ABC of Impossibility 1937561844, 9781937561840

How does one write an experimental ABC, an impossible theory that would deal with a series of phenomena, concepts, place

207 60 324KB

English Pages 100 [89] Year 2015

Polecaj historie

Table of contents :

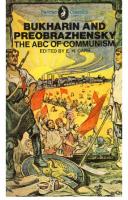

Cover

pharmakon

Title Page

Copyright

ABC of Impossibility

Introduction

Fragments

World

Happiness

Life

Hegel

Tourism

Surfaciality

Indirection

Suicide

New York City

Death

Critchley

Augustine

Poetry

Emptiness

Patti Smith

Relationships

Money I

America

Languor

Marx

Impossibility

Eccentricity

Being

Possibly dolorous tropical lyrical coda

Citation preview

pharmakon

Simon Critchley

ABC OF IMPOSSIBILITY

ABC of Impossibility by Simon Critchley First Edition Minneapolis © 2015, Univocal Publishing Published by Univocal 123 North 3rd Street, #202 Minneapolis, MN 55401 Designed & Printed by Jason Wagner Distributed by the University of Minnesota Press ISBN 9781937561840 Library of Congress Control Number 2015943265

ABC of Impossibility

Introduction

These fragments of an abandoned work largely date from 2004-2006. Around that time, I developed a theory of impossible objects and had the idea for a long book in the form of an ABC. The hope was that the alphabetized entries would deal with a series of phenomena, concepts, places, qualities, sensations, persons and moods in the manner of what one might call ‘para-philosophy’. I began to sketch ideas quite quickly as they came to me and amassed them in a series of dossiers. What I was trying to imagine was a book that was an open-ended series of short chapters, like encyclopedia entries, but of an utterly idiosyncratic kind. As such, the book would move from absurdity to depth, from philosophy to frivolity. What would unify the book and make it mine would be its voice: serious, pathetic, absurd, poetic, cynical, turn and turn about.

3

For reasons that I can’t really recall, I stopped doing this around the end of 2006. Call it a change of life. But I kept looking at some of the entries, much in the manner of picking at scabs, and the idea of a book called ABC of Impossibility stayed with me. So, when Drew Burk was kind enough to invite me to write something experimental, I immediately thought of the book. I am grateful to Univocal for publishing it. The entries are arranged alphabetically on the contents page, but ordered thematically in the book itself, in accordance what I felt to be the best form of counterpoint. I am withholding a number of completed and incomplete fragments because they are too embarrassing, too stupid for words, or too intimate. Maybe, when senility takes over, I will let them go too. Simon Critchley Brooklyn, March 2015.

4

Fragments

A

fter having spent so long, in so many books, during what sometimes seems like somebody else’s lifetime, trying to perfect the art of joined-up writing, I find that the fragment imposes itself on me. This is because I have decided that I want to tell the truth, the truth of a life. For reasons that I hope soon become clear, the truth is only communicable indirectly in fragments. This will be a life in pieces, then. There are various mighty precedents for fragmentary writing, from Pascal and La Rochefoucauld, through to Chamfort who was the inspiration for the early German Romantics, like Friedrich Schlegel, who mastered both the practice and the theory of the fragment and passed on the art to Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and many others. For Schlegel, each fragment was a like a hedgehog, complete in

7

itself and rather prickly, and he believed that the only plausible form for the systematic expression of a philosophy of life was in the little anti-system of a fragment. I propose to take him at his word. I also think of Walt Whitman’s preface to Leaves of Grass where he compares the United States to a poem of fragments and describes democracy as an essentially fragmentary form of social life, where each individual is a fragment in the vast free verse poem that is America. In fact, I think of Whitman a great deal, living just south of where he lived Brooklyn Heights and passing the office of The Brooklyn Eagle on my way home, where Whitman was editor in the 1840s. I imagine him carrying the fragments of Leaves of Grass to his printers in Cranberry Street. As Emerson said, the truth is only available in fragments. I also think of Fernando Pessoa at another Atlantic harbour in Lisbon and his art of the fragment as a way of capturing the disquiet, the desassossego, that is the core of the self. Pessoa pursued this through more than twenty different pessoas, the word means person in Portuguese, in the sense of a mask, actor or dramatis personae. Pessoa called these persons ‘heteronyms’ and his major actors were Alberto Caiero, Alvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis and what he

8

called the ‘semi-heteronym’ of Bernardo Soares, the keeper of books in the city of Lisbon and the author of the Book of Disquiet, Livro do Desassossego. Disquiet can only be expressed directly through the person of another, another pessoa, and only in the form of fragments. In writing this, I promise to tell the truth, but not to be myself. Is disquiet the subject of this book? It is certainly possible. If one were not disquieted, then why would one write? The point is that one’s disquiet, one’s anguish, one’s anxiety, is the essential thing that makes one the one that one is and that it cannot be addressed directly. It can only be faced indirectly, defaced or dressed with someone else’s face. As Pessoa, or Bernardo Soares, puts it in what he describes as his litany, and it is a nicely pagan litany, Nós nunca nos ralizamos. Somos dois abismos – um poço fitando o Céu. We will never be able to realise ourselves, to achieve self-realisation, we are two abysses, a well staring at the sky. The closest we get is indirectly, in a fragment.

9

World

The truth of subjectivity has to be lived apart from the world. Such is the tragic vision of Jansenism and its many heirs, from Kantian moral autonomy in a political kingdom where means are justified by ends, to Levinas’ defense of subjectivity as separation in a world dominated by the political horror of war. There are many other heirs. But how far apart are subjectivity and the world? Here we confront the most acute dialectical paradox of Racine’s Phèdre. If the lesson of Racine’s tragedy is that life in the world is impossible, that the true life transcends the world, then I am still obliged to live in the world. The world is the only reality of which I can be sure and there is no question of a mystical intuition or a higher state

11

of authentic awareness within the tragic vision. I live immanently in a world which is real and of which I can be sure, yet I experience a demand for transcendence that exceeds the world, but also my powers of cognition: the incomprehensible source of the moral law in Kant, the transcendent ethical demand of the other in Levinas. Hence the need, in Pascal, for the wager, which is not some intellectual game for a sceptical, urbane, seventeenth-century audience, but is rather the best bet of that which I cannot be sure. The tragic vision is a refusal of the world from within the world, as Lucien Goldmann writes, “Tragic man is absent and present in the world at one and the same time, exactly as God is simultaneously absent and present to man.” The human being, like Phaedra, is a paradox: we are ineluctably in the world, but we are not of the world. That is, we are not what we are in. Such is the curse of reflection. We are confronted with a world of things, but we are not at one with those things, and that experience of not-at-one-ness with the world is the experience of thinking. In other words, the human being is an eccentric creature, an oddity in the universe. Such eccentricity might be described as tragic, but it might be even better approached as comic.

