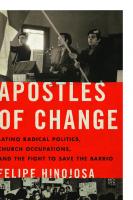

Apostles of Change: Latino Radical Politics, Church Occupations, and the Fight to Save the Barrio 9781477322000

In the late 1960s, the American city found itself in steep decline. An urban crisis fueled by federal policy wreaked des

167 51 5MB

English Pages 237 [239] Year 2021

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

Apostles of Change

Historia USA A series edited by Luis Alvarez, Carlos Blanton, and Lorrin Thomas

Books in the series: Perla M. Guerrero, Nuevo South: Latinas/os, Asians, and the Remaking of Place Cristina Salinas, Managed Migrations: Growers, Farmworkers, and Border Enforcement in the Twentieth Century Patricia Silver, Sunbelt Diaspora: Race, Class, and Latino Politics in Puerto Rican Orlando

« Felipe Hinojosa »

Apostles of Change

Latino Radical Politics, Church Occupations, and the Fight to Save the Barrio

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright © 2021 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2021 “Armitage Street,” by David Hernandez, copyright © 1994 by David Hernandez; from Unsettling America: An Anthology of Contemporary Multicultural Poetry, edited by Maria Mazziotti Gillan and Jennifer Gillan. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713-7819 utpress.utexas.edu/rp-form The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Libr ary of Congr ess Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hinojosa, Felipe, 1977- author. Title: Apostles of change : Latino radical politics, church occupations, and the fight to save the barrio / Felipe Hinojosa. Other titles: Historia USA. Description: First edition. | Austin : University of Texas Press, 2021. | Series: Historia USA | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020027902 ISBN 978-1-4773-2198-0 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4773-2200-0 (library ebook) ISBN 978-1-4773-2201-7 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Radicalism—United States—Religious aspects— Christianity—History—20th century. | Hispanic Americans—Political activity—United States—History—20th century. | Protest camps— United States—History—20th century. | Church buildings—Secular use—United States—History—20th century. | Church and social problems—United States—History—20th century. | Urban renewal— Social aspects—United States—History—20th century. | Christianity and politics—United States—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HN49.R33 H55 2021 | DDC 303.48/4—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020027902 doi:10.7560/321980

For my students at Texas A&M University whose courage over the years has inspired and lifted our campus. And for my students at Emory University, who during the 2018 spring semester made history by proclaiming loudly, for everyone to hear, that consciousness is power.

Contents

Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Abbreviations

xv

Introduction. The People’s Church

1

Chapter One. Thunder in Chicago’s Lincoln Park

19

Chapter Two. “People—Yes, Cathedrals—No!” in Los Angeles Chapter Thr ee. The People’s Church in East Harlem

89

Chapter Four. Magic in Houston’s Northside Barrio

120

Conclusion. When History Dreams

Notes 161 Bibliography Index 207

195

146

56

Preface

T

he journey toward writing this book began in Chicago on the day that my good friend and fellow historian Lilia Fernández introduced me to her city. I saw Chicago through the eyes of a historian who knew the stories, the neighborhoods, and where the Armitage Methodist Church had once stood in Lincoln Park. The church is now gone, replaced by a Walgreens store. On that day some years ago, I knew that I wanted to tell the story of that church and others like it. It is a story that begins in the urban north, in the frigid midwestern city of Chicago, where Latina/o radicals first occupied a church. I did not grow up in Chicago or in any of the cities that I cover in this book, but I did grow up surrounded by churches, preachers, and activists in South Texas. This story is close and personal to me. My father was a minister, and from the time I was in junior high school, we lived in a house behind the church. Summers were spent visiting other churches on both sides of the Texas/Mexico border and across the Great Plains and the Midwest. We began every road trip, meal, and football game with a prayer. I was taught that serving people, seeking justice, and showing mercy were all necessary to live a life of faith. While I grew up as an evangélico, far from the ubiquity of Catholicism, my experience was nonetheless typical for most Mexican Americans in South Texas. Religion is central to Latina/os living in the United States: from festivals to church revivals, from altars honoring the dead to church or mass every Sunday, sometimes even more. Our knowledge of religion often comes from our upbringing, from our social experiences with God—good, bad, or nonexistent. We learn of the limits, or attempts to impose limits, inherent in religious institutions. The experience is so deep, so connected to our sense of self, our very identities, that we are of-

«x»

Pr eface

ten expected to discard or discount our affinities with the supernatural capabilities of faith in order to free ourselves from the trauma involved in institutional religion, from colonialism to sexual abuse. This is at least part of the reason that studies on spirituality—on spiritual mestizaje, as Gloria Anzaldúa called it—tend to be more prominent within the field of Latina/o studies.1 These studies focus on the noninstitutional, non-Western, and non-Christian forms of faith that have sustained oppressed peoples across time and space. So I am keenly aware that to write about religion and the institutional church, as I do here, resurrects the trauma that is often associated with the institutional church. The Christian church in the United States is distant, cold, European, and rarely on the side of human liberation. The institutional Christian church is about boundaries and limits, do’s and don’ts. But my work here is neither to sidestep the disruption and chaos that religious trauma has created nor to give power and agency to religious institutions that have only hindered our opportunities. Churches can be liberative spaces, but they can also be oppressive cages for those of us who support a freedom politics open to all: LGBTQ, black, brown, undocumented, and poor. In the following chapters, I tell stories of the struggle to wholly transform the sacred space of the church, to move it into an embrace with its community, and to liberate it from its own strictures.2 I am interested in showing how we can reimagine the Chicana/o and Puerto Rican freedom movements, how we can focus on their specificities even as we draft a narrative of Latina/o activism during the late 1960s and 1970s. As the essayist Lewis Hyde argues, this work requires enacting a “subversive genealogy,” one that forgets the idealism of a single-origin story and instead remembers the thousands of small moments that made the movement in barrios, fields, factories, and churches and on the migrant trail—in those corners heretofore unexamined.3 We have many single-origin stories that we tell ourselves and tell our students: school walkouts, Los Cinco in Crystal City, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta in Delano, a “garbage offensive” in East Harlem. Keeping our idealism focused on single-origin narratives thwarts our imagination and limits the possibilities, visions, and politics of the thousands of small moments that gave birth to the Latina/o freedom movement. In these pages I hope to reveal those small but politically vibrant moments that made up the Latina/o struggle for freedom.

Acknowledgments

T

his book is for the students: the Dreamers, radicals, artists, and liberal arts and STEM majors who have marched, petitioned university presidents, and called out racist oppression. Your commitment to the struggle—to the work against oppression and for justice—is a beautiful testament to the love you have for building a university where all students rise together. Working on this book gave me the opportunity to be in the presence of some incredible people: activists, mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and grandfathers all sat with me to teach me about the moments when they changed the world. I sat with them at their kitchen tables and in their living rooms, in restaurants with loud music, and in quiet coffee shops where we were the loudest people in the room. I am thankful for the time they gave me, for the stories they shared with me, and for the grace they granted me as I stumbled my way through this project. Apostles of Change is a labor of love. And none of it would have been possible without the beautiful people who walked with me every step of the way—the people who provided critical feedback, encouraged me in moments of exhaustion, and believed in me in those moments when I did not believe in myself. I am thankful for each and every one of you. I started my research with assistance from a number of organizations and intellectual communities. The Melbern G. Glasscock Center for Humanities Research at Texas A&M University provided the coins that paid the research tolls. Special thanks to Dr. Emily Brady (director of the Glasscock Center) and Amanda N. Dusek (Glasscock Center program coordinator) for their unwavering support of this project. An Arts & Humanities Fellowship from the Division of Research at Texas A&M

« xii »

