A Social History of the Cloister: Daily Life in the Teaching Monasteries of the Old Regime 9780773569416

A Social History of the Cloister is a study of life in teaching convents across France through two hundred years of hist

171 91 46MB

English Pages 376 [1172] Year 2001

Polecaj historie

Citation preview

01_deb.fm Page i Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

A Social History of the Cloister

01_deb.fm Page ii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

m c gill-queen’s studies in the history of religion Volumes in this series have been supported by the Jackman Foundation of Toronto. series two In memory of George Rawlyk Donald Harman Akenson, Editor Marguerite Bourgeoys and Montreal, 1640–1665 Patricia Simpson Aspects of the Canadian Evangelical Experience Edited by G.A. Rawlyk Inifinity, Faith, and Time Christian Humanism and Renaissance Literature John Spencer Hill The Contribution of Presbyterianism to the Maritime Provinces of Canada Charles H.H. Scobie and G.A. Rawlyk, editors Labour, Love, and Prayer Female Piety in Ulster Religious Literature, 1850–1914 Andrea Ebel Brozyna Religion and Nationality in Western Ukraine The Greek Catholic Church and the Ruthenian National Movement in Galicia, 1867–1900 John-Paul Himka The Waning of the Green Catholics, the Irish, and Identity in Toronto, 1887–1922 Mark G. McGowan Good Citizens British Missionaries and Imperial States, 1870–1918 James G. Greenlee and Charles M. Johnston, editors The Theology of the Oral Torah Revealing the Justice of God Jacob Neusner

Gentle Eminence A Life of George Bernard Cardinal Flahiff P. Wallace Platt Culture, Religion, and Demographic Behaviour Catholics and Lutherans in Alsace, 1750–1870 Kevin McQuillan Between Damnation and Starvation Priests and Merchants in Newfoundland Politics, 1745–1855 John P. Greene Martin Luther, German Saviour German Evangelical Theological Factions and the Interpretation of Luther, 1917–1933 James M. Stayer Modernity and the Dilemma of North American Anglican Identities, 1880–1950 William Katerberg The Methodist Church on the Prairies, 1896–1914 George Emery Christian Attitudes Towards the State of Israel, 1948–2000 Paul Charles Merkley A Social History of the Cloister Daily Life in the Teaching Monasteries of the Old Regime Elizabeth Rapley

01_deb.fm Page iii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

series one G.A. Rawlyk, Editor 1 Small Differences Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants, 1815–1922 An International Perspective Donald Harman Akenson 2 Two Worlds The Protestant Culture of Nineteenth-Century Ontario William Westfall 3 An Evangelical Mind Nathanael Burwash and the Methodist Tradition in Canada, 1839–1918 Marguerite Van Die 4 The Dévotes Women and Church in Seventeenth-Century France Elizabeth Rapley 5 The Evangelical Century College and Creed in English Canada from the Great Revival to the Great Depression Michael Gauvreau 6 The German Peasants’ War and Anabaptist Community of Goods James M. Stayer 7 A World Mission Canadian Protestantism and the Quest for an New International Order, 1918–1939 Robert Wright 8 Serving the Present Age Revivalism, Progressivism, and the Methodist Tradition in Canada Phyllis D. Airhart 9 A Sensitive Independence Canadian Methodist Women Missionaries in Canada and the Orient, 1881–1925 Rosemary R. Gagan

10 God’s Peoples Covenant and Land in South Africa, Israel, and Ulster Donald Harman Akenson 11 Creed and Culture The Place of English-Speaking Catholics in Canadian Society, 1750–1930 Terrence Murphy and Gerald Stortz, editors 12 Piety and Nationalism Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Catholic Community in Toronto, 1850–1895 Brian P. Clarke 13 Amazing Grace Studies in Evangelicalism in Australia, Britain, Canada, and the United States George Rawlyk and Mark A. Noll, editors 14 Children of Peace W. John McIntyre 15 A Solitary Pillar Monreal’s Anglican Church and the Quiet Revolution John Marshall 16 Padres in No Man’s Land Canadian Chaplains and the Great War Duff Crerar 17 Christian Ethics and Political Economy in North America A Critical Analysis of U.S. and Canadian Approaches P. Travis Kroeker 18 Pilgrims in Lotus Land Conservative Protestantism in British Columbia, 1917–1981 Robert K. Burkinshaw

01_deb.fm Page iv Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

19 Through Sunshine and Shadow The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Evangelicalism, and Reform in Ontario, 1874–1930 Sharon Cook 20 Church, College, and Clergy A History of Theological Education at Knox College, Toronto, 1844– 1994 Brian J. Fraser 21 The Lord’s Dominion The History of Canadian Methodism Neil Semple 22 A Full-Orbed Christianity The Protestant Churches and Social Welfare in Canada, 1900–1940 Nancy Christie and Michael Gauvreau

23 Evangelism and Apostasy The Evolution and Impact of Evangelicals in Modern Mexico Kurt Bowen 24 The Chignecto Covenanters A Regional History of Reformed Presbyterianism in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, 1827 to 1905 Eldon Hay 25 Methodists and Women’s Education in Ontario, 1836–1925 Johanna M. Selles 26 Puritanism and Historical Controversy William Lamont

01_deb.fm Page v Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

A Social History of the Cloister Daily Life in the Teaching Monasteries of the Old Regime elizabeth rapley

McGill-Queen’s University Press Montreal & Kingston • London • Ithaca

01_deb.fm Page vi Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

© McGill-Queen’s University Press 2001 isbn 0-7735-2222-0 Legal deposit third quarter 2001 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec Printed in Canada on acid-free paper This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. McGill-Queen’s University Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (bpidp) for its activities. It also acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for its publishing program.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Rapley, Elizabeth A social history of the cloister: daily life in the teaching monasteries of the Old Regime (McGill-Queen’s studies in the history of religion) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-7735-2222-0 1. Monasticism and religious orders for women – France – History. I. Title. II. Series. lc506.f8r36 2001 271′.903044 c2001900081-2

This book was typeset by Dynagram Inc. in 10/12 Baskerville.

01_deb.fm Page vii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

Contents

Acknowledgments Illustrations

ix

xi

Introduction

3

part one

two hundred years

1 The Nuns and Their World

13

2 For Richer, for Poorer: The Monastic System and the Economy 29 3 The Dilemmas of Obedience

49

4 “Personae non gratae”: Jansenist Nuns in the Wake of Unigenitus 64 5 The Decline of the Monasteries 6 Aftermath part two

78

96 t h e a n at o m y o f t h e c l o i s t e r

7 Clausura and Community

111

8 The Three Pillars of Monasticism: Poverty, Chastity, Obedience 130 9 Prehistories

148

01_deb.fm Page viii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

viii

Contents

10 Novices

164

11 “The Servants of the Brides of Christ”

182

12 Of Death and Dying 198 13 The Institut

219

14 The Pensionnat Conclusion

234

257

Appendix: Demographics of the Cloister 261 Glossary Notes

285

289

Bibliography

349

Index 371 A map of the three teaching congregations appears on page

275

01_deb.fm Page ix Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank her husband, who has encouraged her and researched with her during all the years that she has worked on this book. Most particularly, she thanks him for the many patient hours he has spent bringing order and meaning to her data. She acknowledges the assistance given to her by a number of people in France, notably Chanoine Michel Veissière, Madame Marie-Thérèse Notter, Cécile Amalric, odn, and the municipal librarians in Montargis and Provins. She thanks the editor of the Proceedings of the Western Society for French History for agreeing to the inclusion in the book of material previously published in that journal. Finally, she would like to express her lifelong gratitude to Beatrice Binney, rscj, a wonderful history teacher, to whose memory she dedicates this work.