12

Without God, the drama of Racine’s Phèdre is reduced to being some story about a crazy woman trying to commit incest at court. We have to believe that Racine believed. Yet, what if we do not believe what he believed? What if we want to accept a tragic vision without God? Can that thought really be endured? Can it? Really? We will have to find out for ourselves

13

Happiness

What is happiness? As I teach philosophy for a living, let me begin with a philosophical answer. For the philosophers of Antiquity, notably Aristotle, it was assumed that the goal of the philosophical life — the good life, moreover — was happiness and that the latter could be defined as the bios theoretikos, the solitary life of contemplation. Today, few people would seem to subscribe to this view. Our lives are filled with the endless distractions of cell phones, car alarms, commuter woes and the traffic in Bangalore. The rhythm of modern life is punctuated by beeps, bleeps and a generalized attention deficit disorder. But is the idea of happiness as an experience of contemplation really so ridiculous? Might there not be something in it? I am reminded of the following extraordinary passage from Rousseau’s final book and

15

his third (count them) autobiography, Reveries of a Solitary Walker, If there is a state where the soul can find a resting-place secure enough to establish itself and concentrate its entire being there, with no need to remember the past or reach into the future, where time is nothing to it, where the present runs on indefinitely but this duration goes unnoticed, with no sign of the passing of time, and no other feeling of deprivation or enjoyment, pleasure or pain, desire or fear than the simple feeling of existence, a feeling that fills our soul entirely, as long as this state lasts, we can call ourselves happy, not with a poor, incomplete and relative happiness such as we find in the pleasures of life, but with a sufficient, complete and perfect happiness which leaves no emptiness to be filled in the soul. (emphases mine) This is as close to a description of happiness as I can imagine. Rousseau is describing the experience of floating in a little rowing boat on the Lake of Bienne close to Neuchâtel in his native Switzerland. He particularly loved visiting the Île Saint Pierre, where he used to enjoy going for exploratory walks when the weather was fine and he could indulge in the great

16

passion of his last years: botany. He would walk with a copy of Linneaus under his arm, happily identifying plants in areas of the deserted island that he had divided for this purpose into small squares. On the way to the island, he would pull in the oars and just let the boat drift where it wished, for hours at a time. Rousseau would lie down in the boat and plunge into a deep reverie. How does one describe the experience of reverie: one is awake, but half asleep, thinking, but not in an instrumental, calculative or ordered way, simply letting the thoughts happen, as they will. Happiness is not quantitative or measurable and it is not the object of any science, old or new. It cannot be gleaned from empirical surveys or programmed into individuals through a combination of behavioral therapy and anti-depressants. If it consists in anything, then I think that happiness is this feeling of existence, this sentiment of momentary selfsufficiency that is bound up with the experience of time. Look at what Rousseau writes above: floating in a boat in fine weather, lying down with one’s eyes open to the clouds and birds or closed in reverie, one feels neither the pull of the past nor does one

17

reach into the future. Time is nothing, or rather time is nothing but the experience of the present through which one passes without hurry, but without regret. As Wittgenstein writes in what must be the most intriguing remark in the Tractatus, ‘the eternal life is given to those who live in the present’. Or, as Whitman writes in Leaves of Grass, ‘Happiness is not in another place, but in this place … not for another hour … but this hour’. Rousseau asks, ‘What is the source of our happiness in such a state?’ He answers that it is nothing external to us and nothing apart from our own existence. However frenetic our environment, such a feeling of existence can be achieved. He then goes on – amazingly – to conclude, ‘as long as this state lasts we are self-sufficient like God’. God-like, then. To which one might reply: Who? Me? Us? Like God? Dare we? But think about it: If anyone is happy, then one imagines that God is pretty happy, and to be happy is to be like God. But consider what this means, for it might not be as ludicrous, hybristic or heretical as one might imagine. To be like God is to be without time, or rather in time with no concern for time, free of the passions and troubles of the soul, experiencing something like calm in the face of things and of oneself.

18

Why should happiness be bound up with the presence and movement of water? This is the case for Rousseau and I must confess that if I think back over those experiences of blissful reverie that are close to what Rousseau is describing then it is often in proximity to water, although usually saltwater rather than fresh. For me, it is not so much the stillness of a lake (I tend to see lakes as decaffeinated seas), but rather the never-ending drone of the surf, sitting by the sea in fair weather or foul and feeling time disappear into tide, into the endless pendulum of the tidal range. At moments like this, one can sink into deep reverie, a motionlessness that is not sleep, but where one is somehow held by the sound of the surf, lulled by the tidal movement. Is all happiness solitary? Of course not. But one can be happy alone and this might even be the key to being happy with others. Wordsworth wandered lonely as a cloud when walking with his sister. However, I think that one can also experience this feeling of existence in the experience of love, in being intimate with one’s lover, feeling the world close around one, where time slips away in its passing. Rousseau’s rowing boat becomes the lovers’ bed and one bids the world farewell as one slides into the shared selfishness of intimacy.

19

… And then it is over. Time passes, the reverie ends and the feeling for existence fades. The cell phone rings, the email beeps and one is sucked back into the world’s relentless hum and our accompanying anxiety.

20

Life

Life is movement. It is the feeling of movement or what the Greeks called kinesis whose counter-thrust is lethargy, the slowing down of existence into a lassitude and languor. But life as movement can be the sheer restlessness of anxiety, the shape of a becoming that is too tightly bound to its terminus in death, a death that casts too long a shadow over life. Living in death’s shadow grants both individuality and morbidity, individuality as morbidity. The trick, if it is a trick, is to dwell between movement and lethargy, to try and balance at the mid-point between them. This is very difficult. It means learning to become a tightrope walker. I have a terrible sense of balance.

