and trivial properties” or they were animals, with “properties so rich and remarkable that we have thought them supernatural.”25 Among the early pioneers of digital computing, and a contributor to the first nuclear bomb, the Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann worked also to produce machines of medium complexity, capable of dynamic and unpredictable behavior. While calculating for the production of the first nuclear bomb, von Neumann was theorizing digital organisms. He proposed using the regularities of organic organization to construct what he termed “self-operating machines” or “automata.” With mathematician Stephen Wolfram automata is defined as “mathematical idealizations of physical systems in which space and time are discrete, and physical quantities take on a finite set of discrete values.”26 Such automata are “black-boxed,” in that their inner structure need not be disclosed, but are in the words of von Neumann, “assumed to react to certain unambiguously defined stimuli, by certain unambiguously defined responses.”27 I find it important here to distinguish between programming “artificial life” and programming digital organisms. In DeLanda’s philosophy, categorically opposed terms such as living and non-living, and nature and technology, are reified generalities—theoretical constructs for which no account of actual assembly could be given.28 In DeLanda’s philosophy, regularities are not ascribed to things by categorical belonging—what makes an organism an organism is not their essential belonging to the category of life. Instead, any material, thing, or being is considered as unique, actualized individuals, whose regularities are provided by what is conceptualized as “the virtual.” These regularities can cross what is perceived and conceptualized into categorical divides. DeLanda renders reality as “populated by virtual problems,” which are actualized as “a divergent set of actual solutions to those problems.”29 The actual form something takes is determined by the problems it responds to. While the actual is made up of distinct forms that may be categorically opposed, virtual problems may be shared across domains. The notion of actual and virtual thus allows for

theorizing dynamics shared across media and organic evolution, without postulating a collapse of distinctions between nature and man-made technologies. The question is thereby not whether programmed evolution instigates a passing of categorical thresholds from non-living to living, but simply whether it accurately parallels the dynamics of organic evolution. Shared parameters in digital and organic evolution become not a product of more or less convincing metaphors, but of successful computational synthesis of system dynamics.30 Media scholar, N. Katherine Hayles, has stated that “computational media have a distinctive advantage over every other technology ever invented … because they have a stronger evolutionary potential than any other technology.”31 Hayles ascribes this evolutionary potential to computing making possible the simulation of other systems. How does the evolutionary potential of computers function, and how do computers simulate organic systems? Having constructed one of the first computers, at Princeton University’s prestigious Institute for Advanced Study, von Neumann invited Barricelli to use it for an experiment with automata.32 Barricelli saw evolution as a process of “spectacular simplicity,” considering that it holds the characteristics of a “purely statistical phenomenon,” and would attempt to produce it computationally.33 Beginning in the early 1950s, he would conceptualize, program, and successfully run what is likely the first experimental evolutionary computer programs. The results were published in Italian in 1954, with English translations following three years later. Barricelli created his ecosystem of one-dimensional cellular automata, through working in binary machine instruction code (see Fig. 2.1). The ecosystem was made up of a horizontal row of 512 arrays, each consisting of a number from -18 to 18 (termed genes), or no number (no gene). The first row acted as starting condition, followed by successive generations in rows below. The initial conditions were selected by randomized number generation. The automata were then exposed to a set of rules for mutation and reproduction—termed “norms.”34 Running this program on the Institute for Advanced Study’s computer, the process was allowed to unfold over 5000 generations. Barricelli made notes on how the running program would produce patterns, which could maintain coherence over successive generations. He would name such enduring

forms “numerical symbioorganisms,” but cautioned that these patterns were not to be mistaken for organisms. The terminology was intended as mathematical, with terms from biology as analogies with biological concepts.35 Barricelli describes the process required to give rise to evolution: Make life difficult but not impossible for a simbioorganism [sic], let the difficulties be various and serious but not too serious; let the conditions be changing frequently but not too radically and not in the whole universe at the same time; then you may see an evolution transforming the symbioorganism with a surprising rapidity and creating properties and organs which will make the symbioorganism able to face all the difficulties and all the new situations it meets. But do not expect to observe an evolution process if you let the symbioorganism vegetate in peace and safety in a perfectly homogenious [sic] universe. In that case you will probably observe nothing essentially more complicated than the simplest molecule.36

Fig. 2.1 Screenshots from Barricelli’s digital ecosystem of symbioorganisms, reprogrammed and described by Alexander Galloway: “Each swatch of textured color within the image indicates a different bionumeric organism. Borders between color fields mean that an organism has perished, been borne, mutated, or otherwise evolved into something new”