01_deb.fm Page x Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

01_deb.fm Page xi Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

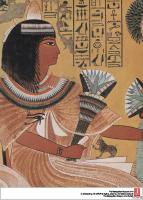

P. Helyot, Dictionnaire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires (Paris: N. Gosselin, 1714–1719),vol. 6, opposite p. 355. Courtesy of University of Ottawa, Rare Books Collection.

01_deb.fm Page xii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

xii

Contents

Vol. 2, opposite p. 425.

01_deb.fm Page xiii Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

xiii

Folio

Vol. 4, opposite p. 185.

01_deb.fm Page xiv Tuesday, July 24, 2001 1:27 PM

xiv Contents

Vol. 4, opposite p. 166.

L21644.bk Page 1 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

A Social History of The Cloister

The persons whose virtues are proposed for our meditation are not strong men who have crossed the seas to take the Gospel to the infidels; they are simple women like ourselves, whom we have seen sanctifying themselves in our midst, in the practice of the same Rules, in fidelity to the same usages. “Annales des Ursulines de Blois,” 1714

L21644.bk Page 2 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

L21644.bk Page 3 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

Introduction

I think I must start by saying that during the years the nuns in my study were bending themselves to their mission of recatholicizing the world, my own ancestors, both English and Scots, were all dyed-in-thewool Protestants, who probably never saw a papist in their lives. My English ancestors lived in Huntingdonshire, one of the most Puritan of counties, and their allegiance was to Oliver Cromwell. Even during my mother’s childhood in the early years of the twentieth century, no family member was allowed to criticize the great man. A sort of residual loyalty, then, gives me my excuse for starting with a story about Cromwell. Having risen to power, he needed to do the right thing and pose for a portrait. But while the portrait was necessary, the flattery that customarily went into it was not. In that respect, Cromwell was not like most other great men. His words to the artist have lived on, even though most of his other words have faded: “Mr Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.”1 Far be it from me to compare French nuns in their convents to a soldier-statesman in Westminster – surely, both nuns and statesman would have been most insulted at the suggestion – but I think that perhaps they too would have appreciated a faithful portrait, warts and all. This would not have been their first choice, which would be no portrait at all; for they wished to live in obscurity. “The name of a religious ought to be as unknown and solitary as her person,” wrote one of them.2 Many of the more eminent among them took care to preserve

L21644.bk Page 4 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

4 Introduction

that obscurity by burning their papers before their death. But the problem is that obscurity has not been kind to them. If you do not see to your own history, someone else will see to it for you. In their case, the absence of evidence has been taken for irrelevance, and self-disparagement has turned into disparagement by others. A true portrayal, warts and all, is one thing, but a concentration on warts to the exclusion of all else is another. The nuns of the Old Regime were the subject of considerable hostile analysis by people who had never been inside their convents’ doors. They were accused of “idleness, childishness, back-biting, hypocrisy, sentimentality in prayer, prudery, preciousness, affectation and vanity.”3 Worse, they were suspected of harbouring “volcanic” passions, which were kept in check only by the locks on their doors and the bars on their windows. Their image did not improve with time. In the nineteenth century, when France was shaken by monumental church-state battles, religious women, loyal troops of the church as they were, caught the edge of the anticlericals’ hostility. The literature abounded in negative images; a nun was “the disappointed lover, the intriguer, the harridan, the person whom one designates … by the intentionally equivocal expression ‘good sister,’ and finally, the pseudo-mystic.”4 What had nuns done to deserve such harsh treatment? In answer to this question there was only silence. No one had entered the public domain to speak for the nuns. If they themselves had spoken, they would probably have said, “I will not dignify this with a response.” That is certainly how they acted. For the most part they swathed themselves in privacy. However warm and kind they may or may not have been among themselves, they treated “the world” with hauteur. They did not owe it an explanation, still less a justification. They cherished their apartness, cultivating the “us against them” mentality. Had they wished to persuade others of their value, they certainly had the means. Over the years they produced, or arranged to have produced, many biographies and historical monographs. But these works were designed strictly for home consumption, and their purpose was hagiographical. Their subjects were the institutions or the founders and other women who might qualify for canonization. Intended to edify, these writings seldom allowed even the mildest criticism, the slightest hint of humanity. Hagiographies, of course, preach only to the converted. This was the problem with this old convent literature. It had no intention of reaching across the great divide, to tell the world what it was really like to live in community under the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. So the reader was left with two extremes: the hostile and generally uninformed writings of the outsiders, and the carefully crafted and

L21644.bk Page 5 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

5 Introduction

sanitized tributes of the insiders. The consequence of this extremism was the loss of a sense of balance. Only recently have there been an increasing number of works that seek to portray religious women as they really must have been – warts and all, and far more connected to the human race than we have ever been allowed to believe. Another great problem with the insider literature is that it was fragmented. No one spoke for monasticism or even Catholicism as a whole. This is characteristic of older Catholic historiography. It has been pointed out that in the period when Reformation history was taking shape under the hands of great Protestant scholars, “Catholic historical scholarship, chartless and rudderless … hardly sought to synthesize but was content to record, piecemeal, reforms, resistances, counter-offensives.” As a result, for many years the movement known as the Counter-Reformation was defined by its opposition, and suffered accordingly.5 This failure of Catholic historiography must surely be blamed partly on the religious orders, whose allegiance seemed too often to belong to their own institutions rather than to the universal Church. The infighting to which they were so prone found permanent expression in their writings. In the older literature of any religious order you will find yourself within an intellectual cloister where the brothers are everything and the rest of the world is barely mentioned. Loyalty to the in-group was matched by indifference and sometimes even hostility towards the outsider. The history of monasticism and the religious orders was, for these earlier historians, the history of individual orders and societies. With religious women, this fragmentation was taken to extremes: from individual societies to individual houses. Look at the bibliography at the end of this book, and among the older works you will see a host of monographs, each dedicated to a single community. We can fit them together to form a sort of mosaic of female monasticism, but in doing so we are circumventing their original purpose. In keeping with the dictates of the Church and the prejudices of society, the female monasteries of France were cut off, not only from the world but from each other. The spirit of isolation was built into their communities at the time of foundation, and it endured through the years.6 From within the circle of their own walls, nuns tended to regard outsiders with caution, and other religious orders with outright coolness. A sense of apartness filled their minds, so they would have been most surprised to learn that they were really not as unusual as they thought. It was only in the later twentieth century that historians began to supply the syntheses that treat religious women as members of an identifiable countrywide group, sharing many of the same ideals, objectives, and problems.7