21

Hegel

In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel writes, ‘No people ever suffered wrong. What it suffered, it merited’. This is wrong. Hegel’s idea is that suffering is justified historically. That is, suffering is suffering for the sake of world history, for the sake of what he sees as Spirit’s relentless forward movement, that culminates in the Germany of the early 19th Century or in the Fukuyama-esque delusions of the so-called ‘New American Century’ into which we have slowly crawled. Such is the secular theodicy of Hegelianism and related progressivist conceptions of history. This is what Hegel means when he speaks gnomically at the end of the Phenomenology of Spirit of ‘the Calvary of Absolute Spirit’. Calvary is Golgotha, a field of skulls. History is a field of skulls, a

23

cemetery. There’s no denying it. But is it the case that, as Aeschylus’ characters repeat in the Oresteia, we suffer into truth, and that such truth finds expression in the world we inhabit? Such is perhaps the truth of tragedy and arguably the truth of Hegelian dialectics. But in saying this most of the world’s inhabitants, both human and animal, are condemned to suffer in falsehood. Life is not tragic, it is ridiculous and it is best not conveyed in a philosophical system or a tragic trilogy, but in a joke, a paradox, a fragment.

24

Tourism

Heidegger once said, ‘tourism should be banned’. The more I travel, the more I agree with him, particularly when I visit Germany.

25

Surfaciality

The poet issues reminders for what we already know and interprets what we already understand but have not made explicit. Poetry takes things as they are and as they are understood by us, but in a way that we have covered over through force of habit, a contempt born of familiarity, or what Fernando Pessoa’s heteronym Alberto Caeiro calls ‘a sickness of the eyes’. Poetry returns us to our familiarity with things through the de-familiarization of poetic saying, it provides what Caeiro calls ‘lessons in unlearning’ where we finally see what is under our noses. What the poet discovers is what we knew already, but had covered up: the world in its plain simplicity and palpable presence. In this way, we can perhaps reach lucidity. But this lucidity is not a propositional explicitness, it is not the cognitive awareness that ‘water is everywhere and at all times two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen’, or that ‘Benjamin

27

Franklin was the inventor of the lightning rod’. It is rather a lucidity at the level of feeling of what Heidegger calls mood (Stimmung) that the poetic word articulates without making cognitively explicit, as when Pessoa writes in a text on sensationism, ‘Lucidity should only reach the threshold of the soul. In the very antechambers of feeling it is forbidden to be explicit’. Poetry produces felt variations in the appearances of things that return us to the understanding of things that we endlessly pass over in our desire for knowledge. Poetry, in the broad sense of Dichtung or creation is the disclosure of existence, the difficult bringing to appearance of the fact that things exist. By listening to the poet’s words, we are drawn outside and beyond ourselves to a condition of being there with things where they do not stand over against us as objects, but where we stand with those things in an experience of what I like to call, with a nod to Rilke, openedness, a being open to things, an interpretation which is always already an understanding (hence the past tense) in the surfacial space of disclosure. If this sounds a little mystical, then I’d like to say with Caeiro, ‘está bem, tenho-o’ ‘that’s fine, I have it’. If there is a mystery to things, then it is not at all other-worldly, or some mysticism of the hidden.

28

On the contrary, the mystery of things is utterly of this world and the labour of the poet consists in the difficult elaboration of the space of existence, the openedness within which we stand. Of course, one might respond that Caeiro is simply replacing one kind of mysticism with another: that is, rejecting an other-worldly mysticism of the transcendent beyond with the here-and-now mysticism of immanent presence. To which Caeiro might also say, ‘está bem’; his would be a mysticism of the bodily presence of things to the senses. The contrast is between what we might calls a mysticism of gnosis that claims to see beyond appearances to their invisible source of meaning and an agnostic mysticism that just sees appearance. Caeiro does not claim to know anything about nature; he simply sings what he sees, Se quiserem que eu tenha um misticismo, está bem, tenho-o. Sou místico, mas só com o corpo. A minha alma é simples e não pensa. O meu misticismo é não querer saber. É viver e não pensar nisso.

29

Não sei o que é a Natureza: canto-a. Vivo no cimo dum outeiro Numa casa caiada e sozinha, E essa é a minha definição. If you’d like me to have a mysticism, that’s fine, I have it. I’m a mystic, but only with the body. My soul is simple and doesn’t think. My mysticism is not wanting to know. It is to live and not to think about this. I don’t know what nature is: I sing it. I live in the top of a small hill In a whitewashed and solitary house, And this is my definition. For Caeiro, we need an apprenticeship in unlearning in order to learn to see and not to think. We need to learn to see appearances and nothing more, and to see those appearances not as the appearances of some deeper, but veiled reality, but as real appearances. Of course, it is often hugely difficult to even see those appearances as our vision becomes obscured by habit, by what Pascal called the machine. Such machinic habit is what Caeiro calls the ‘sickness of the eyes’ that happens when we think and

30

do not see, ‘Pensar é estar doente dos olhos’.(II 207) In our sickness, we pass over what is most obvious, most familiar and closest to us, namely the phenomenon of the world, the fact that things simply are, in their plain, palpable and everyday presence. What Caeiro counsels, and one finds similar advice in Wallace Stevens, is that we give up both the skeptical and metaphysical impulses that are distrustful of the world of appearances. If we follow the path of Caeiro’s lessons in unlearning, then what we might learn to cultivate is the art of surfaces, the prose of things that surround us, those things that escape our attention because of their sheer obviousness, because they are under our noses.