Ack nowledgments

University assisted me in finishing the project and introduced me to the brilliant research being done across the university. But it was my time at the James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, that changed everything. During that year, I worked, laughed, shared delicious meals, and made community with a distinguished group of scholars: Ashley Brown, Derek Handley, Justin Hosbey, Taina Figueroa, Alexandria Lockett, Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Alison Parker, Ashanté Reese, Kyera Singleton, Charissa Threat, Kali-Ahset Amen, Javier VillaFlores, Gary Laderman, and Andra Gillespie, the director of the program. And a big thank you to my roommate, Greg Wickersham, for being such a gracious host and introducing me to the beautiful city of Atlanta. My experience teaching at Emory University also introduced me to smart and accomplished students. Teresa Apel Posadas and Jonathan Peraza—both gifted scholars and community leaders—provided key research assistance for this book as well as great conversations about the limits and possibilities of Latina/o politics and activism. Thank you so much, Teresa and Jonathan. Writing this book took me to several archives across the country. In each place, I met incredible librarians and archivists who made my job so much easier. Special thanks to the good people at the United Methodist Archives and History Center at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey; the University of Illinois at Chicago Archives; the Rockefeller Research Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York; and the New York Public Library. I will forever be grateful to archivists who helped me gain permission for the amazing photos in this book. Thank you, Allison Davis, at the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia; Brittan Nannenga, at DePaul University in Chicago; Matt Richardson and Mikaela Selley, at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center; Xaviera Flores, at the University of California–Los Angeles Chicano Studies Research Center; Calli Force, at the Special Research Collections at University of California–Santa Barbara; and Roisin Davis, at Haymarket Books. Special thanks also to the three amazing photographers with whom I had the privilege of working and whose photos are included in this book: Luis Garza (Los Angeles), Carlos Flores (Chicago), and Hiram Maristany (New York). I am also grateful to Samantha Rodríguez for sharing her deep knowledge of Chicana/o activism in Houston and for connecting me with activists from that era. Thank you so much, Samantha. And I’ll never forget that magical afternoon I spent in the faculty lounge at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. There I sat, going through

Ack nowledgments

« xiii »

three large boxes that Professor Ken Sawyer had collected as part of his work with the Young Lords in Chicago, as faculty members came in and out for coffee. What a moment! Thank you, Ken. Tim Matovina, Lilia Fernández, Johanna Fernández, Rudy Guevarra Jr., Samantha Rodríguez, Roberto Treviño, Jimmy Patiño, and Jorge J. Rodríguez V. all read drafts of the manuscript. Each of these scholars well understood my passion for this project and helped me refi ne my ideas and clarify my points. My good friend Carlos Blanton believed in this project back when it was just a tiny idea in my head. And I have always appreciated Carlos’s willingness and readiness to talk politics, sports, religion, the writing process, and Chicana/o history in general. Thank you for being such a great colleague and mentor, Carlos. I also want to thank Luis Alvarez and Lorrin Thomas (who together with Carlos serve as coeditors of the Historia USA series for University of Texas Press) for believing so strongly in this project and my sponsoring editor at UT press, Kerry Webb, with whom I have enjoyed working on every aspect of this project. I’m thankful to Johanna Fernández, Darrel Wanzer-Serrano, and Jorge J. Rodríguez V., who each provided key insights into the Young Lords and helped guide me and introduce me to the multiple worlds of the Young Lords in New York City. Mario T. García, Anne Martínez, and Rosie Bermudez have on multiple occasions helped me think through ideas about this project, helped with source material, and copresented with me on a number of conference panels over the years. And many thanks to Jaime Pensado, who helped me to better understand Catholic youth activism in Latin America in the late 1950s and its connections to religion and radical politics in the United States. Mil gracias, Jaime. I would not have made it this far without the strength provided to me by the friendships, the brotherhoods and sisterhoods, and the spaces where we meet to lift each other up as we do this work. It is impossible to name everyone here, but I will just say that I am blessed to know so many incredible people who everyday are teaching, writing, and marching to build a better world. My wonderful colleagues at Texas A&M have provided so much support over the years: Al Broussard, Carlos Blanton, Sonia Hernández, Sarah McNamara, Armando Alonzo, Angela Hudson, Brian Rouleau, Dan Schwartz, Side Emre, Evan Haefeli, April Hatfield, David Vaught, Hoi-eun Kim, Andrew Kirkendall, Jason Parker, Stephen Riegg, Olga Dror, Rebecca Schloss, Terry Anderson, Kate Unterman, Erin Wood, Kelly Cook, and Mary Johnson. And I am not sure where I would be without my wonderful colleagues in Latina/o studies, who con-

« xiv »

Ack nowledgments

stantly work to make Texas A&M University a welcoming place for all students: Nancy Plankey-Videla, Pat Rubio-Goldsmith, Sergio Lemus, Regina Mills, Marcela Fuentes, Gregory F. Pappas, Luz Herrera, and Cruz Ríos. I admire each of you so much. And a shout-out to the amazing current and former graduate students with whom I’ve had the privilege of working in the history department: Laura Oviedo, Tiffany González, David Cameron, Daniel Bare, and Manny Grajales. Over the years I have been blessed to be surrounded by wise, smart, and compassionate scholars who inspire me: Raúl Ramos, Natalie Garza, Trini Gonzales, Jesse Esparza, Juan Galván, Carlos Cantú, Anne Martínez, Kristy Nabhan-Warren, Sergio González, Maggie Elmore, Sujey Vega, Lloyd Barba, Lauren Araiza, Gordon Mantler, Lori Flores, Delia Fernández, Omar Valerio-Jiménez, Christian Paiz, Ernesto Chávez, Sandra Enríquez, Mario Sifuentez, Eladio Bobadilla, Yuridia Ramírez, Gustavo Licón, Deborah Kanter, Max Krochmal, John Mckiernan-González, Cary Cordova, Tobin Miller Shearer, Regina Shands Stoltzfus, Jerome Dotson, Tyina Steptoe, Adriana Pilar Nieto, Eric Barreto, and James Logan. I admire all of you for who you are, for the work you do, and for the grace you show to those around you. And much love to Rudy Guevarra Jr. and Michelle Téllez, who make me laugh, inspire me to do good work, and remind me to stay grounded and committed to the people and places I love. Shout-outs to Jimmy Patiño, Johanna Fernández, and José Alamillo, whose commitment to radical scholarship and community building brings out the best in all of us. And I cannot forget Glenn Chambers, whose friendship and mentorship saved me when I first arrived at Texas A&M. I’m not sure I, or for that matter my family, would have made it without the love we received from both Glenn and Terah Chambers during those first few years in College Station. As always, I am grateful to my beautiful family. Words are not enough. Simply put, none of me and none of my work would be possible without my life partner, Maribel Ramírez Hinojosa. Te amo, mi amor. And my babies are now teenagers: Samuel Alejandro and Ariana Saraí. You are my vision, my hope, and the reason why I continue to believe, and will always believe, that a world where justice and love reign is indeed possible. May you always believe in the power that is inside of you.