L21644.bk Page 6 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

6 Introduction

I have followed this path, drawing a large picture with material that was originally intended for small pictures. This has required some audacity, because the three congregations with which I am concerned – the Compagnie de Sainte-Ursule, the Compagnie de Marie NotreDame, and the Congrégation de Notre-Dame – are still very much alive and active, teaching children all over the world. They have every right to shake their heads at the liberties I have taken in grouping them together; after all, there were differences between them; they were not the close copies of each other that my broad-brush methodology may suggest. And even if similarities may be found in their rules, organization, and lifestyle, the geographical distribution of their communities always tended to intensify their differences. Each cloister had its own character at a time of great regional diversity in France. So is it legitimate to group together the large and prestigious monasteries of great cities with the small houses buried in towns of two or three thousand souls? Or to group the communities of bustling port cities with those of slumbering provincial backwaters? My only defence can be that while some particularities are lost, many perspectives are gained in the telling, and I hope that the latter will make up for the former. The other great problem has been the passage of time. The period covered in this book extends from the early seventeenth century to the late eighteenth – the period generally known as the Old Regime. In writing social history, it is tempting to treat blocks of time as though they were a unified whole. Yet during those two centuries French society did not remain static. At its different levels it progressed unevenly, some parts of it leaping ahead while others remained virtually immobile. The cloisters about which I write existed simultaneously on these different levels. They were (for the most part) urban and therefore were not immune to the forces at work in their cities; they were populated largely by daughters of the better off and better educated, and were therefore not entirely closed off from the winds of change. On the other hand, their way of life was inspired by the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, and their rules were designed to keep this way of life as intact as possible. “Edified and encouraged by the example of those who have gone before us,” the nuns of 1790 proclaimed, “we have no other ambition than to model our conduct on the exact discipline and constant regularity which they supported.”8 Was this unchangingness an illusion, or was it genuine? Were the sisters of 1790 really clones of the sisters of 1630? That was a question I asked over and over again as I researched this work. Time did make a difference. Monastery walls were not impervious to the currents that flowed through society at large. Had the cloister

L21644.bk Page 7 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

7 Introduction

existed in a vacuum, it might have remained unchanging. But events battered against its walls, creating circumstances to which the women inside simply had to respond. Whether they knew it or not, they did evolve – if only just enough to survive in a changing environment. Because the forces for change originated outside the walls, it is necessary to explain what was happening there. Part 1 is an introduction to the events which, over nearly two hundred years, dictated what happened to the women’s monasteries. Chapter 1 begins in the broadest terms, touching on the general topic of monasticism, both male and female, tracing the great fluctuations in its fortunes from the extraordinary period of growth in the earlier seventeenth century, through the dark days in the eighteenth century, and to the French Revolution. Chapter 2 turns to the three teaching communities with which we are concerned. They developed in the same context, enjoying the same rapid expansion before falling into the same drastically unstable economic environment of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Nothing before or after, until the Revolution, provided such a unifying experience for thousands of religious women as the misery they shared during these years. Chapter 3 falls back in time to consider the tensions inherent in the communities’ relationships with their bishops. One of the fictions about religious women is their supposed docility. “Their spirit, being sedentary, calm and patient, banishes the fear that they would ever wish to leave the circle which is traced for them by their duty and their Rule,” wrote a Crown minister at the time of the Restoration.9 This may have been true, both then and in the preceding centuries. But how did the nuns react when outsiders encroached on that circle of duty and Rule? On numerous occasions, the sensitivity of monastic communities to what they themselves called their “rights” led them into serious confrontations with the ecclesiastical authorities to whom they were subject. The degree to which they could be stubborn, combative, and downright disobedient was demonstrated in the eighteenth century in the regions of France that experienced the Jansenist crisis. Chapter 4 considers this crisis and its often tragic results. Chapter 5 takes up the themes of chapter 2. In the history of monasticism, the eighteenth century is remembered mainly for decadence and decline. Religious women have been associated in that decline, albeit with some reservations. This author joins with others in questioning that historiographical tradition. The female monastic population decreased, to be sure. But the convents were the victims not so much of moral decline as of an extremely adverse economy and an unsympathetic government. The Law Crash brought hundreds of communities to their knees. It is remarkable that so few of them actually

L21644.bk Page 8 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

8 Introduction

collapsed and that so many were still alive and in tolerable financial health at the time of the Revolution. Chapter 6, “Aftermath,” offers a brief glance at the women’s experience during the Revolution. While strictly speaking this experience belongs to another historical period, it is important to remember that it had its roots in an earlier time. The nuns who faced the guillotine, sat in the crowded prisons, or simply survived as best they could in rented rooms and garrets had been formed in the orderly and protected environment of the Old Regime cloister. Their negative reaction to the Revolution, unexpected at the time and mildly controversial to this day, was the fruit of that earlier life. Part 2 seeks to describe life within the cloister: the framework provided by the institutions, the spiritual and material problems of every day, the relationship of the women with one another, and their relationship to the world outside. Having paid due respect to time and space in part 1, I now sidestep their restrictions, drawing from sources scattered across the whole period and the whole country to create a composite picture of teaching nuns in the Old Regime. I am emboldened to make these generalizations by the knowledge that the very act of entering a convent and submitting to a Rule involved a certain loss of individuality. When all is said and done, there was much that was invariable about the cloister, whether in 1650 or 1750 and whether in Brittany or the Dauphiné, Burgundy or Poitou. In the early modern period, women’s horizons were limited, and religious women’s even more so. Once the parameters of their life had been set, few serious deviations were open to them. All monastic communities were built on the same foundations: the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and clausura (the obligation to remain within the cloister). To these obligations the three congregations in question added another: the holy apostolate of instruction, which they called their institut. The obligations imposed patterns on the lives of the women who undertook them. All their regional, cultural, and personal particularities and all the modifications caused by the passage of time had to fit within these patterns. At the same time, religious women always remained physically connected to the society around them. They shared in many of its customs and practices. They employed the same notaries, doctors, and legal advisers. They drank the same water and patronized the same butchers and grocers. They approached the problems of child rearing, nursed and medicated their sick, and attended their dying in much the same way as “the world” did. In fact, the records they kept about these things, at a time when women as a whole seldom wrote much about daily life, can provide useful information on life not only in the cloister

L21644.bk Page 9 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

9 Introduction

but also in the larger community that swirled around it only a stone wall away. Thus, this “social history of the cloister” is more than a cameo study of a small closed-off section of society; it has a bearing on the general history of women in early modern France. In a field of study where women’s self-expressions are difficult to find, it offers a wealth of material composed by women for women. Part 2 of the book is, for the most part, a collection of anecdotal evidence, drawn from the annales and other writings of religious women. In the appendix another perspective is offered: a look at the demographics of the population, extracted from the thousands of records of individual nuns that survive in various French archives, public and private. They provide sufficient evidence to reconstruct, at least in part, the life courses of the women: the age at which they entered religion, their staying power in the novitiate, and their age at death – and the effects on these life courses of time and geography. The records also reveal the changing shape of communities and the rise and decline in their populations, with all that this has to say about the evolution of the public’s opinion regarding the female monastic life. The importance of religious women in the world of the Old Regime should not be underestimated. As celibates in a society that counted on leaving many of its members celibate, as dutiful children in a system where family strategies were key to economic and social development, as devout practitioners of a faith and a moral code that sought to cover and permeate the whole land, as exponents of the state-building virtues of order and obedience, as pioneers in numerous fields of health care, and as the principal educators of thousands of growing girls – in all these roles, the religious women surely deserve to be recognized as full members of their society, especially its female part. As for the church of the Old Regime, if religious women do not loom large in its history, it is not so much for lack of evidence as for lack of interest. Few other groups have contributed so much to the life of an institution. It is the perception that others have had of their unimportance, added to their own obsession with privacy, that has kept them so long in the shadows. As I have said, this situation is now changing. Mine is only one of a number of studies that have been undertaken in the last decades, as a quick visit to my bibliography will show. I am sure that many more will follow; I certainly hope so. Other orders and congregations of nuns, both in France and in other countries, await their historians. Only when they too are documented will the religious women of the past have the history they deserve.