31

Indirection

What is closer to me than myself? Nothing. Yet, how does one say this? How to express this closeness as closeness, i.e., closely? It is enormously difficult, as when Heidegger says that what is closest to me in everyday life is furthest from being understood, where he quotes Augustine saying that I have become to myself a terra difficultatis, a land of toil where I labour and sweat. It seems to me that the only way of expressing the closeness of self to itself is indirectly, through other voices and personae, Pessoa’s heteronyms. These heteronyms are the names of strangers, they are ways of estranging the self so as to approach it, to approximate it, in closeness. This closeness to self and to world and of self to world is so close that one cannot separate them, divide and sunder them. Self and world are of a piece. They are one piece of a garment that should not be broken down into pieces like mind and reality or subject and

33

object. They are the one piece of which I am made and which I have made. The world is what you make of it. That is to say, self and world are a fiction, a fiction that we take to be true and in which we have faith. The difficulty is making that faith explicit. (A group of wealthy, noisy, pink English tourists are sitting behind me at the beach restaurant as I write. Endless chattering is interspersed with vulgar, horselike embarrassed laughter. ‘Why don’t these fuckers just die?’, I think to myself. Their behaviour is like some grotesque act to me, as sphincter-tightening as Joyce’s Irish Sea, which is where I would like to drown them. People tight as a drum with no sense of rhythm.) To return to indirection: all one can try and do in a book is to tell the truth. One can only do this in a fiction, by putting on a mask, by naming oneself with a heteronym. If truth is a fiction, or truth has to be related in a fiction because it cannot be articulated directly, then this raises the question: is there a supreme fiction, a fiction in which we could believe, where it is a question of final faith in final fact? Wallace Stevens insists that ‘it is possible, possible, possible. It must be possible’, where it is at the very least unclear whether the repetition of the word ‘possible’ is a symptom of strength or weakness. It

34

is telling that a poet of the supreme caliber of Stevens only felt that he could write ‘Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction’.

35

Suicide

Have you ever felt your body losing control in the sea, being swept by the swell, pulled powerless, pulled out, pulled under? When it happened to me it made my loins tingle in the same way as when I am close to the edge of a tall building I desire more than anything else to throw myself off. I see myself flying through the air – joyous in that instant – and then bang! I stayed in Tom’s apartment in London for a month one summer. He lived on the thirteenth floor of a tower block on a quasi-council estate with stunning views of central London, and a panorama stretching from Highgate in the north to Clapham in the south and taking in everything in between. All I thought about for that month was launching myself from his tiny terrace. It wasn’t that I felt unhappy. On the

37

contrary, I simply wanted to feel the fullness of that loin-tingling instant as my body fell to earth out of control. Perhaps I should learn to ski instead.

38

New York City

David is an anarchist anthropologist, and it is to him that I owe the true story of Gotham. It was a small village in south Nottinghamshire in England which, during the reign of bad King John in the early 13th Century, decided to forgo the questionable pleasure and huge expense of welcoming the King and his considerable retenue. Instead, they decided to behave like idiots. It is reported that royal messengers found the villagers engaged in ridiculous tasks, like trying to drown an eel or joining hands around a thornbush to shut in a cuckoo. King John took fright and moved on. This story of Gotham as a village of idiots full of would-be village idiots, burbled down through history until Washington Irving picked up the legend as an appellation for New York in the early 19th Century and the name stuck, right through to Batman and beyond. It is also the name of a chic little restaurant on Manhattan’s West 12th Street,

39

between 5th Avenue and University Place, which offers an excellent and reasonably priced lunch menu, despite being full of idiots. New York is a city of idiots, a town full of crazies, some of them on medication, some of them exploring their inner truth, some of them doing both at once. One or two New Yorkers still try to scare the king. But the idiocy of New York also has another deeper dimension evoked at the beginning of E.B. White’s wonderfully tightly written memoir, Here is New York. ‘On any person who desires such queer prizes’, he begins, ‘New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy’. Of course, this is deeply paradoxical, but completely accurate in my view. The prize of life in New York is the only privacy that is worthwhile, one that is not lived sequestered behind walls but lived in the crowded exposure of the public realm, on the subway or on the street. The loneliness of which White speaks is utterly foreign to a feeling of alienation or anomie; it is the gift of idiocy. In the many idioms of New York life, idiosyncrasy and individuality can meld together. Provided, of course, that one is lucky. But, as White adds, no one should come to live in New York unless she is prepared to be lucky. The idiocy of New York can forge the strongest individuals, but it can also destroy them and drive them mad.

40

Death

Philosophy begins with the exemplary death of Socrates. Much subsequent philosophy has been concerned, obsessed even, with the idea of dying well, or dying well as the consequence of living well. Cicero writes, in words that echo down the tradition through Montaigne to Heidegger, that ‘to philosophize is to learn how to die’. One imagines the portly David Hume dying a lucid and happy atheist until the end. However, the history of philosophers’ deaths is also a tale of madness, suicide, unhappiness, banality, bad luck, and some dark humour. One thinks of Descartes’ death by pneumonia after early morning tutorials in chilly Stockholm with Queen Christina, Nietzsche’s soft-brained babbling descent into oblivion, Roland Barthes hit by a laundry truck, Deleuze defenestrating himself while listening to a David

41

Bowie album, Foucault dying of AIDS, MerleauPonty discovered dead in his office with his face in a book by Descartes, Derrida dying of the exactly the same disease and at the same age as his father, or of my teacher Dominique Janicaud dying alone on a beach outside Nice after suffering a heart attack while swimming. I would like my own view of death to be closer to Epicurus and what is known as ‘the four-part cure’: don’t fear God, don’t worry about death, what is good is easy to get and what is terrible is easy to endure. The problem with this position is that it fails to provide a cure to that which affects us most powerfully and what is so difficult to endure with mortality: not our own death, but the death of those we love. It is the deaths of those we are bound to through love that undo us, that unstitch our carefully tailored suit of the self, that unmake whatever meaning we have made. It is in mourning and grief that we most become ourselves, when we acknowledge that part of our selves that we have lost and which we will forever have lost.

42

Critchley

Here I am, struggling to make sense at the University of the West Indies, in Barbados, speaking about some book of mine that the people who invited me wanted to discuss. I am doing my best, which is not that good. I am asked a question, a rather long and ponderous question about the relation of my work to Christianity. Inwardly, I sigh. The man who asks the question is then introduced as Dean Critchley, a black Barbadian. I begin to dissolve inwardly. Critchley is obviously this man’s slave name. Now, Critchley is a place name, and a relatively small place name, from Lancashire, the corner of some hamlet between Bolton and Preston. It is therefore highly likely that one of my ancestors or near ancestors was a plantation owner or some minion in Barbados. The room begins to fill with blood.