Abbreviations

ACTOR

Action Committee to Oppose Racism

BPP

Black Panther Party

CORE

Congress of Racial Equality

CPLR

Católicos Por La Raza

FBI

Federal Bureau of Investigation

FSUMC

First Spanish United Methodist Church

HAI

Hispanic-American Institute

IAF

Industrial Arts Foundation

IFCO

Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization

IWW

Industrial Workers of the World

LACC

Los Angeles Community College

LADO

Latin American Defense Organization

LPCA

Lincoln Park Conservation Association

LULAC

League of United Latin American Citizens

MARCHA

Methodists Associated Representing the Cause of Hispanic Americans

MAYO

Mexican American Youth Organization

MEChA

Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán

MTS

McCormick Theological Seminary

NCC

National Council of Churches

NRSV

New Revised Standard Version

NSCM

Northside Cooperative Ministry

« xvi »

Abbr eviations

PADRES

Padres Asociados para Derechos Religiosos, Educativos y Sociales

PASO

Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations

PLAC

Presbyterian Latin American Caucus

PPC

Poor People’s Coalition

PSP

Puerto Rican Socialist Party

RGS

Real Great Society

RUA

Rising Up Angry

SAC

Sociedad Albizu Campos

SDS

Students for a Democratic Society

SNCC

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

SOHAM

Section of Hispanic-American Ministries

UCC

United Church of Christ

UFW

United Farm Workers

UFWOC

United Farm Workers Organizing Committee

UMAS

United Mexican American Students

UNO

United Neighborhood Organization

UPCUSA

United Presbyterian Church in the USA

USCC

Urban Task Force of the US Catholic Church

UUSC

Unitarian Universalist Service Committee

VISTA

Volunteers in Service to America

YLO

Young Lords Organization

Apostles of Change

Introduction

The People’s Church

A cry for greater economic justice rises today from a million lips. Sometimes this cry falls into a murmur. In other occasions it reaches a thunder pitch, like in Cesar Chavez and “La Raza Unida” movements. But it can all be heard today across the nation: from Delano, California, to Division Street in Chicago; from the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, to Spanish Harlem in New York. National Cou ncil of Churches, 19701

I

n late 1969 leaders from the Armitage Methodist Church in Chicago gathered to draft a theological statement. In preceding months the church had become embroiled in a public fight against urban renewal. Its building had been occupied by the Puerto Rican revolutionary Young Lords Organization (YLO), and its pastors— the Reverend Bruce and Eugenia Johnson—had been brutally murdered, stabbed to death by assailants in their home. The case remains unsolved. Shaken by the loss and preparing for the fights ahead, church leaders drafted this statement: As a church, we understand ourselves to be a people with a history. . . . We see that the process of urban renewal is directed by a few who oppress the majority for the sake of their own political and economic interest. Specifically we see the poor, especially the black and Spanishspeaking poor, are denied access to economic independence and security. As a church we are aware of the limits and possibilities in our community. . . . It is then with this Trinitarian understanding of life

«2»

Apostles of Change

and our particular situation that we dare to be the church in Lincoln Park—in the midst of the limits and possibilities being forced to decide on behalf of all men to embrace the mission for the sake of humanness.2

The statement, which came from a largely white and liberal congregation, signaled the church’s public partnership in a grassroots movement to dream of new housing and community possibilities for a neighborhood on the brink. In Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, the dream was housing by and for poor people.3 It was a powerful message made even more urgent by the politics that engulfed it. When the members of Armitage Methodist Church penned these words, Chicago was a city reeling from its urban renewal binge, the assassinations of several radical activists, and a progressive religious community on the verge of being dismantled. The city that was once considered the center of liberal Christianity saw its foundations rocked by a new wave of Black and Brown Power activism—bold, imaginative, anticapitalist, and antiimperialist—not impressed with the church’s verbal commitments to the struggles of poor people. To make their point, Latina/o radicals started occupying and disrupting church services in 1969. First in Chicago and later in Los Angeles, New York City, and Houston, these young radicals transformed churches into staging grounds to protest urban renewal, poverty, police brutality, and antiblack and anti-Latina/o racism.4 Choosing to occupy churches was not a random act. Latina/o radicals were out to make a point about the symbolism and power of the church in neighborhoods across the country.5 In the process, they set in motion a transformative project that temporarily reconstructed the meaning of the church as a tactical act of resistance—they introduced us to a new church, the “People’s Church.” In each of the four cities covered in this book (Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and Houston), activists not only changed the name of the church or made bold statements like “People—Yes, Cathedrals—No!” (Católicos Por La Raza in Los Angeles). They envisioned a space where the social needs of the community could be met, where Sunday school rooms could be transformed into doctors’ offices and the church kitchen could be used to feed breakfast to kids before school. This program guaranteed that the church— the very building itself—was anything but neutral and was instead part of the larger project to push back against urban renewal, to push back against the feeling of displacement. In every conceivable way, they believed that another church was possibile.6 These occupations and disruptions, their context in the midst of an

Introduction

«3»

urban crisis, the tensions they created, and the worlds they imagined make up the central subjects of this book. In 1969 churches became strategic sites, indeed sacred spaces, where radical groups staged their movements and proclaimed their message of community control and power to the world.7 The occupations and disruptions took place against the backdrop of Black and Brown Power movements in the late 1960s that shifted civil rights rhetoric toward a class-oriented, revolutionary nationalism that challenged economic inequality and white supremacy. It was a moment when, as historian Carlos Blanton argued, radical ethnic politics “eroded a basic underlying premise of twentieth century liberalism: pluralistic politics in which ideology and national interest subsumed ethnicity.”8 By the late 1960s it was abundantly clear that the promises of liberalism—the hope that working within the system was the best way to change the system—had fallen flat. Nowhere was this clearer than in the American city, where the urban crisis had wrought despair, destruction, and displacement for poor and working families. The American city, which for much of the twentieth century and especially in the years after World War II had provided economic opportunities for Latina/o immigrants, found itself in steep decline. As the historian A. K. Sandoval-Strausz has shown, federal policies to transform the city and subsidize the suburbs resulted in an urban crisis that triggered “population loss, economic decline, fiscal crisis, rising crime, and the racialization of all of the above.”9 This toxic mix resulted in a lack of city services, housing displacement, and the continued criminalization of black and brown bodies. Caught in the middle of this urban drama were religious institutions that debated whether they should uproot and move to the suburbs or stay and join the fight to save the neighborhood. The choice was not always clear. Urban renewal policy and programs, as it turns out, posed a significant challenge to Protestant and Catholic churches, many of which found themselves in the crosshairs as neighborhoods changed. But religious institutions were also experiencing transitions of their own. The late 1960s ushered in an era of deep ecumenical awareness and activism that shifted urban religious politics from “reconciliation to revolution.”10 This created tensions between a cohort of religious leaders interested in studying theology against the backdrop of the urban crisis and others interested in closing churches and starting over in the suburbs. In the end none of that mattered. Whether churches stayed in the city or took the highways to the suburbs, they could not escape the fact that their buildings—and their space—offered hope and possibility for activists looking for a place to stage their movements.

«4»

Apostles of Change

On their own, these occupations and disruptions were dramatic instances that faded almost as immediately as they rose. Each occupation lasted no more than five to twenty days before church officials sought legal help to force the activists out of their churches. In the case of Católicos Por La Raza (CPLR: Catholics for the People) in Los Angeles, the disruption lasted one spectacular night. Yet each story not only gripped the headlines and frightened white religious leaders across the country but inadvertently buoyed the causes of Latina/o religious insiders (Protestant and Catholic clergy and laity), whose movements for more visibility within church structures had taken root but remained marginal. That is not to say that Latina/o religious insiders supported the occupations and disruptions (many did not), but these actions did move them to the center of the discussion on race and power, which until then had centered on black and white tensions in the church. The brevity and sensational theatrics of these occupations, and what they teach us about the unlikely relationship between Latina/o radical politics and religious leaders, have remained an untold story until recently. Part of the problem is that in their immediate aftermath evangelical news outlets like Christianity Today disregarded their importance, calling the Young Lords “gangs” that trashed churches and left “extensive damage . . . including Marxist posters and stacks of revolutionary literature advocating violence.”11 These dismissals are even more pronounced in the historiography of the Religious Left, which for the most part has ignored the participation of Latina/os in the urban religious politics of the late 1960s and 1970s.12 These studies typically highlight the relationships that progressive clergy forged with urban agencies and city leaders with no real benefit in the end. I flip the script in these pages by focusing on an overlooked aspect of the urban crisis that brought two diametrically opposed groups to the negotiating table: Latina/o radicals and religious leaders.13 Latina/o religious studies scholars have also turned a blind eye, preferring instead to remain tied to large-scale events such as Vatican II and the rise of liberation theology in Latin America as the most important factors in shaping Latina/o theology and religious politics in the United States. While both developments transformed theology and politics, in this book I take a closer look at what a few relatively unknown church occupations— rooted in neighborhood struggles—tell us about religion, revolutionary politics, and the urban crisis of the late 1960s. Specifically, I outline two distinct interventions in the fields of American religion, urban history, and Latina/o history. First, in focus-