Both in identifying “numerical symbioorganisms” and in setting the difficulty right for evolution (not too safe, but not too challenging; neither too few nor too frequent changes), Barricelli seems to impact the program. What is his role? Are the numerical organisms produced by the program as it runs, or are they imposed—through interpretation or

through programming—by Barricelli? It is possible to consider Barricelli as a “no-player,” who determines the position and number of “numerical genes,” which are then subject to the rule set, with the rule set subsequently generating interactions between these genes, causing the formation of numerical organisms.37 As a no-player, the person could be replaced with a mechanism providing randomized starting conditions, and perhaps also randomly varying the rule set—which was indeed part of Barricelli’s method. In diametrical opposition to such a no-player view, the entire evolution and the forming of “numerical organisms” could be ascribed to Barricelli. The distinction between the perspectives above and the questions that they raise is better understood with references to the shift from what is referred to as first-order to second-order cybernetics. First-order cybernetics (among others Norbert Wiener, W. Grey Walter, von Neumann, Ashby, and Barricelli) were concerned fundamentally with understanding and replicating system dynamics. Second-order cybernetics (Gregory Bateson, Stafford Beer, Gordon Pask, and von Foerster) situates what is regularly referred to as “the observer”—but should perhaps be considered an “interactor”—as part of the system dynamics. In his historical account of cybernetics, Andrew Pickering considers this shift as a broader change from concerns of ontology (knowing how things are) to epistemology (knowing how we know how things are): I take the cybernetic emphasis on epistemology to be a symptom of the dominance of specifically epistemological inquiry in philosophy of science in the second half of the twentieth century, associated with the so-called linguistic turn in the humanities and social sciences, a dualist insistence that while we have access to our own words, language, and representations, we have no access to things in themselves. Cybernetics thus grew up in a world where epistemology was the thing, and ontology talk was verboten.38 Pickering here connects second-order cybernetics to an account of knowledge in which humans cannot know anything beyond our own discourse. As philosopher of science Roy Bhaskar has argued, such an account constitutes an epistemic fallacy, as the question of what there is

becomes conflated with questions of access to reality.39 The question of what is known becomes indistinguishable from the question of how we can know. If the behavior of the patterns in Barricelli’s program were reduced to the programmer one would be committing this fallacy. At the same time, second-order cybernetics’ insistence on including the interactor as part of the system is not without merit for understanding what is going on in Barricelli’s programs. As opposed to the dichotomy of focusing on either an “observed system” or an “observer of a system,” however, Barricelli offers a way to include the interactor without reducing system dynamics to human understanding. This perspective is not made explicit in his writings. It is instead developed here from his programming, the theoretical work underpinning it, as well as later theorizations of computer evolution. Pioneer of digital dynamic behavior Christopher Langton emphasizes how automata produce results which are independent of its programmers: “The constituent parts of the artificial systems are different kinds of things from their natural counterparts, but the emergent behaviors that they support are the same kinds of thing as their natural counterparts: genuine morphogenesis and differentiation.”40 Morphogenesis means structure forming, and the programming is argued to give rise to emergent or second-order structures. This entails structures not contained in the rule set, which result from interactions between automata. The simple and rulegoverned objects interact, and form something not entirely determined by the rules of the program. Another pioneer of evolutionary computing, John Holland, uses the term complex adaptive systems, which are not “a simple sum of the behavior of its parts,” but produce “aggregate behavior” which “often feeds back to the individual parts, modifying their behavior.”41 While determined by the rule set, the emergent patterns are unpredictable, as computer historian John Johnston writes in his account of cybernetics: “[T]he changing variables … are now influencing one another in such a tangle of nonlinear feedback circuits that there is no way to compute the outcome in real time.”42 DeLanda details how structures are emergent when they “have properties, tendencies, and capacities that are not present in the individual automata.”43 While the initial properties are determined by the rule set, the states and dispositions that emerge from interactions cannot be fully

accounted by or ascribed to the programmer. The program must run in order for the researcher to gain knowledge of what kind of emergent structures emerge. In Barricelli’s program, free-flowing “numerical genes” would form into larger patterns, termed “numerical symbioorganisms.” These displayed behavior which rendered their coherent structures as emergent, more than observations and distinctions made by the researcher. In particular the structures would attempt to maintain their own coherence. Barricelli describes a process of him randomly cancelling elements, which would lead the stable structures of numerical organisms into a mode of self-repairing this damage.44 This repairing echoes a central framework for understanding organisms first introduced by physicist Schrö dinger in 1944. Schrö dinger frames entropy, the tendency of order to break down over time, as a central problem for organisms. The systematical arrangement in organisms—of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen—demonstrates an (at least temporary) avoidance of entropy. Organisms “keep going”—they maintain energy exchange with environments longer than other entities. While most systems reach a standstill quite quickly, living entities take their time. As the entropy of organisms increases, they approach states of maximum entropy (death). To avoid (or rather, postpone) death, organisms “draw negative entropy from their environment, by eating, drinking, breathing and ... assimilating.”45 Organisms live in an environment tending toward disorder, and maintain their own organization by increasing external entropy. Following from the entropic understanding of organisms, the aforementioned cybernetician Ashby formulated a machinic notion of organisms as self-organizing systems, which “demonstrate a self-induced change of organization.”46 Biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela developed this into the concept of autopoietic machines, which “subordinate all changes to the maintenance of their own organization, independently of how profoundly they may otherwise be transformed in the process.”47 In a more recent account of how organic systems organize, geologist Eric Schneider, writing together with Dorion Sagan, shifts the understanding from individual organisms self-structuring to organisms forming as responses to external gradients.48 Gradients are defined as differences across distance, including differences of pressure,