43

Augustine

In Book 8 of the Confessions, Augustine describes himself as ‘still tightly bound by the love of women’, which he describes as his ‘old will’, his carnal desire. This will conflicts with his ‘new will’, namely his spiritual desire to turn to God. Alluding to and extending St Paul’s line of thought in Romans, Augustine describes himself as having ‘two wills’, the law of sin in the flesh and the law of spirit turned towards God. Paralyzed by this conflict and unable to commit himself completely to God, these two wills lay waste to Augustine’s soul. He waits, hesitates, and hates himself. Seeing himself from outside himself, from the standpoint of God, Augustine is brought face-to-face with his self and sees how foul he is, ‘how covered with stains and sores’. He continues, ‘I looked, and I was filled with horror, but there was no place for me to flee away from myself’.

45

Such is the fatal circuit of what Michel Foucault calls the Christian hermeneutics of desire opposed to the pagan aesthetics of existence. In a seminar at New York University in 1980, Foucault is reported to have said that the difference between late antiquity and early Christianity might be reduced to the following questions: the patrician pagan asks, “Given that I am who I am, whom can I fuck?” The Christian asks, “Given that I can fuck no one, who am I?” Foucault’s insight is profound, but let me state categorically and without a trace of irony that, as a committed atheist, I side with the deep hermeneutics of Christian subjectivity against the superficial pagan aesthetics of existence. The question of the being of being human – who am I? – that begins with Paul and is profoundly deepened by Augustine arises in the sight of God. The problem is how that question survives God’s death. This is Rousseau’s question in his Confessions, it is Nietzsche’s question in Ecce Homo, and it is Heidegger’s question in Being and Time. In my less humble moments, I think of it as my question as well. Whether or not he exists, we are slaves to God.

46

Poetry

‘Poems aren’t pies, we aren’t herring’. – Danill Kharms

47

Emptiness

What is it about the experience of emptiness, about turning your back on the world and facing nothing? For me, this happens in front of the sea, each time I face the brightness over the sea. One looks at the sea and feels an emptiness. Facing the sea is absence regarded. It evokes a feeling that I want to call calm. The body slows and the mind lays by its trouble and adapts itself to the rhythm of the waves, where time is tide, and tide is endless to and fro, coming and going. Time becomes a circle rather than a line, a cycle endlessly renewed rather than a movement of decline or deadlines. At times like this, I begin to think. To be honest, I don’t know what goes on in my head much of the rest of the time, or what to call what goes on in my head, but it is not thinking. Facing the emptiness

49

of the sea, one begins to think: slowly and with a deliberate carelessness. Cities sometimes slip into the sea, eaten alive by their thoughtfulness, like Dunwich on the Suffolk coast in East Anglia. Or the sea slips away from them, in some act of historical thoughtlessness, where tides’ time thickens into silt. Harbours get blocked with silt and clogged with mud, becoming unnavigable. The land seems to rise like the wooden top of an old school desk and the cities slip back into an inkwell of obscurity, like Ephesus and Miletos on the Ionian coast in Turkey or Istria at the mouth of the Danube. Other cities are destroyed by a vindictive violence that is the enemy of thought like Carthage, ravaged brick by brick with godless Roman arrogance. Silt sometimes slows the water, allowing malarial swamps to form, like Torcello in the Venetian lagoon, the proto-Venice with its rubble in the marshes and a few lonely Byzantine mosaics. I sometimes dream of writing a volume on the role of silt in determining the shape of world history and I imagine whole chapters on lagoons and blocked harbours and subsections on ox-bow lakes and alluvial deposits.

50

I have, for as long as I can remember, been obsessed with cities prior to their settlement or at the moment of settlement. I like to think of what opposed sets of eyes were seeing and minds thinking as white sails were spotted on the horizon at what would become Jamestown or Botany Bay or off the coast of the treed vastness that would become Brazil. I think of vicious settlers, happily decimating the local populations and of the broken Jesuits who landed in Brazil with the text of a Papal bull declaring that they must save the souls of the natives. I think, repeatedly, of the first European feet to tread on Manhattan, on this hilly, handsome island situated on a huge river beckoning possible passage to the Indies. I try and think about the places I know at a point approaching emptiness and therefore, I suppose, thoughtfulness. Emptiness – this is how the earth will be after humans have finished with it, or – more likely – it has finished with them.

51

Patti Smith

I remember walking with my son in Bunhill Fields cemetery, EC1, just on the edge of the City in London. I had promised to show him the grave of William Blake, not that he knew who Blake was or cared very much at the time. I remember telling him that there were always fresh flowers on the grave. It also just so happened to be on the way to Liverpool Street station where we could get the train to Colchester. Yet, as we approached Blake’s grave, facing the taller and much more imposing grave of Daniel Defoe, I saw a small group of people, one of them carrying a camera and another slight figure, wearing shades. ‘That’s Patti Smith’, I said to Edward. ‘Who’s that?’ he said. At that point, Patti Smith and I glanced at each other, perhaps we didn’t. It was difficult to see in the sharp sunlight. She was wearing huge shades. I spent the rest of the walk trying to render various

53

tracks from ‘Horses’. It is difficult to impress one’s children. Funny pairing, Defoe and Blake. Could there be an odder couple in the history of English literature than the transmogrifying spirit-seer and the plodding literalist? But they were both London boys and near neighbours in life, living close to the Dunciadical shame that was 18th Century Grub Street. Even odder, James Joyce, whose literary criticism bears strange comparison with his fiction, lectured on Blake and Defoe in Trieste in 1912 and saw them as the two key figures in the emergence of English literature.

54

Relationships

Sometimes, the more words that are used, the less they mean, until language becomes abusive, injurious and violent. At such moments, one circles around a tight knot of mutual unintelligibility that cannot be cut. Is there some truth that is revealed when lovers argue? No. Arguing is to a relationship what masturbation is to sex.

55

Money I

What is money? Many things. It is, of course, the coins and notes rattling in our pockets, as well as the piles of real and virtual stuff lying in banks, or the smart money that tends towards disappearance and increasing immateriality, being shuffled electronically along the vectors of the financial networks. This might serve as an empirical definition, but what is the logic of the concept of money? The core of money is trust and promise, ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of …’ on the British Pound, the ‘In God we trust’ of the US Dollar, the BCE-ECB-EZB-EKT-EKP of the European Central Bank that runs like a Franco-Anglo-GermanoGreco-Finno-Joycean cipher across the top of every Euro note. In other words, the legitimacy of money is based on a sovereign act, or a sovereign guarantee that the money is good, that it is not counterfeit.