Introduction

«5»

ing on church occupations and disruptions, the book reveals what other histories have ignored or regarded as insignificant: that the boundaries between faith and politics in the Latina/o freedom movement were frequently crossed and that, at least for a moment, a robust relationship existed between young radicals and religious leaders.14 These short but fertile political moments, and the politics that emanated from them, shined a light on Latino Protestant pastors and Catholic clergy and gave them a national platform from which to advocate on behalf of the religious communities they represented. In each of these cases, Latina/o radicals breathed life into faith politics, joined the language of liberation theology with the rhetoric of radical Latina/o politics, pushed back against urban renewal, and in the process opened new possibilities for Latina/o religious reformers, some of whom opposed the radical politics of these groups. In other words, Latina/o radical politics paved the way for reformist politics within the church. Sociologists call this the “radical flank effect,” when an action by a radical group strengthens the bargaining position for a more moderate group that makes the demands being made by the moderate group seem reasonable.15 While Latina/o religious leaders already had a long and active history of engaging their white religious leadership, most notably in the farmworker movement, the occupations and disruptions in 1969 and 1970 moved them from the margins to the centers of religious power in Protestant and Catholic churches. Latino pastors, from the Presbyterian Latin American Caucus to the Catholic group PADRES, owe their political rise to Latina/o radical activist groups. Second, I begin from the premise that an analysis of church occupations allows for a more complex reading of the Latina/o freedom movement in the late 1960s and 1970s and expands our understanding of the role that religion played. They call attention to the interrelated ways that religious reformers and Latina/o radicals clashed, collaborated, and negotiated space in neighborhoods and in churches. But this is more than simply a narrative about how faith inspired social protest. This book is about how nonreligious actors who were revolutionary activists— whom I call religious outsiders—occupied churches as a way to inspire faith communities to get involved in the struggles of the neighborhood. Rather than accept the church as an oppositional force, Latina/o activists—from Chicago to Houston and Los Angeles to New York— understood the church to be a contested public space that offered possibilities for both spiritual and social engagement. And while the Young Lords sharing space with the United Methodist Church and the Mexican

«6»

Apostles of Change

American Youth Organization (MAYO) activists negotiating with Presbyterians in Houston might seem like an odd mix, the secret affinities between unlikely groups provide a glimpse into movements that questioned the role of churches in neighborhood politics, drew attention to interethnic coalition politics, and blurred the lines between the sacred and the profane on the streets of urban America.16 The following pages present both a religious history of the Latina/o freedom movement and a social movement history of religion. My aim here is to remind readers of, or at least make it more difficult to ignore, the religious politics that underwrote the Latina/o freedom movement. The radical and reformist strains in Latina/o communities varied and diverged but at moments intertwined and worked off each other to achieve the dreams they dreamed. I focus on church occupations and disruptions by Latina/o activists with the ultimate task of providing a deeper analysis of what radical politics looked like, its multiple expressions, and its clashes with reformers as the young radicals pressed forward to save their barrios.

El Barrio, Religious Activism, and the Politics of Occupation The neighborhood, or barrio in this case, is the centerpiece of Chicana/o and Latina/o history. From Albert Camarillo’s classic text Chicanos in a Changing Society to Virginia Sánchez-Korrol’s From Colonia to Community to more recent work on Dominicans in New York’s Washington Heights and Latina/os in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, place matters in Latina/o history.17 It makes sense, then, that the barrio is a natural starting point as we think about conceptualizing Latina/o freedom movements that incorporate the experiences of multiple groups of Latin American origin in the United States. In this context the barrio is not viewed as a monolithic utopia but as a place where working-class sensibilities and cultural resilience come face to face with chronic poverty, uneven development, and limited educational opportunities. If the barrio is the central place in Latina/o history, displacement is its main story. As a consequence of urban renewal policy, displacement emerged out of an urban plan that worked to keep blacks and Latina/os away from commercial districts with strictly enforced segregation. In the years after World War II profound urban segregation and disinvestment in Latina/o neighborhoods led to what George Lipsitz has

Introduction

«7»

called “social subordination in the form of spatial regulation.”18 At its core, urban renewal capitalized on rising property values and the development of commercial districts to reshape cities across the country. This process, as historian Lilia Fernández aptly put it, turned Mexicans and Puerto Ricans into “expendable populations” that experienced “repeated dislocations that dispersed them across multiple neighborhoods and geographic communities in the urban core.”19 Yet as significant as this history of displacement has been, the history of Latina/os and urban renewal policy remains sorely understudied in the field of urban history. This has changed somewhat in recent years with the works of Lilia Fernández, Llana Barber, Eduardo Contreras, A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, and others.20 All these texts are significant and pathbreaking in their own right. I build on them even as I delve into new territory of the urban crisis by examining the church occupations and disruptions in barrios across Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Houston, the four largest and most diverse cities in the United States. But demography has never been destiny for any of these cities. Each of these cities has large black and brown populations as well as a deep and entrenched history of antiblack and antiLatina/o racism. Martin Luther King Jr. once proclaimed that Chicago was a city plagued with more racism than the deep South; Los Angeles is the prison capital of the world; New York has a history of police violence against black and brown communities; and Houston, with its legacy of slavery, westward expansion, and Jim Crow segregation, is known best as a “western South” city.21 These cities are also tied together by a history of strong and sustained freedom movements born in Chicana/o and Puerto Rican barrios where young people organized for a better education, for political representation, and for community control. In addition, they are sites where Latina/o radical groups staged some of their most forceful movements from the pews and altars of churches in their neighborhoods. I begin my account in Chicago not only because it was the first occupation (May 1969) but also because Chicago was in many ways the vanguard of the Latina/o freedom movement in the late 1960s. With large populations of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans living in close proximity with blacks and whites, the city gave rise to the Young Lords Organization (YLO), a group that shifted from gang activity to political protest in the late 1960s. The Young Lords were predominantly Puerto Rican, but their members included Mexican, black, and white activists. Latina/o activists in Los Angeles, New York, and Houston all looked to the work

«8»

Apostles of Change

of the Young Lords in Chicago for inspiration as they organized movements in their own neighborhoods. The Presbyterian pastor Tony Hernández in Los Angeles, Gregory Salazar in Houston, and Iris Morales in New York all pointed to meeting or at least hearing about José “Cha Cha” Jiménez (the founder of the Young Lords in Chicago) and the movements and coalitions that they organized there.22 In each of these cities, Latina/o radical groups—the Young Lords in Chicago and New York, Católicos Por La Raza in Los Angeles, and the Mexican American Youth Organization in Houston—waged smart and calculated fights against religious leaders as a way to claim space, offer social services, and push back against the displacement plans of urban renewal policies. Of course, each of these groups emerged in a different context and in a different neighborhood, but they were all driven by a love for their community and a respect for the power of religious institutions. The Young Lords emerged out of Lincoln Park in Chicago and East Harlem in New York. The Mexican American Youth Organization came out of San Antonio, the Rio Grande Valley, and Houston’s Northside neighborhood. Católicos Por La Raza (a different group altogether) represented a who’s who of activists from across Los Angeles who came together in a spectacular way in 1969.23 The politics and ideologies of these groups varied, expressed and practiced differently based on their regional contexts, but in general they all focused on racial and socioeconomic inequality and believed that their movements formed part of an international struggle not limited by arbitrary national borders. The Young Lords had clearly defined political and ideological commitments to building a socialist society as revolutionary nationalists. MAYO practiced a political pragmatism that emerged out of Houston’s location as a southern and western city. Católicos Por La Raza’s ideology was a mixture brought in by the array of activists from Los Angeles who joined the movement.24 In order to discover what linked these groups together, I categorize them together as part of the constellation of Latina/o radical activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, each of the groups that I follow here ascribed more directly to internationalist positions that, as George Mariscal argues, “ranged from simple acts of solidarity embedded in a liberal framework to fully developed critiques of capital’s role in U.S. society with an emphasis on the imperial past and present of the United States.”25 In each of these four stories, Chicana/o and Puerto Rican revolutionaries occupied churches and disrupted services as a way to call an end to the racism and capitalist exploitation that undergirded urban renewal plans in the 1960s.