L21644.bk Page 10 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

L21644.bk Page 11 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

part one Two Hundred Years

L21644.bk Page 12 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

L21644.bk Page 13 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

1 The Nuns and Their World

Of the millions of women who have become Roman Catholic nuns over the last four centuries, a large proportion have been teachers. Most of these teaching nuns have belonged to religious orders that had their genesis in France. Who were the first professional nunteachers of France? Were they the little group of young women who joined together in 1592 in the Isle-sur-Sorgues, in the Comtat Venaissin, to live under the vow of chastity and to teach Christian doctrine?1 Or were they the five young women of Mattaincourt in Lorraine who, on Christmas Eve 1597, put black veils on their heads and announced that thenceforth they were going to live in community and teach school?2 Or – since none of these actually lived in the France of their day – was it yet another small group of women, established in Bordeaux and led by Jeanne de Lestonnac, baroness of Montferrand, who in 1607 received papal authorization “to offer to God a vow of perpetual chastity and to dedicate to Him their lifelong service in the formation of young girls in good morals and Christian virtues”?3 To borrow a phrase from Lucien Febvre, all this is “une question mal posée.”4 It matters little who was first across the starting line in this race to educate and Christianize, and thus save the female children of France. What is significant is the extraordinary power of the idea and the fact that, within a very few decades, it spread throughout the country. It has been described as a “contagion” and indeed it was, leaping from person to person and from town to town.5

L21644.bk Page 14 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

14

Two Hundred Years

If the contagion was to spread, it required certain conditions: young girls needing to be schooled, teachers to school them, and a heavy infusion of wealth to finance the whole complex of undertakings. None of these conditions could have been taken for granted in the circumstances of 1600. Girls had never before been thought to need schooling. One might well ask why they were thought to need it now. As a historian of primary education has remarked, it is astonishing that so many parents of the seventeenth century strove so hard to ensure that their children, both boys and girls, received instruction.6 There was little of the necessary infrastructure immediately available in the France of 1600 – the country, newly emerged from war, already had a great deal to do just to repair past damage. However, its distress at the devastation in its ancient Church, coupled with its alarm at the superiority of Huguenot teaching and preaching, provided the motive power. Thinking Catholics were convinced that heresy could only be combated by its own weapons – by better preaching and by building and staffing schools and colleges; and the postwar expansion in the agricultural sector that fuelled the economy provided them with the means to accomplish their new purpose.7 There remained the third necessary condition: teachers to do the work. Where girls were concerned these teachers had to be female, since both the Crown and the Church viewed any kind of coeducation with horror. Women had always taught school here and there, but never in great numbers. Now they crowded onto the scene, even before there were children to be taught or money to fund their efforts. The need that drove them was the need to do something about the desolate state of the Catholic faith – and, at the same time, to give vent to their own religious energy. Those early groups of women were inspired not so much by any pedagogical aspirations as by the desire, as one of them put it, “to do all the good that is possible.”8 And the good they sought to do was to be done from the base of a community life. Their decision to live in this way was as fundamental to their plans as was their apostolic purpose. The movement was highly dynamic. Its real growth spurt began after 1610. By the time this was over in 1670, the three small groups of 1592, 1597, and 1607 numbered among them close to five hundred communities – about a one-quarter of the total number of female monasteries of every kind that have been counted for the Old Regime. Virtually every substantial town possessed at least one convent of teaching nuns. The phenomenal growth of the teaching congregations was part of a wider sea change taking place in French female monasticism. The women’s monastery was not, of course, an invention of the Counter-

L21644.bk Page 15 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

15

The Nuns and Their World

Reformation; it was as old as France itself.9 But the passage of years and the ravages of the religious wars had taken their toll, so that by the beginning of the seventeenth century both the population of monastic women and their religious purpose were sadly attenuated. Whereas, at their apogee, the great abbeys – Benedictine, Cistercian, Fontevrist, and others – had housed hundreds of nuns, their numbers were now diminished and their purpose degraded. In the countryside around Paris, for example, seven abbeys and one priory existed in a state of vegetation, with populations of between twelve and sixteen nuns apiece, leading lives largely innocent of any monastic discipline.10 Within the cities, convents of mendicant nuns – Franciscan, Dominican, and others, some richer, some poorer – also struggled to survive. But the life they offered did not seem to meet the needs of contemporary women. As Jeanne de Lestonnac explained, they were either too physically demanding or too relaxed: [Of] the many women who would like to serve God in religion some are constrained, because of the austerity of the Rule and the weakness of their bodies, to remain in the world … Others, seeing that the primitive spirit of charity, devotion and perfection is almost extinguished in the ancient [monastic] families, and [that there is a] lack of spiritual aids therein, do not dare to join them … for fear of finding spiritual death where they looked for life.11

It was not from these ancient institutions that the great surge of religious activism arose. By the time such institutions managed to renew themselves, they were already almost submerged in the flood of new monastic creations. Port-Royal, Montmartre, and other famous houses might have had great influence and respect in French society, but the huge energy of the years of “Spiritual Conquest” came from newly established communities such as the Carmelites, the Visitation, and the three teaching congregations to whom this work is dedicated. The teaching congregations represented a new, hybrid form of religious life. In accordance with the custom at the time of their foundation, they were strictly enclosed,12 and they gave a good part of their day to prayer, spiritual reading, and meditation. Their originality lay in their apostolic intention, their institut* – the saving of souls through the instruction of children. They differed from the contemplative orders in that teaching rather than prayer was their principal objective. “The teaching function is the prime purpose of our institute, for the greater glory of God, for the salvation of souls and for the public good,” stated the Rule of the Compagnie de Notre-Dame;13 the other * Words marked with an asterisk are defined in the glossary.

L21644.bk Page 16 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

16

Two Hundred Years

two congregations held the same view. “The public good” was an idea to which they readily paid homage. Wherever they went, they drew up contracts with the city authorities whereby they undertook to teach, at no charge, all young girls who came to their door. As soon as they could, they opened their classrooms, and the children always came flooding in. If there is one fact that appears universally in their records, it is the instant popularity of their free schools. These schools became an integral part of the social structure, and they changed the way France felt about female education. The opening pages in the history of convent education are marked by intense enthusiasm and a supernormal degree of dedication. The movement was young, as were the women who joined it; it was given to all the extremes and excesses that accompany a religious revival – which, of course, is what it was. We shall see it grow older and wiser with the passage of time. But the point to remember is that many of the first generation of nuns were zealots, and as zealots they simultaneously aroused both admiration and alienation in the society around them.

th e c o nv e nt ua l i n vas i o n The movement of women into the religious life in the early seventeenth century was part of what has been called a “rush”,14 a levée en masse.15 Again, it has to be emphasized that the great change came from the mushroom growth of new religious congregations, both male and female. It was they who provided the muscle for what has been called “a fantastic conventual invasion.”16 Communities of every stripe and every purpose formed up and then, within a few years, spun off subcommunities and even sub-subcommunities. They became Catholicism’s front-line fighters in the battle to regain the advantage from the Huguenots. In this they were highly successful, and along with their proselytizing, they brought civility and learning to a people badly scarred by war. But in their very success lay a serious social problem. Each of these new communities had to find its own place in the sun: its funding, its circle of supporters, and its living quarters. The older orders were already well endowed with land and feudal revenues, the fruit of centuries of acquisition.17 The new orders had nothing until they could find new sources of wealth. The supply, however, was not equal to the demand. The wealth of the countryside depended on the labour of the peasantry, which – no matter how pushed – was finite. Naturally, the landowning families had their own ideas on how to use any surplus. When some of their more devout members began to divert large