57

Money has a promissory structure, with an entirely self-referential logic: the money promises that the money is good; the acceptance of the promise is the acceptance of a specific monetary ethos, a specific, yet often flexible monetary geography. This ethos, this circular ‘money promising that the money is good’ is underwritten by sovereign power as its transcendent guarantee. It is essential that we believe in this power, that the sovereign power of the bank inspires belief, that the ‘Fed’ has ‘cred’ as it were. Credit can only operate on the basis of credence and credibility, of an act of fidelity and faith, of con-fid-ence. The transcendent core of money is an act of faith, of belief. One can even speak of a sort of monetary civil religion or patriotism, which is particularly evident in attitudes in the US to the Dollar, particularly to the sheer materiality of the bill, and in the UK’s opposition to the Euro and to the strange cultural need for money marked with the Queen’s head. In a deep sense, money is not. It exists empirically, but it is not essentially there at all. All money is what the French call escroquerie, swindling, it is a virtual or at best conceptual object. It is, in the strictest Platonic definitional sense, a simulacrum, something that materializes an absence, an image for something

58

that doesn’t exist. Money is delusionary and faith in money is a kind of collective psychosis. In the godless wasteland of global capitalism, money is our only metaphysics, the only transcendent substance in which we truly must have faith. It is this faith that we celebrate, we venerate, in commodity fetishism. Adorno makes the point powerfully, ‘Marx defines the fetish-character of the commodity as the veneration of the thing made by oneself which, as exchange value, simultaneously alienates itself from producer to consumer…. This is the real secret of success. It is the mere reflection of what one pays in the market for the product. The consumer is really worshipping the money that he himself has paid for the ticket to the Toscanini concert. He has literally ‘made’ the success which he reifies and accepts as an objective criterion, without recognising himself in it. But he has not ‘made’ it by liking the concert, but rather by buying the ticket.’ It is a commonplace misunderstanding of capitalism to declare that its materialism consists in a voracious desire for things. It is rather that we love the money that enables us to buy those things for it reaffirms

59

our faith and restores the only metaphysical basis for our trust in the world. For us, here and now, money has no outside, there is no pure form of economy, no barter system, somehow unsullied by money’s circulation. You are always already locked into a monetary ethos, part of a contour line upon a financial cartography. There is only the sully of money. All money is dirty. From a Freudian perspective, money is deeply anal, it is shit rather than bread, you can use it to buy shit, and a general obsession with money is perhaps why people talk so much shit. For the infant, the little Freudian child, shit is money, which is why it is so proud of its soft, smelly currency. In the protoLockean world of anal-sadism, shit is the first form of property ownership; the labour theory of value begins in your diapers. Let’s not forget, Freud is a kind of anti-Midas: where, for Midas, everything natural was transformed into gold, for Freud, all that glitters is transformed into shit. Freud touches a familiar object and suddenly – poo! – one wonders where the smell is coming from. My favourite Freudian neurotic, the Rat Man, is obsessed with money, with repaying a misconceived debt. He is also highly aware of money’s dirtiness, and anally obsessed: his fears of Rat-torture (in which a rat eats into one’s anus) being verbally linked to shame about his ‘Spielratte’, his

60

father’s gambling debts. His very neurosis is described in economic terms by Freud, who writes, ‘In his obsessional deliria he had coined himself a regular rat currency. Little by little he translated into this language the whole complex of money-interests which centred around his father’s legacy to him.’ Of course, money is also indexed to desire, and there is a strong association between money and sex. Money is power, sex is power, power is sexy and so is money. And let’s not forget the profound link between psychoanalysis and payment. Were there ever creatures on earth more obsessed with money than psychoanalysts? Of course, they are right and the core of the psychoanalytic pact is a monetary union, a monetary act of trust: one has to pay, whatever it is that you can afford, otherwise the analysis begins to lose credibility. One must not do therapy for free. The faith and trust of the relation between patient and analyst, what Freud called ‘transference’, which is the key to any potentially successful therapy, is guaranteed by money; the promissory trust of therapy is secured through monetary exchange.

61

America

I remember my first trip to America, the continent and not just the country. It was in 1991, I was 31 years old. Flying, eyes wide shut, somewhat bewildered, from St Louis to Memphis, I was reading Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, the opening pages to be precise where he famously declares, ‘In the beginning, all the world was America’. I glanced out of the window at the forested vastness of the undulating landscape beneath me, which still looked to my eyes like some state of nature. This big, strange country will always be defined for me by that original Lockeian act of violent settlement and the viral spread of private property. In the few centuries that have passed since the original act of expropriation, nothing negates for me the sheer contingency of life here, the layering of a savage domesticity over a vast and alien nature.

63

Languor

Consider the character of Phaedra in Racine’s extraordinary eponymous 1677 tragedy, “the masterpiece of the human mind,” as Voltaire declared. Phaedra was the daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, and granddaughter of Pasiphaë’s father, the Sungod or Helios, whose light burns Phaedra’s eyes and whose scorching gaze she cannot bear, but from whom she cannot hide. The Sun watches her throughout the play: silent, remote to the point of absence, but of piercing intensity, like the Deus absconditus of Jansenism. Her father was King of Crete and later judge in Hades. She married Theseus, King of Athens, who brought her back to Greece after slaying the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth. Aphrodite, as she is wont, inflamed Pasiphaë with a monstrous passion for a bull. Daedalus, the artificer, made a hollow wooden cow where Pasiphaë could crouch to be fucked by the bull. From this

65

union was born the Minotaur. It is the overwhelming power of her mother’s predestined passion that now flows through Phaedra’s veins. Venus is in Phaedra’s blood: it flows through her like a virus, the sickness of illicit erotic desire. With Theseus away for over six months on one of his adventures, she burns with passion for Hippolytus, Theseus’s virginal son and her stepson. When Phaedra first saw Hippolytus, she declared, “darkness drenched my eyes.” She languishes in dark desire, Venus clawing at her heart, her mother’s sin boiling in her blood. Worn down by the guilt of this passion, and the division it creates within her, she resolves to die. This is how we first encounter her in the play, dragging herself into the light to greet her grandfather, the Sungod, for the last time, “Soleil, je te viens voir pour la dernière fois.” There is a whole metaphysics of blood at work in the Racine’s tragedy: blood is the existential mark of the past, of one’s bindedness to a past that you might think you are through with, but which is not through with you. Contaminated by the virus of Venus that flows in her veins, Phaedra cannot exist in the present, let alone envisage the future. Rather, she is a prisoner of her past, the burned-in memory of her mother’s monstrous desire and her