Introduction

«9»

Writing the story in this way—starting in the barrio but conceptualizing these occupations relationally rather than as isolated events—means centering on Chicana/o and Puerto Rican movement engagements with religious groups, particularly Christians. Doing so requires expanding the field of vision and taking an outside-in view (with a focus on secular and nonreligious activist engagements with the church) of Latina/o religion rather than an inside-out view (with a focus on clergy and religious leaders). Following the lead of the religious historian Josef Sorett, who argues that “one need not be IN an actual church to be OF the church,” I take seriously the claims and positions of secular and nonreligious political engagements with both Protestant and Catholic churches.26 Writing this history any other way only feeds into the myth of a secular Chicana/o and Puerto Rican movement. In his work on the relationship between black Catholics and Black Power, Matthew Cressler tackles this myth head on by pushing back against the “way in which ‘militancy’ and ‘radicalism’ come to serve as code words for ‘secular’ and ‘nonreligious.’”27 This is also the case in Latina/o history, where religion is most often ignored or simply not important enough for consideration when writing about political movements. But a closer look at the evidence reveals a deep and complex relationship. In some cases, clergy stood in solidarity with Chicana/os and Puerto Ricans; in other cases, however, religious outsiders—Latina/o radicals—took the fight to a church and forced it to reconsider its relationship to the neighborhood. In other words, the radicalism and nationalist politics of Latina/o activists reinforced the need to reform the church rather than ignore it as an irrelevant institution. This political and religious engagement forces us to reconsider the importance of religion in the Chicana/o and Puerto Rican struggles and breaks down the assumption that cultural nationalism is solely to blame for religion’s absence in much of the historical literature. In the late 1960s and 1970s Latina/o radicals recognized that everyday forms of religious devotion provided an “orientation,” a way to make sense of the world, and a catalyst to the forms of resistance and adaptation that have defined the Latina/o experience in the United States.28 After all, this was the period that witnessed the largest and most expressive form of clergy activism in the United States. Clergy, of all faiths, took to the streets in solidarity with those advocating for social change. The church—the collective body of believers—became the staging ground for the black freedom struggle in the 1950s and 1960s and also provided the institutional support necessary for the farmworker movement in cen-

« 10 »

Apostles of Change

tral California to launch the most successful agricultural rights movement in US history. This was no accident. Religious leaders had access to large networks, had ministerial authority to sway the opinions of people in the pews, and centered segregation, labor rights, and racial injustice as more than social issues in need of a democratic remedy. In the early 1960s Pentecostals were on the front lines helping Cuban refugees adjust to their new surroundings and establishing refugee centers in Florida. When over 14,000 Cuban children were boatlifted from Cuba during Operation Pedro Pan, Pentecostals were there to provide refuge and minister to the needs of the children.29 Most scholars agree that these movements were energized by theological and ecclesiastical movements that promised to transform the Catholic church. The decisions that came out of Vatican II (1962–1965) moved the Catholic church away from its fortress-like presence to become a church that vowed to engage the world and initiate a dialogue across faith traditions and practices. Vatican II was indeed a revolutionary move for the church that spoke of “the whole people of God.” In 1968, at a meeting of Latin American Bishops in Medellín, Colombia, bishops denounced “institutional violence” and made a clear and decidedly theological “preferential option for the poor.” This structural change came on the heels of a global realignment whereby Christians in the Third World began questioning the authority of the institutional church and its role in the world.30 This movement, and most notably the writings of the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, laid the groundwork for liberation theology, which stresses that the church must do more than simply empathize with and care for the poor: it should work for fundamental political and structural changes to eradicate poverty. Poverty and economic injustice were no longer simply an economic condition but were now labeled as “sin” by liberation theologians. This made an important impact on Latina/o Christians in the United States and moved the church to deal with its exclusions in ways that it had not done before. The civil rights movement in the United States confirmed the post– Vatican II idea that all Catholics—not just the leadership—could be a force for change within the church. For mainline Protestants, the support emerged most strongly within the farmworker movement. In fact, it was mainline Protestant groups, specifically the California Migrant Ministry, that Cesar Chavez first called to get his support for the boycott that the National Farm Workers Association joined in 1965 in Delano, California.31 In the 1960s and 1970s the Virgen de Guadalupe’s image was often front and center for the largely Catholic Mexican and Mexican

Introduction

« 11 »

American population of farmworkers fighting for better wages and better working conditions. Latina/o clergy and leadership played small, but significant, roles in many of these movements as advocates for their own religious traditions on behalf of farmworkers. But outside of the token recognition of the exploitation of farmworkers, Catholic and Protestant leaders—black and white—had little or no understanding of the issues that affected the Latina/o community in terms of housing, segregation, and education. Liberal Protestants who started joining the critiques of urban renewal and became enamored with the black freedom struggle remained wholly ignorant of the conditions in which most Latina/os lived and worked. This ignorance has seeped into the literature of the Religious Left, where Latina/os are at worst completely ignored or at best seen as marginal to the larger story of civil rights, religious renewal, and Black Power.32 This is surprising, given the coalitions, movements, and collaborations that Latina/o revolutionaries created with Black Power advocates. To tell the story of the urban crisis without placing it within this multiracial context is to ignore one of the movement’s most powerful strategies: black and brown coalition building. Much of this coalition building took place in the spaces and places that activists chose to occupy as a way to reclaim their neighborhoods. And in the 1960s few other movement strategies captured the imaginations and hearts of urban communities more than occupation did. To occupy—to reclaim space—emerged as a powerful strategy as marginalized groups claimed dignity and citizenship rights and fought for the right to stay in the neighborhood. The bigger the space, or the more iconic the building, the better. The factors that make a building or space a symbol of great power, as Tim Cresswell argued, “simultaneously make them ripe for resistance in highly visible and often outrageous ways.”33 In this sense, 1969 gave us some of the most iconic occupations in social movement history. The group known as Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz island in November 1969. The nineteen-month occupation launched the Red Power movement and inspired more occupations across the country, from Wrigley Field to Fort Lawton. At the very moment when Católicos Por La Raza disrupted Christmas Eve mass in Los Angeles and the Young Lords occupied the First United Spanish Methodist Church in East Harlem (both in 1969), the Red Power activists who occupied Alcatraz island were decorating their Christmas tree with ornaments that represented the love and struggle of previous generations

« 12 »

Apostles of Change

and held a celebration with “Indian singing, Indian music, Indian food, and speeches.”34 The occupation of Alcatraz island has become perhaps the most wellknown case, but in examples across the country occupation served as an important strategy to reclaim space, claim dignity and citizenship rights, and fight for the right to stay in the neighborhood. The move to occupy the church—as a symbol of power—and to disrupt Christmas Eve mass in Los Angeles was itself an outrageous argument against displacement. In each of the stories in this book, Latina/o activists ultimately were pushed out and, in the end, defeated, but the optics and rhetoric of occupation have lingered. Seeing these young radicals serve breakfast inside the church, cite Bible verses, and proclaim that the church belongs to the people shocked and motivated religious leaders to take action at some of the most iconic and historic institutions in the country: the Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches.