L21644.bk Page 17 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

17

The Nuns and Their World

slices of the family fortune into religious institutions, serious internal divisions developed. These became more intense as the century progressed and as the provincial nobility began to suffer economic and social decline.18 The huge generosity which the gens de bien showed the monasteries at the outset did not last long. The local elites bestowed more than money on the religious congregations; they also gave them their children. “It was not unusual, in Paris and everywhere else, for the sons and daughters of good houses – men and women of quality – to go off and enter these orders,” wrote Pierre de l’Estoile in 1606.19 Many families followed up with support and affection for the same orders. But with the passage of years, as they became more straitened in their circumstances and more sceptical in their thinking, they began to withhold both money and children.20 This put the new religious communities at risk. Since their strength had come from their close identification with the upper classes, their decline began when the same upper classes lost interest. “The solidarity of noble and convent, so complete in the seventeenth century, carried within it problems for the future, when the descendants of the zealous reformers would become more indifferent towards the Church, and begin to oppose the diminishment of their patrimony in favour of the religious orders.” So writes the historian of religious orders in Brittany.21 What he says applied equally across the country. The last of the new communities’ requirements was perhaps the one that caused the most trouble: the need for space. Almost to a man (or woman), they looked for a place inside the cities. But these cities, in the early 1600s, were still cramped tightly within their defensive walls, with houses piled on each other across narrow alleyways, and public space always at a premium. The arrival of a new religious community meant the dislodgement of ordinary households. The establishment of seven, eight, or more new religious communities, complete with cloisters, gardens, cemeteries, and churches, meant in many cases the virtual takeover of the intra-muros. And more than space was involved. Church property enjoyed numerous tax exemptions. Thus, every private house that was absorbed into a monastic space meant a loss for a city’s tax base. So while some people were enthusiastically encouraging the establishment of new religious communities, others (including municipal officials, assemblies of citizens, and local parish clergy) actively opposed them.22 These people feared that whatever limitations on expansion the new communities initially agreed to, they would break the agreements once they were installed. “We all know that the communities settle for an inch of land when they arrive, and then afterwards spread out by degrees,” commented a critic.23 A truer word was never spoken.

L21644.bk Page 18 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

18

Two Hundred Years

The conventual invasion was rather like a gold rush in that literally hundreds of communities, male and female, appeared at the gates of scores of cities, anxious to stake their claims. At issue was the wealth, patronage, and support of the elites of those cities. The first to come were usually the first served. Others were closed out or had to settle for less affluent locations with less promising prospects – in the faubourgs or in smaller towns. Given the overcrowding of the course, it is easy to see why the competition was so fierce. This brings up a dark side of the conventual invasion – the rough way in which the congregations treated one another in their haste to secure for themselves the best places in the best cities. They slandered each other without hesitation and used all their influence to keep others off what they considered to be their territory. The Jesuits came to have a bad name for their use of defamation and dirty tricks, but in fact the other orders did the same. Cistercian monks, jealous of the influence which the Capuchins were beginning to exercise over PortRoyal, labelled them “sneaks, sanctimonious hypocrites and zealots,” according to Angélique Arnauld.24 The Cordeliers battled against the Capuchins in one town; they kept the Récollets out of another, preaching that they were parasites who took bread from the mouths of the poor.25 The Minims succeeded in persuading the commune of Abbéville to keep a group of nuns out of the city.26 The mendicants of Lille petitioned the authorities to get rid of the Ursulines whose schools, they claimed, were teaching vanity rather than piety.27 The examples could go on and on, some of them involving fisticuffs.28 Even in an age known for its quarrelsomeness, this infighting was damaging to the image of the orders and was grist to the mill of the ever-present anticlericals: “These ambitious men,” wrote one of them, “when they get the ear of powerful people at court or among the Robe, never fail to speak ill of the others, so as to make them despised, and to build themselves up on their ruins.”29 Thus, the religious rebirth of the seventeenth century, though impressive in so many ways, had its negative side. Catholic France made space for the new orders, but it did not wholeheartedly embrace them. As the years passed, its fears about them were confirmed: the economic base of the cities did indeed begin to dwindle away. “It is certain that the [religious] communities, very numerous, occupy the greater part of the city’s terrain,” wrote a royal engineer in Laon in 1701. “The said communities, founded more than a century ago, [have ruined] more than 150 houses, uniting entire streets to their monasteries, so that the number of inhabitants, the only contributors to the expenses of the city, is notably diminished.”30 It was a grievance that could not be redressed and was never forgotten. The superabundance of regular

L21644.bk Page 19 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

19

The Nuns and Their World

clergy contributed greatly to their unpopularity – and, some have said, to their eventual decadence.31

the first confrontations The naysayers had always been there, but in the first exuberant years they may have sounded like frogs croaking in the marsh. With time, however, their chorus began to swell. At the mid-seventeenth century, disenchantment was turned into action. The first sign that the times were changing came from the Crown itself, and it was over the question of money. The difficulty lay in the Church’s tax exemption. According to ageold custom, ecclesiastical property, whether land or buildings, was considered to be the portion given to God and the service of the poor, and on this account to be withdrawn forever from general circulation. It was held “in mortmain.” In this condition it escaped the taille, the Crown’s main tax, and various feudal dues. At the beginning of the Bourbon regime, huge holdings across France – as much as 10 percent of the country’s landed wealth – were already off limits to the royal fisc. The acquisitions of the new religious congregations only enlarged this pool of untaxable wealth. However, the Crown had its own ways of compensating for its losses. To make up for the revenues that it would henceforth forfeit, it was entitled to collect, at the time of purchase, a fixed percentage of the sale price. This was known as the due of amortissement. If paid at the time of purchase, it was not too hard on the purchaser, but the Crown often overlooked the dues until such time as it was in financial straits; it then demanded the arrears in a single payment. This is what happened around the middle of the century. Under the regency of Marie de Médicis and through the earlier part of Louis XIII’s reign, the Crown had been indulgent to the new religious communities. Because they had been founded recently, they had no inherited property, so it was only natural that as soon as possible they would go on a buying spree, acquiring not only their conventual buildings but also investment property, both urban and rural. Legally, all this property was subject to dues of amortissement. But in the climate of benevolence then prevailing, the fees were either waived or – more often – simply ignored. In 1638, however, as the government’s need for money grew more pressing, the king’s first minister, Cardinal Richelieu, turned his eyes in this direction, claiming that the Crown had the right to the payment of dues of amortissement, with or without the consent of the Clergy. He faced stiff resistance from most churchmen, who were exceedingly