66

grandfather’s conscience. Phaedra’s present continually lags behind itself. She cannot make up her time. She is always too late to meet her fate and this is why she is so utterly fatigued. The horror of being riveted to what Heidegger would calls one’s facticity injects a fearful languor into Phaedra’s limbs. The virus of Venus that flows in her blood weighs her down. She writhes, she burns. Her body possesses or is possessed by an unbearable gravity that pulls her earthwards. Languor is her affective response to the exitlessness of existence, to the fact of being chained to herself. The experience of languor is a bodily response to facticity, of the body being coursed through by a desire that is felt as alien, the virus of Venus in the veins. This desire overtakes me and slows me down, inducing a languid sluggishness, a lethargy, a creeping inertia, a sort of Trägheit—which is Freud’s word for describing the death-drive, that cosmic-sounding force that provides a compelling analogue to the world of Phaedra’s experience. Languor makes me an enigma to myself. I find myself enchained to a facticity whose very nearness makes me lose focus and unable to catch my breath. I burn, breathless, in my languor. This experience is wonderfully described by Augustine in Confessions,

67

book 10, where he is agonizing about the virtue involved in the sensual pleasure of religious music. He writes, and think here of Phaedra’s sense of being watched by God, “But do you, O Lord my God, graciously hear me, and turn your gaze upon me, and see me, and have mercy upon me, and heal me. For in your sight I have become a question to myself and that is my languor (mihi quaestio factus sum et ipse est languor meus”. Augustine’s words are cited here in Jean-François Lyotard’s remarkable, and remarkably obscure, posthumously published La confession d’Augustin, an extremely Christian text for such an apparent pagan. My languor is the question that I have become for myself in relation to the presentabsent Deus absconditus who watches me, who may heal and have mercy upon me, but whom I cannot know and whose grace cannot be guaranteed. The questions I pose to God make me a question to myself. Lyotard adds, gnomically, “Lagaros, languid, bespeaks in Greek a humor of limpness, a disposition to: what’s the point? Gesture relaxes therein. My life, this is it: distentio, letting go, stretching out. Duration turns limp, it is its nature”. The experience of languor, for Lyotard, is both the body’s limpness, its languid quality, and time as distension, as stretching out, procrastination. In languor, I suffer from a delay with respect to myself,

68

my suffering is experienced as what Lyotard calls, in language reminiscent of Blanchot, “waiting”: “The Confessions are written under the temporal sign of waiting”. Originally inauthentic, the weight of the past makes me wait, and awaiting, I languish. I grow old, I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled. I am filled with longing. Lyotard, close to dying as he is writing, quotes the above passage from Augustine for a second time, and adds, “[I]pse est languor meus. Here lies the whole advantage of faith: to become an enigma to oneself, to grow old, hoping for the solution, the resolution from the Other. Have mercy upon me, Yahweh, for I am languishing. Heal me, for my bones are worn”. Phaedra languishes. In an existence without exit, time stretches out and she waits for an end that will not come. She experiences languor as a mental and physical weariness, a sheer fatigue in the face of her thrownness. But her languor also has strong erotic overtones: it is a feeling of dreaminess and laxity, closer to the Middle English “love-longing” and the German Sehnsucht, yearning. This is the sort of eroticized sickness that afflicts Troppmann, the hero of Georges Bataille’s Le bleu du ciel, languishing in his disgrace and burning with hallucinatory sexual desire and thoughts of his own death. The book begins, “I know. I’m going to die in disgraceful circumstances.”

69

Phaedra’s malaise is the experience of languor as an affective response to the fact of being riveted to herself. Guiltily bound to the fire of Venus that burns in her blood with the distant Sungod watching impassively, she languishes sensuously in this captivity. Life is a trance for Phaedra, a sort of agonized fainting away that produces moments of erotic stupefaction where she is hypnotized by the desire that she loathes.

70

Marx

When I think of Marx, what comes to mind is not the iconic and huge-bearded impoverished titan working heroically in the British Library Reading Room and writing below his best for the American press in order to feed his wife and kids. Rather, I think of the youthful Karl Heinrich studying in Berlin and writing sonnets to his unwell love Jenny von Westphalen, ‘Love is Jenny, Jenny is love’s name’, he wrote; she called him ‘my little wild boar’. Or I think of him in his room sketching the first act of his pretty awful tragedy, Oulanem, or arranging the chapters of a sub-Sternean humoristical novel called Scorpion and Felix, complete with sub-Shakesperean puns (‘A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!’, said Richard III. ‘A husband, a husband, myself for a husband’, said Grethe), and extended jokes about constipation,

71

‘Grethe! How many days is it since Boniface last had a motion? Did I not instruct you to administer to him a lavement at least once every week? But I see that in future I shall have to take over such weighty matters myself! Bring oil, salt, bran, honey and a clyster! ‘Poor Boniface! You are constipated with your hollow thoughts and reflections, since you can no longer relieve yourself in speech and writing! ‘O admirable victim of profundity! O pious constipation!’

72

Impossibility

About ten years ago, I began to develop a theory of impossible objects. That is, objects, things, substances and places about which I had an obsessive relation. The three objects concepts picked out at that time for special treatment were poetry, humour and music and I have tried to write about these in various books and talks over the years. What unified my relation to these objects was the fact that whatever I said about these things would not, in principle, succeed in pinning them down, defining or appropriating them: do we need a philosopher to explain why we laugh before we find things funny? Of course not. Ditto for poetry and music. Having established this taste for impossibility and my own philosophical redundancy, I have decided to expand its field to try and catalogue those impossible objects in no particular order, other than that with which they force themselves on my mind. These fragments

73

are a collection of ladders that can be kicked away in order to look directly at those things of which it is not possible to speak.