Sacred Space, Sacred Resistance One of the most poignant scenes in the Gospels is Jesus turning over tables and driving out the money changers from the temple. Each gospel tells a slightly different story from a slightly different vantage point. In the Gospel of John, Jesus walked in with a “whip of chords” (John 2:15, New Revised Standard Version, NRSV), angered at what he saw, driving out animals and merchants and demanding that they “stop making my Father’s house a marketplace!” (John 2:16, NRSV). Chaos ensues. The Gospels of Luke and Mark note that Jesus shut down the temple, occupied the building, and continued teaching. This was impressive, given that on this day thousands of pilgrims, priests, men, women, Gentiles, and merchants would have populated the area. The temple had become a “den of robbers” (Luke 19:46, NRSV) where only a selected few were welcome: the notion of “a house of prayer for all the nations” (Mark 11:17, NRSV) was lost. The temple was transformed into an exclusionary place under the control of the priests and the Pharisees. This event marked an important part of the ministry of Jesus: his stance against religious authorities. The Alexandrian exegete Origen argued that “Jesus’ overturning of the tables was a feat even greater than his changing water into wine.” The theologian Nicholas Perrin called the action a “self-defining” moment for Jesus that brought all his ideas about the Kingdom of God into one particularly violent action at the temple.35

Introduction

« 13 »

The action was critical to Jesus’s ministry and one of the reasons why he was arrested and later crucified. His actions were seen as a threat to the established religious order and thus a threat to the Roman Empire. The fight was about religious insiders and outsiders in the temple, those welcome and those unwelcome, and about Jesus’s anger at these exclusionary practices. To fully understand the politics of Jesus, in other words, we must fully grasp the power, violence, and anger displayed at the temple cleansing. The drama of Jesus storming the temple, driving out the merchants, and occupying it as a way to restore it provides a powerful parallel to the actions of Latina/o radicals in 1969 and 1970. Like Jesus’s action in the temple, the church occupations are one piece of a large and complex puzzle that illustrates the relationship between religion and radical politics, a relationship rooted in struggle. In Latin American independence movements especially, religion has served as a major force of inspiration. On the morning of September 16, 1810, the Catholic priest Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla invoked the powerful and unifying symbol of the Virgen de Guadalupe to promote the cause of Mexican independence as he gave el grito de Dolores and called people to join in the cause of Mexican independence.36 In the twentieth century the Puerto Rican nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos equated Puerto Rico’s independence movement with the highest of Christian aspirations. Other Puerto Rican nationalists followed this trend as they organized the Arizmendi Society (named for the first Puerto Rican bishop) as a way to promote their cause of independence. They believed that the key to gaining a national consciousness was having more native priests and gaining a militant connection to independence groups, clearly linking their Christianity with revolution.37 In the modern era the link between revolution and Christianity has not always been as clear. Perhaps the most familiar instance was the Black Manifesto in May 1969, which demanded reparations for the historic role of religious institutions in the enslavement of black people. Drafted by former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist James Forman, the manifesto demanded $500 million from white churches and synagogues in reparations.38 The effects were felt almost immediately. By the end of May 1969 Forman had placed demands before the United Church of Christ (UCC), United Presbyterian Church in the USA (UPCUSA), Lutheran Church in America, American Baptist Convention, United Methodist Church, and Episcopal Church. By the first week of June black and white seminary students and activ-

« 14 »

Apostles of Change

ists had occupied the offices of the National Council of Churches, UCC, UPSCUA, and Reformed Church in America in New York City. Protestant denominations were caught flat-footed as Forman’s movement inspired a wave of support from young and progressive Christians. But the response was mixed. The American Lutheran Church noted that the manifesto was rooted in “anguish and frustration in a segment of our society but added that portions of the document were inflammatory, filled with hate and must be repudiated.”39 Negative reactions also came from some black religious leaders. The Reverend J. H. Jackson, president of the national Baptist Convention USA, the nation’s largest group of black religious leaders at the time, argued that the manifesto is “the same old Red manifesto painted black and an echo of the Communist demands of Karl Marx.”40 Some called Forman a modern-day prophet; others ridiculed his bombastic behavior and chastised him for what they believed were ridiculous demands. While the manifesto did not come close to reaching the $500 million figure, it did compel Protestant denominations to fund more moderate projects related to racial reconciliation, community development, and economic empowerment in black communities. Groups like the Episcopal Church gave $200,000 for the National Committee of Black Churchmen, the United Presbyterian Church in the USA pledged to raise $50 million for antipoverty work, the World Council of Churches created a $200,000 reserve fund for oppressed people, and the Riverside Church in New York City, which was specifically targeted by Forman, created a fund for social justice work among New York City’s poor.41 While the Black Manifesto sparked much debate on the relationship between Black Power and American Christianity, and justifiably garnered significant attention in 1969, it was only one part of a larger push to reclaim sacred space in the United States. In the late 1960s churches and religious institutions found themselves in the middle of the fights against urban renewal, poverty, and the lack of health care in cities across the United States. The story of Latina/o freedom movements at these holy sites across the country forcefully illustrates how the church became the site of a dramatic and important struggle. The right to stay, the right to live freely, the right to gather for the common good, and the right to reconfigure space—to crash the sacred and the secular—and to think of the church as both a holy site and a community site—were at the heart of the matter in each church occupation and disruption. This explosion in the role of the church as a site of struggle in the late 1960s points to the

Introduction

« 15 »

complex relationship between religion and radical activism. While biblical references were often absent in the Chicana/o movement narrative, activists understood the sonic, visual, and artistic power of spirituality and religion. From Reies López Tijerina’s spiritual visions to Martha Cotera’s notion of “Diosa y Hembra” (Goddess and Female) to describe Chicanas in the movement, the role of faith and spirituality has always lingered in the back—shaping rhetoric, infusing hope—even as movement leaders rejected the implications of the supposed reformist ends of religious leaders.42 It never ceases to surprise me that the Chicana/o movement in particular has generally been portrayed as unconcerned with, if not opposed to, religion and religious institutions. Where religion has figured into the story, it has almost always appeared as inconsequential, tangential, or only in figures and symbols of Guadalupe leading a group of farmworkers. Perhaps this is because the movement cast itself as secular humanist, with Marxist-Leninist leanings. But those ideological commitments were uneven, especially when activists engaged religious leaders. As much as Latina/o radicals chastised the church as an oppressive institution, they remained open to working and collaborating with religious leaders. Activists often relied on the church for space, for support from clergy, and for financial support. In this regard, no religious organization was more active in funding Chicana/o movement projects than the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO). Between 1968 and 1971 IFCO contributed well over $250,000 to projects that ranged from community organizing in San Juan, Texas, to farm labor organizing in Toledo, Ohio, to union work in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.43 But to be clear, I am not suggesting that activists in the Young Lords or the Mexican American Youth Organization considered themselves religious or that these were religious movements. I do not believe that they were. But I believe that activists in these movements did carry with them a spiritual consciousness developed in them during their own upbringing. Many of the activists I cover in this book were raised in homes where Catholicism and/or Protestantism was an essential element of life. For many of these activists, spiritual consciousness was rooted in a sense of peoplehood that opened possibilities and relied heavily on the memories of a radical and revolutionary Christ as portrayed in the Gospels. This is why many of the activists were able to cite biblical justifications for their church occupations, especially in the People’s Church in New York City. Their spirituality broke down institutions, recognized the power of the community, and believed in the shared religious author-

« 16 »