L21644.bk Page 20 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

20

Two Hundred Years

jealous of their privileges. A confrontation followed, which was settled only when the Clergy offered the Crown a “free gift” of 5,500,000 livres, and the Crown agreed to forgive all dues then owing.32 It was the Clergy’s hope that it might, now and forever, escape paying directly to the Treasury. However, the Crown did not surrender the right to tax religious corporations at will. “The law of amortissement is just, because the State renders it necessary,” the Crown argued. The king was free to levy taxes or not, at his pleasure.33 It was only a matter of time before the government would return to the attack. Meanwhile, with the passing years, the Clergy was losing popular support. Its tax privileges, so fiercely defended, cost it dear in the eyes of the public. Furthermore, the proliferation of monks and nuns, at a time when the economy was under stress, seemed to more critical minds to be tantamount to the creation of a new class of expensive idlers – “much like fleshy excrescences, which drain nourishment from a body of which they are an integral part.”34 It was also said that such people, by their celibacy, were depriving the state of much-needed future citizens. These populationist theories lent weight to the outand-out resentment that many felt towards the monasteries, over what was perceived as their unfair share of the country’s wealth. These views found expression through Louis XIV’s omnicompetent minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who came to power determined to cut down to size the various institutions which he considered a burden on the economy. As early as 1664, he was looking for ways to diminish the number of “monks of both sexes, who only produce useless people in this world and, often enough, devils in the next.”35 Colbert consulted with several councillors of state and in 1666, when the answers he received confirmed his own opinions, published an edict ordering a countrywide investigation into religious houses, with the intention of reducing their numbers where possible. Communities were visited by commissioners of the Crown and were required to show their letterspatent of authorization and their statements of accounts. Those that could not justify their existence were forced to close. The minister would have gone further, by raising the minimum age of entry to twenty-five for men and twenty for women, and by placing a limit on the value of religious dowries – and also, significantly, on the value of marriage dowries, which, in Colbert’s opinion, were becoming so high that they were forcing parents to put some of their daughters into convents. But in this he was ahead of his time, and he had to abandon the project. Even with all the resources of the Crown at his disposal, Colbert could not overcome the resistance of the Clergy. However, the line of thought he was following remained fixed in the minds of certain influential people. “There are too many monks,”

L21644.bk Page 21 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

21

The Nuns and Their World

claimed a pamphlet in 1669. “It is an abuse that prejudices the realm … and it is time to deal with it seriously and powerfully. Monks live in celibacy and make neither families nor children … Furthermore, the blind dependence by which they are attached to the wishes of the Pope forms an alien monarchy within the heart of France; and they draw the credulous to it, which is a matter of extreme consequence.”36 The respect with which the French elites had once viewed the monasteries was changing to irritation, even hostility; and the twin issues of money and power were, more than anything else, responsible.

the beginnings of decline If the clergy could not yet be brought to heel, they could at least be taxed. Colbert made the effort in 1674; he was blocked in the usual fashion, by another “free gift” of 520,000 livres. But time and the ineluctable logic of the Crown’s wartime financial needs brought the government to the attack once more in 1689. This time it had its way. The royal declaration of 1689 demanded payment of dues of amortissement on all investment property acquired by the gens de mainmorte since 1641.37 The clergy, no longer able to shelter behind a “free gift,” saw themselves subjected to out-and-out impositions. The Crown reaped a fine reward: 18,000,000 livres, as much as Richelieu had secured in twenty years of effort.38 The Crown’s gain was, of course, the clergy’s loss. Try as it could, the Assembly of the Clergy could not fend off the collection of the dues of amortissement. The tax was justified by custom and by law; what made it oppressive was its size and suddenness. If the dues had been paid regularly when property was purchased, they would have been manageable. But now, communities and corporations were required to pay out, in arrears, lump sums that could easily dwarf their total annual incomes. The result was, in the words of a contemporary publication, “a veritable Saint-Bartholomew for the clergy.”39 Since the Crown’s problems were far from over, the financial carnage (to continue the metaphor) was extended, with the invention of other taxes and the forced sale of offices, in the clerical as in the lay sphere. On average, the Clergy was now paying the Crown 6,400,000 livres per year, where in the period 1660–90 it had been paying 1,230,000.40 It still clung to its privileges by calling these tax payments “free gifts.” But one way or another, the king got his money. This all has to be placed in the context of massive overtaxation right across French society. Even with these increases in its burden, the Clergy was paying only a small fraction – about 3 percent – of the country’s annual taxes.41 The Church as a whole remained rich and its

L21644.bk Page 22 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

22

Two Hundred Years

credit solid. However, its weaker members were seriously affected by the new tax regime.42 Many individuals and communities – especially new communities and especially female ones – found that they were paying more than they could afford. Their carefully tended economies began to fall apart. “In the year that the taxes commenced, commenced also our decadence,” wrote one monastic annalist.43 Surviving financial records of Old Regime monasteries bear her out: 1689 was a watershed year, ending an era of expansion and beginning an era of decline. Taxes do not tell the whole story. The communities, struggling to make ends meet, found that much of their capital, which was placed out in loans, was now forever out of reach. The economic depression that dogged the last years of Louis XIV’s reign, combined with the continuing war and the government’s desperate attempts to raise more revenue, impoverished the whole society. The agricultural crisis, which brought the poor to starvation, also brought many once-prosperous people to bankruptcy. Those who had lent money to these people now found much of their money uncollectable. At the same time, the cost of living rose and the income from land dropped precipitously. Peace brought no relief. Indeed, as one observer remarked, “Those who have had the misfortune to have all their wealth in [financial investments] have already, in the space of six months of peace, faced more damage to their fortune and experienced more hardship than they suffered during twenty years of war.”44 The last years of Louis XIV’s reign were marked by severe instability in the money market. Then, in 1720, came what was to be the final disaster for the rentier class. France went into a giddy spiral of inflation, then collapsed into bankruptcy. This all resulted from the efforts made by John Law, with the regent’s full backing, to re-invigorate the country’s finances and refloat its economy. Law argued that the shortage of specie, which had depressed the country for years, could be corrected by creating a larger money supply through the issue of paper money. Part of the scheme involved forcing the rentier class, which for so many years had locked up a good part of the country’s wealth, to cough up its treasure and in return to receive shares in a new company, the Mississippi Company, and billets de banque. Thus, money that had been sterile would be put to work, and France would claim its rightful part of the rich returns that were pouring into other countries (mainly Britain and Holland). The country, Law predicted, would be lifted off the rocks by a buoyant tide of capital. But the scheme, which had much to commend it, was too ambitious for the society onto which it was foisted. Throughout the summer, inflation ran out of control; fortunes were made and lost with dizzying

L21644.bk Page 23 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

23

The Nuns and Their World

speed. In December came the crash. The billets de banque were declared to be worth little more than the paper they were printed on. The collapse in the value of money was particularly hard on the country’s lenders.45 Both public bodies and private debtors took advantage of the situation to pay off their debts in devalued paper money or to demand a reduction in the interest on their loans. All too often, threatened with bankruptcy themselves, they refused to pay up at all. In other words, as borrowers benefited from the bankruptcy, lenders suffered. Foremost among these lenders were religious corporations and communities. As one observer wrote, “Hospitals, parish vestries, secular and regular communities, above all those of women, and many other people who had no wealth other than their rentes, have been reduced to indigence.”46 This was no exaggeration. Many communities found their revenues reduced by as much as one-third or one-half.47 Recovery from the bankruptcy was, of course, a slow and painful process. Even societies as prestigious as the Jesuits had to conserve and save and scrimp. Women’s monasteries were particularly handicapped by their lack of flexibility. Tied down by their clausura and hampered by the sheer number of mouths they had to feed, they had few ways to help themselves. Their only option was to appeal for government assistance. And this threw them into a new jeopardy, because it made them dependent on an outside and none too friendly force. Starting in the mid-1720s, religious communities across the country began bombarding Versailles with appeals for help. The more audacious suggested that since the Crown had precipitated the crisis, the Crown ought to solve it. But the Crown’s first response was to turn the tables: to accuse the communities of improvidence, of extravagant building programs, of poor management of their property, and of accepting more women, for the sake of their dowries, than they could afford. “It is this excessive number, out of proportion to the monastery’s revenues, that has caused the failure of a great number of women’s communities,” wrote one jurist.48 After some reflection, it was also decided that the problem was systemic. There were too many convents for the good of the country, and it was “absolutely necessary to suppress an infinity of houses.”49 A commission was established by royal decree in 1727 to hand out assistance to communities in need. This “Commission des secours” was assigned a fund, out of which, in the first five years alone, it paid pensions to 558 houses.50 But it was also instructed to reduce “the excessive number of female communities with which the kingdom is burdened.” Poverty had laid the women’s monasteries bare to the censorious gaze of an officialdom, which had never liked them much and now found its opportunity to do something about them. Colbert’s chickens had come home to roost sixty years late.