74

Eccentricity

There is an enduring, classical assumption that the animal is its body. I simply don’t know whether this is true. Wittgenstein writes that, if a lion could speak then we could not understand him. Which probably shows that Wittgenstein didn’t spend much time in the company of lions. Yet, when a parrot does speak then we assume that he does not understand himself. But who knows? Whatever the truth of the matter with animals, in my view human beings are essentially eccentric, that is, we have an eccentric position with regard to nature. This thought can be confirmed by the fact that not only are we our bodies, we also have our bodies. That is, the human being can subjectively distance itself from its body, and assume some sort of critical position with respect to itself. This is most obviously the case in the experience of illness, where one

75

might say that in pain we all try and turn ourselves into Cartesian mind/body dualists. In pain, I attempt to take a distance from my body, externalise the discomfort and insulate myself in thought, something which occurs most obviously when we lie anxiously prone in the dentist’s chair. But more generally, there are a whole range of experiences, most disturbingly in anorexia, where the body that I am becomes the body that I have, the body-subject becomes an object for me, which confirms both the possibility of taking up a critical position, and also underlines my alienation from the world and nature. Yet, the curious thing about such experiences is that if I can distance myself from my body, where being becomes having and subject becomes object, then can I ever overcome that distance? If, the moment that reflection begins, I become a stranger to myself, a foreign land, then can I simply return home to unreflective familiarity? Might one not conjecture that human beings, as eccentric animals, are defined by this continual failure to coincide with themselves? Does not our identity precisely consist in a lack of self-identity, in the fact that identity is always a question for us – a quest, indeed – that we might vigorously pursue, but it is not something I actually possess? As Plessner says, ‘Ich bin, aber ich habe mich nicht’. I most certainly am, but yet I do not have myself.

76

Incidentally, I think this is the truth of satire, which does at least two things: it engages in a strategy of bathos or philosophical ‘descendentalism’ (the word is Thomas Carlyle’s) as opposed to the somber transcendentalism of an Emerson or a Coleridge. Satire deflates pomposity and ridicules the seemingly august, elevated and noble. It reveals the depth of our moral hypocrisy. Secondly, satire exhibits the self as essentially divided against itself. One can see this most clearly at work in Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew, subtitled a satire, where the action consists of a dialogue between two characters, an ‘I’ and a ‘He’, incarnations of the two opposed sides of the same psyche, one governed by reason, the other by appetite. Diderot’s point is that we are, at the very least, two-faced beings: desiring creatures possessing a rationality that never succeeds in suppressing our appetites. Priggishness, censoriousness and the seemingly endless capacity for self-justified moral outrage flow from the denial of our Janus-faced nature. We find this taste for satirical self-division in Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous texts and Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. But nowhere is it more rabid than in the tragic-comic division of the self that one finds in Nietzsche’s very late ‘autobiography’,

77

Ecce Homo. Mocking Pilate’s words to the scourged Christ, it is clear from the title that we most certainly do not ‘behold the man’ – one, unified and unique – but a satirically split self whose chronic divisiveness is playfully accentuated through chapters titles like ‘Why I write such excellent books’, ‘Why I am so clever’ and ‘Why I am a destiny’. Satire is the comic expression of the division of the self. As Rimbaud said, Je est un autre. But why is it that one can only present one’s own ideas in the guise of another, or many others? Why is direct speech either impossible or simply dull? What is the necessity for linguistic indirection?

78

Being

Martin Heidegger’s 1927 book, Being and Time, is considered by some (including me) to be the most important and influential work of philosophy written in the 20th Century. Yet, as readers of this monumental and monumentally difficult book know to their cost, there is precious little discussion of the ostensive subject matter of the book – the meaning of being. Heidegger keeps nudging the question of being’s meaning into the future, postponing it until it falls over the edge of the published tome. Heidegger focuses rather on trying to define the meaning of the being of that being for whom being is an issue, as he puts it, namely the human being or Dasein. Yet, about five chapters into the First Division of the book, Heidegger momentarily pulls back and expands the focus of his concern. He writes,

79

If we are inquiring about the meaning of being, our investigation does not then become a “deep” one (tiefsinnig), nor does it puzzle out what stands behind being. It asks about being insofar as being enters into the intelligibility of Dasein. The meaning of being can never be contrasted with entities, or with being as the ‘ground’ (‘Grund’) which gives entities support; for a ‘ground’ becomes accessible only as meaning, even if it is itself the abyss of meaninglessness (Abgrund der Sinnlosigkeit). That is, meaning is not deep. It is not a question of looking behind what appears for some hidden meaning which structures appearance. Inquiry into the meaning of being is not deep either. It just sounds deep. It sounds like we are after a ground, something determinate but hidden, something behind the scenes that pulls the strings of the world’s stage. This is what we might call a metaphysical misconstrual of both the meaning of meaning and the possible meaning of the meaning of being. The problem with being-talk is that it sounds as if being has some fantastic agency of its own, or that it is ‘miraculously transcendent’ as Glaucon ironically replies to Socrates as he is about to introduce the

80

three similes for the relation of the soul to the Good at the enigmatic center of the Republic. One can easily be persuaded of the mistaken idea that being is pulling the strings behind the scenes, like some sort of puppet-master and doing amazing things like shaping human action in the world and producing various historical epochs. This is an error. Worse still, it succumbs to the sort of obscurantist temptation that continually seduces readings and readers of Heidegger. Too many readers of Heidegger see being as some kind of rabbit in a hat. There is no rabbit. The point is to learn see the hat without wanting the rabbit.

81

Possibly dolorous tropical lyrical coda

As night falls in the mountains, the sounds of birds and the buzzing of insects slip away to near silence, as the first frogs are heard and their huge broad bass begins to spread across the valley floor. Then, from nowhere in particular, growing like a great slow swell in the ocean, the crickets add their pulsating treble. The all-encompassing twilight vibrates with sound. I can no longer hear myself. I shut my eyes in the hammock and await the appearance of stars.

83

Univocal Publishing 123 North 3rd Street, #202 Minneapolis, MN 55401 univocalpublishing.com ISBN 9781937561499

![ABC of Nutrition (ABC Series) [4 ed.]

0727916645, 9780727916648](https://dokumen.pub/img/200x200/abc-of-nutrition-abc-series-4nbsped-0727916645-9780727916648.jpg)