Apostles of Change

ity of clergy and laypeople alike. A spirituality has always existed outside of the realm of the institutional church that is pragmatic and focused on this world, rather than the one to come. In each story discussed in this book, the occupied churches, whether made up of working-class Catholics or Protestants, were always treated with respect and with great care. Members of the Mexican American Youth Organization in Houston immediately replaced the window they broke as they entered the building. Yes, these activists were pointing out the beam of wood in the eye of the church, but that was not the complete story. They also showed a deep sense of love and respect for the sacred space they occupied. The story of church occupations and radical politics is intertwined with another important element in this book—sacred space. Latina/o radicals imagined the sacred space of the church as more than a building where salvation is found: they saw it as a physical space to meet the community’s social needs, which offers refuge to the oppressed and is committed to a preferential option for its neighborhood. The church became a resource: not simply something to occupy, but something to protect. While in each case Latina/o activists were forced out of the church, drowned out, beaten by police, with lights cut and gas cut—in every case they were driven out by religious authorities—the occupations struck a nerve. They not only moved entire religious institutions but also strengthened moderate religious groups.44

Itiner ary This book travels through four different cities as a way to weave together the narrative of Latina/o freedom movements. Chapter 1 stops in Chicago to examine the occupation of the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood in May 1969. The Young Lords assembled a “rainbow coalition” of black, brown, and white activists who occupied the seminary for five days and in the months that followed secured funding for a legal aid office, a health clinic housed at the nearby Armitage Methodist Church, and a proposal for low-income housing in Lincoln Park. While the occupation only lasted five days, it started a local and national conversation that for the first time put Latina/o urban politics at the center of a larger conversation about race, urban space, and theology. Chapter 2 investigates the politics that led a group of Chicana/o ac-

Introduction

« 17 »

tivists to disrupt Christmas Eve mass in the beautiful new St. Basil’s Church in Los Angeles. That evening in 1969, only months after the occupation of the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago, the group known as Católicos Por La Raza clashed with police and church leadership in an effort to make the wealthy St. Basil’s Church respond to the social needs of the surrounding Chicana/o community. As you will notice, this story is somewhat different for two reasons. First, Católicos did not occupy a building but instead disrupted a Catholic mass. Second, the chapter is focused more on the actual event and delineating a complex moment that provides a view into the diversity of the Chicana/o movement in Los Angeles. The story of the CPLR follows the thesis of the book by investigating how this revolutionary action opened doors for religious reformers within the church but also points to the diversity within the movement—a coalition of Immaculate Heart nuns and Chicana/o radicals—at this particular moment in 1969 in Los Angeles. Chapter 3 follows the occupation of the First Spanish United Methodist Church (FSUMC) by the Young Lords in New York City. The church, which was located in the historic Puerto Rican neighborhood of El Barrio in East Harlem, remained in the control of the Young Lords for two weeks during the last days of 1969 and into 1970. During that time, they managed to offer a variety of social services, including a free breakfast program and cultural identity classes. The church was not only located in the center of El Barrio on the corner of 111th Street and Lexington Avenue but was used only a few hours a week, remaining empty the rest of the time. The political indifference of the FSUMC was even more pronounced when compared to the work of Catholic churches in the neighborhood, all of which operated some kind of antipoverty program. This chapter examines the legacy of the occupation of the First Spanish United Methodist Church on the Puerto Rican religious politics that emerged in New York in the 1970s. Chapter 4 travels south to Texas to follow the politics and engagements of the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) in Houston. The chapter focuses on the long and drawn-out occupation of the Juan Marcos Presbyterian Church in 1970 by MAYO. The occupation of the Juan Marcos Church, located in the heart of Houston’s Northside neighborhood, lasted the longest of any covered in this book (twenty days) and took place in a church that was empty at the time. When it was occupied, the Christ Presbyterian Church (later changed to Juan Marcos Presbyterian Church) was in the midst of a demographic transition, fifteen years in the making, that saw white residents leave and black

« 18 » Apostles of Change

and brown residents move into the barrio. This chapter examines how white Presbyterians and Chicana/o activists negotiated the politics of a neighborhood in transition even as they fiercely debated the role that the church could and should play in community activism, politics, and social change. In the process, the occupation helped transform MAYO from an unknown organization in the Northside to a major player in Houston’s civil rights politics in the early 1970s. The final chapter assesses the major findings of the book, points forward to the implications of the occupations for Latina/o religious politics in the 1970s and 1980s, and provides an analysis of the political and religious ideas that tug at the heart of the Latina/o freedom movement. I end with a nod toward the future and a reminder that the Religious Left did not die, diminish, or lose power. Instead, the Religious Left got to work at the grassroots level, back to the roots of Latina/o activism, back to the barrio. While religious studies scholars mourned the loss of the Religious Left and the meteoric rise of the Religious Right, they missed the reality that the Religious Left emulated and was a reflection of the local and barrio politics that have always been the centerpiece of the movements for liberation and freedom of Latina/os in the United States. Telling these stories reinforces once again that the power of the Chicana/o and Puerto Rican freedom movements resides in local spaces and neighborhood struggles, guided and inspired by national and transnational movements, where the ideas for social and political liberation are firmly planted. I hope to show how Latina/o activists imagined a new future, their struggle to build the People’s Church, and the negotiations and political moves that they made along the way. They were savvy political actors who took seriously their responsibility to dream new dreams and envision new visions. My further hope is that this book might compel us to take seriously the role of sacred spaces in our collective efforts to build a better world. One of the most inspiring aspects of writing this book was learning what went on inside the occupied churches. Inside these churches, young people sang together, read poetry, imagined a new world, and strategized for a total transformation of society. They joked, played together, and cried together as they fought for their barrios. I wrote this book to tell these stories, not only because they are inspiring, but also because they provide a way to shift how we remember the Chicana/o and Puerto Rican movements. Despite the problems, failures, rejections, and limits of these movements, they remind us always to keep the faith, to never give up hope.

Chapter One

Thunder in Chicago’s Lincoln Park

This is a new style of confrontation . . . not only poor, but black or brown. . . . We are frightened by their demands. We want them to behave like us, to play the game as we do, to listen to what we tell them is for their own good—and, if they will not, we respond as frightened men, violently. Arthur McK ay, pr esident, McCor mick Theological Seminary1

Poor people in the Lincoln Park area got it together like no mixed group of poor people in this country. . . . Latin, Black, Southern White, and other poor and working class whites held the Manuel Ramos Building (called the Stone Building by the Seminary). . . . They questioned the legitimacy of the institution and its power. Lincoln Park Press2

If in fact you are interested in eliminating racism, then we should not leave here until there are some answers to the demands made by Spanish-speaking and black people of this country. James For man, Black Economic Development Cou ncil, at the 181st Gener al Assembly of the U nited Pr esbyterian Church USA, 1969

T

he people gathered at Orlando Dávila’s home on the night of May 3, 1969, saw it all happen. First they heard shouting from the street in front of Dávila’s house, then they realized that it had come from a man with a gun pointed right at them. The next