L21644.bk Page 24 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

24

Two Hundred Years

The Commission des secours has been overshadowed by its successor, the Commission des réguliers,* to the point where, in many church histories, it is not even mentioned. Indeed, until 1969,51 it never received any serious attention. But it was in fact a major experiment in social engineering and a significant intrusion by the Crown into the business of the Gallican Church.52 Before it closed its doors in 1788, it had mandated the suppression of some 244 female monasteries and the reduction in size of many more. If this achievement fell far short of its initial ambition, it was only for lack of resources and the declining interest of the Crown.53 However, it had fulfilled its purpose. Between 1720 and 1789 the population of nuns in France was reduced by about one-third.54 It was altered, too, in other subtle ways. The reduction had been achieved not by throwing nuns out but by banning entries, thus limiting the intake of young subjects. As a result, female communities found themselves growing older as they grew smaller.55 They found themselves, as well, subjected to a much stricter tutelage than they had hitherto known – for the ostensible reason that they were becoming too independent.56 From now on, if they offended their bishops, tried to act independently, or showed signs of heterodoxy (in effect, Jansenism), the ban on the reception of novices could be continued indefinitely and pensions could be witheld. This fitted well with the prevailing passion for order. “For their own good,” wrote an adviser to the commission, “they need a greater subjection. They ought to be kept under a very close eye, by a power near enough to them to oversee their conduct.”57 The activity of the Commission des secours reached its peak in the years leading up to 1751. In other words, the reconfiguration of the female monastic world – a world that had been shaped during the Catholic Reformation – took place in an atmosphere already steeped in Enlightenment thinking. Not that the women themselves were penetrated by Enlightenment principles – they seem to have been more or less impervious to them – but the men who decided their future, whether laymen or prelates, were decidedly so. “Women’s convents,” they maintained, “ought to subsist only insofar as they are useful to the State, through the edification of prayer, through the instruction and education of children, through the care of the sick and the poor.”58 Utility remained one of their principal criteria. As for the bishops who were called upon to collaborate in the initiatives of the commission, their responses are revealing. Most of the serious opposition to the reengineering came from men with Jansenist leanings. This is not surprising; they had already forfeited the Crown’s good will because of their independence and so had little to lose from speaking their minds. The

L21644.bk Page 25 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

25

The Nuns and Their World

more worldly bishops, those with ambitions, concurred willingly with the commission’s initiatives.59 But we cannot dismiss them as mere sycophants. The free hand they enjoyed for many years suggests that their thinking reflected that of their own elite milieu. The spirit that had built the monasteries in the first place was now buried in the past.

monasticism, the “unloved” institution From mid-century onwards, the prevailing mood was hostile to monasticism. “At present it is fashionable to slander monks,” wrote a learned Benedictine monk in 1783.60 The chief reasons for this hostility were their perceived idleness and excessive wealth. And indeed the records show truly scandalous divides between the “haves” and “have-nots” of the ecclesiastical world. Canons and monks might enjoy revenues in the tens of thousands of livres at a time when parish churches were crumbling and salaried curés earned only 300 livres.61 “This handful of monks … possesses more wealth than all the curés of Cambrai, to the number of 700,” wrote the priests of that diocese, referring to the monks of a local monastery. They went on to berate the monks for their idleness: “We spend night and day in the rain going about the countryside to administer the sacraments, but these gentlemen would refuse to take four steps away from their home without a good carriage or at least a horse to carry them and a well-equipped valet to serve them.”62 The reason for this serious imbalance was the diversion, over a long stretch of time, of the wealth of the Church into the pockets of the rich and powerful. The diversion had proceeded in two stages. First, the tithe, which should properly have been applied directly to the support of worship and the care of the poor, was largely reserved for the gros décimateurs* – rich, old monasteries for the most part. Their only responsibility was to ensure the provision of religious services, which they could do by hiring priests at economical rates. The difference between intake and output was theirs to enjoy, while often the priests had to supplement their income by charging fees for services. In the second stage of diversion, the wealth of the monasteries themselves was shared out between the monks (or nuns) and their so-called abbots or abbesses – men and women appointed by the Crown, who often had only a pro forma connection to their abbeys but were entitled to a part of their revenues. This was known as commende, and it was an important part of the royal patronage system. If the king benefited from his power to bestow or withold such significant riches, the nobility benefited even more; it “confiscated for its own profit a large part

L21644.bk Page 26 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

26

Two Hundred Years

of the revenues of the Church.”63 The public anger which this aroused was expressed in no uncertain terms in the cahiers de doléances* of 1788. How did this affect the great majority of religious women in France, who were anything but rich? They seem to have suffered from guilt by association. They were not accused of excessive wealth or evil living, but they were dismissed as irrelevant, petty, and superstitious. Their monasteries were seen as gothic prisons, and they as poor silly victims. Their methods of hospital care came under fire from philosophes and physiocrats whose prime target was the hospital system itself. Their schooling, which had drawn so many people to them in the early decades of the seventeenth century, was pronounced outmoded. Many upper-class girls whose predecessors had grown up in monastic pensionnats were now tutored at home, where piety mattered less than social graces. As for the religious life itself, elite opinion was now strongly against it. “The convents have been judged and condemned,” wrote Louis-Sébastien Mercier. “Excessive inquisitiveness, bigotry and hypocrisy, monastic nonsense and claustral prudishness reign there. These deplorable monuments of an ancient superstition exist in the middle of a city where Philosophy has spread its light.”64 He would have argued, as others did, that the fact that women could still be found in them was simply proof that parental cruelty existed even in the Age of Enlightenment. It was time to open up these prisons and release the victims who languished within. It is no wonder, then, that the men of the Revolution were decided, from the very start, to do exactly that. In October 1789 they took action. Monasteries across the country were ordered to receive no more candidates to profession until further notice.65 The following February, all monastic vows were abolished. The religious orders were put on notice. In one way or another, the same message was delivered: “Liberty, or rather, life [will be] restored to the mass of victims of both sexes whom the self-interest of families, personal obligation or a passing fervour have cast into the horrors of the cloister and loaded with insupportable chains.”66 Throughout the spring and into the summer of 1790, commissioners went to every religious community in the country, offering the members freedom while at the same time making an inventory of their property. For monks, the options were stark: freedom with a pension or a continuation of religious life in changed circumstances, regrouped with strangers in houses other than their own. For nuns, there was a concession: they would be allowed to stay in their own houses, even though these now passed into state ownership. But they were encouraged to leave. This inquest was the closing ceremony in the history of religious communities in the Old Regime. In 1790, when it was launched, the

L21644.bk Page 27 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

27

The Nuns and Their World

king was still king, and the Church had not yet been reduced to a department of the nation. The nuns appeared in the records for the last time as communities, coming before the commissioners in solemn order, the superior first, the senior nuns next, the juniors bringing up the rear, their names in religion and their dates of profession all registered – as though all this was still important. Their responses to the inquiries of 1790–91 can be taken as a referendum on female religious life as viewed by those who lived it in the last years of the Old Regime. Whatever the reason (and various explanations have been offered), the overwhelming majority did not wish to leave it. From then until September 1792 those nuns who had opted to remain in community lived in limbo: still enclosed in their cloisters even though their vows were no longer legally valid; unable, as often as not, to receive the sacraments from their own priests; surrounded by familiar property and goods that were no longer theirs; and forbidden to receive pensionnaires or teach school, or even bury their dead in the cemeteries that lay within their walls. Some communities showed spirit, defying the constitutional church in every way they could. Others lay low and waited for better times. It made no difference what they did. In late September and early October 1792 they were all evicted. From then on, if the nuns appear in official records at all, it is as solitary individuals, ci-devant religieuses – prisoners on their way to punishment or small entrepreneurs eking out an existence in private teaching or in the production of goods; or petitioners, aging and impoverished, pleading for their pensions. The year 1792 drew a line under their history. Between the death of the monasteries that year and their revitalization in the nineteenth century lay an empty space of a decade and more. Although some nuns eventually returned to religious life, it was to new communities and new surroundings in a new age. This has been a broad-brush outline of the history of religious orders in France under the Bourbon monarchy, from the early 1600s to 1792. The conventual invasion of the seventeenth century was an extraordinary phenomenon, a huge display of human energy. It achieved its aim – the recatholicizing of French society. But the achievement was not without cost. The very size of the movement laid it open to charges of being overbearing and counterproductive. For all its spiritual vigour, the Catholic Reformation had its negative side. In material terms, the conventual invasion led to a reconfiguration of the urban landscape, with the apparatus of reformed Catholicism – the convents, colleges, churches, schools, and hospitals – absorbing more and more of the available space. Financially, it occasioned a drain

L21644.bk Page 28 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:41 PM

28

Two Hundred Years

on the country’s wealth, during the very years when the state was seeking to corner more and more of the wealth for itself. The very part of society upon which the religious orders depended for support – the elites – came to see this as an imposition which the country could ill afford. As the general economic climate worsened, the situation of religious communities became precarious. The more vulnerable of them, the female communities, were the first to fall. Stricken by the Law Crash of 1720, they were forced to throw themselves on the charity of the government – a dangerous move, as it turned out, since the government had already decided that there were too many of them. For the religious women of France, the 1720s and 1730s were the bleakest of times as they faced both impoverishment and the mandated reduction in their numbers. Eventually they achieved a financial recovery of sorts, but the damage to their public image was less easily mended. In the mind of the Enlightenment, monasticism, including female monasticism, simply had no raison d’être. The teaching communities were not immune to these changing circumstances. When the conventual invasion began they were there, instructing and proselytizing – and also accumulating property and wealth, thus making friends and enemies at the same time. They shared in the depression of Louis XIV’s later years and in the bankruptcy of 1720. And in the aftermath, as the antimonastic spirit of the prerevolutionary years billowed up, they were caught within it. All these events helped to shape their life within the convent walls. The following chapter will go into the records of these communities to examine the way in which they gained their fortunes and then lost them during their first century of existence (1620–1720). It will, I hope, serve to illustrate how closely the cloistered life was dependent on material conditions. Throughout the rest of the book this dependency should not be forgotten. It formed the foundation on which religious women built their social and spiritual life.

L21644.bk Page 29 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:47 PM

2 For Richer, for Poorer: The Monastic System and the Economy

t h e w ay s a n d m e a n s o f a c q u i s i t i o n There are two ways of looking at the crucial decades 1620–40, which saw the foundation of most of the teaching communities. One of them is the view from inside: the stories of the heroism of the anciennes mères and their battle against poverty and the inhumanity of man. Stories like that of the little community of Mâcon passing its first winter in a halfruined house, where “the wind came in from every side … and they had at night to hang their robes up to block the windows”; where the rain and snow leaked through the chapel ceiling; where the best they could afford was a pathetic little altar decorated with coloured paper; and where the senior nuns had to post guard at night over the gap in the wall that threatened their enclosure1 … Or stories of the six young women of the Congrégation, refugees from the war in Lorraine, who struggled to set up a community and a school in far-off Châtellerault, working long hours in their school “and eating dinner while warming themselves and diverting themselves a little … not being able to keep a regular order because they had so much work, work that was a joy for them, so great was their fervour”2 … Or stories of the first Ursulines of Blois living on a starvation diet and taking turns to warm themselves at their one small fire; rising early “to do the laundry, bake, chop and stack the wood, and carry in all the water, even for the wash”3 … And of the five young nuns of the Congrégation in Reims, who for several months slept on straw pallets and drank out of a single, shared earthenware pot, all the while facing down the city council, “who were well and

L21644.bk Page 30 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:47 PM

30

Two Hundred Years

truly angry, and seldom left us in peace … wishing to force us to leave, and threatening to tear down our grille.”4 Such stories took on the quality of legends, to be repeated by succeeding generations of nuns and shared with their many friends, supporters, and students. The other view of this period is the one from outside, held by people who saw the new congregations as invaders threatening the delicate balance of their cities. The communities were aggressive and tenacious, all for the sake of their sacred cause. They were accused of taking advantage of friendship wherever they found it, of knowing how to manipulate the networks of patronage, and of using their own self-sacrifice to soften or shame the hardest hearts. We see all these accusations in a memorandum drawn up in 1694 by Edmé Leveil, curé of Saint-Valérien in the city of Châteaudun: In the time of the most illustrious … bishop of Chartres, Jacques Lescot, the religious of the Congrégation … came from Lorraine to establish in the parish of Saint-Valérien … They were 3 or 4 from the city of Nancy who began this establishment … They begged M. Coffinier, canon of the château, and myself to take up a collection through the town for them.

The proceeds from this collection provided the nuns with enough to live on while they pursued a longer strategy: “They laid siege to Messire Jacques de la Ferté, dean of Saint-André, through the intermediary of one Barbier, his attendant,” asserted Leveil, and by their flattery persuaded the dean to give them his niece, with a considerable dowry – “upon which they forgot their country and resolved to stay in this city.” Later, they again “mounted a powerful barrage,” this time on another notable who had come into money. After receiving liberal gifts from him, said Leveil, they just as quickly forgot him and looked for patrons elsewhere: I write this to inform posterity of the humble beginnings of these religious and the disrespect that they have shown for those who rendered them all the services that piety could expect of them … Through the exercise of a deplorable poverty deserving of compassion and assistance, in no time at all they will be in a position to concede nothing to the “poor” order of Saint Benedict which has around 300 millions in revenue every year; what is more, this monastery will never be at peace, donec totum impleat orbem.5

This is bitter language coming from a parish priest. It should not be forgotten that the parish clergy were often hostile witnesses because of the inroads that religious communities made into their congregations. But it rings true: the religious of the Counter-Reformation were zealots,

L21644.bk Page 31 Monday, July 23, 2001 1:47 PM

31

For Richer, for Poorer