« 20 » Apostles of Change

moment two shots were fired. One of those shots hit Manuel Ramos in the head, near his right eye. Another shot hit Rafael Rivera in the neck. Chaos ensued when the man with the gun, later identified as an off-duty police officer, James Lamb, was seen walking away; some reported seeing him walk back into the apartment that he was painting at the time. Lamb later testified that he fired his weapon only after he heard shots fired from across the street. When he proceeded to investigate, he reported, he saw three men and heard one of them say, “Get away from there or I’ll blow your head off.” He said that another man reached for a weapon. Witnesses refuted Lamb’s testimony, arguing instead that the police officer was the aggressor. The remaining details of that night are murky, but we know that Manuel Ramos and Rafael Rivera were taken to the hospital. Four of their good friends—Pedro Martínez, José Lind, Sal De Rivero, and Orlando Dávila, all part of the group that called themselves the Young Lords Organization (YLO)—were arrested, taken into custody, and tried for assaulting a police officer. Manuel Ramos died later that night. James Lamb, the police officer who shot and killed him and wounded Rivera, was cleared of any wrongdoing by a coroner’s jury.3 Manuel Ramos was a father, a husband, and a brother. His death robbed his two children, a two-year-old daughter and six-month-old baby boy, of their father. Those who knew him best described him as a quiet, mild-mannered man.4 He served as minister of defense for a Young Lords Organization that in 1969 was still trying to find its way, still working to see how best it could help the community, still learning the intricacies of revolutionary politics. Ramos’s death, however, would serve as a turning point for the young activist group. His death brought together his fellow Young Lords from the Lincoln and Humboldt Park neighborhoods as well as members of the Black Panthers and the white Appalachian group known as the Young Patriots at his memorial service at St. Teresa’s Catholic Church. Together they stood silently in respect, observing religious rituals in Ramos’s honor. His death, and the solidarity that came from black and white revolutionary groups, sparked a political fire in members of the Young Lords Organization. It was also a key moment for the young leader of the YLO, José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, who later confessed to the journalist Frank Browning that the murder of Manuel Ramos was the “point that I became a real revolutionary.”5 Manuel Ramos’s death added fuel to an already active organizing presence in Chicago neighborhoods—from Uptown to Lawndale to Lincoln Park—as multiple groups turned up the heat in the summer of 1969. Black, Latina/o, and white activist groups occupied institutions, estab-

Thu nder in Chicago’s Lincoln Park

« 21 »

Figur e 1.1. The Young Lords and others protesting the fatal shooting of Manuel Ramos, May 5, 1969. Photo, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, Chicago History Museum/Getty Images.

lished breakfast programs for schoolchildren, organized rallies, opened health clinics, and published newspapers that promoted solidarity. Each of these movements was significant, but none more so than the takeover and occupation of McCormick Theological Seminary. Days after Ramos’s death, members of the YLO, together with a coalition of community groups known as the Poor People’s Coalition (PPC) and with help from seminary students, walked onto the campus of McCormick Theological Seminary, located in the heart of Lincoln Park, and occupied the newly renovated Stone Academic building. They chose to occupy the seminary rather than DePaul University or the Children’s Hospital, two other institutions in Lincoln Park, because McCormick was the weakest institution in the triad, and the YLO believed that it could exploit the seminary’s hypocrisy. With placards that read “I was cold and alone, and the Christians took my home,” activists accused seminary leaders of standing idly by as urban renewal displaced low-income families in Lincoln Park.6 After the occupation, the activists renamed the structure the Manuel Ramos Building as an homage to their good friend and a signal to the institutions in the neighborhood that urban renewal, or “urban removal” as they called it, was not going to happen without a fight.7

« 22 »

Apostles of Change

Much of the literature on the Young Lords specifically and on Latina/o Chicago more generally treats the McCormick Theological Seminary as a one-dimensional space, as a conduit for urban renewal, and as an isolated institution with few ties outside of Chicago. Scholars’ assessment of the McCormick occupation has been limited by their failure to engage religious archives and primary sources written by religious leaders themselves. This not only has shortchanged the important work of the Young Lords and the Poor People’s Coalition but also has limited our understanding of this turbulent moment in US and global urban religious politics. Religious groups in the United States and across the world experienced a metamorphosis in the 1960s and 1970s. Anticolonial movements globally, the civil rights movement at home, Vatican II, the rise of liberation theology in Latin America, religious pluralism as a result of increased immigration, and the “Death of God” movement shook religious institutions to their core. When the Young Lords led a coalition to occupy McCormick Theological Seminary, which belonged to the United Presbyterian Church in the USA (UPCUSA), one of the wealthiest religious groups in the United States, they unwittingly walked into a struggle that was much bigger than their fight against urban renewal in Lincoln Park. This chapter focuses on the struggle against urban renewal in Lincoln Park by zooming in on the occupation of McCormick Theological Seminary in May 1969. I argue that the McCormick occupation propelled the Young Lords and Latina/o radical politics onto a national religious stage in two primary ways. First, the Young Lords and their coalition were successful in winning some of their demands from the seminary and the UPCUSA. Led by their chief negotiator, Obed López, who was raised in a Protestant home in Mexico, the Young Lords secured funding for a proposal for low-income housing in Lincoln Park, a legal aid office, and a health clinic housed at the nearby Armitage Methodist Church. While the occupation only lasted five days, it started a local and national conversation that for the first time put Latina/o urban politics at the center of a larger conversation around race, urban space, and theology. Second, the occupation of McCormick seminary paved a political path for the historically reformist Latina/o Presbyterian leadership in Chicago. Almost overnight Latino clergy found themselves the darlings of the Chicago Presbytery, which prior to the occupation had ignored their proposals for church service work. Latina/o Presbyterians, whose

Thu nder in Chicago’s Lincoln Park

« 23 »

voice had always sounded “like far off thunder” coming from a group whose issues were “only just beginning to come to the surface,” positioned themselves to lead the church both theologically and politically in the 1970s.8 The twists and turns of this story reveal the deep love that the Young Lords had for Lincoln Park and how their “act of love,” as Obed López described the occupation, kicked off a trend across the country as Mexican American and Puerto Rican activists took their struggle to the very centers of American political and religious life. This story starts not with the McCormick occupation but with the story of a city seduced by the appeal of urban renewal in the postwar era.

Displacement as Prologue The origins of the Young Lords Organization in Chicago, which transformed from a street gang organized in 1959 to a revolutionary nationalist group a decade later, are rooted in fighting for a particular place: the Lincoln Park neighborhood. As social servants and revolutionary nationalists, members of the YLO organized a local movement with an eye toward anticolonial movements in Puerto Rico and across Latin America and Africa. “Our mission was self-determination for Puerto Rico and other nations in Latin America,” Cha Cha Jiménez, one of the group’s founders, explained, “and neighborhood empowerment, that was our mission.”9 At the center of this neighborhood empowerment was Lincoln Park. The Lincoln Park neighborhood is located in the North Side of the city, enclosed by Diversey Parkway to the north, North Avenue to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, and the Chicago River to the west. In the 1960s the neighborhood was defined by both its ethnic mix and the shared experiences of displacement.10 From Victorian brownstones near the lake on the east to immigrant housing units to the west, and with plans for a shopping district with restaurants and entertainment possibilities, Lincoln Park was one of the most competitive real-estate markets in the city. In addition, the triad of institutions in the neighborhood—McCormick Theological Seminary, DePaul University, and Children’s Memorial Hospital—made significant investments. Properties sold quickly in this market, so urban renewal hawks targeted Lincoln Park. But the urban renewal trend started much earlier as a move to keep the triad of institutions from leaving Lincoln Park for greener city

EL

ST

ON

E

DAMEN AVE

nch V NA

ke n La iga ich M

HAMMOND

TO

OAK LAWN

go LS NE

SOUTH SIDE

LINCOLN PARK

CH ICAG O

AVE

RACINE AVE E

90

CL YB OU RN AV E

Armitage Methodist Church

W DICKENS AVE

W WEBSTER AVE

W BELDEN

ica

WEST SIDE

ASHLAND AVE W FULLERTON AVE

Ch Riv

BERWYN

B

DIVERSEY

E

NORTH SIDE

SKOKIE

90

N

ra

ST DIVISION ST

P A R K

LAKEVIEW AVE

W NORTH AVE

L I N C O L N

W ARMITAGE AVE

McCormick Theological Seminary

PKWY

ST

OAK PARK

AV

N

ST

N

W

OL

RK

SHEFFIELD

AV

DAYTON ST

NC

HALSTEAD

N LI

CLA

0

0

0.25 mi 0.25 km

Fu lle r to n B e ach

Lincoln Park

41

14

SCHILLER ST LASALLE ST

N

41

14

e ak an L hig ic M

er

Thu nder in Chicago’s Lincoln Park

« 25 »